UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones

December 2018

Examining Environmental Hazards in Rental Homes and Examining Environmental Hazards in Rental Homes and

Habitability Laws in Clark County, Nevada Habitability Laws in Clark County, Nevada

Jorge Luis Bertran

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations

Part of the Environmental Health Commons, Environmental Health and Protection Commons, and the

Public Health Commons

Repository Citation Repository Citation

Bertran, Jorge Luis, "Examining Environmental Hazards in Rental Homes and Habitability Laws in Clark

County, Nevada" (2018).

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones

. 3401.

http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/14279034

This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV

with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the

copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from

the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/

or on the work itself.

This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by

an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact

digitalscholarship@unlv.edu.

EXAMINING ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS IN RENTAL HOMES AND HABITABILITY

LAWS IN CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA

By

Jorge Luis Bertran

Bachelor of Arts – Psychology

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

2005

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the

Master of Public Health

Department of Environmental and Occupational Health

School of Community Health Sciences

Division of Health Sciences

The Graduate College

University of Nevada, Las Vegas

December 2018

Copyright 2019 by Jorge Luis Bertran

All Rights Reserved

ii

Thesis Approval

The Graduate College

The University of Nevada, Las Vegas

November 5, 2018

This thesis prepared by

Jorge Luis Bertran

entitled

Examining Environmental Hazards in Rental Homes and Habitability Laws in Clark

County, Nevada

is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Public Health

Department of Environmental and Occupational Health

Courtney Coughenour, Ph.D. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D.

Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Interim Dean

Shawn Gerstenberger, Ph.D.

Examination Committee Member

Max Gakh, J.D., M.P.H.

Examination Committee Member

Chad Cross, Ph.D

Examination Committee Member

Dak Kopec, Ph.D.

Graduate College Faculty Representative

iii

Abstract

It is well established that home conditions are linked to the health outcomes of occupants. There

are over 880,000 housing units in Clark County, Nevada; nearly half of those are renter-occupied

units (ROUs). Currently, there is limited research on the characteristics of environmental

hazards found in Clark County ROUs and the strength of habitability statutes created to protect

tenants from substandard housing. Understanding how renters in Clark County are affected by

environmental hazards in ROUs and the processes by which landlords and tenants resolve

grievances related to those hazards would benefit public health. It would enhance the ability to

quickly identify which ROUs are at most risk for hazards and allow public health professionals

to better plan and implement strategies intended to mitigate or prevent negative health outcomes

created by those hazards. This study examined data from the Clark County Landlord and Tenant

Hotline Study to answer the following questions: (1) Is there a relationship between the age of

ROUs and the types of environmental hazards found in them? (2) Is there is a statistically

significant difference in the proportions of hazards remediated by tenants who received a site

inspection from the SNHD or sought legal advice in addition to sending a complaint letter to

their landlord? (3) Do the age of an ROU, the number of complaints made by each tenant, or

complaint category influence the likelihood of remediation? An ANOVA revealed that the

average age of ROU’s was statistically significantly different between hazard categories, F(4,

445) = 5.11, p = 0.002. A Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed mean differences were

statistically significant between essential services (= 35.27, SD = 16.59) and mold ( = 27.64,

SD = 12.77; p < 0.05) and essential services and other (= 23.25, SD = 11.62; p < 0.05). A chi-

square test of homogeneity suggested that there was no statistically significant difference in the

proportions of hazards remediated by tenants who pursued different levels of intervention, X

2

=

iv

1.11, p = 0.292. A binary logistic regression revealed that for each 1-year increase in ROU age,

the likelihood of remediation was decreased by 2.5%. For tenants with one complaint, the odds

of remediation were 1.75 times (95% CI =1.06 - 2.89) that of tenants with multiple complaints.

For complaints categorized as essential, the odds of remediation were 4.15 times (95% CI =1.36

- 12.7) that of complaints categorized as non-essential. The results suggest that the mean age of

ROU’s with essential service complaints is higher than ROU’s with complaints categorized as

mold or other. Furthermore, a tenant’s probability of getting hazards remediated was not

significantly increased if they received a site inspection or sought legal advice in addition to

sending their landlord a letter. The study suggests that tenants were less likely to get their hazard

remediated by their landlords if they had multiple complaints, lived in an older home, or had a

non-essential complaint. The results of this study can be used to enhance our abilities to quickly

identify which ROUs in Clark County are most at risk for hazards and identify the factors that

influence the likelihood of remediation.

Committee In Charge:

Courtney Coughenour, Ph.D., Advisory Committee Chair

Shawn Gerstenberger, Ph.D., Advisory Committee Member

Max Gakh, JD, MPH, Advisory Committee Member

Chad Cross, Ph.D., PStat(R), Advisory Committee Member

Dak Kopec, Ph.D., MS.Arch., MCHES, Hon. FASID, Graduate College Representative

v

Table of Contents

Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii

Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1

Chapter 2: Background ................................................................................................................... 4

The Relationship Between Housing and Health ......................................................................... 4

Disease Vectors and Pests ....................................................................................................... 4

Indoor Air Pollutants............................................................................................................... 6

Toxic Substances .................................................................................................................... 8

Housing Structure and Protection from Environmental Elements ........................................ 10

Plumbing and Waste Management ....................................................................................... 11

Electrical ............................................................................................................................... 12

Heating, Cooling, and Ventilation ........................................................................................ 13

Landlord and Tenant Habitability Law ..................................................................................... 14

Implied Warranty of Habitability.......................................................................................... 15

Uniform Residential Landlord and Tenant Act .................................................................... 16

Nevada Habitability Law ...................................................................................................... 19

Clark County Landlord and Tenant Hotline Study ................................................................... 21

Basic Services Procedures .................................................................................................... 22

Research Activities Procedures............................................................................................. 23

Chapter 3: Methods ....................................................................................................................... 26

vi

Study Design ............................................................................................................................. 26

Inclusion Criteria .................................................................................................................. 26

Hypotheses and Methods ...................................................................................................... 27

IRB and Data Management ................................................................................................... 29

Chapter 4: Results ......................................................................................................................... 30

Descriptive Statistics ............................................................................................................. 30

Hypotheses Analysis ............................................................................................................. 30

Chapter 5: Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations ....................................................... 34

Discussion ............................................................................................................................. 34

Limitations ............................................................................................................................ 36

Conclusions and Recommendations ......................................................................................... 37

Appendix A: Sample Essential Complaint Letter Template ......................................................... 43

Appendix B: Example Non-Essential Complaint Letter Template............................................... 45

Appendix C: CCLTHS Follow-Up Survey ................................................................................... 47

Appendix D: IRB Approval .......................................................................................................... 52

References ..................................................................................................................................... 53

Curriculum Vitae .......................................................................................................................... 62

1

Chapter 1: Introduction

Clark County, located in Southern Nevada, is the 14th largest county in the United States

(Clark County, n.d.), encompasses over 7,800 square miles and has an estimated population of

over 2 million people (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). Of the over 880,000 housing units in Clark

County, Nevada; nearly half are renter-occupied units (ROUs) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017).

Currently, there is limited research on the characteristics of environmental hazards found in these

ROUs and the process by which landlords and tenants resolve grievances related to those

hazards.

Understanding how renters in Clark County are affected by environmental hazards in

ROUs and the laws created to ensure habitability of those ROUs would benefit public health

because research has linked the condition of housing to the health of the occupants. Many

environmental hazards in the home can lead to various injuries, diseases, and death (CDC &

HUD, 2006; Coyle et al., 2016). The purpose of this study is to fill gaps in knowledge that may

hinder the ability to quickly identify which ROUs are at highest risk for hazards and allow public

health professionals to better plan and implement strategies intended to mitigate or prevent

negative health outcomes created by those hazards. This is significant because the more efficient

we are at identifying these ROUs, the earlier the intervention can be applied. It is important to

population health and those most vulnerable, as they are the most likely to live in homes that

contain environmental hazards.

