Best Practices

in Electronic

Records

Management

A Survey and Report on Federal Government Agency’s

Recordkeeping Policy and Practices

Prepared for

National Archives and Records Administration

Contract Number NAMA-M-0059, Task 0002

December 19, 2005

Center for Information Policy

College of Information Studies

University of Maryland

Lee Strickland, J.D.

Director, Center for Information Policy and Professor

Best Practices in Electronic Records Management

---

A Survey and Report on Federal Government Agencies’

Recordkeeping Policies and Practices

Center for Information Policy

College of Information Studies, University of Maryland

Sponsored in part by

The National Archives and Records Administration

Contract Number NAMA-M-0059, Task 0002

December 19, 2005

Abstract

This report presents the results of the Electronic Records Management Best Practices Survey

developed by the Center for Information Policy at University of Maryland with partial funding

from the National Archives and Records Administration. The survey collected data primarily

from twenty-one federal government agencies, two state government agencies, and one private

sector organization regarding their individual policies and practices for electronic records

management. The report provides information about the state of electronic records management

in federal agencies; describes barriers to improving the management of electronic records;

recommends strategies to improve management at the desktop; suggests approaches to

strengthen NARA’s role; and makes recommendations for future research based on questions

that arose during the course of the study.

Project Staff

Principal Investigator:

Lee S. Strickland, J.D.

Co-Principal Investigators:

Susan Davis, Ph.D.

Stephen Hannestad, M.A., M.I.M.

Consultant:

Bruce Dearstyne, Ph.D.

Graduate Student Researchers:

Megan Smith, M.L.S. candidate 2006

Juliet Anderson, M.L.S. 2005

Executive Summary

In order to propose solutions to problems encountered by many government agencies and private

businesses when managing electronic records created on desktop computers, the Center for

Information Policy at the University of Maryland completed a study to identify current and best

practices in electronic records management. The National Archives and Records Administration

provided partial funding, advice, and reviewed the study in draft. The findings and conclusions

are solely those of the research team, and do not necessarily represent our sponsors. The goal of

the research was to ascertain the extent to which federal government agencies have adopted

electronic recordkeeping systems and how the management of electronic records is incorporated

with traditional records management strategies. After completing research in the field, the ERM

research team refined the Electronic Records Management Best Practices Survey, based on a

draft survey provided by NARA, and administered the questionnaire in three phases:

Phase One – On-site interviews with employees from twenty-one federal agencies to

collect survey responses in-person.

Phase Two – A web-based survey directed at a larger audience of information

management professionals.

Phase Three – Phone interviews with records managers from two state government

agencies and one private sector business to gather information on recordkeeping policies

and practices for these sectors.

Methodology and Data Analysis

The Electronic Records Management Best Practices Survey consisted of fifty-five closed and

open-ended questions. The data gathered by the ERM Research Team from the on-site

interviews with federal employees (phase one of the project) was combined with responses

provided by records managers from two state government agencies and one private sector

business over the phone (phase three of the project). The on-site interviews allowed for an

extensive dialogue of actual practices at agencies as well as providing an opportunity to view a

demonstration of any electronic records management systems currently in place. Each survey

question was analyzed in detail and the full results (often displayed as a chart for clarification)

are included in this report.

A separate team of researchers from the Masters of Information Management Program at the

University of Maryland completed the web-based portion of the survey (phase two of the

project),; thus the results of were analyzed separately from the in-person and phone interviews.

The web-based survey (comprised of four sections: records management programs; paper

records; e-mail records; and electronic records) was available online for 30 days and results were

collected and analyzed from 119 participants. The web-based survey provided information on

electronic records management best practices in organizations beyond the Federal government

and was used as a basis for comparing and evaluating Federal practices.

Major findings of the Electronic Records Management Best Practices Survey:

During the survey administration and analysis of the resulting data from on-site and telephone

interviews, three major issues stood out to the researchers as problems encountered by the

majority of agencies interviewed:

1. Agency or office size affects the implementation of Electronic Record Keeping

Systems (ERKS); the larger the agency, the more complex the problems associated

with effective implementation.

2. Employees delete electronic records, such as e-mails, one at a time, a cumbersome

process which may result in retention of too many records for too long or premature

disposition that is inconsistent with approved retention schedules.

3. Many offices maintain dual, redundant recordkeeping systems – paper and electronic

– when all that is necessary is to maintain one record copy.

The nature of the survey also allowed the researchers to view and make note of strategies used

by some organizations to help solve these three significant problems. The researchers observed

and analyzed several techniques used by federal agencies, reviewed strategies and practices

advanced in the literature and used by other organizations, and then developed recommendations

which are intended to be effective and practical. Considering current financial resources, the best

option for Federal agencies until they are able to implement an official electronic recordkeeping

system is to synchronize their dual recordkeeping systems and simplify electronic records

deletion. This can be done by developing a file plan or classification scheme that describes

different types of files maintained in an office, how they are identified, where they are stored,

how they should be indexed for retrieval, and references the approved disposition. A sample file

plan and file structure example are included in this report.

Major findings of the web-based survey:

The web survey, included as Appendix E of this report, showed that full support of records

management policies by managers and supervisors is essential for their ongoing implementation.

Employees need to understand their responsibilities to implement those policies. E-mail is a

particularly important and ubiquitous form of electronic record but procedures for managing it

are underdeveloped. Lack of management support and employee understanding of records

management practices are major explanations for inadequate electronic records management in

general and, in particular, for the failure to implement electronic recordkeeping systems.

In conclusion, this report advises using a well-crafted, organized, and purposeful file plan as a

means to help alleviate problems transitioning to a full-featured ERKS. A meaningful media

neutral file plan that mirrors both electronic and paper files and follows the same maintenance

schedule will help to consolidate dual systems, assist with regular disposition, and prepare larger

agencies for the switch to an appropriate long-term solution.

