Debbie

Miller

Teaching Comprehension

in the Primary Grades

Reading

with

Meaning

Foreword by

Ellin Oliver Keene

Stenhouse Publishers

Portland, Maine

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Stenhouse Publishers

www.stenhouse.com

Copyright © 2002 by Debbie Miller

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any

form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information

storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders and students for permission to

reproduce borrowed material. We regret any oversights that may have occurred and will be

pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints of the work.

Credits

Pages 83, 113, and 114: “Ducks on a Winter Night,” “Dressing Like a Snake,” and “Song

of the Dolphin” from Creatures of Earth, Sea, and Sky by Georgia Heard. Copyright ©

1992 by Georgia Heard. Published by Wordsong/Boyds Mills Press, Inc. Reprinted by per-

mission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miller, Debbie, 1948–

Reading with meaning : teaching comprehension in the primary grades / Debbie Miller.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-57110-307-4 (alk. paper)

1. Reading (Primary) 2. Reading comprehension. I. Title.

OB1525.7 .M55 2002

372.4—dc21 2002017594

Cover photographs by Debbie Miller and T. John Hughes (center photo)

Cover and interior design by Martha Drury

Manufactured in the United States of America on acid-free paper

06 05 04 03 02 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

To the Public Education and Business Coalition, an

organization whose commitment to education inspires us to

teach and learn with passion, rigor, and joy

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

This page intentionally left blank

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Foreword vii

In Appreciation xi

Prologue: It Doesn’t Get Better Than This 1

1 Guiding Principles 5

Establishing a Framework ■ Proficient Reader Research ■

Gradual Release of Responsibility

2 In September 15

Community: Creating a Culture and Climate for Thinking

■ Building Relationships ■ Establishing Mutual Trust

3 Readers’ Workshop: Real Reading from the Start 25

Book Selection: In the Beginning ■ Reading Aloud ■

Mini-Lessons ■ Reading and Conferring ■ Sharing

4 Settling In 39

Book Selection: Theirs ■ Evaluation: Mine ■ What About

Phonics and Word Identification?

5 Schema 53

Thinking Aloud: Showing Kids How ■ The First Schema

Lesson

■ Text-to-Self Connections ■ Making Meaningful

Connections

■ Thinking Through Text Together: An Anchor

Chart in the Making

■ Releasing Responsibility: Small-Group

v

Contents

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Work ■ Text-to-Text Connections ■ Schema Throughout

the Year

■ Evidence of Understanding and Independence ■

Schema at a Glance

6 Creating Mental Images 73

In the Beginning: Thinking Aloud ■ Anchor Lessons ■

Evidence of Understanding and Independence ■ Mental

Images at a Glance

7 Digging Deeper 93

Taking the Conversation Deeper ■ Book Clubs for Primary

Kids?

