Minnesota State University, Mankato Minnesota State University, Mankato

Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly

and Creative Works for Minnesota and Creative Works for Minnesota

State University, Mankato State University, Mankato

All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other

Capstone Projects

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other

Capstone Projects

2014

A Comparison of the Effectiveness of a Token Economy System, a A Comparison of the Effectiveness of a Token Economy System, a

Response Cost Condition, and a Combination Condition in Response Cost Condition, and a Combination Condition in

Reducing Problem Behaviors and Increasing Student Academic Reducing Problem Behaviors and Increasing Student Academic

Engagement and Performance in Two First Grade Classrooms Engagement and Performance in Two First Grade Classrooms

Britta Leigh Fiksdal

Minnesota State University - Mankato

Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds

Part of the School Psychology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Fiksdal, B. L. (2014). A Comparison of the Effectiveness of a Token Economy System, a Response Cost

Condition, and a Combination Condition in Reducing Problem Behaviors and Increasing Student

Academic Engagement and Performance in Two First Grade Classrooms [Master’s thesis, Minnesota

State University, Mankato]. Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State

University, Mankato. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds/343/

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other

Capstone Projects at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University,

Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by

an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State

University, Mankato.

A Comparison of the Effectiveness of a Token Economy System, a Response

Cost Condition, and a Combination Condition in Reducing Problem Behaviors and

Increasing Student Academic Engagement and Performance in Two First Grade

Classrooms.

Britta L. Fiksdal

A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Psychology

School Psychology

Minnesota State University, Mankato

Mankato, Minnesota

May 2014

ii

A Comparison of the Effectiveness of a Token Economy System, a Response Cost

Condition, and a Combination Condition in Reducing Problem Behaviors and Increasing

Student Academic Engagement and Performance in Two First Grade Classrooms.

Britta L. Fiksdal

This dissertation has been examined and approved by the following members of the

dissertation committee.

_____________________________________

Daniel Houlihan, Ph.D., Advisor

_____________________________________

Kathy Bertsch, Ph.D., Committee Member

_____________________________________

Kevin J. Filter, Ph.D., Committee Member

_____________________________________

Teresa Wallace, Ph.D., Committee Member

__________________

Date

iii

Copyright

Copyright © Britta L. Fiksdal 2014

All Rights Reserved

iv

Dedication

This dissertation is dedicated to my incredibly supportive and understanding fiancé,

Brett, and my family who have been there for me no matter what throughout my doctoral

training. They have provided me with both emotional and financial stability to complete

this journey and shown me that I can make my dreams come true. Their confidence in me

is priceless and has meant the world to me.

I also want to thank my advisor, Dr. Houlihan, for his endless support throughout my

training. Several hours have been dedicated to this project and it could not have been

completed without his expertise and guidance. I have enjoyed working with him and am

honored to have had him as my mentor.

v

Table of Contents

Copyright…………………………………………………………………………………iii

Dedication………………………………………………………………………………...iv

List of Figures………………………………………………………………………...….vii

Abstract of the Dissertation……………………………………………………………....ix

Chapter I Introduction and Literature Review…………………………………………….1

Token Economies………………………………………………………………….1

Response Cost……………………………………………………………………..6

Combination of Token Economies and Response Cost……………………….......8

Florida Pilot Study…………………………………………………………….....15

Purpose of the Current Study………………………………………………….....17

Chapter II Methods………………………………………………………………………19

Participants ………………………………………………………………………19

Dependent Measures……………………………………………………………..20

Independent Measures…………………………………………………………...21

Procedure………………………………………………………………………...22

Pre-Baseline…………………………………………………………………..22

Baseline…………………………………………………………………….....22

Token Economy………………………………………………………………22

Response Cost………………………………………………………………...23

Combination…………………………………………………………………..24

Token Exchange………………………………………………………………24

Data Analysis…………………………………………………………………25

vi

Inter-Rater Reliability………………………………………………………...26

Treatment Integrity…………………………………………………………...26

Chapter III Results…………………………………………………………………….....27

Academic Engagement…………………………………………………………..27

Disruptive Behavior……………………………………………………………...32

Academic Performance...………………………………………………………...37

Student Preference…………………………………………………………….....42

Teacher Preference…………………………………………………………….....43

Treatment Fidelity………………………………………………………………..47

Inter-Rater Reliability……………………………………………………………47

Chapter IV Discussion…………………………………………………………………...48

Appendix A…………………………………………………………………………………

Consent and Assent Forms…………………………………………………….....53

Appendix B…………………………………………………………………………………

Observation Forms and Teacher Materials………………………………………71

Appendix C…………………………………………………………………………………

Data Collection Forms…………………………………………………………...79

vii

List of Figures

Figure 1: Figure 1. Percent of intervals students were academically engaged in C.S.’

classroom during the Token Economy, Response Cost, Combination, and Baseline

conditions across the three phases.

Figure 2: The average percentage of intervals students were academically engaged by

condition across the three phases for C.S.’ classroom.

Figure 3: Percent of intervals students were academically engaged in S.M.’s classroom

during the Token Economy, Response Cost, Combination, and Baseline conditions across

the three phases.

Figure 4: The average percentage of intervals students were academically engaged by

condition across the three phases for S.M.’s classroom.

Figure 5: Rate of disruptive student behaviors per minute during the Token Economy,

Response Cost, Combination, and Baseline conditions for C.S.’ classroom across the

three phases.

Figure 6: Average rate of disruptive student behaviors per minute by condition across the

three conditions for C.S.’ classroom.

Figure 7: Rate of disruptive student behaviors per minute during the Token Economy,

Response Cost, Combination, and Baseline conditions for S.M.’s classroom across the

three phases.

Figure 8: Average rate of disruptive student behaviors per minute by condition across the

three conditions for S.M.’s classroom.

Figure 9: Academic performance as measured by average class points earned on a three

point quiz given to students daily during the Token Economy, Response Cost,

Combination, and Baseline conditions across the three phases for C.S.’ classroom.

Figure 10: Average academic performance as measured by average points earned on daily

three point quiz by condition across the three phases in C.S.’ classroom.

viii

Figure 11: Academic performance as measured by average class points earned on a three

point quiz given to students daily during the Token Economy, Response Cost,

Combination, and Baseline conditions across the three phases for S.M.’s classroom.

Figure 12: Average academic performance as measured by average points earned on daily

three point quiz by condition across the three phases in S.M.’s classroom.

ix

Abstract of the Dissertation

A Comparison of the Effectiveness of a Token Economy System, a Response Cost

Condition, and a Combination Condition in Reducing Problem Behaviors and Increasing

Student Academic Engagement and Performance in Two First Grade Classrooms.

By

Britta L. Fiksdal

Doctor of Psychology in School Psychology

Graduate School of Psychology

Minnesota State University, Mankato, 2014

Carlos Panahon, Ph.D., Chair

Previous research has shown that token economy systems and response cost procedures

are effective in reducing disruptive behaviors in classrooms and increasing academic

engagement. Few studies have compared the effectiveness of combining these two

classroom management techniques, examined academic performance, and directly

observed academic engaged time. The current study compared the effectiveness of four

conditions: baseline, response cost procedure, token economy system, and a combination

condition among two, first grade classrooms in a small town in central Wisconsin using

direct observation and permanent product of a three question quiz. Behaviors assessed

included problem behaviors in the classroom, academic engaged time, academic

performance, and student and teacher preference. An alternating treatments design was

utilized in which one of the four conditions were employed each day during the math

lesson in a randomized predetermined order.