Table of Contents

A Survey and Report on Federal Government Agency’s .................................................... i

December 19, 2005.............................................................................................................. i

Table of Contents................................................................................................................. i

Table of Figures..................................................................................................................ii

List of Tables .....................................................................................................................iii

List of Tables .....................................................................................................................iii

List of Samples ..................................................................................................................iii

Appendices.........................................................................................................................iii

Introduction......................................................................................................................... 1

Background..................................................................................................................... 2

Survey Methodology....................................................................................................... 4

Data Analysis.................................................................................................................. 6

Study Limitations............................................................................................................ 6

Questionnaire Results ......................................................................................................... 6

Introductory Section (1-5)........................................................................................... 7

Office Function and Organization (6-11) ................................................................... 8

Nature of Records (12-15)........................................................................................ 11

Agency/Office Records Management Program (16-21)........................................... 13

Records Management (22-24)................................................................................... 21

Paper and Electronic Records Maintenance (25-32) ................................................ 25

Maintenance of Electronic Records (33-37)............................................................. 32

E-mail Records and Web Content Management (37.5-44)....................................... 43

Future of Records Management and Concluding Remarks (45-55)......................... 49

Data Summary and Trends................................................................................................ 56

Introductory Questions (Questions 1 – 5)................................................................ 56

Office Function/Organization and Nature of Records (Questions 6 – 15) .............. 56

Records Management (Questions 16-24).................................................................. 56

Paper and Electronic Records Management and Maintenance (Questions 25-32)... 57

Electronic Recordkeeping Systems (ERKS) (Questions 33-37).............................. 57

E-mail Records (Questions 37.5 – 44)..................................................................... 58

Future of Records Management and Concluding Remarks (Questions 45-55)........ 59

Web Survey....................................................................................................................... 59

Key Problems and Proposed Solutions............................................................................. 61

Problem 1...................................................................................................................... 61

Proposed Solution..................................................................................................... 63

Problem 2...................................................................................................................... 63

Proposed Solution..................................................................................................... 65

Problem 3...................................................................................................................... 65

Proposed Solution..................................................................................................... 67

Future Research Opportunities ......................................................................................... 73

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 75

Acknowledgements........................................................................................................... 76

i

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Agency Categories .............................................................................................. 7

Figure 2: Level in Agency Hierarchy ................................................................................. 9

Figure 3: Records Staff to Total Staff............................................................................... 11

Figure 4: Records Series................................................................................................... 12

Figure 5: Records Date Span ............................................................................................ 12

Figure 6: Most Important Series....................................................................................... 13

Figure 7: Storage and Archiving....................................................................................... 16

Figure 8: NARA Training................................................................................................. 17

Figure 9: Usefulness of Training ...................................................................................... 17

Figure 10: Accountability & Enforcement ....................................................................... 18

Figure 11: Budget ............................................................................................................. 19

Figure 12: Rank of Records Manager............................................................................... 20

Figure 13: IT Development............................................................................................... 20

Figure 14: Government Acts............................................................................................. 21

Figure 15: File Plan........................................................................................................... 22

Figure 16: File Plan Specifics........................................................................................... 23

Figure 17: Records Schedule............................................................................................ 23

Figure 18: Flexible Scheduling......................................................................................... 24

Figure 19: Paper and Electronic Copies............................................................................ 26

Figure 20: Records Databases........................................................................................... 29

Figure 21: Location of Records ........................................................................................ 31

Figure 22: Offsite Storage................................................................................................. 31

Figure 23: Why Selected................................................................................................... 33

Figure 24: Who Files Records?......................................................................................... 34

Figure 25: Paper and Electronic Records.......................................................................... 35

Figure 26: Confidential and Sensitive Records ................................................................ 40

Figure 27: Program Worker Record Maintenance............................................................ 42

Figure 28: E-mail as a Record .......................................................................................... 43

Figure 29: E-mail Policy................................................................................................... 44

Figure 30: E-mail Format.................................................................................................. 45

Figure 31: E-mail and Employee Departure..................................................................... 48

Figure 32: Web Content.................................................................................................... 48

Figure 33: NARA Contact Information............................................................................ 49

Figure 34: Plans for an ERKS........................................................................................... 52

Figure 35: Conferences..................................................................................................... 53

Figure 36: Agency Communication.................................................................................. 54

ii

List of Tables

Table 1: Records Management Policy.............................................................................. 14

Table 2: Hold Orders ........................................................................................................ 15

Table 3: Media Used......................................................................................................... 27

Table 4: Reason Originals Kept........................................................................................ 28

Table 5: Official Recordkeeping Copy............................................................................. 29

Table 6: System Access.................................................................................................... 35

Table 7: Locating Electronic Files.................................................................................... 37

Table 8: Method Effectiveness ......................................................................................... 37

Table 9: Software and Hardware Migration ..................................................................... 39

Table 10: Disposition Practices ........................................................................................ 41

Table 11: Disposition Responsibility................................................................................ 41

Table 12: Destruction of Records..................................................................................... 41

Table 13: Permanent Electronic Record Procedures ........................................................ 42

Table 14: Records and Employee Departure.................................................................... 43

Table 15: E-mail Policy.................................................................................................... 44

Table 16: E-mail Record Location.................................................................................... 46

Table 17: E-mail Deletion................................................................................................. 47

Table 18: Custom-Built and COTS Problems .................................................................. 50

Table 19: Why Not an ERKS?.......................................................................................... 51

Table 20: ERKS Barriers.................................................................................................. 51

Table 21: ERKS Advantages............................................................................................ 52

List of Samples

Sample 1: Sample File Plan.............................................................................................. 70

Sample 2: Sample Shared Drive File Structures............................................................... 71

Sample 3: Sample Shared Drive File Structure Details.................................................... 72

Appendices

Appendix A: Electronic Records Management Best Practices Survey ............................ 78

Appendix B: Introduction Letter....................................................................................... 93

Appendix C: Informed Consent Form .............................................................................. 95

Appendix D: Opt-In Form …………………………………………………………… 97

Appendix E: Web Survey Report .....................................................................................99

Appendix F: Bibliography .............................................................................................. 120

Appendix G: Glossary.....................................................................................................130

Attachment: Survey Data by Respondent......................................................................134

List of Organizations Interviewed ..................................................................................154

iii

Introduction

The primary purpose of the Electronic Records Management (ERM) Best Practices

Survey was to identify current and best practices in the field of electronic records

management in order to make recommendations to the private and public sector on how

to manage records created on desktop computers. The ERM Research Team reviewed

current literature and previous studies in the area and refined a questionnaire drafted by

NARA to ascertain the extent to which federal agencies, state government agencies, and

private sector businesses have adopted electronic recordkeeping systems, and how the

management of electronic records is incorporated with general records management

strategies. After administering the questionnaire to employees from twenty-one federal

agencies, two state agencies, and one private sector business, the ERM Research Team

identified three major issues affecting the current state of electronic records management.

First, an organization’s size and resources determines its ability to implement or plan for

an Electronic Recordkeeping system [ERKS] (a system that uses records management

software which collects, organizes, and categorizes born-digital electronic records to

facilitate their preservation, retrieval, use, and disposition). Although there has been

much discussion of “ERKS,” an “official” definition of ERKS is not available, as the

concepts are still under development. However, for the purposes of this study, we have

used ERKS as being synonymous with Records Management Application [RMA]. DOD

5015.2-STD describes the required functionalities for a RMA. We do not apply the term

ERKS to such electronic records keeping approaches as (a) folders conforming to a file

plan on a shared drive; (b) a DMA which references approved dispositions, or (c)

individual electronic filing systems such as just maintaining e-mail on an employee’s

hard drive. As used in this report, an ERKS must comply with, DOD 5015-2-STD, but

does not need to be certified. Planning, developing, and implementing an ERKS requires

direction from managers, training for employees, and a commitment from everyone

creating records to make full and consistent use of the system. Providing the training,

motivation, and understanding on the part of employees is essential. The survey results

demonstrate that the majority of federal agencies currently using or in the process of

implementing an ERKS have less than 10,000 employees, which indicates that the

smaller the agency is, the further along it is likely to be in the process of adapting to

electronic records management.