■ Making Thinking Visible ■ Taking the Learning

Deeper

■ Work Activity Time

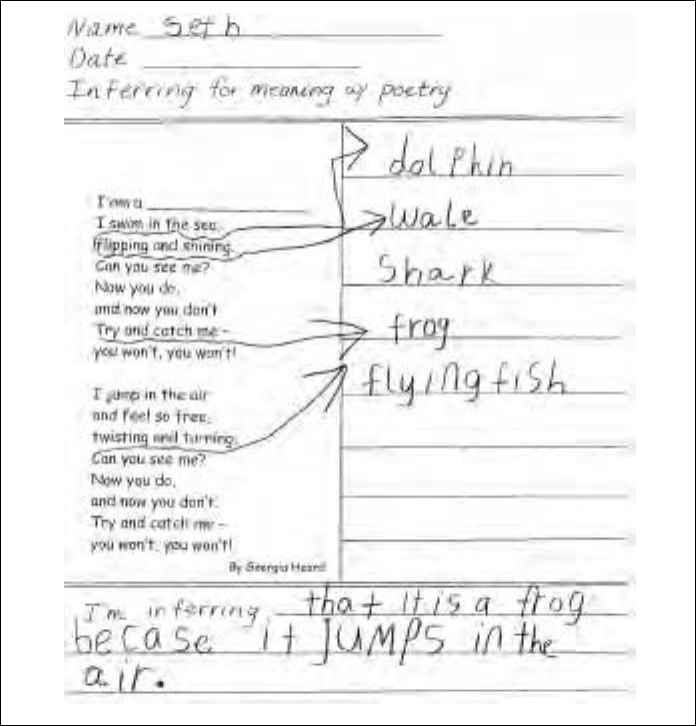

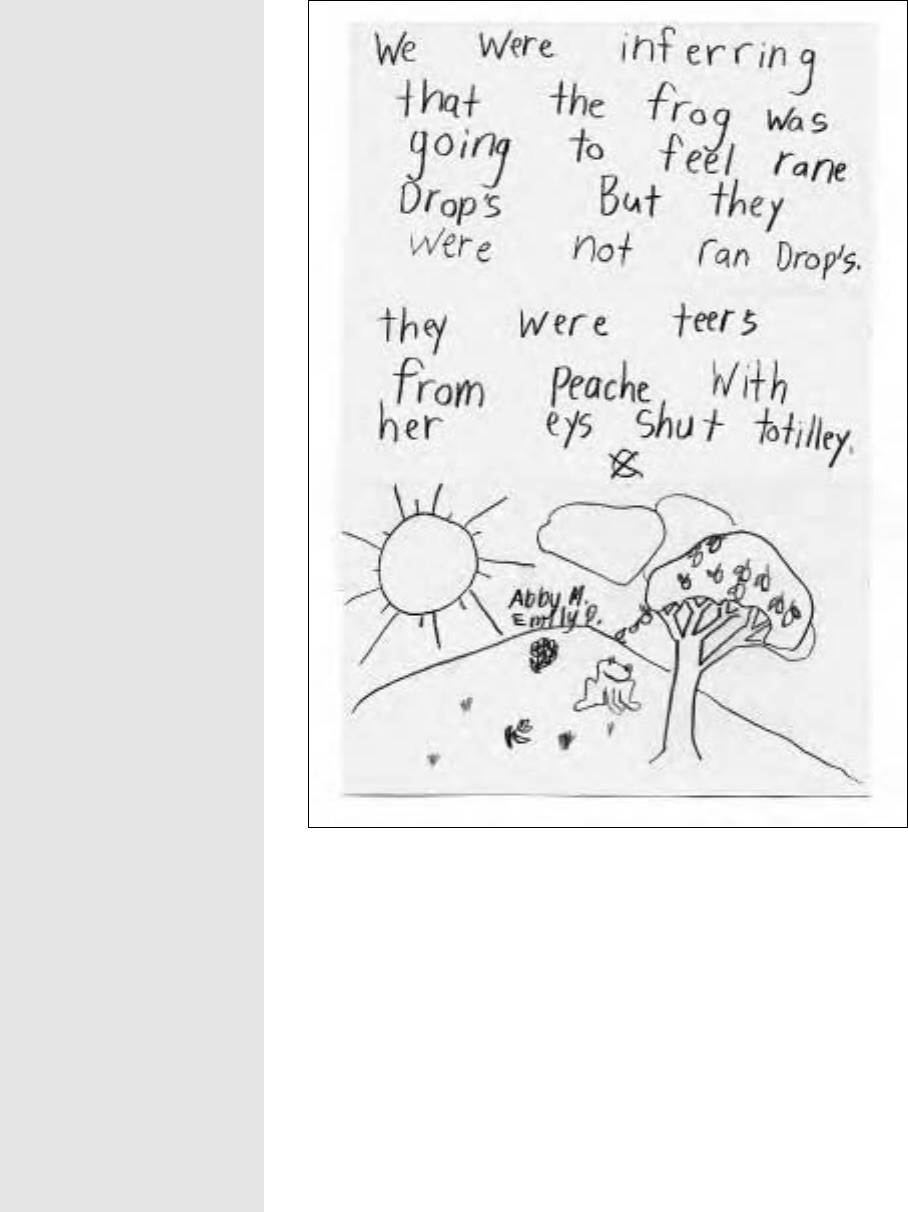

8 Inferring 105

Anchor Lessons ■ Evidence of Understanding and

Independence

■ Inferring at a Glance

9 Asking Questions 123

Anchor Lessons ■ Evidence of Understanding and

Independence

■ Asking Questions at a Glance

10 Determining Importance in Nonfiction 141

Modeling Differences Between Fiction and Nonfiction ■

Noticing and Remembering When We Learn Something

New

■ Convention Notebooks ■ Locating Specific

Information

■ Evidence of Understanding and

Independence

■ Determining Importance at a Glance

11 Synthesizing Information 157

Anchor Lessons ■ Evidence of Understanding and

Independence

■ Synthesis at a Glance

Epilogue: In June 173

References 175

Index 181

Reading with Meaning

vi

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

T

here is a mystique about fine primary teachers. There is something

transcendent about them—almost superhuman. As a young inter-

mediate teacher, I regarded the fine primary teachers in my build-

ing with something like bewildered awe. There was magic in the air down

their hallway: those teachers were teaching kids to read, and although I had

studied reading theory, I still couldn’t figure out how they could do it.

What were they doing? What was their secret?

When I approached the primary teachers I most admired and asked

them to describe how they taught kids to read, they were often unable to

articulate just how all the pieces came together. “I’m not sure,” they would

say. “I just know what to do. I follow the kids’ lead.”

When I first met Debbie Miller, my awe grew tenfold. Colleagues had

described the warmth of her classroom environment, the depth of her rap-

port with young children, the seamless way children managed their own

behavior in her classroom, her unconditional respect for each child. I

couldn’t wait to meet another fantastic primary teacher from whom I could

learn. But I discovered a profound difference between Debbie and the other

fine primary teachers I had known. When I asked Debbie about her beliefs,

her approaches, her teaching strategies, she was able to define and describe

not just what she did with children, but why.

Debbie began one of our early conversations by sharing a research-

based belief statement she had written to guide her practice. She laid out

what was working as well as what was puzzling her about the children. She

didn’t pretend to have the answers, but she knew that through study of chil-

vii

Foreword

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

dren and through professional study, she could explore and eventually artic-

ulate exactly why her children learned and responded in the way they did.

She was serious about her work in the classroom, but that indescribable

magic was there, too.

Debbie was everything my colleagues had described and more. There

was, however, one quality they hadn’t told me about, and it is one I have

come to believe is essential to her success. Debbie was, and is to this day,

absolutely fascinated by children. As I came to know her, I realized that she

finds nothing so enthralling as kids, and her uncanny ability to describe her

successes in the classroom rests on her ardent observation of them.

In Reading with Meaning Debbie gives language to the mystique of the

superb first-grade literacy teacher. Specifically, she explains the cognitive

tools young children need in order to understand. With a written voice so

like the one I now know from countless conversations, she describes with

humor, respect, awe, curiosity, and joy what it really takes to help children

explore and understand their world and the texts written to describe that

world.

Debbie articulates like no other teacher I’ve known what matters most

in primary literacy teaching and learning. She makes the indescribable

world of young learners clear and real. She also has a novelist’s gift for

detail. Every reader of this book will laugh and cry and wince and gasp—

and, perhaps for the first time, really understand early literacy.

In writing this book, Debbie has undertaken a daunting task: to

define and describe the thinking processes a young child uses to understand

and what a primary teacher can do to teach those processes. The task is

daunting not only because it is difficult to articulate fine practice, but also

because all too many people in this country, teachers and nonteachers alike,

don’t believe that young children are up to the task. Can a first grader, for

example, really synthesize as she reads? Come on. Can young children

determine importance? If they can, isn’t it a fluke? Will they do it again

later, with another book? Surely they won’t become independent in their

use of such strategies. Aren’t they really too young to think that abstractly?

Don’t we really need to focus on comprehension instruction in the upper

grades instead?

In Reading with Meaning Debbie not only provides conclusive evi-

dence that young children can think strategically when reading, she causes

us to rethink every assumption we ever had about what young children can

do. She shows how children from widely varying backgrounds and with a

huge range of needs can become aware of their own thinking during read-

ing, learn to give language to that thinking, and use it to understand any

Reading with Meaning

viii

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

text more deeply. She shows us how children have an almost infinite ability

to understand and discuss even the most abstract ideas.

How does Debbie get her children to think and write and read with

the kind of fervor you will read about in this book? She believes they can,

she shows them how a proficient reader does it, and she provides the means

to make their thinking public. She is focused, purposeful, and clear. But

there is another piece, at least as important. As Debbie tells us, there is not

enough joy in our classrooms and schools. Given all the public urgency to

perform and all the seriousness with which we now approach early literacy

learning, there has to be magic, a bit of fun, a lot of joy.

In Reading with Meaning Debbie uses the natural seasons of a teaching

year to reveal the gradual process of immersing children in a rigorous yet

intimate learning environment followed by ways in which she introduces

and develops a range of comprehension strategies. As you work your way

through the book, you will live through the school year alongside Debbie

and her kids, listening in, glimpsing the exquisite development of thought

and understanding. By the end of the book, the end of the teaching year,

you will see how these first graders have come to understand concepts of

extraordinary complexity and how they can use the comprehension strate-

gies independently and with great confidence.

It isn’t easy to explain great literacy instruction for young children. So

many fine teachers say, “I don’t know, it just comes naturally.” Debbie

shows us that by defining and teaching the cognitive tools we all use to

comprehend text, we give children the tools they need to think and under-

stand with unprecedented depth. In this book, which I believe will become

a classic in literacy teaching and learning, Debbie Miller defines and

describes the instruction, and she tells us about the children’s successes. But

there is always magic in the mix, a little mystique, a bit of fun, a lot of joy.

Ellin Oliver Keene

January 2002

ix

Foreword

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

This page intentionally left blank

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

W

e were hot, sticky, and short on patience as we filed into the fac-

ulty lounge one afternoon late in May. Lingering smells of pep-

peroni pizza, microwaved popcorn, and ripe banana mingled

with a fresh bouquet of lilacs. We had been summoned by our principal for

yet another faculty meeting. “What could it be this time?” we wondered as

we sank into the odd assortment of chairs that lined the room.

“Guess what, everybody?” Doris announced cheerily. “We are all

going to become writers this summer!” Eyes roll. Pencils tap. Tony, the PE

teacher, shakes his head and groans. Unfazed, the principal continues.

“Raise your hands if you’ve heard of Shelley Harwayne.” Three hands shoot

up. “Only three?” she asks, looking shocked and holding up as many fin-

gers. “Shelley who?” I ask.

We learn that Shelley Harwayne will be in Denver for one week in

June, giving a literacy workshop sponsored by the Public Education and

Business Coalition (PEBC), a nonprofit group committed to providing

ongoing support and leadership for schools in the Denver area. We are

required to attend.

