For most men

the fact of

fatherhood

results in

a wage

bonus; for

most women

motherhood

results in a

wage penalty.

WHAT’S NEXT?

For the past forty years at least, progressive advocates have been

concerned about the status of working women in American society. At

the center of that issue has been the persistence of the “wage gap”—

the dierence between men’s and women’s earnings. Certainly progress

has been made. In 1979, as the rst large generation of feminists were

making their way into the work force, women made 63 cents for every

dollar men made. By the turn of the century, however, that gap had

closed to 81 cents on the dollar and for certain selected sub populations,

unmarried, childless women in urban areas, women were making more

money than men. Overall, never married women in 2012 had almost

closed the wage gap—earning 96% of what men earn. So why are we

still concerned about the wage gap? Is this issue over?

Michelle J. Budig, a professor at the University of Massachusetts-

Amherst, claries this debate by looking at the wage gap in terms of

the one thing that the majority of adults experience in their lifetime—

parenthood. In a new and provocative paper, Budig looks at fathers and

mothers. For most men the fact of fatherhood results in a wage bonus;

for most women motherhood results in a wage penalty. “While the

gender pay gap has been decreasing, the pay gap related to parenthood

is increasing,” says Budig.

e persistence of the wage gap occurs because the fatherhood

bonus and the motherhood penalty are not evenly distributed

across all income and social class levels. Using a sophisticated

statistical technique on a large sample of American workers, Budig

controls for a variety of variables that could produce a gap between

fathers and non-fathers. Her conclusion is that the fatherhood

“bonus” is not equal across the income distribution; in fact it is

much greater for men at the top. “Fatherhood,” she concludes, “is

a valued characteristic of employers, signaling perhaps greater work

commitment, stability, and deservingness.”

e opposite pattern emerges when Budig turns her attention to the

eects of motherhood on women’s wages. Each child costs women.

But as with the fatherhood bonus the motherhood penalty is not

evenly distributed across income levels. In fact, at the very top of the

income distribution for women, there is no motherhood penalty at

all. But at the bottom of the wage distribution, low income women

bear a signicant and costly motherhood penalty. In other words,

“the women who least can aord it, pay the largest proportionate

penalty for motherhood.”

Understanding the nuances of this report is critical to social policy. e

fact that low income women bear a substantial motherhood penalty

that is not oset by a fatherhood bonus among low income men

means that simple xes such as encouraging marriage are not likely to

solve the problem. And given that people tend to marry people who

are similar to them, these eects are likely to exacerbate inequality.

Budig’s paper, “e Fatherhood Bonus and the Motherhood Penalty:

Parenthood and the Gender Gap in Pay” is the latest in a series of

ahead-of-the-curve, groundbreaking pieces published through ird

Way’s NEXT initiative. NEXT is made up of in-depth, commissioned

academic research papers that look at trends that will shape policy over

the coming decades. In particular, we are aiming to unpack some of

the prevailing assumptions that routinely dene, and often constrain,

Democratic and progressive economic and social policy debates.

In this series we seek to answer the central domestic policy challenge

of the 21st century: how to ensure American middle class prosperity

and individual success in an era of ever-intensifying globalization and

technological upheaval. It’s the dening question of our time, and one

that as a country we’re far from answering.

Each paper dives into one aspect of middle class prosperity—such as

education, retirement, achievement, or the safety net. Our aim is to

challenge, and ultimately change, some of the prevailing assumptions

that routinely dene, and often constrain, Democratic and progressive

economic and social policy debates. And by doing that, we’ll be

able to help push the conversation towards a new, more modern

understanding of America’s middle class challenges—and spur fresh

ideas for a new era.

Jonathan Cowan

President, ird Way

Dr. Elaine C. Kamarck

Resident Scholar, ird Way

Our aim is to

challenge,

and ultimately

change,

some of the

prevailing

assumptions

that routinely

define, and

often constrain,

Democratic and

progressive

economic and

social policy

debates.

I

n September of 2010, ABC World News trumpeted a reversal of the gender

pay gap, stating that women were now out-earning men.

1

Analyzing Census

data, Reach Advisors, a market research rm, showed that women earn 8%

more than their male counterparts. However, this reversal applied only to a very

select group of women: unmarried, childless women under 30 years old who live

in urban areas. You’ve come a long way baby? Not really.

While women have made progress vis-a-vis men in terms of employment

and earnings, the recent Bureau of Labor Statistics Report

2

reveals that

an overall gender gap in pay persists, such that among full-time workers,

women earned 81 cents on a man’s dollar in 2012. Progress has stalled

in the 21st century in reducing this inequality. Consider that in 1979

women earned 63 cents to a man’s dollar, and that this gap declined

every year until 2003, when it reached the current 81 cents level and

has remained there ever since. In past decades, between 1979-89, or

1989-99, the gender pay gap declined by 8 to 10 percentage points. Yet

in the most recent decade 2003-2013, the gender pay gap has declined

by 1 point. Figure 1 from the BLS report reveals this stall in progress.

What could be behind the gender pay gap stall of the last decade?

Are women generally behind men in earnings, or are certain groups

experiencing larger gender gaps? e BLS report shows that smaller

gender gaps exist among young workers, consistent with the ABC

News report. Figure 2 shows that among full-time workers, women

aged 25 to 34 years earn 90.2 cents on a man’s dollar, but this gap

widens precipitously among those aged 35 to 44 to 78 cents and

never recovers for any older age group. One possibility is that this is a

“cohort eect” wherein younger generations experience smaller gender

pay gaps and will maintain these smaller gaps over time (due to the

higher educational attainment and greater employment opportunities

of younger generations of women). However, the data more robustly

PARENTHOOD AND THE GENDER GAP IN PAY

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS &

THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY:

While women

have made

progress vis-

a-vis men

in terms of

employment

and earnings...

an overall

gender gap in

pay persists

6

THIRD WAY NEXT

Figure 1. Women’s Median Weekly Earnings as a Proportion of Men’s,

Full-time Wage and Salary Workers, 1979-2013

3

0.5

0.55

0.6

0.65

0.7

0.75

0.8

0.85

0.9

1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013

Figure 2. Women’s Median Weekly Earnings as a Percentage of Men’s

by Selected Characteristics, 2012

4

90%

78%

96%

77%

83%

76%

83%

50% 55% 60% 65% 70% 75% 80% 85% 90% 95% 100%

"

Age 25 to 34

"

Age 35 to 44

Never Married

Married

Formerly Married

Married Parent

Single Parent

7

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

support a second hypothesis—the “lifecycle eect” wherein the gender

pay gap widens within cohorts as they age and are exposed to processes

that aect earnings and thus increase the gender gap.

What life cycle events have happened by age 35 for modern Americans?

e answer is childbirth and marriage. While the period of age 35 to

44 is one when, in general, wages show the greatest lifetime gains, it is

also the same period when intensive family responsibilities, particularly

for mothers, are in full force. Especially for college educated women

in full-time jobs, who are more apt to delay motherhood, caring for

small children is intense in their mid-thirties. Among those in their

childbearing years (ages 15 to 44) in 2006-2010, 36% had their rst

birth after age 30, and an additional 41% had their rst birth between

the ages of 35 and 40.

