Indus Water Treaty Between Pakistan and India of 1960:

An analysis of its journey over six decades and the scope for improvements

Husnain Afzal

Indus Water Treaty Between Pakistan and India of 1960: An analysis of its journey

over Six decades and the scope for improvements.

1.0 Case Description

Geolocation:

34.939423, 72.871971

Population

270 million

Length of Indus River

3200 km

Total Drainage Area

1,165,000 square km

Most-notable

tributaries

The Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, Sutlej and Kabul

Climate Descriptors:

Mostly Semi-Arid, the annual precipitation in the Indus region

varies between 125 and 510 mm

Usage of Indus waters:

90% of the available water in canals is used for agriculture

Other important Uses

of Water:

Hydropower, water supply and Industrial usage

Riparian’s:

Pakistan, India

Agreements:

Indus Water Treaty, 1960

Dispute resolution and

negotiations

Indus water commission of Pakistan and India

1.2 Case Summary

The undivided India had 20 river basins of which Pakistan shared only the Indus basin with India.

The economy and population of Pakistan rely heavily on Indus water with 21% of GDP, 45% of

employment and 60% of exports are dependent on the Indus. Dispute arose between the countries

soon after partition in 1948, with India asserting its hegemony and sovereignty over waters while

Pakistan vying for continuity of water flow to protect its existing and future water uses. This

situation was coupled with territorial control over disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir. In

1951 World Bank intervened and after almost a decade long process of negotiations the Indus

Water Treaty was signed by the two countries in 1960. The treaty gave exclusive rights on the flow

of three western rivers of the Indus basin; the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab to Pakistan, whereas the

flow of three eastern rivers: the Ravi, Beas and Sutlej were reserved for India.

The treaty was entirely focused on the management of surface water, criteria were laid on

construction of infrastructure such as dams and barrages and the rights and obligations of the two

parties regarding surface waters of the Indus river system only. Consequently, it resulted in a zero-

sum approach. The riparian’s are only concerned about relishing their part of the cake and are not

bothered about the consequences for the other people who had been connected with the River. The

diversions of water on the eastern rivers have resulted in ecological disaster in the downstream

reaches of the Sutlej, Beas and Ravi in Pakistan. Many stretches have been converted into sand

dunes or silt hills, water quality has deteriorated, groundwater tables have sunk, and flora and

fauna has been destroyed. This is because the treaty did not deal with subjects such as ground

water, water quality, climate change, ecological aspects, other players connected with the basin

2

and population growth with the passage of time. Hence the treaty was for division of waters and

not sharing of potential benefits of Indus system of rivers.

Growing population, climate change, urbanization and add industrialization is bound to impact the

livelihood of the people whose lives are connected with waters of the Indus Basin. It is in collective

interest of the parties to jointly monitor climate change its effects on Indus Basin and device

mitigation measures. The key to building mutual trust lies in the transparent and efficient exchange

of data. The governments may agree to appoint independent consultants to evolve a standard

operating procedure for data sharing and agree to install telemetry systems so that the issue can be

resolved once for all.

The treaty has provisions to cater for unaddressed issues. Under Final Provisions, article XII,

Clause 3 of the IWT; it notes “The provisions of this treaty may from time to time be modified by

a duly ratified treaty concluded for that purpose between the governments”. Besides, the treaty in

its Preamble promotes the spirit of goodwill and friendship for utilization of the Indus system of

rivers and notes that “concerning the use of these waters and of making provision for the

settlement, in a cooperative spirit, of all such questions as may hereafter arise in regard to the

interpretation or application of the provisions agreed upon herein”.

1.3 Key words

Indus Water Treaty, Future cooperation

2.0 Issues and Stakeholders

The Indus water treaty was signed six decades ago. The treaty is mainly based on the division of

surface water rivers, it did not deal with other important subjects like ground water, water quality,

sedimentation, environmental impacts, and watershed management which therefore translates that

there is a scope of improvement.

