28 August 2015

Corporate Funding Structures and Incentives

Final report

Introduction

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, a concerted effort has been made to reduce

leverage in the financial sector. For instance, the aggregate leverage of large internationally

active banks declined from 29 times Tier 1 capital in 2011 H1 to 22 times in 2014 H1.

1

Such

reductions are helping to reduce the vulnerability of the financial system to shocks.

However, broader measures of debt and leverage, which cover both financial and nonfinancial

sectors, have continued to grow in many countries.

2

Leverage in nonfinancial sectors in the

economy can also represent a vulnerability, because it can act to amplify changes in

fundamentals and make households, nonfinancial businesses and governments more sensitive

to shocks. Some studies find that excessive debt can dampen economic growth. It has been

shown to lead to financial crises and to hamper economic recovery from recessions.

3

In the post-crisis period, there has been a noteworthy increase in nonfinancial corporate debt,

particularly in some emerging economies. This has taken the form both of bond issuance and

bank borrowing. In aggregate, this has led to higher levels of corporate leverage as measured

by the ratio of nonfinancial corporate debt to GDP. Questions have been raised about the

incentives that have led to this increase and whether the trend represents a risk to financial

stability.

1

See Basel Committee for Banking Supervision, Basel III Monitoring Report 2015, Table A.16.

2

According to one estimate, the global stock of debt (summing household, corporate, government and financial) rose from

$142 trillion (269% of GDP) at end-2007 to $199 trillion (286% of GDP) in the second quarter of 2014. McKinsey

Global Institute (2015), “Debt and (Not Much) De-leveraging,”

http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/economic_studies/debt_and_not_much_deleveraging. The Report examines the

evolution of debt in 47 countries around the world, including both developed and emerging economies. Similarly,

Buttiglione et al estimate that the global ratio of gross nonfinancial debt to GDP has risen every year since 2000 from

160% to 215%. (For details, see Buttiglione, L., Lane, P.R., Reichlin, L., Reinhart, V., (2014), “Deleveraging? What

Deleveraging?” Geneva Reports on the World Economy 16, International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies and

CEPR.

3 For recent studies on the inverse relationship between debt and growth, see Kumar, M.S. and J. Woo (2010), “Public debt

and growth”, IMF Working Paper, No. 10/174, Reinhart, C. M. & Rogoff, K. S., (2010) “Growth in a Time of Debt.

American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 100(2), 573-78. Cecchetti, S., Mohanty, M., Zampolli F., (2011)

“The Real Effects of Debt” BIS Working Papers, No:352. Reinhart, C., Reinhart, V., Rogoff K., (2012) “Public Debt

Overhangs: Advanced Economy Episodes since 1800”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol:26 (3), 69-86.

2

This report responds to the request of G20 Finance Ministers and Governors in their February

2015 communique for “the FSB, coordinating the inputs of the IMF, OECD, BIS, IOSCO and

WBG to prepare a report by our meeting in September preceded by an interim report to the

June Deputies meeting to examine the factors that shape the liability structure of corporates

focusing on its implications for financial stability.”

The report has been prepared by the FSB Secretariat, based on the contributions by the staff of

the six international organisations. It describes:

• the growth in nonfinancial corporate debt since the crisis, including differences across

countries and regions (section 1);

• insights into the incentives, including structural and regulatory factors, influencing

these trends (section 2);

• possible related financial stability concerns (section 3);

• the potential role of macroprudential policies (section 4);

• and possible next steps (section 5).

It focuses on developments and issues for publicly-traded nonfinancial companies. Data on

debt at privately-owned small and medium-sized companies are not widely available; they

may face many of the same incentives and issues as larger companies, but small companies

may also be disincentivised from raising new equity finance by a stronger desire to avoid

dilution of ownership (e.g. where they are family-owned or otherwise closely-controlled).

The way that corporate funding is structured and financed is of interest to authorities because

it will affect the resilience and decision-making of individual corporates and at the aggregate

level could possibly affect the stability of the wider financial system. Corporate funding

markets and corporate liability structures may be relevant for financial stability in a number of

ways.

Well-functioning debt and equity markets allow businesses to fund investment flexibly and at

a relatively low cost to existing shareholders, thereby contributing to investment and growth.

National authorities and international organisations have therefore worked extensively to

encourage the development of such markets.

However, high debt levels relative to equity in corporate balance sheets create leverage which

can accentuate losses to owners, and create elevated debt service requirements. This in turn

can lead to exacerbated cash flow stress, deteriorating creditworthiness, debt-rollover risks

and higher corporate default rates. Moreover, in particular if credit risk is under-priced, spikes

in default rates may permeate through the financial system as investors and creditors,

including the banking system, incur losses. To the extent that there are high and pro-cyclical

levels of corporate leverage that affect a significant number of companies, this may add to

pro-cyclicality of the financial system, and hence reduce financial stability.

The report contains a summary analysis of issues that could have a bearing on financial

stability. It also proposes that there could be further work in 2016, including on: i) further

analysis of data on nonfinancial corporate leverage to examine the extent to which particular

economic factors drive the liability structure choices of different types of corporates and

whether any financial stability concerns arise from these, ii) existing country experiences with

the use of macroprudential tools used to address risks arising from corporate debt financing,

iii) country-specific case studies on addressing the debt-equity tax bias.

3

1. Trends in Corporate Funding Structures

Nonfinancial corporate debt levels have increased relative to GDP over the last 15 years, in

both advanced economies and emerging markets. This increase has been much faster in

emerging markets as their markets have deepened. Nonfinancial corporate debt-to-GDP for a

selected group of advanced economies in 1999 was 77% and for a group of large emerging

market and developing economies (EMDEs) was 38%, but the subsequent rapid growth of

debt in these EMDEs meant that by 2014 the average levels for these EMDEs surpassed the

advanced economies - 87% and 90% (see annexed Tables 1 and 2). This includes a rapid

acceleration of debt growth in EMDEs since pre-financial crisis levels in 2007, as

nonfinancial corporate debt-to-GDP has increased by 31 percentage points for EMDEs, but

only by 2 percentage points for advanced economies during that time.