Laws ensuring habitability of ROUs in Nevada are outlined in Chapter 118A of the

Nevada Revised Statutes. These statutes adopted elements found in the Uniformed Residential

Landlord and Tenant Act of 1972 (URLTA) in 1977 and the Revised Uniformed Landlord and

Tenant Act (RURLTA) (NRS 118A.; Wills II et al., 2017). Although almost identical to these

2

model statutes, there is little research on the effectiveness the statutes have on ensuring

habitability. Renters can inadvertently find themselves in a precarious situation when seeking

remediation of an environmental hazard in their homes because some landlords are either

unaware of their responsibilities outlined in the statutes or take advantage of their renter’s

ignorance of the law or their difficulty in seeking its enforcement. This study can help better

understand the variables that influence the effectiveness of the laws created to protect tenants

from substandard housing and what steps a tenant can make to increase the likelihood of getting

a hazard remediated by their landlord.

The goals of this study were to (1) examine if the age of ROUs can be used to identify

hazards and (2) identify the factors that influence the likelihood of remediation. More

specifically, this study sought to answer the following research questions:

(1) Is there a relationship between the age of ROUs and the types of environmental

hazards found in them?

(2) Is there is a statistically significant difference in the proportions of hazards

remediated by tenants who pursued different levels of intervention (i.e., receiving a

site inspection from the SNHD vs. seeking legal advice after sending a complaint

letter to the landlord)?

(3) Does the age of a home, the number of complaints made by each tenant, or complaint

category influence the likelihood of remediation?

This study utilized data from the Clark County Landlord Tenant Hotline Study

(CCLTHS) to answer these questions. The CCLTHS is a UNLV and Southern Nevada Health

District (SNHD) collaboration that collects information regarding the conditions of ROUs in

3

Clark County and assists landlords and tenants with grievances regarding hazards found in

ROUs.

4

Chapter 2: Background

The Relationship Between Housing and Health

Shelter is regarded as one of our basic needs. It should be a place of refuge and safety,

but inherent dangers found in our homes can pose serious threats to the physical and

psychological well-being of an individual (CDC & HUD, 2006). An abundance of research has

shown a link between elements in the home and the health of its occupants (Coyle et al., 2016;

Gielen et al., 2012; Jacobs, 2011; Krieger & Higgins, 2002; Weitzman et al., 2013; Wu, Jacobs,

Mitchell, Miller, & Karol, 2007). This should be no surprise, considering that we spend close to

90% of our time indoors (CDC & HUD, 2006).

The CDC’s Healthy Housing Reference Manual (2006) identifies the following subjects

as important in identifying and addressing hazards in the home: (1) disease vectors and pests, (2)

indoor air pollutants and toxic materials, (3) housing structure, (4) environmental barriers, (5)

water supply and quality, (6) plumbing, (7) waste management, (8) electricity, and (9) heating,

ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC). Although each of these categories are individually

important, it is equally important to look at them collectively as an interdependent system.

Deficiencies in one area can exacerbate dangers in other areas. Examples of the dangers

associated with housing hazards include injuries, cardiovascular and neurological disorders, and

death (CDC & HUD, 2006). The common solution to preventing hazards is to be proactive and

continually assess, upkeep, and maintain all components in the focus areas identified by the CDC

and HUD (CDC & HUD, 2006).

Disease Vectors and Pests

An abundance of research has linked negative health outcomes with the presence of pests,

such as cockroaches or rodents (Ahluwalia & Matsui, 2018; Grant et al., 2017; Nasirian, 2017;

5

Olmedo et al., 2011; Phipatanakul et al., 2017). Household pests contain allergens that are

known to induce asthma and act as vectors for disease (Portnoy et al., 2013). Implementing a

pest management plan and proper upkeep of the home can significantly reduce or eliminate

exposure to pests (Nasirian, 2017; Rabito, Carlson, He, Werthmann, & Schal, 2017).

Cockroaches and rodents, the most pervasive of household pests, have intrinsic

characteristics that allow them to infest and proliferate in homes regardless of the age or

condition of the home and the socioeconomic status of its occupants (Portnoy et al., 2013).

Cockroaches are omnivorous foragers that can withstand long periods without food and prefer

tight, dark places that allow them to thrive undetected (Portnoy et al., 2013) Cockroach

allergens, which are known causative agents of asthma, can be found in nearly 90% of inner-city

homes (Do, Zhao, & Gao, 2016), and, compared to exposure to other common household

allergens from dust mites and pets, they have a larger influence on the severity and morbidity of

asthma (Pomés, Mueller, Randall, Chapman, & Arruda, 2017). Asthma is a serious problem,

particularly among children. Sullivan et al., (2017) state that over 7 million children are

diagnosed with asthma each year. Furthermore, the direct cost of childhood asthma to

Americans reach an annual total of $1 billion (Sullivan et al., 2017). Rodents have allergens that

can exacerbate asthmatic symptoms and are notorious carriers of disease (CDC & HUD, 2006;

Kass et al., 2009). Additionally, rodents can cause structural damage to homes which can further

exacerbate risks and negative health outcomes (CDC & HUD, 2006, Kass et al., 2009). Rodents

are known to chew through building materials to gain access to various parts of the home and

increase the risk of electrical fires by chewing through wires (CDC & HUD, 2006).

The most effective approach to combat pests is implementing an integrated pest

management program (IPM) (Portnoy et al., 2013; Weitzman et al., 2013). IPM utilizes

6

proactive measures that identify and eliminate ingress points, eliminate sources of food and

water, utilize traps, and use pesticides with low toxicity, if necessary (Weitzman et al., 2013).

According to Weitzman et al. (2013), many studies have shown that implementing IPM

strategies are effective in reducing cockroach allergens and could reduce allergens from other

pests also.

Indoor Air Pollutants

Repeated exposure to indoor air pollutants have been associated with various

cardiovascular diseases and other chronic conditions such as asthma ( CDC & HUD, 2006;

Mitchell et al., 2007). Pollutants that influence indoor air quality can be categorized as either

biological agents or chemical agents (CDC & HUD, 2006; Mitchell et al., 2007). Examples of

biological pollutants include pet dander, dust mites, bacteria, and molds (CDC & HUD, 2006;

Mitchell et al., 2007). Examples of chemical pollutants include volatile organic compounds

(VOCs), environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), and pesticides (CDC & HUD, 2006).

Dogs and cats are ubiquitous household pets that can be found in about half of all

households and are the source of allergies to 12% of the general population and between 25%-

65% of children with chronic asthma (Ahluwalia & Matsui, 2018). Another biological agent that

is found in almost every home and is known to exacerbate asthma is the household dust mite

(CDC & HUD, 2006). These microscopic creatures can be found by the hundreds of thousands

in nearly 85% of beds in US homes, where they thrive on the dead skin flakes of humans

(Álvarez-Chávez et al., 2016; Arbes et al., 2003; CDC & USDHUD, 2006; Salo et al., 2008). A

study by Alvarez-Chavez et al. (2016), found that households that were visually assessed to have

household dust had a statistically significant association with child occupants who were sensitive

7

to dust mites; therefore relating the cleanliness of the home as the most significant factor

associated with sensitized children.

Certain fungal species are known to induce allergic reactions in some individuals

(Borchers et al., 2017; Singh, 2005; CDC & HUD, 2006). These reactions include rhinitis,

asthma, and eye and throat irritation (Singh, 2005). Fungi found in households are more

commonly referred by colloquial, non-technical terms such as mold, toxic mold, black mold,

mildew, etc. These general terms describe a diverse kingdom with over 1 million species

(Borchers et al., 2017; Singh, 2005). In spite of the many negative misconceptions of molds,

only a few species are known to be pathogenic or toxic (Singh, 2005).

