Cross-Cultural Industrial Organizational Psychology and Organizational

Behavior: A Hundred-Year Journey

Michele J. Gelfand

University of Maryland, College Park

Zeynep Aycan

Koç University

Miriam Erez

Technion - Israel Institute of Technology

Kwok Leung

Chinese University of Hong Kong

In celebration of the anniversary of the Journal of Applied Psychology (JAP), we take a hundred-

year journey to examine how the science of cross-cultural industrial/organizational psychology and

organizational behavior (CCIO/OB) has evolved, both in JAP and in the larger field. We review

broad trends and provide illustrative examples in the theoretical, methodological, and analytic

advances in CCIO/OB during 4 main periods: the early years (1917–1949), the middle 20th century

(1950 –1979), the later 20th century (1980 –2000), and the 21st century (2000 to the present). Within

each period, we discuss key historical and societal events that influenced the development of the

science of CCIO/OB, major trends in research on CCIO/OB in the field in general and JAP in

particular, and important milestones and breakthroughs achieved. We highlight pitfalls in research

on CCIO/OB and opportunities for growth. We conclude with recommendations for the next 100

years of CC IO/OB research in JAP and beyond.

Keywords: cross-cultural, industrial-organizational, organizational behavior

Supplemental materials: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000186.supp

Cross-cultural industrial and organizational psychology

and organizational behavior (CCIO/OB) has a long past and a

short history. Although many of the theories of work behavior

have been developed in the last 100 years, starting with the

launching of the Journal of Applied Psychology (JAP) in 1917,

questions of how to best manage behavior in organizations were

discussed around the globe for centuries prior to the formaliza-

tion of the field. For example, effective selection procedures

were featured in the Old Testament, in which God advised

Gideon on whom to choose for battle (Judges 7:4 New Revised

Standard Version), and the first systematic employee selection

system (i.e., the “imperial examination”) was developed in

China as early as the Han Dynasty. Likewise, in The Republic,

Plato discussed person–job fit, advocating that the ideal job was

one in which the person’s nature is “fitted for the task” (Plato

& Jowett, 1901, p. 56, cited in Antonakis, 2011). Lay theories

of group processes and leadership can also be found in the Bible

and other ancient texts, and advice on persuasion and influence

figures prominently in Sun Tzu’s Art of War (Tzu, 1963). It is

clear that the quest to understand work behavior has been a

global concern since antiquity.

In celebration of the anniversary of JAP, we take a hundred-

year journey to examine how the science of CCIO/OB has

evolved, both in JAP and in the larger field. Our review is

selective by necessity. We review broad trends and provide

illustrative examples in the theoretical, methodological, and

analytic advances in CCIO/OB during four main periods: the

early years (1917–1949), the middle 20th century (1950–1979),

the later 20th century (1980 –2000), and the 21st century (2000

to present). Within each period, we discuss key historical

and societal events that influenced the development of the

science of CCIO/OB, major trends in research on CCIO/OB in

the field in general, and JAP in particular, and important

milestones and breakthroughs. To track the evolution of the

field, we coded all articles in JAP during the period of 1917 to

2014 that focused explicitly on culture and organizational

phenomena, and we traced the evolution of the field of

This article was published Online First February 16, 2017.

Michele J. Gelfand, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland,

College Park; Zeynep Aycan, Department of Psychology and Department

of Business Administration, Koç University; Miriam Erez, Faculty of

Industrial Engineering & Management, Technion - Israel Institute of Tech-

nology; Kwok Leung, Department of Management, Chinese University of

Hong Kong.

This article is dedicated to our dear friend and colleague Kwok Leung,

who passed away during the writing of this article. The authors thank

Joshua C. Jackson, Christina Fahmi, and Nava Caluori for their help in this

review.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Michele

J. Gelfand, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, Bio-

Psychology Building, College Park, MD 20742. E-mail: mjgelfand@gmail

.com

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Journal of Applied Psychology © 2017 American Psychological Association

2017, Vol. 102, No. 3, 514–529 0021-9010/17/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/apl0000186

514

CCIO/OB in JAP on the following criteria: content of the

research (e.g., selection, training, attitudes, personality, intelli-

gence, conflict, teams, and leadership, among others); method-

ology (e.g., laboratory, field); whether aspects of culture (e.g.,

values, norms) were empirically assessed; whether measure-

ment equivalence was assessed; whether culture was examined

as a main effect or if was considered as a moderator (e.g.,

interacts with other contextual factors or individual differ-

ences); and whether the research focused on intracultural or

intercultural comparisons.

1

Early Years: 1917–1949

The discipline of I/O psychology began to develop during the

late 1800s and early 1900s in Europe and the United States. During

this era, Taylor’s (1914) principles of scientific management were

influential amid rapid industrialization and mass manufacturing,

and the zeitgeist was marked by a quest for the discovery of

general principles that were applicable across situations and peo-

ple. The United States had seen a large influx of immigrants from

different countries since the beginning of the 20th century, but the

rise in cultural diversity had not yet drawn attention to the impor-

tance of studying cultural influences on organizational phenome-

non. This was, in large part, because of a focus on minimizing

cultural differences. Indeed, Frost (1920) advocated that a major

contribution of industrial psychologists was the “Americanization

of the alien,” that is, the assimilation of individuals from different

nations, with different attitudes, values, and behaviors, into U.S.

organizations. This view was consistent with the melting pot view

of culture prominent in the United States. In Europe, William

Wundt and his students conducted some of the first research

related to I/O psychology. However, these early studies did not

examine how culture affects work behavior, and it was only in his

later publication of Völkerpsychologie that Wundt (1906) advo-

cated that culture plays a critical role in understanding human

mind and behavior (Araujo, 2013). Yet despite Wundt’s efforts,

this work did not have much influence on psychological research

during his lifetime, and did not lead to a focus on culture in IO/OB.

Later during this period, World War I (1914–1918) precipitated

the need to screen recruits for various military roles, causing

individual differences such as intelligence to figure prominently in

this period’s research (Vinchur & Koppes, 2011). In the United

States, testing and selection researchers working for the Army

were aware of the influence of culture, but the focus was on

creating a selection test for those with lower English-language

skills (the Army Beta). In World War II (1939 –1945), even more

attention was given to the selection and placement of soldiers, but

culture was still ignored (Katzell & Austin, 1992). In one excep-

tion, Stouffer and his colleagues studied American soldiers in

World War II and analyzed the perception of relative deprivation

among soldiers of different ethnicities (Stouffer, Suchman, DeVin-

ney, Star, & Williams, 1949). This study provided an important

conceptual basis for the development of equity theory, a major

theory in I/O psychology (Adams, 1965). It is fair to conclude that

I/O psychology in the very early years in the United States re-

mained largely culture bound, that is, theories were tested only on

American samples, and culture blind, that is, culture was not

considered as an important factor (Katzell & Austin, 1992).

Several other notable events occurred during this period that

warrant discussion. In his cultural analysis of economic systems,

Max Weber (1905/1958) discussed the Protestant work ethic and

the rise of capitalism in Europe, which was a pioneering attempt to

relate culture from the perspective of religion to economic activ-

ities. Weber also studied religions in China and India, and con-

cluded that, unlike Protestantism, these religions were not condu-

cive to capitalism. This work later inspired a program of research

on the Protestant work ethic in I/O psychology (e.g., Merrens &

Garrett, 1975) and cross-cultural psychology (e.g., Sanchez-Burks,

2002). Other significant events during this time period were the

1919 founding of the International Association of Applied Psy-

chology (IAAP), which, to date, has been an international meeting

ground for organizational scholars worldwide, as well as the es-

tablishment of American Psychological Association’s (APA’s)

Committee on International Relations in Psychology in 1944.