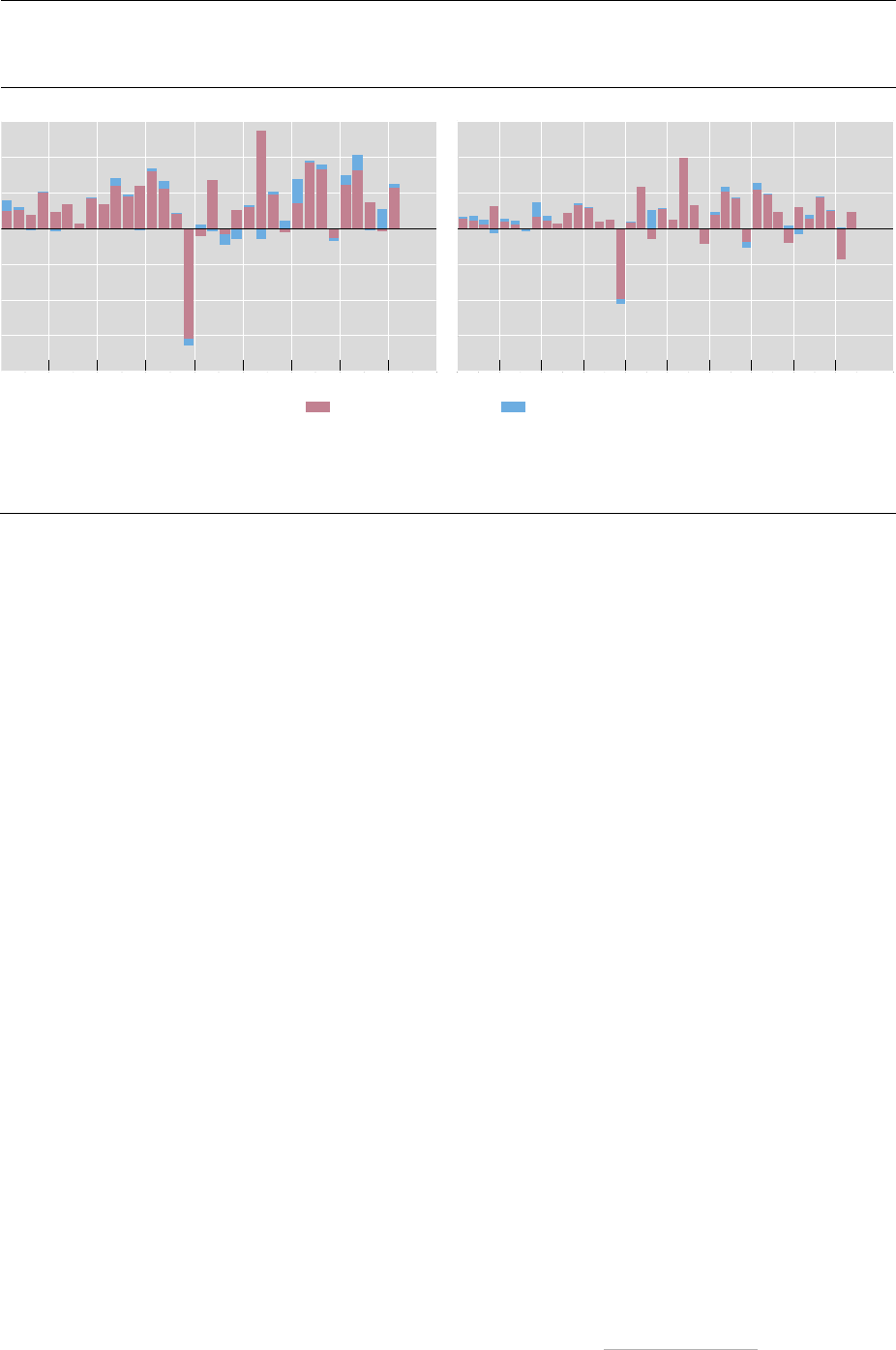

Within the overall figures, there are major differences between countries, both in levels and in

growth rates of nonfinancial corporate debt (see Figure 1). For instance, amongst major

advanced economies, the level of such debt varies from a rapidly-growing 166% of GDP for

Sweden to a flat 55% for Germany, and in some countries corporate debt decreased slightly.

In emerging markets, China’s nonfinancial corporate debt has risen to over 150% of GDP,

above the levels of most advanced economies, while Mexico’s is only 21%. For EMDEs,

growth rates of corporate debt vary considerably across countries. The graphs below illustrate

these developments.

4

Figure 1

- Total non-financial corporate debt (as a percentage of GDP)

Advanced economies

1

Emerging market economies

2

1

Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Hong Kong SAR, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the

United

Kingdom

and the United States.

2

Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia,

Malaysia, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Thailand and

Turkey.

Sources:

IMF, World Economic Outlook; OECD; national sources.

5

Figure 2- Composition of non-financial corporate outstanding debt

(

In trillions of US dollars)

Advanced economies

1

Loans and debt securities

Debt securities

Emerging markets

4

Loans and debt securities

Debt securities, by market

5

1

Countries included are: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Hong Kong SAR, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Si

ngapore, Spain,

Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

2

Total loans to non-financial corporations.

3

Aggregate

outstanding,

by residence of issuer.

4

Countries included are: Ar

gentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Russia, Saudi

Arabia, South Africa, Thailand and Turkey.

5

By residence of issuer.

6

Sum of domestic and international debt securities (see the right

-

hand panel).

Source:

national data, BIS domestic and international debt securities statistics.

Some of this growth in debt in EMDEs is benign and even desirable. In EMDEs with low

starting levels of corporate debt, rising debt may reflect a healthy deepening in the financial

system, as more companies gain access to financial services and as their own financial

condition improves. However, in many EMDEs, corporate debt grew faster than earnings in

2014, with debt-to-earnings now higher than its 5-year average, and according to some

measures risks related to corporate debt have increased. Furthermore, the increased amount of

outstanding debt, declining underwriting standards, and declining secondary market liquidity

conditions, taken together, have increased concerns that a sharp sell-off in corporate debt

markets could produce disorderly conditions in financial markets. Any resulting increase in

financing costs would have negative implications for the real economy.

6

Since the crisis, market sources of credit have become increasingly important (see Figure 2).

In a number of advanced economies, corporate bonds and lending by non-bank institutions

have accounted for nearly all new credit for corporates since 2007, while bank lending to

corporates has shrunk.

4

However in contrast to advanced economies, bank lending in EMDEs

has also risen along with bond issuance.

5

Corporate bonds have assumed a greater role in international fixed-income markets. Issuers

have wide flexibility in how they structure and issue debt securities and the market on which

the debt securities are issued and traded (domestic versus international) and the currency

denomination of the securities (local versus “hard currency”) are two important factors for

financial stability.

Globally, nonfinancial corporates have replaced sovereigns and financial issuers as the largest

bond issuers with US$6.9 trn of issuance since 2008.

6

Not only has the amount of issuance

increased, but between 2008 and 2013 the number of nonfinancial corporates issuing bonds

has doubled, suggesting a deepening of capital markets and an important diversification in the

sources of corporate financing for many corporates (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Global Primary Corporate Bond Markets

Source: Celik, S. et al (2015)

Against the backdrop of ample global liquidity and prolonged low global interest rates,

nonfinancial corporate bond issuance in major EMDEs has risen sharply. New corporate bond

issuance in a selection of major EMDEs rose 10% in 2014, with Asia leading other regions

(Figure 4).

4

The countries mentioned in this context are Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Netherlands, South Korea,

United Kingdom and United States .For details, see McKinsey Global Institute (2015),

5

For details, see Annex A.

6

Celik, S., G. Demirtas, and M. Isaksson (2015), ‘Corporate Bonds, Bondholders and Corporate Governance”, OECD

Corporate Governance Working Papers, No. 16,

http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/oecd-corporate-governance-

working-papers_22230939.

7

Figure 4. Nonfinancial Corporate Bond Issuance by Selected Emerging Economies

1. Bond Issuance by Currency (in US$ billion)

2. Bond Issuance by Regions (in US$ billion)

Source: IMF: Annex A. (The countries in the sample: Argentina,

Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, China, Hungary, India, Indonesia,

Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Russia, South Africa,

Thailand, Turkey)

Source: IMF: Annex A. (Same countries)

Focusing more narrowly on the growth of international bond issuance by EMDEs, the World

Bank paper Global Liquidity and External Bond Issuance in Emerging Markets and

Developing Economies (see Annex B) analyses the global factors that have contributed to this

growth. It notes that bond issuance in international markets by EMDEs (comprising both

corporate and sovereign issuance) increased steadily before the global financial crisis, and

accelerated afterwards. Total annual issuance of international bonds by EMDEs rose from

around $64 bn in 2000 to $400 bn in 2014. In line with the trends outlined above, issuance of

international bonds has been driven in recent years by corporate issuance ($300 bn corporate

vs $99 bn sovereign in 2014, compared to $14 bn corporate and $50 bn sovereign in 2000). In

March 2015, higher-income EMDEs had $1.4 trn of outstanding bonds while lower-income

EMDEs had about $280 bn, both representing all-time highs.

There has also been a shift in EU advanced economies away from a bank-based approach to

corporate funding towards a more diversified corporate funding model, especially for larger

companies. For instance, prior to the crisis nonfinancial corporates accounted for only 17% of

total European financial and nonfinancial corporate bond issuance, but this share had grown

to 40% in 2013.

7

Furthermore, non-investment-grade bonds, which were virtually non-

existent in Europe prior to the crisis, now comprise about 12% of the total amount of

European financial and nonfinancial corporate issuance. Nevertheless, the great majority of

the outstanding stock of European corporate debt remains in the form of bank lending rather

than bonds. At end-March 2014, euro-area nonfinancial corporates still had only EUR 1.1 trn

of outstanding debt securities, compared with EUR 8.6 trn of bank loans.

7

Ibid., p. 14

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

Foreign Currency

Local Currency

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

Asia

Latam

EMEA

8

There are a number of factors explaining these trends. To a certain extent country-specific

factors play a role, such as the continuation of the upward trend in issuance that was already

in place in many fast-growing EMDEs prior to the crisis. However the acceleration of

corporate issuance since the crisis is largely explained by global push factors.

8

Yields on the

sovereign debt of many advanced economies have been low, reflecting the widespread impact

of extraordinary monetary policies conducted by a number of central banks. These actions

have lowered risk premiums and compressed global market volatility, leading to increased

supply from issuers of corporate debt because of the significant reduction in issuance costs

and increased demand from investors for higher-yielding products. This shift has been

reinforced in some cases by the deleveraging taking place in certain banking systems that

have encouraged a substitution towards market-based finance.