Second, in the absence of an ERKS, disposition of electronic records is entirely manual

and unsystematic, meaning that employees select individual word-processing documents

or e-mail records and delete them one at a time without following established procedures

for reviewing and disposing of electronic records. This contributes to a problem found in

the study that organizations are retaining too many records past their disposition.

Third, the majority of organizations still designate paper as their official recordkeeping

format and most are maintaining a dual recordkeeping system where they retain the same

record in multiple formats, usually paper and electronic.

1

However, the interviews also revealed that many federal and state government agencies

are making concentrated efforts to control electronic records. Although only four federal

agencies which participated in the study are using or are in the process of implementing

an electronic recordkeeping system [ERKS] that meets DOD 5015 standards, nine are

using some type of software application that assists in electronic records management.

Many agencies without appropriate technology are using traditional records management

strategies to handle electronic records, such as following file plans to manage their

desktop files. The ERM Research Team evaluated current procedures in place at

organizations, alongside these three major issues, with the intent to propose a solution for

organizations not planning to build or purchase an ERKS in the immediate future.

The ERM team concluded that currently the best practice used by several organizations is

to synchronize their paper filing system with a central electronic filing system located on

a shared drive. This involves creating a detailed file plan that employees follow when

they file all records (regardless of format) and setting up a folder directory on a shared

drive that mirrors the arrangement of folders in a traditional filing cabinet. Using this

approach, an office would maintain electronic versions of records on a shared office hard

drive and paper records in a traditional paper file. Both sets of records would be filed the

same way, and both would be retained as long as indicated on the appropriate records

retention and disposition schedule. This solution does not fully address considerable e-

mail management problems experienced by most organizations and measured throughout

this study because it requires users to manually assign each e-mail to the appropriate file

folder. The research team suggests future studies should be done in the area of e-mail

management which builds on the information gathered by the Electronic Records

Management Best Practice Survey.

Background

Most organizations, including governments, today create their records on desktop

computers using word processing, e-mail, and various other types of software. The

reasons why organizations have adopted personal computers as essential tools to

complete work processes are obvious – computers allow documents to be saved,

modified, duplicated, stored, and transmitted electronically. Essentially, the convenience

of the personal computer has accelerated the pace at which organizations communicate

and produce results.

The benefits of using technology to create records have also resulted in complications for

many organizations trying to maintain and manage evidence of their business functions.

The ease with which documents are saved and duplicated by individual employees on

their desktops means that, potentially, many versions of non-essential and essential

records are retained and held for periods longer than required. It also increases the

likelihood that the records are being maintained according to individuals’ preferences and

conventions instead of records management principles. The volume of records and the

haphazardness with which they are managed produce more work for people trying to

2

locate specific records for accountability purposes, which can have huge legal

ramifications. Retaining an overabundance of records in electronic format also raises

concerns over the reliability, authenticity, and longevity of records because electronic

versions are easily changed, accessible by many employees within an organization, and

software platforms can rapidly become obsolete.

In addition to publishing literature, establishing guidelines, and creating canons of good

practices, the records management community has attempted to address many of these

issues by completing studies in electronic records management

, . Cohasset Associates

1

surveyed 2,206 individuals about their organization’s records management program in

2003. The questions in the Cohasset survey measured the level of importance

organizations place on records management by capturing information about the formality

of records management programs. The survey also evaluated employees’ perceptions of

the effectiveness of the records management policies and practices in place at their

organization. The White Paper produced from the survey demonstrated that many

organizations do not have effective records management programs. Organizations are

currently failing to manage their electronic records efficiently and are not prepared to

handle future electronic records compliance, legal, and preservation issues.

A study by SRA International

2

, which looked specifically at federal government agencies

and evaluated their recordkeeping practices, found results similar to the Cohasset survey.

SRA reported that while situational factors accounted for major variation in the quality

and success of recordkeeping, in general, records management is a low priority in federal

agencies, and employees do not know how to “solve the problem of electronic records.”

A key finding of the SRA study team was that agencies need and want guidance from the

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) on current records management

issues.

Despite the publication of standards by NARA, state archival programs, and other leading

records management professionals, many organizations are still puzzled over how to deal

with the management of electronic records and solve major problems documented in

reports such as the Cohasset survey and the SRA study. For example, the Sedona

Conference brought together experts from the legal field and produced The Sedona

Guidelines: Best Practice Guidelines & Commentary for Managing Information &

Records in the Electronic Age.

3

The Sedona guidelines contain excellent strategies for

implementing electronic records management policies and procedures, but do not provide

many practical solutions for day-to-day management of information in electronic formats.

1

See Robert F. Williams, Cohasset Associates Inc., “Electronic Records Management Survey – A Call to

Action,” Cohasset/ARMA/AIIM White Paper (2004). Available through Cohasset Associates,

<

http://www.merresource.com/whitepapers/survey.htm> [Accessed on 8/9/05].

2

See SRA International, Inc, Report on Current Recordkeeping Practices with the Federal Government

(December 10, 2001). Available through the National Archives and Records Administration,

<

http://www.archives.gov/records-mgmt/pdf/report-on-recordkeeping-practices.pdf > [Accessed on

8/9/05].

3

See The Sedona Guidelines: Best Practice Guidelines & Commentary for Managing Information &

Records in the Electronic Age, The Sedona Conference Working Group Series (September, 2005).

3

Many experts in the field are optimistic that the emergence of electronic records

management systems will reinforce records management guidelines, automate routine

functions, and help alleviate the burden of managing large amounts of electronic records.

Despite efforts to develop standardized practices and design software that can meet the

needs of organizations, electronic records management problems persist, many

organizations cannot afford to purchase or design technology that will solve their

problems, and the information management community is still uncertain of best methods

to ensure electronic records are properly captured, stored, and preserved.

The Electronic Records Management Research Team, co-sponsored by NARA, set out to

build on current research in electronic records management and identify, analyze, and

report on best practices in the field. The goal of the research project was to meet the

needs of organizations and NARA for effective strategies to manage electronic records

created and maintained by individuals on the desktop computer.

The project focused on how organizations can get control of electronic records with their

current resources and technology while considering how they might handle the increasing

complexity of electronic records management in the future. In order to build on previous

studies and make reliable suggestions, our research incorporated successful techniques

employed by Cohasset and SRA and surveyed outside organizations to determine current

policies, best practices, and employees’ perceptions about electronic records management

and records management in general. We also reviewed the records management and

archival literature on electronic records management and archival electronic records and

the recommendations of consulting and survey firms such as Cohasset and SRA.