In sum, I/O psychology in the very early years did not pay much

attention to the influence of culture. Despite Wundt’s Volkerpsy-

chologie and Weber’s comparative analysis of different economic

systems, JAP only featured sporadic papers on ethnic differences

(e.g., Garth, Serafini, & Dutton, 1925; Sánchez, 1934), and these

papers were largely descriptive in nature.

Middle 20th Century (1950-1979)

During this period, several significant theoretical, empirical, and

institutional developments occurred in the field of CCIO/OB and

cross-cultural psychology more generally. Against the backdrop of

mainstream psychology’s focus on universal laws of human be-

havior, a critical mass of scholars began to demonstrate wide

variability in psychological processes across cultural groups. The

1950s and 1960s witnessed many seminal studies on culture and

personality (B. B. Whiting & J. W. Whiting, 1975; J. W. Whiting

& Child, 1953), perception (Segall, Campbell, & Herskovits,

1966), motivation (McClelland, 1961), cognition (Witkin & Berry,

1975), and mental abilities (Cronbach & Drenth, 1972) that later

became the bedrock of much of modern day CCIO/OB. The fact

that even “basic” psychological processes were not universal (e.g.,

visual illusions; Segall et al., 1966) was a wakeup call and opened

up the field to the possibility that organizational phenomena might

also be subject to wide cultural variability. This period also wit-

nessed the explication of individualism-collectivism as an impor-

tant dimension of culture (Triandis, 1972), and the notion that

cultural differences can arise as adaptations to ecology (e.g., the

eco-cultural approach; Berry, 1975; Triandis, 1972). During this

time period, we also witnessed significant institutional develop-

ments, including the formation of the International Association for

Cross-Cultural Psychology and the launching of major journals

1

Our review included cross-cultural comparisons (comparison of two or

more cultural groups across nations), intercultural interactions (examina-

tion of two or more groups from different nations who interact with each

other or interactions of ethnically diverse individuals within the same

nation), within-country comparisons across groups (e.g., Asian Americans

vs. Caucasians in the United States), and tests of the generalizability of a

theory typically developed in the U.S. within another nation (e.g., exami-

nation of a Western theory in another country). We also separately coded

the number of articles that were conducted outside of the United States that

were not explicitly focused on culture per se to illustrate how culturally

diverse the populations are in JAP across the last 100 years.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

515

CROSS-CULTURAL I/O/OB

(e.g., International Journal of Psychology, Journal of Cross-

Cultural Psychology).

There were also a number of important scholarly works pub-

lished during this period within CCIO/OB. Harbison and Myers’s

(1959) Management in the Industrial World presented a large-

scale study of comparative management, and Haire, Ghiselli, and

Porter’s (1966) Managerial Thinking compared managers across

14 countries (see also Stouffer et al., 1949). There were also

several reviews of cross-cultural research in IO/OB during this

time period (Barrett & Bass, 1970; Boddewyn & Nath, 1970;

Roberts, 1970).

In a chapter in the Handbook of I/O Psychology, Barrett and

Bass (1970) nevertheless lamented that culture was largely ignored

in mainstream organizational psychology, and argued that

most research in industrial and organizational psychology is done

within one cultural context. This context puts constraints upon both

our theories and our practical solutions to the organizational problems.

Since we are seldom faced with a range and variation of our variables

which adequately reflect the possibilities of human behavior, we tend

to take a limited view of the field. (p. 1675)

These observations on the state of the science of CCIO/OB were

largely borne out in our review of articles published in JAP during

this period. There were few papers in JAP during this period that

focused on culture (see Figure 1), and the majority of papers

appearing in this period did not advance any theory on expected

cultural differences or similarities. Some articles focused on ex-

amining reliability of established measures in different countries

(e.g., achievement motivation: Gough & Hall, 1964; personnel

inventories: Raubenheimer, 1970; and leadership: Tscheulin,

1973). Others focused on testing whether I/O theories replicated in

other countries, though the discussion of culture was largely post

hoc. For example, research tested the generalizability of Hertz-

berg’s two-factor theory (Hines, 1973), Fiedler’s theory of least

preferred coworker (Bennett, 1977), and Vroom’s expectancy the-

ory of motivation (Matsui & Terai, 1975). Several JAP articles

during this period did begin to investigate differences in manage-

rial beliefs and values across countries. Notably, Hofstede (1976)

published a paper in JAP on values of managers from 40 nation-

alities, which were organized into five clusters (Nordic, Germanic,

Anglo, Latin, and Asian), and Lonner and Adams (1972) described

vocational interests across nine nations. Others explicitly stated a

need to recruit cross-cultural samples to expand the focus of I/O

psychological research. For example, Zurcher (1968) discussed

particularism as an important value in Mexico, and Triandis and

Vassiliou (1972) discussed the role of group orientation (later to be

called “collectivism”) as a predictor of selection decisions in the

United States and Greece.

Much work during this period focused on cross-cultural com-

parisons (e.g., comparisons of two or more cultural groups across

nations; see Figure 2), though there was a line of research on

cross-cultural adaptation, which focused on the development of

specific training interventions to assist employees working in Iran,

Thailand, Central America, and Greece (Fiedler, Mitchell, & Tri-

andis, 1971; Worchel & Mitchell, 1972). Culture was largely

equated with country, and the focus was on main effects of culture

(e.g., Shapira & Bass, 1975; Slocum & Strawser, 1972; Whitehall,

1964; Zurcher, 1968). Very few studies discussed translation pro-

cedures or performed tests of equivalence for their measures.

There was a dearth of theorizing on what explains cultural varia-

tion, though one paper focused on the role of economic develop-

ment in understanding cultural differences in conflict behavior

(e.g., Porat, 1970), and most studies were of a correlational nature

(see Figures 3a to d). In all, research on CCIO/OB began to

increase in Journal of Applied Psychology (JAP) during this pe-

riod, but with few exceptions, research on culture was still largely

theoretical, with little attention to methodological issues that need

to be accounted for in doing cross-cultural research.

Later 20th Century: 1980s-2000

A number of significant changes in the world influenced the

growing awareness of cross-cultural differences in the final de-

cades of the 20th century: the invention of the World Wide Web

(1989), the spread of home computers, the fall of the Berlin Wall

(1989), the opening of relations between China and the West, and

the accelerating process of globalization. These technological and

geopolitical changes resulted in individuals and organizations hav-

ing much more exposure and interaction with people from differ-

ent cultures. Globalization also accelerated worldwide industrial

competition during this period, which attracted researchers’ atten-

tion to studying cultural similarities and differences in quality

circles and teamwork (Erez & Earley, 1993).

During this period, a number of scholarly works on culture were

published, which significantly affected the development of CCIO/

OB. Hofstede’s (1980) seminal book, Culture’s Consequences, of-

fered a typology of cultural values, including individualism-

collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity-

femininity, which enabled comparisons of values among cultures (see

also later work on Confucian Dynamism by Hofstede & Bond, 1988).

