A NATIONAL ROAD MAP

FOR INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT

Revised September 21, 2018

INTRODUCTION

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is a sustainable, science-based, decision-making process that

combines biological, cultural, physical and chemical tools to identify, manage and reduce risk from

pests and pest management tools and strategies in a way that minimizes overall economic, health

and environmental risks. Pests are defined as any organism (microbes, plants or animals) that poses

economic, health, aesthetic or environmental risk. Pests are context-specific, so an organism that

is a pest in one environment may be benign or beneficial in others.

IPM uses knowledge of pest and host biology, as well as biological and environmental monitoring,

to respond to pest problems with management tactics and technologies designed to:

• Prevent unacceptable levels of pest damage.

• Minimize the risk to people, property, infrastructure, natural resources and the

environment.

• Reduce the evolution of pest resistance to pesticides and other pest management

practices.

IPM provides effective, all-encompassing strategies for managing pests in all arenas, including all

forms of agricultural production, military landscapes, public health settings, schools, public buildings,

wildlife management, residential facilities and communities, as well as public lands including natural,

wilderness and aquatic areas. This National IPM Road Map identifies strategic directions for building

and maintaining research, education and extension programs that focus on IPM priorities for each of

these arenas. Examples of programmatic IPM principles for several federal agencies can be found in

Appendix 1.

The goal of the IPM Road Map is to increase adoption, implementation and efficiency of effective,

economical and safe pest management practices, and to develop new practices where needed. This is

accomplished through information exchange and coordination among federal and non-federal

researchers, technology innovators, educators, IPM practitioners and service providers, including land

and natural resource managers, agricultural producers, structural pest managers and public and wildlife

health officials. The IPM Road Map will be updated periodically by the Federal IPM Coordinating

Committee (see pp. 10-11) as the science and practice of IPM evolve, with continuous input from

numerous IPM experts, practitioners and stakeholders.

EVOLVING IPM CHALLENGES

Pest management systems are subject to constant change, and must necessarily respond and adapt to

a variety of pressures. Pests may become resistant to pesticides, whether they are conventional or

2

biologically-based, or adapt to crop rotation, trapping or other control methods. The evolution of

weed, microbe, and arthropod pest resistance is a complex problem with consequential costs to food

security and public health that requires innovative solutions. Coordination between federal agencies,

universities, communities and other stakeholders is needed to address the ecological, genetic,

economic and socio-political factors that affect development, communication and effective

implementation of IPM strategies and technologies to manage pests effectively, slow the rate of

resistance evolution, preserve existing control measures and create effective new approaches.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regularly reviews registered pesticides

and may restrict or cancel labeled uses when risks outweigh benefits. Environmental concerns,

consumer demands and public opinion can significantly influence pest management practices. New

and invasive disease-causing pathogens, weeds, vertebrate and arthropod pests are introduced more

frequently as global trade and travel increase. Changing environmental conditions pose new challenges

for maintaining effective pest management systems. Pest species expand their geographic and

temporal ranges, occurring in expanded areas and both earlier and/or later in seasons, in response to

changes in climate. Pest species interactions within and among trophic levels, and across landscapes,

must also be considered when IPM strategies are being developed. IPM practitioners must strive to

implement best management practices, using tools and strategies that work in concert with each other,

to achieve desired outcomes while minimizing risks. Current and evolving conditions necessitate

increased development and adoption of IPM practices and technologies. The National IPM Road Map

serves to make these transitions as efficient as possible.

IPM was originally developed to manage agricultural pests but expanded into new arenas as its success

in agriculture became clear. Federal, state and local governments now use IPM in residential,

recreational and institutional facilities, biosecurity and natural wildland areas. A successful IPM in

Schools program was created through state and federal cooperation, and many states and local

governments have adopted IPM policies.

An emphasis of the National IPM Road Map is to prioritize responses that mitigate the adverse impacts

of invasive species: non-native organisms whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or

environmental harm, or harm to human, animal or plant health (Executive Order 13751). The arrival

of invasive species often disrupts established IPM programs in the short-term, as emergency

responses are undertaken to limit potential damage caused by the species of concern until scientists

and practitioners become well-informed of the invasive pest’s biology and ecology and management

practices are developed and delivered. Invasive species are currently estimated to cause $140 billion

in economic losses annually. Some species act as vectors of parasites, viruses and bacteria, potentially

leading to the spread of human illnesses, such as Zika.