Stakeholders

Pakistan, India, World Bank

Indirect Stakeholders

Afghanistan, China

3.0 Background of the Indus Water Treaty

Water relations between Pakistan and India have a typical textbook style rift of upper and lower

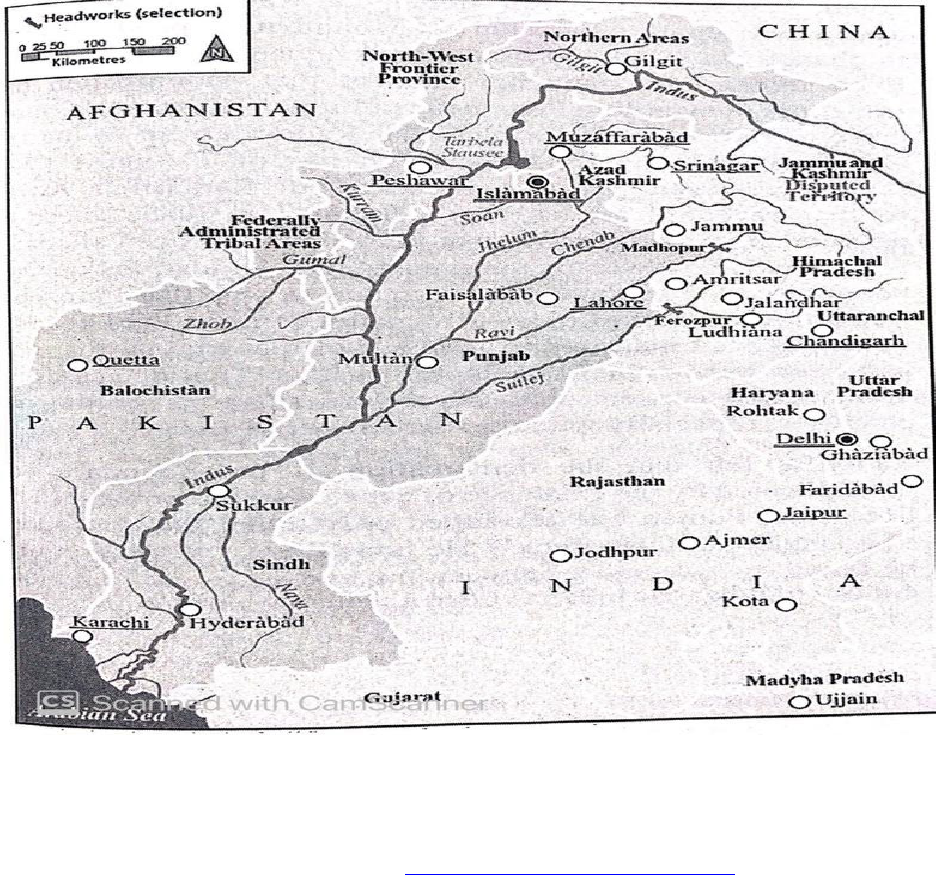

riparian’s. When Pakistan and India emerged as separate nations in 1947, the two headworks at

Ferozepur and Madhopur on Sutlej and Ravi Rivers respectively which were very close to border

fell into the Indian side of the partition boundary (Figure-1). Water in the Irrigation canals at the

Pakistani side on these rivers were controlled from these headworks. On April 1

st

, 1948; India

stopped water from these headworks which affected 1.7 million acres of agricultural land, livestock

and the lives of millions of people who were depended on water of the canal system on these

3

headworks. On another front, Pakistan and India were having a serious conflict over the territory

of Kashmir. Sensing an imminent danger of a bloody war between Pakistan and India, In 1952,

The President of World Bank Mr. Eugene Black offered Banks support to the Prime Minister’s of

the two countries to formulize an agreement with the objective to carry out specific engineering

measures for enhanced and effective management of water. After an almost decade long series of

negotiations, the treaty was signed on 19 September 1960. According to that treaty Pakistan

received exclusive rights of the three western rivers the Jhelum, the Chenab and the Indus while

India got three eastern rivers the Beas, the Sutlej and the Ravi.

The treaty allowed India to use western rivers water for limited irrigation use and unlimited use

for power generation, domestic, industrial and non-consumptive uses, such as navigation, floating

of property, and fish culture, while laying down precise regulations for India to build projects.

Figure-1

Source: Hydro-Diplomacy: Preventing water wars between Nuclear armed Pakistan and India by

Ashfaq Mehmood. © IPS Press. All rights reserved. This content is excluded from our Creative

Commons license. For more information, see https://ocw.mit.edu/help/faq-fair-use/.