Schwartz (1992) published his circumplex of cultural values, which

offered a theoretical taxonomy for understanding value compatibili-

ties and value conflicts. During this era, reviews of culture and

organizations were published in the Handbook of Cross-Cultural

Psychology (Tannenbaum, 1980) and in JAP (Bhagat & McQuaid,

1982). Notably, an entire volume on methods in cross-cultural re-

search appeared in the Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology,

which provided systematic advice on translations, experiments, sur-

veys, and ethics, among other topics. Van de Vijver and Leung (1997)

provided detailed suggestions on how to establish equivalence of

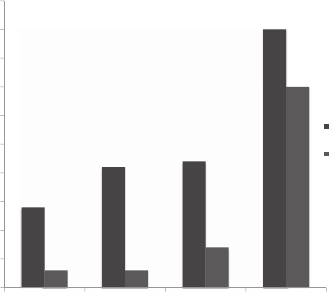

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

1920-1950 1950-1980 1980-2000 2000-present

Focus on culture

No focus on culture, but non-

USA sample

Figure 1. Growth of cross-cultural research over time.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

516

GELFAND, AYCAN, EREZ, AND LEUNG

measurement and deal with response bias, and discussions of levels of

analysis in cross-cultural research began to appear (Leung, 1989). An

entire volume on cross-cultural I/O psychology, edited by Triandis,

Dunnette, and Hough, was published as Volume 4 of the 1994

Handbook of Industrial Organizational Psychology, and a special

volume, New Perspectives on International Industrial/Organizational

Psychology (Earley & Erez, 1997), appeared as part of the Society for

Industrial and Organizational Psychology book series. The APA also

established Division 52 (International Psychology) during this time

period.

Another important theoretical development in CCIO during this

time period was the publication of Erez and Earley’s (1993)

seminal book entitled Culture, Self-Identity, and Work. Drawing

on other work on culture and self (Markus & Kitayama, 1991;

Triandis, 1989), the authors proposed that culture shapes a per-

son’s self through the process of socialization, and this culture-

based self serves as a basis for evaluating the implication of

different organizational practices for a person’s self-worth and

well-being. It had broad-ranging implications for understanding

why certain organizational practices (e.g., motivational practices,

human resources [HR] practices and work design) would be more

or less motivating depending on the cultural context. This notion of

culture fit was also integrated into a theory of HR practices and

individual motivation during this period (Aycan et al., 2000).

Amid this increasing activity, the volume of papers involving

culture was still relatively low in JAP (see Figure 1). Across all of

these articles, there were several notable trends. First, researchers

began to sample a broader array of geographical regions, though

the authors of these studies were largely from the United States

and other Western countries. Research during this period, much

like the previous period, was largely focused on cross-cultural

comparisons (42%) and testing the generalizability of theories

across countries (38%; see Figure 2). Most of these studies con-

cluded that although some of these theories could be generalized to

other cultures, many needed important modifications. For exam-

ple, an examination of Meyer and Allen’s (1991) three-component

model of organizational commitment did not fully replicate in

South Korea (Ko, Price, & Mueller, 1997). Cross-cultural differ-

ences were also evident in the meaning of organization citizenship

behavior (OCB), with employees from Hong Kong and Japan

regarding some categories of OCB as an expected part of the job,

unlike participants from the United States and Australia, who

considered OCB to be independent of the job requirements (Lam,

Hui, & Law, 1999). Likewise, a test of the goal-setting theory of

motivation in the United States and in Israel demonstrated that

Americans reached similar levels of performance under participa-

tive and assigned goals, yet Israelis performed significantly lower

under assigned than participative goals. The authors argued this

reflected Israelis’ low level of power distance (Erez & Earley,

1987). In the field of leadership, the two-factor structure of lead-

ership behavior (e.g., consideration and initiating structure), which

had repeatedly been found in Euro-American samples, was not

supported in Iran (Ayman & Chemers, 1983). In the field of

conflict, Tinsley (1998) expanded the focus of interest models of

disputing to include status and regulation models, which were

particularly relevant in Japan and Germany, respectively.

Very few studies measured aspects of culture (Figure 3a), and of

all of the CCI/OOB papers published in JAP in the 1980s and

1990s, only three tested for measurement equivalence (e.g., Ghor-

pade, Hattrup, & Lackritz, 1999; te Nijenhuis & van der Flier,

31%

69%

1920 - 1950

71%

10%

19%

1950 - 1980

Cross-cultural

Intercultural

Both cross-cultural

and intercultural

Within-country

comparison

across groups

Wthi

i

n-country

Ge

neralizability of a

theory

42%

8%

12%

38%

1980 - 2000

50%

27%

5%

3%

15%

2000 - present

Figure 2. Percentage of different types of culture studies. Cross-cultural comparisons involved a comparison

of two or more cultural groups across nations; intercultural studies involved an examination of two or more

groups from different nations who interacted with each other or interactions of ethnically diverse individuals

within the same nation; within-country comparisons across groups were investigations of group differences with

a particular nation (e.g., Asian Americans versus Caucasians in the United States); within-country test of the

generalizability of a Western theory in another country.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

517

CROSS-CULTURAL I/O/OB

1997; Zeidner, 1987). Most JAP studies in this period focused on

culture as a main effect similar to the previous period (Figure 3b),

with a few exceptions. Gelfand and Realo (1999) showed that

accountability (as a norm enforcement mechanism) can produce

opposite effects in individualistic and collectivistic samples, and

Erez and Earley (1987) demonstrated that culture moderated the

effect of goal setting on performance. The importance of studying

culture in context was also beginning to feature in other psychol-

ogy journals as well (Aycan, Kanungo, & Sinha, 1999; Earley,

1993).

Other notable trends in JAP are shown in the figures. Supple-

mental Figure 1 of the online supplemental materials shows that

the topics of interest started to diversify considerably compared

with the previous period. During this time period, there were also

a few studies that included concepts from other cultures that were

not discussed in the mainstream IO and OB literature. For exam-

ple, a comparison of perceived fairness in selection procedures

revealed that graphology was more positively perceived in France

than in the United States (Steiner & Gilliland, 1996). During this

time period, the methods and samples used to study CCIO/OB also

began to diversify (see Figures 3b and 3d).

Emerging Sophistication: The 21st Century

(2000 to Present)

As with other periods, several notable societal and scientific

events have affected the evolution of CCIO/OB over the last 15

years. The aging workforce, especially in Western developed

economies, has dramatically increased the demand to attract and

retain talent from diverse cultural backgrounds (Burke & Ng,

2006). However, human crises, especially the terrorist attacks of

September 11, 2001, also brought forth a hesitancy to embrace

cultural diversity (Burke & Ng, 2006). After this traumatic event,

human resource management (HRM) practices in organizations in

the United States were found to be more conservative and discrim-

inatory, which has likely challenged efforts to understand and

manage cultural diversity in organizations (e.g., Morgan, 2004).

Another important global trend in this era is the increasing

emphasis on cultural diversity in universities, and particularly in

MBA curricula, in which the introduction of MOOCs (massive

open online courses) provided incredible momentum to the inter-

nationalization of higher education in the world. Additionally,

university ranking systems now include “internationalization” as

an important criterion to evaluate universities in the world

(Stromquist, 2007). In response to this trend, several special issues

are published on how to teach cross-cultural management effec-

tively in business schools (e.g., Eisenberg, Härtel, & Stahl, 2013).

