Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress

CRS Report for Congress

Received through the CRS Web

Order Code RL32025

Iraq’s Trade with the World:

Data and Analysis

Updated September 23, 2004

Vivian C. Jones

Analyst in International Trade and Finance

Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division

Iraq’s Trade with the World: Data and Analysis

Summary

In the last 25 years, Iraq’s economic involvement in the world market has

fluctuated dramatically — fluctuations brought about, in part, by damage to its oil

infrastructure during the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, followed by a multinational

military response and years of multilateral economic sanctions as a result of its 1990

invasion of Kuwait.

Economic stability in Iraq has depended on exports of crude oil since the end

of World War II. Exports of oil accounted, on average, for 83% of Iraq’s annual

exports from 1980-1990 and virtually all exports since 1996. When international

economic sanctions were imposed in August 1990, Iraq’s oil sales dropped from

$10.2 billion in 1990 to $305 million in 1991. From 1991 to 1995 the regime of

Saddam Hussein declined to accept United Nations (U.N.) proposals seeking to

permit Iraq to sell limited quantities of oil to meet the needs of its people. Without

oil export revenues, living conditions in the country deteriorated sharply.

In 1996, the Iraqi government agreed to the establishment of a United Nations-

administered Oil-For-Food Program (OFFP) that has allowed the Iraqi government

to export limited amounts of oil and import food and humanitarian supplies under

close supervision. On May 22, 2003, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution

1483, lifting all civilian trade sanctions on Iraq, providing for the termination of the

OFFP.

Since Iraq’s chief export product is crude oil, the country’s economic future, at

least in the short term, will depend on its ability to tap into its vast oil resources.

According to U.S. Department of Energy statistics, Iraq has 112 billion barrels of

proven oil reserves, and possible reserves of as much as 220 billion barrels. Due to

years of war combined with the excesses of the Hussein regime, its oil potential has

been largely unexplored and only 17 of 80 discovered oil fields have been developed.

Despite concerns over continued insurgent activity and the stability of the

interim government that have scared away much foreign investment by major

corporations, the Bush Administration officials and others report that Iraq’s economy

is booming. The U.S. government is engaged in efforts to attract small and medium

U.S. businesses to work and invest in the country as subcontractors on U.S.

government contracts and in the private sector. The United States has lifted most

international trade sanctions with respect to Iraq in keeping with United Nations

Security Council Resolution 1483, and has designated Iraq as a beneficiary

developing country under the Generalized System of Preferences.

This report provides detailed trade statistics on Iraq’s trade with the world from

1980 to the present, highlighting its major trading partners and regional trade

linkages. Data on U.S. trade with Iraq for 2003 and 2004 to date are also provided.

The report will be updated as events warrant.

Contents

Introduction ......................................................1

Background ......................................................2

Sanctions and the Oil-For-Food Program ...........................3

Iraq’s Exports.....................................................4

Iraq’s Oil Resources............................................6

Condition of Infrastructure...................................7

Post-War Situation.............................................7

Iraq’s Imports.....................................................9

Post-War Situation............................................12

Illicit Trade ......................................................13

Post-War Situation............................................14

Major Trading Partners ............................................14

Pre-War International Interests ..................................15

Russia..................................................15

France..................................................16

United States ............................................17

Asia ...................................................17

Pre-War Regional Trade .......................................18

Jordan..................................................18

Turkey .................................................19

Syria...................................................19

Other Regional Trade......................................19

Post-War Trade and Investment Prospects .........................20

U.S. Economic and Trade Policy.....................................21

Current State of Iraq’s Economy .................................22

Exim Bank and OPIC Facilitation ............................24

Normalizing Trade Relations....................................24

Generalized System of Preferences ...............................26

Conclusion ......................................................27

Appendix: Trade Tables ...........................................28

List of Figures

Figure 1. Iraq’s Oil Exports, 1980 to 2003 ..............................5

Figure 2. Iraq’s Exports of Crude Oil, 1996 to 2003 ......................6

Figure 3. Iraq: Monthly Oil Production and Exports, May 2003-July 2004 ....9

Figure 4. Iraq’s Imports, 1980 to 2003 ................................10

List of Tables

Table 1. Iraq’s Top 10 Exports, 1989 ..................................4

Table 2. Iraq’s Top 10 Imports, 1989 .................................10

Table 3. Iraq’s Major Imports, 1979-1983 .............................11

Table 4. Iraq’s Oil-For-Food Imports by Sector, 1997-2002 ...............12

Table 5. Iraq’s Top 10 Export and Import Trading Partners, 2003 ...........15

Table 6. Top U.S. Imports from Iraq, 2003 and January-July 2004 ..........28

Table 7. Top 30 U.S. Exports to Iraq, 2003 and January- July 2004 .........30

Table 8. Iraq: Top 30 World Export Commodities, 1980-1988 ............33

Table 9. Iraq: Top 30 World Import Commodities, 1980-1988 ............35

Table 10. Iraq: Top 30 World Export Commodities, 1990-2003 ...........37

Table 11. Iraq: Top 30 World Import Commodities, 1990-2003 ............40

Table 12. Iraq’s Major Trading Partners, 1982-2003 .....................43

Table 13. Iraq’s Regional Trade: 1982-2003 ...........................46

1

S/RES/661, August 16, 1990.

2

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, Final Report, July 22,

2004, p. 378-379.

3

Ibid., p. 367.

Iraq’s Trade with the World:

Data and Analysis

Introduction

Iraq’s involvement in world trade has varied dramatically in the last 25 years.

These fluctuations have been caused, in part, by the effects of the Iran-Iraq War

(1980-1988), and the influences of Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait, including a

multinational military response. International economic sanctions were imposed

following the invasion pursuant to United Nations Security Council Resolution 661.

1

From 1996 until the end of the regime of Saddam Hussein, exports and imports were

closely regulated through a U.N.-authorized Oil-For-Food Program (OFFP) that

permitted the Iraqi government to sell limited quantities of oil in order meet the needs

of its people for food and humanitarian supplies. The OFFP officially terminated its

operations on November 21, 2003, in keeping with U.N. Security Council Resolution

1483.

International trade and economic development are essential to Iraq’s recovery

from war, from decades of repression, and from the adverse effects of international

sanctions. Many in Congress and the Bush Administration believe that

reconstructing Iraq, including assisting in the restoration of its economic systems,

is a compelling U.S. national interest. This was emphasized in the final report of the

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (informally

known as the 9/11 Commission). The Commission recommended that “a

comprehensive U.S. strategy to counter terrorism should include economic policies

that encourage development, more open societies, and opportunities for people to

improve the lives of their families and to enhance prospects for their children’s

future.”

2

The 9/11 Commission also cautioned that if “Iraq becomes a failed state,

it will go to the top of the list of places that are breeding grounds for terrorism at

home.”

3

Iraq’s economic success, at least in the short term, is dependent on its ability to

export crude oil, which accounted for 83% of all exports from 1980-1989 and

virtually all exports since 1996. However, continuing insurgent attacks against oil

facilities have reduced post-war oil export flows. Extensive investment in the

rehabilitation of Iraq’s oil facilities is also required before pre-sanctions production

levels are realized and new production can be developed.

CRS-2

4

“Middle East Oil and Gas,” Exxon Background Series, December 1984, p. 12.

5

The $17.5 billion figure is based on trade data collected by the United Nations. The $21

billion figure is based on the International Monetary Fund Direction of Trade Statistics

series.

6

Sluglett, Marion F. and Sluglett, Peter, Iraq Since 1958: From Revolution to Dictatorship,

New York: KPI, p. 265.

This report first provides an analysis of Iraq’s trade with the world from the

Saddam Hussein’s assumption of the presidency in 1999 to the present. Iraq’s

exports (especially its oil resources), primary imports, major trading partners, trade

during the U.N. sanctions period, and alleged illicit trade during that period are

discussed. Second, the report discusses the progress of largely U.S.-driven economic

development initiatives in Iraq, and the continued process of normalizing Iraq-United

States trade relations. Third, an appendix provides comprehensive tables on Iraq’s

exports, imports, major trading partners, and regional trade.

Background

Since the beginning of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 1979, distinct patterns can

be seen in Iraq’s international trade relationship with the world that seem to coincide

with its domestic history. The first pattern corresponds to the beginning of the Iran-

Iraq War, beginning in 1980 and ending in 1988. In 1979, just prior to the war, oil

production had reached an all-time high of 3.5 million barrels per day (bpd),

decreased to 2.5 million bpd in 1980, and plummeted to less than 1 million bpd in

1983.

4

Imports during the same time period soared from about $8.5 billion in 1979

to about $17.5 - $21 billion in 1982 and 1983.

5

Some of the increase in that period

may be due to imports of dual-use (items with military and civilian uses)

commodities, but such a marked increase in imports might also have signaled that the

government and Iraqi industries were less able to produce food and goods

domestically in a wartime environment. By 1984, imports decreased dramatically as

the effects of the war caused Iraq’s economy to contract. The cost of living rose

sharply, the dinar was devalued, and the government and other organizations began

to fall behind in payments to foreign contractors.