However, in the current environment slowing economic growth in EMDEs is putting pressure

on some firms’ profitability and debt service capacity. As noted above, corporate profitability

has declined relative to its five-year averages across most EMDE countries, with broad-based

weaknesses across sectors (see Annex A). Corporate debt has grown faster than earnings in

most EMDE countries over the last several years, evidenced by the increase in the ratio of net

debt to earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT), which suggests that the leverage of EMDE

corporates is increasing, negatively affecting their creditworthiness. The decline in debt-

servicing capacity for some corporates has in part driven the IMF’s estimates that the share of

“debt at risk” in total corporate debt rose by 22% in 2014 from levels in 2010. There could be

value in further examination of the extent to which particular economic factors drive the

liability structure choices of different types of corporates and whether any financial stability

concerns arise from these. For instance, capital-intensive industries (energy sector, mining

sector etc.) tend to have more debt-heavy liability structures, whereas service-oriented firms

tend to have more equity-heavy (including privately-owned) structures. Larger firms are more

likely to issue debt on capital markets than smaller firms, and corporate financing in EMDEs

and the euro area tends to be more bank-based compared to other advanced economies.

Shifting market-based debt characteristics

The increase in the supply of corporate debt has in large part been facilitated by the search-

for-yield environment created by the extraordinary policy measures undertaken in the US,

UK, euro area and Japan. The increased investor demand for riskier and higher yielding

investments has in turn altered the composition of corporate debt markets.

For example, global issuance of non-investment-grade bonds increased from $82 bn in 2000

to $556 bn in 2013, as well as a shift towards debt with fixed-interest and callable features.

9

Maturities for higher-yielding debt have increased; for instance the average maturity of

external issuance by EMDEs has increased to almost 8 years recently, up from 7.3 years in

2009 immediately after the crisis - although it remains below the pre-crisis average maturity

of 9 years. The majority of the total $1.7 trn currently outstanding external EMDE bonds will

mature before 2024, peaking in 2019.

8

For details, see Annex B

9

For details, see Celik, S. et al (2015), including p. 19-20: “A callable bond gives the issuer the option to redeem the bond

prior to maturity. The value of all callable bonds as a share of all corporate bonds issued in 2012 and 2013 exceeded 36%

compared to 16% in 2000.”

9

Covenants have also been relaxed. While the increase in covenant-lite bonds

10

in the US has

been well documented, work by the OECD

11

suggests that globally investor protection

covenants in non-investment-grade bonds are half as common as they were 10 years ago.

Overall, in recent years, the shift in the micro-structure of the corporate bond market has

resulted in greater flexibility for issuers, but potentially greater credit risk for investors (while

diminishing yields have reduced investors’ compensation for that risk).

Another important trend has been the increase in foreign currency corporate funding. BIS

research

12

shows that since the global financial crisis, banks and bond investors have

increased the outstanding US dollar credit to non-bank borrowers outside the US from $6 trn

to $9 trn. This has the potential to create currency mismatches, which may increase financial

stability concerns if a sufficient number of corporates are subject to such mismatches and if

there is no natural hedge and financial instruments for hedging are not available,

as discussed

in section 3 below.

13

2. Structural and regulatory factors influencing corporate funding

structures

When considering relative incentives toward equity and debt financing, a useful starting point

is the Modigliani-Miller theorem

14

, which states that, in the absence of taxes, bankruptcy

costs, agency costs, and asymmetric information, and in an efficient market, the value of a

firm is unaffected by how that firm is financed. However, there are tax, accounting, incentive

and conjunctural factors that in practice limit the neutrality between funding choices.

In this spirit, the academic literature commonly postulates that, when companies seek external

financing, they normally tend to prefer debt to equity, since debt financing entails lower costs

and does not change ownership structures.

15

Additional equity financing is much less

frequent, but will be employed in certain circumstances such as when firms are growing

rapidly or debt levels are high. Empirical studies support these predictions, and suggest a

number of additional firm and industry-specific characteristics that are likely to play a role in

corporates’ funding decisions.

16

10

Covenant-lite bonds are bonds with more relaxed restrictions on collateral, payment terms and other contractual

obligations.

11

See Celik, S. et al (2015)

12

McCauley, R, P McGuire and V Sushko (2015): “Global dollar credit: links to US monetary policy and leverage”,

Economic Policy, April, pp 187–229.

13

For details, Annex E.2

14

Modigliani, F. & Miller, M.H. (1958). “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment".

American Economic Review 48 (3): pp. 261–297.

15

“Pecking order theory” set out by Myers, S.C. (1984). “The Capital Structure Puzzle”, The Journal of Finance, 39 (3), pp.

574-592. This theory is referenced in many subsequent papers, for instance, Fama, E.F. & French, K.R. (2002). “Testing

Trade-off and Pecking Order Predictions about dividends and debt”, Review of Financial Studies, 15(1), pp. 1-33. Frank,

M.Z. & Goyal V.K. (2009). “Capital Structure Decisions: Which Factors are Reliably Important?”, Financial

Management, 38(1), pp. 201-222.

16

In general most of the studies categorise the factors into corporation-specific factors and macroeconomic factors or

country specific factors; such as De Jong, A. Kabir, R & Nguyen, T.T. (2008). “Capital Structure Around the World: The

Roles of Firm-and-Country-Specific Determinants”, Journal of Banking and & Finance, 32(9), pp. 1954-1969, Kayo,

10

This section sets out some of the factors that can be relevant to corporate decisions about their

liability structures.

a. Conjunctural and regulatory factors

Section 1 above described the conjunctural factors leading to increased investor demand for

debt instruments as a result of the extraordinary monetary policies following the financial

crisis. In particular, debt accumulation has been encouraged by the availability of low-cost,

abundant and flexible debt, which has provided an unprecedented opportunity to increase

returns to the equity holders. More generally, debt issuance by nonfinancial corporations is

influenced both by supply-side and demand-side considerations, each with their own policy

implications.

On the supply side of debt issuance, especially for some EMDEs, nonfinancial corporations

have seen growing incentives and opportunities to increase leverage, by borrowing in both

foreign and domestic currencies. The depth of corporate debt markets varies across countries.

Nevertheless, as discussed above, they have taken advantage of the low all-in yields available

to fund expansion plans, where they have stronger growth prospects. Moreover, the increased

depth and breadth of the markets, as well as improved fundamentals in a number of EMDEs

triggering multiple sovereign credit rating upgrades, decreased the risk premium for issuing

EMDE corporate debt.

On the demand side, institutional investors are important investors in global equity and bond

markets, with the overall size of the sector’s balance sheet exceeding the size of the economy

in many advanced economies. While investors have different mandates, incentives and

knowledge of the markets in which they are investing, regulatory developments have

remained an important factor in shaping institutional investors’ asset allocation strategies. In

particular, changes in regulations, in the aftermath of the equity downturn in 2000-2002, have

aimed to incentivise pension funds and insurance companies to reduce their risk profiles and

directly consider asset-liability matching in asset allocation decisions including their demand

for corporate debt.

17

Accordingly, in an effort to de-risk, these investors have tended to shift

their asset allocation decisions away from equities to fixed-income securities. Moreover,

different quantitative restrictions have traditionally been applied for pension funds in many

countries, normally stipulating upper limits on investment in specific asset classes, including

equity. A survey conducted by the OECD states that several countries impose limits on the

proportion of equity held in portfolios, such as Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland,

E.K. & Kimura, H. (2011). “Hierarchical Determinants of Capital Structure”, Journal of Banking & Finance, 35 (2), pp.

358-371. Joeveer, K. (2013), “Firm, Country and Macroeconomic Determinants of Capital Structure: Evidence From

Transition Economies”, Journal of Comparative Economics, 41, pp. 294-308

17

See “Institutional Investors, Global Savings and Asset Allocation”, CGFS papers no:27 (2007), Bank for International

Settlements, accessible at: http://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs27.pdf

11

Germany, Greece, Korea, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Turkey.

18

On the other hand,

demand for both equity and debt securities has been stimulated in some EMDEs by well-

developed pension fund industries (notably in Latin America) and insurance industries

(notably in Asia).

Traditionally bank loans constitute the main source of debt financing for the majority of

European firms. However, deleveraging by banks after the global financial crisis has led to a

shrinkage of bank balance sheets and, for the nonfinancial corporate sector, bank borrowing

has been at least partly substituted by an increase in corporate bond issuance.