There are numerous chemical agents that affect indoor air quality as well. Products such

as air fresheners, paints, cleansers, pesticides, and waxes that release organic chemicals that

vaporize into gasses are known as VOCs (CDC & HUD, 2006). VOCs can lead to negative

health effects such as eye and nose irritation, central nervous system damage, liver damage, and

are suspected to be carcinogenic (Mitchell et al., 2007). Although exposure to VOCs is not

exclusive to inside the household, concentrations of these compounds can be higher in the indoor

microenvironment (CDC & HUD, 2006).

The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) Cancer Institute defines ETS as smoke that is

emitted from a tobacco product or exhaled by a smoker (NIH, n.d.). The CDC states that ETS

contains over 7,000 chemicals, 70 of which are known carcinogens (CDC, 2017). Furthermore,

repeated exposures to ETS can decrease the efficiency of the lungs, which can exacerbate and

increase the number of asthmatic episodes (Jacobs, Kelly, & Sobolewski, 2007; Makadia, Roper,

Andrews, & Tingen, 2017). Additionally, a less talked about consequence of ETS, third-hand

smoke, can have lingering effects in homes of non-smokers (Weitzman et al., 2013). Third-hand

8

smoke refers to residual chemicals from secondhand smoke that have deposited on surfaces it has

come in contact with (Jacob et al., 2017; Weitzman et al., 2013). These chemicals have the

ability to embed and persist in multiple household surfaces, later reacting to atmospheric gasses,

and producing and releasing byproducts that are detrimental to the health of those in the

household (Jacob et al., 2017; Weitzman et al., 2013).

Toxic Substances

Toxic substances can be found in the building material of household components such as

paint, insulation, plumbing, and siding (CDC & HUD, 2006). Lead and asbestos are examples of

toxic materials that were commonly found in households but have since been banned (CDC &

HUD, 2006). These materials were originally chosen because of their favorable intrinsic

qualities but years of research have determined direct links to negative and sometimes

irreversible health outcomes such as brain damage and lung cancers. Consequently, regulations

have been created to prohibit the use of these products in new homes and outline appropriate

means of remediation or abatement (CDC & HUD, 20016; Jacobs, Kelly, & Sobolewski, 2007).

This is a significant public health issue, as populations that are overburdened by negative and

environmental health conditions are more likely to live in older homes and be exposed to lead

(Jones et al., 2009).

Lead is an element that was popular in paints because of its durability (CDC & HUD,

2006). Although its use in consumer paint has been banned since 1978, leaded paint can still be

found today in many homes built pre-1978. According the American Community Survey (ACS)

over half of the US housing stock was built before 1980 (U.S. CensusBureau, 2016). In Nevada,

approximately a quarter of the housing stock was built before 1980 (US Census Bureau, 2016).

9

The most common routes of exposure are through the ingestion of lead paint chips or

inhalation of lead dust (Jacobs et al., 2007; Roberts, Allen, Ligon, & Reigart, 2013). Lead can

cause permanent neurological and gastrointestinal damage and bioaccumulate in bones and teeth

(Jacobs et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2013). Children are most susceptible because of their

likelihood of eating paint chips. Once lead has been ingested or inhaled by a child, its ability to

pass through the blood brain barrier and children’s gastrointestinal tracts makes them absorb lead

more readily compared to adults (Jacobs et al., 2007; Sanders, Liu, Buchner, & Tchounwou,

2009). Once lead has passed the blood-barrier, it induces damage to multiple parts of the brain

including the cerebellum, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus (Sanders et al., 2009).

Consequently, children can suffer from behavior problems, reduced IQ, neuropathy, liver

damage, and nausea (Sanders et al., 2009).

Exposure to asbestos is also known for its lifelong, irreversible effects. It is a mineral

fiber that was incorporated in many household components since the 1800’s because of its

durable and heat resistant qualities (Lemen & Landrigan, 2017). These characteristics made it a

preferred substance in thermal insulation, flooring, and roofing (Lemen & Landrigan, 2017). As

early as the 1920’s, researchers were witnessing temporal and causal relationships between

asbestos exposure and lung diseases (Kratzke & Kratzke, 2018).

Asbestos, a proven carcinogen, accounts for approximately 12,000 – 15,000 deaths each

year in the U.S. (Lemen & Landrigan, 2017). Lung cancers, mesothelioma, and debilitating

non-malignant lung diseases such as asbestosis, are caused by the inhalation of asbestos fibers

(CDC & HUD, 2006). In the case of asbestosis, inhaled asbestos fibers lodge into the cavities of

the lungs and permanently scar them, which leads to a decrease in lung capacity and a high

association with mesothelioma and lung cancers (Kratzke & Kratzke, 2018). Mesothelioma is a

10

pervasive cancer of the visceral and parietal surfaces of the chest or peritoneal surface of the

abdomen (Kratzke & Kratzke, 2018; Sekido, 2013). According to Lemen & Landrigan (2017),

the only route to decrease the amount of disease and deaths related to asbestos is to prohibit all

uses of asbestos because there is no safe level exposure. Through the Toxic Substances Control

Act, Clean Air Act, and Consumer Product Safety Act, many asbestos uses and product

manufacturing, importation, processing, and distribution in commerce were banned in the U.S.

(EPA, n.d.)

Housing Structure and Protection from Environmental Elements

Nothing exemplifies the importance of the interdependent relationship of the many

systems within a house than its structural elements. They provide protection from the external

environment, regulate the internal environment of the house, and provide structural support to

other housing systems such as plumbing and electricity. These elements include a home’s

foundation, vapor barriers, framing components, exterior and interior walls, and roofing

components (CDC & HUD, 2006). The roofing components provide protection from outside

elements and facilitate the exchange of indoor and outdoor air. Vapor barriers provide another

level of protection by preventing the ingress of moisture and harmful gasses into the home. The

framing components and interior and exterior walls house the plumbing, electrical, and HVAC

systems.

Due to the interdependent relationship that the structural components have with other

elements of the home, a fault in one area can pose a systematic threat to the entire home. The

threat of moisture entering the home because of compromised, missing, or badly constructed

structural elements demonstrates this. One of the purposes of a home’s structural components is

to prevent the ingress of moisture into the home or to prevent the accumulation of it by providing

11

a path for it to escape (CDC & HUD, 2006). When either of these criteria are not met, this can

create damp conditions that are conducive for pathogen growth and poor air quality, provide

favorable conditions for pests, and threaten the structural integrity of the home by causing the

deterioration of framing and wall components (CDC & HUD, 2006; Weitzman et al., 2013).

Plumbing and Waste Management

A home’s plumbing system is imperative to provide a clean, reliable supply of potable

water and means of wastewater removal. When the plumbing system is poorly constructed,

and/or not maintained, problems can cause components of the system to break down and

interrupt water or sewage service (CDC & HUD, 2006). Consequently, this can increase the

likelihood of water contamination, cause structural damage, foster the growth or spread of

pathogens, cause personal injury, and limit access to drinking water according the World Health

Organization (WHO) and the World Plumbing Council (WPC) (WHO & WPC, 2006).

Inconsistent or interrupted potable and waste water services can potentially lead to health

risks such as increasing exposure to untreated wastewater, eliminating the ability to wash your

hands, and limiting access to drinking water (WHO & WPC, 2006). Interrupted or inconsistent

sewage service can increase exposure to waste water which contains many harmful pathogens

such as E. coli and Giardia (CDC & WHO, 2006; WHO & WPC, 2006). Further complicating

the issue is the inability to wash and sanitize your hands (WHO & WPC, 2006). This eliminates

the first and most impactful step towards preventing the spread of infectious agents, according to

the CDC (2015). Inconsistent or interrupted water service could reduce access to drinking water

that is an essential element for the proper function of multiple body systems. Furthermore,

finding alternative sources of water could place an additional financial burden to poorer families.