4

4.0 Limitations of the Treaty and Scope for improvement

4.1 Agricultural Use by India from the western rivers

The term “Agricultural Use” means the use of water for irrigation, except for irrigation of

household gardens and public recreational gardens (1). Withdrawals from specified canals (Ranbir

and Pratab) on the Chenab main were limited in terms of quantity of water in cusecs in different

periods in a year with a few exceptions. Besides, India could continue to irrigate those areas from

the western rivers which were so irrigated on the effective date after treaty. Moreover, India was

allowed to make further withdrawals from the western rivers to the extent it may consider

necessary to meet the irrigation needs of the areas specified in the Annexure-C of Indus Water

Treaty. No limit was placed on the quantity of withdrawal. It leaves the volume to be withdrawn

solely to the discretion of India and does not impose any condition regarding efficiency in use of

water.

4.1.1 Scope for improvement

With the growing stress on water and variability of flows in the rivers, this provision of treaty

would allow India to use traditional farming practicing by growing high delta crops on the western

rivers while it might put stress on water availability across the border. It is suggested that

improvement is made in treaty can be made by promoting efficient use of water and limiting the

withdrawal of water in terms of specified quantity worked out based on scientific calculations

required to be employed if crops are cultivated using high efficiency irrigation systems.

Through a mutual understanding, India and Pakistan must agree on a time-frame for the storage

and release of water so that the availability of water for irrigation and energy generation remains

optimal through mutually negotiated trade-offs. (2)

4.2 Ground water

The Indus river basin represents an extensive groundwater aquifer, covering a gross command area

of 16.2 million ha (3). According to a recent NASA survey the Indus Basin is the second-most

overstressed on the planet, and its water levels falling by 4-6 mm/year. Over extraction of ground

water with a slow rate of recharge is putting the bordering areas under extreme stress. Farmers are

free to install tube wells and extract unlimited amounts of groundwater without regard to the

detrimental effect on the aquifer. Information collected through Gravity Recovery and Climate

Experiment (GRACE) NASA suggests that groundwater extraction in India might be affecting

groundwater in Pakistan

(4).

4.2.1 Scope for improvement

The Indus Water Treaty is based on division of surface water and there is no clause to deal with

ground waters and transboundary aquifers. Improvement in treaty can be made by first employing

regulations in ground water withdrawal by both countries, sharing of data regarding rate of

discharge and recharge and monitoring transboundary aquifers and curbing the over extraction of

ground water.

5

4.3 Climate Change

The Indus River system gets more than 80% water from karakoram and Hindu-kush-Himalayas

glaciers. During the period 1981 to 2005 the decadal mean temperature rise over Pakistan was

0.39

o

C as compared to 0.177

o

C for the globe which shows that the warming over Pakistan was

twice as fast as global mean temperature.

The climate projections by various studies strongly suggest the following future trends in the Indo-

Pakistan subcontinent.

1) Decrease in the glacier volume and snow cover leading to alterations in the seasonal flow

pattern of Indus River system.

2) Increase in the formation and burst of glacial lakes. A GLOF event on February 9th, 2021

in India's northern state of Uttarakhand killed at least 32 people and trapped workers in

underground tunnels

(5). A similar event occurred after a glacier in Chitral, Pakistan

exploded overnight resulting in washing away of five bridges and the Azghor valley road.

Considerable damage was also done to the 108 MW Golen Gol Hydropower project.

3) Higher frequency and intensity of extreme climate events coupled with irregular monsoon

rains causing frequent floods and droughts.

4) Greater demand of water due to increased evapotranspiration rates and elevated

temperatures

The above trends reveal that Climate Change will seriously impact the future water patterns.

Specially, Pakistan which is heavily dependent on this single river system for its agriculture.

Agriculture generates 23% of Pakistan’s national income and about 68% of the population living

in rural areas are dependent on agriculture for their livelihood” (Bhatti and Farooq 2014).

4.3.1 Scope for improvement

The Indus Water Treaty was signed more then Six decades ago, the average water flows and the

climatic conditions were fairly constant. In general, little emphasis was laid on the topic of climate

change.

India and Pakistan are both in a perilous position surrounding water availability. Both countries

are facing a shortage of water and it is expected that they will continue to experience this.

