Page 1 of 68

City of Los Angeles

Traffic Enforcement Study and

Outreach Report

April 2023

Item #4a

Page 2 of 68

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Executive Summary ............................................................................... 3

II. Context And Framing ............................................................................. 4

III. Project Overview .................................................................................. 10

IV. Research Findings ............................................................................... 13

V. Recommendations ............................................................................... 62

VI. Appendices .......................................................................................... 68

Page 3 of 68

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Page 4 of 68

II. CONTEXT AND FRAMING

A. HISTORY AND ORIGINS OF TRAFFIC

ENFORCEMENT

This report explores options for the City of Los Angeles to pursue “alternative models and

methods . . . to achieve transportation policy objectives” without relying heavily on armed law

enforcement.

1

In a motion presented to the Ad Hoc Committee on Police Reform,

councilmembers noted that the impetus for this study is a legacy of racialized policing in the City

of Los Angeles and nationwide, where police officers “have long used minor traffic infractions as

a pretext for harassing vulnerable road users and profiling people of color.”

2

In keeping with

Council’s stated intent, this section offers an overview of the history of policing. It summarizes

how modern policing in the U.S. evolved from the colonial era and provides context for twentieth

and twenty-first century policing in Los Angeles. This history is not exhaustive; it is intended to

ground readers in the larger historic and social contexts that inform this report’s analysis and the

accompanying recommendations.

1. Historic Origins of Policing

In ancient societies, policing evolved to protect the economic interests of the upper classes.

3

This system was predicated on differential rights based on social status, including

socioeconomic standing, conditions of servitude, property ownership, and gender.

2. Policing as a Tool to Regulate and Restrict the Movement of Black

Americans, Indigenous Communities, and Migrants

The genesis of modern policing in the United States can be traced back to slavery in colonial

America, where the economy relied on the involuntary labor of enslaved Africans and their

descendants.

4

Southern landowners established slave patrols to maintain this system of chattel

slavery. The patrols aimed to control the population of Black Americans by capturing people

attempting to flee the conditions of forced labor, and by maintaining a system of terror that

1

Los Angeles City Council (2021). Council File: 20-0875 – Transportation Policy Objectives/Alternative

Models and Methods/Unarmed Law Enforcement. Council Adopted Item. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from

https://cityclerk.lacity.org/lacityclerkconnect/index.cfm?fa=ccfi.viewrecord&cfnumber=20-0875

2

Los Angeles City Council (2020). Council File: 20-0875 – Transportation Policy Objectives/Alternative

Models and Methods/Unarmed Law Enforcement. Motion Document(s) Referred to Ad Hoc Committee on

Police Reform. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from

https://cityclerk.lacity.org/lacityclerkconnect/index.cfm?fa=ccfi.viewrecord&cfnumber=20-0875

3

https://biz.libretexts.org/Courses/Reedley_College/Criminology_1__Introduction_to_Criminology_(Cartwr

ight)/01%3A_Perspectives_on_Justice_and_History_of_Policing/1.01%3A_Early_History_of_Policing

4

Bhattar, K. (2021). The History of Policing in the US and Its Impact on Americans Today. Retrieved from

https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/2021/12/08/the-history-of-policing-in-the-us-and-its-impact-on-

americans-today/

Page 5 of 68

sought to quell persistent Black resistance.

5

During Reconstruction, “slave patrols were

replaced by militia-style groups” who were charged with enforcing Black Codes that “restricted

access to labor, wages, voting rights,” and limited the movement of formerly enslaved people.

6

Although these patrols and militias do not reflect the municipally-organized police forces that are

common today, it is important to recognize that their purpose was largely to regulate and restrict

the movement of Black Americans – a goal that was often achieved through force, threats, and

intimidation.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, municipalities began establishing police

forces that resemble modern police departments. However, police were generally not the lead

entity charged with enforcing social norms. In this era, “communities largely policed themselves

through customs and common-law suits.”

7

The role of patrolling officers in the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries largely focused on policing “those on the margins of society:

drunks, vagrants, prostitutes, and the like.”

8

In the U.S., this system of enforcement was often

racialized and sought to constrain opportunities and the physical movement of non-whites.

During this era, Native Americans, Chinese and Latino migrants, as well as Black Americans in

Los Angeles were specific enforcement targets. Local law enforcement used selective

enforcement of public order laws to arrest disfavored populations. In the case of Chinese

residents, local representatives of federal law enforcement authorities enforced racist and

xenophobic federal immigration laws – namely, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and its

successor, the 1892 Geary Act.

9

A mixture of racial animus, economic conditions, and the need to quell moral panics influenced

which marginalized groups were on the receiving end of heightened scrutiny. In the latter half of

the nineteenth century, local law enforcers (i.e., marshals and rangers) subjected Native

Americans to “aggressive and targeted enforcement of state and local vagrancy and drunk

codes” at the behest of the Los Angeles Common Council.

10

During the Panic of 1893, the Los

Angeles Federated Trades Union coordinated with U.S. marshals to conduct deportation raids

targeting Chinese residents.

11

Amidst a labor shortage in 1917, Los Angeles’ mayor “ordered

the chief of police to force unemployed Mexicans back to work by ‘arrest[ing] all Mexicans

5

Bhattar, K. (2021). The History of Policing in the US and Its Impact on Americans Today. Retrieved from

https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/2021/12/08/the-history-of-policing-in-the-us-and-its-impact-on-

americans-today/

6

NAACP (n.d.). The Origins of Modern Day Policing. Retrieved on March 14, 2023 from

https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/origins-modern-day-

policing#:~:text=The%20origins%20of%20modern%2Dday,runaway%20slaves%20to%20their%20owner

s.

7

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1624

8

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1624

9

Hernández, K.L. (2017). City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los

Angeles 1771 – 1965. The University of North Carolina Press

10

Hernández, K.L. (2017). City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los

Angeles 1771 – 1965. The University of North Carolina Press: 36.

11

Hernández, K.L. (2017). City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los

Angeles 1771 – 1965. The University of North Carolina Press: 82-83.

Page 6 of 68

unemployed in the Plaza District, as vagrants.’”

12

During the Prohibition era, the Central Avenue

district was a predominantly Black neighborhood where “gambling, drinking, prostitution, and

late-night clubs” were permitted to thrive under a rampantly corrupt Los Angeles Police

Department (LAPD).

13

While the LAPD has evolved, the description of how this majority-Black

community was policed in the 1930s – and the effects said policing had on residents –

describes the reality that many low-income Black and Brown communities in Los Angeles face

today:

“[T]he heavy concentration of LAPD officers in the Central Avenue District

exposed both African American men and women residing in the district to

high levels of everyday policing on public order charges. The result was serial

arrests and constant cycling in and out of the local jails for African American

residents, especially the poor and working class who lived much more of their

lives in public than the economically secure.”

14

3. How Cars Transformed Policing

The twentieth century saw the rise of the automobile as a primary mode of travel; with it, came a

transformation in how the public interacted with police officers. In many respects, the ubiquity of

the automobile – and the reliance on armed law enforcement to address traffic safety concerns

– meant that traffic stops “became one of the most common settings for individual encounters

with the police.”

15

Driving presented new hazards in public spaces, leading local governments to past a raft of

laws to regulate space, assign rights of way, and govern the use of vehicles.

16

The language in

these new laws was often vague. For example, California’s Motor Vehicle Act of 1915

“prohibited driving ‘at a rate of speed . . . greater than is reasonable and proper.’”

17

Determining

what was considered “reasonable” or “proper” necessarily relied on the discretion of the

enforcing body. But police enforcement of these norms was not a foregone conclusion, with

some police departments actively resisting the task of enforcing traffic laws.

18

In some cases,

“police chiefs complained that traffic control was ‘a separate and distinct type of service’ – i.e., it

12

Hernández, K.L. (2017). City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los

Angeles 1771 – 1965. The University of North Carolina Press: 148.

13

Hernández, K.L. (2017). City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los

Angeles 1771 – 1965. The University of North Carolina Press: 167.

14

Hernández, K.L. (2017). City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los

Angeles 1771 – 1965. The University of North Carolina Press: 171-72.