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Token economies have a long history of changing behaviors among humans.

Lancaster started the trend with the use of tickets within large classrooms in the early

1800’s followed by the use of cherries and cakes in the early 1950’s to teach Latin and

Greek to children (Lancaster, 1805; Skinner, 1966). One of the first therapeutic

applications of a token economy was delivered by Avendano Carderera in 1959 who gave

a ticket to children for good behavior (Rodriguez, Montesinos, & Preciado, 2005). Staats

and colleagues applied a token economy system to a student with reading problems in the

late 1950’s. These studies indicate that token economies have been used for quite some

time to modify behavior. However, despite the research indicating its effectiveness, token

economies are not currently used as often as they could be in schools (Matson, &

Boisjoli, 2009).

Token Economies

Token economy systems are when participants earn tokens contingent on certain

behaviors which are then exchanged for predetermined backup reinforcers at a later point

in time. The main element to a token economy system is that the tokens are delivered

contingent on a specific behavior and linked to meaningful reinforcer(s) (Kazdin, 1977;

Wolery, Bailey, & Sugai, 1988). Ayllon and Azrin wrote a book in 1968 titled, The

Token Economy, which emphasized the effectiveness of using token economies with

children with developmental delay as well as various problematic behaviors. The book

also discussed the effectiveness of implementing a token economy system with typically

2

developing children. The majority of research evaluating the effectiveness of token

economies was conducted between the 1960s-1980s however; until recently the number

of studies between then and now has been minimal (Matson & Boisjoli, 2009).

A token economy system, when applied correctly, shares many of the same

features of other behavior modification interventions (Hall, 1979). They typically consist

of a list of instructions for the individuals involved, including: the target behavior(s) that

will and/or will not be reinforced, a method to ensure the token is contingent on behavior

which allows the token to become a reinforcing stimulus, and a set of rules that explain

how, when, and under what conditions the tokens can be exchanged for the backup

reinforcers (O’Leary, & Drabman, 1971). In a token economy, points or tokens are

delivered contingent on a target behavior over a specified period of time. After a certain

time interval has passed, the students can exchange the number of tokens they have for

backup reinforcers. The size of the backup reinforcer should be in relation to the number

of tokens the individual earned and are exchanging. There are many advantages to token

economy systems such as; bridging the gap between a target response and the backup

reinforcer, maintaining performance over an extended period of time until the backup

reinforcer can be delivered, and allowing behavior to be reinforced at any time. Token

economies are also less likely to be affected by satiation and can provide a visual

reminder of the progress or lack of progress the student has made regarding their

behavior (Kazdin, & Bootzin, 1972).

Within a token economy, the token is a stimulus that signals the delivery of a

backup reinforcer at a later point in time. The token can be any object that can be easily

3

delivered, easily kept, and easily exchanged. Some advantages of using a tangible

reinforcer include: tokens are portable, no maximum exists, the number of tokens can

represent the amount of reinforcement, they are durable and can be used continuously,

devices can be used to automatically deliver tokens contingent on behavior, the physical

characteristics of the token can be standardized or personalized, and can be made to be

indestructible (Kazdin & Bootzin, 1972). In some cases, natural reinforcement of teacher

praise and attention will not be effective in changing classroom behavior, in these

situations, token economies are often times found to be effective. Token economies are

most effective when there are multiple backup reinforcers as opposed to one reinforcer.

By having a large variety of backup reinforcers to choose from, it is less likely students

will become satiated and the chances of each student finding at least one item that

functions as a reinforcer is increased (O’Leary, & Drabman, 1971).

The first step in a token economy is to identify a target behavior and developing

an operational definition. After the target behavior is identified, tokens must be made,

backup reinforcers need to be gathered, and rules regarding delivery and exchanging of

tokens must be developed. Next, the tokens must be established as secondary reinforcers

for the backup reinforcers. When establishing the tokens as reinforcing, it is important to

go through a practice with students in which they are told and shown how to earn tokens,

the rules for exchanging, and then allow them to exchange the tokens for a reinforcer so

they have access to the contingency (Kazdin, & Bootzin, 1972).

Research studies have found that, in part because of the flexibility of the different

features, token economies have been effective in reducing problem behavior and

4

increasing positive behavior in a variety of subjects under a variety of different

conditions and with multiple behaviors (Kazdin, 1982; O’Leary, & Drabman, 1971). A

review of the literature conducted by Matson and Boisjoli (2009), found that token

economies have been used successfully for different behaviors such as remaining in seat,

increasing attention, increasing appropriate verbalizations and social skills, and

increasing self-help skills, decreasing inappropriate call-outs in class, decreasing

aggressive behaviors, decreasing disruptive behaviors within class, increasing academic

behaviors such as completing homework assignments, increasing test performance,

increasing academic engaged time and academic performance, and increasing academic

accuracy. Token economies have been successful for multiple subjects as well including;

children with developmental delay, cognitive deficits, autism, ADHD, emotional and

behavioral problems, conduct disorders and typically developing children. They have also

been used with adults with psychiatric diagnosis, legal offenders, employees, and

teachers. Token economies have been administered by multiple individuals such as

parents, teachers, school psychologists, employers, doctors, nurses, and clinical

psychologists.

While there are a multitude of studies published proving the effectiveness of

token economy systems at reducing problem behaviors and increasing positive behaviors

in classroom and school settings, systematic evaluations of the experimental literature to

validate the use in schools have not been completed recently. Maggin and colleagues

conducted such a literature review to evaluate the quality of research designs used to

determine whether or not token economy systems are, in fact, an evidence based

5

intervention for behavior management in both classroom and school settings (Maggin,

Chafouleas, Goddard, & Johnson, 2011). The study used four questions to guide their

review of the literature which included looking at What Works Clearinghouse (WWC)

standards, student characteristics and intervention features, statistical summaries of

treatment effects, and methodological strengths and weaknesses. After their initial search,

they started with a total of 834 articles to be screened for retrieval, 118 articles made it

past the initial inclusion screening, 36 articles were considered potentially relevant, and

24 studies were included in the synthesis. The reasons for exclusions included: ineligible

intervention, ineligible dependent variable, ineligible population, ineligible design,

irretrievable data, and not an intervention study. Of the 24 studies, there were a total of

90 cases of which 67 of them used students as the unit of analysis and 23 used the

classroom as the analysis. Additionally, of the 25 studies, only four different single

subject designs were used: reversal (n = 15), AB (n = 5), multiple baseline (n = 3), and

ABA (n = 1). Overall, according to WWC standards, there is currently insufficient

support for token economies as an evidence based classroom management strategy

mainly due to methodological rigor of the current studies. However, when you take into

account all of the studies, token economy systems were found to be effective as both a

classroom management system and individual behavior intervention program for three of

the four effect sizes calculated through significant improvement in student functioning as

a result of introducing token economy systems in the classroom.

6

Response Cost

Response cost is a punishment procedure that has been used in school settings to

effectively change behavior (McGoey, & DuPaul, 2000). Originally, response cost

referred to changing the work required to emit a behavior, in other words changing the

cost of the behavior to affect the rate of that behavior (Weiner, 1962). The use of

response cost in the school settings is somewhat different from the original definition. In

a school setting, the incorporation of a response cost includes taking away tokens or

points contingent on problem behaviors. Typically these tokens are given

noncontingently at the beginning of a time interval, lesson, or session and the student gets

to keep them as long as they do not engage in any of the problem behaviors. At the end of

the time period, they can exchange the tokens they have left for backup reinforcers.