The quantum increase in the use of the Internet and social media

has not only connected culturally diverse populations but also

procured “big data,” which are available to be analyzed by cross-

cultural researchers (see Bail, 2014; Castells, 2004). Furthermore,

global, longitudinal, and open-access data sets began to capture

societal values and practices, including the International Social

Survey Programme (http://www.issp.org/index.php) and the

World Values Survey (http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs

.jsp). Within this context, the debate on whether or not cultures

converge or diverge in the face of globalization continued with

0

20

40

60

80

100

1920 -

1950

1950 -

1980

1980 -

2000

2000 -

present

b. Design Percentage Breakdown of

Studies about Culture

Experiment

Correlational Lab

Study

Meta-analysis

Field Experiment

Correlational Field

Study

Theory or Review

paper

0

20

40

60

80

100

1920 -

1950

1950 -

1980

1980 -

2000

2000 -

present

d. Percentage Breakdown of Culture

Studies’ Populations

Employee

Student

Other

0

10

20

30

40

50

1920 - 19501950 - 19801980 - 2000 2000 -

present

a. Percentage of Cultural Studies

that Measure Culture

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1920 -

1950

1950 -

1980

1980 -

2000

2000 -

present

c. Percent of Main Effect vs.

Moderated Effect Studies

Main Effect

Moderation

Figure 3. Characteristics of articles about culture.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

518

GELFAND, AYCAN, EREZ, AND LEUNG

great force. Two key publications stirred the debate: One argued

that globalization is making the world “flat” (Friedman, 2005), and

the other argued against globalization producing homogeneity

(Klein, 2002). Project GLOBE, which showed that cultural differ-

ences in values and practices continue to persist, provided support

for the latter perspective (Chhokar, Brodbeck, & House, 2008;

House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004).

Along with these societal developments, there have been nu-

merous theoretical advancements in the field. Most notably, there

is a growing recognition that “country” may not be the most

appropriate unit of analysis for cross-cultural research (Fischer,

2009; Minkov & Hofstede, 2014; Taras, Steel, & Kirkman, 2016),

and that cross-cultural variability can be captured at the state,

ethnic/racial, religious, or socioeconomic status (SES) levels

within countries (e.g., Dheer, Lenartowicz, Peterson, & Petrescu,

2014; Greenfield, 2014; Harrington & Gelfand, 2014; Markus &

Conner, 2014; Yamawaki, 2012). Relatedly, there is a shift from

static to dynamic views of culture. Developments in the cognitive

sciences have stimulated the view of culture as a loose network of

multiple, and sometimes conflicting, knowledge structures that can

be activated (or suppressed) depending on the demands of the

situation. This view is contrasted with a conception of culture as a

set of stable structures (e.g., value orientations) and has produced

research on cultural frame shifting, wherein individuals can dy-

namically integrate and dissociate from elements of their culture

(e.g., Benet-Martínez, Leu, Lee, & Morris, 2002; Hong, Morris,

Chiu, & Benet-Martínez, 2000; Shore, 1996). The constructs of

cultural intelligence and global identity were also advanced to help

explain adaptation to the global work context (Arnett, 2000; Erez

et al., 2013; Lisak & Erez, 2015; Rockstuhl, Seiler, Ang, Van

Dyne, & Annen, 2011).

This era has also witnessed extensions of the value frameworks

predominantly used in CCIO/OB and cross-cultural psychology

more generally (see the special issue of the Journal of Interna-

tional Business Studies edited by Devinney, Kirkman, Caprar, &

Caligiuri, (2015); see also Tung & Verbeke, 2010). Scholars began

to broaden the scope of cultural difference variables to include

beliefs (e.g., social axioms: Leung & Bond, 2004) and norms (e.g.,

tightness-looseness: Chiu, Gelfand, Yamagishi, Shteynberg, &

Wan, 2010; Gelfand, Nishii, & Raver, 2006; Gelfand et al., 2011).

There have also been calls for deeper and fine-grained understand-

ing of the construct of individualism and collectivism (e.g., Yam-

agishi, 2011). Interestingly, during this period, there has been a

return to the 1960s and 1970s focus of understanding the ecolog-

ical and historical bases of culture (Berry, 1975; Triandis, 1972),

such as climate and subsistence systems (e.g., Van de Vliert,

2013), societal threat (Gelfand et al., 2011), and even genetic

characteristics of populations (e.g., Minkov, Blagoev, & Bond,

2015).

Research has moved beyond main effects to examine complex

Culture

⫻ Context interactions (Aycan, 2005; Gelfand et al., 2013;

Nouri et al., 2013, 2015), and research has increasingly examined

intercultural interactions. Examples include research on multicul-

tural colocated and virtual teams (Erez et al., 2013; Hülsheger,

Anderson, & Salgado, 2009; Stahl, Maznevski, Voigt, & Jonsen,

2010), expatriate or global managers (Shaffer, Harrison, Gregersen,

Black, & Ferzandi, 2006; Stahl & Caligiuri, 2005), and computer-

mediated cross-cultural interactions (Vignovic & Thompson, 2010).

Recent methodological developments have also allowed cross-

cultural research to broaden its scope. Online surveys using panel

data (e.g., MTurk, Qualtrics) have made data collection from many

countries easy, though these platforms are not without limitations

(Mason & Suri, 2012). Researchers are more frequently testing

measurement invariance or equivalence (Chen, 2008), and are

increasingly using numerous data analytical strategies (e.g., mod-

erated meditational analyses, multilevel models, nested hierarchi-

cal clustering to reveal cultural clusters; M. W.-L. Cheung, Leung,

& Au, 2006; Ronen & Shenkar, 2013). Research has employed

creative methodologies, such as Google Ngram viewer, to trace

changes in cultural values (Greenfield, 2013).

This growing theoretical and methodological sophistication of

the study of culture can clearly be seen in the evolution of this

work in JAP over the last 15 years. There has been a rapid increase

in the number of papers that focus on culture in the journal, and an

exponential increase in the number of studies that are conducted on

non-U.S. samples that do not have a focus on culture (see Figure

1). The diversity of topics has increased, with topics such as

work–family conflict, counterproductive work behavior (sexual

harassment, abusive supervision, mistreatment), psychological

contracts, stress, and turnover adapting a cross-cultural lens, and

the first work on culture and emotions (e.g., shame and guilt)

appeared (supplemental Figure 1). Studies of intercultural interac-

tions have also dramatically increased (see Figure 2). Many papers

have begun to measure culture (Figure 3a) and moved beyond

main effects to explore moderators of cultural differences (Figure

3c). The diversity of methods and samples has also increased (see

Figures 3b and 3d).

As with the larger field, JAP has featured increasing theoretical

complexity in the study of culture. Chao and Moon (2005) pro-

posed a new model of culture using the metaphor of a mosaic to

identify demographic, geographical, and associative features to

describe the unique cultural identity of individuals, and Gelfand et

al. (2006) advanced a multilevel theory of cultural tightness-

looseness in organizations. Others advanced the classic work by

Hofstede (1980) to show when values such as individualism-

collectivism will exert stronger or weaker effects. For example, in

their seminal meta-analysis, Taras, Kirkman, and Steel (2010)

found that compared with personality and demographics, cultural

values had stronger associations with organizational attitudes and

weaker associations with performance, absenteeism, and turnover.

They also showed how norms (i.e., tightness) strengthened the

effect of value on organizational outcomes.

Another exciting trend in CCIO/OB has been a focus on under-

standing work behavior through emic (i.e., culture-specific) con-

structs. For example, guanxi (the Chinese concept of the social

relationships that facilitate networking; Huang & Wang, 2011)is

mentioned in 36 articles in the Academy of Management Journal

(AMJ) and in 16 articles in JAP. The Japanese constructs of giri

(the extent to which obligations to roles and duties are fulfilled)

and taimen (the extent to which face is maintained) were also used

to understand cultural differences in conflict (Gelfand et al., 2001).