5

Age at rst birth has risen for all educational

groups, and the time period of intensive childrearing is increasingly

concurrent with career-building years for American women. Gender

dierences in family responsibilities are linked to the gender pay gap.

Among full-time workers, marriage and children (under age 18) are

associated with higher earnings among men, but lower earnings among

women. e gure above shows the large dierences in earnings

between women and men of varying marital and parental statuses, as

reported by the BLS.

e comparisons of the gender pay gap by marital and parenthood

statuses are striking in the BLS data. e smallest gender pay gap

is found among unmarried men and women: Unmarried women

earn 96 cents to an unmarried man’s dollar, and childless women

(including married and unmarried) earn 93 cents on a childless man’s

dollar. In contrast, wives and mothers fare far less well. Even among

full-time workers, married mothers with at least one child under age

18 earn 76 cents on a married father’s dollar. Single mothers earn 83.1

cents to a single custodial father’s dollar (that single moms are much

less likely to be employed full-time relative to single dads is masked

by this estimate among full-time workers). ese gures show that

married mothers of minor children experience the largest wage gaps.

Marriage and motherhood are statuses that the majority of American

women experience at some point in the course of their lives. ough

age at rst marriage and age at rst birth are creeping upward, most

Americans eventually engage in parenthood. Despite men’s increased

participation in childcare, women, even full-time employed women,

still carry the lion’s share of domestic and child-related responsibilities.

6

Among full-

time workers,

marriage and

children are

associated with

higher earnings

among men,

but lower

earnings

among women.

8

THIRD WAY NEXT

Moreover, American workplaces have made few accommodations for

the needs of workers to balance family and work responsibilities.

e statistics reported thus far have shown only average dierences

between groups. But there are many reasons to expect that motherhood

should be associated with wage declines and that fatherhood should

be associated with wage gains. For example, mothers typically reduce

work hours, at least temporarily, following the birth of a child, while

men often increase hours after becoming fathers. If one can adjust for

these other factors, is there still an association between parenthood

status and earnings? Multivariate models and advanced statistical

methodologies are needed to answer this. I turn to ndings from

studies employing these methods next.

While causality is complex, there is a strong empirical association

between the gender gap (pay dierences between women and men)

and the family gap (pay dierences between individuals with and

without children).

7

Economist Jane Waldfogel’s research showed that

40 to 50 percent of the gender gap can be explained by the impact of

parental and marital status on men’s and women’s earnings. Moreover,

Waldfogel shows that while the gender pay gap has been decreasing,

the pay gap related to parenthood is increasing.

e eects of children on men’s and women’s earnings are referred to

as the fatherhood bonus and the motherhood penalty, respectively.

e fatherhood bonus is measured by comparing earnings of fathers

relative to childless men, taking into account dierences that might exist

between men with and without children. Similarly, the motherhood

penalty compares women with varying numbers of children (including

the childless) to see how children reduce earnings. My research into

the impact of parenthood on worker’s earnings suggests that gender

pay gaps widen with parenthood. e impact of parenthood plays

out dierently for men and women, and dierently by social class (as

marked by education, professional status, and earnings).

Generally, men nd that their earnings increase when they become

fathers, while each additional child is associated with earnings decline

for women. As I document below, in addition to generating gender

pay gaps between women and men, the eects of parenthood on

earnings vary in such a way as to exacerbate earnings inequalities

among low-income and high-income families. e fatherhood bonus

is highest for the most advantaged men—married white college

graduates with professional occupations involving cognitive skills.

Similarly, the motherhood penalty is the smallest among the most

The effects of

parenthood on

earnings vary in

such a way as

to exacerbate

earnings

inequalities

among low-

income and

high-income

families.

While the

gender pay

gap has been

decreasing, the

pay gap related

to parenthood

is increasing.

9

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

advantaged women—those earning above the 90th percentile among

women workers. Conversely, unmarried, African-American men in

non-professional occupations requiring few cognitive skills incur

the smallest fatherhood bonus, while women at the bottom of the

wage distribution incur the largest motherhood penalty. Since men

and women tend to marry those similar to themselves in terms of

education, race, and professional status, the combination of uneven

fatherhood bonuses and motherhood penalties implies increasing

inequality among heterosexual, two-parent households with children.

Below I present the detailed evidence of these phenomena.

DADDY BONUS: HOW FATHERHOOD RAISES

(MOST) MEN’S WAGES

How much more do men earn when they become fathers, relative to

being childless? is is the question central to the analysis presented

in Hodges and Budig.

8

Using the 1979-2006 waves of the National

Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), we investigated whether

and how the transition from childlessness to fatherhood impacts men’s

wages. Our key ndings are that, all else equal, fatherhood increases

men’s earnings by over 6%. Moreover, this daddy bonus is larger for

white men and Latinos, professional workers, the highly educated,

and for those whose occupations involve higher levels of cognitive

complexity. We conclude that the daddy bonus increases the earnings

of men already privileged in the labor market.

We dened rst-time fatherhood as a man who became a father by

birth or adoption and who co-resides with the child (thus, single

fathers who co-reside with their child(ren) are included). We argue

that the earnings of unmarried fathers who do not co-reside with their

newborn are unlikely to be impacted by either the caring responsibilities

or the social status changes associated with participatory fatherhood.

We focus on the transition to fatherhood, rather than number of

children, because this transition will trigger any dierential treatment

of men in the workplace based on fatherhood status. On the family

front, fatherhood status, rather than number of children, also predicts

increased men’s time in childcare activities. Time-use evidence shows

that while fathers spend more time than childless men in childcare

(just under one hour daily), fathers’ childcare time declines as the

number of children in the home increases.

9

e opposite is true

for women (childcare time increases with more children born),

presumably because with larger numbers of children, fathers and

mothers experience greater gender divisions of paid and unpaid work.

The

combination

of uneven

fatherhood

bonuses and

motherhood

penalties

implies

increasing

inequality

among

heterosexual,

two-parent

households

with children.

10

THIRD WAY NEXT

Why might men’s earnings rise when they become fathers? ere

are two possible explanations. A wage increase at fatherhood could

result from a “treatment” eect or a “selection” eect. e selection

argument states that the same factors that predict higher wages among

men also predict greater likelihoods of becoming a father. is is an

example of positive selection into fatherhood: Men who would have

earned more, on the basis of their characteristics, are also more likely

to be fathers, thus rendering the relationship between fatherhood and

earnings spurious. e selection eect suggests that what appears to

be a positive eect of fatherhood is really due to men who have higher

earnings potential being more likely to become fathers. By using xed-

eects techniques, our statistical models control for stable unmeasured

dierences among men, including innate intelligence, social class

background, and career-orientation. (See appendix for details on xed

eects regression and the modeling strategy.)