15

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1625

16

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1635

17

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1636

18

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1637

Page 7 of 68

was not their job.”

19

While separate bureaucracies had been created to enforce certain types of

laws (e.g., postal inspectors and secret service agents), “a lack in political will to foot the bill for

yet another bureaucratic entity" meant that traffic regulation would fall on the police.

20

This represented an expansion of police powers over the traveling public. It embedded a system

where traffic safety issues are first and foremost handled by police and designated as criminal

matters, and it established the broad discretionary powers that police departments use when

enforcing voluminous and complex traffic safety laws. Indeed, it represented a transformation in

how police and policing showed up in the daily lives of all Americans.

21

Given the history of law

enforcement in the U.S., the implications for marginalized groups (e.g., Black communities,

Indigenous populations, Latino communities, migrants, low-income communities) were

particularly dire.

B. LOS ANGELES’ MODERN CONTEXT

In Los Angeles, police brutality against Black residents during traffic stops has been tied to

multiple uprisings, leading to local, state, and national calls for police reform. In the 1960s, the

Watts Rebellion made headlines as part of the larger, nationwide movement against police

brutality. The arrest of a 21-year-old Black man, Marquette Frye, for drunk driving close to the

Watts neighborhood, and the ensuing struggle, sparked six days of unrest. The uprising resulted

in 34 deaths, over 1,000 injuries, nearly 4,000 arrests, and the destruction of property valued at

$40 million.

22

As a result of the rebellions, Governor Jerry Brown appointed a commission to

study the underlying factors and identify recommendations in various policy areas, including

police reform. In its report, the Commission cited the lack of job and education opportunities and

the resentment of the police as key contributors to the uprisings, which were ignited by the

brutal actions taken against Frye during the traffic stop.

23

The report also recommended a

strengthened Board of Police Commissioners to oversee the police department. Likewise, the

report supported recruiting more Black and Latino police officers as a means of improving the

community-police relationship.

24

19

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1637

20

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1637-8

21

Seo, S. (2016). The New Public. Yale Law Journal. Retrieved on April 3, 2023 from

https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3825&context=faculty_scholarship

: p.

1638

22

Stanford University. (2018, June 5). Watts Rebellion (Los Angeles). The Martin Luther King, Jr.,

Research and Education Institute. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from

https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/watts-rebellion-los-angeles

23

California. Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots. (1965). Violence in the city: An end or a

beginning?: A report. HathiTrust. The Commission. Retrieved 2023, from

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081793618&view=1up&seq=12.

24

California. Governor's Commission on the Los Angeles Riots. (1965). Violence in the city: An end or a

beginning?: A report. HathiTrust. The Commission. Retrieved 2023, from

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081793618&view=1up&seq=12.

Page 8 of 68

Despite the lessons gleaned from the Watts Rebellion, the 1990s saw another uprising in

response to police brutality during a traffic stop. In 1992, Rodney King, a 25-year-old Black man,

was brutally beaten and arrested by four police officers and later charged with driving under

influence.

25

The four officers were charged with excessive use of force but were all acquitted

one year later. The widely circulated video of King’s beating and the news about the officers’

acquittal ignited days of violent unrest in the city, especially in the Historic South Central

neighborhood. The city employed a curfew and the National Guard to respond to the uprising.

While the 1992 unrest shared parallels with the Watts uprisings, “the conflagration that took hold

after the King trial wasn’t constrained to that neighborhood and was not restricted to Black

Angelenos.”

26

Instead, the ensuing unrest “constituted the first multiethnic class riots in

American history an eruption of fury at the socioeconomic structures that excluded and

exploited so many in Southern California.”

27

More recently, the 1999 Rampart Scandal exposed widespread police corruption in the anti-

gang unit of Los Angeles Police Department’s Rampart Division. LAPD officers were concealing

use of force incidents in their attempts to counteract gang crimes. These incidents

disproportionately affected the city’s low-income Black and Brown communities. Considering

this, and a series of preceding scandals dating back to the Rodney King beating, the city

entered a “consent decree,” promising to adopt scores of reform measures under the

supervision of the Federal Court. In an evaluation of the effectiveness of the decree,

researchers found that the strong police leadership and oversight brought by the consent

decree have made policing in Los Angeles more respectful and effective, although there is still

more to be done.

28

C. LOS ANGELES CITY COUNCIL MOTION +

IMPETUS FOR THIS STUDY

In 2020, the murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by a Minneapolis police officer led to

protests across the country, including in Los Angeles.

29

As a result of local protests and

persistent, long-sought calls for non-law enforcement alternatives, the Los Angeles City Council

passed a motion in October 2020. The Council Motion (CF-20-0875) directed the Los Angeles

Department of Transportation (LADOT) to conduct a study that evaluates opportunities for

unarmed traffic enforcement in the city.

25

Krbechek, A. S., and Bates, K. G. (2017, April 26). When La erupted in anger: A look back at the

Rodney King Riots. NPR. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from

https://www.npr.org/2017/04/26/524744989/when-la-erupted-in-anger-a-look-back-at-the-rodney-king-

riots

26

Muhammad, I. (2022). What Were the L.A. Riots? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved on April 4,

2023 from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/04/28/magazine/la-riot-timeline-photos.html

27

Muhammad, I. (2022). What Were the L.A. Riots? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved on April 4,

2023 from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/04/28/magazine/la-riot-timeline-photos.html

28

Stone, C., Foglesong, T., and Cole, C. M. (2009). (rep.). Policing Los Angeles Under a Consent

Decree: The Dynamics of Change at the LAPD. Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved 2023, from

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/policing-los-angeles-under-consent-decree-dynamics-change-

lapd.

29

City of Minneapolis. (2023). 38th and Chicago. 38th and Chicago - City of Minneapolis. Retrieved

March 7, 2023, from https://www.minneapolismn.gov/government/programs-initiatives/38th-chicago/

Page 9 of 68

Since the launch of this study in February 2022, several developments have influenced the

study’s findings and approach. In March 2022, the Los Angeles Police Commission approved a

policy limiting pretextual stops to safety-related incidents and setting requirements for officers

that pursue these types of stops.

30

Further, in October 2022, City Council approved a motion to

explore an Office of Unarmed Response and Safety for the city.

31

Tragically, incidents of police brutality during traffic stops have also continued during the study

period. In early 2023, multiple LAPD officers held down and tased Keenan Anderson, a 31-year-

old Black man, repeatedly after he sought help from the police following a traffic collision. The

interaction ended in Anderson’s death.

32

At the time of this writing, the investigation into Keenan

Anderson’s death is ongoing, but communities have already responded by reiterating calls to

change LAPD policy and to rethink the relationship between police officers and the communities

they serve.

33

Likewise, Anderson's death – one of three fatalities stemming from the LAPD's use

of force in a one-week period – sparked fresh calls for police reform from the Mayor and

members of City Council.

34

More recently, LAPD’s largest employee union noted that they are

“looking to have officers stop responding to more than two dozen types of calls, transferring

those duties to other city agencies while focusing on more serious crimes.”