New dimensions have been added to existing constructs. For

example, Ramesh and Gelfand (2010) expanded the job embed-

dedness model to include family embeddedness—a new construct

salient in the Indian cultural context—to find that it explained

variance in both India and the United States. As they noted, the

study “draws attention to the fact that cross-cultural expansion of

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

519

CROSS-CULTURAL I/O/OB

theory can illuminate factors that are important in all cultures but

might get limited attention” (p. 818; see also Rockstuhl, Dulebohn,

Ang, & Shore, 2012; Wong, Tjosvold, & Yu, 2005).

During this period, articles in JAP have increasingly moved

beyond comparisons across countries to explore complex dynam-

ics in intercultural contexts (e.g., expatriate adjustment, multicul-

tural teams, negotiation). For example, Stahl and Caligiuri (2005)

studied the adaptation processes of Germans in Japan and the

United States, and found that problem-focused rather than emo-

tional coping strategies were more effective, particularly in high

power distance contexts. Other articles compared the dynamics in

multicultural and monocultural dyads and teams (Adair, Okumura,

& Brett, 2001; Liu, Chua, & Stahl, 2010), and the types of leaders

that are best suited for multicultural teams. For example, Lisak and

Erez (2015) found that emergent leaders in multicultural virtual

teams scored higher than other team members on their glocal

identity (high global, high local identity; see also Greer, Homan,

De Hoogh, and Den Hartog [2012], for an exploration of effective

leaders of ethnically diverse teams).

Articles published in JAP during this time period have tested the

generality of a wide range of classic IO/OB theories. These have

included Karasek’s (1979) decision latitude model of work

(Schaubroeck, Lam, & Xie, 2000), Graen and Uhl-Bien’s (1995)

leader-member exchange theory (Rockstuhl et al., 2012), Rous-

seau’s (2000) psychological contract theory (Hui, Lee, & Rous-

seau, 2004), and Fitzgerald, Hulin, and Drasgow’s (1995) theory

of sexual harassment (Wasti, Bergman, Glomb, & Drasgow,

2000). JAP also published several articles on the validity of scales

used in different countries, such as personality inventories and

measures of organizational citizenship, job satisfaction, resistance

to change, and multisource feedback in performance evaluation,

among others (e.g., Liu et al., 2010; Oreg et al., 2008). Several JAP

articles also investigated complex interactions between culture and

context. For example, Gelfand et al. (2013) used moderated me-

diation to show that descriptive norms can explain culture by

context interactions in team and solo negotiations in the United

States and Taiwan (see also Fisher, 2014, for a multilevel exam-

ination of role overload, empowering organizational climate, and

culture).

Finally, we see increasing methodological sophistication of

cross-cultural research published in JAP in this era. Research is

increasingly moving beyond two country comparisons to explore,

in some cases, over 20 countries (i.e., Atwater, Wang, Smither, &

Fleenor, 2009; Peretz & Fried, 2012; Rockstuhl et al., 2012;

Sturman, Shao, & Katz, 2012). Though still low in frequency,

there have been several studies that have adopted a multiple

method approach, which is particularly important in cross-cultural

research (Gelfand, Raver, & Holcombe Ehrhart, 2002). Cultural

differences are increasingly measured rather than assumed, and

attention to translations and measurement equivalence, although

still somewhat low, is gradually increasing.

Summary: 100 Years of Cross-Cultural

Research in JAP

In this hundred-year journey, we witness the evolution of

cross-cultural IO/OB research. Across each historical period,

from the early years to the mid- to late 20th century, to the 21st

century and beyond, we can see how societal and intellectual

events dramatically affected the course of CCIO/OB science.

The motivations for doing cross-cultural research are certainly

diverse, be they testing the generalizability of Western theories;

broadening existing theories; developing new measures and

theories of cultural variation; comparing main, moderating,

and/or multilevel effects across many areas of CCIO/OB; or

examining the nature of intercultural interactions and bicultur-

alism. However, the common denominator across all of these

efforts has been recognizing the existence of cultural diversity

and the desire to understand people’s values, norms, and be-

haviors across cultures. As the world is becoming increasingly

more global, understanding cross-cultural similarities and dif-

ferences will enable us to harness the cultural diversity across

dispersed geographical zones and enhance people’s quality of

life around the globe.

In many ways, the field has increased in its scope, diversity,

and theoretical and methodological sophistication. Collectively,

JAP published 102 papers from 1917 to 2014 that explicitly

considered cultural variation, and an additional 50 papers ap-

peared that included populations beyond the United States that

did not have culture as their focus. Figures 1 through 3 illustrate

that the diversity of samples, topics, and methods in CCIO/OB

are increasing at dramatic rates. These figures also illustrate

that although research published in JAP has generally not

assessed aspects of culture (e.g., values, beliefs, norms) that

potentially explain differences in work behavior, the rate of

their assessment is steadily increasing, as is the assessment of

measurement equivalence. Research is moving beyond main

effects to examine culture as a moderator, and the presence of

multilevel models is increasing in the field in general, and JAP

in particular.

Yet amid the progress noted throughout this discussion it is

important to emphasize that the attention to culture in the

journal is actually remarkably low: Of the 9419 papers pub-

lished in JAP between 1917 and 2014, the proportion of articles

that explicitly focus on culture is only 1% (including nonwest-

ern samples without a specific focus on culture in the analysis

brings the total to 1.6%). Moreover, the scope of CCIO/OB is

still very limited. Research on CCIO/OB sampled from a nar-

row range of countries, most notably Europe (34%), North

America (27%), Asia (24%), Africa (3%), Australia (3%), and

South and Central America (9%). As well, the articles reviewed

in JAP showed a high level of Western dominance: 66% of first

authors were American. This is similar to Tsui, Nifadkar, and

Ou’s (2007) analysis of cross-cultural organizational science in

which they found that 68% of the studies’ first authors were

from the U.S. and remarkably, 100% of the 69 unique first

authors were from countries characterized as having “high

human development” (see Kirkman & Law, 2005, for a review

of trends in international management research in AMJ). This

dominance, though largely unintentional, restricts the potential

of a truly global organizational science in terms of the questions

asked, the constructs developed, and the conclusions reached.

Overall, the immense potential for globalization in the field has

yet to be tapped even despite societal and intellectual trends and

global issues that warrant understanding cultural variation and

universality.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

520

GELFAND, AYCAN, EREZ, AND LEUNG

The Next 100 Years of Cross-Cultural I/O

OB Research

In this final section, we take the opportunity to highlight our

vision for the next 100 years of culture research in IO/OB in

general, and in JAP in particular. As we discuss at length in the

following sections, the field should build on the momentum oc-

curring on numerous theoretical, methodological, and empirical

fronts. In this next 100 years, we need to (a) broaden the questions

we ask in CCIO/OB, (b) give more attention to the conceptualiza-

tion and operationalization of culture, (c) make dynamic perspec-

tives of culture more of the norm than the exception, (d) have an

increased focus on intercultural interactions and the global context

of work, (e) take the meaning of constructs across cultures more

seriously, and (f) increase the methodological and disciplinary

perspectives devoted to the study of culture in IO/OB. Each is

discussed in turn.

Broadening the Questions We Ask in CCIO/OB

Philosophers of science have long argued that science is

value-laden (Kuhn, 1962; Lefkowitz, 2003). As Sampson

(1978) specifically noted, “modern science emerged within a

particular sociohistorical context [in which] the values of lib-

eralism, individualism, capitalism, and male dominance [are]

primary” (p. 1334). Importantly, these values profoundly affect

the questions we find worthy of study as well as those that we

do not (Gelfand, Leslie, & Fehr, 2008).