The diversification of funding sources should lead to more efficient capital allocation and

better risk sharing, with a positive impact on long term growth. Moreover, local bond

issuance does not share the strongly pro-cyclical behaviour of bank lending.

19

b. Role of tax deductibility

In most corporate income tax systems, interest can be deducted in calculating liability to

corporate taxation but returns to equity cannot.

20

Langedijk et al (2015)

21

states that ‘the

corporate debt bias’ – the asymmetric tax treatment of different sources of finance at the

corporate level - originates from historical conventions and does not have any economic

rationale. This asymmetry distorts incentives in two ways:

Debt bias: an incentive for corporates to prefer debt financing over equity financing

beyond that which would otherwise be justified in economic terms.

Debt shifting: cross-country differences in corporate income tax rates that can lead

corporate groups to conduct internal lending from low-tax countries to high-tax

countries, or by locating external borrowings in high-tax countries (although tax

authorities are likely to challenge artificial structures that are intended to evade tax).

The two are related: within multinational groups, the tax gains from debt shifting may

exacerbate the bias in favour of financing externally by debt.

A sizeable empirical literature finds that tax distortions have a significant and considerable

impact on corporate leverage in the nonfinancial sector: one meta-study (calculating a

consensus from the full set of studies) suggests that it could lead, at a corporate income tax

rate of 40 percent, to leverage ratios being 10 percentage points higher than under a system

which was neutral between debt and equity.

22

Similarly, Feld et al (2013) (as cited in

18

OECD (2011), “Pension Funds Investment in Infrastructure: a Survey”, accessible at

http://www.oecd.org/futures/infrastructureto2030/48634596.pdf. See also forthcoming OECD report to the G20,

“Regulation of Insurance Company and Pension Fund Investment” (2015).

19

Ayala, D., M. Nedeljkovic, C. Saborowski, (2015) “What slice of the Pie? The Corporate Bond Market Boom in

Emerging Economies”, IMF Working Paper, WP/15/148

20

The relative treatment of interest and equity income under the personal income and withholding taxes also needs to be

taken into account, and in some cases may offset the asymmetry at the corporate level.

21

Langedijk, S, G Nicodeme, A Pagano and A Rossi (2015) "Debt bias in corporate income taxation and the costs of

banking crises", VOX, CEPR’s policy portal, accessible at

http://www.voxeu.org/article/corporate-debt-bias-and-cost-

banking-crises

22

de Mooij (2011), “The Tax Elasticity of Corporate Debt: A Synthesis of Size and Variations,” IMF Working Paper 11/95

12

Langedijk et al (2015)) predict that each one percentage-point increase in the corporate tax

rate increases the debt-to-assets ratio by 0.27 percentage points.

Policy makers in several countries, increasingly conscious of these distortions, have adopted a

range of measures to mitigate or address them. Action 4 of the G20-OECD Base Erosion and

Profit Shifting (BEPS) project limiting base erosion via interest deductions aims at addressing

profit shifting using interest.

23

This is, however, not always intended to address the basic tax

asymmetry that gives rise to debt bias. To address debt bias, some countries have simply

adopted limits on the interest expense that can be deducted, perhaps relative to current

earnings

24

and a few have provided an ‘Allowance for Corporate Equity’ (ACE) that eases the

asymmetry by also providing a deduction for the cost of equity finance.

25

Countries typically

limit interest deductions and only a few provide an allowance for corporate equity. However,

in the past, such policy responses have been divergent and often ad hoc.

Annex C on ‘The Role of Taxation in Shaping Corporate Liability Structures’ elaborates on

this issue, including on the implications for financial stability.

c. Public disclosures

No evidence is available that public disclosure requirements are a significant factor in

corporate decisions about whether liabilities they issue should be in the form of debt or

equity.

26

The IOSCO annex International Policies for Public Disclosure- Corporates as Public Issuers

of Debt and Equity Securities (Annex D) outlines the steps taken by securities regulators to

enhance transparency for both equity and corporate bond issues. Over time IOSCO has

provided more guidance to regulators on issuers’ disclosure of information to investors in the

public capital markets.

27

The disclosures that a securities regulator requires are intended to give investors information

that is timely, material and not misleading about a company and its circumstances (for

example, issuer domicile, size, industry, number of securities holders). As equity represents

an interest in the residual profits of a company, the pricing of equity may, more keenly than

23

The BEPS report on Action 4 is expected to recommend a consistent and comprehensive approach to limiting interest

deductibility in order to address BEPS risks.

24

For example, in the European Union, several reforms were undertaken in 2012 and 2013 to address the debt bias in

corporate taxation. “These measures mostly tended to restrict the level of deductible interest. France and Portugal

restricted the deduction of interest payments above a threshold of EUR 3 million. In France, the limit is 85% (75% from

2014) of interest paid, while in Portugal it is 70% of profit obtained before depreciation, net financing expenses and taxes

from 2013, falling to 30% in 2017. Spain and the Netherlands revoked their thin capitalisation rules and introduced new

rules on the non-deductibility of certain interest expenses (a so-called earning stripping rule). Spain, Sweden and Finland

limited the scope of deductibility of interest expenses on intra-group loans. In contrast, Hungary introduced a cash-flow

tax for small companies, which in practice allows immediate expensing of all financing costs.” (For details, European

Commission (2013), Tax Reforms in EU Member States: Tax Policy Challenges for Economic Growth and Fiscal

Sustainability, European Economy 5, 2013)

25

These countries include Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Croatia, Italy and Latvia.

26

Companies may face differing disclosure requirements for public offerings and for private offerings (The latter is an

increasing form of issuance for some EMDE corporates.)

27

See IOSCO Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation, June 2010, available at:

https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD323.pdf

13

debt, depend on disclosures made that provide information relevant to future profits. On the

other hand, the pricing of debt may be particularly sensitive to disclosures about the issuer’s

cash flow and liquidity in the timeframe that the debt service is required.

d. Accounting requirements

Issuers prepare the financial statement element of their financial information disclosures in

accordance with a set of accounting standards, such as national accounting standards or

International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). IFRS contain standards that address how

an issuer should recognise, measure and present its outstanding debt and equity in its balance

sheet, as well as disclose information about each in the footnotes to its financial statements.

Accounting standards also contain provisions for distinguishing between financial liabilities

and equity in financial statements. Under IFRS a liability is defined as “a present obligation of

the entity arising from past events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow

from the entity of resources embodying economic benefits”, and equity is “the residual

interest in the assets of the entity after deducting all its liabilities”.

28

The IASB is aware that

these definitions, and the more detailed requirements in IAS32 “Financial Instruments:

Presentation”, are not always applied in in a way that results in a consistent distinction

between equity and non-equity instruments. The IASB has a project underway to reassess

these treatments, but it is at an early stage of development.

Particular challenges in reassessing these treatments arise from instruments that include both

some characteristics of debt and some characteristics of equity. It is challenging to determine

whether these instruments (or components of them) are best classified as liabilities or as

equity. It is also important to ensure sufficient disclosure of the characteristics of these

instruments, regardless of how they (or their components) are classified. The classification of

these instruments, and the nature of disclosures about them, have implications for collating

data and statistics about corporate funding structures.

Accounting standards help to elicit historical financial information that addresses users’

objective to be able to assess the amount, timing and uncertainty of future cash flows, and the

information needs of debt and equity investors are converging. In an environment where the

disclosure requirements are similar, disclosure requirements are unlikely to have a significant

effect on companies’ decisions on whether to opt for debt or equity finance. However, the

need for market transparency, and costs of disclosures, can be reasons for some privately-

owned companies to avoid issuing publicly-traded securities at all (whether it be debt or

equity). In such cases, companies may opt instead for bank borrowing or private debt issues.

e. Bank capital requirements

No evidence is available that bank capital requirements are a significant factor in corporate

decisions about whether liabilities they issue should be in the form of debt or equity.

Nevertheless, it is possible that recent regulatory reforms (e.g. Basel III framework, the

Dodd-Frank Act in the US and the Banking Union in the EU) may indirectly have an impact

28

IFRS Conceptual Framework 4.4(b) and 4.4(c). The definition in the US FASB Framework is similar

14

on the decision making process of corporates when choosing between equity or debt

financing, as well as when choosing between bank versus market debt.

Within the banking sector, in December 2014 the Basel Committee issued, as part of its

reforms to the capital framework, a consultation paper on proposed revisions to the

standardised approach for measuring credit risk in the capital framework.