Thank goodness! (I say now). What happened that week is hard to

explain, but it left me forever changed. I already liked being a teacher, but

in just five short days I began to think about children, learning, and teach-

ing in new and exciting ways. I became passionate about my work and pas-

sionate about learning, too. It was as though I’d been starving, so insatiable

was my appetite to learn more about the kinds of teachers and schools

Shelley described.

xi

In

Appreciation

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

I started to hang out in bookstores. Don Graves, Lucy Calkins, Connie

Weaver, Nancie Atwell, Regie Routman, and Shelley herself had me holed up,

reading and writing that whole summer long. I wrote in the margins and dog-

eared the pages of books, and I wrote notes and reflections in my brand-new

notebook. These authors’ words became my words; their visions for teaching

and learning became my visions, too. I couldn’t wait for school to start!

With the guidance and support of PEBC staff developers Steph

Harvey and Pat Hagerty, readers’ and writers’ workshops were up and run-

ning before the first snow fell. Gone were the “If I were a pencil” sentence

starters, basal readers, the bluebirds and the redbirds. And gone, too, were

the mile-high stacks of stapled work and activity sheets. I had taken, as

Shelley called it, “a leap of faith.”

Taking their place were literature and trade books, guided and indi-

vidualized reading, and opportunities for a wide range of responses.

Children were reading for longer periods of time than ever before, learning

to choose books to read that were just right for them, and flexibly using

strategies to figure out unknown words in the context of their reading.

Print covered the classroom walls, projects lined the window ledges and

spilled out into the hall. Life was good.

But then nagging questions started keeping me up at night. As I

planned for the week ahead, I’d wonder, “Am I really teaching kids every-

thing they need to know about reading?” I kept thinking that something

was missing; surely there must be something more for them, and me. I dis-

covered I wasn’t alone with these thoughts. Some of my colleagues had sim-

ilar concerns.

As if on cue, enter Ellin Keene. As director of the PEBC’s Reading

Project, she and other staff developers heard us. Through their collabora-

tion and expertise, a new model of reading began to emerge. Basing their

work on reading comprehension research, they showed us that we need to

teach children strategies for comprehension as explicitly and with the same

care as we teach them about letters, sounds, and words.

I’d found my something more. After years of collaboration with col-

leagues and work in the classroom, I have visions of my own now. And

words, too! The support and love of many have given me the courage to

write them down.

To Ellin Keene: you already know I think you’re brilliant! Thank you

for happily reading drafts over Saturday morning coffee, encouraging me

when I became discouraged, and being my friend through it all.

To my friend Steph Harvey, whose passion for learning exceeds that of

anyone I know: thank you most of all for teaching me to trust myself.

Reading with Meaning

xii

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Thank you, too, for introducing me to Philippa, and for advising me to

“cut to the chase” when that’s what I needed to hear!

To Anne Goudvis, who gently scaffolded me into the writing world:

thank you for your friendship, sharing your wisdom, and helping me with

citations at the very last minute.

To Chryse Hutchins: thank you for your encouragement and your

insightful work with teachers everywhere.

To Kristin Venable, PEBC staff developer, former teammate, and fore-

most my friend: now we can go back to Saturday morning coffee at Sisters,

walks on the Highline Canal, and baby-sitting, too! Thanks for helping me

with computer problems, book organization, and rantings about quitting.

To Kathy Haller: never stop e-mailing me, and thanks for facilitating

all those labs. (Maybe we should start one in Vail?)

To Patrick Allen, Leslie Blauman, Mary Urtz Buerger, Bruce Morgan,

Carol Quimby, Cris Tovani, and Cheryl Zimmerman, gifted teachers and

staff developers who share their work and their classrooms with others on

what sometimes seems a daily basis: I’m honored to know and work with

you.

To Barb Volpe, Judy Hendricks, and to all those, past and present,

whose leadership and commitment have made the PEBC what it is today,

I’ll always be grateful.

To Philippa Stratton at Stenhouse: thank you for your patience and

knowing just when to call and exactly what to say to nudge me forward.

(And still it took me forever!) Also thanks to Brenda Power for her kind

words and encouragement, Martha Drury for her exquisite sense of design,

and Tom Seavey for his marketing expertise.

To Kathy Nutting and many others at Regis University: thank you for

a wonderful master’s program and for supporting my efforts to make

explicit my beliefs about children, learning, and teaching.

To my colleagues and friends at Slavens: you inspire me every day with

your wisdom, energy, and love of children, teaching, and learning.

To Barb Smith: thank you for hours of listening, sharing ideas, and

responding to my work with honesty. I love that my kids get to go to you

for second grade—you always know just where to take them next.

To Michelle DuMoulin: thank you for hosting labs with me and being

such a thoughtful teammate.

To Valerie Burke: thank you for your encouragement and for sharing

your stash of caramels!

To Sue Kempton: thank you for years of collaboration and friend-

ship.

xiii

In Appreciation

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

To Peggy Fuller: thank you for the many things you do for Slavens,

especially in the classroom. You lighten my load and let me do what I love

most.

To Joy Lowe: thank you, girlfriend, for bringing light and laughter to

our school, taking such good care of our kids when we’re gone, and teach-

ing us not to take ourselves so seriously.

To Charles Elbot, the principal of Slavens Elementary School: thank

you for supporting me in my efforts to write and teach at the same time,

and for giving all of us the freedom to teach with our heads and our hearts.

To the parents of Slavens students: thank you for your care and

encouragement, for trusting me to love and teach your children well, and

for your support of my writing.

To Darby Shaw: thank you for your interest in my work and for being

there the day I needed you most.

And kids: I love you! You already know that. But did you know you

are the reason I love coming to work? Did you know I learn just as much

from you as you do from me? And did you know that it was your smart

thinking that helped me write this book? You did? Good job!

To my very own children, Noah and Chad: I love you and am so

proud of the young men you have become. Being your mom is my greatest

reward.

To Don, my husband and best friend: I love you, babe! Thank you for

taking photographs, reading drafts, cooking, cleaning, and shopping so I

could write, and having faith in me even when I didn’t. And most of all,

thank you for loving me, thirty years and counting!

And in memory of my mother, Joyce Everhart, whose own love of

teaching never left me wondering what I wanted to be when I grew up.

Reading with Meaning

xiv

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

1

It Doesn’t

Get Better

Than This

N

ew crayons in bright red baskets sit at the children’s tables, flank-

ing caddies filled with sharpened pencils, markers, scissors, and

glue. The pencils stand tall, their erasers intact. All sixty-four

crayons point in the same direction. Markers fresh from familiar yellow and

green boxes have their lids capped tight. And the glue comes out of its dis-

penser with an easy twist of its orange cap and a gentle squeeze.

A basket of songbooks sits atop the small clusters of tables. Each holds

one or two copies of Five Little Ducks, Oh, a Hunting We Will Go, Little

Rabbit Foo Foo, Twenty-Four Robbers, Dr. Seuss’s ABC’s, My First Real Mother

Goose, Chika Chika Boom Boom, The Lady with the Alligator Purse, and

Chicken Soup with Rice. Assorted fairy tales, picture books, volumes of

poetry, and nonfiction text round out the selection.

In the meeting area, an old floor lamp and several small table lamps

glow softly, their shades decorated by children from years past. Plants that

have survived the summer are back home on the window ledge; paper flow-

erpots stick to the windowpanes, waiting for children to paint their bou-

quets. Empty picture frames await the smiles of this year’s girls and boys.

Low bookshelves filled with books sorted into labeled tubs define the

meeting area; ABC books sit alongside Arnold Lobel and Henry and

Mudge; space and underwater books nestle with the reptiles; and tubs

labeled “Predictable Books,” “Song Books,” “Fairy Tales,” and “Little Bear”

join “Insects,” “Poetry,” and “Biographies.” Picture books stand tall on

shelves of their own.