CCIO/OB research is no exception; it has largely been pio-

neered in the United States and the West, and is laden with

culture-specific values and sociopolitical realities that risk be-

ing exported to other cultures. For example, Gelfand et al.

(2008) noted that theories and research questions in CCIO/OB

largely reflect a cultural model of the independent self, empha-

sizing individual differences, freedom of choice, and the pursuit

of happiness and personal satisfaction, which is made possible

in countries in which there is affluence, industrialization, and

relative social tranquility (Inglehart, 2000). Yet in contrast,

millions of individuals around the globe face daily realities of

poverty, conflict, terrorism, and corruption—where basic needs

and safety concerns loom large—necessitating that different

research questions be asked that are not only vital to individuals

but to societal development. As Gelfand et al. noted, in these

contexts,

the science of job security and unemployment might take precedence

over the science of job satisfaction and commitment; the criteria for

selection systems might focus less on objectivity and validity, and

more on the legitimization of subjectivity and nepotism...thefocus

of training...might be on basic skills such as literacy. (p. 29)

Other Western values permeate our theories and questions asked

in CCIO/OB. For example, Western cultures prioritize bound-

aries (e.g., between work and family, religion and state), yet

such boundaries do not necessarily apply in other cultures. The

influence of religion in the workplace, for example, is rarely

examined in CCIO/OB, yet is likely important in many coun-

tries in the world. In all, we argue that in the next 100 years of

research in CCIO/OB, we need to be mindful that the theories

we develop and questions we ask may be laden with Western

concerns, and we must strive to ask new questions that reflect

other societal values, assumptions, and sociopolitical realities.

Operationalization of Culture Through Measurement

and Attention to Levels of Analysis

The CCIO/OB scholarly community needs to engage in deep,

critical, and multidisciplinary understanding of what culture is

and how it should be best captured. We believe that CCIO/OB

should embrace conceptual diversity when it comes to under-

standing and modeling culture, yet also must be precise regard-

ing the level of theory and measurement being advanced. Gel-

fand et al. (2008) describe various forms of culture that could be

of interest in CCIO/OB, including those at the individual level

(personal values, subjective cultural press), the unit level (ad-

ditive culture, or averages of individual values vs. cultural

descriptive norms, or averages of perceived descriptive norms),

as well as those that reflect dispersion (variance in values or

perceived descriptive norms), all of which might have different

influences on I/O OB phenomena.

Indeed, the recent special issue of the Journal of Interna-

tional Business Studies entitled “What is Culture and How Do

We Measure It?” (Devinney, Kirkman, Caprar, & Caligiuri,

2015) provides additional frameworks for the measurement of

culture, cultural diversity, and cultural distance. For example,

drawing on topology and matrix algebra, Venaik and Midgley

(2015) proposed a methodology called “archetypal analysis” as

an alternative to a value-based approach to measurement of

culture. Archetypes are perfect theoretical representations of

configurations of values shared by a group. The transnational

archetypes identified by the authors cut across different coun-

tries and represent the “etic,” whereas the subnational arche-

types (i.e., unique configurations of value) represent the “emic”

aspect of culture. Hence, this methodology offers a novel way

of reconciling the etic– emic tension. Likewise, building on

methodologies from economics, political science, and ethnog-

raphy, Luiz (2015) proposed an alternative methodology to

assess intranational diversity and cultural distance, which he

referred to as “ethno-linguistic fractionalization.” Future re-

search can use this index to answer such questions as whether

or not expatriates or multinational corporations perform better

in heterogeneous, rather than homogenous, cultures (see also

Mohr & Ghaziani [2014], for advances in sociology to improve

clarity in the conceptualization and operationalization of cul-

ture).

In the next 100 years, the literature also needs to move

beyond studying culture at the national level. National bound-

aries, some of which are admittedly arbitrary, may not always

offer the most appropriate unit of analysis to study culture (see

Fischer, 2009; Taras et al., 2016). As noted, recent research has

discovered cultural differences (i.e., in values and the strength

of norms) across the lines of socioeconomic class, profession,

religion, ethnic groups, age cohorts, and regions within coun-

tries (e.g., Harrington & Gelfand, 2014; Luiz, 2015; Markus &

Conner, 2014; Ronen & Shenkar, 2013; Taras et al., 2010). We

need to develop more complex models that simultaneously

examine how multiple levels of culture—such as global, na-

tional, regional, state, community, industry, organizational, and

team levels—affect behavior in organizations. We also need to

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

521

CROSS-CULTURAL I/O/OB

understand how national culture dynamically interacts with

SES, gender, and age, among other demographic and personal-

ity attributes, to affect work behavior. More generally, with the

advent of multilevel modeling techniques, it is possible to

examine many different models of cultural influence, ranging

from single-level models to cross-level direct and cross-level

moderated models of culture, as well as to model the simulta-

neous influence of different sources of culture on units, teams,

and individuals (e.g., mixed-determinant models; Kozlowski &

Klein, 2000; see also Gelfand et al., 2008).

Dynamic Perspectives of Culture Should Become the

Norm, Not the Exception

Research has clearly shown that culture can be as important

of a predictor of organizational phenomena as other variables

such as demographics and personality traits (Taras et al., 2010).

We believe the time has now come to devote more attention to

the questions of under what conditions and for which type of

criteria do cross-cultural differences matter the most? Taras et

al. (2010), for example, showed that cultural differences may be

moderated by the type of organizational outcome under inves-

tigation, and that the predictive power of cultural values can be

stronger for certain populations, including employed popula-

tions versus students, older rather than younger respondents,

men compared with women, more educated populations rather

than less educated ones, and in tight rather than loose societies.

Other contingencies under which cultures’ consequences

vary need to be examined in the next 100 years. Aycan (2005),

for example, argued that the impact of culture on HRM would

be less evident in large, publically traded organizations, or

those operating in industries that use sophisticated technologies

(e.g., IT sector), compared with small to medium sized family-

owned organizations or those operating in industries that use

semiskilled employees (e.g., manufacturing). Similarly, Gib-

son, Maznevski, and Kirkman (2009) proposed that culture’s

impact will be more pronounced on individuals who are high in

conformity, conscientiousness, openness, and adaptability, as

well as among individuals who had have high identification

with their own culture and low exposure to other cultures. The

authors also identified contingencies under which culture’s

impact was stronger on groups, such as when group identifica-

tion, cohesion, and homogeneity is high, and group polarization

is low.

Theory is needed to explain precisely why and how situa-

tional contingencies intensify or exacerbate cross-cultural dif-

ferences. For example, the situated dynamics (SD) framework

of culture by Leung and Morris (2015) expands the value-based

view of culture to include schemas and norms, which are

situation sensitive. The SD framework postulates that values

play a stronger role in situations involving social adaptation

signals or cues to moral/ethical decisions, whereas behavioral

schemas or norms play a greater role in situations involving

interpretive or behavioral tasks. The framework reconciles ten-

sions between cultural stability and culture change by positing

that some aspects of culture (e.g., values) are relatively consis-

tent across time, whereas others (e.g., schemas and norms) are

in flux with situational demands. Similarly, Zellmer-Bruhn and

Gibson (2014) proposed a promising framework highlighting

the role of situational context, and in particular, the concept of

intercultural interaction space to denote the physical, cognitive,

and affective characteristics of the situation in which interac-

tions occur and how these characteristics attenuate or augment

cultural differences. In all, few JAP articles have focused on

complex interactions between culture and context in the last 100

years. Future CCIO/OB research in JAP should go beyond the

question of whether or not culture matters and focus on when

and how it matters (see also Erez, Lee, & Van de Ven, 2015;

Nouri et al., 2015; Zhou & Su, 2010).