6

Another period emerged after the end of the war in August 1988, when both

exports and imports increased slightly until international economic sanctions were

imposed directly after Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990. Between 1990 and

1997 international trade virtually collapsed as both exports and imports hovered

between $300-$ 600 million per year.

The third pattern in Iraq’s international trade begins after the implementation

of the Oil-for-Food Program. Between December 1996 and 1998, oil exports were

limited to certain levels, and all exports were closely regulated by the United Nations

until the ending of international sanctions in 2003. Similarly, imports during this

time period were limited to food, humanitarian, and medical necessities. Imports

during this period ranged from $2 to $5 billion and exports from $5 to $14 billion.

CRS-3

7

CRS Report RL30472, Iraq: Oil-For-Food Program, International Sanctions, and Illicit

Trade, by Kenneth Katzman.

8

United Nations, Security Council. Letter Dated 20 May 1996 From the Secretary-General

Addressed to the President of the Security Council. Document No. S/1996/356.

9

United Nations. Report of the Secretary-General pursuant to paragraphs 7 and 8 of

Resolution 1409 (September 2002), Document No. S/2002/1239, November 12, 2002.

10

The thirteen phases were as follows: I, December 10, 1996 to June 7, 1997; II, June 8,

1997 to December 4, 1997; III, December 5, 1997 to May 29, 1998; IV; May 30, 1998 to

November 25, 1998; VI, November 26, 1998 to May 24, 1999, extended until December 11,

1999; VII, December 12, 1999 to June 8, 2000; VIII, June 9, 2000 to December 5, 2000; IX,

December 6, 2000 to June 3, 2001, extended until July 30, 2001; X, July 4, 2001 to

November 30, 2001; XI, December 1, 2001 to May 29, 2002; XII May 30, 2002 to

November 25, 2002, extended until December 4, 2002; and XIII, December 5, 2002 to

program suspension on March 17, 2003.

Sanctions and the Oil-For-Food Program

In August 1990, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 661, imposing

comprehensive economic sanctions following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. From 1991

to 1995, Iraq declined to accept U.N. proposals to allow Iraq to sell limited quantities

of oil to meet the needs of its people because the Hussein regime believed that these

proposals infringed on Iraq’s sovereignty and were limited in scope. The U.N.

Security Council made repeated efforts during the period to alleviate human suffering

in Iraq while pressing Iraq to comply with all relevant U.N. Security Council

resolutions. Without oil export revenues, Iraq could not import sufficient quantities

of food and medical supplies, and living conditions in the country reportedly

deteriorated sharply.

7

On April 19, 1995, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 986, which

proposed that Iraq be permitted to export $2 billion worth of oil every six months so

that the Iraqi government could use the proceeds of the oil sales to purchase food,

medicines, and other humanitarian supplies to meet the needs of its people. Iraq and

the Security Council signed a memorandum of understanding on the implementation

of the Oil-For-Food Program (OFFP) on May 20, 1996 and the first Iraqi oil exports

began on December 10, 1996.

8

The first shipments of food arrived in Iraq in March

1997, followed by imports of medicines in May 1997. From the program’s inception

until its suspension in March 2003, approximately $26.8 billion worth of food,

humanitarian supplies, and equipment was delivered to Iraq under the program.

Nearly 60 percent of the Iraqi population were, to some extent, dependent on monthly

food baskets received under the OFFP.

9

A complete discussion of the Oil-For-Food

Program is found in CRS Report RL30472, Iraq: Oil-For-Food Program,

International Sanctions, and Illicit Trade, by Kenneth Katzman.

The U.N. Security Council continued the Oil-For-Food Program in 180-day

periods known as “phases.” The first phase ran from December 10, 1996 to June 7,

1997. The last pre-war oil exporting period was phase thirteen, which came into

effect on December 5, 2002 and was scheduled to run through June 3, 2003.

10

Iraq’s

exports of crude oil during this period are shown in Figure 3 (p. 9).

CRS-4

11

Sluglett, M. & Sluglett, P. Iraq Since 1958: From Revolution to Dictatorship. New York:

KAI Limited, 1987, p. 35.

12

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) calculations.

On May 22, 2003, the Security Council adopted Resolution 1483, lifting all

economic sanctions on Iraq, with the exception of arms and related military supplies.

The resolution provided for the termination of the OFFP within six months, and the

transfer of all remaining transactions under the program to the Coalition Provisional

Authority (CPA, referred to in the resolution as “the Authority”). In keeping with

Resolution 1483, the OFFP terminated its operations on November 21, 2003.

Iraq’s Exports

Iraq entered the global trade marketplace in the mid-1800s as an exporter of

grains and cereals. As early as the 1930s, however, crude oil became its major export,

and exports of crude accounted for 49.3% of national income by 1953.

11

In the

1980s, crude oil represented 83% annually of all Iraqi exports.

12

Non-petroleum

export products in the 1980s included portland cement, fruit (mainly dates),

fertilizers, and reaction engines. Table 1 illustrates Iraq’s top export products in

1989, the year before the initiation of economic sanctions.

Table 1. Iraq’s Top 10 Exports, 1989

SITC Rev 3 Commodity Million $

3330-Crude oil $11,545.4

3344-Fuel oils, nes $211.3

3343-Gas oils $119.8

3341 — Gasoline and other light oils $78.8

2741- Sulfur of all kinds $39.2

6612-Portland cement $35.7

0579-Fruit, fresh or dried, nes $30.8

5629-Fertilizers, nes $29.6

7144-Reaction engines $29.2

5222-Chemical elements, nes $27.7

Source: United Nations Trade Data

nes=not elsewhere specified.

When economic sanctions were imposed in August 1990, Iraq’s oil sales

dropped from $10.2 billion in 1990 to $305 million in 1991. From 1992 to 1995, oil

exports averaged between $500 and $600 million. Figure 1 illustrates the dollar

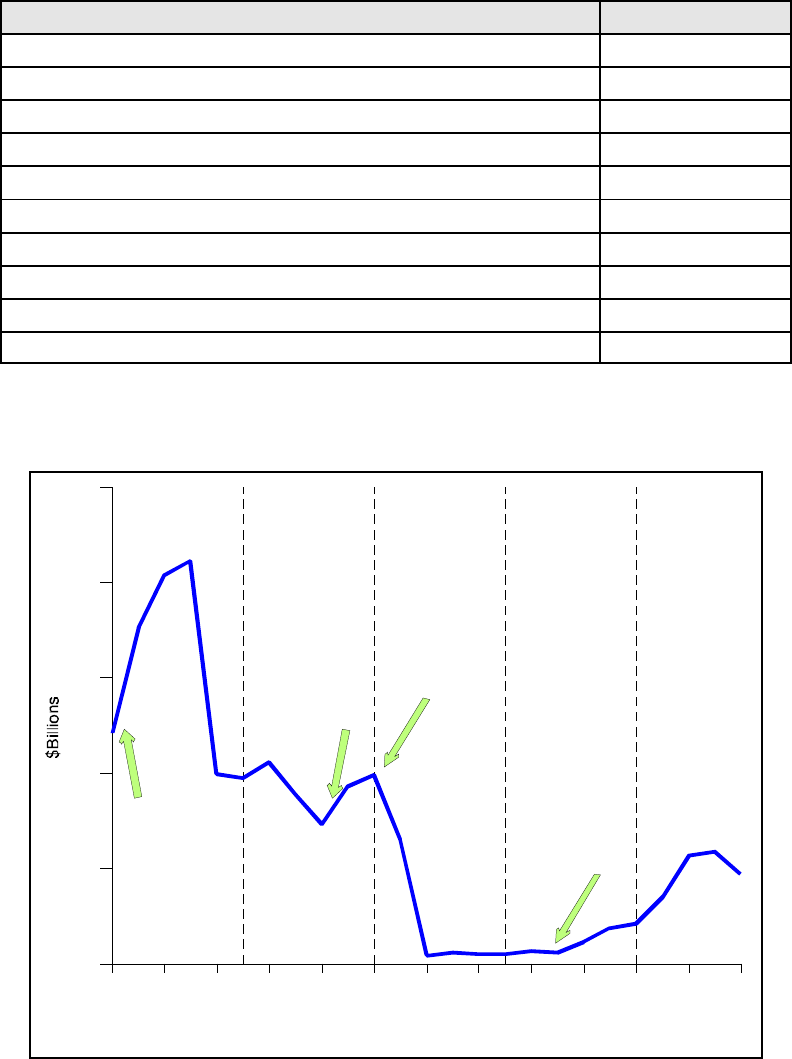

value of Iraq’s exports of crude oil from 1980 to 2003 as reflected in U.N. trade data.

In the year 2000, the highest level of exports achieved during the OFFP, the sharp

CRS-5

13

Department of Energy, Iraq Energy Chronology, 1980-February 2004,Energy Information

Administration, [http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/iraqchron.html].