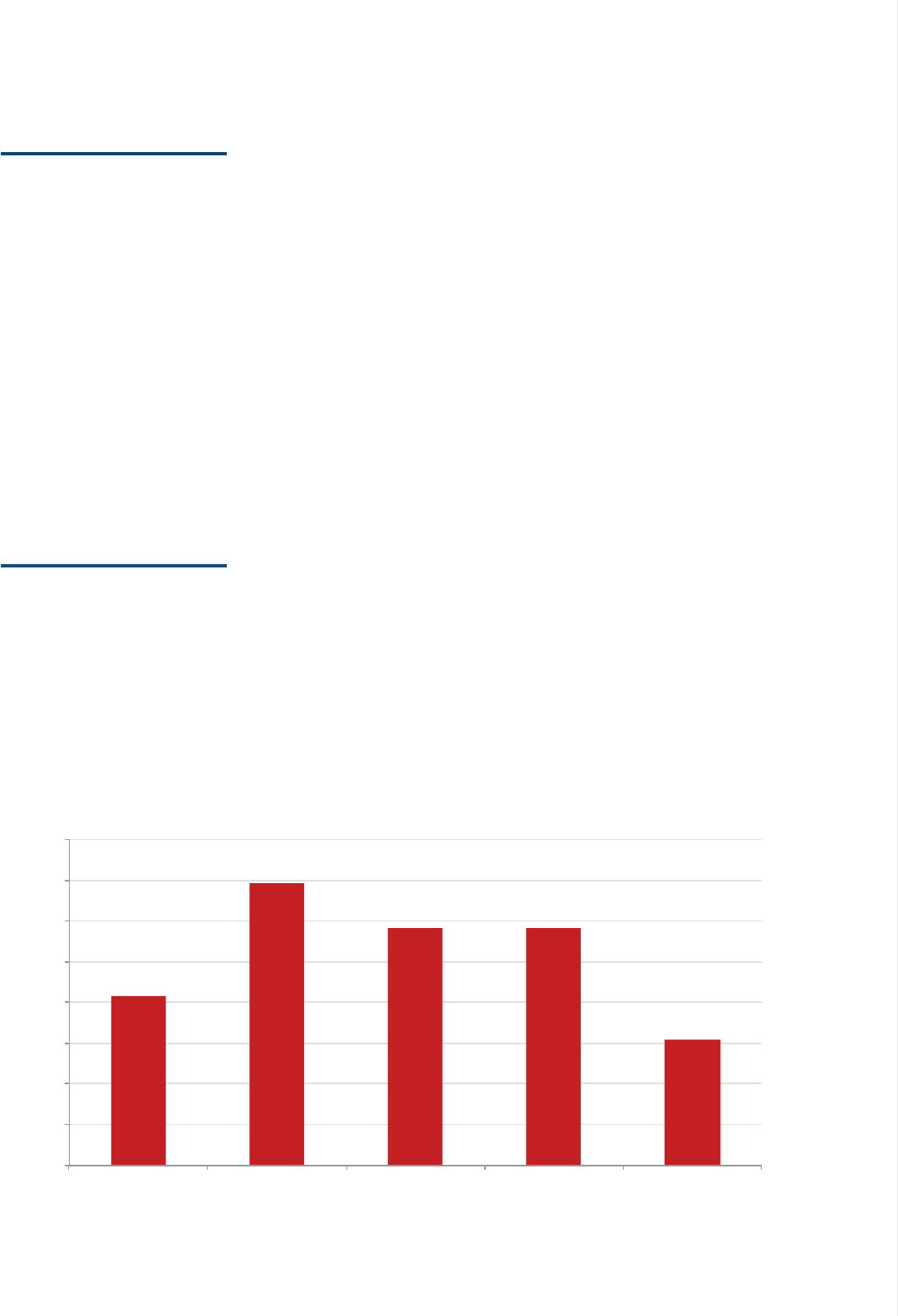

In Figure 3, the rst model using ordinary least squares (OLS),

regression shows an eect of fatherhood on men’s earnings of 8.3%.

is means, holding region and urban area constant, men’s wages

rise, on average, by 8% when they become fathers. e second model

incorporates xed-eects, which remove the impact of stable dierences

among men in shaping this eect (i.e., if smarter or stronger men are

more likely to become fathers and smartness and strength are related

to pay and thus generating the fatherhood bonus, xed-eects models

controls for this). Surprisingly, we nd that the fatherhood bonus is

Figure 3. Effect of Becoming a Father on Ln Annual Earnings: NLSY 1979-2006

11

8.33

13.88

11.63 11.63

6.18

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

OLS model FE model +Human Capital +Work Hours +Marital Status

% Change in Annual Earnings due to Fatherhood

What appears

to be a positive

effect of

fatherhood is

really due to

men who have

higher earnings

potential being

more likely

to become

fathers.

11

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

larger in xed eects models, of almost 14%. is suggests negative

selection into fatherhood, consistent with past research.

10

Negative

selection means that the characteristics that predict lower wages are

associated with greater likelihoods of becoming a father, indicating

that men with less education or job experience, for example, are more

likely to become fathers at younger ages.

In the human capital model, we test whether men with greater human

capital are more likely to become fathers and earn higher wages. If

this is the case, the fatherhood bonus would be spurious, or approach

zero. Including these controls reveals that men receive a wage bonus

of 11.6% when they become fathers. is means that men’s wages

in their post-fatherhood years are, on average, 12% higher than in

their pre-fatherhood years, net of statistical controls. It also means

that there is some positive selectivity into fatherhood, thus the bonus

with human capital controls is slightly smaller than the bonus without

the controls. Finally, because fathers are disproportionately married

relative to childless men, we add a control for marital status. is

shrinks the fatherhood bonus to 6.2%, but it remains signicant.

One version of the treatment argument regarding the fatherhood

bonus suggests that men might change their work-related behaviors

when they become (or anticipate becoming) fathers in ways that

increase their pay. Indeed, previous studies nd that men’s work hours

and eort increase following a child’s birth, particularly when mothers

reduce their work hours.

12

Our fourth model controls for changes in

work eort, however the wage bonus for fatherhood is unchanged

compared to the human capital model that lacks these controls. In

both models the eect of fatherhood nets an 11.6% earnings bonus.

But perhaps it is not men’s work hours that matter, but their wives/

partners’ work hours. If fathers have female partners who do not work,

or work part-time, these partners may take on even greater shares of

family life responsibilities, freeing these fathers to focus on employment,

relative to fathers whose partners are employed full-time and unmarried

men. Yet, when we include measures of female partners’ work hours in

the model, the fatherhood bonus is unchanged. Past research conrms

this robust nding of fatherhood bonuses regardless of wives’ work

hours: Even when wives work continuously after a birth, husbands

earnings still rise.

13

is implies a dierent type of treatment eect.

An alternative treatment argument is that others—employers,

coworkers, hiring agents—treat male workers dierently based on their

fatherhood status. While the survey data we use does not allow us to

Among men

with equivalent

resumes,

fathers are

more likely to

receive call-

backs and

higher wage

offers than are

childless men.