The impact of invasive species in natural and human-created environments received national attention

and federal support when Executive Order 13112 on Invasive Species was signed by President Clinton

in 1999 and updated in December 2016 by Executive Order 13751, Safeguarding the Nation from the

Impacts of Invasive Species. This Executive Order established the National Invasive Species Council

to ensure that federal programs and activities to prevent and control invasive species are coordinated,

effective and cost-efficient (www.invasivespecies.gov). Federal and state agencies are coordinating

efforts and developing programs and policies in this effort. IPM programs are continually under

3

development at all levels to minimize the impact of invasive pest organisms, which can disrupt

established and effective IPM practices.

IPM FOCUS AREAS

A primary goal of the National IPM Road Map is to increase adoption and efficiency of effective,

economical and safe pest management practices through information exchange and coordination

among federal and non-federal researchers, educators, technology innovators and IPM practitioners,

including pesticide applicators and other service providers. Pesticide safety education that teaches

pesticide applicators sound safety and stewardship practices in the safe and efficacious use of

pesticides is an important component of IPM programming across focus areas.

Production Agriculture

The priority in this focus area is the development and delivery of diverse and effective pest

management strategies and technologies that fortify our nation’s food security and are economical to

deploy, while also protecting public health, agricultural workers and the environment.

IPM experts, educators, practitioners and stakeholders expect pest management innovations will

continue to evolve for food, fiber and ornamental crop production systems that improve their

efficiency and effectiveness. IPM practices that prevent, avoid or mitigate pest damage have reduced

negative impacts of agricultural production and associated environments by minimizing impairments

to wildlife, water, air quality and other natural resources. Fruits, vegetables and other specialty crops

make up a major portion of the human diet and require high labor input for production. Agricultural

IPM programs help maintain high-quality agricultural food and fiber products, and coupled with

pesticide safety and stewardship practices, help protect agricultural workers, consumers and the

environment by keeping pesticide exposures within acceptable safety standards. Agricultural IPM

programs also extend to and consider pest management in areas beyond production field borders, to

places that can harbor or serve as a source of agricultural pests such as adjacent roadsides, rights-of-

way, ditches, irrigation canals, storage and processing areas, compost and mulch piles and gravel pits.

Natural Resources

Our nation’s forests, parks, wildlife refuges, military landscapes and other natural areas, as well as our

public land and water resources, are under constant pressure from endemic pests and aggressive

invasive species. Invasive pests diminish habitat quality by out-competing native species for resources,

reducing biological diversity, richness and abundance; impairing grazing lands for livestock and

foraging habitats for wildlife; and degrading or impairing many other uses of public lands, waters and

natural areas. Americans value, and spend large amounts of time, in natural and recreational

environments like lakes, streams, parks and other open spaces. Protecting the ecosystem functions,

aesthetic standards and values of natural resources and recreational environments is as important as

protecting public health and safety. IPM practices help minimize the adverse environmental effects of

pest species on our natural areas. As we move into the future, commonly used and accepted metrics

are needed to quantify the impact of IPM programs and practices in these environments.

4

Residential, Structural and Public Areas

For the general public, the greatest exposure to pests and control tactics occurs where people live,

work, learn and recreate. IPM programs for schools and public buildings are excellent examples of

successful education and implementation programs designed for institutional facilities. Priorities in

this area include enhanced collaboration and coordination to expand these programs to other public

institutions and infrastructure. Residential and commercial environments require different tools and

educational materials than schools, and multifamily public housing structures present particular

challenges, including addressing pest issues for people who are unable or unauthorized to manage

pests themselves. Expanding IPM programs in these areas would reduce human health risks posed by

pests and mitigate the adverse environmental effects of potentially harmful pest management practices.

Preventing and controlling bed bug and cockroach infestations in multifamily and public housing and

other built environments is a high priority.