Response cost is a punishment based system whereas a token economy is reinforcement

based (Kazdin, 1972; Pace, & Forman, 1982).

Response cost is not the same as extinction or time-out. Extinction is the

withdrawal of reinforcers maintaining an undesirable behavior and time-out is removing

the student from a reinforcing environment contingent on undesirable behavior. Response

cost is not extinction because you are not removing the functional reinforcer for problem

behavior, instead you are withdrawing secondary reinforcers contingent on undesirable

behavior. Response cost is not time-out because you are not removing the student from

the environment. Instead, they stay in the classroom and lose a token contingent on

problem behavior. Response cost is different from a token economy in that you do not

receive tokens contingent on desirable behavior, instead, the tokens are given

7

noncontingently in the beginning of a time interval and are taken away contingent on

problem behavior. Whatever amount of tokens the student has left is then exchanged for

backup reinforcers at a specified time (Kazdin, 1972).

A review of the literature shows response cost procedures have been found

effective for multiple individuals within classroom settings such as developmental delay,

cognitive delay, emotional and behavioral problems, and students with academic

difficulties. A variety of behaviors have also been changed drastically with response cost

procedures including out of seat behavior, calling out in class, off task behavior,

disruptive behavior, academic performance, smoking, and weight loss. Most studies that

have examined the recovery of suppressed behaviors through response cost have found

that the behavior does not recover when the contingency is withdrawn (Kazdin, 1972).

Typically, punishment procedures have been associated with side effects such as

escape and avoidance behaviors along with emotional consequences. Previous studies

have indicated that escape behaviors are not associated with response cost like it is with

the delivery of aversive stimuli. Also, there have been no negative emotional

consequences reported with response cost procedures (Litenberg, 1965). It is likely that

these negative side effects are not associated with response cost because the removal of a

positive reinforcer (token) is not as aversive in magnitude compared to the delivery of an

aversive stimulus (Schmauk, 1970). Current research has not focused on emotional

consequences as much as reducing problem behaviors.

8

Combination of Token Economies and Response Cost

Some researchers and classroom teachers have combined token economy systems

with response cost procedures. In these classroom management techniques the individual

is able to earn points contingent on desirable behavior and can also lose points contingent

on undesirable behavior. At the end of the interval, the tokens they have left can be

exchanged for backup reinforcers (Weiner, 1962). One advantage to this combination

procedure includes the ability to provide tokens contingent on a behavior that is

completely unrelated to the behavior in which the tokens are taken away. Response cost

used to be used quite frequently within token economy systems, however, a more recent

review of the literature suggests that it is not used as often in school settings as it used to

be and neither are token economy systems (Matson, & Boisjoli, 2009).

There have been multiple research studies on the effectiveness of token

economies, response cost procedures, and combination procedures in reducing problem

behaviors among human subjects. The first token economy system to be used in a larger

classroom setting was in 1967 by O’Leary and Becker. The classroom consisted of 17

students all of whom had emotional and behavioral disturbances. After the introduction

of the token economy, disruptive behavior decreased significantly from 76% of intervals

during baseline to 10% during intervention. O’Leary and colleagues (1969) also

conducted a token economy system with seven students in a second grade classroom all

of whom exhibited disruptive behaviors. The implementation of the token economy

system reduced disruptive behaviors significantly compared to baseline rates. A token

economy system was used to reduce violent behavioral outbursts and loud noise among

9

psychiatric patients (Winkler, 1970). A review of token economy systems within

classroom behavior found that many behaviors were successfully increased such as being

quiet, hanging up coats, sitting at their desk, academically engaged, completing a task,

following instructions, and facing the front of the class and teacher (Kazdin, & Bootzin,

1972). More recently, Kahng and colleagues (2003) provided tokens contingent on eating

certain amounts of food and eating novel food for a four year old girl diagnosed with

pervasive developmental disorder with food refusal.

Siegel and colleagues (1969) used a response cost procedure to reduce speech

disfluencies among normal-speaking college ages students. Four females and one male

participated in the study at the University of Minnesota. Results indicated the procedure

was very effective at suppressing disfluencies during spontaneous speech. They used

money as the backup reinforcers for the points they earned throughout the speech. A

response cost procedure was used to reduce problematic behaviors among delinquent

soldiers (Winkler, 1970). Response cost procedures have also been used to reduce

aggressive statements, tardiness, and specific word usage among three delinquent boys

(Phillips, 1968). Phillips and colleagues (1971) studied the effectiveness of a response

cost procedure on delinquent youths in Achievement Place. Results indicated that point

loss contingent on problem behavior produced significant increases in desirable

(incompatible) behaviors such as promptness, completing quizzes, saving money, and

keeping a clean bedroom. A study conducted by Pace and Forman (1982) found that a

response cost procedure was effective for 55 second graders enrolled in a Title -1

program in a low socioeconomic status neighborhood school. Results indicated the fines

10

associated with the response cost procedure was effective in reducing disruptive

behaviors such as out of seat, inappropriate vocalization, being noisy, touching other

people’s property, and aggression.

More recently, in 2004, Conyers and colleagues compared the effectiveness of a

response cost condition with differential reinforcement of other behavior on reducing

disruptive behaviors among 25 students in a preschool classroom. Disruptive behavior

decreased from 64% of intervals to 5% for the last six sessions of the response cost

procedure. Initially, differential reinforcement of other behavior resulted in a more drastic

decrease of disruptive behavior but over time disruptive behaviors increased to 27% of

intervals. Therefore, the response cost condition maintained lower rates of disruptive

behavior more effectively than differential reinforcement of other behavior.

McLaughlin and Malaby (1972) compared the effectiveness of a token economy

system and a response cost condition with a classroom containing 25-27 fifth and sixth

grade students. In the Point Loss phase the teacher removed points contingent on problem

behaviors. In the Quiet Behavior Point phase students earned points contingent on

desirable behaviors that were incompatible with an ineffective learning environment.

Results indicated that both were effective in reducing problem behavior and increasing

desirable behavior. McGoey and DuPaul, (2000) compared the effectiveness of a token

economy system and response cost procedure in reducing inappropriate social behaviors,

off task behavior, following rules, and tantrumming among four preschool students

diagnosed with ADHD. Results showed little difference between the two interventions in

11

the ability to change behavior. Both the response cost and token economy conditions

resulted in a decrease in problematic behaviors compared to baseline rates.

While a number of studies have focused on reducing problem behaviors among

individuals, a number of studies have focused on changing academic behaviors such as

studying, staying on task, completing homework assignments, and completing tests as

well. A review of the literature shows that response cost and token economy systems

have been effective for a wide variety of school age populations such as developmental

and cognitive delay in summer school programs and hospital settings, teenage students

and elementary students, a small child with Phenylketonuria (PKU), and children with

autism and social skills deficits (Matson, & Boisjoli, 2009).

In 1965, Birnbrauer, Wolf, Kidder, and Tague found that a token economy system

resulted in higher levels of accuracy on homework and increased rates of studying overall

for 15 children diagnosed with cognitive delay compared to baseline in which no token

economy was employed. A study conducted in 1968 compared noncontingent

reinforcement to contingent reinforcement using a token economy system. The study

showed that noncontingent reinforcement was not as effective in changing and increasing

study behavior among the 12 preschool children with above average intelligence

compared to the token economy system (Bushell, Wrobel, & Michaelis, 1968). Wolf and

colleagues found that a token economy system was effective in increasing report card

grades and regular classroom assignments along with language, reading, and arithmetic

performance when a token economy system was employed for students in a remedial

education elementary classroom (Wolf, Guiles, & Hall, 1968). Walker and colleagues

12

conducted a study that assessed a token economy system on task-oriented behavior for

six children all with average or above average functioning but were described by their

teachers as being disruptive and hyperactive. Results showed the percentage of on-task

intervals increased from an average of 39% of intervals during baseline to an average of

90% of intervals during the token economy condition (Walker, Mattson, & Buckley,

1969).