Therefore, “it would be beneficial if both countries recognized their cooperative potential and

combined their resources and expertise to make mutually beneficial decisions” (Ahmad 2011).

One such step would be to incorporate the impacts of climate change on future water availability

in the Indus Water Treaty.

4.3.2 Dealing with Climate Crisis for attaining mutual gains

It is clear that Climate Change is going to affect both India and Pakistan, besides the region as a

whole. In this regard, in order to extract mutual benefits, the two countries may agree to form a

6

Climate Change Commission in collaboration with international experts to cooperate in

undertaking various studies on effects of climate change, mitigation measures and preparation of

a plan of action. Moreover, the commission could undertake flood forecasting, early warning

systems and watershed management.

4.4 Run off River Hydropower Projects and the Jammu & Kashmir Issue

The territorial control over Kashmir has always been the bone of contention between India and

Pakistan. Many experts believe that one of the underlying interests over the possession of Kashmir

is water. Indus, Jhelum and Chenab run through the territory of Jammu and Kashmir and having

control over a part of territory in Jammu and Kashmir, India became the upper riparian on these

rivers.

Annexure-D, Part-3 of the Indus Water Treaty has laid down provisions for India to construct new

run of river power plants (post 1960). As per treaty Run-of-River Plant” means a hydro-electric

plant that develops power without Live Storage as an integral part of the plant, except for Pondage

and Surcharge Storage (6). India started building major power projects in J&K in 1970s. The

projects which have been under dispute since then are Salal Hydroelectric Project, Baglihar

Hydroelectric Project, Wullar Barrage and Kishenganga Hydroelectric Project. A number of these

projects are located on river Chenab. Pakistan feels threatened that the cumulative effect of these

dams is going to provide India a total control over water flows in Chenab.

It is the cumulative impact of live storages that is feared in Pakistan. John Briscoe, Professor of

the Practice of Environmental Health at Harvard observes, “the cumulative live storage will be

large, giving India an unquestioned capacity to have major impact on the timing of flows into

Pakistan. Using Baglihar as a reference, simple back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that

once it has constructed all the planned hydropower plants on the Chenab, India will have an ability

to effect major damage on Pakistan. (7)

4.4.1 Scope for improvement

Taking the example of Baghlihar ROR project from the above-mentioned disputed projects built

by India with the gross storage capacity of 321,048 acre feet. If India completely depletes the

Baghlihar storage and start filling in the lean flow period of November, December and January

months, it can dry up River Chenab for about 26 days. Therefore, the provisions of Annexure-D

of the treaty need to be looked into in respect of future hydropower plants planned by India.

4.5 Water Quality

It has been observed that very little resources are being spent by India and Pakistan regarding

wastewater treatment. Official figures show that 78 per cent of the sewage generated in India

remains untreated and is disposed of in rivers, groundwater or lakes (8) and these figures are even

worse for Pakistan. However, in case of Indus river system, the upper riparian has additional

responsibilities.

7

High concentration of chemical pollutants due to extensive use of fertilizers and pesticides in

agricultural fields, industrial wastes and increase in domestic effluent due to rapid urbanization

around water bodies are polluting the surface drainage channels entering Pakistan (9). In particular,

there are serious concerns in the deteriorating quality of the waters of Hudiara drain (10) which

enters Pakistan from its eastern border at Burki and joins River Ravi. Polluted water is affecting

the quality of the aquifers as well as drinking in agriculture water. It is becoming serious health

and livelihood issue for Pakistan it is also affecting livestock, river habitat and the environment in

general.

4.5.1 Scope for improvement

The issue of Water pollution is bound to escalate because of its serious environmental implications.

It is, therefore, important to address the issue of water quality before it becomes a source of

escalation between the two countries. The IWT treats this aspect cursorily, providing only that

“each party declares its intention to prevent, as far as practicable, undue pollution” (Art. IV (10)).

In this aspect the commissioners on both sides can look into incorporating (as supplementary

annexure within the limitations of the treaty) the guidelines laid in the UN Water Courses

Convention that gives comprehensive treatment to the protection and presentation of international

watercourses and related ecosystems (Part IV: Arts. 20–23).