Survey Methodology

The Electronic Records Management Best Practices Survey proceeded in four stages:

In the first stage, NARA contacted Federal records officers to solicit the participation of

his or her agency in the survey. NARA’s contacts yielded 21 Federal offices or agencies

that agreed to participate and NARA provided the University of Maryland’s ERM

Research Team with contact information for those offices. It should be noted that these

21 participants were simply offices that expressed a willingness to participate and thus

are not necessarily a representative sample of agencies. It should also be noted that many

agencies declined NARA’s invitation to be included in the survey. The reasons are not

certain and the project did not attempt to identify them. They may, however, have

included lack of time on the part of the records officer to participate in the survey and

apprehension about exposure of inadequate recordkeeping practices.

In the second stage, the ERM Research Team gathered data on the twenty-one federal

agencies to ascertain the extent to which agencies have adopted electronic recordkeeping

systems and how the management of electronic records is incorporated with traditional

records management strategies. The ERM Research Team completed on-site interviews

4

with federal agency employees using a structured questionnaire (Appendix A). At the

beginning of the project, NARA provided the Research Team with a model questionnaire

concerning agency recordkeeping and the Research Team modified it for use in the

survey. The interview questionnaire consisted of fifty-five questions, most of which

contained layered follow-up questions. The questionnaire was crafted in a way to allow

the flow of conversation to follow a natural course and make the participants feel

comfortable and open with sharing information about their office or agency. Many of the

questions consisted of multiple choice answers, but allowed for an option such as “other”

or “none of the above” or “don’t know” to allow the respondents to explain their

particular situation. Several questions were open-ended to allow participants to speak

freely and add extra comments about their procedures and policies regarding electronic

records management or records management in general. Performing the survey on

location allowed the Research Team to meet records staff in person and also facilitated

visual exploration and investigation of some of the records management methods being

practiced by the agencies visited. If electronic recordkeeping systems were in use by the

office, the research team asked for a demonstration of the system in order to get a feel for

how it worked. This “hands-on” approach provided an in-depth exploration of actual

practices at agencies. Two-thirds of the federal onsite interviews were also tape recorded

with permission (see Informed Consent Form in Appendix C) and reviewed again by the

research team for clarification of answers.

After completing approximately half of the twenty-one onsite interviews, the ERM

Research Team worked with a team of graduate students in Master of Information

Management Program at the University of Maryland to administer a web-based survey.

This second stage of the survey attempted to capture the same information as the federal

agency interviews but from a larger audience. Our purpose here was to deepen our

understanding of electronic records management problems, policies, and best practices

beyond the Federal government that participated in the interviews. It was sent to records

and information management professionals via records management and archives

listservs and consisted of a condensed version of the questionnaire used during the on-site

interviews (31 questions, 25 multiple choice, and 6 open-ended). The two teams decided

what questions to use based on the quality of answers supplied by interviewees during in-

person interviews; questions that yielded the most information were included. The

wording of the questions was only changed to make terms apply to a more universal

audience (i.e. agency was changed to organization) and questions pertaining only to

government agencies were omitted.

The final stage of the survey involved administering the on-site interview questionnaire

to two state government agencies and one private sector business. The two state agency

interviews were tape-recorded but the private sector business was not. This non-Federal

government sample was small but it provided valuable, first-hand insight into electronic

records management problems and practices.

5

Data Analysis

Analyzing the information collected at participating agencies consisted of several steps.

First, researchers typed any hand-written notes into a more legible format and clarified

any confusing answers by listening to tape recordings of interviews or contacting the

agencies after the interview for additional information. Next, the answers to the

interview questions were entered into a spreadsheet for comparison across agencies. For

the open-ended questions, or where the agencies provided additional data beyond the

scope of the initial question, the responses were categorized and grouped with similar

answers. And finally, data was analyzed across agencies and across questions to identify

similarities and differences or significant trends.

Study Limitations

This study, which included an extensive questionnaire, on-site interviews, and

considerable discussion and analysis, yielded invaluable insights about how electronic

records are actually managed and what can be done to strengthen that management. It

provides first-hand, empirical information. It actually yielded more information that we

have been able to include in this report. The project has a few limitations. The survey

covered only 21 Federal offices, which volunteered to be included, and it is therefore not

a statistically valid sample and the insights for a particular office can’t necessarily be

generalized to the parent agency as a whole. A few questions were disregarded when it

became apparent that their wording was not eliciting the intended level or type of

information, as noted in narrative below. The work focused primarily on electronic

records typically created by individuals on their desktop computers such as word

processing documents, it touched on databases and web content, but it did not attempt to

include a broader range of records such as digital images, sound bites, and instant

messaging records. Its findings and conclusions should be considered with those facts in

mind.

Questionnaire Results

The following questionnaire (see Appendix A) was administered during the first phase of

the research project, interviewing federal agencies, and the third phase, interviewing state

agencies and a private sector business. It is broken down into manageable sections for

easier reference and analyzed below.

The term “Not Applicable” or “NA” is used to refer to any of three situations. One,

offices provided that answer to indicate that a policy or practice did not apply to their

particular situation. Two, occasionally interviewers omitted questions. Three, sometimes

researchers felt that interviewees had not fully answered the questions but did not want to

repeat them.

6

Introductory Section (1-5)

The introductory questions of the survey were primarily used for information gathering

prior to site visits. The information was initially provided by NARA or researched by the

ERM team before attending interviews at each agency.

Question 1. What is the title and organization code of the office?

To maintain the anonymity of the offices that participated in this survey, each one was

classified by the type of category to which it belongs. Offices were identified as

belonging in organizations that fall into Defense and International Relations, Other

Civilian Agency, Infrastructure, or Environment

4

. Of the 24 offices surveyed, 6 were

classified as “Defense,” 7 were “Other,” 6 were “Infrastructure,” and 5 were

“Environment.”