POTENTIAL APPROACHES/STRATEGIES FOR STRENGTHENING IPM

Improve economic and social analyses of adopting and implementing IPM practices, including

assessing the benefits of practice adoption

Improving the overall benefits resulting from the adoption of IPM practices is a critical component of

the National IPM Road Map. Cost-benefit analyses of proposed IPM strategies should not be based

solely on the monetary costs, but also includes consideration of the efficacy of managing the target

pest, environmental and ecological health and function, aesthetic benefits, human-health protection

and pest resistance-management benefits. Additionally, the personal costs of adoption to end users in

terms of time management and other social costs must be considered.

Economics must be considered for IPM practices to be widely adopted and their benefits realized.

Risks and benefits need to be defined and determined. A major factor in the adoption of IPM programs

is whether the benefit to humans and the broader natural systems outweighs the cost of implementing

an IPM practice. Evaluation of short- and long-term risks and benefits is needed. Attention should also

be paid to understanding the social and cultural characteristics of pest management, because in some

systems risks and benefits cannot be monetized and in others the costs and risks of pest management

practices are primarily borne by one party and the benefits realized by other parties.

Reduce potential human health and safety risks from pests and related pest management

strategies

IPM plays a major role in protecting human health. Public health is dependent upon a continual supply

of safe, affordable, high quality food and fiber, often referred to as food security. IPM also protects

human health through its contribution to food safety by reducing potential health risks from food-

borne pathogens and reduced pesticide exposure, and further protects human health by reducing

populations of insect vectors that transmit diseases to humans. Mosquito and vector-abatement

districts across the country use integrated pest management practices to control potentially dangerous

5

disease vectors, while minimizing human and environmental pesticide exposure. Pesticide safety

training and certification programs also help limit the public’s exposure to pesticides.

Historically, the success of IPM adoption and implementation, and resulting benefits to the health of

humans and the environment, was measured by tracking annual changes in the amount of pesticides

used in the United States, measured in pounds of “active ingredient.” For many reasons, pesticide

usage reduction is an inadequate measure of IPM successes when used alone. Pounds of active

ingredient used per acre does not address the evolving nature of pesticide chemistries (differences in

frequency and rate of application, toxicity, modes of action or human exposure), nor does it consider

changes in the pest complex being managed, including the introduction of invasive species or

resurgence of native pests. Also, in many cases, routine usage data are not available.

IPM practices, technologies and innovations have helped pest managers have move away from

calendar-based spray programs to more informed use of integrated management combining pesticides,

biological, mechanical and cultural controls in a way that minimizes economic, health and

environmental risks. These innovations include advances in pest monitoring, use of predictive models

to target vulnerable pest life stages, new spray technologies to reduce off-target drift, new planting

systems, population-suppression strategies such as mating disruption, use of disease resistant cultivars

or weed seed bank management, advances in scientific knowledge of pest and host biology and

ecology, and use of biological controls, biopesticides and biotechnology.

Minimize adverse environmental effects from pests and related management practices

IPM programs are designed to protect agricultural, urban, and natural environments from the damage

incurred from native and non-native pest species while minimizing adverse effects on soil, water, air

and non-target organisms. IPM practices in agriculture promote healthy crop environments while

conserving organisms that are beneficial to those agricultural systems, including pollinators, natural

enemies and soil flora and fauna. By reducing non-target impacts, IPM helps maximize the positive

contributions that agricultural land use can make to watershed health and function and minimize the

impacts pest control can have on non-pest organisms. IPM practices, tools and technologies enable

land managers to target pest species while minimizing environmental risks to natural ecosystems.

Examples include using trained dogs for detecting marsh-destroying nutria or brown tree snakes in

cargo. Other examples include releases of Wolbachia-inserted mosquitoes to reduce risk of mosquito-

vectored avian diseases in the Hawaiian Islands and management of additional species on lands and

structures managed by many federal agencies.

RESEARCH, TECHNICAL DEVELOPMENT, EDUCATION, COMMUNICATION AND

IMPLEMENTATION

In order to continue IPM development and adoption, and increase the benefits it provides nationally,

it is critical to enhance investment in:

• New strategies and tactics for pest management.

• Public and private education infrastructure, including existing land-grant university IPM

and pesticide safety education programs.

• Communication about the importance and effectiveness of IPM.

• Adoption and implementation of IPM plans and programs.