4.6 Involvement of other Transboundary river basin countries

The Tibetan plateau which lies in China is often called the “Third Pole”, owing to its glacial

expanses and vast reserves of freshwater. The Indus river also originates from the Tibetan plateau.

With the recent rift between India and China over the territorial control of Ladakh valley, concern

have rosed in India that China could exploit the flow of rivers flowing downstream towards India

including the Indus.

Similarly, Pakistan and Afghanistan have no water sharing agreement for the Kabul River, an

important tributary of the Indus which supplies up to 17% of Pakistan’s total water. As Afghanistan

strives to develop its hydropower, with the help of Indian finance, this could instigate a whole new

conflict on the Indus itself (11).

4.6.1 Scope for improvement

It is clear that all four countries are dependent on each other for their availability of waters.

Expanding the water sharing agreement to include Afghanistan and China and discussing joint

solutions could initiate an atmosphere of trust between the counties. Neither of these countries

should be thinking about weaponizing water. Specially for countries like Pakistan and India who

are already heading towards water scarcity, enhanced cooperation in the basin could lead to a

positive impact on the overall water availability.

5.0 Key Questions

8

5.1 Given the persistent distrust among Pakistan and India; How the existing conflict

resolution mechanism can be improved using the Mutual gains approach of the Water

Diplomacy Framework?

There is no denying that relations between Pakistan and India are not harmonious and a

considerable element of distrust exist between the two countries while dealing with Transboundary

water issues. As part of Indus Water Treaty, Permanent water commissions (PWCs) are in place

to settle any disputes on Indus waters. However, the mode of business conducted in the PWCs in

typically bureaucratic set up of the PWCs is usually governed by politically motivated decisions

rather than rational technical grounds.

Perhaps that is why the riparian have never been able to solve any major conflict at the level of

PWCs and had to sought third-party mediation for the resolution. Even the disputes like

Kishanganga and Baglihar had to be mediated by the World Bank. Thus, frequently seeking the

mediation services of International Court of Arbitration on every issue seriously jolts the mutual

trust. A complete failure to resolve any major dispute at the level of PWCs explains the inability

of both riparian to address the local disputes primarily due to dominant political interests which

are served at the cost of mutual trust (12).

So, in this challenging environment, how can mutual gains approach be employed to improve the

conflict resolution mechanism between the two countries? One way of confidence building

measure or future conflict resolution mechanism could be establishing a Joint research center

headed by an appointee of United Nations and comprising technocrats, climate experts, water

management experts and scientists from both Pakistan and India as well as from other nations

appointed by United Nations on term basis on the following pattern. The involvement of other

nations would be a great value addition. When treaty was signed in 1960, value was created to the

treaty when both countries developed major water infrastructure in the Indus river basin with the

generous donations of friendly nations. However, in this era, the interest of global community will

be greater as India and Pakistan are now two nuclear powers. Any misadventure caused by a

conflict by any of these two countries could lead to regional as well as global instability. “To our

knowledge no other water treaty involves two rival nuclear power nations. It will be easier to unite

international community on this issue concerning global security” (12). Hence technical and

financial resources from other countries could be handy in the case of IWT.

9

With the inclusion of neutral experts, it would be possible to collect and disseminate real time flow

data, identification of impacts of climate change on river flows including impacts on rivers due to

anthropogenic activities by both countries, maintaining ecological integrity of the basin,

sustainable management of transboundary rivers and smooth functioning of the treaty in general.

Unlike Permanent Water Commissioners, “the scientific community will execute their conclusions

from the analyses based on reliable data. With the usage of reliable data and established

methodologies for data examination, the room for political biasness will be very small” (11). Once

mutual trust is established through this mechanism, the appointed head by United Nations could

get recommendations generated by experts implemented through head of states of the two

countries.

5.2 What considerations can be given to incorporating collaborative adaptive management

(CAM)? What efforts have the parties made to review and adjust a solution or decision over

time in light of changing conditions?

As the Indus Water Treaty was conceived during the 1950’s, focus on issues like climate change,

population increase, new hydropower development, water quality etc was not paid. The article VII

of the IWT does have a clause for “future cooperation” which recognizes that the two countries

“have a common interest in the optimum development of rivers, and, to that end, they declare their

intention to co-operate, by mutual agreement, to the fullest possible extent” (13).