From Intracultural Comparisons With Intercultural

Interactions and the Global Work Context

Although our review illustrates increasing complexity with

which culture is theorized and studied, there still exists a dominant

paradigm of studying culture as a static main effect, largely in

correlational field studies. The future of culture research, we

believe, will need to capture cultural dynamics (i.e., change and

interaction) at all levels of analysis, including the dynamics of

cultural frame shifting within individuals, the dynamics of inter-

cultural negotiations and virtual teams, the multitude of factors that

affect the success or failure of cross-cultural mergers and acqui-

sitions, and large-scale cultural changes around the globe that

result from rapid top-down and bottom-up ecological, demo-

graphic, and market forces.

Additionally, the increasingly globalized, networked world ne-

cessitates that we understand how the global context of a culturally

diverse and geographically dispersed workforce changes our the-

ories, research questions, and methodologies. Kraimer, Takeuchi,

and Frese (2014) defined global work context to include

any job-related activities that involve interacting with people from

other countries. Examples include interacting with customers or co-

workers from foreign countries, working in cross-national teams,

having extensive international travel requirements as part of the job,

and living and working in a foreign country for extended periods of

time (whether self- or corporate-initiated). (p. 6)

In the globalized work context, we expect more people to live

and work in more than one culture, be it their home culture and

host culture, or the global cultural context more generally.

This trend opens new and exciting research avenues for

CCIO/OB scholars to address. First, how do we conceptualize and

measure “global culture”? Although research has been published

on the national culture and on subcultures at the organizational and

team levels, there has been a dearth of attention to the meaning

and impact of global culture. Second, how do people negotiate

multiple identities depending on the demands of different con-

texts? Erez and colleagues argue that global work context contrib-

utes to the development of global identities independent of any

national local identity (Erez & Gati, 2004; Erez et al., 2013;

Shokef & Erez, 2008). Based on the recent theoretical advance-

ments explained in previous sections, CCIO/OB research should

investigate whether increasing exposure to the global work context

attenuates cultural differences. For example, Glikson and Erez

(2013) showed that variance in emotion display norms was

smaller in the global context than in the local cultural contexts.

In addition, it will be critical to examine how people manage

cross-cultural interactions in the global work context. Given the

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

522

GELFAND, AYCAN, EREZ, AND LEUNG

fact that cross-cultural interactions tend to be more “frequent,

horizontal, unstructured, temporary, sporadic, and across global

locations” (Zellmer-Bruhn & Gibson, 2014, p. 3), we must

invest in theorizing and researching “cross-cultural interac-

tions” more than we do in “cross-cultural differences.” Within

this spirit, CCIO/OB research should be in closer contact with

the cultural intelligence and diversity management literatures to

develop theories capturing processes and outcomes of cross-

cultural interactions. Finally, how do global teams work effec-

tively? We expect a significant growth in the presence of

multicultural virtual teams, given the fast development of in-

formation communication technologies (ICT; Gibson, Huang,

Kirkman, & Shapiro, 2014). Future research should investigate

how ICTs enable the emergence of shared norms in multicul-

tural teams (see the special issue on culture and collaboration in

Journal of Organizational Behavior: Salas & Gelfand, 2013).

We should also have more research on global leaders who

manage multicultural teams and identify what makes them

successful in the global context (Lisak & Erez, 2015).

Take Meaning of Constructs Across Cultures

More Seriously

An important challenge for future CCIO/OB research is to

explore “universal” constructs (i.e., etics) as well as “culturally

embedded” unique constructs or (i.e., emics). We believe that

discoveries of emic constructs and expanding our existing con-

structs to include emic dimensions will ultimately enable us to

develop a truly global universal science.

Research is indeed increasingly illustrating that we need to

expand upon many of our existing constructs for them to be

relevant beyond the West. For example, the latent construct of

personality for Chinese goes beyond the five-factor model of

McCrae and Costa (1997) to include emic dimensions such as

Reng Qing (adherence to norms of interaction), Ah-Q (external-

ization of blame), Harmony (inner peace and interpersonal har-

mony), and Face (e.g., F. M. Cheung et al., 1996). Similarly,

organizational citizenship behaviors include additional dimensions

such as self-training, protecting and saving company resources,

and keeping the workplace clean among Chinese, and the behav-

iors that constitute the same dimensions as those in the Western

literature vary in meaningful ways (Farh, Zhong, & Organ, 2004).

Relatedly, Lowenstein and Mueller (2016) found significant dif-

ferences across cultures in the meaning of creativity, with a broad

meaning in China, including usefulness and, harmony, and a more

narrow meeting of creativity in the United States (see also Gibson

& Zellmer-Bruhn, 2001, for differences in metaphors for teams

across cultures). Put differently, from a psychometric point of

view, it is critical to ensure that our constructs are not deficient—

that is, missing important dimensions that are relevant in other

cultures. In this spirit, we caution that establishing measurement

equivalence of scales through factor analysis does not guarantee

universality of the constructs being studied.

More generally, there needs to be more institutional support for

publishing indigenous or emic dimensions of constructs in the

field. For example, emic constructs such as guanxi, wasta, giri,

taimen, paternalism, jeitinho, and yuan, among others, need to be

integrated into I/O OB research (see Smith, 2008; Tung & Aycan,

2008). We also need to be cognizant that research with U.S.

samples may represent culture-specific phenomena, that is, that of

American, rather than “universal,” phenomena (e.g., Danziger,

2006).

2

Importantly, studying indigenous or emic phenomena,

wherever they originate, is not incompatible with building a global

science; indeed, it is the path to a truly universal science of

psychology. As Pruitt (2004, p. xii) states, “Characteristics that are

dominant in one culture tend to be recessive in another, and vice

versa.” Moreover, by gaining knowledge on emic constructs, we

can begin to build broader theories across cultures. For example,

though guanxi has specific emic elements that define it, it also has

some commonality with other constructs related to social capital

(see Huang, & Wang, 2011; Qi, 2013; Smith, Huang, Harb, &

Torres, 2012).

We would also argue that the development of such constructs is

not only important for science—indeed, Marsden (1991) argues

that sustainable national and organizational development is more

likely if emic or indigenous constructs are understood and utilized

better:

Indigenous knowledge...maybethebasis for building more

sustainable development strategies, because they begin from where

the people are, rather than from where development experts would

like them to be. It is commonly maintained that these indigenous

knowledge systems, if articulated properly, will provide the bases for

increasing productivity. (p. 31)

Capturing emic realities is therefore critical for ultimately advanc-

ing practice.

Methodological and Disciplinary Diversity Should

be a Priority

As culture is a complex phenomenon, we must strive to have

methodological and epistemological diversity in the field. For

example, we need to complement existing quantitative methods

with those that are more qualitative in nature, the latter of which

received no attention in CCI/OOB research published in JAP

during the last 100 years (see Cole, 2006; Vygotsky & Wollock,

1997; and see Karasz & Singelis, 2009 for a special issue of the

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology on qualitative and mixed

methodologies in cross-cultural research). Likewise, other exper-

imental methodologies, such as priming cultural values (e.g., Co-

hen, Montoya, & Insko, 2006; Oyserman & Lee, 2008), should

complement field and qualitative data. Indeed, we observed that

few studies in JAP utilize multiple methods, which is essential for

triangulation and ruling out rival hypotheses (Gelfand et al., 2002).