Panek (1970) compared a response cost condition to a token economy system for

learning word associations among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Subjects

included 32 male patients between the ages of 30-77 years old who have lived in the

hospital between 2-38 years. Patients were split into two groups; response cost group or

token economy groups. Results showed an increase in word association for both groups

of patients. Therefore, this study showed no difference between reward based and

punishment based programs for learning word associations and neither condition resulted

in generalization to new words. Broden, Hall, Dunlap, and Clark (1970) first

implemented a token economy condition and then a combination response cost and token

economy condition while assessing study rates among seventh and eighth grade students

who were all behind their peers academically by at least one year. In the token economy

condition, the researchers noticed an increase in study behavior during the token

economy system in which students earned one extra minute of lunch contingent on

appropriate study behaviors. While study behavior increased from 29% of intervals

during baseline to 74% of intervals during the token economy condition, the researchers

were disappointed to see the study behaviors did not generalize to times of the day in

13

which the token economy was not implemented. Therefore, the researchers implemented

a combination condition in which students were able to earn the points contingent on

appropriate study behaviors but could also lose those points contingent on problem

behaviors. After the introduction of this condition, appropriate study behavior increased

to an average of 80% of intervals throughout the entire day indicating greater

generalization for the combination condition.

A study conducted in 1972 by Kaufman and O’Leary showed it was possible to

increase reading behavior and task engagement using both a response cost condition and

a token economy condition among 16 students living in a psychiatric hospital. Their

study indicated that while both were effective in increasing reading and task engagement

skills, there was not a significant difference between the two conditions.

Iwata and Bailey (1974) compared the effectiveness of a token economy and

response cost condition on student’s academic and social behaviors among 15 students in

a special education classroom. The students were divided into two different groups and

each group experienced both the token economy and response cost conditions throughout

the study. Results showed that the average number of problem completed by students

during the token economy and response cost conditions showed a slight increase

compared to baseline rates, accuracy remained similar throughout the entire study, and

off task behavior reduced significantly for both conditions compared to baseline. This

study also assessed whether or not students preferred one condition over the other.

Therefore, the last phase of the study involved the students being allowed to pick if they

participated in a response cost condition or a token economy condition. Results showed

14

there was no significant pattern of preference between the two conditions. In fact, four

students consistently chose the token economy system, five students consistently chose

the response cost condition, and the remaining six students switched back and forth

between the two conditions.

Other studies have assessed teacher, parent, and student preference for response

conditions and token economy systems. In general, techniques that focus on increasing

positive behaviors have been rated higher and as more acceptable compared to techniques

that have focused on reducing negative behaviors with the exception of response cost

techniques (Frentz, & Kelley, 1986). Little and Kelley (1989) assessed treatment

acceptability for five different parenting techniques: response cost, rewards for good

behavior, timeout with spanking, spanking alone, and timeout alone. Results indicated

parents rated response cost as the most acceptable and it was rated high on the Parent’s

Consumer Satisfaction Questionnaire. Reynolds and Kelley (1997) assessed treatment

acceptability of a response cost procedure using the Intervention Rating Profile – 15 and

a 6-point Likert scale. Results showed prior to treatment the teachers had rated response

cost as a favorable classroom management technique. After the teacher’s employed a

response cost procedure in their classroom, their ratings increased and teachers rated it as

a highly acceptable treatment. A study conducted in 1998 examined the treatment

acceptability among mothers who have children who exhibit disruptive and problem

behaviors. The techniques assessed included: differential attention, over-correction,

positive reinforcement, response cost, spanking, and time-out. The conclusion of the

study showed mothers rated positive reinforcement the highest followed by response cost

15

and time out. Differential attention, overcorrection, and spanking were rated the lowest

by mothers (Jones, Eyberg, Adams, & Boggs, 1998). A similar study conducted in 2007

showed similar results in which response cost, token economy, and time out were rated as

the most acceptable and overcorrection, ignoring, and differential attention were rated

lower (Pemberton, & Borrego, 2007). McGoey and DuPaul (2000) noted that teachers

found the response cost condition to be more acceptable and chose to implement it within

their classroom during the choice condition.

Florida Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted in the spring of 2012. The school was located in a

small suburb of Orlando Florida in a low socioeconomic neighborhood. The majority of

the students were bilingual speaking English and Spanish. The majority of the parents

spoke Spanish and only two parents had received an education higher than High School.

The teacher had been referred for the study due to behavior problems in her classroom.

The teacher, Mrs. C, was a certified fourth grade teacher who had five years of teaching

experience. The subjects in the study included 22 children in a fourth grade general

education classroom. The classroom included 14 boys and 8 girls with an average age of

9 years old. Three students were not included in the study, one student was on an IEP that

included an individualized token economy system that the team did not want changed, a

second student’s parents did not provide consent for their child to participate, and a third

student entered the classroom half way through the study. Therefore, a total of 19

students participated in the study. Using methods identical to the current study, the data

showed contrasting results to the earlier studies conducted.

16

In the pilot study, data showed an increase in academic engagement during the

Combination and Token Economy conditions and lower levels of academic engagement

during baseline and Response Cost conditions. Lower rates of disruptive/problematic

behavior was observed during the Combination and Token Economy conditions

compared to the baseline and Response Cost conditions. With regards to Academic

Understanding, the highest understanding occurred during the Combination condition.

Data from the student survey shows students favorite conditions were the Token

Economy and Combination conditions, their least favorite conditions were baseline and

Response Cost, the condition that made it easiest to learn was the Combination condition,

the condition in which learning was rated as the hardest were the Response Cost and

baseline conditions, and students preferred to continue the Combination condition in the

future. Data from the teacher survey shows Ms. C preferred the Token Economy and

Combination conditions, she reported students appeared more anxious and problem

behaviors were higher during baseline and Response Cost, and she will be administering

Token Economy or the Combination strategy in the future.

Some limitations to the pilot study included the small sample size of only one

class with one teacher who was in charge of teaching the class and delivering tokens

during each condition. Therefore, the strategies were not administered as rigorously as if

multiple adults were in the classroom. Lastly, the classroom was video recorded making

observing students difficult at times if they walked out of view of the camera. Future

research is important to clarify which classroom management strategy is the most

beneficial for increasing student academic engagement and performance as well as the

17

most efficient for reducing problematic behavior in the classroom. Most of the studies

showing Response Cost as being just as effective if not more effective were conducted in

the 1970s and 1980s. The demographics of our students have changed since then,

therefore creating a need to validate current classroom management strategies commonly

used among teachers.

Purpose of the Current Study

The purpose of the present study is to update the literature as well as compare the

effectiveness of three classroom management strategies; response cost, token economy,

and combination of response cost and token economy. The study will assess the ability

of the three conditions to reduce problem behaviors, increase academic engaged time,

increase academic performance, and identify teacher and student preference.

Additionally, the study was designed to enhance the research showing support for token

economy systems as an empirically based behavior management intervention for both

individuals and classrooms in the school setting and to meet the methodological features

of single-case design studies set for by Kratochwil and colleagues (2002; 2010). These

five features include: 1. Operational definitions if all variables and settings, 2.