6

Research Needs

The IPM toolbox is in a continuous state of evolution. Introduction of new pesticides, changes to

existing pesticide labels resulting from EPA registration review, the influx of invasive species,

development of new technologies, and federal, state and local fiscal constraints on funding all

influence the furtherance of IPM research. Research needs in IPM range from basic investigations of

pest and host biology to the development of new pest management strategies and tools, and their

integration into decision support systems.

Technical Development

While there have been dramatic improvements in pest management practices during the last four

decades, there continues to be a critical need for new options that provide effective, economical and

environmentally sound management of pests. Rapidly evolving molecular genetic approaches,

including genetic engineering, gene silencing, gene editing, gene-drive systems and other genetic-

based IPM practices are being developed. Geographic Information Systems that analyze layers of data

from computers, satellites, aerial photography, drones, soil sensors, crop sensors or handheld GPS

units are enabling new mapping capabilities and spatial analyses of soils, crop health and pest and

weed infestations to allow farmers to better predict pest outbreaks and identify problem areas within

their fields. Variable-rate technology tools provide growers with abilities to vary the application rate

of crop inputs, enabling more spatially and temporally targeted management of pests. Drift-reduction

technologies that enable more precise deposition of pesticides and reduce pesticide drift to non-target

areas are being developed and adopted. As these and other technologies are delivered, they are likely

to significantly impact IPM moving forward.

National research and technology development goals and objectives identified by the Federal IPM

Coordinating Committee include (non-prioritized list):

• Investigate local and regional climatic effects on all aspects of IPM.

• Determine pest biology and biotic/abiotic interactions to develop and deliver tools and

tactics to manage pests across all IPM arenas and localities.

• Develop management tactics for specific settings (including crops, parks, homes, forests,

natural landscapes, wetlands, infrastructure and workplaces) to prevent or minimize pest

damage.

• Develop diagnostic tools for identifying pathogens, arthropods, vertebrates and weed pest

species, and how they may differ in certain geographic areas and crops.

• Develop and deliver more rapid diagnostic tools for detection and management of pests and

pesticide resistance in pest populations, including aquatic pests, plant diseases, arthropods,

vertebrates and weeds.

• Develop low-risk suppression tactics, including use of biopesticides, biological control and

products of both traditional breeding and molecular genetic technology.

• Develop monitoring tools, action thresholds and suppression tactics and tools for existing

and emerging pests that vector human diseases.

• Develop efficacious suppression strategies that are cost-effective to implement.

7

• Develop a more thorough understanding of adverse non-target impacts of pest management

tactics and means of mitigating those impacts, including impacts on society and culture.

• Develop a more-thorough understanding of beneficial impacts of pest management

strategies, including impacts on society and culture.

• Expand web-based resources for IPM systems.

• Integrate postharvest pest management approaches for food and fiber products in both field

and storage.

• Develop and implement new pesticide chemistries and application technologies.

• Encourage and support the development of areawide IPM projects to more effectively

manage pests on regional or landscape scales.

• Encourage and support research that addresses barriers to the adoption of promising IPM

technologies like agricultural uses of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, social acceptance of

molecular genetic approaches, etc.

• Develop economic models for IPM that inform research on new pest management

strategies, as well as decision tools for growers to implement management.

• Develop research-based educational strategies for delivering IPM to practitioners.

• Investigate economic and risk-management models that consider the costs, benefits and

risks of IPM adoption.

• Encourage and support research to assess economic, environmental, health and social

barriers to, and impacts of, adoption of IPM.

• Evaluate and demonstrate the utility of precision agriculture technology to more accurately

monitor and evaluate pest presence and the evolution and spread of resistant pests.

• Evaluate and demonstrate the efficacy of precision agriculture IPM tactics deployed within

or across growing seasons and landscapes, including GPS-guided aerial or ground-based

sensing or imagery systems, alone or integrated with tillage; or precision delivery systems

to apply the right pesticide or microbial agent at the right dose, in the right place, at the

right time.