12

Broken plumbing components can lead to injuries, structural damage, and the growth of

pathogens (CDC & HUD, 2006; J. O. Falkinham, Hilborn, Arduino, Pruden, & Edwards, 2015;

J. Falkinham, Pruden, & Edwards, 2015; WHO & WPC, 2006). A major contributor to both

personal injuries and the spread of pathogens is improper water temperature (J. O. Falkinham et

al., 2015; J. Falkinham et al., 2015; WHO & WPC, 2006). This is the result of water heaters that

are either not set to a recommended temperature or unable to hold consistent temperatures.

Consequently, low water temperatures can create favorable conditions for opportunistic premise

plumbing pathogens such as Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium avium, and Pseudomonas

aeruginosa (J. O. Falkinham et al., 2015; J. Falkinham et al., 2015; WHO & WPC, 2006).

Conversely, high water temperatures can scald the skin, especially in children and the elderly

(Jacobs et al., 2007; WHO & WPC, 2006).

Broken plumbing components can also lead to leaks of both potable and wastewater. An

accumulation of moisture in various structural components of the house can foster an

environment for fungi growth and is a water source for pests (CDC & HUD, 2006; Jacobs,

2011). Additionally, leaking pipes can cause structural damage by cracking paint and causing

wood and sheathing to rot. Broken wastewater pipes further complicate the problem by

increasing the potential of being exposed to harmful pathogens (CDC & HUD, 2006;WHO &

WPC, 2006).

Electrical

Potential hazards that are capable of property damage, injury, and death lie behind the

outlets that power our connected world. Nationally, there was an average of over 45,000 fires

per year between 2010 and 2014 that were related to electrical failures or malfunctions (Campell,

13

2017). These fires accounted for over 400 deaths and nearly $1.5 billion in property damage

(Campell, 2017).

The majority of local electrical codes are modeled from some version of the National

Electrical Code (NEC), which is developed by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA)

(CDC & HUD, 2006; NFPA, 2018). Currently, 19 states have implemented the 2017 NEC, 28

states have implemented earlier versions of the NEC, and 3 states have implemented their own

version of the NEC (NFPA, 2018). According to the NFPA (2018), Nevada has adopted the

2011 NEC and it is not in the process of adopting an updated version.

Although the purpose of electrical codes is to establish a standard for safety, a house that

was initially NEC compliant during its construction, could be out of date and noncompliant

according to most recent codes (Brenner, 2015; CDC & HUD, 2006). Further complicating the

issue is the decisions in some states not to adopt the newest NEC even though these updates

reflect advancements in technologies, guidelines on how to bring non-compliant homes into

compliance, and new safety strategies (Brenner, 2015).

Heating, Cooling, and Ventilation

Having a properly working heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system (HVAC) is

imperative in a region such as Southern Nevada where temperatures soar over 100°F during the

summer and linger towards freezing during the winter. According to the latest data provided by

the National Weather Service (NWS), 2016 marked the 4

th

consecutive year that Nevada led the

nation in heat related deaths (NWS, 2017). Of 50 heat-related deaths in 2016, 24 occurred in

permanent, non-mobile homes (NWS, 2017). The most vulnerable to heat related deaths are

those aged 60 and older, who accounted for half of all deaths in 2016 (NWS, 2017).

Furthermore, a functional HVAC system also effects indoor air quality by regulating moisture

14

and the flow of air into and out of the home (CDC & HUD, 2006). This has an integral role in

removing indoor air pollutants and preventing moisture build-up, which can lead to mold and

structural damage.

Landlord and Tenant Habitability Law

Policymakers have created standards to address where and how to build homes to protect

the health and safety of the public. These regulations include housing codes that prevent

developers from building potentially dangerous substandard housing and zoning codes that

ensure that a community is designed in the best interest of the health of the community (Galvan,

2006). The Tenement Act of 1840 (CDC & HUD, 2006) and the New Tenement Act of 1901

(Heathcott, 2012) in New York were pioneering in being the first laws to recognize the

relationship between housing and health by addressing the importance of proper sanitation,

indoor air, and having housing components in good repair.

States started to include habitability sections in their statutory laws to define the

responsibilities that landlords and tenants have to keep a residence in a habitable condition

(Bachelder et al., 2016; Horwitz-willis et al., 2017; Super, 2011; Wills II et al., 2017). The

regulatory and enforcement authorities for housing codes varies between and within states

(Horwitz-willis et al., 2017). Most state habitability laws are regulated by either a building,

safety, or economic and community affairs agency and are enforced at the municipal level.

Although state and local laws regarding habitability vary from state to state, they are mostly

modeled after the Uniform Residential Landlord and Tenant Act (URLTA) of 1972 (Bachelder et

al., 2016; Horwitz-willis et al., 2017; Super, 2011; Wills II et al., 2017).

Nevada’s landlord and tenant habitability laws are outlined in Chapter 118A of the

Nevada Revised Statutes (NRS). These statutes define the obligations of both the landlord and

15

tenant and the process for resolving disputes. According to Wills, et al. (2017), Nevada was an

early adopter of the habitability elements found in the URLTA and suggest that recent revisions

to the statute is an example of the state’s eagerness to keep the regulations relevant an up to date.

Implied Warranty of Habitability

URLTA and other state and local housing codes were not the first legal mechanisms to

regulate ROU habitability. The foundation of current landlord and tenant habitability law is the

concept of implied warranty of habitability (Brennan, 1999; Franzese, Gorin, & Guzik, 2016;

Gilbert, 2011; Horwitz-willis et al., 2017; Super, 2011; Wills II et al., 2017). In general, implied

warranty of habitability is a landlord’s promise to the tenant that the rental property will be in a

habitable condition throughout the leasing term (Brennan, 1999; Franzese et al., 2016; Gilbert,

2011; Super, 2011). The implied warranty of habitability can be created and defined by state and

local statutes, building codes, and case law (Super, 2011). It attaches to the rental agreement

between landlord and tenant. Brennan (1999) states that the implied warranty of habitability in

leases gave potential tenants bargaining power and protection against landlords.

The implied warranty of habitability is comparatively tenant-friendly. Before the

inclusion of the implied warranty of habitability principle in leasing contracts, tenants had fewer

rights, protections, and assurances from their landlord (Brennan, 1999; Franzese et al., 2016;

Gilbert, 2011; Mostafa, 2007). Specifically, landlords employed the caveat emptor, or “tenant

beware” practice, which limited the scope of what a landlord was responsible for, putting the

responsibility of securing specific warranties on the tenant, and often resulting in tenants losing

court cases against their landlords when housing conditions were not fit for habitation (Brennan,

1999; Franzese et al., 2016; Gilbert, 2011; Mostafa, 2007). For the most vulnerable populations

16

that are overburdened by social, economic, and health disparities, this was especially

troublesome (Wakefield & Baxter, 2010).

Although the implied warranty of habitability was a significant step in improving the

rights and protections of tenants, the process of handling landlord and tenant grievances and the

degree of enforcement differs across state and local jurisdictions (Bachelder et al., 2016; Gilbert,

2011; Horwitz-willis et al., 2017; Wills II et al., 2017). Currently, most states include some form

of implied warranty of habitability in their statutes, but the District of Columbia and four states

are void of any explicit statutory laws that create an implied warranty of habitability and are

limitedly covered by common law (Wills II et al., 2017). Arkansas is the only state without a

landlord’s warranty of habitability (Bachelder et al., 2016; Wills II et al., 2017).