In particular, the article on future cooperation envisages cooperation in setting up hydrologic and

metalogical observation stations, new drainage works and in undertaking engineering works on

the rivers at the request of either party, by mutual agreement. The declaration of intent to cooperate

by mutual agreement is a very important and fundamental statement for future cooperation. This

makes the scope of future cooperation very wide (14). Despite the historical trust deficit and a

couple of deadly wars between the two countries, the Indus Water Treaty is still in place and is

followed for managing the transboundary waters. Thus, Expanding the treaty to tackle recent

challenges like climate-induced water variability, groundwater or environmental considerations

can be addressed within the scope of Indus Water Treaty.

Headed by United Nations

Water resource manager - India

Climate experts - India

Data Base management experts -

India

Treaty specialists - India

Water resource manager –

Neutral

Climate experts - Neutral

Data Base management experts -

Neutral

Treaty specialists - Neutral

Water resource manager -

Pakistan

Climate experts - Pakistan

Data Base management experts -

Pakistan

Treaty specialists - Pakistan

10

5.3 What mechanisms beyond simple allocation can be incorporated into transboundary

water agreements to add value and facilitate resolution?

One of the fundamentals of the treaty is the division of Eastern and Western rivers rather than

sharing of rivers. The governments of the two countries need to re-examine the principles of water

sharing followed in the Indus Water Treaty. Principle of division in the treaty should be replaced

by cooperation and upper and lower riparian rights should replace the heterogeneous application

of water sharing principles in eastern and western rivers. This will ensure justice to all

communities. Replacing the strict territorial division of the basin by upper and lower riparian rights

will also pave way for the two countries to jointly execute projects of common interest.

6.0 Way Forward

Many experts regard the treaty as sacrosanct. Massive infrastructure has been built on both sides

of the border post treaty and given the complexities involved in the relationship between Pakistan

and India, the idea of Indus Water Treaty (II) might not work. However, the existing water issues

specially impacts of climate change are bound to escalate in the wake of increasing population,

industrialization, and growing demand from various sectors. The Article VII of the IWT does have

a clause for “future cooperation”; Moreover, Final Provisions, article XII, Clause 3 of the IWT;

notes that “The provisions of this treaty may from time to time be modified by a duly ratified treaty

concluded for that purpose between the governments”.

Decades ago, when World Bank took the lead in resolving the water dispute between the two

countries based on knowledge regarding data, hydrology and engineering, the approach of parties

was changed from sentiments to logic. The Bank was able to break the dead lock between Pakistan

and India by agreeing them to sign the Indus Water Treaty. It is high time again for World Bank

to step up with all its scientific, engineering, law and diplomacy capabilities and offer Pakistan

and India to sit on table to address the issues discussed in this case study remaining within the

provisions of Article VII and XII of the IWT. It will be important to invite experts from China and

Afghanistan who also share the Indus River Basin part of the discussions as these regional players

are becoming more and more relevant with the passage of time.

7.0 References

1. Indus water treaty, 1960, Article I, Definitions

2. Revisiting the 1960 Indus Water Treaty, Hamid Sarfaraz

3. India, Pakistan, Water, and the Indus Basin: Old Problems, New Complexities Ahmad

Rafay Alam

4. Groundwater laws in the Indus basin, LEADS Pakistan.

5. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-56007448

6. Indus Waters Treaty, Annexure D, Part 1 – definitions (g), Page 1.

11

7. Power Projects in Jammu & Kashmir: Controversy, Law and Justice by Zubair Ahmad Dar,

LIDS Working Papers 2011-2012 Harvard Law and International Development Society.

8. https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/waste/-78-of-sewage-generated-in-india-remains-

untreated--53444

9. Dr. Shahid Ahmad, IUCN, 2013. Beyond Indus Water Treaty.

10. Shukla, K.S. 2009. Indian River systems and pollution.

11. How India and Pakistan are competing over the mighty Indus river; Fazilda Nabeel

12. Muhammad Uzair Qamar, Muhammad Azmat and Pierluigi Claps; Pitfalls in

transboundary Indus Water Treaty: a perspective to prevent unattended threats to the global

security, 2019.

13. Indus water treaty, 1960, Article VII

14. Hydro-Diplomacy: Preventing water war between Nuclear armed Pakistan and India by

Ashfaq Mahmood.

12