Education and Communication

A diverse and evolving pest complex requires a cadre of trained individuals with enhanced skills that

ensure human health, food security and environmental protection. It is important for practitioners to

have sound knowledge of pest and host biology, soil and ecosystems functioning, and to acquire new

skills to conduct research and implement IPM strategies using new technologies, including

biotechnology, reduced-risk pesticides, cultural practices, resistance management and biocontrols. It

is also important to have an interdisciplinary cadre of researchers and educators that includes natural

and social scientists and educators to engage practitioners in the process – this cannot be a top down

process. To be successful, effective IPM communication and education must be both ground up (end-

user led initiatives and communication of issues to the researchers and educators) as well as top down.

The end-user input is critical to identify problems as well as to develop innovative solutions.

Collaboration with pesticide safety education programs will ensure a significant number of applicators

are trained each year on topics critical to the safe use of pesticides. Additional training programs

should be implemented to educate and equip IPM practitioners with up-to-date information ranging

from basic IPM principles to advanced skills in various technical categories.

8

Significant effort and support is needed for IPM education programs at U.S. universities to ensure

training for the next generation of IPM scientists and practitioners. This effort should include outreach

to the public so that the challenges of pest management and the benefits IPM delivers across multiple

systems is better understood. Goals of this effort include:

• Create public awareness and understanding of IPM programs and their economic, health and

environmental benefits through education programs in schools, colleges and the workplace;

through organizations for education, mentoring and technical assistance initiatives for

beginning farmers and ranchers and similar programs; and through creative use of media, with

attention to underserved and disadvantaged populations.

• Ensure a multi-directional flow of pest management information by expanding existing and

developing new collaborative relationships with public- and private-sector cooperators,

including end-users.

• Spotlight successful IPM programs and practices at the local, regional and national level to

engender support and promote informed discussion and involvement from stakeholders and

consumers who understand the benefits of public investment in IPM.

Adoption and Implementation of IPM

IPM research, education and outreach must continue to be conducted and communicated between

federal, state and local partners to ensure widespread adoption and implementation of evolving IPM

practices. Outreach and education with the public is also critical. Promoting IPM practices and

technology, and communicating relevant information about the value of IPM to producers,

homeowners, land managers and the public, continues to be a major need. The following activities

will contribute to the adoption of IPM:

• Engage with user groups to understand the value and challenges of incentive programs, both

those existing and proposed, to adopt IPM practices. Develop user incentives for IPM

adoption reflecting the value of IPM to society and reduced risks to users. Work with existing

risk-management programs, including federal crop insurance, and incentive programs such as

the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program

(EQIP) and other farm conservation programs to fully incorporate IPM tactics as rewarded

practices.

• Research how best to provide educational opportunities for IPM practitioners to learn new

communication skills that improve their extension and outreach practices, and enable them to

engage new and unique audiences in ways that help overcome potential barriers such as

language, cultural sensitivities, lack of internet access, disabilities, etc.

• Improve public awareness and understanding of IPM programs and their economic, health

and environmental benefits.

• Leverage federal and state resources to enable on-site research, extension, education and

training for end users to ensure long-term adoption and implementation of IPM practices

including the safe use of pesticides.

• Develop ways to spotlight successful IPM programs, including areawide management efforts.

9

MEASURING IPM PERFORMANCE

Through policies, directives, rules, regulations and laws, federal, state and local governments place

high priority on accountability systems. Such systems are based on performance measurements,

including setting goals and objectives and measuring achievement. Federally-funded IPM program

activity performance can also be evaluated.

The establishment of measurable IPM goals and the development of methods to measure progress

should be appropriate to the specific IPM activity undertaken. Performance measures may be

conducted on a pilot scale or on a geographic scale and scope that corresponds to an IPM program or

activity. Examples of potential performance measures are:

Outcome: Effective IPM practices that are economical and lessen environmental risk are

adopted.

Performance Measures:

• Adoption of IPM Practices - Design and conduct surveys that document the adoption of IPM

practices specific to regional production concerns in specific crops or in the management of

specific pests.

• Impacts and Outcomes of IPM Adoption - Document and demonstrate the impacts and outcomes

of IPM adoption, including short- medium- and long-term changes.

• Economic, Environmental or Health Benefits - Evaluate IPM programs based on their ability to

improve economic, environmental or health benefits, and to project these economic results to a

regional or national basis that predicts large-scale impacts.

• Public Awareness - Develop measures of public awareness and acceptance of IPM.

• Training and Technology - Document educational training and technology adoption in IPM

programming that mitigates pesticide exposures and reduces the evolution of pesticide resistance.