Replication of effects, 3. Collection of treatment integrity data, 4. Collection of

interobserver agreement/reliability data, and 5. Collection of social validity data. It is

hypothesized that both the Token Economy and Combination conditions will result in

higher academic engagement rates and lower problem behavior rates compared to

Response Cost and Baseline conditions. Additionally, it is hypothesized that students will

have higher academic performance in the Token Economy and Combination conditions

18

compared to the Response Cost and Baseline conditions. Furthermore, it is hypothesized

that both students and teachers will report preferring Token Economy and Combination

conditions over Response Cost and Baseline conditions.

19

CHAPTER II

METHODS

Participants

The subjects in the current study included two first grade classrooms in an

elementary school located in a small town in West-Central Wisconsin. The teachers were

referred for the study due to behavior problems in the classroom that required the teacher

to stop their instruction or class activity at least three times on average per lesson. In the

first classroom, the teacher was a veteran with more than 20 years experience at the

elementary level (teacher C.S.). This classroom had 16 students total during Math class

with one student receiving special education support during instruction for emotional and

behavioral needs. In the second classroom, the teacher was a newer teacher with less than

three years experience at the elementary level (teacher S.M.). This classroom had 14

students total during Math class with one student receiving special education support as

needed for emotional and behavioral needs and two students receiving academic support

through English as a Second Language instruction as needed during independent

seatwork.

Students in C.S. classroom were between 80-95 months old with an average age

of 86.3 months old. Ninety-four percent of the students were Caucasian and 1% of the

students were Hispanic. Students in S.M. classroom were between 80-92 months old with

an average age of 85.71 months old. Sixty-nine percent of the students were Caucasian,

30% were African American, and 1% was Asian.

20

Dependent Measures

Data on problem behaviors were collected via frequency counts from directly

observing the classroom each day. Problem behavior was defined as exhibiting any

behaviors or audible vocalizations that were disruptive, interfered with learning, or

impeded instructional delivery. Specific examples include fidgeting, drawing on self,

talking out, and disruptive interaction with peers that interfered with learning, leaving the

assigned instructional area, and making audible vocalizations not related to the

instructional task such as singing, humming, or talking back.

Data on academic engaged time was collected via momentary time sampling with

15 second intervals from directly observing the classroom each day. Observers recorded

each student in a systematic order for a total of 25 minutes. Academic engagement was

defined as the student looking at materials, raising hand, working on tasks that the teacher

specified, and/or engaged in communication with peers or teacher that is relevant to the

task at hand.

Data on academic performance was collected through analyzing the permanent

product of a three question quiz each student completed at the end of each math lesson.

The quiz included either multiple choice or true/false questions covering the material

from the current lesson and was developed by the teacher prior to the start of the lesson.

Student and teacher preference was assessed at the end of the study by asking

both the teachers and the students questions about the different conditions. Students were

individually interviewed and asked which was their favorite condition and why, least

favorite condition and why, and which condition they would like their teacher to

21

implement next week. Teachers were sent an email with questions asking them which

procedure they liked administering best and why, which procedure they liked

administering least and why, if they noticed their students behaving better or

academically engaged more during any of the conditions, if they noticed their students

misbehaving more or academically engaged less during any of the conditions, what they

liked about the different strategies, what they did not like about the different strategies,

what were some advantages to the different strategies you used, what were some of the

disadvantages to the different strategies you used, if you could make any changes what

would they be, which one would you be most likely to do in the future and why, which

one would you be least likely to do in the future and why.

Independent Measures

The independent measures of the current study were the different classroom

management strategies employed by the teacher. An alternating treatments design was

used throughout two phases. During the first phase, the teacher alternated between all

four conditions; the baseline condition, response cost condition, token economy

condition, and combination condition each day throughout the week for four weeks. The

order was randomly assigned to control for any history and sequence effects. During the

second phase, the teacher alternated between the two conditions found to be the most

effective at reducing problem behaviors and increasing academic engagement in their

classroom during the first phase. The order of the two conditions was randomly assigned

to control for any history and sequence effects. The study concluded with each teacher

22

employing the classroom management strategy that was the most effective at reducing

problem behaviors and increasing academic performance in their classroom.

Procedure

Pre-Baseline. Prior to data collection, the researcher gained IRB approval for the

study and located two teachers interested in participating in the study. The researcher and

teachers discussed what they considered to be academically engaged as well as

operationally defined the problem behaviors they had witnessed in their classrooms.

Along with IRB approval and teacher approval, the researcher also obtained consent from

the superintendent, school principal, and each student’s parents.

Baseline. During baseline, the teacher started the lesson by giving the students the

following instructions, “During today’s math lesson, you will not be given any tokens nor

will you be able to lose any tokens. I still want you all to be on your best behavior.” The

teacher then taught the lesson as normal, without delivering any type of tangible

reinforcement contingent on behavior. At the end of the lesson, the teacher transitioned

the kids to the next activity since there were no tokens for students to exchange.

Token Economy. During this condition, the teacher started the lesson by giving

the students the following instructions, “During today’s math lesson, you will have the

opportunity to earn a token for “good” behavior. When you earn a token, I will place it

in your name slot on the wall or name card located at your desk depending on where we

are in the classroom. Your tokens cannot be taken away right now, you can only earn

them for good behavior. At the end of the lesson you can exchange your tokens for either

a hand stamp or piece of candy from the reward box.” The teacher then started the lesson

23

as normal and delivered tokens to students contingent upon desirable behavior. When

delivering a token, the teacher briefly stated what behavior the student was earning the

token for (e.g., “I like the way you are reading quietly in your seat.”). The teacher

continued to deliver tokens throughout the math lesson for the day. At the end of the

lesson, the teacher allowed students to exchange their tokens. The magnitude and size of

the reinforcer was determined by the number of tokens the student had earned to

exchange.

Response Cost. During this condition, the teacher started out the lesson by giving

the students the following instructions, “During today’s math lesson, each of you will be

given five tokens in your name slot on the wall or name card located on your desk

depending on where we are in the classroom. Each time you misbehave, I will come and

take a token away. You cannot earn tokens back today; you can only keep them if you do

not engage in any problem behaviors and follow classroom expectations and rules. At the

end of the lesson you can exchange whatever tokens you have left for hand stamps or

candy in the reward box.” The teacher then gave each student five tokens and started the

lesson as normal. Throughout the lesson, anytime a student engaged in

problem/disruptive behavior (as identified in the problem behavior definition list) the

teacher went over to the student and quietly took away a token from their name slot or

card and told the student why the token was being taken away (e.g. “I do not like the way

you are twirling your book, instead you should be reading chapter 4.”). The teacher

continued to take away tokens throughout the math lesson contingent on problem

behaviors. At the end of the lesson, the teacher allowed students to exchange whatever

24

tokens they had left. The magnitude and size of the reinforcer was determined by the

number of tokens the student had left to exchange.