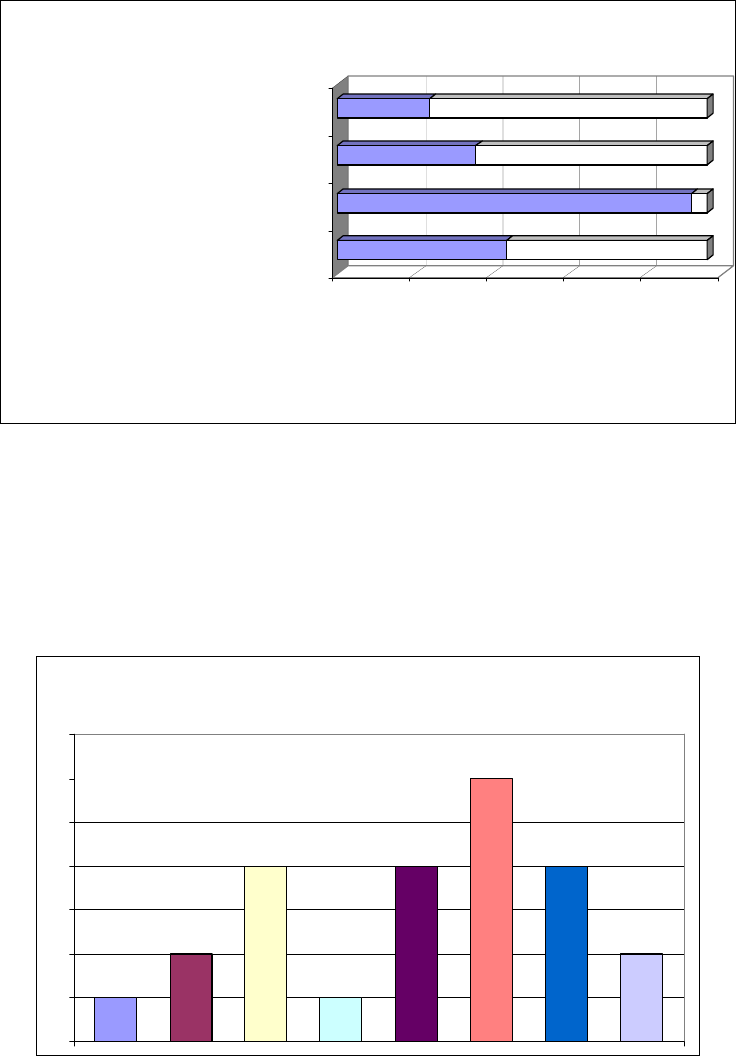

02468

Number of Agencies

Environment

Inf rastructure

Other Civilian Agency

Defense and

International Relations

Agency Categories

Figure 1: Agency Categories

Question 2. What is the name of the records management (or other) contact person for

this office? Was this person present during the interview?

This question is being omitted from the general analysis to protect the identity of those

agencies and representatives who opted out of being acknowledged as a participant.

Question 3. What is the office’s physical location?

Physical addresses were collected for each office visited or surveyed. Only the

breakdown of location by State is provided here.

District of Columbia: 9

4

Defense and International Relations: All defense, intelligence community, and diplomatic organizations.

Environment: Civilian organizations whose primary function is regulating environmental concerns or

maintaining parks, forests, public land, or other natural assets. Infrastructure: Civilian organizations whose

primary function is regulating or maintaining critical infrastructures, including roads, utilities, banking and

finance, transportation, and energy. Other Civilian Agency: All other civilian agencies.

7

Virginia: 8

Maryland: 4

Other: 3

Question 4. What is the primary function of the office?

While the office function is an important consideration when setting up and operating an

electronic recordkeeping system, the answers to this question were provided by NARA

solely to provide the interviewers some background information on the agencies visited

and further analysis was not pursued.

Question 5. Does the agency maintain a Federal public web site?

a. If yes, did NARA include the agency on its Active Agency Domains list as a

target for their harvest of Federal agency public web sites, as they exist on or

before January 20, 2005?

The researchers defined this as an agency that maintains a web site which is accessible to

the general public outside of government buildings and without logins and passwords.

All 24 agencies surveyed maintain a federal public web site. Information concerning

NARA’s inclusion of the sites in their harvest of public web sites prior to January 20,

2001 was incomplete as the researchers did not have access to the harvest list.

Office Function and Organization (6-11)

This segment of the questionnaire focused on the organization and makeup of the office

employees and the work performed regularly.

Question 6. What work does the office perform?

This question allowed the researchers to get an idea of the type of work the agency and

office carried out in order to place many of the survey questions in context for the

interviewees. The nature of the work performed by the offices varied significantly. The

differences between the various agencies’ missions and individual offices’

responsibilities are too complex to categorize the work function in a way that would

protect the identity of the agencies, while still eliciting useful information. The data

collected has been kept on hand for future reference or research at the Center for

Information Policy, but is not being analyzed in-depth for this report as it does not add to

the value of the study.

Question 7. What is (are) the functional title(s) of the program workers in the office

(e.g., action officer, management analyst, scientist, engineer)?

After results were evaluated from all surveys, the responses to this question were too

broad and cover too many areas to be of relevance. This question has been withdrawn

from any further evaluation, but the data collected has been kept at the Center for

Information Policy.

8

Question 8. What offices are above this office in the agency hierarchy?

Offices at the top of an agency hierarchy were designated as “I,” offices at the second

level as “II,” and so on. Offices at a level five down or lower were grouped together. The

majority of offices visited fell two to three levels down from the top of their agency.

3

6

7

4

4

01234567

I

II

III

IV

V+

Level in Agency Hierarch

y

Figure 2: Level in Agency Hierarchy

Question 9. How is this office organized internally (i.e., is it subdivided into branches

or other subunits)?

This is defined as the number of divisions or separate groups within the office, informal

or formal, as understood by the office and communicated to the interviewers. For

example, the Management and Budget office of the National Ocean Service (a division of

the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) is broken down into five

divisions: Policy Planning and Analysis, Information Management, Resource

Management, Special Projects, and Communications and Education. This particular

office would be assigned an internal organization of 5+ to represent the five divisions

within the office.

The answers are as follows:

7 offices had no splits

6 offices had 2 separate groups within the office

3 offices had 3 separate groups within the office

1 office had 4 separate groups within the office

3 offices had 5 separate groups within the office

1 office had 7 separate groups within the office

1 office had over 50 separate groups managed by the office

2 offices explained that this question was not applicable to their office or did not

answer the question

9

In addition to the number of divisions within the office, the researchers investigated the

size of each agency and corporation (by number of total employees) to attempt to gain an

understanding of the implications of records management for the agency as a whole. To

continue with the previous example, at the agency level, this number would represent the

number of employees at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and was

researched online if not provided by the interviewee. The agency size breakdown is as

follows:

0-100 employees: 3

101-1000 employees: 1

1001-5000 employees: 3

5001-10,000 employees: 4

10,001-50,000 employees: 7

50,001+ employees: 3

Unknown: 3

Question 10. Approximately how many staff members are in the office?

The number of staff members was evaluated much like the agency and division size but

on a more narrowly defined level. Again, to continue with the previous example, the

number of staff members in the office would be defined as the number of employees

working only in the Management and Budget Office of the National Ocean Service (to

include all five divisions). The number of staff members in the office by itself was not as

revealing to the researchers as was the comparison of staff size to the number of records

staff in the office. Please see question 11 below.

Question 11. How many records liaison staff does the office have?

Records staff or records liaison staff is defined as the number of people designated by an

office with responsibility for making decisions about the management of records in that

office.