Uniform Residential Landlord and Tenant Act

Seeking uniformity and modernization of landlord and tenant habitability laws in the US,

the Uniformed Law Commission (ULC) drafted the URLTA of 1972 (ULC, 1972). The ULC is

a non-partisan, non-government organization that assists states by drafting model statutory laws

(UCL, n.d.). It is up to the individual states if they want to adopt all, some, or none of the

elements in the model legislation provided by the ULC. The articles of the URLTA provide a

framework for implementing landlord and tenant laws that clearly define the responsibilities of

both the landlord and tenant to keep a home in a habitable condition and the guidelines to

remedy disputes between them. In 2015, a revised, more comprehensive version of URLTA

(RURLTA) was created. It is important to note that the sections of RURLTA that outline the

responsibilities of landlord and tenants to maintain a home in a habitable condition reference

every element outlined in the CDC’s Healthy Housing Reference Manual. RURLTA outlines the

17

following landlord and tenant responsibilities to keep the home habitable and maintained as well

as remedies for non-compliance:

Landlord Responsibilities to Maintain Premises (ULC, 2015)

1. The home must be compliant with all applicable housing, building, and health codes.

2. The home must provide effective waterproofing and protection from outdoor elements.

This covers the roof, exterior walls, windows, and doors.

3. The home must have a working and maintained plumbing system, which includes a

system for wastewater removal.

4. The home must have access to a working water supply that is able to produce hot and

cold water.

5. The home must have a working and maintained HVAC system.

6. The home must have a working electrical system

7. The home must be free of pests, such as rodents, bedbugs, or other vermin and should be

free of hazardous substances such as mold, radon, and asbestos.

8. If the home has a common area(s), they should be safe, clean, and sanitary.

9. There needs to have an appropriate number of trash receptacles.

10. Structural elements such as the flooring, walls, ceiling, and stairs need to be in good

repair.

11. Any appliances or facilities that are necessary or provided by the landlord must be in

working condition.

12. All locks on exterior doors and windows must be in working condition.

13. Any safety equipment required by law must be supplied.

Tenant’s Responsibilities to Maintain Premises (ULC, 2015)

18

1. The tenant must comply with all responsibilities required by them to abide building,

housing, and health codes.

2. The home must be kept safe and sanitary.

3. All trash must be removed in a sanitary manner.

4. Components of the plumbing system found in the home or utilized by the tenant must be

kept clean.

5. The plumbing, HVAC, and electrical systems and other facilities and appliances must be

used in a reasonable manner.

6. The tenant is responsible for making sure that no one in the home destroys, defaces,

impairs, or removes any component of the home.

7. The tenant must not disturb the use or enjoyment of other tenants in the home or on the

premises of the home.

8. The tenant must report any needed repairs or remediation in a timely manner.

9. Except for normal wear and tear, the home must be returned in the same condition as it

was during the start of the lease.

10. Unless specified in the lease, the home must be used primarily as a dwelling unit.

Selected responsibilities imposed on the landlord can be assigned to the tenant in a

separate agreement, provided that the agreement is not bound to the rent owed to the landlord

and the tenant’s inability to complete the task(s) does not exclude the landlord’s responsibilities

(ULC, 2015).

Remedies for Non-Compliance (ULC, 2015)

1. The party responsible for non-compliance must be given an official notice of the

violation.

19

2. The violating party must remedy or make significant progress remedying the problem

with 5 days for complaints categorized as essential or 14 days for complaints categorized

as non-essential. Essential complaints include access to adequate water, sanitation,

heating, electricity, and anything that endangers the immediate safety and health of the

tenant(s).

3. If the issue is not remedied, the tenant(s) have the following options depending on their

case:

a. terminate the lease

b. continue the lease and withhold rent to recover damages related to the non-

compliance, obtain injunctive relief, remedy the problem themselves and

deducting the cost of the repairs from the rent, or secure the essential service.

Nevada Habitability Law

Nevada started to incorporate elements of the URLTA in its habitability statutes in 1977

(Wills II et al., 2017) and has since revised them three times, most recently in 2007. Nevada’s

current habitability statutes regarding responsibilities, rights, and remedies mirror RURLTA

(NRS118A.290 -NRS118A.380, ULC, 2015) and in a recent study by Wills II et al. (2017), are

considered one of the strongest in the nation. The main difference between RURLTA and

Nevada’s statutes is found in the remedies section. In Nevada, a landlord is given 48 hours, not

including weekend or holidays, to remedy or make a reasonable effort to remedy a habitability

violation categorized as an essential service (NRS118A.380). Essential services include a

working HVAC system, running water, hot water, electricity, gas, and functioning door locks

(NRS118A.380). The recommendation from the RURLTA is five days, not including holidays

or weekends.

20

Under Nevada state statute, if a landlord fails to maintain the home in a habitable

condition by violating responsibilities outlined in NRS 118A.290, a tenant has the right to seek

remedies. According to NRS 118A.290, a home is not habitable when it fails to comply with

health and housing codes regarding its health, safety, fitness for habitation, or is deficient in any

of the following criteria:

(1) Effective waterproofing and protection from the external environment

(2) Plumbing system in good repair

(3) Supply of hot and cold water with fixtures in good repair that are connected to a

working sewage system

(4) HVAC system in good repair

(5) Electrical system components in good repair

(6) Adequate means for the disposal of garbage and

(7) Home and surrounding grounds are clean and sanitary at the start of the tenancy

(8) Structural elements such as the floors, walls, stairs, etc. are in good repair

(9) All supplied appliances and facilities are in good repair

However, tenants can seek remedies only if they first notify the landlord of the violation in

writing and request remediation within 48 hours for essential services and within 14 days for

non-essential services. Written notice is not required, though, if either the landlord admits to a

violation in court or the landlord receives written notice of the violation from an agency that

enforces building, housing, or health codes (NRS 118A.355 and 118A.380).

Tenants can seek these remedies only if, the violation was not related to any intentional

or negligent action of the tenant (NRS 118A.355 and 118A.380). Furthermore, to seek remedies

for non-essential services violations, tenants must also provide the landlord sufficient access to

21

the home (NRS 118A.355), while to seek remedies for an essential services violation, tenants

must be current in rent payments (NRS 118A.380). If remediation or a reasonable attempt

towards remediation is not achieved in the prescribed time frame, the tenant may seek the

following:

1. Self-help: For a repair that would cost no more than one month’s rent to fix, a tenant may

choose to remedy the violation and deduct the cost of remediation from their rent if the

landlord is given an invoice of the charges (NRS 118A.360). For an essential service

violation, the tenant may also acquire the remediation service and deduct its reasonable

cost from rent or procure replacement housing for the noncompliant period and deduct its

cost from rent (NRS 118A.355)

2. Withhold rent: Sections 118A.355 and 118A.380 state that a tenant may withhold rent

until the violation is remedied so long as the rent owed to the landlord is deposited in a

court-maintained escrow account.

3. Terminate the lease: Section 118A.355 states the tenant may terminate the lease and

recover any deposits and/or prepaid rent for a non-essential violation.

4. Seek remediation through civil court, either “actual damages” for essential or non-

essential services violations (NRS 118A.355 and 118A.380) or “such relief as the court

deems proper” for non-essential services violations (NRS 118A.355).

Clark County Landlord and Tenant Hotline Study

The CCLTHS was created to ascertain how efficient and cost-beneficial a landlord and

tenant hotline would be at addressing hazards that have the potential to cause negative health

outcomes in ROUs in Clark County, NV. This UNLV and SNHD collaborative project collects

22

information that can help fill a knowledge gap regarding the conditions of ROUs because there is

limited research on home-based hazards in Clark County, NV. The CCLTHS is managed by

UNLV and consist of two components, basic hotline services and research activities. Basic

hotline services provide guidance to callers on how to address grievances regarding hazards

found in ROUs according to NRS 118A. The research component of the study, which requires

verbal consent, allows the hotline operator to do the following: (1) obtain additional information

regarding household demographics and details of the complaint(s), (2) schedule a site inspection

performed by the SNHD, and (3) conduct a follow-up survey (Appendix C).