29

The revisions to

the standardised approach are, inter alia, intended to improve the granularity and risk

sensitivity of the framework, reduce the reliance on external ratings and improve the

alignment with exposures risk weighted under the internal ratings-based approach.

To enhance the risk sensitivity of the current standardised approach as set forth in Basel II,

30

the Basel Committee has proposed to introduce a specific treatment for corporate equity

exposures involving higher capital requirements than corporate senior debt exposures.

31

This

would be consistent with other parts of the capital framework which recognise that equity

investments are riskier than debt.

These proposals are still under consultation, and therefore cannot explain the observed

increase in leverage since the crisis; moreover many other factors than regulation affect

banks’ demand for corporate instruments. In addition, given that banks are not typically

major holders of nonfinancial corporate equity, the impact of changes in bank regulation on

the future cost of equity is likely to be negligible.

3. Financial Stability Concerns

Expanding corporate bond markets indicate a deepening and diversification of capital markets

with overall benefits for funding of the real economy. However, financial stability concerns

29

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Consultative Document. “Standards: Revisions to the Standardised Approach

for Credit Risk”, March 2015. Accessible at http://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d307.pdf

30

The current standardised approach for credit risk is set out in Basel II: International Convergence of Capital Measurement

and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework – Comprehensive Version, June 2006. Accessible at

http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.pdf

.

The current risk weighting for corporate exposures using the standardised approach to calculate regulatory capital

requirements is based upon the external rating of the corporate borrower with risk weights ranging from 20% for AAA to

AA- rated corporates, to 150% for corporates rated below BB-. Unrated corporates – and this constitutes the vast majority

of corporate borrowers – are assigned a risk weight of 100%.

In the current standardised approach equity investments in other banks are risk weighted at either 100% or 250%.

However, a distinct treatment for equity issued by corporates is not prescribed (as opposed to the internal ratings-based

approach, where either bank or corporate equity receive a specific treatment).

31

The proposed rules might still be subject to substantial change since the consultative document mentioned that the Basel

Committee has not ruled out introducing a limited role for external ratings (e.g. to distinguish between investment and

non-investment grade) in the final version. Also, the consultative document mentioned that proposed risk weights were

only for indicative purposes.

Under the proposed revisions to the standardised approach:

- The risk weighting of senior corporate borrowings (i.e. debt) are based upon two risk drivers: revenue and leverage,

with indicative risk weights ranging from 60% to 130%. Exposures to firms with negative equity will be risk

weighted at 300%; and,

- Equity exposures would be risk weighted 300% if the firm is publicly listed and 400% for all other firms. This

approach would align the treatment for equities with that of the simple risk-weight method in the internal ratings-

based approach

15

may arise in instances where overall debt levels are high and the credit quality of nonfinancial

corporate debt has declined.

• Recent increases in corporate debt levels and lower debt-servicing capacity in certain

countries have raised the sensitivity of these corporates to macroeconomic and

financial shocks.

32

High private-sector debt levels can also negatively impact

economic growth

33

, thus potentially reinforcing recessions and hampering recovery.

• The continuing low interest rate environment may lead to excessive upward pressures

on bond prices which – together with declining underwriting standards – could lead to

the build-up of a “bond bubble” (and therefore at some point the risk of a sharp and

disorderly reversal). There could be value in undertaking further work on the

investment objectives and horizons of investors in corporate bonds in this

environment.

• Given the rapid development of non-investment-grade debt markets in many countries,

the sensitivity of markets to shocks may be accentuated in some instances by the lack

of investor experience with the performance of lower-rated debt in credit cycle

downturns.

• The strong issuance of debt in foreign currency raises another financial stability issue.

While many jurisdictions and market participants are relatively sanguine about the

extent of this particular risk,

34

a number of jurisdictions lack data to adequately assess

the degree of any currency mismatch, including the degree to which debt-related

currency exposures are hedged through other instruments. As the volume of foreign

currency debt and cross-border investment in debt grows, so does the need for data on

corporate hedging and other derivatives positions as well as financial statements for

non-listed companies (as well as information on the extent to which companies are

developing natural hedges by matching interest expense with revenues in the same

currency).

35

There would be value in further investigating the potential for

development of domestic corporate bond markets or more affordable hedging

instruments.

Impact of debt on corporate fundamentals

After a prolonged period of extraordinarily low funding costs, a risk exists that interest rates

could reverse rapidly at some point, potentially interacting with declining corporate

profitability to increase the financial stress of certain corporate issuers. To some extent tighter

financing conditions have already taken hold in certain emerging markets. Corporate debt

levels relative to both GDP and earnings have steadily increased.

32

See for example Giroud, X., Mueller, H.M. (2015): “Firm Leverage and Unemployment during the Great Recession”,

NBER Working Paper No. 21076, April 2015.

33

Liu, Y. & Rosenberg, C. (2013), “Dealing with Private Debt Stress in the Wake of the European Financial Crisis”, IMF

Working Paper WP/13/44.

34

For details, see Annex E.1.

35

Letter to the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors by IMF/FSB/BIS dated September 11, 2014. Accessible

at http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/wp-content/uploads/r_140923b.pdf

16

In the IMF’s note (Annex A), a sensitivity analysis is conducted looking at the simultaneous

impact of increasing borrowing costs, declining earnings and exchange rate depreciation on

EMDE corporate borrowers’ “debt at risk” (which IMF defines as the debt of firms with

interest coverage ratios below 1.5). This exercise finds that the combination of these shocks

can lead to a material increase in “debt at risk” among EMDE borrowers, particularly in

jurisdictions with high levels of foreign-currency denominated debt and fewer natural hedges

(e.g. export earnings in FX).

The World Bank paper (Annex B) reinforces this point. It notes that pro-cyclical investor

behaviour can have systemic implications for EMDEs once the global cycle winds down or

when global shocks occur. Large foreign currency exposures raise risks, particularly for

unhedged issuers, and the recent rapid strengthening of the US dollar against most EMDE

currencies may already have increased strains for some borrowers. In this context, the

inevitable exit from extraordinary monetary policies will tighten international funding

conditions, which could prove disruptive for EMDE currencies, balance sheets, and funding

capacity. Additionally, fragility in EMDEs can be further compounded by the concentration

of foreign investors in their growing but still relatively shallow local financial markets.

Bank exposures

Corporate fragility can have important knock-on effects on the banking sector. First of all, as

the OECD-IMF paper (Annex C) sets out, if debt is preferred over equity and debt is

primarily channelled through the banking system, debt bias increases the size of bank loan

books. In addition, the IMF paper (Annex A) notes that weaknesses in the corporate sector

could put pressure on banks’ asset quality. In particular, across a sample of 15 major EMDEs,

sensitivity analysis illustrates that a 15% default on the total debt at risk owed to banks would

lead to a significant deterioration in banks’ buffers – defined as Tier 1 capital and

provisioning – in more than half the countries. And in about a quarter of cases, these buffers

would appear particularly low, when benchmarked against Basel III’s minimum capital

requirements (including the capital conservation buffer requirement)

In some EMDEs (as well as advanced economies) corporate deposits have increased steadily

over the past few years. A BIS paper (Annex E.3) suggests that another channel of corporate

spill-over on banks could be through the impact of the withdrawal of corporate deposits on

local banks’ funding, especially if these banks have come to rely on corporate deposits for

part of their wholesale funding. Deposits from corporates exploiting the “carry” between local

and foreign currency interest rates could be withdrawn if the carry positions are unwound

when interest rate differentials narrow or market volatility increases. Deposits that are

denominated in foreign currencies, in turn, tend to be more pro-cyclical than other types of

deposits and may thus be subject to sudden withdrawals by corporates facing roll-over risks.

Debt and broader market liquidity concerns

High corporate debt levels can act on financial stability both directly through credit cycle

downturns and defaults, and indirectly through market channels and mark-to-market losses. A

key concern amongst policy makers is that secondary market liquidity in bond markets has

declined, and that in times of stress this could exacerbate price movements and lead to

outsized losses for market participants. (In such stress periods, market participants may find

that they are only able to sell those of their assets that are most liquid; so, for instance, selling

pressure in EMDE markets may be concentrated in larger countries with more liquid assets.)

17

Work done by the BIS suggests that both cyclical and structural components have contributed

to this reduction in secondary market liquidity. Market-making practices have changed,

putting upward pressure on bid-ask spreads and trading costs and resulting in concentration of

liquidity into a narrow set of instruments at the expense of others.