14

CRS Report RL30472, Iraq: Oil-For-Food Program, International Sanctions, and Illicit

Trade, by Kenneth Katzman.

1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002

$0

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

$30

Invasion of Kuwait;

International

Sanctions Imposed

U.N. OFFP

Implemented

Iran-Iraq War

Begins

Iran-Iraq War Ends

Source: U.N. trade data

Figure 1. Iraq’s Oil Exports, 1980 to 2003

rise in export value can also be attributed to a spike in oil prices between

December1999 and September 2000.

13

A closer look at Iraq’s exports between

December 1996 and March 2003 (see Figure 2) shows that despite periodic increases

in the oil export ceiling and the eventual rescission of the export ceiling in December

1999, Iraq’s oil exports often ran significantly below the permitted level of exports.

This was due, in part, to frequent disputes between Iraqi and U.N. officials over U.N.

efforts to end illicit surcharges placed on oil exports. In addition, Iraq sometimes

unilaterally interrupted the sale of oil to protest Security Council policy or to

challenge the United States and its allies. For example, Iraq suspended its oil sales

for the month of April 2002 in protest of Israel’s military incursion in the West

Bank.

14

Figure 2 illustrates Iraq’s semiannual oil exports under the OFFP

(December 1996-March 2003) by dollar value and by volume.

CRS-6

15

U.S. Department of Energy, Iraq Country Analysis Brief, Energy Information

Administration (EIA), p. 1. [http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/cabs/iraq.html].

16

United Nations, Security Council, Letter dated 6 June 2001 from the Secretary-General

addressed to the President of the Security Council, S/2001/566.

U.N. Phase Number

I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII

0

2

4

6

8

10

0

100

200

300

400

500

Value (Y1) Volume (right scale) (Y2)

Source: U.N. Office of the Iraq Programme

(180-day phases from Dec. 1996 - Mar. 2003)

$2 bill. Export Ceiling

$5.2 bill. Export Ceiling

Export Ceiling Lifted

Figure 2. Iraq’s Exports of Crude Oil, 1996 to 2003

Iraq’s Oil Resources

Since Iraq’s chief export product is crude oil, the country’s economic future, at

least in the short term, depends primarily on its ability to tap into its vast oil

resources. According to U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) analysts, Iraq has 112

billion barrels of proven oil reserves — second only to Saudi Arabia’s 260 billion

barrels of proven reserves — and possible reserves of as much as 220 billion barrels.

Due to years of war, economic sanctions, and mismanagement during the Hussein

regime, Iraq’s oil potential has been largely unexplored. Only 17 of 80 discovered

oilfields have been developed, and few deep wells have been drilled compared to its

neighbors. DOE analysts estimate that only 2,300 oil wells have actually been

drilled, and, of these, only 1,600 are currently producing oil.

15

Iraq’s all-time peak oil production was 3.5 million barrels per day in 1979, just

prior to the war with Iran. Output dropped sharply as the war began, but gradually

recovered to a similar level by 1989-1990. As a result of severe damage to the oil

industry infrastructure during the Gulf War, followed by economic sanctions, crude

oil production was reduced sharply to about 300,000 bpd.

16

From 1990 to the end of

1996, U.N. sanctions prohibited exports of oil, and oil production was limited to the

CRS-7

17

CRS Report RL31944, Iraq’s Economy, Past, Present, and Future, Jonathan E. Sanford,

Coordinator.

18

United Nations. Report of the Group of United Nations Experts Established Pursuant to

Paragraph 30 of the Security Council Resolution 1284 (2000), March 2000, p. 12.

19

U.S. Department of Energy, Iraq Country Analysis Brief, p. 4.

20

Energy Intelligence Group, “Iraq is Primed for Big Oil Opening,” Petroleum Intelligence

Weekly, March 12, 2003

21

United Nations. Report of the Group of United Nations Experts Established Pursuant to

Paragraph 30 of the Security Council Resolution 1284 (2000), March 2000, p. 12.

amount needed to meet internal demand, plus small amounts that may have been

illegally exported.

17

Condition of Infrastructure. Prior to the institution of the Oil-for-Food

Program, the oil infrastructure was partially repaired, but often by cannibalization

and short-term substitution of parts and without access to external equipment or

technology. The Security Council, after determining that the state of Iraq’s oil sector

was “lamentable,” allowed a limited amount of investment in equipment and spare

parts for basic maintenance of the oil infrastructure (a total of $3 billion from June

1998 to June 2001). However, according to the calculations of U.N. oil industry

experts, investment in Iraq’s oil sector from 1990 on was about $0.60 per barrel, in

contrast to the worldwide average of $1.50 per barrel. U.N. experts forecasted

declines in oil production from 5% to 15% per year if the oil infrastructure was not

improved.

18

The position of the United States and its allies during the sanctions

regime, however, was that OFFP funds should be used only for short-term

improvements, and not to make long-term repairs.

19

Oil industry experts assessed Iraq’s pre-war sustainable production capacity at

no higher than 2.8-2.9 million bpd. Conservative estimates for restoring the oil

sector to pre-1990 levels by 2006 range between $5.0-$6.0 billion. Prior to the 2003

war, the regime of Saddam Hussein had a blueprint in place for doubling capacity to

6 million bpd, with foreign oil companies playing a key role.

20

In order to reach this

potential, however, the regime acknowledged that Iraq’s oil sector would require

investment at all levels, including technical services, capital equipment, and

infrastructure.

21

Iraqi authorities estimated that the 6 million bpd target would

require an additional investment of at least $21 billion and would probably take 8 to

10 years to achieve after the lifting of international economic sanctions. Plans to

reach the target included further development of producing oilfields as well as

finding and developing additional fields in the Western Desert.

Post-War Situation

Even though Iraq’s oilfields were captured largely intact, the oil industry has

been hampered by post-war chaos and looting of its oil facilities. Damage and

continued sabotage to infrastructure, refineries, and mainline transport facilities have

slowed efforts to return exports to pre-war levels. Other difficulties in the oil supply

infrastructure, including electrical power and water supply, have further hindered

CRS-8

22

CRS Report RS21626, p. 2.

23

Watkins, E. “U.S. to Deploy Airborne Snipers to Protect Iraqi Pipelines,” Oil and Gas

Journal, October 13, 2003.

24

CRS Report RS21626, Iraq Oil: Reserves, Production, and Potential Revenues, by

Lawrence Kumins. “Sabotage Cuts Flow of Iraqi Crude to Ceyhan; Pipeline in Northern

Network Hit,” Platt’s Oilgram News, August 4, 2004.

25

The Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund was established by the FY2003 Emergency

Supplemental (P.L. 108-11). $2.5 billion was appropriated in this law for reconstruction

efforts.

26

“U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Awards Contracts for Repair of Iraq’s Oil Infrastructure,”

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, News Release No. PA-04-03, January 16, 2004.

27

“Iraq Postpones Negotiating Upstream Deals; Repairs are Priority,” Oil Daily, July 16,

2004.

production.

22

Many observers believe that U.S. and Iraqi protection of oil pipelines

has been improving, and U.S. military commanders recently announced increased

surveillance measures including the deployment of airborne snipers to prevent future

acts of sabotage.

23

Nevertheless, attacks by insurgents on oil pipelines continue,

which has resulted in Iraq’s inability to sustain its prewar production and export

capacity on a regular basis (see Figure 3 on page 9).

Much of Iraq’s current oil production is also needed to meet domestic

consumption requirements, which averaged about 500,000 bpd pre-war, although

current requirements may be at least 100,000 bpd less. Iraqi refineries’ inability to

produce a sufficient supply of needed fuels to meet domestic demand led the CPA

to sponsor imports of gasoline and propane from other countries using U.S. funds.

These imports have continued beyond the transition of power and are paid through

the Development Fund for Iraq, now administered by the transitional Iraqi

government. Iraq is currently importing fuel from Syria, Kuwait, Jordan, Saudi

Arabia, and Iran at a cost of approximately $200 million per month.

24

Initial U.S. post-war reconstruction contracts in Iraq included two contracts for

oilfield repairs funded through the Iraq Relief and Reconstruction Fund.

25

The U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers awarded one contract for work on fields in the southern

area of Iraq to Kellogg, Brown, and Root (minimum value $500,000 - maximum

value $1.2 billion for the life of the contract), and one contract to Parsons Iraqi Joint

Venture (minimum value $500,000 - maximum value $800 million). These contracts

were issued to cover the cost of a range of services including extinguishing oil fires,

environmental assessments and cleanup of oil sites, oil infrastructure condition

assessments, engineering design and construction, oilfield pipeline and refinery

maintenance, procurement and importation of fuel products, distribution of fuel

products within Iraq, and technical assistance.

26

Within the next six months, the

Iraqi transitional government also plans to spend an additional $500 million to

supply its refineries with equipment, spare parts, and chemicals, and about $900

million on projects including oil wells and pipelines.