35

30

Rector, K. (2022, March 2). New limits on 'pretextual stops' by LAPD officers approved, riling police

union. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-

03-01/new-limits-on-pretextual-stops-by-lapd-to-take-effect-this-summer-after-training

31

KCAL-News Staff. (2022, October 8). La City Council to consider 'office of unarmed response'. CBS

News. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.cbsnews.com/losangeles/news/la-city-council-to-

consider-office-of-unarmed-response/

32

Olson, E. (2023, January 21). A $50m claim is filed against LA over the death of a man who was tased

by police. NPR. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.npr.org/2023/01/14/1149132089/keenan-

anderson-patrisse-cullors-lapd-body-cam-footage

33

Winton, R. (2023, January 18). LAPD officers tased Keenan Anderson 6 times in 42 seconds. Los

Angeles Times. Retrieved March 20, 2023 from https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-01-18/lapd-

tasing-of-keenan-anderson-brings-scrutiny-to-police-policy

34

Jany, L. and Winton, R. (2023, February 20). Mayor Bass calls for overhaul of LAPD discipline system,

more detectives to work cases. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-02-20/mayor-bass-lays-out-plan-for-lapd-public-safety

35

Zahnisher, D. (2023, March 1). LAPD should stop handling many non-emergency calls, police union

says. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 20, 2023 from https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-

03-01/lapd-officers-want-to-stop-responding-to-nonviolent-calls

Page 10 of 68

III. PROJECT OVERVIEW

A. CITY WORKING GROUP

The City Working Group includes representatives from City of Los Angeles departments named

in the Council Motion (CF-20-0875) and directed by Council to perform the work (See Appendix

A for full Council Motion). Participating City departments include Department of Transportation

(LADOT), Police Department (LAPD), City Administrative Officer (CAO), City Attorney, and

Chief Legislative Analyst (CLA). Members of the working group were directed to use their

knowledge of the Los Angeles Municipal Code, California Vehicle Code, and other relevant

traffic laws to inform the direction of the study. The City Working Group informed the

development of the Request for Proposals, supported LADOT in soliciting and selecting

members of the Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task Force, and reviewed draft

project deliverables. The working group, LAPD in particular, consistently attended Task Force

meetings, made presentations to the Task Force on various topics related to traffic enforcement,

and provided data sources to the consultant team to inform the quantitative and qualitative

analyses. The City Attorney’s Office attended Task Force meetings, provided legal guidance on

an ongoing basis, and guided LADOT on how to approach issues related to the Task Force and

the Brown Act. The working group reviewed and provided feedback at various stages of the

study.

B. CONSULTANT TEAM

The City Working Group selected the consultant team for this study. The team consisted of the

following firms with the associated scopes of work:

•

Estolano Advisors: Consultant team lead responsible for providing Task Force meeting

facilitation support.

•

Equitable Cities: Research team responsible for conducting a case study literature

review, quantitative analysis, and qualitative analysis.

•

Nelson\Nygaard: Research team support responsible for leading the expert interviews,

supporting Equitable Cities with the focus groups, and identifying next steps for study

outreach.

•

Law Office of Julian Gross: Legal team responsible for conducting interviews and

research on legal questions arising from the study’s proposed recommendations.

The consultant team developed the study and executed the scopes described above in

collaboration with the City’s Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task Force (See Section

III.C).

Page 11 of 68

C. TRAFFIC ENFORCEMENT ALTERNATIVES

ADVISORY TASK FORCE

1. Background and Task Force Selection

The City Council motion directed LADOT to develop an advisory task force to provide

recommendations on traffic safety alternatives. The resulting Traffic Enforcement Alternatives

Advisory Task Force provided guidance and feedback on the consultant team’s deliverables and

co-developed study recommendations with the consultant team. The Task Force met 11 times

via Zoom from June 2022 through April 2023.

The Task Force consisted of thirteen (13) members with personal and professional experience

in traffic safety, public health, mental health, racial equity, academia, and criminal justice (See

Appendix B for a full Task Force roster). Members were selected through a two-step process,

which began with a Google Form application, followed by interviews with representatives from

the City Working Group and the consultant team (See Appendix C for the application form). To

recruit participants, LADOT conducted outreach via its existing listserv. The City received 76

applications and interviewed 11 applicants to learn more information. The City Working Group

ultimately selected 13 applicants to serve as Task Force members. Eight applicants were

selected on the strength of their initial application; four members went through an interview

process conducted by the City Working Group; and one member was appointed from the

Community Police Advisory Board (C-PAB). A minimum of three (3) slots were made available

for members of the C-PAB, but only one member expressed interest and responded to the call

to participate in the Task Force. The applicants were selected based on selection criteria and

score.

2. Public Task Force Meetings

The Task Force served as a public body, which required the City and members to comply with

requirements outlined in California’s Ralph M. Brown Act. These requirements included

ensuring that the City posted meeting materials at least 72 hours prior to each meeting and

providing time during each meeting for public comment. Task Force members also needed to

identify a President and Vice President, whom they elected during the September 2022 meeting

(See Appendix B for elected members). Task Force President and Vice President were

responsible for facilitating meetings, including calling for the start of each meeting, calling for

votes, monitoring timing for general public comment, and calling for meeting adjournment. The

consultant team facilitator was also available to facilitate specific agenda items, dependent on

the content.

To comply with Brown Act requirements for teleconferencing, Task Force meetings took place

on a roughly monthly basis and lasted between 90 minutes and two hours. Meetings covered a

range of topics related to the study, including the following (See Appendix D for Task Force

meeting summary):

(1) Task Force responsibilities and administrative requirements

(2) Problem statement discussion

Page 12 of 68

(3) Review of and feedback on consultant team deliverables

(4) LAPD’s existing and new policies, including the March 2022 pretextual stops policy

(5) Task Force-led self-enforcing streets literature review

(6) Review of draft study findings and recommendations

3. Task Force Research Subcommittee

To increase coordination with the consultant team and provide a dedicated space for the Task

Force to share input on consultant team deliverables, members voted to create a Research

Subcommittee during the November 2022 meeting. The committee, which consisted of five

members, met five times between December 2022 and March 2023. Meeting topics were

closely aligned with previous or upcoming Task Force meeting topics and were designed to

preview consultant team deliverables for feedback from this smaller group prior to presentations

to the full Task Force.

4. Self-enforcing Infrastructure Literature Review

During the October 2022 Task Force meeting, several members called for the study to include

discussion and recommendations related to self-enforcing street design as a method of

alternative traffic enforcement. The City’s initial Task Order did not include infrastructure as a

component of the study. Members emphasized that street design techniques – including

narrower streets, wider sidewalks, enhancements for pedestrian crossings, protected bike

lanes, landscaping, etc. – can compel individuals to abide by traffic laws by using design

interventions to slow traffic.

In response, the Task Force voted in November 2022 to produce a Task Force-led literature

review for the final study. One member led the development of this study, with feedback from

the Task Force and Research Subcommittee at several touch points. The Task Force approved

the final literature review during the February 16, 2023 meeting (See Appendix E).

Page 13 of 68

IV. RESEARCH FINDINGS

The consultant team worked with the Traffic Enforcement Alternatives Advisory Task Force,

LADOT staff, and City stakeholders to develop a research approach focused on providing

comprehensive and effective solutions to traffic enforcement disparities that are responsive to

Los Angeles’ unique context. As part of the study approach, the consultant team worked with

the Task Force to define and confirm the research problem statement. The team utilized the

problem statement to build out three main research questions:

(1) What are other cities, counties, police departments, and governmental bodies doing

about traffic enforcement nationwide?

(2) What does the reported LAPD policing data show about near-recent (2019-2021) traffic

stops?

(3) How do Angelenos respond to the potential of removing traffic enforcement

responsibilities to an unarmed, civilian government unit?

The consultant team explored the research questions through a three-pronged approach which

included identifying case studies, analyzing quantitative data (e.g., data on traffic stops,

demographics, and outcomes), and examining qualitative data (i.e., community stakeholder

focus groups, expert interviews). The following section outlines the research process,

methodology, and findings.

The consultant team also conducted research and analysis regarding the legal implications of

the recommendations in this report. These findings are described at the end of this section.

A. CASE STUDY REVIEW FINDINGS

1. Purpose

The consultant team conducted a nationwide scan of publicly available literature and sources

that focused on innovative and emerging international, U.S. state, and local policies, programs,

and initiatives aimed at eliminating discriminatory and biased traffic safety and enforcement.

The purpose of this scan was to answer the research question: “What are other cities, counties,

police departments, and governmental bodies doing about traffic enforcement nationwide?” By

compiling examples of how other organizations have answered this question, the consultant

team sought to provide the City of Los Angeles with case studies that outlined the various

approaches to transitioning, reducing, or limiting traffic enforcement.

2. Methodology

The case studies focused specifically on preventative measures to limit interactions between

residents and police under the premise of traffic- or vehicle-related stops. The consultant team

categorized the identified case studies into the following tiers:

Page 14 of 68

(1) Tier 1: Government at-large has transitioned powers of police enforcement to a

Department of Transportation (DOT) or another municipal unit.