Basic Services Procedures

The basic services component of the CCLTHS is provided to anyone who calls the

hotline regardless whether they consent to the research component. It includes the following

steps:

1. The hotline operator determines if the caller is either a landlord, tenant, or calling on the

behalf of someone. Additionally, the hotline operator determines if the property is

categorized as a public accommodation or public housing. If the caller is calling on

behalf of someone on the lease, they are informed that the person on the lease will

eventually have to become involved. Individuals calling on the behalf of someone else

and who are not on the lease are informed that legal action is only pursuable by tenants

party to the lease. Callers who live in homes categorized as public accommodations or

public housing are not handled by the hotline and are referred to an appropriate agency

that can handle their complaint(s), such as the Southern Nevada Regional Public Housing

Authority or Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health. Public accommodations

include places that are kept, used, maintained, or held out to the public to be a place

23

where non-permanent rooming accommodations are furnished (e.g. hotels, motels, bed &

breakfast facilities, etc.).

2. After the hotline operator collects the caller’s contact information and details about the

complaint(s), the operator determines if the complaints are categorized as essential or

non-essential services as defined by NRS 118A or is considered a health and safety

hazard as described in the Seven Principles to a Healthy Home. The Seven Principles to

a Healthy Home were created by the National Center for Healthy Housing and are: (1)

keep it clean, (2) keep it dry, (3) keep it pest free, (4) keep it safe, (5) keep it contaminant

free, (6) keep it ventilated, and (7) keep it maintained. Complaints that do not fit any of

those criteria are referred to an appropriate agency that can handle their complaint(s).

3. Callers are informed about complaints under NRS 118A. They are instructed to inform

their landlord of the issue(s) in a signed and dated letter and request that the issue(s) gets

resolved. Based on the category of the complaint(s), the landlord is required to resolve

the problem or make reasonable progress towards a resolution within a specified time.

Essential complaints must be responded to within two days, not including weekends or

holidays. Non-essential complaints must be responded to with 14 calendar days. Callers

are given the option of using letter templates provided by the hotline (see Appendices A

& B).

4. Callers are provided with Nevada Legal Services’ contact information as an additional

resource and then are briefed on the research component of the CCLTHS.

Research Activities Procedures

1. The caller is informed of the study’s purpose and is asked to verbally consent if they are

interested. Once consented, the caller is assigned a case number.

24

2. The hotline operator collects additional information on household demographics and

complaint details. The specific questions are outline in the follow-up (Appendix C)

survey.

3. The caller is instructed to contact the hotline and provide details when a resolution has

been reached in the mandated time. If the problem is not resolved in the mandated time,

callers have the option to schedule a site visit by the SNHD. During a site visit, an

environmental health specialist inspects the home and provides the caller with a report

detailing the inspection and attempts to talk to the landlord. Although SNHD does not

have jurisdiction over matters between landlord and tenants, the report given to the caller

can be used in civil court if legal action is pursued.

4. The hotline operator performs a follow-up call.

Any information collected during both the basic and research components of the study are

entered into a master database managed by UNLV.

Conclusion

In summary, since the late 19

th

century, research has linked relationships between

environmental elements in the home with the health of occupants. Understanding the

significance to public health, policy makers have created regulations aimed at reducing the

incidence of negative health outcomes related to housing. As our understanding of this

relationship has grown, pertinent regulations have expanded and now include protections against

landlords who violate the warranty of habitability.

In Southern Nevada, a lack of research on both the characteristics of environmental

hazards present in ROUs and the effectiveness of landlord and tenant habitability statutes

presents a knowledge gap in public health. This knowledge gap can potentially hinder our ability

25

to accurately assess the degree to which environmental hazards in homes are negatively affecting

the health of people in Southern Nevada and the strength of the statutes created to protected

tenants from substandard housing. Understanding the relationship between the age of ROUs

and environmental hazards and how successful tenants are at resolving habitability grievances,

could help reduce this gap and improve population health.

26

Chapter 3: Methods

Study Design

The study utilized quantitative data obtained from the CCLTHS database. The database

contained 3,326 logged calls to the Hotline between March of 2014 and September of 2016. A

final dataset of 520 consented cases who answered the CCLTHS follow-up survey (Appendix C)

was utilized to answer the research questions. The follow-up survey consisted of information

that detail self-reported household demographics, descriptions of the complaint(s), and if the

hazards were remediated.

Inclusion Criteria

A final dataset of verbally consented cases that met the following inclusion criteria were

used to answer the research questions:

• Must be a tenant or landlord of a private ROU in Clark County, NV

• Must have a qualified complaint that is outlined in NRS 118A regarding the habitability

of the ROU or is considered a health and safety hazard as described in the Seven

Principles of a Healthy Home.

The final dataset did not include callers who met any of the following exclusion criteria:

• The caller is an occupant of and owner-occupied home

• The caller’s home is categorized as public housing

• The caller’s home is categorized as public accommodations.

• The caller does not reside in Clark County, NV

• The complaint is not covered in NRS 118 or the Seven Principles of a Healthy Home

• The caller does not provide verbal consent

27

Hypotheses and Methods

The final data set comprising 521 consented cases was utilized to test the following

hypotheses. All analyses utilized SPSS software (v. 24; IBM, Armonk, NJ).

Question 1: Is there a relationship between the age of the ROU and the type of environmental

hazard(s) reported?

H

01

:

There is no relationship between the age of a ROU and the environmental hazard(s)

reported.

Ha

1

: There is a relationship between the age of a ROU and the environmental hazard(s) reported.

To test this hypothesis, answers to question 2.1 of the housing demographics section and

question 1 of the hotline complaint section of the CCLTHS follow-up (Appendix C) survey were

analyzed using SPSS Version 24. The categories of reported hazards included the following: (1)

mold, (2) general maintenance, (3) bedbugs, (4) cockroaches, (5) other insect, (6) HVAC outage,

(7) odor, (8) water outage, (9) electric or gas outage, (10) rodents, (11) domestic animals, (12)

pigeons, (13) hoarder, (14) ETS, and (15) other. These hazard categories were consolidated into

5 larger groups and an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized to determine if the average

age of ROUs differed as a function of the type of environmental hazard reported. The groups

needed to be consolidated because some hazard categories had sample sizes too small to be

included in an ANOVA. The final five categories include the following:

• Pests/animals: bedbugs, cockroaches, other insects, rodents, domestic animals, and

pigeons.

• Essential services: HVAC outage, water outage, electric/gas outage

• Mold

• General maintenance

28

• Other: odor, hoarder, environmental tobacco smoke, and other

Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Bonferroni’s method to protect Type I error.

Question 2: Is there is a statistically significant difference in the proportions of hazards

remediated by tenants who pursued different levels of intervention (i.e., receiving a site

inspection from the SNHD vs. seeking legal advice after sending a complaint letter to the

landlord)?

H

02

: Tenants who pursued different levels of intervention are equally likely to get their reported

hazard remediated.

H

a2

: Tenants who pursued different levels of intervention are not equally likely to get their

reported hazard remediated.

To test this hypothesis, answers to questions 2, 2.1.1.2, and 4 of the hotline complaint

section of the CCLTHS follow-up survey (Appendix C) were analyzed. A chi-square test of

homogeneity was conducted to determine if there is a statistically significant difference in the

proportions of hazards remediated by tenants who pursued different levels of intervention.

Question3: Does the age of a home, the number of complaints made by each tenant, or complaint

category influence the likelihood of remediation?

H

03

: There is no relationship between age of a home, the number of complaints made by each

tenant, or complaint category and the likelihood of remediation.

H

a3

: There is a relationship between age of a home, the number of complaints made by each

tenant, or complaint category and the likelihood of remediation.

29

To test this hypothesis, question 2.1 of the household demographic section and questions

1 and 1.1 of the hotline complaint sections was analyzed. A binary logistic regression was

utilized to examine if there was a statistically significant relationship between the remediation of

a reported hazard and the age of a home, the number of complaints made by a tenant, or

complaint category.