27

According to DOE statistics, Iraq crude oil production averaged 1.33 million

bpd in 2003, down from 2.04 million bpd in 2002, and 2.45 million bpd in 2001.

CRS-9

28

Wall Street Journal, “Iraq’s Oil Industry is Slowly Rebounding,” November 6, 2003.

29

“Iraqi Oil Exports Stabilized at 1.7 Million b/d,” Oil Daily, July 22, 2004.

30

Cooper, P.J. “Oil and Gas Briefs,” Financial Times, October 30, 2003.

Source: Brookings Institution Iraq Index

May 03

June 03

July 03

Aug. 03

Sept. 03

Oct. 03

Nov. 03

Dec. 03

Jan. 04

Feb. 04

March 04

April 04

May 04

June 04

July 04

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Production Exports

Figure 3. Iraq: Monthly Oil Production and Exports,

May 2003-July 2004

According to OPEC statistics, Iraq’s production averaged 1.7 million bpd in June

2004, 1.9 million bpd in May, 2.38 million bpd in April, and 2.34 million bpd in

March. However, as much as 300,000 bpd of that production has reportedly been

reinjected into oil wells, due to lack of transportation routes from the northern fields

and because oil refineries in the region are not operating at capacity.

28

Nevertheless,

current crude loadings at Iraq’s Basra terminal stood at 1.6 million bpd in July

2004.

29

Iraq’s northern export pipeline remains inoperable due to repeated

sabotage.

30

Iraq’s Imports

Prior to the implementation of economic sanctions, Iraq’s primary imports

included food, motor vehicles, spare parts, iron and steel, and medicines. Table 2

provides Iraq’s top ten imports from the world in 1989, the year prior to the

implementation of international sanctions.

CRS-10

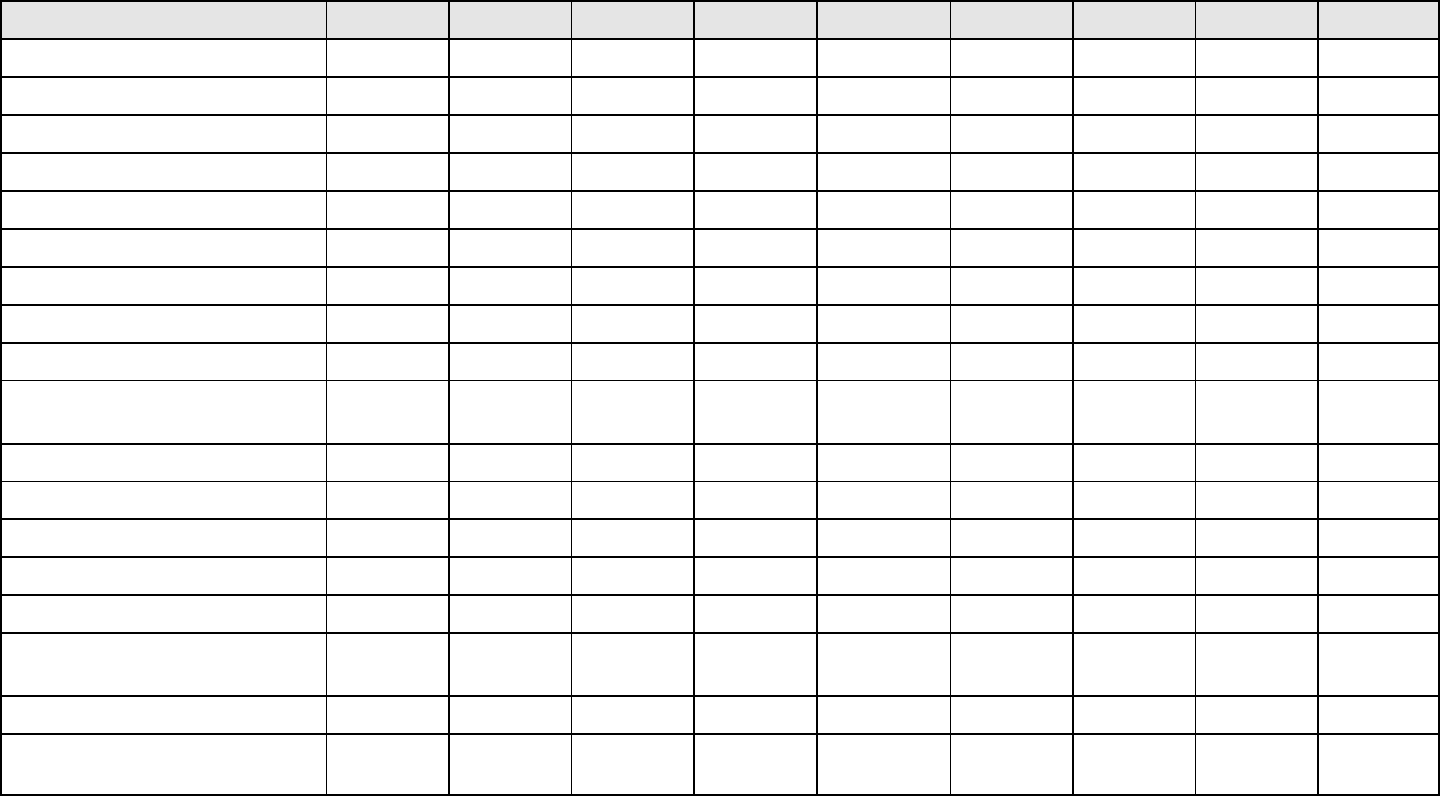

1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002

$0

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

Invasion of Kuwait;

International

Sanctions Imposed

U.N. OFFP

Implemented

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Data

Iran-Iraq War

Begins

Iran-Iraq War

Ends

Figure 4. Iraq’s Imports, 1980 to 2003

Table 2. Iraq’s Top 10 Imports, 1989

SITC Rev 3 Commodities Mil. $

0412 — Wheat, nes $617.3

7843 — Parts and accessories of tractors and motor vehicles, nes $170.4

6793 — Iron and steel seamed tubes $160.9

0112 — Meat of bovine animals, frozen $144.6

7812 — Motor vehicles, nes $139.6

6791 — Iron and steel tubes and pipes $137.8

0423 — Rice $132.2

6762 — Alloy steel bars, rods, nes $130.7

5429 — Mendicaments, nes $124.5

6911 — Metal structures of iron or steel,nes $105.4

Source: U.N. Trade Data. Nes= not elsewhere specified.

Figure 4 illustrates the flow of Iraq’s imports from 1980-2003. Imports rose

rapidly in 1980, peaked in 1981, and continued at a high level until 1982. Major

import commodities during that period included large imports of commodities

officially reported as trucks, spare parts, and other machinery. These imports may

have been legitimate purchases of transportation vehicles, oil machinery, and spare

parts for upgrading and repairing Iraq’s oil production facilities; however, it is also

CRS-11

possible that some of these purchases were converted to military use during the Iran-

Iraq War, or that Iraq’s trading partners used these trade classification categories to

hide exports of armaments and military hardware to Iraq. Table 3 provides the top

import commodities for the period from 1979 to 1983.

Beginning in 1996, all approved imports to Iraq were monitored by U.N. staff,

who reviewed all contracts and ensured that imported goods were on a list of

commodities drafted by the U.N. Security Council. Besides food and humanitarian

supplies, the OFFP also allowed Iraq to import some transportation and

communications equipment, spare parts for oil rigs and other infrastructure, and

consumer goods. Table 4 shows Iraq’s cumulative imports by sector from 1997 to

2002 under the Oil-For-Food Program.

Table 3. Iraq’s Major Imports, 1979-1983

SITC Rev 1 Commodities

(millions of U.S. $)

1979 1980 1981 1982 1983

TOTAL — Total All

Commodities

8,628.1 12,073.8 17,495.1 17,386.5 8,601.0

7323 — Lorries, trucks 485.1 862.3 1,404.3 921.4 183.6

7184 — Const. ,mining

machinery

392.1 518.5 798.4 577.8 76.2

6911 — Structures & parts of

iron

325.5 333.9 640.2 792.7 275.3

7321 — Pass. motor veh. exc

buses

171.3 255.9 465.8 365.7 182.9

7328 — Motor vehicle parts 179.4 349.4 462.1 403.2 214.3

7221 — Electric power

machinery

147.0 199.6 399.9 411.3 229.0

7192 — Pumps, centrifuges 149.2 209.4 390.8 380.7 213.1

7125 — Tractors, non-road 95.0 141.4 357.2 139.2 29.9

7191 — Heating, cooling

equipment

143.4 237.9 355.8 342.9 132.7

7193 — Mechanical handling

equip.

159.6 212.6 298.3 236.7 80.9

6612 — Cement 23.4 68.9 296.7 178.9 99.8

7324 — Special motor vehicles 128.4 149.1 293.2 369.0 118.5

7249 — Telecommunications

equip.

175.8 236.9 289.9 616.7 456.9

7325 — Tractors for trailers 44.1 144.2 280.9 220.3 44.7

7231 — Insulated wire, cable 90.6 144.6 277.8 296.8 129.9

Source: United Nations Trade Data. Commodities are sorted in descending dollar value for the year

1981 (see italics), when Iraqi imports were at their highest level during the period.