Prologue:

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

The Kissing Hand by Audrey Penn, this year’s choice for the first day of

school read-aloud, stands ready at the chalk ledge. The rocker and the

braided rug await us.

The writing table seems to say, “Get over here!” Paper of all sizes and

colors, lined and unlined, duplicator and construction, lies straight in

organizers that are just the right size. Six staplers and as many tape dis-

pensers line the back of the table, with refills close by. Small containers hold

paper clips, pushpins, sticky notes, hole punches, and staple removers.

Dictionaries and thesauruses stand at the ready on the ledge behind.

Unifix cubes, pattern blocks, calculators, and bright yellow Judy

Clocks; microscopes, magnifying glasses, slides, maps, globes, and atlases

fill the shelves in the math, science, and geography areas.

Wooden blocks and Legos left behind years ago by my own children

occupy another shelf. Buckets of plastic dinosaurs, insects, reptiles, and

other assorted animals are ready for play. Nearby, small tubs labeled

“Pastels,” “Beads,” “Buttons,” “Yarn,” “Needles and Thread,” “Fabric,”

“Stuffing,” “Clay,” and “Watercolors” are stocked and ready for work activ-

ity time.

Professional books stretch from one end of my desk to the other.

Nancie Atwell and Gay Su Pinnell, Donald Graves and Marilyn Adams

coexist peaceably. Ellin Keene and Susan Zimmermann, Lucy Calkins,

Shelley Harwayne, Georgia Heard, Richard Allington, Brenda Power,

Ralph Fletcher, Brian Cambourne, Joanne Hindley, Ralph Peterson,

Stephanie Harvey, Anne Goudvis, Harvey Daniels, Connie Weaver, and

others join them and are there when I need their counsel.

My plan book is open, all subjects and specials penciled in and

accounted for. Paper for individual portraits, first-day interviews, and forms

for the Reader Observation Survey and Developmental Reading

Assessment are ready to go.

Yellow, orange, purple, and green magnetic letters march across the

radiator, spelling “Welcome to First Grade”; the class list is posted in the

hall under my nameplate. Sweetheart, Speedy, and Floppsey are fed and

their cages pristine. As I take one last look before I leave for the day, I won-

der, “Does it get any better than this?”

Twenty-four hours later I find myself under those same clusters of

tables, picking up stray Unifix cubes, assorted crayons and marker lids, two

butterfly barrettes, an animal cracker, and one small white sock with lace.

On the tables, the crayons have abandoned the caddies; pencils are mysteri-

ously dented and have mixed themselves in with the markers, and the glue

looks as if it’s had more than just a gentle squeeze.

Reading with Meaning

2

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

My desk is piled high. Registration forms, emergency cards, testing

dates, and memos from the office mingle with money and checks for the

PTA, today’s lunch, and school sweatshirts. Notes from parents request Girl

Scout information, an overview of this year’s curriculum, and the date and

time of the Halloween parade. Two more parents have written to let me

know their children are gifted.

I plop into my chair and take another look. This time I notice the tiny

bouquet of dandelions in the red plastic glass, the happy purple, orange,

yellow, and green chains that now hang from our doors, and the “I luv U

Mlr” written on the dry-erase board.

Magnetic letters that once marched across the radiator now dance,

spelling Mom, Dad, LOVE, Zac, cat, and IrNsTPq.

Yesterday’s empty flowerpots hold painted bouquets of what I think

might be daisies, roses, geraniums, and tulips. Children’s portraits with

their too-high-on-the-forehead eyes, crinkled paper hair, glued-on earrings,

and bright red lips smile back at me.

I read over their interviews. Hannah wants to learn to write her little

letters; Cole wonders why the octopus squirts ink. If they could do any-

thing in the world they wanted, Eric would be a fireman, Will would go to

the moon, and Jake would live in the theater district in New York City.

When I asked Grace, “What’s one more thing I should know about you?”

she answered, “You should know I believe in fairies.” And Breck’s answer? “I

really want you to teach me.” Now I know for sure. It really doesn’t get bet-

ter than this.

3

Prologue: It Doesn’t Get Better Than This

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

This page intentionally left blank

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Charting children’s

thinking makes it visible

and permanent and

traces our work together.

5

Guiding

Principles

1

Cory uses the same

format for Tut’s Mummy

Lost and Found by Judy

Donnelly.

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

W

hen I think about the principles that guide my teaching of read-

ing comprehension, I realize that they are the same principles

that guide my work throughout the day. Gradually releasing

responsibility to children as they gain expertise, teaching a few strategies of

great consequence in depth over time, and giving children the gifts of time,

choice, response, community, and structure guide my work and allow me to

make thoughtful decisions based on principles I believe in.

It was Brian Cambourne who encouraged me to make explicit my

beliefs about teaching and learning. He supported me and my colleagues at

Regis University as we explored the beliefs, theories, and practices of others,

considered their implications for teaching in general, tried out new prac-

tices in our classrooms, and finally synthesized and made explicit our per-

sonal beliefs about teaching and learning.

When we know the theory behind our work, when our practices

match what we believe, and when we clearly articulate what we do and why

we do it, people listen. At back-to-school night, when I get questions like

“Are you phonics or whole language?” or “My child is reading at the sixth-

grade level. How will you challenge him?” or “Do you believe in ‘invented

spelling’?” my stomach no longer churns. I know what to say. No longer are

my answers vague, my demeanor tentative, my attitude defensive. No

longer do I say things because it’s what someone wants to hear. I’m clear.

I’m confident. I’m calm. Parents appreciate and respect a teacher who

“knows her stuff,” even when it doesn’t quite agree with theirs.

Or maybe the district is thinking of adopting a new spelling program.

I can look at it and know fairly quickly if it’s something that I could work

with. When an administrator asks us about leveling all the books in our

school library or the new assistant principal asks us to dye our hair green if

children read a certain number of books, I really don’t have to ponder. I

know just what to say.

What if you are mandated to do something that you know in your

heart is not best for kids? Look at it carefully. Maybe there is a piece of it

that will work. As for the rest? Chances are, both your method and the new

one have the same goals; maybe you just believe in going after it a little dif-

ferently. Think about how you believe reading needs to be taught, and be

ready to thoughtfully explain how and why. Then make an appointment

with your principal and do it. Most administrators listen and support

teachers when we speak with conviction, know the research behind our

beliefs, and present our point of view in respectful, rational ways.

There are many effective ways to teach children and live our lives. No

one has a patent on the truth. Find yours. Read. Reflect. Think about what

Reading with Meaning

6

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

you already know about good teaching and how it fits with new learning.

Read some more. Think about the implications for your classroom.

Collaborate with colleagues. Try new things and spend time defining your

beliefs and aligning your practices. Once you’ve found what’s true for you,

stand up for what you know is right. Live it every day and be confident and

clear about why you believe as you do. People will listen!

Establishing a Framework

Think about yourself as a reader. You probably choose what you want to

read for a variety of purposes, have opportunities to read for long periods of

time, respond mostly through reflection, conversation, and collaboration,

and sometimes share your thinking and insights with others. In a readers’

workshop, children have daily opportunities to learn to do the same.

Structured around a mini-lesson (15–20 minutes), a large block of

time to read, respond, and confer (45–50 minutes), and a time to share

(15–20 minutes), the readers’ workshop format provides a framework for

both strategy instruction and the gradual release of responsibility.