Combination Condition. During this condition, the teacher started out the lesson

by giving the students the following instructions, “During today’s math lesson, you will

have the opportunity to earn tokens for “good” behavior. When you earn a token, I will

place it in your name slot on the wall or name card located on your desk depending

where we are in the classroom. Your tokens can be taken away if you engage in any

problem behaviors. So throughout math today, you can earn tokens for good behavior

AND you can get your tokens taken away for bad behavior. At the end of the lesson you

can exchange however many tokens you have for hand stamps and/or pieces of candy in

the reward box.” The teacher then started the lesson as normal and delivered a to students

contingent on good behavior with a brief, quiet description of what behavior the student

was earning the token for (e.g. “I like the way you are reading quietly in your seat.”) and

took away tokens contingent on inappropriate behavior with a brief, quiet description of

what behavior the student was getting the token taken away for (e.g., “I do not like the

way you are singing and looking around instead of reading your book.”). The teacher

continued to deliver and take away tokens throughout the math lesson. At the end of the

math lesson, the teacher allowed students to exchange their tokens. The magnitude and

size of the reinforcer were determined by the number of tokens the student had left to

exchange.

Token Exchange. The tokens students earned were exchanged at the end of each

math lesson. Students were not able to keep the tokens or save them across sessions to

25

control for the effects of saving tokens for larger reinforcers at a later time. Students who

had 5 or more tokens at the end of math class exchanged them for three items, students

who had 3 or 4 tokens exchanged them for 2 items, students who had 1 or 2 tokens

exchanged them for 1 item, and students who did not have any tokens at the end of the

math lesson were unable to receive any items. Items consisted of a hand stamp or a piece

of candy from the reward box. Students had the option of two different hand stamps that

were switched out on a weekly basis. Adults throughout the school are aware that

students earn stamps on their hand for positive/good behavior and often ask students

about the stamps and provide positive social praise. Additionally, students are

encouraged to go home and tell their parents what they did to earn a hand stamp. Students

had the option of many different pieces of candy from small suckers to soft pieces of

candy such as Starbursts to hard pieces of candy such as Jolly Ranchers. Students were

not able to eat the candy in school, they had to put the candy in their mailbox to go home

with them at the end of the day. If a student had 5 or more tokens at the end of math

class, they could pick three items; therefore, they could pick three hand stamps, or three

pieces of candy, or two hand stamps and one pieces of candy, or two pieces of candy and

one hand stamp. Choice of backup reinforcers was a focus in the study to reduce satiation

and maintain the reinforcing efficacy of the tokens.

Data Analysis. The data collected for this study was visually analyzed on a

weekly basis to check for student performance and effectiveness of the different

management strategies. Visual analysis was also used to determine which two strategies

were most effective at reducing problem behaviors and increasing academic engagement

26

in each classroom for implementation during phase two and which was the most effective

for implementation during the final phase.

Inter-Rater Reliability. Inter-rater reliability was collected and analyzed on 33%

of sessions. Inter-rater reliability was collected on problem behavior occurrences in the

classroom, academic engagement among students in the classroom, academic

performance scoring of the three question quiz, and treatment fidelity.

Treatment Integrity. Treatment integrity was assessed by recording the number

of steps in each classroom management strategy the teacher successfully carried out such

as correctly reading the instructions to the class at the beginning of each math lesson

dependent on the condition for the day, delivering/removing tokens contingent on student

behavior dependent on the condition for the day, allowing students to exchange tokens at

the appropriate rate at the end of each math lesson, and ensuring each student took a

teacher developed 3 question objective quiz at the end of each math lesson. The number

of steps the teacher missed was subtracted from the number of total steps that should

have been completed and divided to determine the percentage of steps accurately

completed. This was conducted for 100% of the math lessons and analyzed daily. If the

teacher reached the minimum criterion of 100% of steps successfully completed she was

given positive verbal attention and praise, if the teacher missed one or more of the steps

she was sent an email with the steps she missed and a meeting would have been

scheduled to further discuss the steps missed and conduct a booster training session.

27

CHAPTER III

RESULTS

Academic Engagement

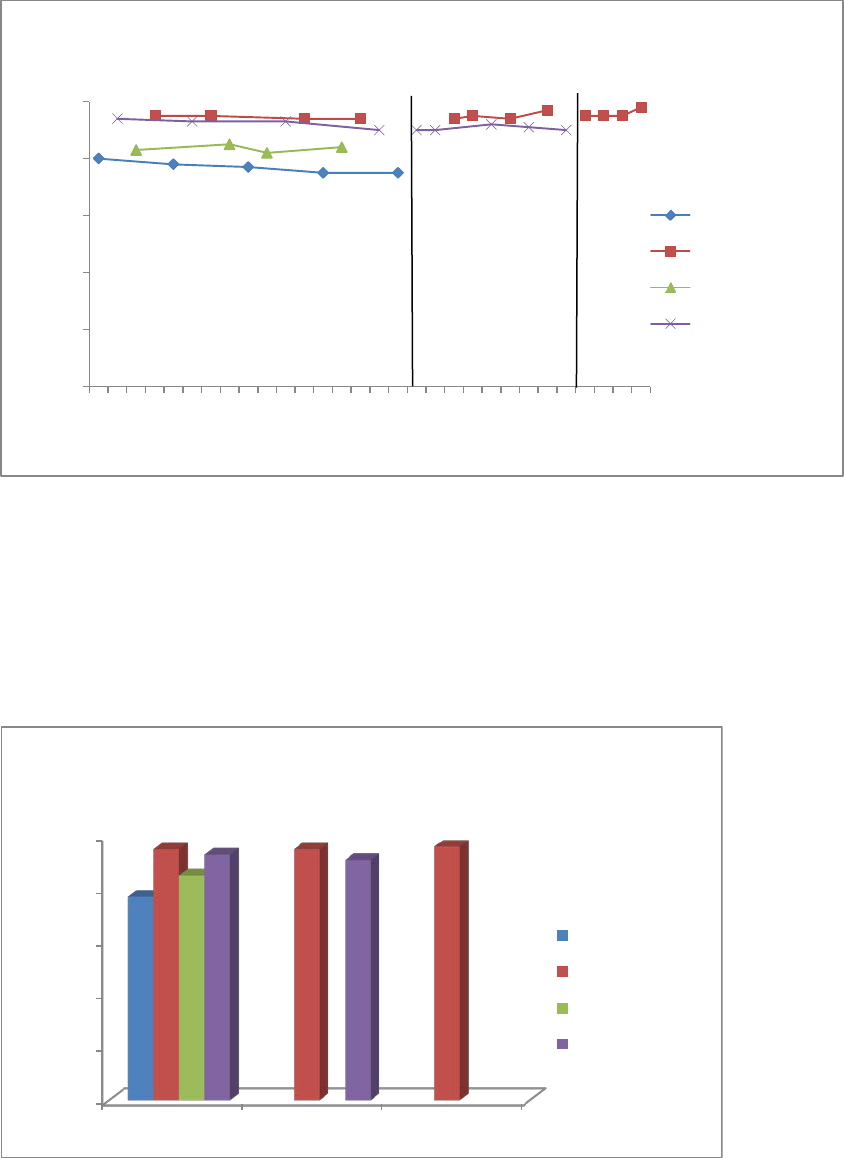

Results from the study show both Token Economy and Combination conditions

were more effective at increasing student engagement during math for both classrooms.

As can be seen from figure 1, student academic engagement during Math lessons for

classroom C.S. was higher during both the Token Economy and Combination conditions

compared to the Response Cost and Baseline conditions during Phase 1. Students were

academically engaged between 75% and 80% of the time with an average of 77% of the

time academically engaged during baseline, 94% - 95% of the time with an average of

95% of the time academically engaged during Token Economy, 82% - 85% of the time

with an average of 85% of the time academically engaged during Response Cost, and

90% - 94% of the time with an average of 93% of the time academically engaged during

the Combination condition throughout Phase 1 (see figure 2). Results from the second

phase of the study showed Token Economy was slightly better at increasing student

engagement during math compared to the Combination condition for C.S. classroom.