More broadly, it will be critical for CCIO/OB scholars to partner

with scholars in other disciplines, including those in computer

science, linguistics, neuroscience, biology, and history, among

others, to increase our theoretical and methodological diversity.

Rapid developments in cognitive neuroscience have stimulated the

emergence of new fields, such as “cultural neuroscience” and

2

In our review of JAP articles, we observed that almost all of the JAP

articles with non-U.S. samples included a sentence of caveat about the

generalizability of findings to other cultural contexts, whereas no such

warning was evident in articles with U.S. samples, which tend to assume

that the phenomenon is generalizable rather than unique to Americans. As

a general practice, we believe that all articles should question whether

findings are generalizable to other contexts and under what conditions they

may or may not.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

523

CROSS-CULTURAL I/O/OB

“sociogenetics” (e.g., Minkov et al., 2015; see also Chiao &

Blizinsky, 2010; Mrazek, Chiao, Blizinsky, Lun, & Gelfand,

2013). As well, integrating computer science perspectives into

cross-cultural research is increasingly yielding new insights into

the evolution of cultural differences relevant to I/O and OB (see

Nowak, Gelfand, Borkowski, Cohen, & Hernandez, 2016; Roos,

Gelfand, Nau, & Carr, 2014; Roos, Gelfand, Nau, & Lun, 2015).

It is our hope that JAP will encourage submissions by interdisci-

plinary and international teams featuring state-of-the-art ap-

proaches to allow for a deeper understanding of what culture is and

how it should be best captured.

Conclusion

Cross-cultural research in JAP has evolved significantly over

the last 100 years. Although culture was largely ignored in the

early years and through the mid-20th century, there has been a

great increase in the momentum in the field, particularly in the last

decade, that promises to continue in the next 100 years. Cross-

cultural research is needed more than ever to understand and

leverage similarities and differences in an ever-more increasingly

globalized and interdependent world.

References

Adair, W. L., Okumura, T., & Brett, J. M. (2001). Negotiation behavior

when cultures collide: The United States and Japan. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 86, 371–385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.371

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimen-

tal Social Psychology, 2, 267–299. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0065-

2601(08)60108-2

Antonakis, J. (2011). Predictors of leadership: The usual suspects and the

suspect traits. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, & M.

Uhl-Bien (Eds.), Sage handbook of leadership (pp. 269–285). Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Araujo, S. F. (2013). Völkerpsychologie. In K. D. Keigh (Ed.), The

encyclopedia of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 1333–1338). Chichester,

UK: Wiley Blackwell. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9781118339893

.wbeccp560

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from

the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–

480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Atwater, L., Wang, M., Smither, J. W., & Fleenor, J. W. (2009). Are

cultural characteristics associated with the relationship between self and

others’ ratings of leadership? Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 876 –

886. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014561

Aycan, Z. (2005). The interplay between cultural and institutional/

structural contingencies in human resource management practices. The

International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16, 1083–1119.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585190500143956

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R., Mendonca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J., Stahl, G., &

Kurshid, A. (2000). Impact of culture on human resource management

practices: A 10-country comparison. Applied Psychology: An Interna-

tional Review, 49, 192–221. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00010

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R. N., & Sinha, J. B. P. (1999). Organizational culture

and human resource management practices: The model of culture fit.

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 501–526. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1177/0022022199030004006

Ayman, R., & Chemers, M. M. (1983). Relationship of supervisory be-

havior ratings to work group effectiveness and subordinate satisfaction

among Iranian managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 338–341.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.68.2.338

Bail, C. A. (2014). The cultural environment: Measuring culture with big

data. Theory and Society, 43, 465–482. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/

s11186-014-9216-5

Barrett, G. V., & Bass, B. M. (1970). Comparative surveys of managerial

attitudes and behaviors (No. TR-36). Rochester, NY: Rochester Univer-

sity Management Research Center.

Benet-Martínez, V., Leu, J., Lee, F., & Morris, M. W. (2002). Negotiating

biculturalism: Cultural frame switching in biculturals with oppositional

versus compatible cultural identities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychol-

ogy, 33, 492–516. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005005

Bennett, M. (1977). Testing management theories cross-culturally. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 62, 578 –581. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-

9010.62.5.578

Berry, J. W. (1975). An ecological approach to cross-cultural psychology.

Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Psychologie en haar Grensgebieden, 30,

51– 84.

Bhagat, R. S., & McQuaid, S. J. (1982). Role of subjective culture in

organizations: A review and directions for future research. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 67, 653– 685. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010

.67.5.653

Boddewyn, J., & Nath, R. (1970). Comparative management studies: An

assessment. Management International Review, 10, 3–11.

Burke, R. J., & Ng, E. (2006). The changing nature of work and organi-

zations: Implications for human resource management. Human Resource

Management Review, 16, 86–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2006

.03.006

Castells, M. (2004). The network society: A cross-cultural perspective.

Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Chao, G. T., & Moon, H. (2005). The cultural mosaic: A metatheory for

understanding the complexity of culture. Journal of Applied Psychology,

90, 1128 –1140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1128

Chen, F. F. (2008). What happens if we compare chopsticks with forks?

The impact of making inappropriate comparisons in cross-cultural re-

search. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1005–1018.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013193

Cheung, F. M., Leung, K., Fan, R. M., Song, W. Z., Zhang, J. X., & Zhang,

J. P. (1996). Development of the Chinese personality assessment inven-

tory. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 27, 181–199. http://dx.doi

.org/10.1177/0022022196272003

Cheung, M. W.-L., Leung, K., & Au, K. (2006). Evaluating multilevel

models in cross-cultural research: An illustration with social axioms.

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37, 522–541. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1177/0022022106290476

Chhokar, J. S., Brodbeck, F. C., & House, R. J. (2008). Culture and

leadership across the world: The GLOBE Book of In-Depth Studies of 25

Societies. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Chiao, J. Y., & Blizinsky, K. D. (2010). Culture-gene coevolution of

individualism-collectivism and the serotonin transporter gene. Proceed-

ings Biological Sciences/The Royal Society, 277, 529 –537. http://dx.doi

.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1650

Chiu, C.-Y., Gelfand, M. J., Yamagishi, T., Shteynberg, G., & Wan, C.

(2010). Intersubjective culture: The role of intersubjective perceptions in

cross-cultural research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 482–

493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375562

Cohen, T. R., Montoya, R. M., & Insko, C. A. (2006). Group morality and

intergroup relations: Cross-cultural and experimental evidence. Person-

ality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 1559–1572. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1177/0146167206291673

Cole, M. (2006). Culture and cognitive development in phylogenetic,

historical, and ontogenetic perspective. In D. Kuhn, R. S. Seigler, W.

Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child development (pp.

636 – 683). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Cronbach, L. J., & Drenth, P. J. D. (Eds.). (1972). Mental tests and cultural

adaptation. The Hague, the Netherlands: Mouton.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers.

This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

524

GELFAND, AYCAN, EREZ, AND LEUNG

Danziger, K. (2006). Universalism and indigenization in the history of

modern psychology. In A. C. Brock (Ed.), Internationalizing the history

of psychology (pp. 208 –225). New York, NY: New York University

Press.

Devinney, T. M., Kirkman, B. L., Caprar, D. V., & Caligiuri, P. (2015).

What is culture and how do we measure it? [Special issue]. Journal of

International Business Studies, 46(9).

Dheer, R., Lenartowicz, T., Peterson, M. F., & Petrescu, M. (2014).