(2) Ti

er 2: Government at-large is in the process of transitioning powers of police

enforcement to DOT or another municipal unit.

(3) Ti

er 3: Government entities have made policy or protocol changes to reduce traffic

safety enforcement via other means such as banning minor traffic enforcement, non-

police alternatives, or decriminalizing minor traffic violations.

(4) Ti

er 4: Government entities are exploring either of the tiers above but have not

implemented anything to date.

(5) Ti

er 5: Non-governmental entities have examined how to decriminalize mobility through

guidelines, reports, podcasts, etc.

The tiers are organized based on the status of actions taken to mitigate traffic enforcement.

Tiers 1 and 2 include case studies where the city, state, or county has or is actively transitioning

police powers of traffic enforcement to a non-police alternative. Tiers 3 and 4 outline case

studies where a governmental entity, such as the police department, has or is actively reducing

or limiting the extent of traffic enforcement within their jurisdiction. Altogether, Tiers 1 through 4

can be considered as examples of top-down efforts to ameliorate harm in traffic enforcement.

Tier 5 includes case studies of non-governmental organizations that are calling for changes in

traffic enforcement through guides, reports, tools, etc. These case studies can be considered as

examples of formal, organized community efforts to advocate for changes in traffic enforcement

practices. It should be noted that the search included traffic enforcement of all individual

transportation mode types, including people using mobility devices, public transit, bicycling,

walking, and driving.

3. Findings

The case studies were organized into tiers based on the degree to which the city, state, county,

or other governmental agency has made efforts to reduce, limit, or transition traffic enforcement

to non-police alternatives.

Case studies in New Zealand (Tier 1) and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Tier 2) represent the

most advanced examples of harm reduction through shifts in power for traffic enforcement. Both

governmental bodies decided to use non-police alternatives to enforce certain types of traffic

laws. In New Zealand, non-moving violations and minor moving violations were enforced by the

Traffic Safety Service, a civilian governmental unit, for 30 years. While the unit has since

merged with the New Zealand Police, the case study shows that specific traffic enforcement

duties can be conducted successfully by unarmed, civilian units.

In Philadelphia, city leadership and residents voted to move towards an adaptation of the New

Zealand example where minor traffic violations are enforced by unarmed public safety “officers”

housed within the Department of Transportation. Philadelphia restructured traffic violations into

“primary” and “secondary” classifications and prohibited police from making traffic stops for

“secondary” traffic violations.

Table 1: Tiers 1 and 2 Case Studies

Tier

Location

Key Findings, Policy, Program or Funding Considerations

Page 15 of 68

1

New Zealand

Nationwide, New Zealand used a non-police governmental

agency to enforce traffic laws between 1936 and 1992. The

agency was tasked with traffic enforcement of non-moving

violations and minor moving violations. The non-police

governmental agency dissolved due to the personnel costs, not

traffic safety concerns, associated with maintaining the agency.

It is important to note that the financial constraints were a result of

staffing the non-police governmental agency with transferred

police officers and not hired civilians. Traffic enforcement remains

a responsibility of the New Zealand Police, though it should be

noted that New Zealand Police “do not normally carry guns” on

their person during traffic stops.

2

Philadelphia, PA

Under the Driving Equality Act, police are permitted to make traffic

stops for “primary” violations that compromise public safety but

stops will no longer be used for “secondary” violations, like a

damaged bumper or expired registration tags.

There are several examples of cities, states, counties, or other governmental units that have

decided (Tier 3) or are considering (Tier 4) limits, reductions, or restrictions in traffic

enforcement. A bulk of Tier 3 case studies in the U.S. have altered enforcement practices or

policies to reduce the number of potential traffic stops. In several examples, this looks like

prohibiting police from making traffic stops solely for non-moving violations – such as a broken

taillight – or decriminalizing driving with a suspended license if the reason for suspension was

solely for late or non-payment of fines and fees. In addition, other Tier 3 case studies include

governmental entities that have repealed or amended laws to decriminalize specific types of

traffic violations. By doing so, the potential for pretextual stops by police is decreased overall.

The case studies in Tier 4 represent governmental entities that have reviewed police reform

recommendations or city-appointed task forces that have provided formal recommendations for

police reforms. These examples explicitly outline recommendations to limit, reduce, or transition

traffic enforcement from police to non-police alternatives.

Table 2: Tiers 3 and 4 Case Studies

Tier

Location

Key Findings, Policy, Program or Funding Considerations

3

Berkeley, CA

The City of Berkeley passed a package of reforms in February

2021 that included prohibiting police from making traffic stops for

minor traffic infractions.

The reforms include requiring written

consent for searches, precluding police from asking about parole

or probation status in most circumstances, looking into the legality

of reviewing officers’ social media postings to fire officers who

post racist content, and implementing an “Early Intervention

System” to get biased officers off the street.

3

Oakland, CA

Oakland City Council passed the 2021-2023 Fiscal Year budget in

May 2021 with several items for investing in policing alternatives.

Page 16 of 68

The list included shifting some traffic enforcement responsibilities

to the Oakland Department of Transportation (OakDOT). The

OakDOT is reorganizing its parking division and is now

responsible for identifying and towing abandoned cars, as of April

2022. In addition, the approved budget also dedicates funds for

an audit of the Oakland Police Department (OPD), including a

goal to assess the feasibility of transitioning minor traffic

enforcement duties to civilian traffic officers. It should be noted

that OPD significantly reduced traffic stops related to minor traffic

violations by changing internal policy in 2016, which resulted in

traffic stops of Black drivers decreasing from 61% to 55% in three

years.

3

Pittsburgh, PA

The Pittsburgh City Council voted in December 2021 to prohibit

traffic stops for “secondary traffic violations,” such as broken

taillights or outdated registrations under a 60-day grace period--

meaning that a driver won't be pulled over for expired registration

unless the registration is more than 60 days out of date.

3

Seattle, WA

The Seattle Police Department updated traffic enforcement

practices based on recommendations from an equity-focused

working group. As of January 2022, Seattle Police are not allowed

to conduct traffic stops solely for minor, non-moving traffic

violations. The list of infractions that officers won't actively ticket

include:

• Vehicles with expired license tabs.

• Riders who are not wearing a bike helmet.

• Vehicles with a cracked windshield.

• Items hanging from a vehicle's rear-view mirror.

3

Portland, OR

The City of Portland, OR no longer allows police to conduct traffic

stops for non-moving violations that do not present an immediate

public safety threat, as of June 2021. Police are still allowed to

make stops for moving violations and stops related to ongoing

investigations.

3

King County, WA

Residents and visitors in the City of Seattle are no longer required

to wear a helmet while riding a bicycle. The King County Board of

Health voted in February 2022 to repeal its mandatory helmet

laws to reduce the potential for traffic stops related to the law.

3

Minneapolis, MN

The Minneapolis City Council passed a directive to city staff to

form an unarmed Traffic Safety Division housed outside of the

Police Department. Minneapolis began operating with new

policies on traffic enforcement in August 2021. Police Chief

Arradando is instructing officers not to stop drivers for minor traffic

violations. The Minneapolis City Attorney’s Office will no longer

prosecute people for driving with a suspended license, so long as

the sole reason for the suspension is failure to pay fines and fees.

Page 17 of 68

3

Lansing, MI

The City of Lansing enacted new traffic stop guidelines in July

2020 to restrict officers from stopping drivers solely for secondary,

or non-moving, traffic violations. Police would still be able to

conduct a traffic stop if it is associated with a primary traffic

violation and a public safety risk.

3

Colorado

The State of Colorado passed a law in March 2022 that allows

bicyclists to conduct an “Idaho Stop” at intersections unless

otherwise stated. An “Idaho Stop” is generally a practice where

bicyclists can treat stop-signed intersections as stop-as-yield.

3

Nevada

The State of Nevada passed bills in 2021 that end license

suspensions solely for failure to pay fines and fees, and convert

minor traffic violations, such as broken taillights, from criminal

offenses into civil offenses. The change in license suspension

rules went into effect in October 2021, and the decriminalization of

minor traffic offenses will go into effect in 2023.