12

THIRD WAY NEXT

test for favorable treatment of fathers in the workplace, evidence from

experimental and audit studies suggest that fathers receive preferential

treatment over childless men from potential employers. Shelly Correll

and her colleagues found that among men with equivalent resumes,

fathers are more likely to receive call-backs and higher wage oers

than are childless men.

14

Fatherhood may serve as a signal to potential

employers for greater maturity, commitment, or stability. In the context

of higher employer expectations for the “family man,” they found

that fathers are given less scrutiny for poor performance and more

opportunities to demonstrate their abilities than are childless men.

If fatherhood confers a more favored status on male workers, how

does it link to other status hierarchies in the workplace? Our analyses

nd that while all men experience a wage bonus for fatherhood,

the size of the bonus varies by racial/ethnic group, educational

attainment, professional status, and skill demands of the occupation.

To demonstrate this, we re-estimated the fth “Marital Status”

model and included statistical interactions between fatherhood and

racial/ethnic group, between fatherhood and professional status, and

between fatherhood and occupational skill demands. Figure 4 shows

the signicant dierences for these comparisons. In regard to racial/

ethnic dierences, white men receive larger fatherhood bonuses than

do black men or Latinos. Among white men, this bonus is larger for

professionals and managers ($3,044; in 2006 dollars) than for non-

professionals and non-managers ($2,020), and it is larger for men

in occupations with high cognitive demands ($6,033) compared to

low cognitive demands ($2,104). College educated white and Latino

men receive signicantly larger fatherhood bonuses than less educated

men of the same race. White college educated men receive an average

fatherhood bonus of $5,258 while Latino college graduates receive

an average fatherhood bonus of $4,170. is is relative to bonuses of

roughly $2,200 among less educated white men, $1,400 among less

educated Latinos and $1,500 among all African-American men.

In summary, our ndings point to signicant wage bonuses for

fatherhood that cannot be explained by dierential selection into

fatherhood on factors that lead to higher wages. Moreover, this bonus

cannot be explained by fathers’ or their partners’ changed work hours

following the birth of a child. Our ndings show that fatherhood

bonuses are ever-larger for more privileged men. is, in combination

with past ndings of employer preferential treatment of fathers, suggests

that fatherhood is a valued characteristic of employers, signaling perhaps

Fatherhood

is a valued

characteristic

of employers,

signaling

perhaps

greater work

commitment,

stability, and

deservingness.

13

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

greater work commitment, stability, and deservingness. Men’s traits that

are valued in organizational settings combine with fatherhood to produce

larger earnings bonuses. White (and sometimes Latino) married college

graduates in professional occupations receive the largest fatherhood

bonuses. Notably, none of these factors serve to alter the fatherhood

bonus among African-Americans, which remains the lowest of all racial/

ethnic groups in every analysis. In summary, men who are either better

positioned or more valued due to their race/ethnicity, human capital,

and professional standing receive a larger earnings bonus for fatherhood.

MOTHERHOOD WAGE PENALTY: THE

COST OF EACH ADDITIONAL CHILD ON A

WOMAN’S WAGE

In contrast to men, the impact of minor children in the home on

women’s earnings is negative. In a set of studies, we have established

two major ndings. First, there is a wage penalty for motherhood

of 4% per child that cannot be explained by human capital, family

structure, family-friendly job characteristics, or dierences among

women that are stable over time. Second, this motherhood penalty is

larger among low-wage workers while the top 10% of female workers

incur no motherhood wage penalty.

Figure 4. Fatherhood Bonus in Dollars, by Professional Status, Occupational Cognitive

Demands Education (OCD), and Race/Ethnicity, Adjusted for Human Capital

15

$(500)

$500

$1,500

$2,500

$3,500

$4,500

$5,500

$6,500

Baseline Non-

Professional

Professional Low OCD Medium OCD High OCD College

Graduate

White Black Latino

In contrast

to men, the

impact of

minor children

in the home

on women’s

earnings is

negative.

14

THIRD WAY NEXT

It is widely documented that American women experience a wage penalty

for motherhood.

16

ere are at least ve explanations for the association

between motherhood and lower wages. First, many women spend time

at home caring for children, and thus interrupt their job experience, or at

least full-time job experience, and this can lead to lower wages. Second,

mothers may trade higher wages for “mother-friendly” jobs that are

easier to combine with parenting. ird, mothers may earn less because

the needs of their children leave them exhausted or distracted at work,

rendering them less productive. Fourth, employers may discriminate

against mothers by assuming lower work commitment or performance.

Finally, like the selection argument for the fatherhood bonus above,

women who are less likely to earn higher wages may be more likely to

become mothers, and the relationship between motherhood and wages

can be explained by these other factors.

In my 2001 publication with Paula England, we investigated these

arguments using NLSY79 data and xed-eects models (again, similar

to those presented in the fatherhood bonus section). e analysis

diers, however, in its measure of children and the inclusion of single

parents. We argue above that the status of becoming a father activates

changed behaviors among men (e.g., increased work hours) and

changed treatment of men by employers and co-workers (e.g., view a

father as a more committed worker than a childless man). However,

because women, on average, perform more of the care work of bearing

and raising children, each additional dependent child (under age 18)

that she has will impact her time allocations to home and work, as well

as her opportunity costs for remaining employed while childcare costs

increase. In addition, in contrast to the analysis above that did not

include non-coresidential single fathers, we include single mothers

who co-reside with their newborns (but not the baby’s father) in this

analysis. is is because while there is a signicant number of single

mothers in the data, there are virtually no co-residential single fathers.

FINDINGS

e gure below mimics (in the opposite direction) the gure for the

fatherhood bonus in presenting tests of these competing explanations.

For the methods and models producing the gures below, please see

the appendix.

In the rst model using OLS regression we nd a wage penalty of

-7.8% per child, such that a mother of two children would be

expected to have a -15.6% penalty. When we control for stable

It is widely

documented

that American

women

experience

a wage

penalty for

motherhood.

15

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

dierences among women using xed-eects in the second model,

we again nd a motherhood wage penalty, but of a slightly smaller

-6.7% per child. is indicates some level of negative selection into

motherhood, meaning women whose stable characteristics predict

lower earnings also somewhat predict greater fertility. We next include

marital status and nd the penalty rises a bit to -7.04% per child. is

is because married women incur larger motherhood penalties than do

single women. When we introduce human capital measures for job

experience, seniority, education, and job turnover, the motherhood

penalty is reduced to -4.6%. Taken together, human capital dierences

between women with more or fewer children explain about one-third

of the motherhood penalty. But two-thirds of an unexplained penalty

remains. e nal model includes a large array of job characteristics

that might make work more compatible with caring for children. ese

include access to part-time work or a seasonal schedule, measures of

work eort required and amount of “down time” on the job, holding

authority over others, jobs that allow children to be on-location such

as child care employment or self-employment, and the extent to which

the occupation is female-dominated. e thirty-ve job characteristics

entered in this model collectively reduce the motherhood penalty to

-3.6% per child and much of this reduction is due to part-time work.

us, while reduced human capital is a signicant explanation for

one-third of the motherhood wage penalty, we nd little evidence that

Figure 5. Effect of Each Additional Child on Women’s Ln Hourly Wage: NLSY

1979-1993

17

-7.78

-6.57

-7.04

-4.59

-3.63

-9

-8

-7

-6

-5

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

OLS Fixed Effects + Marital Status + Human Capital + Family-friendly Job

Characteristics

% Change in Hourly Wage for Each Additional Child

Human capital

differences

between

women with

more or fewer

children explain

about one-

third of the

motherhood

penalty. But

two-thirds of

an unexplained

penalty

remains.