The number of records staff (from question 11) was compared to the number of staff

members (from question 10) in the office as a means of determining the percentage of

employees within an office who are responsible for making decisions about records

management.

The results show the great variation in how responsibility for records management is

assigned in various settings. Nine offices – more than a third of those surveyed –

indicated that less than 5% of their staff have these responsibilities, while three offices

reported that over half of their staff have them.

10

Records Staff as a Percentage of Total Office Staff

9

7

2

2

3

1

0%-5%

6%-10%

11%-25%

26%-50%

51%-100%

N/A

Figure 3: Records Staff to Total Staff

Nature of Records (12-15)

The following few questions deal with the types of records created and received by the

office.

Question 12. What are the major titles of records series being maintained?

Survey respondents replied to this question with a great variety in answers. Almost all of

the survey participants listed multiple types of records. For ease in evaluation, records

series titles were grouped into one of four broad categories: Administrative, Program

Operation, Program Management, and, Information Services.

Administrative records are records relating to the administration of the office, i.e.

personnel records, office budgets, organizational charts, or general

correspondence.

Program Operation records relate to the actual work an office carries out in order

to fulfill its mission. These records are the actual work the office produces, i.e. if

the office’s primary responsibility is to formulate policy, then their policy records

would fall under program operation.

Program Management records relate to the administration of the office’s program,

or the maintenance of a particular project that fulfills their mission, i.e. project

plans or project budget.

All records relating to specifically to FOIA requests and Privacy Act records are

classified as Information Services as well as office or agency publications

managed by the office.

Agencies responded as follows:

11 out of 24 offices maintain Administrative records series.

23 out of 24 offices maintain Program Operation records series.

11

9 out of 24 offices maintain Program Management records series.

6 out of 24 offices maintain Information Service records series.

Note that any office may have a combination of all types of records but the results only

include those listed by the respondent.

0 5 10 15 20 25

Number of Offices

Administrative

Program Operation

Program Management

Information Services

Record Serie

s

Disbursement

Types of Records Series Maintained

Figure 4: Records Series

Question 13. Approximately what is the date span of records in the office?

(How far do they go back?)

The date span is defined as the earliest date of official recordkeeping copies which are

physically maintained in the office. The average date span maintained in each office is as

shown on the chart on the following page:

Date Span of Records Maintained

1940-1949

1950-1959

1960-1969

1970-1979

1980-1989

1990-1999

2000-present

depends /

unknown

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Figure 5: Records Date Span

12

Question 14. Which records does the office consider the most important?

The records deemed most important by an office were classified by the same broad

record series categories discussed in Question 12. If an office designated that all records

are equally important, this is represented by the category “all.”

Following are the results by survey participants:

Most Important Records Series

0

1

5

0

1

12

2

3

Administrative

Prog Ops and Admin

Program Operation Alone

Program Management Alone

Program Ops and Mgmt

Information Services

Don't Know

All

Figure 6: Most Important Series

Question 15. Which records does the office send to other offices, either inside or outside

of the agency (e.g., the office submits quarterly activity reports to the Office of the

Secretary)?

The wording of this question elicited inconsistent responses from participants. Some

respondents answered with a “yes” or “no” reply, while others listed specific reports or

documents by name that are sent to other offices. Due to varying and confusing answers

from survey contributors, this question has been withdrawn from any further evaluation.

Agency/Office Records Management Program (16-21)

The following questions are concerned with the general components of a typical records

management program and aim to determine which policies and procedures are currently

in place.

Question 16. Please describe the records management program in this office:

Due to multiple segments of this question, the answers provided by survey participants

are provided below in tables or charts. Question segments have been combined where

possible. Majority answers for each category have been highlighted with bold text.

a. Is there a written records management policy?

13

Defined as an official records management policy currently in use by the

office. An official policy may be on an agency level, an office level, or a

combination of both. A draft or “in process” policy is not considered official

for the purpose of this survey. Results are below.

b. Is there a component of the written records management policy that addresses

electronic records?

Defined as a component of an official records management policy which

addresses electronic records (see written records management policy above).

A total of 20 offices explained that they have some form of written records

management policy (whether agency-wide, office-specific, a combination of

agency and office defined, or just designated as a written policy by

respondents) with three other offices explaining they were in the process of

developing a policy. Of the 20 offices which had a written policy (in

whatever form), a total of 17 offices stated their policy addressed electronic

records (two of which specified that this electronic reference was specific to

just their office). The complete results are below.

Table 1: Records Management Policy

Written RM

policy

Addresses

electronic records

Yes, no additional details given

12 15

Agency-wide policy 7 0

Office-specific policy 0 2

Combination of agency and office policy 1 0

No 1 5

In process of developing policy 3 2

c. Does the records management program comply with ISO 15489?

Yes: 4 offices

No: 3 offices

Don’t know: 17 offices

Although federal and state agencies are not required to comply with ISO

15489, attempted compliance may indicate a dedication to records

management. The option “Don’t Know” was provided to measure whether or

not offices are aware of the international standard in order to discover

cognizance of large-scale records management efforts. Most office employees

are not aware of ISO 15489 but did inquire about the standard or requested

that the research team send them more information.

d. Do program workers receive scheduled training with respect to their

responsibilities for records management?

14

This is defined as a formal program which provides regularly scheduled

training with respect to employees’ responsibilities for records management or

introductory training with refresher courses.

Yes: 14 agencies

Through agency-wide policy or procedure: 1 agency

No: 5 agencies

Intermittent training – not regular: 4 agencies

e. Does the records management staff include an IT expert?

A yes answer is defined as a member of the records management staff who is

an IT expert. IT support staff available for consultation by the records staff

are identified as “outside support” but are not considered records management

staff.

Yes: 8 agencies

No: 8 agencies

IT support provided from outside department: 8 agencies

f. Is there is a formal system for records hold orders relative to claims or

litigation?

See below, section g.

g. Are electronic records included in a formal system for records hold order

relative to claims or litigation?

See table below.

Table 2: Hold Orders

Formal system

for hold orders

Includes

electronic records

Yes

11 8

Agency-wide policy 1 1

No 6

In process of developing policy 2 2

Not Applicable 3 4

Don't know 0 1

Support provided from outside department 1 0

h. Is there a disaster recovery plan for vital records?

This is defined as policies, procedures, and information that direct the

appropriate actions to recover from and mitigate the impact of a catastrophe

(SAA Glossary) on records.

15

Yes: 11 agencies

Agency-wide policy: 2 agencies

No: 3 agencies

In process of developing policy: 4 agencies

Don’t know: 1 agency

Part of Continuity of Operations (COOP): 3 agencies

i. Are there disposition and retention schedules?