From a policy perspective, however, a key question is whether the trends underway in market-

making are consistent with robust liquidity at times of stress, i.e. the times when liquidity is

most needed. If the trends are consistent, then the price of market-making services should rise

in normal times to account for the higher costs of liquidity in bad times. Admittedly, price

realignments are unlikely to prevent an exceptionally large shock from bringing financial

markets to a halt. But by properly pricing liquidity risk, price realignments should encourage

financial behaviour that takes market liquidity into account and does not naively rule out an

eventual price collapse, especially when excesses are building up. By reducing market

participants' vulnerability to ordinary liquidity shocks, this would make it less likely that such

shocks could feed on themselves and undermine system-wide liquidity.

At the same time that the nonfinancial corporates have expanded their market-based

borrowing, asset managers, through the investment funds they manage, have become a

relatively larger part of the investor base. The potential financial stability risks emanating

from the asset management industry have been discussed in the IMF’s April 2015 Global

Financial Stability Report. The FSB also has work underway to assess the financial stability

issues related to asset management and the potential for a disorderly bond market sell-off in

the current environment and will report to the G20 later this year.

Data gaps

The IMF-FSB-BIS report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors in

September 2014 on data gaps involving foreign exchange exposures included key messages

from a workshop jointly held by the BIS Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS)

and the FSB Standing Committee on Assessment of Vulnerabilities (SCAV) on currency

mismatches and leverage in corporate balance sheets. The key messages of this workshop (see

Annex E.1) were: that EMDE corporate leverage was rising; that increasing use of bond

markets may have shifted duration risk to institutional investors; and that the unavailability of

consistent granular data might mask the concentration of risk in particular sectors or

institutions.

The two main data gaps identified by the workshop participants were, first, in corporate

hedging activities and other derivatives positions; and second, in the availability of financial

statements for non-listed companies. The workshop summary includes suggestions for a

number of approaches that could help to fill these data gaps.

Structural versus cyclical factors

The financial stability concerns outlined above may have both cyclical and structural causes,

as follows:

Leverage: Much of the increase in debt likely results from the very low interest rate

environment, which is clearly cyclical (unless the low interest rate environment is the “new

normal,” in which case this could be considered structural). In addition, bank deleveraging

has contributed to the increased bond issuance, and this deleveraging has both cyclical

(cleaning up balance sheets post-crisis) and structural (new regulations making lending more

18

capital intensive) components. Other key elements behind increased leverage have been

financial deepening in EMDEs and the tax advantages of debt financing, both of which are

structural.

Possible asset price bubbles: This owes, in part, to investors searching for yield and moving

towards higher-yielding assets. The source of the search for yield is related to the very low

risk-free rates that resulted from extraordinary monetary policy and hence is cyclical.

However, to the extent that the increased demand for some bonds is driven by regulation that

has driven up the demand for high-quality liquid assets, there are structural elements as well.

Pro-cyclicality: If short-term investors increase their involvement in the corporate debt

market, this can increase the market’s vulnerability to pro-cyclicality. To the extent that

money has flowed to emerging market assets as a result of a search for yield, this represents a

cyclical factor.

Currency mismatch: To the extent that the currency mismatch present in some cases has been

driven by the ease of issuing debt denominated in foreign currencies in the current

conjuncture, this would be cyclical. However, another reason to issue debt in foreign

currencies is because of a lack of depth in domestic markets, which is a structural cause.

Interconnectedness: One source of increased interconnectedness can come from a form of

carry trade whereby corporates raise funds abroad and deposit those funds in the domestic

banking system. This could be cyclical to the extent it is driven by a search for yield, but it

also has structural causes to the extent that stable exchange rate regimes facilitate this type of

carry trade. In addition, a bias toward debt financing makes firms more reliant on banks than

they otherwise would be, and this is a structural cause of interconnectedness.

Data gaps: Data gaps are a structural concern, although the concern is exacerbated when debt

issuance goes up, which can have cyclical causes.

4. The Potential Role of Macroprudential Policies in Addressing

Financial Stability Concerns

36

As noted in the FSB-IMF-BIS progress report to the G20 on Macroprudential Policy Tools

and Frameworks

37

, macroprudential policy is characterised by reference to three defining

elements:

(i) Its objective: to limit systemic risk – the risk of widespread disruptions to the

provision of financial services that have serious negative consequences for the economy at

large.

(ii) Its scope: the focus is on the financial system as a whole (including the interactions

between the financial and real sectors) as opposed to individual components (that take the rest

of the system as given).

36

This is based on “Staff Guidance Note on Macroprudential Policy—Detailed Guidance on Instruments” prepared by IMF

staff and completed on 6 November 2014. Accessible at http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2014/110614a.pdf.

37

http://www.financialstabilityboard.org/2011/10/r_111027b/, 27 October 2011.

19

(iii) Its instruments and associated governance: it uses primarily prudential tools calibrated

to target the sources of systemic risk. Any non-prudential tools that are part of the framework

need to clearly target systemic risk.

To mitigate any financial stability risks from corporate liability structures, policymakers could

explore the use of macroprudential tools—including tools specifically targeted at corporate

credit as well as at foreign exchange risks—to complement other policy measures. Currently,

most of the tools available fall under the purview of bank supervisors. The tools vary by

jurisdiction, and any decisions over the use of such tools would need to take into account

national economic and financial conditions, including whether the type of corporate financing

(e.g. bank or market based) appear to present systemic risks.

Tools that target corporate credit

If strong growth in bank lending to the corporate sector is generating systemic risks,

macroprudential authorities could consider raising capital requirements on banks’ lending to

firms, e.g. by increasing risk-weights on these exposures, or by imposing countercyclical

capital buffers. The build-up of additional capital buffers could increase banks’ resilience to

corporate credit shocks, while these measures may at the same time restrain the growth in

bank credit to the corporate sector. If such capital measures are not expected to be sufficiently

effective in containing systemic risk, caps on the growth rate of new credit or the share of new

corporate loans in total new loans could also be considered. Indirectly, when they incentivise

banks to ration out less creditworthy borrowers, caps on credit growth can also help improve

banks’ underwriting standards.

Any use of such tools would need to be carefully assessed and calibrated. Applying broad

measures on corporate credit can restrict credit growth to industry sectors that are receiving

too much credit, but may also further restrict credit to industry sectors already experiencing a

downturn or receiving insufficient credit. Such caps could also have spill-over effects by

leading banks to increase credit instead to other sectors (e.g. the consumer sector).

Tools that target foreign exchange loans

The credit risk associated with firms with large foreign currency debts is significantly higher,

particular for those without “natural” hedges. In addition, banks that lend in foreign currency

can also be exposed to roll-over risks if there is a maturity mismatch with the underlying

financing, e.g., if medium- or long-term foreign currency loans are financed by short-term

foreign currency borrowing from abroad. To alleviate credit risks, targeted macroprudential

policy measures such as higher risk-weights, and outright limits, on banks’ lending in foreign

currency can help, while recognizing that excessive flexibility in use of risk weights could

impair predictability.

38

The extent to which these tools can differentiate effectively between

hedged and unhedged corporate borrowers will depend on the availability of information and

supervisory capacity. These areas should be strengthened to enable well-informed and prudent

decisions regarding the risks involved in foreign currency borrowing.

If de facto dollarisation is widespread, other structural tools should be considered alongside

tighter macroprudential measures. These would include ensuring sound macroeconomic

38

Here, as with other type of tools, use of macroprudential measures needs to be consistent.

20

policy frameworks; encouraging the development of domestic financial markets in domestic

currency; and a shift of public sector borrowing in foreign currency to domestic currency.

Tightly calibrated macroprudential tools that may complement these measures include limits

on net open position in foreign exchange; differentiated reserve requirements across

currencies; or liquidity requirements differentiated by currency.

Potential leakages

As noted, most of the current tools available for addressing systemic risks arising corporate

credit fall under the purview of bank supervisors. In implementing macroprudential policies in

the banking sector, macroprudential authorities should be mindful of the potential leakages

that could arise when corporate borrowers substitute domestic bank credit with borrowing

from unregulated financial institutions or domestic capital markets (domestic leakages), as

well as borrowing from abroad (cross-border leakages). These leakages can constrain the

effectiveness of policies. In particular, while the intended increase in resilience for the

banking sector from higher capital requirements can be preserved, leakage can make it

difficult for authorities that seek to constrain the build-up of leverage in the corporate sector

to effectively achieve that goal.