IRB and Data Management

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the UNLV granted an exempt status for this

study (Appendix D). Any data, documents, or records analyzed in the thesis project were

utilized in such a way that the identities of the study participants cannot be revealed. This was

ensured by the following procedures:

• Completing the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) course on “The

Protection of Human Subjects”.

• Data files were stored in private, locked offices and on password-protected computers.

• Unique case numbers assigned to study participants were used in lieu of personal

information for reporting and publishing the thesis.

Once the thesis is complete, all hard copies of data will be shredded and electronic data

files placed in a secure, password encrypted server managed by the UNLV Department of

Environmental and Occupational Health.

30

Chapter 4: Results

Descriptive Statistics

Of the 520 consented cases in the final data set, the number of complaints made by each

tenant ranged from one to five, with 355 (68.1%) tenants registering one complaint, 125 (24.0%)

registering two complaints, 30 (5.8%) registering three complaints, 9 (1.7%) registering four

complaints, and 1 (0.2%) registering five complaints. When asked if their grievance was

resolved, 332 (63.7%) of tenants reported that no resolution was found. The number of tenants

who took their grievances civil court was 42 (8.1%). The age of ROUs was normally distributed

with a skewness of 0.782 (SE = 0.115) and kurtosis of 0.949 (SE = 0.229). The mean age of

ROUs was 29.8 years (n = 451), 95% CI [28.5, 31.1].

Hypotheses Analysis

Question 1 – Is there a relationship between the age of ROUs and the types of environmental

hazards found in them?

The hazard groupings used in the ANOVA were pests/animals (n = 111), essential

services (n =62), mold (n =180), general maintenance (n = 81), and other (n = 16) (Figure 1).

The data met the following assumptions: (1) the dependent variable, age of the home, was

measured in a continuous scale, (2) the independent variables, hazard groupings, were

categorical, (3) there was independence of observations, (4) there were no significant outliers, (5)

the dependent variable was normally distributed, and (6) there was homogeneity of variances.

The mean age of ROU’s (Figure 2) was statistically significantly different between hazard

categories, F(4, 445) = 5.11, p < 0.05. A Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed mean differences

were statistically significant between essential services ( = 35.27, SD = 16.59) and mold ( =

31

27.64, SD = 12.77; p < 0.05) and essential services and other (= 23.25, SD = 11.62; p < 0.05).

Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected.

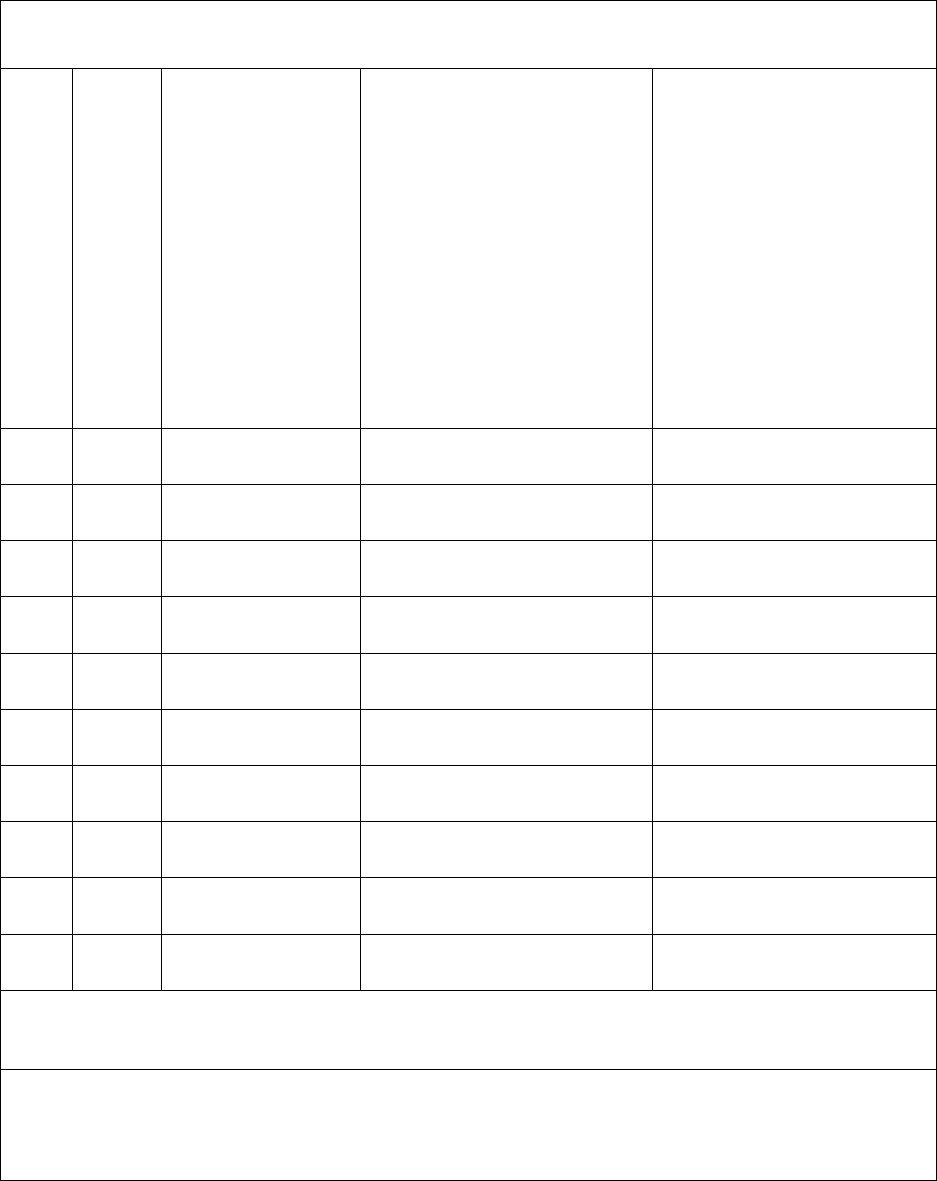

Figure 1. The Number of Complaints by Hazard Category

Figure 2. The Mean Home Age in years by Hazard Category

111

62

180

81

16

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

Pests/Animals Essential Services Mold General

Maintenance

Other

Number of Complaints

Hazard Category

Number of Complaints by Hazard Category

29.59

35.27

27.64

31.99

23.25

15

20

25

30

35

40

Pest/Animals Essential Services Mold General

Maintenance

Other

Mean Home Age

Hazard Category

32

Question 2 – Is there is a statistically significant difference in the proportions of hazards

remediated by tenants who pursued different levels of intervention?

The data met the following assumptions: (1) the dependent variable, remediation, was

dichotomous, (2) the independent variable, intervention level, was polytomous (3) there was

independence of observations, and (5) the sample size was adequate. The data shows that 16.7%

of tenants who only sent a letter to their landlord were able to get their hazard remediated

compared to 35% of tenants who sent a letter and received a site inspection by the SNHD, and

36.8% of tenants who sent a letter, received a site inspection, and sought legal advice. A chi-

square test of homogeneity suggested that there was no statistically significant difference in the

proportions of hazards remediated by tenants who pursued different levels of intervention, X

2

=

1.11, p = 0.292. Therefore, the null hypothesis was not rejected.

Question 3 – Does the age of a home, the number of complaints made by each tenant, or

complaint category influence the likelihood of remediation?

A binary logistic regression was performed to determine if the age of a home, the number

of complaints made by each tenant, or whether a complaint was categorized as essential or non-

essential had an influence on the likelihood of remediation. A Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-

of-fit test indicated that the model was a good fit to the data, X

2

(8) = 2.69, p = 0.952.

Additionally, the data fit the following assumptions: (1) the dependent variable, remediation, was

dichotomous, (2) the independent variables, age of home, number of tenant complaints, and

complaint category, were measured on a continuous scale, (3) there was independence of

33

observations and both dependent and independent variables were exhaustive and mutually

exclusive, and (4) the sample sizes of each independent variable were adequate.