Outcome: Potential human health risks from pests and the use of pest management practices

are reduced.

Performance Measures:

• Pesticide Exposure - Relate dietary exposure to pesticides to IPM practice adoption using U.S.

Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service Pesticide Data Program and any

other available data.

• Human Health Impacts - Document changes in human health impacts caused by pests (such as

asthma cases related to cockroach infestations, insect-vectored diseases, allergic reactions to

plants, etc.) relative to changes in IPM adoption.

Outcome: Adverse environmental effects from pests and the use of pest management practices

are mitigated.

Performance Measures:

• Endemic Pest Control - Document the changes in endemic pest levels and damage following

adoption and implementation of IPM practices.

10

• Invasive Species Damage and Invasion - Document the increasing or decreasing rates of incursion

and damage of selected invasive species following adoption and implementation of IPM

practices.

• Contaminants - Document reduction in the movement and accumulation of contaminants used to

manage pests and relate those to specific IPM tools and practices.

• Environmental Health Improvements - Document long-term improvements in environmental

health in local landscapes following adoption and implementation of IPM practices.

IPM LEADERSHIP AND COORDINATION

The Federal IPM Coordinating Committee (FIPMCC):

The FIPMCC was established in 2001 by USDA Secretary Ann Veneman. It is composed of

representatives of all federal agencies with IPM research, implementation or education programs, and

may include other public and private sector participants as appropriate. The function of the FIPMCC

is to provide interagency guidance on IPM policies, programs and budgets. A key responsibility of the

FIPMCC is to provide strategic direction for IPM by:

(1) Clearly defining, prioritizing, and articulating the goals of the federal IPM effort.

(2) Making sure IPM efforts and resources are focused on the goals.

(3) Ensuring that appropriate measurements toward progress in attaining the goals are in place.

The FIPMCC reports to the Secretary of Agriculture through the USDA Office of Pest Management

Policy. The national IPM effort stems from a partnership of federal governmental institutions working

with stakeholders on diverse pest management issues. Leadership, management and coordination of

these IPM efforts occur at many levels to more completely address the needs of stakeholders. The role

of the committee is to provide guidance in the establishment of goals and priorities for IPM programs

across all IPM focus areas. To achieve this, the FIPMCC regularly communicates with stakeholders,

including the Regional Integrated Pest Management Centers, land-grant universities and other public

and private entities.

The USDA-funded Regional IPM Centers play a major role in gathering information concerning

the practice and status of IPM, and in the development and implementation of an adaptable and

responsive National IPM Road Map. The Regional IPM Centers have a broad, coordinating role

in the communication and regional coordination of IPM.

Federal Membership of FIPMCC:

United States Department of Agriculture

• Office of Pest Management Policy

• Agricultural Research Service

• National Institute of Food and Agriculture

• Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service

11

• Natural Resources Conservation Service

• National Agricultural Statistics Service

• Economic Research Service

• Forest Service

Environmental Protection Agency

Department of the Interior

• National Park Service

• Bureau of Land Management

• Fish & Wildlife Service

Department of Defense

Centers for Disease Control

Department of Housing and Urban Development

General Services Administration

Agency for International Development

Smithsonian Gardens

By Invitation of FIPMCC

• Western Integrated Pest Management Center

• Southern Integrated Pest Management Center

• North Central Integrated Pest Management Center

• Northeastern Integrated Pest Management Center

• IR-4 Project

• National IPM Coordinating Committee

Concluding Remarks

The goal of the National Road Map for Integrated Pest Management is to increase the adoption and

efficiency of effective, economical and safe IPM practices. This is facilitated through information

exchange and coordination among federal and non-federal researchers, educators, technology

innovators, IPM practitioners and service providers, including land and natural resource managers,

agricultural producers, structural pest managers, and public and wildlife health officials. The IPM

Road Map is intended to be a living document that will be updated periodically by the Federal IPM

Coordinating Committee as the science and practice of IPM evolves, with continuous input from

numerous IPM experts, practitioners, and stakeholders. We hope that the information in the Road Map

is meaningful and timely, and will help inform the development and implementation of IPM programs

in the future.