Students were academically engaged between 94% - 97% of the time with an average of

95% of the time during Token Economy compared to 90% - 92% of the time with an

average of 91% of the time academically engaged during the Combination conditions.

The final phase of the study consisted of only the Token Economy condition in which

students were academically engaged between 95% - 98% of the time with an average of

96% of the time (see figures 1 & 2).

28

Figure 1. Percent of intervals students were academically engaged in C.S.’ classroom

during the Token Economy, Response Cost, Combination, and Baseline conditions across

the three phases.

.

0

20

40

60

80

100

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29

Percentage of Intervals Academically

Engaged

Session

Academic Engagement - Classroom CS

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

Phase

Phase Two

Phase Three

0

20

40

60

80

100

Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

Percentage of Intervals Academically

Engaged

Average Academic Engagement by

Condition and Phase - C.S.

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

29

Figure 2. The average percentage of intervals students were academically engaged by

condition across the three phases for C.S.’ classroom.

As can be seen from figure 3, student academic engagement during Math lessons

for classroom S.M. was higher during both Token Economy and Combination conditions

compared to the Response Cost and Baseline conditions during phase 1. Students were

academically engaged between 73% - 80% during Baseline with an average of 76%

academically engaged, between 89% - 94% during Token Economy with an average of

93% academically engaged, between 79% - 84% during Response Cost with an average

of 81% academically engaged, and between 90% - 94% during the Combination

condition with an average of 91% academically engaged during phase 1 (see figures 1 &

2). Results from the second phase of the study showed Token Economy was slightly

better at increasing student engagement during math compared to the Combination

condition for S.M. classroom. Students were academically engaged between 94% - 96%

of the time during Token Economy with an average of 95% of the time and between 88%

- 91% of the time during the Combination condition with an average of 90% of the time

academically engaged. The final phase of the study consisted of only the Token Economy

condition in which students were academically engaged between 93% - 97% of the time

with an average of 96% of the time (see figures 1 & 2).

30

Figure 3. Percent of intervals students were academically engaged in S.M.’s classroom

during the Token Economy, Response Cost, Combination, and Baseline conditions across

the three phases.

Figure 4. The average percentage of intervals students were academically engaged by

condition across the three phases for S.M.’s classroom.

0

20

40

60

80

100

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

Percentage of Intervals Academically Engaged

Session

Academic Engagement - Classroom SM

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

Phase One

Phase Two

Phase Three

0

20

40

60

80

100

Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

Percentage of Intervals Academically

Engaged

Average Academic Engagement by

Condition and Phase - S.M.

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

31

Table 1

Percentage of Non-Overlapping Data Points Among Conditions for Academic

Engagement by Classroom

Academic

Engagement

Classroom:

Condition(s)

Compared to:

Effect Size

Descriptor

C.S.

Token Economy,

Combination,

Response Cost

Baseline

100%

Highly

Effective

Combination, Token

Economy

Response Cost

100%

Highly

Effective

Response Cost

Baseline

100%

Highly

Effective

Token Economy Combination

Phase 1 =

25%

Phase 2 =

100%

Phase 1 =

Ineffective

Phase 2 =

Highly

Effective

S.M.

Token Economy,

Combination,

Response Cost

Baseline

100%

Highly

Effective

Combination, Token

Economy

Response Cost

100%

Highly

Effective

Response Cost

Baseline

100%

Highly

Effective

Token Economy

Combination

Phase 1 =

0%

Phase 2 =

100%

Phase 1 =

Ineffective

Phase 2 =

Highly

Effective

Table 1 shows that all three conditions, Token Economy, Combination, and Response

Cost were highly effective compared to the Baseline condition at increasing academic

32

engagement in both classrooms. Additionally, Token Economy and Combination

conditions were Highly Effective compared to the Response Cost condition at increasing

academic engagement in both classrooms. Lastly, Token Economy was not more

effective compared to the Combination condition at increasing academic engagement

during the first phase for either classroom, however, during the second phase, Token

Economy was highly effective at increasing academic engagement compared to the

Combination condition.

Disruptive Behavior

Results from the study show both Token Economy and Combination conditions

were more effective at decreasing the rate of disruptive behaviors during math for both

classrooms compared to the Response Cost and Baseline conditions during phase 1. As

can be seen from figures 5 and 6, the rate of disruptive behavior for C.S. classroom

ranged from .92 – 1.2 behaviors per minute during the baseline condition with an average

of 1.04 behaviors per minute. During the Token Economy condition, disruptive behavior

ranged from .16 - .32 behaviors per minute with an average of .22 behaviors per minute.

During the Response Cost condition, disruptive behavior ranged from .52 - .88 behaviors

per minute with an average of .72 behaviors per minute. During the Combination

condition, disruptive behavior ranged from .12 - .4 behaviors per minute with an average

of .15 behaviors per minute. Results from the second phase of the study show that Token

Economy was slightly better at decreasing the rate of disruptive behavior for C.S.

classroom compared to the Combination condition. According to figures 5 and 6,

disruptive behavior ranged from .12 - .2 behaviors per minute during Token Economy

33

with an average of .15 behaviors per minute compared to .24 - .32 disruptive behaviors

per minute during Combination with an average of .28 behaviors per minute. The final

phase of the study consisted of the Token Economy condition for C.S. classroom.

Disruptive behaviors ranged from .12 - .13 behaviors per minute with an average of .13

behaviors per minute.

Figure 5. Rate of disruptive student behaviors per minute during the Token Economy,

Response Cost, Combination, and Baseline conditions for C.S.’ classroom across the

three phases.

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

Disruptive Behaviors per Minute

Session

Disruptive Behaviors

- Classroom CS

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

Phase One

Phase Two

Phase Three

34

Figure 6. Average rate of disruptive student behaviors per minute by condition across the

three conditions for C.S.’ classroom.

As can be seen from figures 7 and 8, the rate of disruptive behavior for S.M.

classroom ranged from 1 – 1.24 behaviors per minute during baseline with an average of

1.12 behaviors per minute during phase 1. During the Token Economy condition,

disruptive behavior ranged from .16 - .28 behaviors per minute with an average of .21

behaviors per minute. During the Response Cost condition, disruptive behavior ranged

from .6 – 1.08 behaviors per minute with an average of .8 behaviors per minute and

during the Combination condition, disruptive behavior ranged from .24 - .52 behaviors

per minute with an average of .35 behaviors per minute. During the second phase of the

study, results showed that Token Economy was slightly better at reducing the rate of

disruptive behavior among students during math compared to the Combination condition.

According to figures 7 and 8, the rate of disruptive behaviors ranged from .16 - .24

behaviors per minute during Token Economy with an average of .19 behaviors per

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

Disruptive Behaviors per Minute

Average Disruptive Behaviors by

Condition and Phase

- C.S.

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

35

minute while the rate of disruptive behaviors ranged from .27 - .36 behaviors per minute

for Combination with an average of .3 behaviors per minute. The final phase of the study

consisted of the Token Economy condition for S.M. classroom. Disruptive behaviors

ranged from .12 - .26 behaviors per minute with an average of .16 behaviors per minute.

Figure 7. Rate of disruptive student behaviors per minute during the Token Economy,

Response Cost, Combination, and Baseline conditions for S.M.’s classroom across the

three phases.

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

24 25 26 27 28

29 30

Disruptive Behaviors per Minute

Session

Disruptive Behaviors

- Classroom SM

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

Phase One

Phase Two

Phase Three

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

Disruptive Behaviors per Minute

Average Disruptive Behaviors by

Condition and Phase - S.M.