All 24 agencies have a written retention schedule providing instructions for

the disposition of records throughout their lifecycle. One agency described

their schedule as being an agency-wide policy, and one agency explained they

have a schedule, but are not currently following it.

j. Are records transferred to storage facilities for inactive storage?

Defined as a transfer before disposition.

See below. Yes: 15, No: 8, N/A: 1

k. Are permanent records identified and preserved or transferred to an

archives?

Yes: 22, No: 1, N/A: 1

Yes No

N/

A

Yes No

N/

A

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Inactive storage

transferred to

archives

Storage and Archiving

Figure 7: Storage and Archiving

Question 17. Has the records liaison or any program worker received any records

management training or services from NARA?

16

a. If yes, how useful was it to you in helping in your electronic records

management efforts?

1) Useful in day-to-day operational records keeping

2) Useful in planning intermediate records-keeping planning (1-2

years)

3) Useful in long-term planning efforts (3-5 years)

4) None of the above, please explain.

This question defined training from NARA as being specific to records

management. 13 out of 24 agencies expressed having received records

management training and/or services from NARA.

NARATr ai ni ng

Yes, 13

No, 9

N/A, 2

Figure 8: NARA Training

Of these 13 “yes” answers, responses were further broken down to explain how

helpful the training was for the electronic records efforts. An “All” answer means

the respondent indicated that NARA training and services were useful in day-to-

day, intermediate, and long-term planning. A “None” answer means the

respondent indicated that NARA training and services were not useful or that they

did not address electronic records. An “Other” answer means the respondent

indicated that NARA training and services were useful in other ways like

Networking and General Records Management rather than for electronic record

management efforts.

How was NARA Training Useful for ERM?

all (3), 3

none, 5

other: networking, 1

intermediate, 1

long-term, 3

other:

general RM, 1

Figure 9: Usefulness of Training (n=13)

17

Question 18. Has your organization received any “targeted assistance” from NARA on

the design and/or implementation electronic record management projects?

a. If yes, in what form?

1) Training

2) Applications Software recommendation

3) Compliance to NARA standards

4) Other (please describe)

b. If yes, approximately how many projects?

1) Please list projects? (Use a separate sheet of paper if necessary)

Only three offices reported receiving targeted assistance from NARA for ERM

projects. This assistance came in the form of system design, specific ERM needs,

and scheduling electronic records. 13 agencies stated they had not received

targeted assistance, two agencies did not know, two had received assistance from

NARA in the form of a project other than electronic records management and for

four agencies, this question was not applicable.

Question 19. What accountability and enforcement mechanisms are in place for records

management (Select all that apply):

a. The records manager conducts scheduled evaluations of program workers’

compliance with records management policies and procedures

b. Program workers are given a certificate or other form of reward when they

receive an excellent evaluation

c. The Inspector General conducts scheduled audits of records management

policies and procedures

d. None of the above. Please explain:

The majority of offices interviewed did not have accountability or enforcement

mechanisms in place for records management. A few were considering

conducting evaluations and providing rewards for excellent records management,

but only five agencies currently offer rewards to employees and have scheduled

audits by the Inspector General. Nine agencies currently conduct scheduled

evaluations of compliance.

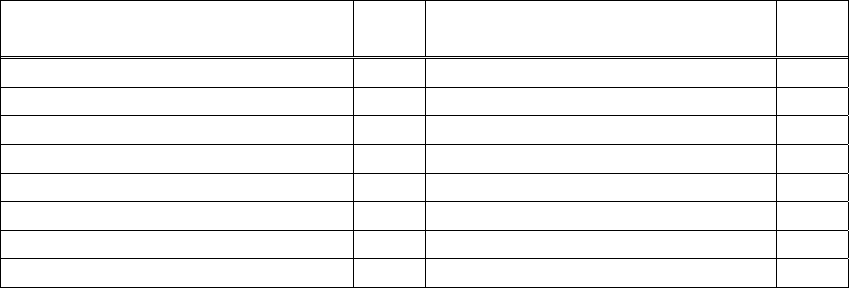

Accountability & Enforcement

9

55

10

15

17

1

3

2

2

1

2

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

evaluations rewards IG

yes informal no no-considering don't know

Figure 10: Accountability & Enforcement

18

Question 20. Is there a clear connection between the records management program and

the overall mission of the agency?

The overwhelming majority (20 out of 24) agencies stated there was a clear connection

between the records management program and the overall mission of the agency (two

agencies said there was not a clear connection, and two agencies did not know), but when

asked to describe the specific elements that described the degree to which the program

was linked with agency mission the responses were not as clear, which complicates the

analysis of the results of this question (see Question 21 “a,” “b,” and “c” results below).

It seems evident that though office representatives may think there is a clear connection

between the records management program and the overall agency mission, when

questioned about specifics, the results indicate the link is not as strong as anticipated.

Question 21. If there is a connection between the records management program and the

agency mission, please describe the degree to which the program is linked with the

overall goals. (Select all that apply)

a. The records management program is included in the annual budget

This is defined as records management as a line item in the annual agency budget.

“Part of other” explains that funding from records management trickles down

from another line item or comes from a different department (for example, IT).

One small agency explained that there was no money for records management

until the agency started implementing an official electronic recordkeeping system.

yes, 12

no, 5

part of other, 4

don't know, 2

N/A, 1

Figure 11: Budget

b. The records manager is a high-ranking official

5

For the purpose of this report, GS 13 and above is considered high-ranking and

GS 11/12 is considered mid-ranking.

5

In general, for the agencies with less than 10,000 employees, this refers to the agency records manager,

and in the larger agencies it refers to the major component (e.g. “service,” “directorate,” or

“administration”) records manager.

19

Rank of Records Manager

low-ranking, 9

N/A, 1

mid-ranking, 4

don't know, 1

high-ranking, 9

0246810

high-ranking

mid-ranking

low-ranking

N/ A

don't know

Figure 12: Rank of Records Manager

c. The records manager is part of IT development teams

IT Development

yes, 11

no, 10

N/A, 1

don't know,

2

Figure 13: IT Development

d. Records management contributes to the annual reporting required by the

Federal Managers Financial Integrity Act of 1982 (FMFIA below).

e. Records management contributes to the annual reporting required by the

Government Performance Results Act of 1993 (GPRA below).

f. Records management contributes to the annual reporting required by the

Information Technology Management Reform Act of 1996 (ITMRA below).

Agency responses to annual reporting required by various government Acts are

listed below. Most agencies were unaware of their contribution to FMFIA and

ITMRA, but many were more familiar with GPRA.

20

Mission Linkage (Acts)

7

10

7

2

4

2

11

6

11

4

4

4

0 5 10 15 20 25

FMFIA

GP RA

ITMRA

yes no don't know N/A

Figure 14: Government Acts

Records Management (22-24)

These questions address how records are currently managed in the office. File plans and

schedules are discussed.