16

THIRD WAY NEXT

family-friendly job characteristics can account for why moms earn less

than childless women.

e import of this research shows that having children reduces women’s

earnings, even among workers with comparable qualications,

experience, work hours, and jobs. Research on the motherhood penalty

has used a variety of regression methods to estimate the average impact

of children on women’s average earnings. But the average eect doesn’t

tell us about dierences among women workers, or whether highly-

paid women incur smaller or larger penalties for children compared to

women with lower earnings.

Given the complex pressures and resources that women at varying

earnings levels encounter both at home and at work, it is reasonable

to expect dierences in the processes leading to motherhood wage

penalties among workers with at varying earnings levels. First, the

composition of workers on factors shaping the motherhood penalty

may systematically dier by earnings level. For example, relative to

low-wage workers, high-earning women are likely to live in households

with greater resources (e.g., a marital partner, higher family income),

possess greater human capital (education), and hold jobs with more

family-friendly characteristics (health benets, greater autonomy and

exibility). e greater assets possessed by higher earners may enable

mothers to more easily replace their child caregiving with high-quality

services, therein providing both a motivation to increase earnings and

the ability to reduce work-family conict. is may result in smaller

motherhood wage penalties relative to lower-wage women. On the

other hand, these same household resources might enable high-wage

mothers to reduce their labor force participation when children are

small, through employment interruptions and reduced working hours.

If so, motherhood penalties might be larger among high-wage workers.

In addition to having dierent amounts of resources among women

located at varying points in women’s earnings distribution, the degree to

which these resources matter may vary by earnings level. For example,

higher earning women are more likely to have maternity leave benets

than low-wage women. Moreover, employers may interpret taking leave

around a birth dierently for high earning versus low wage women.

Employers might see maternity leave as an investment in the retention

of highly-paid skilled women workers, but as a signal of lowered stability

and commitment among low-wage workers, thus low-paid workers

who take time o to give birth may face more employer discrimination

for doing so, relative to highly paid workers. To do this, we estimate

While reduced

human capital is

explanation for

one-third of

the motherhood

wage penalty,

we find little

evidence that

family-friendly

job characteristics

can account

for why moms

earn less than

childless women.

17

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

quantile regression models (see appendix for details) to calculate how

children impact earnings for workers at dierent percentiles of women’s

wage distribution. We specify the following percentiles: 5th, 10th, 25th,

50th (median), 75th, 90th, and 95th. ese quantiles correspond to

hourly wages (in 1996 constant dollars) of $4.35, $5.17, $6.48, $9.06,

$13.45, $20.36, and $34.70, respectively. We can then compare whether

the motherhood wage penalty diers between women with very low,

moderate, and very high wages.

FINDINGS

While the average penalty for all women in the full model is about 4%

per child, the penalty ranges in size from 6% per child among low-

wage workers to no penalty among the earners at the 90th percentile

or above. e gure below shows the impact of children on women

located in dierent places in the distribution of all women workers’

earnings. e horizontal, or X, axis shows the quantile, or position,

in the distribution of women’s earnings. e vertical, or Y, axis shows

the percentage eect of a child on women’s earnings. e dashed line

shows the percentage change in earnings for each additional child,

controlling for marital status, region of residence, and xed eects.

us, at the 0.05 location, or 5th percentile of women earners, the per-

child wage penalty is 6.8%. e motherhood wage penalty declines

among higher-earning women, and among women in the top tenth

percentile, or at the 0.90 and 0.95 quantiles, we nd no or positive

eects of children on earnings.

e solid line in the gure above shows the impact of each additional

child on women’s earnings after we control for human capital

measures. e human capital model includes variables for marital

status, husbands’ annual earnings, husbands’ work hours, women

respondents’ work hours, annual weeks worked, education, years of

experience, years of seniority, enrollment status, and whether the

woman respondent changed employers in the past year. Once again

we see that lost work experience and seniority captured in the human

capital model partially explains the motherhood penalty: at mothers

work less and may accept lower earnings for more family-friendly

jobs partially explains the penalty among low-wage workers, and that

mothers have less experience, due to interruptions for childbearing,

explains some of the penalty among the highly paid. But a signicant

motherhood penalty persists even in estimates that account for these

dierences: the size of the median wage penalty after all factors are

The average

penalty for

all women in

the full model

is about 4%

per child, the

penalty ranges

in size from 6%

per child among

low-wage

workers to no

penalty among

the earners.

A significant

motherhood

penalty

persists even

in estimates

that account

for these

differences.

18

THIRD WAY NEXT

controlled is roughly 3% per child, which means the typical full-time

female worker earned $1,200 less per child (in 2010 dollars).

Results show the largest motherhood wage penalties at the bottom of

the unconditional earnings distribution, with percentage eects of -5.9

and -0.057 at the 5.5 and .25 quantiles, respectively. e .10 quantile

has a slight blip upward, though still with a signicant motherhood

penalty. Mothers at the top of the unconditional wage distribution are

not penalized. We observe that women at the .90 and .95 quantiles

indeed receive a wage bonus for children of 1.7% and 5.4% per child,

respectively. is striking nding of a motherhood bonus among the

top earners is observed by other scholars: Anderson and colleagues nd

a motherhood bonus of 10% for one child and 7% for two or more

children among college-educated women, and Amuedo-Dorantes

and Kimmel nd a 4% premium for motherhood among college-

educated women, and a 13% premium for delayed motherhood

among the college educated.

19

Among very high earners, mothers may

earn enough to make a diverse array of domestic services –nannies,

chefs, restaurants, cleaning services, etc.—aordable and allowing

them to specialize more at work. e cost of such arrangements might

motivate highly-paid mothers to earn ever higher wages, possibly

Figure 6. Effect of Each Additional Child on Ln Hourly Wage by Wage Quantile,

Controlling for Human Capital, Family Structure, and Demographic Variables

with Fixed Effects: NLSY 1979-2004

18

Mothers at

the top of the

unconditional

wage

distribution are

not penalized.

19

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

producing the child bonus we observe. It is also possible that high-

performing women receive favorable treatment from employers for

having children, similar to the way men receive favorable treatment

and a wage bonus for fatherhood.

20

We nd no evidence that these

rare motherhood premiums are attributable to having less-employed

spouses; if anything, it appears that high earning women with fully

employed husbands are the most likely to receive a motherhood

premium. Beyond these instances of motherhood premiums for very

high-earning married women, our analyses generally show motherhood

penalties for all women, but consistently smaller proportionate

motherhood penalties for the highest-paid workers. Taken together,

these ndings suggest that high-income women and all men are less

likely to experience the negative earnings impacts that children have

on comparatively lower wage female workers.