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

36

Figure 8. Average rate of disruptive student behaviors per minute by condition across the

three conditions for S.M.’s classroom.

Table 2

Percentage of Non-Overlapping Data Points Among Conditions for Disruptive Behavior

by Classroom

Disruptive Behavior

Classroom:

Condition(s)

Compared to:

Effect Size

Descriptor

C.S.

Token Economy,

Combination,

Response Cost

Baseline

100%

Highly

Effective

Combination, Token

Economy

Response Cost

100%

Highly

Effective

Response Cost

Baseline

100%

Highly

Effective

Token Economy Combination

Phase 1 =

0%

Phase 2 =

100%

Phase 1 =

Ineffective

Phase 2 =

Highly

Effective

S.M.

Token Economy,

Combination,

Response Cost

Baseline

94%

Highly

Effective

Combination, Token

Economy

Response Cost

100%

Highly

Effective

Response Cost

Baseline

89%

Moderately

Effective

Token Economy Combination

Phase 1 =

88%

Phase 2 =

100%

Phase 1 =

Moderately

Effective

Phase 2 =

Highly

Effective

37

Table 2 shows that all three conditions, Token Economy, Combination, and Response

Cost were highly effective compared to the Baseline condition at decreasing problem

behaviors in both classrooms. Token Economy and Combination conditions were Highly

Effective compared to the Response Cost condition at decreasing problem behaviors in

both classrooms. Response Cost condition was highly effective at reducing problem

behaviors compared to the Baseline condition in C.S. classroom but was only moderately

effective in S.M. classroom. Lastly, when looking at Token Economy compared to the

Combination condition, there was no difference during phase 1 in C.S. classroom,

however during phase 2 Token Economy was highly effective. For S.M. classroom,

during phase 1 Token Economy was moderately effective and during phase 2, Token

Economy was highly effective compared to the Combination condition.

Academic Performance

Results from the study show that, on average, Baseline and Token Economy

conditions were slightly better at increasing Academic Performance compared to

Response Cost and the Combination conditions for C.S. classroom (see figure 10).

During phase 1, academic performance ranged from 1.78 points to 2.91 points during

Baseline with an average of 2.37 points. During Token Economy, academic performance

ranged from 1.88 points to 2.81 points with an average of 2.35 points. During Response

Cost, academic performance ranged from 1.93 points to 2.62 points with an average of

2.22 points and during the Combination condition, academic performance ranged from

1.81 points to 2.27 points with an average of 1.99 points. During the second phase of the

study, Token Economy resulted in slightly higher Academic Performance scores

38

compared to the Combination condition with a range of 2.27 to 2.31 points (average = 2.3

points) compared to a range of 1.75 to 2.53 points (average = 2.1 points). During the final

phase of the study, only the Token Economy condition was delivered and academic

performance ranged from 1.84 – 2.8 points with an average of 2.32 points (see figures 9

& 10).

Figure 9. Academic performance as measured by average class points earned on a three

point quiz given to students daily during the Token Economy, Response Cost,

Combination, and Baseline conditions across the three phases for C.S.’ classroom.

0

0.25

0.5

0.75

1

1.25

1.5

1.75

2

2.25

2.5

2.75

3

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 101112131415161718192021222324252627282930

Average Points Earned by Class

Session

Academic Performance - C.S.

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

Phase One

Phase Two

Phase Three

39

Figure 10. Average academic performance as measured by average points earned on daily

three point quiz by condition across the three phases in C.S.’ classroom.

Results from the study show that, on average, Token Economy and Response Cost

conditions were slightly better at increasing academic performance compared to the

Baseline and Combination conditions during phase 1 for S.M. classroom (see figure 12).

During phase 1, academic performance ranged from 2.2 points to 2.82 points during

Baseline with an average of 2.43 points. During Token Economy, academic performance

ranged from 2.36 points to 2. 85 points with an average of 2.59 points. During the

Response Cost condition, academic performance ranged from 2.28 points to 2.93 points

with an average of 2. 6 points and during the Combination condition academic

performance ranged from 2.07 points to 2.39 points with an average of 2.29 points.

During the second phase of the study, Token Economy resulted in slightly higher

academic performance scores compared to the Combination condition with a range of

2.31 – 2.69 points (average = 2.59 points) compared to a range of 2.31 – 2.85 points

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

Average Points Earned

Average Academic Performance by Condition

and Phase

- C.S.

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

40

(average = 2.51 points). During the final phase of the study, only the Token Economy

condition was delivered and academic performance ranged from 2.58 – 2.91 points with

an average of 2.78 points (see figures 11 & 12).

Figure 11. Academic performance as measured by average class points earned on a three

point quiz given to students daily during the Token Economy, Response Cost,

Combination, and Baseline conditions across the three phases for S.M.’s classroom.

.

0

0.25

0.5

0.75

1

1.25

1.5

1.75

2

2.25

2.5

2.75

3

1

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10111213

14151617

181920212223242526272829

30

Average Points Earned by Class

Session

Academic Performance

- S.M.

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

Phase One

Phase Two

Phase Three

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3

Average Points Earned

Average Academic Performance by Condition

and Phase - S.M.

Baseline

Token Economy

Response Cost

Combination

41

Figure 12. Average academic performance as measured by average points earned on daily

three point quiz by condition across the three phases in S.M.’s classroom.

Table 3

Percentage of Non-Overlapping Data Points among Conditions for Academic

Performance by Classroom

Academic

Performance

Classroom:

Condition(s)

Compared to:

Effect Size

Descriptor

C.S.

Token Economy,

Combination,

Response Cost

Baseline

0%

Ineffective

Combination, Token

Economy

Response Cost

17%

Ineffective

Response Cost

Baseline

0%

Ineffective

Token Economy Combination

Phase 1 =

25%

Phase 2 =

0%

Phase 1 =

Ineffective

Phase 2 =

Ineffective

S.M.

Token Economy,

Combination,

Response Cost

Baseline

12%

Ineffective

Combination, Token

Economy

Response Cost

0%

Ineffective

Response Cost

Baseline

11%

Ineffective

Token Economy Combination

Phase 1 =

25%

Phase 2 =

0%

Phase 1 =

Ineffective

Phase 2 =

Ineffective

42

Table 3 shows that none of the conditions, Token Economy, Combination, Response Cost

or Baseline were moderately or highly effective at increasing academic performance in

either classroom.

Student Preference

Results from the individual student interviews for C.S. classroom showed that

students favorite condition was Token Economy (n = 11) followed by Combination (n =

3), Response Cost (n = 1), and Baseline (n = 0). Students least favorite condition was

Response Cost (n = 8) followed by Baseline (n = 5), Token Economy (n = 1), and

Combination (n = 1). The condition most students wanted their teacher to implement in

the future was Combination (n = 8) followed by Token Economy (n = 6), Baseline (n =

1), and Response Cost (n = 0). One student was absent the day of the individual

interviews.

Results from the individual student interviews for S.M. classroom showed that

students favorite conditions were Combination (n = 6) and Token Economy (n = 6)

followed by Response Cost (n = 0), and Baseline (n = 0). Students least favorite condition

was Baseline (n = 7) followed by Response Cost (n = 4), Token Economy (n = 1), and

Combination (n = 0). One student was not sure which condition was their least favorite

and did not provide an answer to this question. The condition most students wanted their

teacher to implement in the future was Combination (n = 6) followed by Token Economy