12

Appendix 1. Principles of an Integrated Pest Management Program

Examples:

A. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior

B. National Park Service, Department of the Interior

C. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

D. U.S. Air Force

13

Appendix 1A.

PRINCIPLES OF INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT (IPM) - U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service, Department of Interior

These IPM principles are the foundation for pest management planning and implementation.

● Understand the site management objectives; establish short- and long-term

priorities. Decide on your site objectives for pest management; use Specific, Measurable,

Achievable, Realistic, and Time-based (SMART) objectives when choosing tools.

● Prevent species from becoming a pest at your site.

Prevention is the first line of defense against any pest species.

• Identify and monitor the pest species.

Know the life history and the conditions that support the pest(s).

● Understand the physical (air, water, food, shelter, temperature, and light) and

biological factors that affect the number and distribution of pests and any natural

enemies. Conserve natural enemies when implementing any strategy.

● Build partnerships and consensus with stakeholders, such as communities and

decision-makers.

● Review available tools and best management practices (BMP) for pest management.

Tools and strategies can include: 1) no action, 2) physical (manual and mechanical), 3)

cultural, 4) biological, and 5) chemicals.

● Establish the “action thresholds.”

Decide at the level of pests/damage you will implement a management action to control

the pest population.

● Obtain approval, define responsibilities, and implement preventive, BMPs and

control treatments in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, policies and an

Integrated Pest Management Plan.

● Practice adaptive management.

Evaluate results of implemented management strategies through authorized monitoring;

determine if objectives have been achieved, and modify strategies, if necessary.

● Maintain written records.

Document decisions and the treatments implemented, and record monitoring results.

● Outreach and education.

Inform staff of the pest management issues in and around the site, and prepare

informative materials for outreach to visitors and others, if appropriate.

14

Appendix 1B.

National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

11-Step Integrated Pest management Process

The Process

We use the following 11-step process to develop and implement an effective IPM strategy:

1. Describe your site management objectives and establish short and long term priorities.

2. Build consensus with stakeholders-occupants, decision makers and technical experts

(ongoing).

3. Document decisions and maintain records.

4. Know your resource (site description and ecology).

5. Know your pest. Identify potential pest species, understand their biology, and conditions

conducive to support the pest(s) (air, water, food, shelter, temperature, and light).

6. Monitor pests, pathways, and human and environmental factors, including population levels

and phenological data.

7. Establish "action thresholds," the point at which no additional damage or pest presence can be

tolerated.

8. Review available tools and best management practices. Develop a management strategy

specific to your site and the identified pest(s). Tools can include: 1) no action, 2) physical, 3)

mechanical, 4) cultural, 5) biological, and 6) chemical management strategies.

9. Define responsibilities and implement the lowest risk, most effective pest management

strategy, in accordance with applicable laws, regulations, and policies.

10. Evaluate results; determine if objectives have been achieved; modify strategy if necessary

(adaptive management).

11. Education and outreach. Continue the learning cycle, return to Step 1.

Questions to Consider:

Some important questions to consider while determining an effective IPM strategy include the

following:

♣ Is it a pest? (Is it interfering with your management objectives?)

♣ Is it a native or non-native organism?

♣ What conditions foster the pest?

♣ What management zone is it in?

♣ What are the chances of successful management?

https://www.nature.nps.gov/biology/ipm/Documents/11step_IPM_Process.pdf

15

Appendix 1C.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Principles of IPM

Traditional pest control involves the routine application of pesticides. IPM, in contrast:

• Focuses on pest prevention.

• Uses pesticides only as needed.

This provides a more effective, environmentally sensitive approach. IPM programs take

advantage of all appropriate pest management strategies, including the judicious use of

pesticides. Preventive pesticide application is limited because the risk of pesticide exposure may

outweigh the benefits of control, especially when non-chemical methods provide the same

results. IPM is not a single pest control method but rather involves integrating multiple control

methods based on site information obtained through:

• inspection;

• monitoring; and

• reports

Consequently, every IPM program is designed based on the pest prevention goals and eradication

needs of the situation. Successful IPM programs use this four-tiered implementation approach:

• Identify pests and monitor progress

• Set action threshholds

• Prevent

• Control

Identify Pests and Monitor Progress - Correct pest identification is required to:

• Determine the best preventive measures.