The mini-lesson provides teachers with opportunities to think aloud

and show how strategies are used to make sense of text. The large block of

time for reading, responding, and conferring allows children to practice

strategies in small groups, in pairs, and independently, and gives teachers

time to teach, learn, and find out how the children are applying what they’ve

been taught. The share time gives children a chance to share their work as

well as an opportunity for reflection, conversation, learning, and assessment.

Sometimes visitors ask me, “You mean you have a readers’ workshop

every day? Don’t the kids get bored? Don’t you?” Yes, no, and no. The truth

is, I can’t imagine having a workshop only two or three days a week, or leav-

ing out a component here and there, depending on my mood. Such ques-

tions always draw my eye (and subsequently the visitors’) to the quote by

Lucy Calkins that hangs above my desk:

It is significant to realize that the most creative environments in

our society are not the ever-changing ones. The artist’s studio,

the researcher’s laboratory, the scholar’s library are each deliber-

ately kept simple so as to support the complexities of the work-

in-progress. They are deliberately kept predictable so the unpre-

dictable can happen. (1983, p. 32)

7

Chapter 1: Guiding Principles

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

To get started, find ninety uninterrupted minutes in your day and put

your readers’ workshop there. No time like that in the morning? Look at

your afternoon. I’d choose a big block of uninterrupted time in the after-

noon over a chopped-up morning any day. The workshop won’t run ninety

minutes until after the first four or five weeks, but teach well and you’ll be

amazed how quickly your children will get there!

Proficient Reader Research

When Ellin Keene, then director of programs at the PEBC, handed me a

copy of the proficient reader research synthesized by Pearson, Dole, Duffy,

and Roehler (1992), my eyes glazed over. Who were these guys, anyway?

And what did they know about teaching real kids in real classrooms? Yes, I

knew something was missing in my readers’ workshop. I’d been saying I

wanted rigor. And yes, I trusted Ellin. But come on! This stuff seemed way

too ivory tower to me.

The article was published in the early 1990s; researchers had spent

much of the previous ten years investigating what proficient readers do to

comprehend text, what less successful readers fail to do, and how to best

move novices toward expertise. From this work, Pearson et al. identified

comprehension strategies that successful readers of all ages use routinely to

construct meaning when they read and suggested that teachers need to

teach these strategies explicitly and for surprisingly long periods of time,

using well-written literature and nonfiction.

The research showed that active, thoughtful, proficient readers con-

struct meaning by using the following strategies:

■ Activating relevant, prior knowledge (schema) before, during, and

after reading text (Anderson and Pearson 1984).

■ Creating visual and other sensory images from text during and after

reading (Pressley 1976).

■ Drawing inferences from text to form conclusions, make critical

judgments, and create unique interpretations (Hansen 1981).

■ Asking questions of themselves, the authors, and the texts they read

(Raphael 1984).

■ Determining the most important ideas and themes in a text

(Palinscar and Brown 1984).

■ Synthesizing what they read (Brown, Day, and Jones 1983).

Reading with Meaning

8

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Sounds simple enough, right? But how exactly does one go about

teaching a few strategies of great consequence, in depth, over a long period

of time? Especially one who, after wading through the research, is seriously

wondering if she is a proficient reader herself?

I was always a fast reader, and therefore, I figured, a good one. In

school, I remember being among the bluebirds, flying high through story

after story, zipping through the questions at the end, and turning in pages

of neatly written seatwork with the pictures colored in just so.

But this stuff was different. What did they mean, think about your

thinking? I’m reading too fast to think. Interact with the text? Forget it; I

just want to find out what’s going to happen next. Draw inferences?

Determine importance? Synthesize? I’m not sure what those terms mean, let

alone know if I do them!

Still, I was intrigued. I wanted to learn more. And because of Ellin,

who recognized that the research had merit long before many of us did,

small groups of us began meeting once a week to try to make sense of it all.

Ellin understood that first we needed to learn about ourselves as readers.

She challenged us to be metacognitive—to think about our own thinking

as we read. We’d read books and short pieces, keep track of our thinking by

jotting notes in the margins, and then talk about the pieces and what we

were thinking as we read.

When we began to pay attention to what was going on inside our

heads as we read, we were amazed at what we learned about ourselves as

readers. We were making connections, asking questions, drawing infer-

ences, and synthesizing information. We began to create working defini-

tions for each of these strategies, realizing early on that the dictionary

definition was not going to cut it. (We fancied ourselves way beyond

Webster!) While friends chided us to “get a life,” we knew Ellin was right.

Only when we took the time to really get to know ourselves as readers were

we able to seriously consider the implications of the research for the chil-

dren in our classrooms.

Were we proficient readers all along? I’m not sure. Did all this height-

ened awareness simply bring to the forefront what was already going on

inside our heads when we read? Maybe. Regardless, I’m a different reader

now. I’ve learned to slow down and enjoy the ride; getting there no longer

consumes me. Ten years later, I’m still paying attention!

I find myself asking questions, inferring, making connections, and

smiling when I silently name what I’m doing. It’s not a loud, in-your-face

consciousness like it was in the beginning, but a soft, quiet, more natural

one, holding conversations with myself when I read.

9

Chapter 1: Guiding Principles

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

The proficient reader research has kept me in teaching. Not only was it

the “something missing” I’d been searching for, but it systematically raised my

expectations for children as well as for learning and teaching. And the best

part? Teaching isn’t as predictable as it once was. Every day I know children

are going to surprise me with their thinking, teach me to see and understand

things in new ways, motivate me to think deeply about my teaching, and help

me make thoughtful decisions about where to go next and why.

Gradual Release of Responsibility

Chances are that if you think back to a time when you learned how to do

something new, the gradual release of responsibility model (Pearson and

Gallagher 1983) comes into play. Maybe you learned how to snowboard,

canoe, play golf, or drive a car. If you watched somebody do it first, prac-

ticed under that person’s watchful eye, listened to his or her feedback, and

then one fine day went off and did it by yourself, adding your own special

twist to it in the process, you know what this model is all about.

Pearson and Gallagher use a model of explicit reading instruction

using these four stages that guide children toward independence:

1. Teacher modeling and explanation of a strategy.

2. Guided practice, where teachers gradually give students more respon-

sibility for task completion.

3. Independent practice accompanied by feedback.

4. Application of the strategy in real reading situations.

The table “Components of the Workshop” shows how the readers’

workshop provides the framework for teaching comprehension strategies

within the context of the gradual release of responsibility instructional

model.

Teacher modeling, or showing kids how, includes explaining the strat-

egy, thinking aloud about the mental processes used to construct meaning,

and demonstrating when and why it is most effective. Thinking aloud

about what’s going on inside our heads as we read allows us to make the

invisible visible and the implicit explicit.

Guided practice, or what I like to call “having at it” (it is also some-

times called scaffolding) consists of gradually giving children more responsi-

bility for using each strategy in a variety of authentic situations. Here, chil-

Reading with Meaning

10

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

dren are invited to practice a strategy during whole-class discussions, asked

to apply it in collaboration with their peers in pairs and small groups, and

supported by honest feedback that honors both the child and the task.

During independent practice, or the “letting go” stage, children begin

to apply the strategy in their own reading, ideally using real texts in real

reading situations. Teacher feedback through conferences is essential; teach-

ers need to let children know when they’ve used a strategy correctly,

encourage them to share their thinking with the teacher and their peers,

challenge them to think out loud about how using the strategy helped them

as a reader, and correct misconceptions when they occur.