CRS-12

31

Andrews, E. “After Years of Stagnation, Iraqi Industries are Falling to a Wave of

Imports,” New York Times, June 1, 2003. Sabbah-Gargour, R. “Arthur Daleys Flourish in

(continued...)

Table 4. Iraq’s Oil-For-Food Imports by Sector, 1997-2002

Sector

Value of Approved Sales

(U.S. $)

Food 13,505,896,754

Agriculture 3,733,280,193

Oil Spares 3,636,458,484

Electricity 3,538,554,784

Food Handling 3,312,345,268

Health 3,025,602,846

Housing 2,720,773,354

Communication/Transportation 2,016,400,979

Water and Sanitation 2,000,721,136

Education 1,146,527,169

Special Allocation 293,559,164

Industry 35,502,417

Religious Affairs 10,285,323

Justice 4,899,283

Construction 2,219,572

Source: United Nations. Office of the Iraq Program. Data are for the largest of the three accounts

in the Iraq Program.

Post-War Situation

Since the lifting of economic sanctions, Iraq has been flooded with new

products, including television sets from South Korea, refrigerators from Iran and

China, new and used cars from Japan and South Korea, and toasters from Germany.

Satellite telephones and portable kerosene stoves, needed because of the absence of

normal telephones and the current lack of cooking fuel, are so plentiful that prices

have declined. Satellite dishes, banned under the Saddam Hussein regime, are also

for sale. Consumers with money have a range of new choices, and the recent

appreciation of the Iraqi dinar has provided them with additional buying power.

Iraqi companies that have had almost no competition due to U.N. sanctions,

however, have had to face the full force of globalization and international

competition almost overnight. An unexpected appreciation of the dinar that made

foreign imports more attractive exacerbated the competitive challenges Iraq’s

manufacturers and state-run companies are facing. The free-market economy shocks

are of some concern to U.S. and British officials, who want to get people back to

work.

31

Despite these concerns, the private industry sector is reportedly experiencing

CRS-13

31

(...continued)

Duty-Free Zone, London Times, August 16, 2003.

32

Statements of Michael P. Fleischer, Former Director of the Private Sector Development,

Coalition Provisional Authority at Iraq Private Sector Development Briefing, August 4,

2004.

33

U.S. Department of Commerce, Business Guide For Iraq website, revised June 4, 2004,

[http://www.export.gov/iraq/bus_climate/businessguide_current.html#exporting].

34

General Accounting Office. Weapons of Mass Destruction: U.N. Confronts Significant

Challenges in Implementing Sanctions against Iraq, GAO Report Number GAO-02-625.

a vibrant recovery according to U.S. officials. Domestic company registration (the

equivalent of incorporation) has tripled to about 30 per day, and unofficial estimates

indicate that private sector employment is growing to encompass between 25% and

50% of all jobs.

32

Nevertheless, unemployment remains very high, estimated at 20 -

38%.

On September 19, 2003, the CPA established a reconstruction levy

(CPA/ORD/19 September 2003/38) which, as of January 1, 2004, placed a 5% tariff

on all imported goods except food, medicine and medical equipment, clothing,

books, and goods delivered as humanitarian assistance. U.N. entities, the CPA,

Coalition forces, nonprofit organizations, other international organizations, and

foreign governments will be exempt from the levy. All proceeds are to be used to

support Iraqi reconstruction efforts. According to U.S. Department of Commerce

figures, Iraq collected over $2.7 million in reconstruction levy fees between April

15, 2004, and June 4, 2004, implying that over $54 million in non-exempt imports

entered Iraq during the same time period.

33

Iraq’s transitional government has kept

the reconstruction levy in place.

Illicit Trade

In the period during which economic sanctions were imposed, the regime of

Saddam Hussein reportedly conducted illicit oil deals with its neighbors and other

countries in order to generate funds that it could use without restriction. The regime

also allegedly imposed surcharges on oil buyers and solicited kickbacks from

suppliers of humanitarian and other civilian goods. Although there are no

authoritative figures for the value of Iraq’s illicit trade, a study released in May 2002

by the General Accounting Office (GAO) estimated that Iraq earned $6.6 billion in

illicit revenue from oil smuggling between 1997 and March 2001.

34

The GAO reported that Iraq smuggled oil through neighboring states, including

Syria, Turkey, and Jordan, and imported illicit and unapproved commodities through

numerous exit and entry points along its borders. Major illicit trade routes were said

to include an oil pipeline to Syria, truck routes through entry points on the Jordanian

and Turkish borders, and shipping in the Persian Gulf.

Prior to the war, U.S. officials were primarily concerned that Iraq might be using

these illicit revenues to purchase prohibited military and weapons-of-mass-

CRS-14

35

Ibid., p. 6.

36

Katz, L. M., “Iraq, U.S. Lock Horns Again.” United Press International, February 10,

2000.

37

“Iraq Making the Most of Porous Sanctions,” USA Today, November 7, 2002. Rieff, D.

“Were Sanctions Right?” New York Times Magazine, July 27, 2003.

38

“Iraq Postpones Negotiating Upstream Deals; Repairs are Priority,” Oil Daily, July 16,

2004.

39

Eckholm, Erik, “On Iraq’s Border, Sailors of the Desert Smuggle Subsidized Gasoline,”

New York Times, August 21, 2004, page A7.

40

Ibid.

destruction (WMD) technology. The GAO report also found, however, that the

sanctions may have been partially effective in deterring Iraq from obtaining most

conventional weapons.

35

In February 2000, the Clinton Administration accused the Iraqi government of

using financial resources gained from illicit trade to build nine lavish palaces, valued

at about $2 billion.

36

The second Bush administration concluded that international

sanctions were not effective, and accused Iraq of using illicit revenue to finance

active nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons programs.

37

Post-War Situation

Although illicit government fuel smuggling ended after the war, individuals are

now reportedly smuggling large amounts of fuel, apparently stimulated by lower oil

prices in Iraq relative to world market prices. Some smugglers are reportedly drilling

into pipes between the refinery and shipping terminals, according to Iraqi oil

officials.

38

Others are purchasing fuel in Iraq, filling up larger trucks and cars fitted

with extra fuel tanks, and driving across the border to Jordan where the subsidized

fuel can be resold at more than ten times the cost.

39

In addition, some gas station

owners with the rights to shipments of diesel fuel from Iraqi distribution companies

are reported to be paying drivers to divert the shipments of diesel to sell the

shipments to smugglers at a greater profit than can be received at their filling stations.

Coalition forces and the interim Iraqi government have tried to stamp out the fuel

smuggling, however, officials expect the smuggling to continue as long as the fuel

is subsidized at such a cheap rate relative to fuel prices elsewhere.

40

Major Trading Partners

As is the case with most oil-producing countries, many of Iraq’s leading pre-war

export trading partners were industrialized nations. In the post-war environment,

regional trading relationships, especially with Jordan and Morocco, have gained

importance. Certain trading relationships established during the OFFP period, such

as imports from Vietnam, have also increased. In 2003, Iraq’s top ten export trading

partners were the United States, Canada, Jordan, Italy, Morocco, Brazil, Spain, the

Netherlands, Japan, and Australia. In terms of Iraq’s imports, Jordan was its largest

CRS-15

41

United States Congress, House Committee on International Relations. Testimony on

Russia’s Policy toward Iran and Iraq, by C. Wallander of the Center for Strategic and

International Studies (CSIS), Washington, DC, February 25, 2003.

trading partner in 2003, followed by Vietnam, the United States, Germany, Russia,

the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Australia, and Japan. Table 5 shows Iraq’s top

trading partners in terms of imports and exports for 2003. Table 12 in Appendix B

provides trade statistics for Iraq’s major trading partners from 1982-2003.

Table 5. Iraq’s Top 10 Export and Import Trading Partners, 2003

Exports

(millions of U.S. $)

Imports

(millions of U.S. $)

United States $4,466.5 Jordan $693.1

Canada $797.7 Vietnam $537.8

Jordan $769.3 United States $347.2

Italy $724.5 Germany $253.2

Morocco $481.1 Russia $240.2

Brazil $398.4 United Kingdom $237.7

Spain $302.3 France $190.7

Netherlands $269.8 Italy $186.9

Japan $99.5 Australia $178.8

Australia $27.6 Japan $84.1

Source: International Monetary Fund, Direction of Trade Statistics.

Pre-War International Interests

Despite economic sanctions, several countries regarded Iraq as an important

trading partner and expressed concern before the war that their national interests

might be compromised if a newly-established Iraqi government is primarily

sympathetic to U.S. interests. These countries were concerned about lost trade and

possible loss of investment opportunities in Iraq’s oil sector.

Russia. Russia’s cumulative trade turnover with Iraq from 1997-March 2003

amounted to $7.7 billion. Iraq was an important trading partner to Russia because

certain exports were sold to Iraq that were not otherwise competitive in the global

market, including Volga cars, grain harvesters, and power generation equipment.