• Reduce the unnecessary use of pesticides.

Additionally, correct identification will prevent the elimination of beneficial organisms. When

monitoring for pests:

• Maintain records for each building detailing:

o monitoring techniques;

o location; and

o inspection schedule.

• Record monitoring results and inspection findings, including recommendations.

Many monitoring techniques are available and often vary according to the pest. Successful IPM

programs routinely monitor:

• pest populations;

• areas vulnerable to pests; and

16

• the efficacy of prevention and control methods.

IPM plans should be updated in response to monitoring results.

Set Action Thresholds - An action threshold is the pest population level at which the pest's

presence is a:

• nuisance;

• health hazard; or

• economic threat.

Setting an action threshold is critical to guiding pest control decisions. A defined threshold will

focus the size, scope, and intensity of an IPM plan.

Prevent Pests - IPM focuses on prevention by removing conditions that attract pests, such as

food, water, and shelter. Preventive actions include:

• Reducing clutter.

• Sealing areas where pests enter the building (weatherization).

• Removing trash and overgrown vegetation.

• Maintaining clean dining and food storage areas.

• Installing pest barriers.

• Removing standing water.

• Educating building occupants on IPM.

Control Pests - Pest control is required if action thresholds are exceeded. IPM programs use the

most effective, lowest risk options considering the risks to the applicator, building occupants,

and environment. Control methods include:

• Pest trapping.

• Heat/cold treatment.

• Physical removal.

• Pesticide application.

Documenting pest control actions is critical in evaluating success and should include:

• An on-site record of each pest control service, including all pesticide applications, in a

searchable, organized system.

• Evidence that non-chemical control methods were considered and implemented.

• Recommendations for preventing future pest problems.

https://www.epa.gov/managing-pests-schools/introduction-integrated-pest-

management#Principles

17

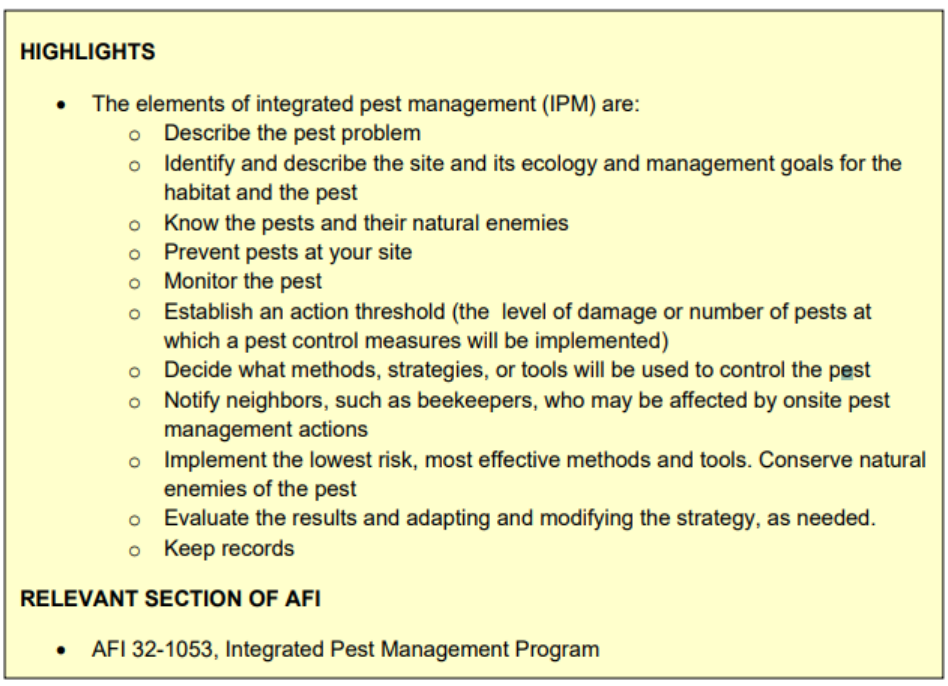

Appendix 1D. U.S. Air Force

From the 2017 U.S. Air Force Pollinator Conservation Reference Guide providing information to

supplement the U.S. Air Force Pollinator Conservation Strategy (Strategy) developed jointly by

Air Force Civil Engineer Center and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.