3

Idaho

The State of Idaho amended state law in 2018 to shift first or

second-time driver’s license violations from criminal infractions to

civil infractions, punishable by fines. In addition, violations for

driving with a suspended license are considered civil violations for

specific minor offenses, such as the failure to pay fines.

3

Virginia

The State of Virgina amended its laws to end debt-based license

suspensions in 2020. To address pretextual stops, Virginia

passed HB 5058 and SB 5029, which prohibit law-enforcement

officers from using common traffic and pedestrian violations as a

primary offense for stopping people for things such as jaywalking

or entering a highway where the pedestrian cannot be seen, as

well as vehicles with defective equipment, dangling lights, or dark

window tint. The laws took effect on March 1, 2021.

3

Brooklyn Center,

MN

The Brooklyn Center City Council voted in May 2022 to approve a

police reform package, which includes restricting police from

making minor traffic stops for non-moving violations, unless

required by law.

3

Kansas City, MO

The Kansas City City Council repealed municipal codes in May

2021 that allowed residents to be stopped by police for jaywalking

(Sec. 70-783), not having a clean bike wheel or tires “which carry

onto or deposit in any street, highway, alley or other public place,

mud, dirt, sticky substances, litter or foreign matter of any kind”

(Sec 70-268), or for a bicycle inspection “upon reasonable cause

to believe that a bicycle is unsafe or not equipped as required by

law, or that its equipment is not in proper adjustment or repair”

(Sec. 70-706).

Tier

Location

Key Findings, Policy, Program or Funding Considerations

Page 18 of 68

4

Washington, DC

The Police Reform Commission of Washington, DC

recommended several alternative policing methods for traffic

enforcement in the District. The recommendations included

prohibiting traffic stops and repealing or revising traffic laws for

violations that are not an immediate threat to public safety;

restricting police to approved pretextual stops for violent crimes;

prohibiting safety compliance checkpoints; and transferring police

power for enforcing non-threatening traffic violations to non-police

municipal units.

4

Denver, CO

A police reform task force in Denver provided many

recommendations to minimize unnecessary police interactions

with residents, including several that specifically address traffic

enforcement. Recommendations include decriminalizing minor

traffic violations that are often used for pretextual stops,

prohibiting searches during vehicle stops for minor offenses or

traffic violations, and shifting police power in traffic enforcement to

non-police alternatives. The following recommendations call for a

fundamental shift in the way traffic stops are handled:

• Decriminalize traffic offenses often used for pretextual

stops.

• Prohibit Denver Police from conducting searches in

relation to petty offenses or traffic violations.

• Remove police officers from routine traffic stops and crash

reporting and explore non-police alternatives that

incentivize behavior change to eliminate traffic fatalities.

• Eliminate the need for traffic enforcement by auditing and

investing in the built environment to promote safe travel

behavior.

• Invest in a community-based, community-led violence

prevention strategic plan that includes, but is not limited to,

traffic stop violence and government sanctioned violence.

4

Austin, TX

The Reimagining Public Safety Task Force in Austin, TX released

a report with several recommendations, including shifting traffic

violations to non-police trained professionals, decriminalizing

traffic offenses, and disarming traffic control officers.

4

Cambridge City

The Cambridge City Council is considering alternatives to traffic

enforcement. A proposal reviewed by the City Council would shift

traffic stop duties from police to unarmed, trained city staff.

4

New York City

In March 2021, The New York City Council approved a bill (File

No. Int 2224-2021) that would move the responsibility of traffic

crash investigations to the New York Department of

Transportation. The intent is to allow officers to “focus on more

serious crimes” and shift some responsibilities from the police to

civilian municipal units. A separate bill (File No. Int 1671-2019)

within the same reform package was also approved in March

Page 19 of 68

2021. It requires a quarterly report on all vehicle stops, including

disaggregated demographic data, from NYPD.

4

Connecticut

The State of Connecticut passed a Police Accountability Bill in

2020 that prohibits police from asking for consent to search the

vehicle when conducting traffic stops. However, this does not

prevent a vehicle search altogether if the driver gives unsolicited

consent or the police acts upon probable cause. Additionally, the

bill directed the Police Transparency and Accountability Task

Force to consider whether traffic violations should be reclassified

into a primary-secondary system.

4

Los Angeles

County, CA

A motion by supervisors Hilda L. Solis and Janice Hahn requested

that the Board of Supervisors direct the Director of Public Health

to collaborate with Public Works, Sheriff’s Department, County

Counsel, California Highway Patrol, Los Angeles County

Development Authority, and the Los Angeles County Superior

Court to begin implementing the Vision Zero Action Plan

recommendations. A Vision Zero Action Plan was adopted by the

Los Angeles County Board of Directors to reduce unincorporated

roadways and traffic fatalities by 2025. Some recommendations

include:

• Immediately implement the following recommendations

included in the County’s Vision Zero Action Plan in

partnership with community stakeholders:

o B-2: Identify process and partners for establishing

a diversion program for persons cited for infractions

related to walking and bicycling.

o B-3: Identify process and partners to consider

revising the Los Angeles County Municipal Code to

allow the operation of bicycles on sidewalks.

• Identify any other recommendations included in the Vision

Zero Action Plan that should be implemented in

partnership with community stakeholders to further

decriminalize and enable the use of non-vehicular and

alternative modes of transportation in unincorporated

communities.

• Instruct the Director of Public Health, in consultation with

the Chief Executive Office and relevant County

departments, to develop cost estimates and identify

funding needs and potential opportunities to support the

implementation of these Vision Zero recommendation.

4

San Francisco

The San Francisco Police Commission passed a policy to ban

police from making nine different types of pretextual stops. The

first draft of the policy had proposed 18 types of stops, but the

final policy removed five of them and edited seven for additional

specificity. It should be noted that this policy would still allow

police to make stops for the nine enumerated reasons but in

limited circumstances.

Page 20 of 68

4

Los Angeles, CA

The Los Angeles Police Department approved a pretextual stop

policy in February 2022 which prevents officers from initiating a

stop solely for a minor traffic violation. LAPD officers are still

allowed to make pretextual stops but must do so without basing it

“on a mere hunch or on generalized characteristics such as a

person’s race, gender, age, homeless circumstance, or presence

in a high-crime location.” (

LAPD Departmental Manual, Policy

240.06)

4

Fayetteville, NC

In 2013, Police Chief Medlock of Fayetteville shifted traffic

enforcement in the department away from non-moving violations

and encouraged officers to focus on moving violations of

immediate concern to public safety. The number of investigative

stops for non-moving violations decreased dramatically for the

next four years, as did the number of Black drivers stopped and

searched. Peer-reviewed research using data from the

Fayetteville, NC case study shows that such changes in traffic

enforcement practices reduced traffic fatalities overall because

police were focused on moving traffic violations of immediate

danger to public safety, such as speeding (Fliss et al, 2020).

Finally, examples of non-governmental organizations (Tier 5) that have produced reports

directly related to reducing, limiting, or transitioning powers of traffic enforcement from police to

non-police alternatives represent calls for action across the U.S. Tier 5 examples use case

studies and evidence-based practices to support their recommendations. The audience for

these reports range from formal governing bodies to community members. While these reports

do not formally or immediately impact traffic enforcement practices, they include deeper and, in

some cases, localized recommendations. They can have a direct impact on local needs by

presenting supporting data and the lived experiences of people who are affected by inequitable

traffic enforcement.

Table 3: Tier 5 Case Studies

Tier

Location

Key Findings, Policy, Program or Funding Considerations

5

Promoting Unity,

Safety & Health in

Los Angeles (Los

Angeles)

Promoting Unity, Safety & Health in Los Angeles (PUSH LA),

works to end the LAPD’s use of pretextual stops to racially profile

low-income communities of color and immediate removal of the

LAPD’s Metro Division from South Los Angeles. Their

recommendations include ending the use of pretextual stops,

removing LAPD’s Metro Division from South LA, improving traffic

safety through urban design, equitably addressing the root causes

of traffic safety issues, holding officers accountable for

misconduct, and banning vehicle consent searches.