Russian analysts estimated that the industrial sector may lose as much as $2.5 billion

if contracts signed with the regime of Saddam Hussein fall through.

41

CRS-16

42

Feifer, G. “Russia: Proposed Economic Agreement with Iraq Raising Questions.” Radio

Free Europe/Radio Liberty, August 19, 2002.

43

Business Middle East, Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), January 16, 2003.

44

“Focus: Oilfields Could Slip Out of Russia’s Reach,” Petroleum Economist, February 10,

2003.

45

Bostnavaron, F. “France Remains Iraq’s Leading European Trading Partner.” Le Monde,

September 13, 2002.

46

“Over 90 Companies Going to Baghdad Trade Fair — Iraqi Official,”Agence France

Presse, October 29, 2002.

47

Sluglett, M. & Sluglett, P. Iraq Since 1958: From Revolution to Dictatorship. New York:

KAI Limited, 1987, p. 288.

48

Marcel, Valerie, The Future of Oil in Iraq: Scenarios and Implications, The Royal

Institute of International Affairs, Briefing Paper No. 5, October 2002, p. 7

[http://www.riia.org].

In August 2002, Russia and Iraq signed a five-year “economic cooperation” and

trade agreement valued at $40 billion. The trade package called for cooperation in

several industry sectors, including oil, electricity, and railroads.

42

Russia and Iraq have signed numerous oil and gas agreements since 1997.

Russian firms had not started work on these projects, however, even though U.N.

officials had approved some of the contracts. Iraq’s oil ministry officials expressed

frustration with the inaction and, in January 2003, unilaterally terminated a major

contract with Lukoil, saying that the company had failed to fulfill its obligations

under the contract. The company called Iraq’s move “blackmail” and vowed to

contest the decision in court.

43

In spite of this setback, Russia held more oil contracts

in pre-war Iraq than any of its foreign competitors — a strategic advantage Russia

fears it might lose if Iraq’s government is replaced by a regime with greater

allegiance to the United States.

44

Russian oil companies, especially Lukoil, continue

to have an interest in bidding on oil contracts in Iraq, and are maintaining their

contacts with the Iraqi oil ministry to that end.

France. Iraq was an important market for French goods, especially in the

capital goods, automotive, and food processing sectors. Other pre-war French

exports to Iraq included industrial, telecommunications, and electrical equipment.

The regime of Saddam Hussein considered France such an important trading partner

that in March 2002, the Iraqi embassy in Paris opened a new trade section dedicated

to continued improvement of Iraq’s trade relationship with France.

45

Over 90 French

companies attended Baghdad’s annual trade fair held the following November.

46

French oil companies also maintained cordial relations with Iraq’s oil officials.

47

France’s major oil company, Total S A, (formerly TotalFinaElf), had secured a

memorandum of understanding with Iraqi oil officials during the Saddam Hussein

regime for drilling contracts worth a total of $7.4 billion. A successful outcome

would have doubled the group’s reserves with an added 10 billion barrels, and was

forecasted to increase its daily production by 16%.

48

CRS-17

49

“Oil, Business, and the Future of Iraqi Sanctions.” PolicyWatch No. 283, Washington

Institute for Near East Policy, November 24, 1997.

50

“Another Contract in Place to Continue Construction in Iraq,” Coalition Provisional

Authority News Release, April 2, 2004 [http://www.rebuilding-iraq.net].

51

See CRS Report RL32229, Iraq: Frequently Asked Questions About Contracting, by

Valerie Bailey Grasso.

52

“Iraq Creates Supreme Council to Oversee Oil and Gas Industry,” Oil Daily, July 19,

2004.

53

“Vietnam Resumes Rice Exports to Iraq,” Financial Times Information. Vietnam News

(continued...)

United States. The United States continues to be the leading importer of

Iraq’s oil. Some in the international community believed that U.S. needs for

continuous supplies of oil at lower cost and the involvement of U.S. oil interests in

Iraq played a part in leading the United States to wage war against the Hussein

regime. As early as 1997, nine U.S. oil companies, including Mobil, Conoco,

Chevron, Occidental, Arco, Exxon, Texaco, Coastal, and Amoco, reportedly

contacted Iraq to express interest in developing Iraqi oil fields once sanctions were

lifted.

49

Some international observers were also concerned that the initial Iraq

reconstruction contracts favored U.S. companies. Two American companies,

Kellogg Brown and Root (KBR), and Parsons, were the primary companies initially

selected for key reconstruction projects specifically related to oil development.

50

The

selection of these companies and other U.S. contractors for reconstruction contracts

led to questions concerning the degree to which subsequent contracts would be open

to a competitive bidding process.

51

All of Iraq’s oil assets are now controlled by the interim government. Some

analysts still express concern, however, that an Iraqi government sensitive to U.S.

interests may favor American companies when issuing future contracts for oilfield

development. The government’s creation of a supreme council to establish a

comprehensive oil policy, combined with the desire of the oil ministry to “achieve

the highest revenue possible” may indicate that, to the extent the Iraqi government

focused on long-term contracts at this time, it is intent on keeping its options open

with regard to future contract awards.

52

Table 6 in Appendix B illustrates major U.S. imports from Iraq in 2003 (annual)

and 2004 (year-to-date). Table 7 shows the top U.S. exports to Iraq for the same

time periods.

Asia. Several Asian countries also had significant trade and economic ties to

Iraq, and expressed concern that their economies might suffer due to instability

caused by the war. Prior to the war, Iraq was the largest importer of Vietnamese rice,

at a total of 860,040 tons in 2002. Because these imports were conducted under the

Oil-for-Food Program, Vietnam also received a slightly higher than market-rate price

for the rice. Suspension of the OFFP prior to the war was a concern for Vietnamese

officials until U.N. approval to resume shipments was given in early May 2003.

53

CRS-18

53

(...continued)

Briefs. May 5, 2003.

54

“Taiwan Expresses Interest in Securing Iraq Contracts,” Asia Pulse, April 21, 2003.

55

“Iraq-Thailand Trade Looks Promising if U.N. Ends Sanctions,” Emerging Markets

Datafile, Xinhua News Agency, January 12, 2002.

56

“China Adopts Cautious Approach to Iraqi Oil,” Oil Daily, December 17, 2002.

57

Marcel, Valerie, The Future of Oil in Iraq: Scenarios and Implications, The Royal

Institute of International Affairs, Briefing Paper No. 5, October 2002, p. 7

[http://www.riia.org].

58

“Itochu Signs Iraqi Crude Oil Contract,” Japan Economic Newswire, August 15, 2003.

59

“Iraqi Oil is for Iraqis,” Financial Times, November 28, 2003.

60

Middle East Regional Trade Overview, Economist Intelligence Unit, March 19, 2003.

Taiwan’s trade officials had scheduled an ambitious trade agenda for the Middle

East region and are currently seeking a role for its computer firms in the U.S.-led

reconstruction program in Iraq.

54

Thailand signed a bilateral trade and investment

cooperation agreement with Baghdad in January 2002. Thailand’s pre-war exports

to Iraq included rice and consumer products, and Thai officials expressed a desire for

deeper trade ties once U.N. sanctions were lifted.

55

Asian oil companies have also been involved in contract bids in Iraq. The

China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and China North Industries

Corporation (Norinco) signed a 1997 contract with SOMO involving a $1.3 billion

investment to develop the Ahdab field in southern Iraq to a capacity of 90,000 barrels

per day. Only feasibility studies on the project could be conducted prior to the lifting

of sanctions.

56

India’s ONGC and Indonesia’s Pertamina signed agreements in 2000

for oil development in the Western Desert region, and PetroVietnam signed a

preliminary agreement to develop the Amara field.

57

On August 15, 2003, Japan’s

Itochu Corp. announced that it had signed a contract to import an unspecified amount

of Iraqi crude oil from October to December. Mitsubishi Corp., also from Japan,

signed a contract last month with SOMO for 40,000 bpd from August to December

2003.

58

Pre-War Regional Trade

Jordan. After the imposition economic sanctions by the U.N., Jordan and Iraq

began signing trade protocols on an annual basis, renewed each February. Iraq

provided Jordan with oil at highly subsidized rates, and in exchange, Jordan provided

Iraq with needed goods equal to the agreed value of the oil provided. The value of

the trade agreement varied between $200 and $700 million annually, making Iraq the

single largest market for Jordanian goods. The arrangement was reportedly

terminated by Iraqi authorities in early November 2003.

59

During the period when

sanctions were imposed, the United Nations “took note” of the arrangement, deeming

that it was neither permitted by nor expressly violated U.N. sanctions.

60

CRS-19

61

“Trade in Turkey: Bridging Maneuvers,” EIU Business Middle East, Economist

Intelligence Unit May 1, 2002.

62

EIU Business Middle East, Economist Intelligence Unit, February 16, 2000.

63

EIU Business Middle East, Economist Intelligence Unit April 1, 2001.