For each increase in home age of 1 year, the likelihood of remediation was decreased by

2.5%. For tenants with one complaint, the odds of remediation were 1.75, (95% CI = 1.06 -

2.89], times that of tenants with multiple complaints. For complaints categorized as essential,

the odds of remediation were 4.15, (95% CI = 1.36 - 12.7) times that of complaints categorized

as non-essential. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected.

34

Chapter 5: Discussion, Conclusions, and Recommendations

Discussion

The data showed that the oldest homes were associated with essential services complaints

(x

̅

= 35.27 years), followed by general maintenance (x

̅

= 31.99 years), pests/animals (x

̅

= 29.59

years), mold (x

̅

= 27.64 years), and other (x

̅

= 23.25 years). Essential services pose the most

immediate risk to the health and well-being of tenants and those who live in older homes are

most vulnerable. Understanding the mean age of the homes and most common hazards may be

useful for public health practitioners to implement primary prevention measures. For example,

the age of the home may be a useful metric to help target certain homes for inspections and

evaluations of meeting habitability requirements prior to any failures or imminent risks to health

and safety. Additionally, this information may be useful for local policy makers, as well as

landlords, in anticipating needs and securing adequate funding necessary to mitigate such

hazards.

Although statistically significant, the mean age difference between essential services and

hazards categorized as other provided little insight considering it was an aggregate of four

smaller groups with an overall small sample size compared to the other categories. Conversely,

it is interesting that compared to the other groups, mold was associated with newer homes. This

coincides with research that suggest that the introduction of gypsum drywall into the structural

elements of homes increased the chances of mold growth compared to plaster and lathe (Vesper,

Wymer, Cox, & Dewalt, 2016). This is due to the binders and additives that are found in the

gypsum drywall, which fosters an ideal environment for fungal growth (Vesper et al., 2016).

Although the data did not suggest a statistically significant difference in the proportions

of hazards remediated by tenants who pursued different levels of intervention, the proportion of

35

tenants who got their hazard remediated did increase with each additional intervention. The

proportion of tenants that were able to get their hazards remediated was more than two times

higher in those who sought more than one level of intervention. The sample size for each

intervention group was relatively small and could be an explanation for the statistical

insignificance. Each level of intervention, a site inspection or legal advice, places the tenant with

an expert in either the environmental hazard or law profession. This could have led to tenants

making more informed decisions; ultimately providing them leverage against their landlord.

Qualitative data from tenants who pursed civil litigation suggests that those who made

less informed decisions also inadvertently placed themselves in precarious situations, showing

some support for this claim. Out of the 41 tenants who took their landlord to civil court, 11 were

ultimately evicted because they failed to pay rent while they were contesting the damages with

their landlord. None of the 11 evicted tenants sought legal advice. Had they understood the

basic tenets of Nevada’s landlord and tenant habitability statutes, they would have known that

contesting grievances with their landlord does not excuse them from paying rent.

The data from the third research question suggested that to be in the best position to get a

hazard remediated, a tenant should reside in a newer home and have one complaint categorized

as an essential service. This is of concern because the mean age of ROUs in each hazard

category ranged from 23.25 to 35.27 years and older ROUs will inherently observe more housing

related hazards than newer ones. For people who are most likely to live in older homes such as

lower-income families and the elderly, this can further complicate their living situation. With

less available resources, they might not have the means to remediate these problems.

It should be no surprise that the odds of remediation of essential service complaints were

4.15 times that of non-essential complaints. The absence of essential services, such as a working

36

HVAC system during the summer in Clark County, can lead to immediate negative health

outcomes. The nature of the complaint and the short time allotted by the NRS to remedy it could

give the tenant more leverage when seeking remediation from their landlord. The issue here is

the number of potential non-essential complaints that are not remediated. Non-essential

complaints, such as general maintenance issues, might not pose the degree of immediate risks

relative to essential services, but often are associated with subsequent failures in essential service

complaints. Greater attention to these issues could reduce the incidence and severity of future

complaints in ROUs.

Finally, the odds of remediation were significantly higher if the tenant had a single

complaint. This is significant because deficiencies in one aspect of the home is indicative of

deficiencies in another (CDC & HUD, 2006). The data shows that hazards were found in older

homes, which will inherently observe multiple hazards at a time. This is another barrier for those

who are most likely to live in older homes. If the tenant elects to file one complaint at time to

increase the odds of remediation, this would increase the time spent in a home not fit for

habitation. Additionally, the decrease in odds of remediation associated with multiple

complaints could be indicative of the financial burden placed on the homeowner to keep a home

in good repair. This could signal a need to educate homeowners about the associated costs of

keeping a home in good repair and the advantages of proactively addressing potential

deficiencies in the home before they become hazards.

Limitations

This study was not without limitations. The data from this study were self-reported

information detailed in the CCLTHS follow-up survey (Appendix C). This could have created

inaccuracies that potentially led to misleading data. For example, the complaints made to the

37

hotline were never verified, unless the tenant qualified and opted for a SNHD site inspection. In

this study, only 40 out of 521 cases received site inspections. Furthermore, there was no way to

verify that each case followed the recommended advice provided by the hotline operator. Only

53 cases provided the hotline with a copy of the letter sent to their landlord.

Another limitation was the sample size. The total number of study participants might

have not been representative of the Clark County renter community. Many tenants might have

not been aware of the existence of the hotline because the only link to it can be found on the

SNHD website. Additionally, those that did seek out the assistance of the hotline may have been

tenants who had already requested remediation from their landlord but felt as if remediation was

not taking place in, what they perceived as, an acceptable amount of time. Also, those who lack

the financial and/or social capital might have been reluctant to call the hotline. This includes

those who fear landlord retaliation and/or have citizenship and/or language barriers.

Furthermore, the extent of tenant participation could have been limited because they could have

been evicted or moved before a resolution was found.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In a side-by-side comparison, Nevada’s landlord and tenant habitability statutes mirrors

RURLTA, the model legislation, and is considered one the strongest in the nation as written.

Despite this, 63% of tenants were not able to find some form of resolution related to hazards

reported to the hotline. This study suggests that tenants who are most likely to encounter an

environmental hazard in their homes are the least likely to get it remediated by their landlord.

Tenants were less likely to get their hazard remediated by their landlords if they had multiple

complaints, lived in an older home, or had a non-essential complaint. The key is to bridge the

disconnect between those in most need and the legislation created to protect them. Regulatory

38

changes, expanding and improving the hotline, and providing landlords with additional resources

could help bridge this disconnect.

Regulatory Changes

The data suggest that there was a significant disparity between the likelihood of

remediation of an essential service and non-essential service. Amending the current NRS code

to reduce the number of days needed to remediate or make reasonable progress towards

remediation of a non-essential service could increase the probability of remediation. Reducing

the amount of time in half, from 14 days to 7 days, could increase the landlord’s urgency to

remediate and reduce the likelihood of the tenant not following through, defaulting on rent, or

moving out This change would not be unprecedented since the amount of time to remediate or

make reasonable progress towards remediation of an essential service is 48 hours, which is three

days shorter than RURLTA standard.

Another regulatory change that could improve issues with ROU habitability would be

requiring a mandatory inspection before a lease is finalized, ensuring a baseline of quality

outlined by the NRS is met. The most cost-effective option could require both parties to inspect

the house together to identify and address any violations of the NRS code regarding habitability.

The other option could require the landlord to pay for a professional inspection, such as those

conducted before the sale of a home. Although the upfront cost of this option would be less cost-

effective for the landlord, an inspection performed by a professional could yield findings that

could be missed by the landlord. These findings could save the landlord time and money in the

long term.

39

Regulatory agencies such as code enforcement and the SNHD can also mandate that all