We considered whether larger penalties among the lowest-paid might

be due to their attempts to keep wages low enough to receive social

welfare. However, in supplemental analyses we found that receipt of

AFDC and TANF payments is not linked with variation in the size of

the motherhood penalty. It is well-documented that women located

on the lower end of the earnings distribution experience diculty

combining work and family obligations. ese jobs typically entail

the fewest benets (health, life, and sick time), the closest supervision,

and the least autonomy in setting the pace and intensity of work.

Indeed, when we analyze penalties by age of the child, we see that

the penalty per preschoolers is almost ve times as great at the lowest

quantile of earnings, compared to higher quantiles. Yet the same

pattern does not appear for older child penalties (children aged 6

and to 18 years). is again speaks to the diculty of combining

intensive family responsibilities with work responsibilities in low-paid

jobs: When physical care demands for children are greatest during the

preschool years, low-earning mothers incur the largest penalties. Also

supporting this argument is that we see that work eort accounts for

signicantly more of the motherhood penalty at the lowest quantile,

indicating women with low-wage jobs are more likely to reduce work

hours or experience job turnover to accommodate motherhood.

Employer changes induced by work-family conict may account for

some of the unexplained penalty at the lowest quintiles. One solution

to work-family conict for low-income mothers without access to

family leave or subsidized daycare may be simply quit their jobs with

the intent of starting over when family crises abate. e job-quit

Taken together,

these findings

suggest that

high-income

women and

all men are

less likely to

experience

the negative

earnings impacts

that children have

on comparatively

lower wage

female workers.

The penalty per

preschoolers is

almost ve times

as great at the

lowest quantile

of earnings,

compared to

higher quantiles.

20

THIRD WAY NEXT

solution to resolve child care crises is likely more common among

low-wage workers due to the high costs of formal childcare and their

greater reliance on unpaid relatives and friends as caregivers. ese

friends and relatives of low-wage workers are likely to be facing their

own nancial and personal challenges, resulting in inconsistent care

availability. Moreover, childcare tends to be least available in poor

communities, where low-wage women more likely live. Whatever the

source, it is clear that, according to our results, the women who least

can aord it pay the largest proportionate penalty for motherhood.

Might employer discrimination lie behind the motherhood penalty

that is unexplained by measurable characteristics of workers and jobs?

It is dicult to obtain data on discrimination. However, evidence

from experimental and audit studies support arguments of employer

discrimination against mothers in callbacks for job applications, hiring

decisions, wage oers, and promotions. As previously mentioned,

Stanford sociologist Shelley Correll’s experimental research shows that,

after reviewing resumes that diered only in noting parental status

(simply by stating membership in a Parent-Teacher Association),

applicant evaluators in an experiment systematically rated childless

women and fathers signicantly higher than mothers on competency,

work commitment, promote-ability, and recommendations for hire.

Most telling, applicant raters gave mothers the lowest wage oers,

averaging $11,000 lower than wage oers for childless women and

$13,000 lower than wage oers for fathers. In their audit study,

Correll and colleagues found evidence that mothers may suer worse

job-site evaluations, being scored as less committed to their jobs, less

dependable, and less authoritative than non-mothers.

21

While Correll’s work focused on highly-paid professional employment,

it could also be that among low-wage workers employers view family

responsibilities among female employees as a source of instability and

fail to hire or promote them to a greater extent than employers of

higher-paid workers. What is important to note about Correll’s research

is that her experimental and audit studies showed disadvantage for

mothers and advantage for fathers relative to childless persons even in

the absence of evidence of dierential performance or commitment by

the job applicants. Why would potential employers review equivalent

resumes in such disparate ways? Stereotypical gender expectations for

fathers and mothers in relation to caring for others and focusing on

paid work oer a potential explanation. Ideas of what make a “good

mother,” a “good father,” and an “ideal worker” matter. If mothers

The women

who least can

afford it pay

the largest

proportionate

penalty for

motherhood.

Evaluators in

an experiment

systematically

rated childless

women

and fathers

significantly

higher than

mothers on

competency, work

commitment,

promote-ability, &

recommendations

for hire.

21

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

are supposed to focus on caring for children over career ambitions,

they will be suspect on the job and even criticized if viewed as overly

focusing on work. Correll et al found that mothers face discrimination

even when they demonstrate competence and commitment. Evaluators

viewed highly successful (on the job) mothers as less likeable, less

warm, and more interpersonally hostile than non-mothers. Even

when mothers break the stereotype of prioritizing family over work,

they face discrimination in the workplace. e opposite is true for

fathers. Correll’s research nds that fathers are given more breaks

or opportunities despite poor performance compared with non-

fathers, as discussed above. Moreover, my research shows that these

discriminatory processes may be linked to wage inequalities.

CONCLUSION

In this report I have identied the persistent gender gap in pay that,

despite shrinking during the 1980s and 1990s, reached a woman’s 81

cents per man’s dollar in 2003 and has stalled there since. In considering

the factors that could contribute to this stubborn gap, I’ve targeted

the dierential impact of parenthood on women’s and men’s earnings.

Current data on full-time workers shows that the gender pay gap is

quite small among childless and unmarried workers (among whom

women earn 96 cents to a man’s dollar). e gender pay gap is largest

among married parents with a minor child in the home. Among full-

time workers married mothers earn only 76 cents to a married father’s

dollar. In reviewing the research on the motherhood wage penalty

and the fatherhood bonus, I demonstrate that some of the commonly

held explanations for these dierential eects hold some water. It is

true that women decrease work eort by reducing hours or taking

time away from work following the birth of a child, and that this lost

experience accounts for roughly one-third of the motherhood penalty.

Similarly, fathers do increase work eort following the birth of their

rst child and this accounts for at most 16% of the fatherhood bonus.

Importantly for both women and men, accounting for changes in

work behaviors, work eort, and human capital losses/gains associated

with parenthood still leaves the vast majority of motherhood penalties

and fatherhood bonuses unexplained. e argument that women trade

earnings for family-friendly jobs when they have children, and that this

accounts for their wage losses is not well supported by the statistical

analyses. While there may be some unmeasured changes in the relative

productivity of parents compared with childless workers, experimental

It is likely that

the highly

educated men

are paired with

high earning

women. This

indicates that

parenthood

further benefits,

or at least

doesn’t harm,

the earnings of

high-income

families.

22

THIRD WAY NEXT

and audit studies suggest that employers treat parents dierently than

childless workers, to men’s advantage and to women’s disadvantage.

e fact that having children exacerbates gender inequality is troubling

enough, but the analyses indicating that parenthood penalizes lower-

wage working women more and does not benet lower-wage working

men at all has profound implications for growing household or family

inequality. Sociological research demonstrates that people marry

similarly educated people and that education strongly predicts earnings.

us, it is likely that the highly educated men (who receive the largest

daddy bonus) are paired with high earning women (who receive no

motherhood penalty). is indicates that parenthood further benets,

or at least doesn’t harm, the earnings of high-income families. On the

other hand, the large penalties for motherhood experienced by low-

wage female workers and the absence of a fatherhood bonus for less

educated men suggests that parenthood is likely creating signicant

earnings losses for families least positioned to absorb them.