64

Van Schaik, J. “Syria At Last Admits to Iraqi Oil Imports,” Oil Daily, April 9, 2003.

Turkey. Prior to the implementation of sanctions, Turkey was one of Iraq’s

major trading partners, with total trade between the two countries valued at about $3

billion per year. There was also a brisk transit business, from which Turkey received

approximately $1 billion per year by trucking goods to Iraq from Turkish ports.

Estimates of Turkey’s cumulative losses from the economic sanctions range from $20

to $60 billion. However, sanctions have not been a total loss for Turkey, as Turkish

firms reportedly won export contracts under the OFFP valued at $340 million in

2002, making Turkey Iraq’s seventh-largest supplier under the U.N. program.

61

Illicit trade in diesel fuel reportedly flourished along the Turkish border with

Iraq during the implementation of sanctions, involving as many as 500 trucks per day

at its peak. The smuggling was done using specially modified trucks that would carry

food from Turkey into Iraq, and would pick up deeply discounted fuel products for

the return trip. Turkish authorities made intermittent attempts to crack down on the

illegal smuggling, mainly at times when the black market threatened its own

economic or security interests. However, because the oil sales also provided revenue

to Turkey’s impoverished southeastern region, Turkish officials sometimes ignored

the illegal trade.

62

Syria. From November 2000 to April 2003, Iraq illicitly exported oil to Syria

via a 50 year-old pipeline that had been previously unused for almost 20 years.

63

The

Iraqi flow of oil, purchased at discounts of up to 50% of market value, was a

moneymaker for the Syrian economy. Syria used the illegal Iraqi crude to meet up

to one-half of its own domestic oil needs, and sold more of its own crude oil at

market prices. Iraq exported an estimated 200,000-250,000 barrels per day through

the pipeline and earned about $800 million through the trading arrangement. On

April 8, 2003, Syrian oil officials indirectly confirmed the illicit trade agreement

when the Syrian state oil company, Sytrol, told its clients that, effective immediately,

export volumes for full-year 2003 would be cut by 40%, meaning that exports for the

remaining nine months of the year would be cut by more than half.

64

This signaled

that Iraqi oil probably accounted for that share of Syria’s pre-2003 export volume.

Other Regional Trade. Iraq also entered into trade agreements with other

countries in the region, including a 1997 “Arab Free Trade Area Agreement” signed

with thirteen other Arab countries, including Egypt, Jordan, Syria, United Arab

Emirates, Bahrain, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, and

Morocco. The countries agreed to reduce tariffs on goods traded among them by

10% per year, fully eliminating tariffs within ten years. Several of these countries,

including Iraq, subsequently signed bilateral or multilateral agreements with each

other accelerating tariff reductions, or even moving directly to free trade.

CRS-20

65

Embassy of Egypt. Memo to the U.S. State Department, Commercial and Economic

Office, Washington, DC, January 31, 2001.

66

“Iraq: Squaring Up to Old Challenges,” Petroleum Economist, August 6, 2004.

67

“BP Sees No Rush to Join Iraqi Upstream,” Platt’s Oilgram News, June 28, 2004.

68

“BP and Shell Signal First Interest in Iraqi Oil Fields,” The Business, August 22, 2004.

69

“Lukoil Launches Iraqi Training Program, with Eye on West Qurna,” International Oil

Daily, July 28, 2004.

In January 2001, Iraq entered into free trade agreements with Egypt, Syria, and

Tunisia under the 1997 agreement. Egypt, in particular, sought to reassure the United

States that the agreement would not affect the nature of Egypt-Iraq trade, and that

the agreement was consistent with guidelines put forth in the OFFP.

65

Table 13 in Appendix B shows trade statistics for Iraq’s trade with regional

trading partners from 1982 - 2003.

Post-War Trade and Investment Prospects

The current security situation, combined with uncertainties surrounding Iraq’s

stability following the transfer of power to a transitional government, has reportedly

cooled the interest of some major foreign oil companies to tap Iraq’s undeveloped oil

reserves, at least in the short term. According to John Browne, BP’s chief executive,

“Iraq is not on anyone’s radar screens right now.”

66

Although Browne said that BP

would “obviously” be interested in working in Iraq’s upstream eventually, he said

“our own view is that you really do have to have to see a government in power for

some time, who has made up their mind about what they want a state oil company to

do and what, if any, role the foreign oil companies should take.”

67

Despite the CEO’s comments, BP reportedly joined with other major European

oil firms (Royal Dutch/Shell, Eni, and Repsol) and several smaller firms in placing

bids for a small-scale ($10 million) Iraqi government contract to study oil reserves

in the Kirkuk and Rumaila fields and develop a detailed plan on how to best exploit

them. A contract of this size would not normally be attractive to these oil majors, but

in this case, it may be viewed as a way to examine Iraq’s oilfield data and establish

a rapport with members of the country’s oil ministry while incurring minimal risk.

68

The move also suggests that some of the major firms are positioning themselves to

reenter Iraq once a permanent government is established and internal security issues

are resolved.

Some oil companies are also helping with the training of Iraqi oil specialists,

especially Russia’s Lukoil, which hopes to keep its prospects of production-sharing

contracts with the Iraqi oil ministry alive. Although Iraq’s Foreign Minister Hoshyar

Zebari says that the government is keeping Iraq’s options open relative to any

existing or future Lukoil agreements, he has reportedly acknowledged that Russia has

legitimate interests in Iraq, is interested in participating in the country’s rebuilding,

and has good chances for future consideration.

69

CRS-21

70

“Norway’s DNO Signs Pact with Kurds to Explore in Northern Iraq,”International Oil

Daily, June 30, 2004.

71

Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, July 26, 2004.

72

Ibid.

73

“Iraq Postpones Negotiating Upstream Deals; Repairs are Priority,” Oil Daily, July 16,

2004.

74

Ibid., p. 367.

A Norwegian independent oil company, DNO, announced on June 28, 2004 that

it had entered into an agreement with the Kurdistan regional government to explore

for and develop oil and gas in Iraq’s northern region. DNO said that it would be the

operator and sole contractor for the area covered by the agreement. This deal is

controversial because (1) many are skeptical that the Kurds have a strong enough

claim to the region to strike a firm deal, (2) it raises broader issues of Kurdish

nationalism, and (3) it directly challenges the rights of the transitional government

in Baghdad to oversee foreign investment in Iraq.

70

In response to the agreement,

Iraqi interim Prime Minister Iyad Allawi warned that “companies that wish to be

welcomed here in the future should not enter into or try to pursue the implementation

of agreements with persons who are not empowered to represent the sovereign

government of Iraq.”

71

Following the transition of power from the CPA to the interim government in

June 2004, Iraq’s interim government established a Supreme Oil and Gas Council,

headed by Allawi, to draw up comprehensive policies for Iraq’s oil sector. The new

council is made up also of the deputy prime minister, the ministers of oil, finance,

planning and international cooperation, a minister of state, a central bank governor,

and an advisor. The council’s role is to approve medium and long term plans, and

major investments and their financing. In the longer term, its role is to approve

contracts with foreign investors, define an oil marketing policy, determine domestic

pricing for petroleum products, and distribution of the proceeds.

72

Although the

interim government has issued several tenders for repairing its oil infrastructure, it

has decided to postpone negotiating long-term upstream foreign investment deals,

even if the security situation improves. At the moment, its priority is to focus on

raising refinery output so that Iraq can stop importing refined products (especially

gasoline) and rehabilitate existing oil fields.

73

U.S. Economic and Trade Policy

Many in Congress and the Bush Administration believe that one of the

hallmarks of success in post-Saddam Iraq will be the rejuvenation and redevelopment

of Iraq’s economy. In addition, the 9/11 Commission recommended that U.S. efforts

to counter terrorism “should include economic policies that encourage development.”

The Commission mentioned Iraq as a specific example, saying that if “Iraq becomes

a failed state, it will go to the top of the list of places that are breeding grounds for

terrorism at home.”

74

Many agree that rebuilding Iraq’s economy is a compelling

U.S. national interest.

CRS-22

75

“Iraq: Risk Ratings: Economic Forecast Summary” EIU Country Risk Service, Economist

Intelligence Unit, August 1, 2004. EIU bases these figures on a 55% chance that a stable,

sovereign government will be achieved which will, in turn, alleviate some security concerns.

76

Abolfathi, Farid, “Iraq: Current Situation,” Global Insight, August 25, 2004.

77

Web Page of the Iraq Project and Contracting Office, [http://www.rebuilding-iraq.net].

78

Abolfathi, Farid, “Iraq: Current Situation, Global Insight, August 25, 2004.

At this time, the most significant threats to economic redevelopment are

concerns about the internal security environment due to ongoing insurgency and the

viability of Iraq’s interim government and the continuing progress of its transition to

democracy. Some observers are also concerned that a future permanent government

of Iraq may repeal some of the CPA-established laws that favor business

development in Iraq, such as those allowing foreign investment and repatriation of

capital.