Application of the strategy, or the “Now I get it!” stage, is evident when

children apply their learning independently to different types of text or in

other curricular areas. By this stage, children are more flexible in their

thinking: they begin to make connections between this strategy and others;

they can articulate how using a strategy helps construct meaning; and they

can use strategies flexibly and adaptively when they read.

So what does all this mean for kids? How can we help them find their

own soft and quiet voices? From my reading of the research, late-night and

after-school conversations with colleagues, and years of personal experience

11

Chapter 1: Guiding Principles

Components of the Workshop

Phases of Gradual

Release

Modeling reading

behavior

Thinking aloud

(showing how)

Guided practice

(having at it)

Independent practice

(letting go)

Application on their

own (now I get it!)

Time to Teach

15–20 Minutes

Read-aloud, Mini-lesson

Whole Group

✘

✘

✗

Time to Practice

45–50 Minutes

Reading, Conferring

Small Group, Pairs,

Independent

✗

✗

✘

✘

✘

Time to Share

15–20 Minutes

Reflection, Sharing

Whole Group, Small Group,

Pairs

✗

✗

✗

✗

✗

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

as a reader and a teacher, I’ve come to believe that I’m most successful at

teaching children to be active, thoughtful, proficient readers and thinkers

when I

■ have a deep understanding of the strategy being taught and am aware

of when and how it helps me as a reader.

■ think aloud using high-quality literature and well-written nonfiction.

■ gradually release responsibility for using each strategy.

■ confer with children regularly and offer honest feedback that moves

each child forward based on my knowledge of how proficient readers

use the strategy being taught.

■ use language that is scholarly and precise, creating a common language

for discussing books and ideas both in and out of the classroom.

■ teach each strategy separately and in depth, but show how one strategy

can build on another.

■ teach the reader, not the reading.

■ make thinking public by creating anchor charts that children can

refer to, add to, or change over the course of the year.

■ demonstrate how strategies can be applied to other curricular areas.

■ create an environment where reading is valued and seen as a tool for

gaining new knowledge and rethinking current knowledge.

How do you begin to plan for a six- to eight-week in-depth compre-

hension study using the gradual release of responsibility model? First, think

big picture. What’s your working definition of the strategy you’ll be teach-

ing? When do you use it? How does it help you? What do you think is key

for kids to know? Next, consider how you will define this strategy. What do

you want to say, and how will you say it? Remember, this is a working defi-

nition, meant to get you and your students started. It doesn’t have to be all-

encompassing or perfect—the children will help you with that!

Think, too, about what you believe is key to the strategy you’ll be

teaching. Break it down. What is it that you believe is most important for

kids to learn? This book can help you with that, but don’t leave all the

thinking to me! You’ll come up with different understandings that are

equally important.

Once you know what you want to teach, think about how you will

teach it. What books will you use to model your use of the strategy and the

points you want to make? How will you gradually release responsibility to

your students? How will you know if they are getting it? For this kind of

big-picture, long-term planning, I use a form (shown on the next page) to

Reading with Meaning

12

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

help me think about where I want my students to go and how I hope to get

them there.

I know it’s difficult just to think about planning a six- to eight-week

course of study—in fact, I used to think it was counterproductive. After all,

how could I possibly know where we’d be eight weeks from now? But this

isn’t about the day-to-day planning—that still needs to be done. Rather,

this “big picture” planning is about creating a well-thought-out, overall plan

that guides my work and gives direction to my day-to-day planning.

There’s nothing worse than walking into school each morning having

to figure out what to teach, scramble for a book, come up with a plan.

When we get caught in that trap, our teaching becomes disconnected, just

a series of lessons rather than a coherent plan for learning.

13

Chapter 1: Guiding Principles

Strategy Instruction Using the Gradual Release Model

Strategy

Time frame

High Teacher Shared Child

Low

Responsibility

✗

✗

High Teacher Shared Child

Low

Responsibility

✗✗

High Teacher Shared Child

Low

Responsibility

✗

✗

Modeling and thinking aloud

Shared experiences and guided practice

Independent practice

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Do I ever deviate from the big picture? Absolutely. I never know when

a child or a colleague will cause me to think about things in new ways, lead

me in new directions, and redefine my old thinking. As David Pearson said,

“Good planning, like good instruction, is as intentional as it is adaptable”

(Pearson, personal interview, 1995).

Reading with Meaning

14

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

15

In

September

2

Frankie’s response to the

question “What do we

know about books?”

Sharing a snack is

the perfect time for

practicing good manners

and the civility of

conversation.

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

I

t’s late afternoon. The children have gone for the day, and save for a

lone cricket chirping from his bug box in a faraway corner, the room is

quiet. It’s the second week of school, and despite vows that this year it’s

going to be different, that this year there really will be balance in my life,

I’m already feeling overwhelmed and out of sync. And instead of being

smart and heading out for the gym, or even staying to get ready for

Wednesday’s Back to School Night, score the district’s newest assessment,

or check my voice mail for the messages I know await me, I find myself

watching the sunlight as it streams in through the windows.

My eye catches a stack of letters peeking out from under a pile of

books. Realizing they’re the ones I’d asked parents to write, and mortified

I’d forgotten them in the rush of the first week, I sink (or is it slink?) into

the once-white overstuffed chair in the corner and begin to read.

I’d invited parents to take a few moments to write me about their chil-

dren, asking them to think about things that might be important for me to

know as well as their hopes and expectations for the coming year. As I read,

I learn that this year’s children are animal lovers, Irish step dancers, Kenny

Loggins enthusiasts, pianists, creative artists, Lego-maniacs, gymnasts, soc-

cer players, geniuses, and budding geniuses. They are dubbed silly, smart,

sweet, caring, serious, mature, young, sensitive, gregarious, shy, confident,

playful, and imaginative.

Matthew’s parents write that from the day he was born, he had a

sparkle in his eye, and now they do, too. They say that “more than any-

thing, Matt would love to read.” Caitlin’s family tells me they waited ten

years for her and that she is “the light of our lives.” And Danny’s parents

write, “we moved into the neighborhood because our dearest wish was for

you to be his first-grade teacher.” (Yikes!)

As I read the letters from the parents, I’m struck by the love between

the lines, the hopes and dreams that live in their words, and the faith and

trust they have in me. No one wrote that they wanted their child to score

high on the Iowa Test of Basic Skills, or attain Level 20 by the end of first

grade, or even meet the highly publicized state standards. It’s not that they

don’t want those things for their children, but the things they chose to write

me about—the things they considered most important for me to know—

were not about test scores, reading levels, or state standards.

I remind myself that in the incessant push for higher test scores, and

in the face of endless editorials about the demise of public schools and mis-

guided politicians and their plans for reform, I must not let myself—or my

budding geniuses—get caught up in some kind of frenzied, frantic pace

that knows no end. I remind myself not to let go of what I know is best for

Reading with Meaning

16

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

kids. For me, September is all about building relationships, establishing

trust, creating working literate environments, and getting to know children

as readers and learners—and remembering that our classrooms still need to

be joyful places where we take the time to appreciate Matthew’s sparkling

eye, Isabella’s shy poetic spirit, and Kendal’s boundless energy.

Community: Creating a Culture and

Climate for Thinking

If you had asked me about the importance of creating a sense of commu-

nity in my classroom ten years ago, I’d have said it was everything. I’d have

talked about the interviews and surveys we do at the beginning of the year,

the self-portraits taped above the chalkboard, the photographs everywhere

of children playing and working together. I’d have told you about Talent

Show Tuesdays, about writing and signing “Our Promise to Each Other,”

and about the children’s work that hangs not only on the boards and doors

but also from the wires that crisscross our room. I’d have told you about the

cozy spaces where children work in small groups, pairs, and independently,

and about rituals for birthdays, losing a tooth, and saying good-bye. And

finally, I’d have mentioned that each day begins with our singing “Oh,

What a Beautiful Morning” with Joanie Bartels, and ends with an a cap-

pella version of “Happy Trails to You” written by cowgirl Dale Evans.