5

Alliance for

Community

Transit (Los

Angeles)

Various policy research, advocacy, and community organizing

efforts were undertaken by the Alliance for Community Transit -

Los Angeles (ACT-LA) member organizations, partners, and allies

to develop an informed report, Metro As A Sanctuary. This

Page 21 of 68

includes a community and healthy framework presented for Metro

to shift away from policing and create a more equitable and safe

transportation system centering on communities of color and

those with disabilities. This presents alternative crime prevention

measures and methods that do not center police enforcement.

Also, recommendations are split into multiple categories: care-

centered special tactics, stewardship, programming, support

services, public education, and job creation potential.

5

TransitCenter

(San Francisco,

Portland,

Philadelphia)

The report Safety For All by TransitCenter portrays how agencies

like BART in San Francisco, TriMet in Portland, and SEPTA in

Philadelphia are addressing safety concerns by hiring unarmed

personnel, developing high profile anti-harassment campaigns,

and better connecting riders to housing and mental health

services.

5

Kansas City, MO

BikeWalkKC in collaboration with the national Safe Routes

Partnership, co-authored the Taking on Traffic Laws: A How-To

Guide for Decriminalizing Mobility as a starting point for advocates

and communities interested in decriminalizing traffic violations

related to walking and biking. It draws upon the lessons learned

from BikeWalkKC’s experience successfully advocating for

legislation to decriminalize walking and biking in Kansas City. The

guide covers three key areas:

• The need to repeal laws leading to racialized traffic

enforcement

• How BikeWalkKC successfully advocated legislation to

decriminalize mobility in Kansas City.

• A Call to Action lays out steps advocates can take in their

own communities.

5

The Justice

Collaboratory-

Yale Law School

(New Haven, CT)

The report Principles of Procedurally Just Policing by Yale Law

School’s Justice Collaboratory explores the inequities surrounding

investigatory stops. The Supreme Court ruling in the Terry case,

which sought to promote crime prevention, approved police stops

on less than probable cause. Despite the ruling’s intent,

investigatory stops have continued to cause public distrust of

police due to a lack of transparency concerning policies and

policymaking processes.

5

Active

Transportation

Alliance (Chicago,

IL)

Active Transportation Alliance’s Fair Fares Chicagoland:

Recommendations for a More Equitable Transit System report

explores decriminalizing fare evasion arrests. Additionally, it

proposes ways to create a more equitable fare structure, including

a reduced transit fare program for low-income residents, fare

capping, and integrating transfers from the Chicago Transit

Authority (CTA), Pace Suburban Bus (Pace), and Metra

Commuter Rail (Metra).

Page 22 of 68

5

Community

Service Society

(New York City)

Community Service Society’s report The Crime of Being Short

$2.75: Policing Communities of Color at the Turnstile explores

arrests of low-income New York City residents who are unable to

pay the fare for public transit. The report focuses on the arrests

as an example of broken windows policing. The report proposes

decriminalizing fare evasion, using city resources to help low-

income riders instead of arrests, and deinstitutionalized broken

windows and enforcement quotas.

5

The Ferguson

Commission (St.

Louis, MO)

Addressing racial disparities in municipal warrants The Ferguson

Commission’s Report entails calls to action related to municipal

warrants including those that would decrease the negative

consequences of receiving a municipal warrant. These calls to

action include creating a municipal court “Bill of Rights,”

communicating rights to defendants in person, providing

defendants clear written notice of court hearing details, opening

municipal court sessions, eliminating incarceration for minor

offenses, canceling failure to appear warrants, developing new

processes to review and cancel outstanding warrants, scheduling

regular warrant reviews, and providing municipal court support

services.

5

Center for Policing

Equity- Yale

University (New

Haven, CT)

The Redesigning Public Safety: Traffic Safety report outlines five

overarching themes of recommendations to ameliorate and

address harm caused by traffic violence. These include ending

pretextual stops, investing in public health approaches to road

safety, limiting use of fines and fees, piloting alternatives to armed

enforcement, and improving data collection and transparency. The

report utilizes peer-reviewed journal articles and local examples to

support or describe each recommendation. The recommendations

are primarily focused on the issue of traffic safety, and the “harms

caused by unjust and burdensome enforcement, including the

preventable debt, justice system entanglement, and trauma that

too often flow from a single routine traffic stop.” The Center for

Policing Equity’s white paper on traffic safety is one of several

publications in the Redesigning Public Safety series of papers.

5

The Vera Institute

of Justice

(Brooklyn, NY)

The Vera Institute of Justice’s report on The Social Costs of

Policing aims to describe how police interactions, both at an

individual level and a community level. The report utilizes peer-

reviewed articles to support and detail the social costs of policing

within four main facets: (1) health, (2) education, (3) economic

well-being, and (4) civic and social engagement. By describing the

social cost of policing, the report underlines evidence for

policymakers to include when considering public safety

investments or the costs and benefits of police reform.

5

America Walks

(nationwide)

America Walk’s webinar How to Take on Harmful Jaywalking

Laws - Decriminalizing Walking for Mobility Justice includes expert

panel members working at the state and local level to

Page 23 of 68

decriminalize jaywalking. Kansas City, Virginia, and California

recently decriminalized jaywalking. The authors explore data and

lived experiences, showing that police disproportionately enforce

these laws in BIPOC communities, causing more harm than

purported safety interests.

• Practical lessons, knowledge, and tools to advocate for

and organize around removing jaywalking laws and

enforcement in your community.

• Intimate and timely strategies straight from the

leaders/advocates who have recently worked to repeal

jaywalking laws in their region and those who are in the

thick of it.

• The nuances of considering place, authentic community

engagement and how to gather and use convincing data

for your case.

5

The Center for

Popular

Democracy, Law

for Black Lives,

and Black Youth

Project 100

(nationwide)

The report Freedom to Thrive: Reimagining Safety & Security in

Our Communities examines racial disparities, policing, and

budgets in twelve jurisdictions across the country, comparing the

city and county spending priorities with those of community

organizations and their members. Research and proven best

practices show that increased spending on police does not make

them safer. However, many cities and counties rely on policing

and incarceration. Also, cities and counties continue to under-

resource more fair and effective safety initiatives.

5

Community

Resource Hub for

Safety and

Accountability

(nationwide)

Research Memo: Alternatives to Policing Community Resource

Hub for Safety and Accountability by Community Resource Hub

assesses work surrounding police abolition and alternatives to

policing, focusing on police abolitionist frameworks. This memo

provides recommendations for advocates, activists, and

organizers working on alternatives to policing as well as a list of

resources.

In sum, racially biased traffic enforcement is widely prevalent in cities, states, and counties

across the U.S. There are very few case studies that provide examples of transitioning powers

of traffic enforcement to non-police agencies. However, numerous government entities, ranging

from individual police departments to entire states, are moving forward with changes to existing

traffic regulations or traffic enforcement practices. These adjustments in how police act upon

minor traffic offenses, though limited in scale, have been shown to create a larger impact in

decreasing the number of traffic stops overall (i.e., Fayetteville, NC). Altogether, cities, states,

counties, and non-governmental entities are finding ways and making progress towards more

equitable traffic enforcement practices.

4. Next Steps

Many jurisdictions contemplating a shift in traffic enforcement practices and policies vary in size,

demographics, and physical geographic area. The consultant team sought to identify case

studies and expert interviews as a starting point for contemplating future changes in traffic

Page 24 of 68

enforcement, specifically for the City of Los Angeles. To deepen the case for the City of Los

Angeles, the consultant team conducted quantitative and qualitative analyses on traffic

enforcement using data from LAPD and with Angelenos.

The consultant team also worked with LADOT and LAPD to identify relevant case studies for

further research through expert interviews. Some case study locations were identified based on

the degree or extent of the changes in traffic enforcement, while others were identified based on

likeness or proximity to the City of Los Angeles. Three case study locations were initially

selected as case studies (See Appendix F) for further exploration, including New Zealand;

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Fayetteville, North Carolina

. Ultimately, a few other cities were

included in the expert interviews, including Berkeley, California and Oakland, California.

Additional details about the expert interviews are described in Section IV.D.