Simply framing parenthood as a “choice” and one for which parents

alone must accept the consequences is an inadequate dismissal of the

eects of gendered parenthood on earnings. Increasingly American

women are “opting out” of parenthood, but not of work. Twenty-four

percent of American women aged 40 to 44 in the 2006-2010 period

were childless, and this number is still higher if one looks at college

graduates.

22

While American fertility remains high relative to other

developed nations, raising the next generation of productive worker-

citizens is key to any country or economy’s survival. Increasingly

this work is being done by families with fewer resources. us, this

research underscores the importance of supporting low-wage families

with children. While there are few transfers to low-income families in

the United States, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) currently

reduces the tax burden of qualifying families by roughly $3,000

for one child to just under $5,000 for two or more children. e

qualifying limits for these modest credits are quite low: Only families

falling within 145% of the poverty line can fully claim this credit (my

calculations from 2008 Census Bureau data). Expanding the EITC to

more families and increasing the tax credit would both reduce child

poverty and reduce the inequality among families generated by sizeable

motherhood penalties and absence of fatherhood bonuses among less

skilled and low-income workers.

e motherhood wage penalty and fatherhood bonus are not unique

to American workers, but are found among a number of westernized

Simply framing

parenthood as

a “choice”...is

an inadequate

dismissal of

the effects

of gendered

parenthood on

earnings.

It is likely that

the highly

educated men

are paired with

high earning

women. This

indicates that

parenthood

further benefits,

or at least

doesn’t harm,

the earnings of

high-income

families.

23

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

countries.

23

Notably, these parenthood eects vary across countries

ranging from very large eects in gender conservative countries such

as Austria and Germany, to very small eects in social democratic

countries, such as Sweden. In considering the role of nationalized

work-family policies and the motherhood penalty, our research

indicates that publicly funded childcare, particularly for children

aged 0 to 2 years, is associated with smaller penalties, while extended

parental leaves (up to 3 years in Germany), are associated with larger

wage penalties for mothers.

24

Clearly, public policy related to work-

family issues can impact earnings disparities for parenthood. What

these policies may entail in the American context is an important

debate American policymakers must address.

APPENDIX: METHODS AND MODELS

Fatherhood Wage Bonus

To determine what factors can account for the impact of fatherhood on

men’s wages, we take a nested modeling approach. With this approach

we estimate a baseline model that shows the total eect of fatherhood

on earnings (with minimal controls) and then add sets of theoretically

relevant factors in successive models to investigate how the eect

of fatherhood on earnings changes with additional controls. In this

analysis we estimate a baseline model using Ordinary Least Squares

regression (OLS) and then higher-order models that use a technique

called xed eects regression, which examines change within a man’s

own wage trajectory over time (1979-2006), and estimates how much

of that change is due to the birth of a rst child, net of other factors.

Fixed eects models control for time invariant selection, while OLS

models do not. e importance of reducing selection bias is explained

in the next section.

Nested models are sequential and each higher-order model includes

the variables of the lower-order model, while adding additional control

variables. We rst t ve nested models to examine the mechanisms

thought to explain the fatherhood premium. e baseline model uses

OLS regression and includes controls for time (year of interview),

fatherhood status, age, and demographic controls (urban/rural status).

e second model re-estimates the baseline model with xed-eects

regression. e third model adds human capital measures (education,

current school enrollment, seniority (years of experience with current

employer), and years of total work experience. e fourth model

adds measures for work eort (respondent’s usual weekly hours, usual

Raising the

next generation

of productive

worker-citizens

is key to any

country or

economy’s

survival.

Increasingly this

work is being

done by families

with fewer

resources.

24

THIRD WAY NEXT

hours squared, annual weeks worked, and total number of jobs ever held). Model 5 controls

for marital status. After examining the additive eects of these explanatory mechanisms,

we investigate statistical interactions between fatherhood and a number of other factors,

including household division of labor, educational attainment, professional/managerial

status, and occupational cognitive demands. ese interactions show under what conditions

the fatherhood bonus is amplied or diminished.

Motherhood Wage Penalty

Models presented in gure 5: Parallel to the fatherhood bonus analysis, we run a series of

nested models to examine whether competing explanations can account for the motherhood

penalty. e OLS model utilizes robust standard errors and includes respondents’ age and

year of interview, each in linear, squared, and cubed form. e baseline xed eects model

includes person and year xed eects. e marital status model adds marital status to the FE

model. e human capital model additionally includes education, years of seniority, years

of experience, current school enrollment, and number of employment breaks. e family-

friendly job characteristics model adds part-time status; percent female of respondents’

occupation and industry; occupational characteristics including reported work-eort

required, percent of downtime (waiting or goong o), hazardous job conditions, strength

requirements, cognitive demands, specic vocational training requirements, and authority;

and dichotomous measures for unionization, public sector job, self-employed, child-care

occupation, and industrial sector.

Models presented in gure 6: In recent publications (Budig and Hodges 2010; Budig and

Hodges forthcoming) using NLSY79 data covering the 1979-2004 period, Melissa Hodges

and I show how the motherhood wage penalty varies across women with dierent levels of

earnings. To do this, we again estimate xed eects models at a baseline (with predictors

for number of children, age of respondent, region of country, and population density) and

a full model (with additional controls for current marital status, spouse’s annual earnings,

spouse’s work hours, usual weekly hours, annual weeks worked, highest grade completed,

years of experience, years of seniority, enrollment status, and a dummy variable for changing

employers). To understand how the impact of children is dierent among women with

dierent levels of earnings, we use a method called unconditional quantile regression. While

regression models typically estimate an “average” eect of children on hourly wage, quantile

regression allows for the estimation of eects of children for women at specic percentiles

in the distribution of women’s hourly wages.

25

THE FATHERHOOD BONUS & THE MOTHERHOOD PENALTY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michelle J. Budig, PhD, is a Professor of Sociology at the University of

Massachusetts. Her research interests include labor market inequalities, wage

penalties for paid and unpaid caregiving, work-family policy, and nonstandard

employment. She is currently working on an NSF-funded project on the

predictors of women?s entrepreneurship in westernized countries. Her

research has appeared in the American Sociological Review, Social Forces,

Social Problems, Gender & Society, and numerous other professional journals.

She is a past recipient of the Reuben Hill Award from the National Council on Family Relations,

the World Bank/ Luxembourg Income Study Gender Research Award and a two-time recipient of

the Rosabeth Moss Kanter Award for Research Excellence in Families and Work.

ENDNOTES

1 ABC World News. 2010. “Reverse Gender Gap: Study Says Young, Childless Women Earn More

than Men.” By Sharyn Alfonsi. September 1, 2010. http://abcnews.go.com/WN/reverse-gender-gap-study-

young-childless-women-earn/story?id=11538401

2 Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2013. “Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2012.” U.S. Bureau of Labor

Statistics Report #1045. October 2013.