And if you asked me about the importance of creating community

today? I’d still say it’s everything. But now I know that once the promises

are written and signed, the room beautifully and thoughtfully arranged,

and the photographs taken, developed, and sitting prettily in a frame, our

work has just begun. Real classroom communities are more than just a

look. Real communities flourish when we bring together the voices, hearts,

and souls of the people who inhabit them.

When our vision of community expands to create a culture and cli-

mate for thinking (Perkins 1993)—when rigor, inquiry, and intimacy

become key components of our definition—it’s essential that we work first

to build genuine relationships, establish mutual trust, and create working

literate environments. If we look to the months ahead and envision chil-

dren constructing meaning by spontaneously engaging in thoughtful con-

versation about books and ideas, asking questions that matter to them and

exploring their solutions, and responding independently to a variety of text

in meaningful ways, we must be deliberate in September.

17

Chapter 2: In September

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Building Relationships

I begin by paying attention to the little things. It’s noticing Paige’s cool new

haircut, Grant’s oversized Avalanche jersey, Kendal’s sparkly blue nail pol-

ish, and Cody’s washable tattoos. It’s asking about Palmer’s soccer game,

Jane’s dance recital, Elizabeth’s visiting grandpa, and Hannah’s brand-new

baby brother.

It’s giving Ailey a heart rock to add to her collection, copying a poem

about cats and giving it to Gina because I know she loves them, and even

putting a Band-Aid on Grace’s tiny paper cut. Showing children we care

about them and love being their teacher is an important first message. And

at the same time, I’m modeling for children how to show someone you care

about them; I’m modeling how you go about creating lasting friendships.

Teaching children how to listen and respond to each other in respect-

ful, thoughtful ways also helps foster new relationships and caring commu-

nities. I used to have long conversations with children about this, telling

them how important it was to listen carefully to each other and to really

think about what their classmates have to say. I’d talk about responding

respectfully, to look at the person you’re speaking to, call them by name,

and on and on. But the very next day a child might groan at a song another

had chosen, wildly wave a hand when someone else was talking, or flip

through the pages of a book while another child was sharing. And I’d go

into the whole respect routine again. During these conversations, the chil-

dren were just as eloquent. They sounded just like me! But their behavior

didn’t change. And I’d wonder, “What’s going on here? Why don’t they get

it?” And even sometimes, “What’s wrong with these kids, anyway?”

Eventually I realized, of course, that nothing was wrong with “these

kids.” They didn’t get it because I hadn’t shown them how. I’d told them to

be respectful, thoughtful, and kind, but I hadn’t shown them what that

looks and sounds like.

The best opportunities to show kids how occur in the moment. When

Frankie says to Colleen, “Colleen, could you please speak up? I can’t hear

what you have to say,” I can’t let that pass without making sure everyone

heard. I can’t let that pass without pointing out how smart it is to want to

hear what someone has to say. I say, “You guys, did you just hear Frankie?

Frankie, could you say that again?” She does, and I ask, “So boys and girls,

why was that such a smart thing for Frankie to do?” They respond, and

then I use their words and mine to bring our thoughts together.

And when Max tells Jack that his idea is “a little bit dumb,” I can’t let

that pass either. I say, “Max, I’m sure you didn’t mean to be rude to Jack,

Reading with Meaning

18

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

but when you said his idea was a ‘little bit dumb,’ that’s what you were

being. It’s okay to disagree with someone, but there are nicer, more polite

ways to do it. You might say something like, ‘Jack, I don’t understand what

you mean’ or ‘Jack, why do you think that?’ Try it again, Max.” He does,

beautifully this time, and I don’t miss the opportunity to let everyone know

how much we’ve learned from Max today.

Or Sean is trying to find a place in the circle, and he starts nudging

himself into a spot four inches wide. I say, “Sean, could you think of a bet-

ter way to get yourself into the circle?” Sean’s stumped. “Well, how about

this? The next time you need to be in the circle and there isn’t room, how

about asking someone to scoot back so you can fit in? Let’s try it right now.

Just say, ‘Sunny, could you please scoot back so I can fit in the circle?’” He

does. Next, I turn my attention to Sunny. “Okay, Sunny, Sean has asked

you nicely to scoot back. What could you say back to him?” She says, “Sure,

Sean, I’ll scoot back for you.” With smiles all around, she does.

Is the first time the charm? No. And probably not the third time

either. But remain diligent. Remain calm. Don’t give up the good fight!

Once the flagrant violations are in check, watch closely for the rolling of

eyes, the private conversations, the exasperated sighs. Don’t let those go by

either.

You can use these first lessons—we can call them “anchor lessons”—to

refer back to. For example, when Sarah snaps at Troy, I say, “Oops, Sarah,

what’s another way you could tell Troy what you’re thinking? Think back to

how Max handled something like this.” We’ll assist her if she needs it, but a

gentle reminder is usually enough.

Here are a few more teachable moments.

To the children with the wildly waving hand when someone is talking:

“You know what, guys? I know you’re not meaning to be rude, but when

your hand is up and someone else is talking, I’m thinking you’re probably

focusing on what you’re going to say rather than listening to the person

who is speaking. What do you think? Since we can learn so much from each

other, remember to keep your hands down and really listen and think about

what your friends are saying. When they’re finished, you can share what

you’re thinking.”

To the children who abruptly get up in the middle of a story or discussion:

“Oh my goodness, you’re going to leave us now? Think of the learning

you’ll miss! Can you wait until the story [or discussion] is over? Thanks.”

To the children who always have something to say, no matter the topic or

the day, and the ones who hardly have anything to say, ever: “Today I want you

to think about yourselves as listeners and speakers. If you’re someone who’s

19

Chapter 2: In September

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

great at talking a lot, I want you to be a listener today. See what you can

learn. If you’re someone who is a great listener, I want you to do some talk-

ing today. We want to know what you are thinking, too. Raise your hand if

you think you do a lot of listening. Raise your hand if you think you do a

lot of talking. Wow! You really know yourselves. That’s so smart. Let’s try

it.”

To those who have already heard every book in your library and can’t wait

to let you know the minute you hold it up: “That’s so great you’ve heard this

book before. And you know what? Since we know how much more we can

learn and understand when we reread, I want you to pay special attention

when you hear the story today. Think about what you notice this time that

you didn’t notice before. Think about what puzzled you the first time, and

what you think about that this time. Will you let us know?”

Doesn’t all this take a lot of time? You bet. But it sets the tone for

learning and thoughtful conversation; it paves the way for the work that lies

ahead. Once children realize you’re not going to relent, once they realize

that this is not just a “sometime thing,” and once they understand what you

want them to do and why it’s important, it becomes habit. It becomes part

of the language of the classroom.

Establishing Mutual Trust

Like building relationships, establishing trust takes time. And it must begin

with me, the teacher. Every time I value a child’s idea by acting on it, think

out loud to make sense of a question or response because I really want to

understand, or ask children what they think and then listen carefully, I let

them know I respect their thinking and trust that they have something

smart to say.