The Bush Administration has begun the process of normalizing trade relations

with Iraq and on September 7, 2004, designated Iraq as a beneficiary developing

country under the Generalized System of Preferences.

Current State of Iraq’s Economy

Although many larger U.S. and multinational businesses not working in Iraq on

U.S. government reconstruction contracts are taking a “wait and see” approach

toward investing in the country, the Iraqi economy is reportedly growing at a rapid

pace despite persistent security and stability concerns. The Economist Intelligence

Unit (EIU) estimated that Iraq’s real gross domestic product (GDP) contracted by

21.8% in 2003 due to the war, but forecasts GDP growth of 40.3% in 2004 and

25.0% in 2005.

75

Much of the economic growth is reportedly due to the U.S.-

appropriated funds allocated to reconstruction of Iraq’s infrastructure being pumped

into the economy.

76

The Iraq Project and Contracting Office (PCO, formerly the

Program Management Office under the Coalition Provisional Authority) estimates

that between 250 and 300 Iraqi firms are working on reconstruction contracts and that

87,500 Iraqi employees are affiliated with the PCO.

77

Consumer spending on

imported goods is also boosting economic activity as these goods have become more

available and more affordable since the end of economic sanctions. There has also

reportedly been a boom in real estate.

78

The Bush Administration is currently attempting to attract smaller and medium-

sized U.S. businesses to invest in Iraq despite security and stability concerns.

Although most major business opportunities still involve work on U.S.-funded

reconstruction contracts, efforts are also being made to facilitate U.S. business

contacts with Iraqi government ministries and to assist businesses in exploring

private sector investment and export possibilities.

At a recent event sponsored by the Iraq Investment and Reconstruction Task

Force, Michael P. Fleischer, the former director of private sector development for the

CRS-23

79

Statistics were based on polling and other collection methods by the Iraq Reconstruction

Task Force and not officially released by Iraq’s interim government.

80

Iraq Update, Economist Intelligence Unit, September 2004.

81

Department of Commerce. Iraq Investment and Reconstruction Task Force. Iraqi Private

Sector Development Briefing, August 4, 2004. A webcast of the briefing is available at

[http://www.export.gov/iraq/other/iraqreconstruction080404.wmv].

82

For a comprehensive discussion of security issues in Iraq, see CRS Report RL31339, Iraq:

U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance, by Ken Katzman.

Coalition Provisional Authority provided some basic (unofficial) statistics

79

illustrating the improvements Iraq’s domestic business sector has made since the end

of the war, including the following:

! Unemployment appears to be decreasing. Through polling

conducted in February 2004, Iraq’s unemployment rate was

estimated at 28%. U.S. officials indicated more recent polling

indicates a reduction in unemployment to 20%. The Iraqi

government in late July 2004 estimated the unemployment rate at

38%, however.

80

Although the methodology behind any of these

calculations is unclear, most observers believe the latter figure to be

more realistic.

! The composition of employment is shifting. Recent estimates

indicate that the private sector may employ as much as 50% of the

work force.

! The private sector in Iraq is making significant progress. Since

April 2003, over 5,000 new Iraqi companies have been established.

Businesses are registering (the equivalent of incorporation) at a rate

of almost 30 per day.

! Private sector business development is being funded not only by

resident business capital, but through repatriation of funds from

Iraqis living overseas. Informal estimates indicate that as much as

$2 million per day may be flowing into Iraq to purchase real estate

and fund businesses.

! Deposits held by Iraq’s 19 private sector banks increased by 60%

between September 2003 and February 2004, and lending increased

by 23% in the same time period.

81

Most observers believe these statistics are quite optimistic. The transitional

Iraqi government and U.S. forces continue to face significant security challenges

from the militia of Shia cleric Moqtada al-Sadr and from Sunni insurgents, possibly

aided by elements of al Qaeda.

82

Persistent violence, combined with repeated

kidnappings of foreign contractors and journalists, seems to be keeping a great deal

CRS-24

83

Pickering, Thomas R. and Schlesinger, James R., co-chairs, Iraq: One Year After,

Council on Foreign Relations, March 2004, p. 24.

84

“Election Wobble,” EIU Viewswire, September 15, 2004.

85

“Export-Import Bank Support for U.S. Exports to Iraq,” Export-Import Bank Fact Sheet,

December 2003.

86

U.S. Department of Commerce. “Doing Business in Iraq,” Iraq Investment and

Reconstruction Task Force web page, [http://www.export.gov/iraq/bus_climate/faq.html].

87

Department of Commerce. Iraq Investment and Reconstruction Task Force. Iraqi Private

Sector Development Briefing, August 4, 2004.

of foreign investment away from Iraq. Most analysts believe that improvements in

security are critical to Iraq’s sustained economic growth.

83

Some analysts believe that the continuing security threat may delay elections of

a transitional government scheduled for January 2005 despite any declarations of

interim government leaders to the contrary.

84

Any postponement in the establishment

of an elected sovereign government in Iraq may also delay the infusion of long-term

foreign investment that most observers believe is necessary for full development of

Iraq’s economy.

Exim Bank and OPIC Facilitation. Although the Export-Import Bank

(Exim Bank) of the United States is not currently providing companies interested in

investing in Iraq with its usual trade financing products, the bank’s directors

approved a $500 million short-term insurance facility to support transactions through

a newly-established Trade Bank of Iraq (TBI). The Exim Bank insures letters of

credit issued by TBI and confirmed by a commercial bank against the failure of TBI

to pay the confirming bank under an irrevocable letter of credit. The Exim Bank

further provides comprehensive coverage on short term credits extended to TBI by

an insured bank. U.S. exporters will receive payment under letters of credit issued

by the insured bank. The Exim Bank will also consider applications under all of its

products (e.g., working capital guarantee, loan guarantee, export credit insurance, and

direct loans) to support the sale of goods and services to Iraq, provided there is a

creditworthy source in a third country in the Middle East or elsewhere willing to

provide security for the loans.

85

Political risk insurance is being made available through the Overseas Private

Investment Corporation (OPIC) to cover currency inconvertability, expropriation, and

political violence. Coverage is also offered that is more appropriate to contractors,

exporters, and those providing technical assistance and management services. Stand-

alone terrorism coverage is also being provided.

86

As of July 2004, OPIC has written

$29 million worth of investment insurance for Iraqi projects, and another $100

million is in the pipeline.

87

Normalizing Trade Relations

The Bush Administration, as authorized by Congress, has lifted most U.S.

sanctions on Iraq, beginning with Presidential Determination 2003-18 of March 24,

CRS-25

88

Presidential Determination No. 2003-18 of March 24, 2003 (68 F.R. 16165), as authorized

by sec. 507 of P.L. 108-7, the Foreign Operations, Export Financing, and Related Programs

Appropriations Act, 2003.

89

Presidential Determination No. 2003-23 (68 F.R. 26459), May 7, 2003.

90

Executive Order 12722 of August 2, 1990, “Blocking Government Property and

Prohibiting Transactions with Iraq,” 55 F.R. 31803.

91

Executive Order No. 13350 (69 F.R. 46055), July 29, 2004. The executive order revoked

Executive Order 12722 of August 2, 1990, and modified Executive Orders 13290, 13303,

and 13315.

92

Executive Order No. 13303 (68 F.R. 31931), May 22, 2003.

93

Executive Order No. 13315 (68 F.R. 52315), August 18, 2003.

2003, in which the President determined that “the provision of assistance or other

financing for Iraq important to the national security interests of the United States.”

88

On May 7, 2003, the President suspended the Iraq Sanctions Act of 1990 (P.L.

101-513, implemented U.S. trade embargo and U.S. compliance of U.N. economic

sanctions against Iraq), as authorized by sec.1503 of the Emergency Wartime

Supplemental Act, 2003 (P.L. 108-11).

89

On July 29, 2004, in Executive Order 13350, the President terminated the

emergency with respect to Iraq previously declared in Executive Order 12722,

90

determining that the situation that gave rise to the declaration of a national

emergency under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (50 U.S.C.

1701 et seq) and the National Emergencies Act (50 U.S.C. 1501 et seq) has been

significantly altered by the removal of the regime of Saddam Hussein.

91

The

termination of the national emergency formally ended the economic sanctions

imposed by the United States on Iraq following the 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

A national emergency still exists with respect to protecting the Development

Fund for Iraq (DFI) and Iraq’s petroleum assets, and blocking property of the former

regime. Executive Order 13303 (May 22, 2003) protects the Development Fund for

Iraq (DFI), Iraqi petroleum and petroleum products from”the threat of attachment or

other judicial process.”

92

The President found that such judicial processes would

constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign

policy of the United States.

Executive Order 13315 of August 18, 2003, blocking the property of the former

regime and certain senior officials under the same presidential authority, is also still

in effect. The executive order also authorizes the confiscation and repatriation of

additional property of the former regime, or the property immediate family members

of officials, and controlled entities, and designates that these properties be transferred

to the Development Fund for Iraq.

93