Question 22. Does the office have a file plan?

a. If yes:

1) Is there a copy of the file plan that we could see?

2) For each records series, does the plan reference the relevant item

number in the agency records disposition manual?

b. If no:

1) Can the office tell us which approved items in the disposition

schedule apply to the office’s records?

A file plan is defined as a classification scheme describing different types of files

maintained in an office, how they are identified, where they should be stored, and

how they should be indexed for retrieval. The researchers did not specify that an

office file plan had to include paper and electronic records. However, question 35

b. addressed whether or not paper and electronic records in corporate files are

filed according to the file plan. Questions 37 and 40 also asked whether or not

individual employees follow a file plan when maintaining recordkeeping copies at

their desks and paper copies of e-mails respectively.

21

File Plan

Yes - Office,

4

Yes -

Agency, 3

Yes, 14

No, 3

Figure 15: File Plan

Only three offices stated they did not have a file plan. Of the 21 remaining

offices, seven designated that their file plan was either specific just to their office

or an organization-wide file plan. The researchers reviewed 14 of these 21 file

plans and made some designations about the different elements the file plans

contained and grouped them by similarities and differences.

The file plan elements identified were:

File plan includes a file code or classification number

File plan includes the titles of the records

File plan includes a description of the records

File plan includes the location of the records

File plan includes disposition

Additionally, if the office answered yes to having a file plan, they were asked

whether or not the file plan states the disposition or references the disposition

schedule. If the office answered no to having a file plan, they were also asked if

they could acknowledge which items in the disposition schedule applied to their

records without using a file plan. The results of all of these file plan components

are displayed below.

22

File Plan

0 3 6 9 12 15

Viewed

Includes file code

Includes title

Includes description

Includes location

Includes disposition

References disposition

Original references disposition

No-disposition

yes no N/A

Figure 16: File Plan Specifics

6

Question 23. Does the office use NARA’s General Records Schedules; has the office developed

its own records schedule; or some combination of both?

a. The office uses NARA’s general records schedules for all of its records.

b. The office develops its own records schedules for all records created in the office.

c. The office uses a combination of NARA’s general records schedules and individual

records schedules developed by the office for unique or high-priority records.

The majority of agencies interviewed use a combination of NARA’s General Records

Schedules and individual records schedules developed by the office. The two state

agencies and one private business indicated they use a combination of a

State/Corporate records schedule and individual records schedules developed by the

office.

Records Schedule Used

Unique, 6

Combo, 16

None, 1

GRS, 1

Figure 17: Records Schedule

6

“Original references disposition” = agency policy is that the original document includes disposition

instructions/coding; “No disposition” = neither the file plan nor the original documents referenced

disposition information.

23

Question 24. Does the office use Flexible Scheduling?

a. Never heard of it

b. Heard of it, but not implemented

c. Considering implementation

d. Already implemented

Flexible scheduling is defined as a provision for concrete disposition instructions

that may be applied to groupings of information and/or categories of temporary

records. In other words, it provides instructions for agencies to develop schedules

for disposable program records at as high a level of aggregation as would meet

their business needs. Flexibility is defining record groupings. Flexible

scheduling relates to the “Big Bucket” approach, which refers to the application

of appraisal criteria to multiple, similar, or related groupings of information

across one or multiple agencies to establish a uniform retention period.

Only three agencies surveyed were currently using flexible scheduling for records

management.

Flexible Scheduling

Considering

implementation,

2

Already

implemented, 3

N/A, 4

Heard of it, but

not implemented,

6

Never

heard of it, 9

Figure 18: Flexible Scheduling

24

Paper and Electronic Records Maintenance (25-32)

These questions attempt to discover the physical maintenance of paper and electronic

records. Where they are kept and by whom, duplicates, media, and what constitutes an

official record copy are discussed here.

Question 25. How are records maintained?

a. Exclusively in paper format

b. Exclusively in electronic format

c. Some paper and some electronic

This question posed some problems for the researchers. All 24 respondents

actually maintain a combination of paper and electronic records. Three of these

24 though, stated that they only maintain paper records when in actuality, they

maintain both. Even offices with paper recordkeeping copies keep electronic

duplicates on a shared drive. A mix of paper and electronic formats is common.

The paper records mentioned by the three agencies surfaced later in the survey as

those considered to be the official recordkeeping copy. If an interviewee

answered that they maintain records exclusively in paper format because their

official recordkeeping copy is in paper, but stated they kept duplicates on the

shared drive, the interviewers changed their answer to “records are maintained in

paper and electronic format.”

Question 26. Are paper records copied to another medium (digital, microform, etc.)?

a. If yes:

1) What medium?

2) Does your office retain the paper originals?

3) If yes, are such records integrated with “born-digital” records in an

electronic recordkeeping system?

4) What disposition (or retention) actions are taken for the digitized

records?

Combined with Question 27, see below.

Question 27. Are electronic records copied to another medium?

a. If yes:

1) What medium?

2) Does your office retain the electronic originals?

Answers to questions 26 and 27 were combined due to the similarity of issues

they covered. Offices were asked if they copy paper or electronic records to

another medium and if they retain the original format. Most offices made copies

of both paper and electronic records and maintained the original format. This

comparison was important to discover the presence of duplicate record copies and

redundant systems of recordkeeping. For example, if an office is creating records

in electronic format and printing the electronic version to a paper format and

keeping both the electronic and paper copies, they have two copies of the same

25

record. This dual recordkeeping system (regardless of which copy is official) is a

burden when only one copy requires retention.

0 5 10 15 20 25

make paper copies from e-original

make e-copis from paper originals

yes - keep paper originals

yes - keep electronic originals

Paper and Electronic Copies

yes no NA depends

Figure 19: Paper and Electronic Copies

When asked what type of medium the records were copied to, respondents gave

multiple answers and explained they used more than just one method for copying

records. The answers are displayed in the table below.

For paper records copied to another medium, non-self-explanatory definitions are

as follows:

Digital-typed – information from paper is typed into a digital format (i.e.

database)

Digital-scanned – scanned into a digital format and may be stored on a

server or on removable media

For electronic records copied to another medium, removable media was

sometimes defined by the specific type of removable media (i.e. CD, DVD, or

backup tape) and was sometimes only identified as removable media without

specification.

Again this is significant as it displays the prevalence of dual recordkeeping

systems when it is only necessary to retain one record copy.

26

Table 3: Media Used

Paper records are copied to the

following medium:

Electronic records are copied to

the following medium:

Digital typed 1 Printed to paper 21

Digital scanned 16 Removable media 1

CD 1 Removable media - CD 8

Microform 3 Removable media – backup tape 5

Not Applicable 7 Digital 1

Removable media - DVD 2

Zip disk 1

Not Applicable 2

For paper records copied to another medium, interviewees were asked if these