B. QUANTITATIVE DATA FINDINGS

The quantitative analysis focused on a descriptive analysis of California Racial and Identity

Profiling Act (RIPA) data. LAPD and LADOT provided additional data for the quantitative

analysis. These data are largely similar to public information from the RIPA data portal but also

include location information.

1. Purpose

Racial differences in policing and traffic stops are well documented.

36,37,38,39

The Traffic

Enforcement Study problem statement describes how police traffic enforcement

disproportionately affects people of color and the need to address disparities in traffic safety.

Documenting trends in Los Angeles was a critical grounding component of this study, even with

this background of empirical evidence from national trends. Therefore, the consultant team

analyzed the recent trends, spatial patterns, and racial/ethnic dimensions of LAPD traffic stops

as a critical component of the Traffic Enforcement Study.

This analysis answers the following questions from the data:

36

Pierson, E., Simoiu, C., Overgoor, J., Corbett-Davies, S., Jenson, D., Shoemaker, A., Ramachandran,

V., Barghouty, P., Phillips, C., Shroff, R., & Goel, S. (2020). A large-scale analysis of racial

disparities in police stops across the United States. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(7), Article 7.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0858-1

37

Roach, K., Baumgartner, F. R., Christiani, L., Epp, D. A., & Shoub, K. (2022). At the intersection: Race,

gender, and discretion in police traffic stop outcomes. Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics, 7(2),

239–261. https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2020.35

38

Cai, W., Gaebler, J., Kaashoek, J., Pinals, L., Madden, S., & Goel, S. (2022). Measuring racial and

ethnic disparities in traffic enforcement with large-scale telematics data. PNAS Nexus, 1(4),

pgac144. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac144

39

Knowles, J., Persico, N., & Todd, P. (2001). Racial Bias in Motor Vehicle Searches: Theory and

Evidence. Journal of Political Economy, 109(1), 203–229. https://doi.org/10.1086/318603

Page 25 of 68

(1) Who: demographic patterns of stops, focusing primarily on racial and ethnic

composition;

(2) Why: reasons for stops;

(3) What: actions occurring during the stops and stop results, focusing mainly on citation

rates; and

(4) Where: geographic spatial patterns.

In addition, the problem statement details how low-income communities of color are

disproportionately affected by traffic violence and how this work is connected to the Vision Zero

Initiative to end traffic fatalities. The statement demonstrates concern about the role of police

involvement in meeting traffic safety goals. Therefore, the consultant team analyzed traffic

enforcement patterns for speeding because increased speeds increase the risk of severe injury

or fatalities.

Overall, this analysis complements and bridges findings from the qualitative data collection

described in the following section of this report and proposes recommendations that connect

experiences shared in the focus groups with empirical data about LAPD police stops.

2. Methodology

This analysis relies primarily on stop data collected and maintained by LAPD according to the

California Racial and Identity Profiling Act (RIPA). RIPA was enacted in 2015 to create a

standard set of data that police departments in California must record and regularly provide to

the Department of Justice. LAPD was included in the first wave of police departments required

to submit data and therefore began collecting and reporting standardized data in mid-2018.

The consultant team made an initial data request to LAPD in mid-2022 for the last three years of

RIPA data (2019 – 2021) (See Appendix G for data fields and descriptions). Nearly all this

analysis covers that period. The team also requested and included the number of stops for 2022

and some smaller sub-analyses using 2022 data.

This analysis includes specific components from similar studies of police stops by LAPD and

other police departments. Relevant reference studies include:

(1) "An Analysis of the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department's Traffic Stop Practices"

(2018) Alex Chohlas-Wood, Sharad Goel, Amy Shoemarker, Ravi Shroff. Stanford

Computational Policy Lab

(2) "Annual Report 2022" (2022) Racial and Identity Profiling Advisory Board RIPA

(3) "Racial Disparities in Traffic Stops" (2022) Magnus Lofstrom, Joseph Hayes, Brandon

Martin, and Deepak Premjumar. Public Policy Institute of California

(4) "Reimagining Traffic Safety and Bold Political Leadership in Los Angeles" (2021) PUSH

LA

Page 26 of 68

(5) "Review of stops conducted by the Los Angeles Police Department in 2019" (2019)

Office of the Inspector General, Los Angeles Police Commission

a. Data Comparisons

The consultant team compared the trends within these RIPA data to demographics within the

city of Los Angeles using data from the 5-year American Community Survey (ACS) (2017 -

2021). However, these datasets differ in the racial/ethnic and gender categories they use.

Further, the racial/ethnic data from the RIPA dataset is based on officer perception (who can

record more than one racial identity), while the ACS data uses self-reported racial/ethnic

information. The following table outlines these differences and the transformations required to

appropriately match the data between the two datasets.

Table 4: Comparison race/ethnicity datasets

RIPA Data

ACS Data

Report approach

Asian

Asian

Asian

Black/African American

Black/African American

Black/African American

Hispanic/Latino

Hispanic/Latino collected as

question on ethnicity,

separate from race

Anyone who reports being of

Hispanic/Latino ethnicity,

regardless of race, is

included as Hispanic/Latino

Middle Eastern or South

Asian

Not included

Middle Eastern and South

Asian included in Other

Native American

Native American

Pacific Islander

Pacific Islander

White

White

White

Not included

Other

Grouped within other

Two or more races

Grouped within other

The consultant team used the LAPD reporting district boundary for the spatial analysis. While

the RIPA dataset includes a more specific geographic location, the data often needed to be

completed with street suffix (e.g., avenue, street, boulevard etc.) or direction. This would require

a great deal of manual cleaning to ensure correct spatial placement. Therefore, the team used

the reporting district where the stop took place as an alternative. LAPD reporting districts are

small areas (1135 total)

40

with an average size of 0.5 square miles. The team aggregated these

reporting districts to the neighborhood level using the neighborhood boundaries established in

the “Mapping L.A.” project from the Los Angeles Times. In cases where the reporting district and

neighborhood boundaries did not align exactly, the number of stops were proportionately

allocated to the neighborhood boundaries.

b. Task Force Member Input

The consultant team regularly presented this analysis to the Task Force to allow members and

other project stakeholders (e.g., LAPD) to provide feedback. The team added the following

specific component to this analysis at Task Force members’ requests:

(1) Analysis of recent LAPD policy change: In 2022, LAPD instituted a directive to

change enforcement of pretextual stops. The consultant team conducted a sub-analysis

comparing a six-month timeframe in 2021 to the same six-month timeframe in 2022 to

40

For reference, there are approximately 1324 census tracts in the City of Los Angeles.

Page 27 of 68

analyze the effect of this change on stops both in terms of the categories of traffic

violation stops (% change in moving vs. equipment vs. non-moving) and related patterns

by race/ethnicity.

3. Findings

Traffic stops have declined year-over-year since 2019, from nearly 713,000 annually in 2019 to

331,000 in 2022 (Table 5 & Table 6). Most stops (74%) are for traffic violations, and speeding is

the most common traffic violation type (16% of all traffic violation stops) (Table 7). Black drivers

are disproportionately stopped (27% of all traffic stops; 26% of traffic violation stop, 8% of city