Containing these leakages can be particularly challenging in countries where capital markets

are well-developed and where corporate borrowers have access to alternative sources of

credit. Where credit is being provided by non-banks, such as dedicated leasing companies, or

other non-bank finance companies, domestic leakages can be reduced by extending the

regulatory perimeter to unregulated entities. (One such example of extending the perimeter

would be, in the case of non-banks related to banks, expanding the scope of prudential

requirements so as to consolidate such activity.) However, containing corporate leverage can

be more difficult where market-based funding, such as through corporate bond issuance, is

readily available. Macroprudential authorities should ensure that banks have sufficient capital

to ensure resilience to corporate credit shocks, but tools need to be well calibrated;

inappropriate and untimely usage of macroprudential tools to restrict corporate credit could

incentivise more leakage and exacerbate the risks.

Strategies to address cross-border leakages can include reciprocity arrangements; greater host

control; and in certain circumstances, targeted capital flow management measures (CFMs).

39

Reciprocity on risk weights for corporate exposures is currently not subject to international

agreement, and may be difficult for countries with well-developed capital markets, but some

host authorities are actively pursuing cooperation with other national authorities on the

implementation of higher risk-weights and counter-cyclical capital buffers. Greater host

control includes encouraging or requiring banks that are foreign affiliates to be established as

subsidiaries, subject to countries’ rights and obligations under international agreements

including GATS and the OECD Codes of Liberalisation, in order to subject them to capital

regulation and/or caps on credit growth.

39

Measures that are both capital flow management and macroprudential measures can have a role in supporting both

macroeconomic policy adjustment and safeguarding financial system stability in certain circumstances. These include

circumstances: (i) where the room for adjusting macroeconomic policies is limited, (ii) where the needed policy steps

require time, or when the macroeconomic adjustments require time to take effect, (iii) where an inflow surge raises risk

of financial system instability, or (iv) where there is heightened uncertainty about the underlying economic stance due to

the surge. However, such measures should not be used as substitutes for warranted macroeconomic adjustment.

21

The use of targeted CFMs needs to be in line with established principles ((IMF (2012); IMF

(2015))

40

and OECD (2015)

41

, and emphasis should be given to lengthening the maturity of

corporate debt issuance and reducing the reliance on FX borrowing. As an alternative or

additional measure, policies that correct the tax bias favouring debt would reduce corporate

demand for credit and help mitigate the risks from excessive corporate leverage.

The need to consider benefits and costs

In implementing these measures, macroprudential authorities need to strike a balance between

ensuring the effectiveness of these tools in securing financial stability, and the need to

maintain the efficient provision of financial services so as not to jeopardize economic growth

and development. This implies a need to calibrate these macroprudential measures carefully

and in a manner that takes account of country circumstances and the phase of the credit cycle.

Where stability risks are rising in the upswing of the credit cycle, macroprudential authorities

should consider tightening macroprudential tools. Where these risks have receded, or financial

stress materializes, these measures could be relaxed to encourage credit growth to support

economic activities. To guide the calibration of macroprudential tools, bank and corporate

balance sheet indicators should be used along with market and credit flow indicators.

5. Possible next steps

There is evidence that corporate debt levels relative to GDP are increasing in many countries.

While in many cases this may represent welcome financial deepening, in some cases this

could adversely affect financial stability. Prudential regulations are aimed at controlling the

financial risks to banks from corporate exposures. Basel Committee capital standards require

banks to hold capital in proportion to credit risk, and the ongoing review of the standardised

and internal-model approaches aim, among other things, to improve the risk-sensitivity of

current standards. Prudential supervisors also regularly require stress tests of banking assets

(including for corporate exposures). Furthermore, accounting standard setters (both the IASB

and US FASB) are introducing expected loss approaches to provisioning that will require

more forward-looking provisions that have regard to wider macroeconomic factors. All of

these changes to regulation could result in some banks being required to raise additional

capital and should have the effect of mitigating potential adverse effects on financial stability

that might arise via banking sector exposures to corporate loans.

However, better tools are needed to monitor for, and to address, any excessive corporate debt

accumulation that may be adding to systemic risks, and there could also be value in further

examining whether there are incentives that may artificially favour debt over equity and,

where necessary, removing any such incentives. Possible measures that could be further

discussed by the FSB and G20 Ministers and Governors include:

40

IMF (2012), “The Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows – An Institutional View”, November 2012.

Accessible at http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2012/111412.pdf

, IMF (2015), “Measures which are Both

Macroprudential and Capital Flow Management Measures: IMF Approach” April 2015. Accessible at

http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2015/041015.pdf.

41

OECD (2015), “The OECD’s Approach to Capital Flow Management Measures used with a Macro-prudential Intent” –

Report to G20 Finance Ministers”, April 2015. Accessible at

http://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/trade-and-investment/G20-

OECD-Code-Report-2015.pdf

22

• Filling data gaps: Information on corporate sector exposures, while not costless to

collect, is essential for policy makers to assess the risks and develop policies

accordingly. The CGFS/SCAV workshop noted that regular reporting of more

consistent and granular data would enable more effective monitoring of the liability

structure of the corporates, the extent of foreign currency hedging and other

derivatives positions, as well as data on non-listed companies. In the meantime,

supervisors should use existing data to monitor foreign currency exposures and detect

emerging vulnerabilities.

• Addressing the debt-equity tax bias: The clear evidence of a sizeable tax bias

toward debt financing raises evident financial stability concerns. While there is

growing concern with the problems caused by the asymmetric tax treatment of debt

and equity, the significance of this bias has not been assessed, and there is no

consensus on how best to address it. The IMF/OECD paper notes that a pragmatic

response to address this bias is to extend rules limiting excessive interest deductions as

proposed in the G20/OECD BEPS Project, although interest limitation rules may

generally be more focussed on addressing debt shifting than the asymmetry at the

heart of the debt bias. While some countries have enacted an ‘Allowance for

Corporate Equity’ (ACE), such an approach needs careful design to address concerns

about revenue cost and potential for tax avoidance. In navigating these complex

issues, policy makers would benefit from a careful review of the significance of tax

distortions for financial stability and of the effectiveness of the different approaches

that have been, or might be adopted (unilaterally or in cooperation).

• Macroprudential policy tools to address the conjunctural factors: To mitigate the

risks presented by this rapid growth of corporate leverage, particularly in foreign

currency, national policymakers should explore the use of macroprudential tools to

mitigate such risks taking into account the likely benefits and costs to the financial

system and different national economic and financial conditions (as described in

section 4 above).

• Potential further work in 2016: There could be value to further work including on: i)

further analysis of data on nonfinancial corporate leverage to examine the extent to

which particular economic factors drive the liability structure choices of different

types of corporates and whether any financial stability concerns arise from these, ii)

existing country experiences with the use of macroprudential tools used to address

risks arising from corporate debt financing, iii) country-specific case studies on

addressing the debt-equity tax bias.

23

List of contributions by International Organisations annexed to this paper

A IMF paper Analysis of Balance Sheet Risks in Emerging Market Corporates

B World Bank paper Global Liquidity and External Bond Issuance in Emerging Markets and

Developing Economies

C IMF-OECD paper The role of taxation in corporate liability structures

D IOSCO paper International Policies for Public Disclosure - Corporates as Public Issuers

of Debt and Equity Securities

E BIS papers Risks related to EME corporate balance sheets: the role of leverage and

currency mismatch; Nonfinancial corporations from emerging market economies and

capital flows; and Summary: Joint CGFS – FSB-SCAV workshop on risks from currency