3 Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013.

4 Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013.

5 Martinez, Gladys, Kimberly Daniels, and Anjani Chandra. 2012. “Fertility of Men and Women

Aged 15-44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006-2010.”: National Health

Statistics Reports: No. 51. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

6 Bianchi, Suzanne, John Robinson, and Melissa Milkie. 2006. The Changing Rhythms of American

Family Life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

7 Polachek, Solomon W. 2006. “How the Life-Cycle Human-Capital Model Explains Why the

Gender Wage Gap Narrowed.” Pp. 102-124 in The Declining Signicance of Gender? Edited by Francine

D. Blau, Mary C. Brinton, and David B. Grusky. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; See also Harkness,

Sara and Jane Waldfogel. 2003. “The Family Gap in Pay: Evidence from Seven Industrialized Countries.”

Research in Labor Economics 1(22):369-413; See also Waldfogel, Jane. 1998a. “Understanding the

‘Family Gap’ in Pay for Women with Children.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 12(1):137-56; See

also Waldfogel, Jane. 1998b. “The Family Gap for Young Women in the United States and Britain: Can

Maternity Leave Make a Difference?” Journal of Labor Economics 16(3): 505-45.

8 Hodges, Melissa and Michelle J. Budig. 2010. “Who Gets the Daddy Bonus? Markers of Hegemonic

Masculinity and the Impact of First-time Fatherhood on Men’s Earnings.” Gender & Society, 24(6):717-745.

9 Sayer, Liana, Suzanne Bianchi, and John Robinson. 2004. “Are Parents Investing Less in Children?

Trends in Mothers’ and Fathers’ Time with Children.” American Journal of Sociology 110(1):1-43.

10 Lundberg, Shelley, and Elaina Rose. 2000. “Parenthood and the Earnings of Married Men and

Women.” Labour Economics 7:689-710.

11 Note: The OLS model uses robust standard errors to adjust for non-independence of the

observations and includes measures of fatherhood status, N-1 dummies for year of interview, respondent’s

age, and demographic indicators for urban, suburban and rural areas, The FE model uses person and

year xed effects, and the variables included are the same as the OLS model. The Human Capital Model

builds on the FE model by adding measures for educational attainment, current school enrollment, years

of job seniority, years of experience, and number of different jobs ever worked by the respondent. The

Work Hours model adds controls to the Human Capital model for usual weekly work hours and annual

26

THIRD WAY NEXT

weeks worked. Finally, the Marital Status model adds a control to the Work Hours model for whether the

respondent is married to the child’s mother.

12 Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie 2006; See also Kaufman, G. and P. Uhlenberg. 2000. “The Inuence

of Parenthood on the Work Effort of Married Men and Women.” Social Forces 78:931-49; See also Knoester,

C. and D. Eggebeen. 2006. “The Effects of the Transition to Parenthood and Subsequent Children on Men’s

Well-being and Social Participation.” Journal of Family Issues 27:1532-60; See also Lundberg and Rose, 2002.

13 Lundberg and Rose 2002.

14 Correll, Shelly, Stephen Benard, and In Paik. 2007. “Getting a Job: Is there a Motherhood

Penalty?” American Journal of Sociology 112(5):1297-1339.

15 Note: All models presented in this graph are xed-effects models that include full controls from

the “Marital Status” model presented in above: fatherhood status, respondent’s age, urban/ suburban/

rural area, education, current school enrollment, years of job seniority, years of experience, number of

different jobs ever worked, usual weekly work hours, annual weeks worked, and marital status.

16 Anderson, D., M. Binder, and K. Krause. 2003. “The Motherhood Wage Penalty Revisited:

Experience, Heterogeneity, Work Effort, and Work-Schedule Flexibility.” Industrial and Labor Relations

Review 56:273-94; See also Avellar, S. and P. Smock. 2003. “Has the Price of Motherhood Declined

over Time? A Cross-Cohort Comparison of the Motherhood Wage Penalty.” Journal of Marriage and

the Family 65:597-607; See also Budig, Michelle J. and Paula England. 2001. “The Wage Penalty for

Motherhood.” American Sociological Review 66:204-225; See also Budig, Michelle J. and Melissa Hodges.

2010. “Differences in Disadvantage: How the Wage Penalty for Motherhood Varies Across Women’s

Earnings Distribution.” The American Sociological Review 75(5):705-28; See also Glauber, Rebecca.

2007a. “Marriage and the Motherhood Wage Penalty among African Americans, Hispanics, and Whites.”

Journal of Marriage and the Family 69:951-61; See also Waldfogel, Jane. 1997. “The Effect of Children on

Women’s Wages.” American Sociological Review 62:209-17.

17 Notes: The OLS model utilize robust standard errors and include respondents’ age and year of

interview, each in linear, squared, and cubed form. The Fixed Effects model includes person and year xed

effects. The Marital Status model adds marital status to the FE model. The Human Capital model adds

education, years of seniority, years of experience, current school enrollment, and number of employment

breaks to the Marital Status model. The Family-Friendly Job Characteristics model includes part-time status;

percent female of respondents’ occupation and industry; occupational characteristics including reported

work-effort required, percent of downtime (waiting or goong off), hazardous job conditions, strength

requirements, cognitive demands, specic vocational training requirements, and authority; and dichotomous

measures for unionization, public sector job, self-employed, child-care occupation, and industrial sector.

18 Notes: The Baseline Model includes number of children, age of respondent, region of country,

and population density. The Human Capital Model adds controls for current marital status, spouse’s annual

earnings, spouse’s work hours, usual weekly hours, annual weeks worked, highest grade completed, years

of experience, years of seniority, enrollment status, and a dummy variable for changing employers.

19 Anderson, D., M. Binder, and K. Krause, 2003; See also Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina and Jean

Kimmel. 2005. “The Motherhood Wage Gap for Women in the United States: The Importance of College

and Fertility Delay.” Review of Economics of the Household 3:17-48.

20 Correll, Shelly, Stephen Benard, and In Paik, 2007; See also Hodges, Melissa and Michelle

J. Budig, 2010; See also Glauber, Rebecca. 2007b. “Race and Gender in Families and at Work: The

Fatherhood Wage Premium.” Gender and Society 22: 8-30.

21 Correll, Shelly, Stephen Benard, and In Paik, 2007.

22 Martinez, Gladys, Kimberly Daniels, and Anjani Chandra, 2012.

23 Budig, Michelle J., Joya Misra, and Irene Boeckmann, 2012; See also Budig, Michelle J. and Melissa

Hodges. Forthcoming. “Statistical Models and Empirical Evidence for Differences in the Motherhood Wage

Penalty Across the Earnings Distribution: A Reply to Killewald and Bearak.” American Sociological Review;

See also Boeckmann, Irene and Michelle J. Budig. 2013. “Fatherhood, Intra-Household Employment

Dynamics, and Men’s earnings in a Cross-National Perspective.” LIS Working Paper No. 529.

24 Budig, Michelle J., Joya Misra, and Irene Boeckmann. 2012.