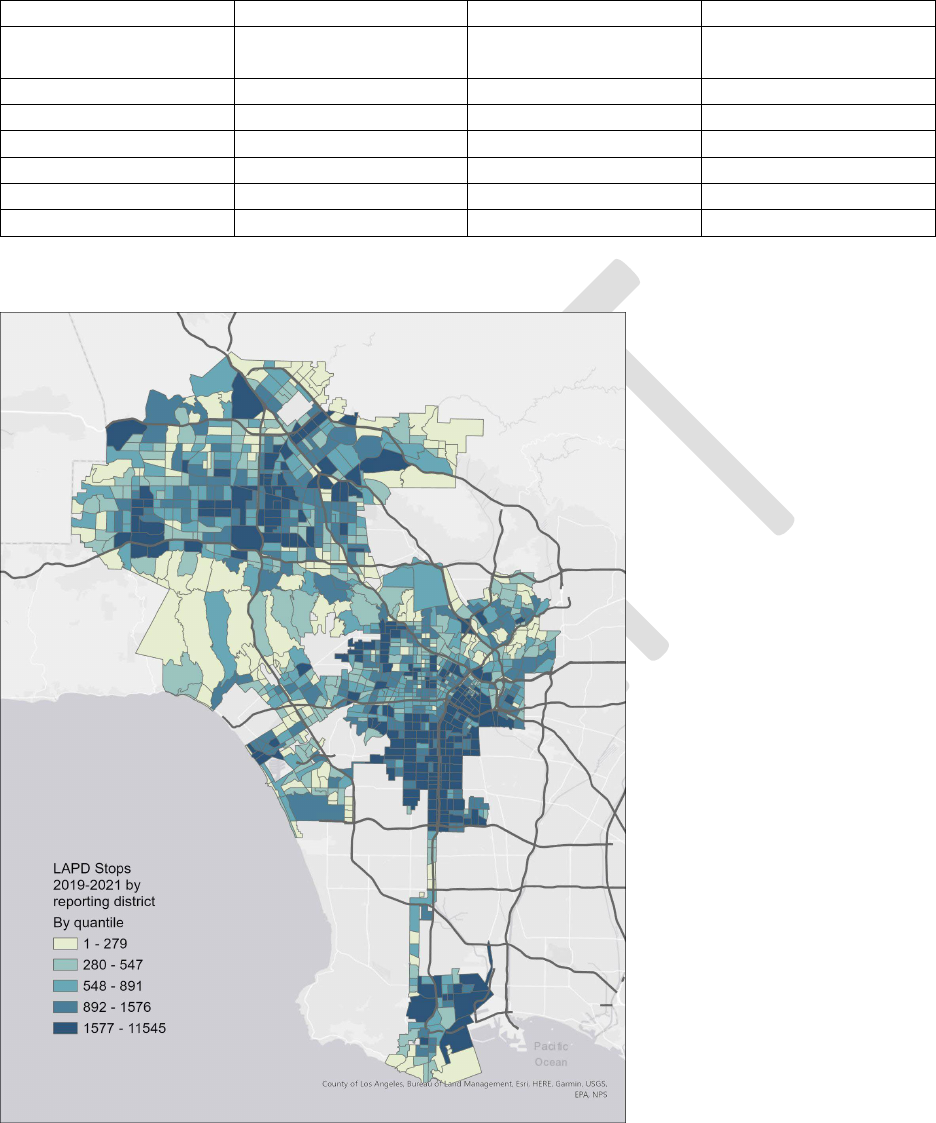

population) (Table 8). The rate of stops per 100,000 people differs by neighborhood (Figure 1).

More stops per capita occur in Greater South Los Angeles and neighborhoods south of

Hollywood (Figure 2).

Within traffic violations specifically, most traffic violation stops happen for moving violations

(45%), with equipment violations next most common (31%), and non-moving the least common

(24%) (Table 10 & Table 11). Black drivers are stopped at three times the city average in traffic-

violation-related stops, a similar rate to police stops overall (Table 12 & Table 13).

The early results from the recent LAPD policy change directing officers not to make stops for

minor traffic violations (pretextual stop change) has changed the percent of stops by traffic

violation categories. In the six-months post-change in 2022, the percentage of stops for moving

violations rose from 52% (2021) to 71% (2022) (Table 14 & Table 15). The percentage of

equipment stops dropped from 29% (2021) to 20% (2022), and non-moving violation related

stops dropped from 20% (2021) to 9% (2022). The percentage of traffic violation stops for

speeding increased from 18-21% (2021 vs. 2022). This policy change has resulted in lower

percentages of Black drivers being stopped dropping from 26% of stops to 21% of stops (Table

16).

During most traffic violation stops, no actions (searching, use of force, detention, removal from

vehicle, etc.) are taken (73%) (Table 17). Black drivers are more likely to be subject to more

actions (13% one action, 23% two to five actions), including use of force (Table 18). Use of

force only occurs in a small percentage of traffic violation stops (0.4%), with Black drivers

receiving a disproportionate use of force (30% of use of force stops and 33% firearm pointed at

person, with Black residents making up 8% of the city’s population) (Table 19 & Table 20).

Most stops end in no result (citation, warning, etc.), and the percent of stops ending in no result

is relatively consistent across racial/ethnic groups (Table 21 & Table 22). Further, a minority of

traffic violations result in a citation (31%). Moving violations are more likely to result in a citation

(46% of stops); 14% of equipment violations and 23% of non-moving violations result in a

citation (Table 23).

The consultant team’s analysis for speeding and Vision Zero found that Black drivers are

stopped less for speeding than all traffic stops but still higher relative to the Black population

(Table 24 & Table 25). Most stops for speeding do not result in a citation (58%) or a warning

(11%) (Table 26). The racial trends in speeding stops that result in a citation are closer to racial

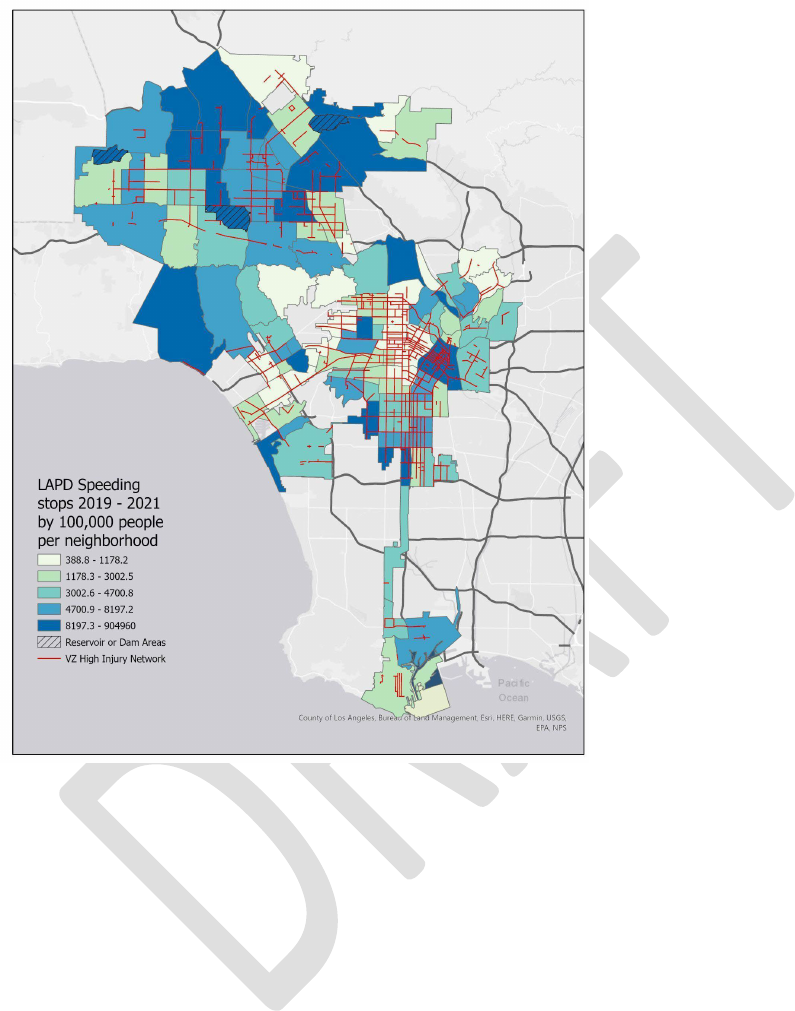

parity than other components (Table 27). Speeding stops are more likely to occur in

neighborhoods in the San Fernando Valley (Porter Ranch, Northridge, Lake Balboa, Sun Valley,

and others), in Downtown Los Angeles, Pacific Palisades, and Leimert Park (Figure 3, Figure 4,

& Figure 5). Finally, there is a weak relationship (r=.19) between the miles of streets on the

high-injury network and the number of stops for speeding by neighborhood (Figure 6). The

Page 28 of 68

relationship is near eliminated (r=.0012) when stops for speeding are normalized by

neighborhood population (Figure 7).

All the data tables and maps for this summary and more extensive tables and figures are

presented below.

a. Detailed Tables & Figures

(1) All traffic stops (2019-2021)