mismatches and leverage on corporate balance sheets

24

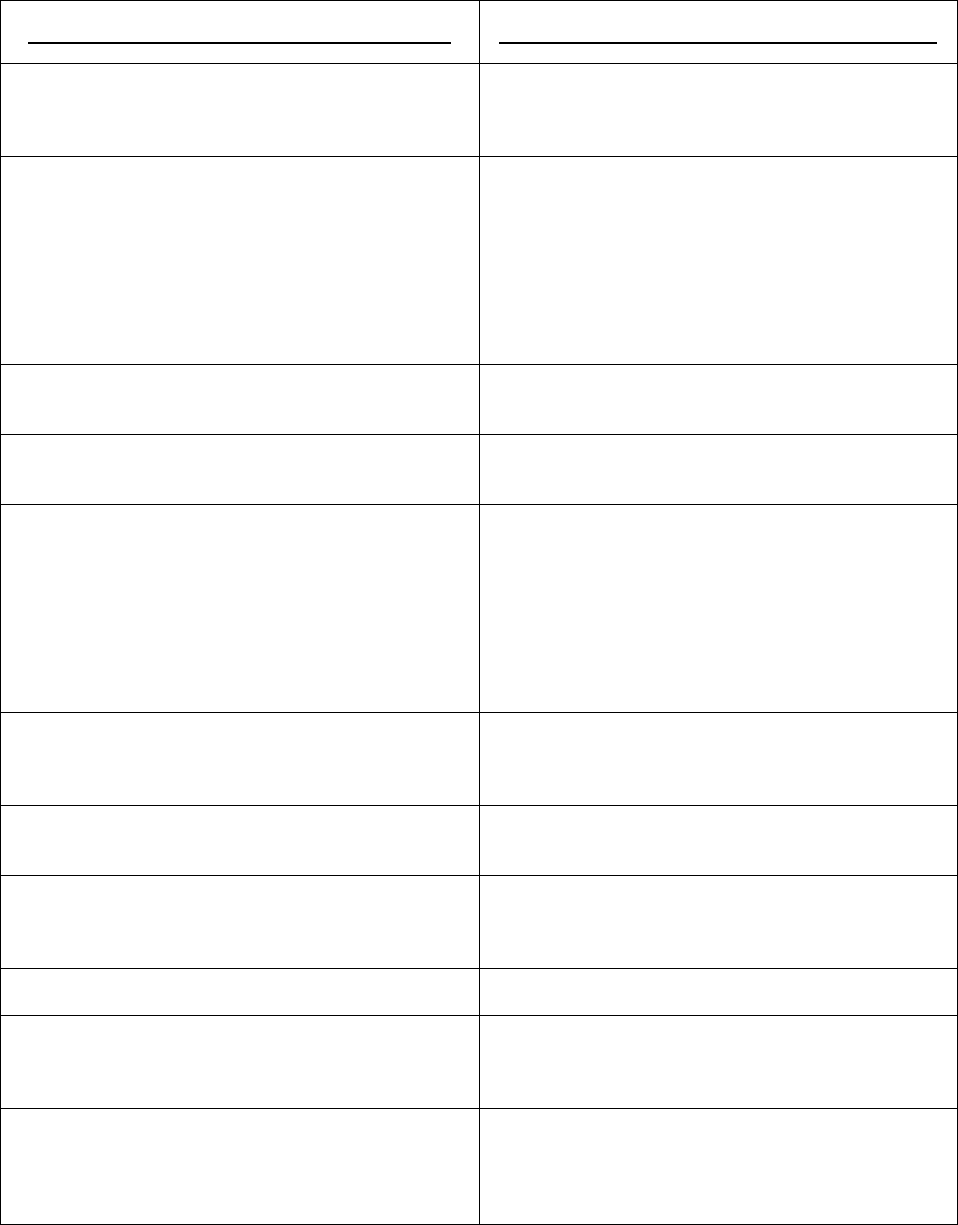

Total debt by sector (excluding the financial sector)

As a percentage of GDP

Table 1

Level in 2014 Change since end–2007

1

House–

hold

Corpo–

rate

Govern–

ment

2

Total House–

hold

Corpo–

rate

Govern–

ment

2

Total

Advanced

economies

3

74 89 96 259 –4 4 32 32

United States

78 68 88 235 –17 1 38 21

Japan

66 103 209 379 0 4 59 62

Euro area

61 103 92 257 2 6 25 33

France 56 122 95 273 10 18 30 58

Germany 55 55 75 185 –8 0 10 2

Italy 43 79 132 254 6 6 30 43

Netherlands 113 124 68 305 4 –1 24 28

Spain 73 114 96 284 –7 –8 59 44

Australia

116 75 30 221 10 –3 22 29

Canada

93 103 64 260 17 14 15 46

Hong Kong SAR

64 218 5 287 13 87 3 103

Korea

83 104 38 225 11 14 14 43

Singapore

60 80 99 239 21 24 12 57

Sweden

83 166 41 290 19 36 1 56

Switzerland

120 90 34 245 12 19 –6 25

United King

dom 88 77 88 253 –7 –9 46 30

Emerging markets

3

26 88 42 156 10 33 2 44

Argentina

6 10 43 59 2 0 –4 –2

Brazil

4

25 47 62 134 12 19 –2 29

China

35 154 41 230 16 53 6 76

India

9 51 66 126 –2 9 –9 –1

Indonesia

17 22 25 64 6 8 –9 5

Malaysia

4

68 62 53 183 13 0 11 25

Mexico

15 21 33 69 2 7 12 21

Russia

4

19 50 15 86 8 10 5 26

Saudi Arabia

11 37 2 50 –1 4 –19 –16

South Africa

38 33 53 123 –4 –1 20 16

Thailand

68 50 30 148 23 4 7 34

Turkey

21 51 34 106 10 27 –8 29

1

In percentage points of GDP.

2

BIS Credit to the government at nominal values except for Korea for which only market values are

available.

3

Weighted averages of the economies listed based on each year GDP and PPP exchange rates.

4

Breakdown of household

debt and corporate deb

t is estimated based on bank credit data.

Sources:

IMF, World Economic Outlook; OECD; national sources; BIS database on total credit.

25

Total debt by sector (excluding the financial sector)

As a percentage of GDP

Table 2

Level in 2014 Change since end–1999

1

House–

hold

Corpo–

rate

Govern–

ment

2

Total House–

hold

Corpo–

rate

Govern–

ment

2

Total

Advanced

economies

3

74 89 96 259 14 9 34 56

United States

78 68 88 235 13 7 40 59

Japan

66 103 209 379 –8 –27 103 68

Euro area

61 103 92 257 13 22 19 54

France 56 122 95 273 22 31 33 86

Germany 55 55 75 185 –15 2 14 1

Italy 43 79 132 254 23 27 19 69

Netherlands 113 124 68 305 39 3 5 51

Spain 73 114 96 284 33 48 33 114

Australia

116 75 30 221 50 13 9 73

Canada

93 103 64 260 31 11 –12 30

Hong Kong SAR

64 218 5 287 6 108 5 119

Korea

83 104 38 225 36 –3 28 57

Singapore

60 80 99 239 23 6 13 41

Sweden

83 166 41 290 37 70 –24 83

Switzerland

120 90 34 245 14 11 –16 11

United King

dom 88 77 88 253 22 9 46 76

Emerging markets

3

26 88 42 156 17 39 –15 37

Argentina

6 10 43 59 0 –10 9 –1

Brazil

4

25 47 62 134 16 20 5 41

China

35 154 41 230 25 56 3 84

India

9 51 66 126 3 28 –4 27

Indonesia

17 22 25 64 … … … …

Malaysia

4

68 62 53 183 … … 15 –17

Mexico

15 21 33 69 6 0 11 17

Russia

4

19 50 15 86 18 22 –99 –54

Saudi Arabia

11 37 2 50 3 9 –101 –89

South Africa

38 33 53 123 6 5 –1 7

Thailand

68 50 30 148 19 –45 11 –24

Turkey

21 51 34 106 19 29 –9 –20

1

In percentage points of GDP.

2

BIS Credit to the government at nominal values except for Korea for which only market values are

available.

3

Weighted averages of the economies listed based on each year GDP and PPP exchange rates.

4

Breakdown of household

debt and corporate debt is estimated based on bank credit data

.

Source

s: IMF, World Economic Outlook; OECD; national sources; BIS database on total credit.

Balance Sheet Risks in Emerging Market Corporates

International Monetary Fund—Monetary and Capital Markets Department (MCM)

1

August 12, 2015

Contents Page

I. Rising Vulnerabilities .............................................................................................................1

II. Sensitivity Analysis ...............................................................................................................5

III. Impact On Banks..................................................................................................................8

IV. Policy Implications ..............................................................................................................9

Appendix 1. Methodology for Corporate Sensitivity Analysis ...............................................10

I. RISING VULNERABILITIES

Corporate debt issuance in major emerging market countries has risen sharply in recent years,

against the backdrop of ample global liquidity and prolonged low global interest rates. New

corporate bond issuance rose 10 percent in 2014, with Asia leading other regions (Figure 1).

Issuance in foreign currency amounted to one fifth of total issuance over the last five years,

growing at a compounded annual rate of 15 percent during the period. Sectors such as