I don’t mean in a superficial “they’re only seven” kind of way; I mean

trusting children enough to give them the time and the tools to think for

themselves, to pose and solve problems, and to make informed decisions

about their learning. Respecting their ideas, opinions, and decisions doesn’t

mean carte blanche acceptance, but it does mean giving their voices sincere

consideration. Trust needs to be mutual. If we’re asking children to

thoughtfully consider the thinking of others, we must expect no less from

ourselves.

It was Lauren who made me a believer. It was early in her first-grade

year, and she’d been happily reading books like Whose Mouse Are You? by

Reading with Meaning

20

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

Robert Kraus and Cookie’s Week by Cindy Ward. But the day I read aloud

Mary Hoffman’s Amazing Grace, things changed. She had to have that

book. I gave her my usual line: “You know, Lauren, I’m thinking this book

is too challenging for you right now. How about waiting awhile, then giv-

ing it a try? You can keep it safe in your cubby until then. Let’s find Where

Are You Going, Little Mouse? I think that would be perfect for you.” But

she’d have none of the mouse. It was Amazing Grace she wanted.

In the end, she won me over. But once I’d said yes, I couldn’t just give

her the book and say, “You go, girl.” Once I’d relented, I needed to do

everything I could to help make her decision—now ours—a good one. I

had to figure how best to support her and maximize her chances for success.

This wasn’t about power or proving a point; this was about helping a little

girl learn to trust herself and make good decisions about her learning.

We made a plan together: I’d help her learn a page a day at school,

she’d reread what she’d learned already, and she’d take the book home every

night to practice. Five weeks later, the kids and I were calling her Amazing

Lauren! And she was amazing. Not only was she able to read Amazing

Grace, but she was off and running, reading books like Oliver Button Is a

Sissy by Tomie dePaola, Wild Wild Wolves by Joyce Milton, The Paper Bag

Princess by Robert Munsch, and Honey, I Love by Eloise Greenfield.

What if I’d said no? Would she have learned to read Oliver Button,

Honey, I Love, and the others? Probably. But I want to do more than teach

kids how to read. I want to teach them how to go after something if they

really want it, I want to teach them the rewards of hard work and determi-

nation, and I want to teach them that if they’re sincere, I’ll do everything I

can to support them.

If we expect big things from children, we must expect big things from

ourselves, too. For years I’d been told what to do in my classroom and how

to do it. Glossy teacher’s guides with smiling children on the cover even

told me what to say. I didn’t always read the words in italics exactly as writ-

ten (I considered myself a rebel even then), but I’d get the gist of the lesson

from the guides. Beyond running off worksheets and making cute activities

for centers, I never had to think much about reading at all. Come to think

of it, the kids didn’t either.

So when PEBC staff developer Steph Harvey blazed into my room

with a whole new way of thinking about children, learning, and teaching,

she made my head hurt. Every other week she’d come, lugging a tote bag so

full of books they left a trail behind her like Hansel’s crumbs of bread. She’d

do a fabulous demonstration lesson, we’d debrief over lunch, and then off

she’d go. “Wait!” I’d plead. “Can’t you leave me with a bit more of a plan

21

Chapter 2: In September

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

until you come back?” Just like my teacher’s manual, I wanted her to tell me

where to go next; I thought she knew more about my kids than I did.

But Steph was wise. She wouldn’t hand over any prescribed set of

mini-lessons. Instead, she’d say, “Come on, Deb. Think about what you

already know about good teaching. You know your kids. Where do you

think they need to go next?” Her best advice? “Trust yourself.”

Only when I began to assume responsibility for the teaching, learning,

and thinking in my classroom did I understand that I really did know my

kids, what they needed, and where they needed to go next. Only then did I

begin to believe I was smart enough to figure this stuff out for myself. I’d

had support from Steph, yes, but she’d made it clear the decisions were

mine to make. She’d trusted me before I’d known to trust myself.

And because she did, I wanted to live up to her expectations; I wanted

to be as good as she thought I was.

Actually, I wanted to be even better. I began to read more professional

books and articles, to join study groups, and to observe other teachers. I

worked long hours defining my beliefs and aligning my classroom practices;

I came to know the supporting research. I learned to believe in myself.

So what are the implications for the children in our classrooms?

They’re huge. When we show children we expect them to share thought-

fully in the responsibility for their learning, when we let them know we

believe they’re smart, and when we support them just enough so that they’ll

be successful, we’re doing for them what Steph did for me. We’re trusting

them first so that they can learn to trust themselves.

In my role as staff developer, teachers and others often observe our

readers’ and writers’ workshops. Invariably, someone will come up and

whisper, “You know, they really are talking about the book back in the cor-

ner over there.” (They think I’m going to be surprised.) Or they’ll wonder,

“So how do you know what your kids are doing if you don’t meet with each

one every day?” and “You mean they can just go up to the library all by

themselves?” I tell them what I’ve already told you; later we talk about get-

ting started.

Start small. Think about the things in your classroom that you do

automatically, without even thinking why. Ask yourself, “What am I doing

now that I could trust kids to do?” and “In what ways could I trust children

where I haven’t before?” Think about things like . . .

Do they really need to go to the bathroom and get a drink all at the

same time, or could children take care of those things on an individual

basis? Do I need to count and monitor the number of pretzels or animal

crackers they take for snack, or can I trust them to take two or three? Am I

Reading with Meaning

22

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

the only one capable of refilling the staplers and tape dispensers, and replac-

ing sticky notes, worn-out markers, and paper towels? Do I really need

elaborate and time-consuming check-out systems for books, CDs, markers,

videotapes, calculators, or whatever else children may want or need at

home? I say no. Not when we’re clear about what we expect and why. Not

when we trust kids enough to show them how.

23

Chapter 2: In September

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

This page intentionally left blank

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

25

Readers’

Workshop:

Real Reading

from the Start

3

Torin and Jack work

together to sound out

words.

Real literature by real

authors engages young

readers.

Reading with Meaning: Teaching Comprehension in the Primary Grades by Debbie Miller. Copyright © 2006.

Stenhouse Publishers. All rights reserved. No reproduction without written permission from publisher.

T

he voice of Joanie Bartels singing “Oh, What a Beautiful Morning” is

the signal for children to finish selecting their books and gather in the

meeting area. By the last “I’ve got a beautiful feeling, everything’s

going my way,” everyone’s singing along with Joanie. Readers’ workshop in

first grade is in full swing. We’ve been at it for almost three weeks now, and

children have learned how to select their books for the day, how to gather for

a story and mini-lesson, how to practice reading behaviors in authentic situa-

tions using real books, how to use workshop procedures, and how to share

with their classmates what they’ve learned about themselves as readers.

“Hold the phone,” you might be thinking. “How could they learn all

that in just three weeks?” or “How can you have a readers’ workshop when

they can’t even read?” Hang on. The fact is, most children haven’t learned to

decode or comprehend. Not yet. And still, they see themselves and their

classmates as readers. They clearly look the part, and right now, that’s pre-

cisely the point.

Readers’ workshop in September is less about teaching children how

to read and more about modeling and teaching children what it is that good

readers do, setting the tone for the workshop and establishing its expecta-

tions and procedures, and engaging and motivating children to want to

learn to read. Once these are in place, we can move forward quickly with-

out the distraction of management, procedural, and behavioral issues.

Rigorous environments do not have to be rigid or restrictive. I know

we have mandates, time lines, and important tests to give. And still I say

slow down! Learning to read should be a joyful experience. Give children

the luxury of listening to well-written stories with interesting plots, singing

songs and playing with their words, and exploring a wide variety of fiction,

nonfiction, poetry, and rhymes. Let them know when they say or do some-

thing smart; give them credit and ask them to share. Help children access