Why Google Dominates Advertising Markets

Competition Policy Should Lean on the

Principles of Financial Market Regulation

Dina Srinivasan

*

* Since leaving the industry, and authoring The Antitrust Case Against Face-

book, I continue to research and write about the high-tech industry and competition,

now as a fellow with Yale University’s antitrust initiative, the Thurman Arnold Pro-

ject. Separately, I have advised and consulted on antitrust matters, including for news

publishers whose interests are in conflict with Google’s. This Article is not squarely

about antitrust, though it is about Google’s conduct in advertising markets, and the

idea for writing a piece like this first germinated in 2014. At that time, Wall Street was

up in arms about a book called FLASH BOYS by Wall Street chronicler Michael Lewis

about speed, data, and alleged manipulation in financial markets. The controversy

put high speed trading in the news, giving many of us in advertising pause to appre-

ciate the parallels between our market and trading in financial markets. Since then, I

have noted how problems related to speed and data can distort competition in other

electronic trading markets, how lawmakers have monitored these markets for con-

duct they frown upon in equities trading, but how advertising has largely remained

off the same radar. This Article elaborates on these observations and curiosities. I am

indebted to and thank the many journalists that painstakingly reported on industry

conduct, the researchers and scholars whose work I cite, Fiona Scott Morton and Aus-

tin Frerick at the Thurman Arnold Project for academic support, as well as Tom Fer-

guson and the Institute for New Economic Thinking for helping to fund the research

this project entailed. I remain deeply grateful to the many scholars that generously

shared their feedback, comments, and insight, often on matters well outside of my

area of expertise: Eric Budish, Kevin Haeberle, Scott Hemphill, Michael Kearns, Lina

Khan, Jonathan Macey, Doug Melamed, John Morley, Gabriel Rauterberg, Thomas

Philippon, Marc Rotenberg, Ashkan Soltani, and Chester Spatt, amongst others. I also

warmly thank John Schwall and Rick Arney for helping me to better appreciate the

parallels to financial markets, Zach Edwards for critical thinking and research assis-

tance, Jennifer LaCosse for careful edits and thoughtful suggestions, Chaaru Deb for

excellent legal research assistance, and the editors at the STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW

REVIEW for outstanding editorial support. The views and errors therein are my own.

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

56

24 STAN. TECH. L. REV. 55 (2020)

ABSTRACT

Approximately 86% of online display advertising space in the U.S. is bought

and sold in real-time on electronic trading venues, which the industry calls “ad-

vertising exchanges.” With intermediaries that route buy and sell orders, the

structure of the ad market is similar to the structure of electronically traded fi-

nancial markets. In advertising, a single company, Alphabet (“Google”), simul-

taneously operates the leading trading venue, as well as the leading intermedi-

aries that buyers and sellers go through to trade. At the same time, Google itself

is one of the largest sellers of ad space globally. This Article explains how Google

dominates advertising markets by engaging in conduct that lawmakers prohibit

in other electronic trading markets: Google’s exchange shares superior trading

information and speed with the Google-owned intermediaries, Google steers buy

and sell orders to its exchange and websites (Search & YouTube), and Google

abuses its access to inside information. In the market for electronically traded

equities, we require exchanges to provide traders with fair access to data and

speed, we identify and manage intermediary conflicts of interest, and we require

trading disclosures to help police the market. Because ads now trade on electronic

trading venues too, should we borrow these three competition principles to pro-

tect the integrity of advertising?

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

57

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 58

II. ELECTRONIC TRADING MARKETS .............................................................. 69

A. Advertising Market Reflects the Structure of an Electronic Trading

Market ..................................................................................................... 69

B. Common Competition Problems in Electronic Trading Markets ........... 77

C. The Competition Principles We Apply in the Equities Trading Market 80

III. GOOGLE DOMINATES ONLINE ADVERTISING MARKETS BY ENGAGING IN

CONDUCT LAWMAKERS PROHIBIT IN OTHER ELECTRONIC TRADING

MARKETS ..................................................................................................... 86

A. Google Has Information and Speed Advantages .................................... 88

1. Google Acquires Leading Ad Server DoubleClick ........................... 88

2. DoubleClick Ad Server Starts to Play Favorites When Sharing User

Identity ............................................................................................. 94

3. Google-Owned Intermediaries Have an Information Advantage on

Google’s Exchange ........................................................................... 98

4. Consumer Privacy Offered as Reason for Information Asymmetry

....................................................................................................... 102

5. Google-Owned Intermediaries Have a Speed Advantage on Google’s

Exchange ........................................................................................ 107

B. Discriminatory Routing of Orders and More Speed Races .................. 117

1. Routing Orders to Google’s Exchange and Owned Properties ..... 117

2. Market Creates Invention to Circumvent Routing Restrictions and

Set Own Speeds ............................................................................. 127

3. Google AMP Speed Protocol Restricts Trading Through Non-

Google Venues ................................................................................ 132

4. Google Search “Speed Update” Further Restricts Trading Through

Non-Google Venues ....................................................................... 144

C. Inside Information Abuses .................................................................... 149

1. Google’s Ad Server Shares Information About Competitors’ Trading

Activity with Google’s Exchange and Buying Tools, Permitting

Them to Trade Ahead of Orders .................................................... 149

2. Google Amends Terms and Conditions to Breach “Ethical Walls”

....................................................................................................... 154

IV. POLICY CONSIDERATIONS ........................................................................ 158

A. Advertising Exchanges Should Provide Fair Access to Information and

Speed ..................................................................................................... 158

B. Steps Toward Identifying and Managing Intermediary Conflicts of

Interest .................................................................................................. 162

1. Structural Separations ................................................................... 162

2. Conduct and Disclosure Rules ...................................................... 163

3. Transparency and Disclosure ........................................................ 171

V. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................. 172

VI. APPENDIX .................................................................................................. 174

A. Timeline ................................................................................................ 174

B. Screenshot of Auction Timestamp Transparency ................................. 175

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

58

I. INTRODUCTION

The business of advertising has changed drastically over the last two

decades. In the past, advertising contracts were negotiated in person—

think Mad Men-type advertising and publishing executives over two-

martini lunches off Madison Avenue. Today, the largest category of ad-

vertising, online advertising, is rarely negotiated by people at all. Ad-

vances in technology allow ad space to be bought and sold electronically

through centralized trading venues at high speeds, without people ever

meeting face-to-face. When a user visits a website, the ad space on a page

is instantly routed into one or more of these venues. There, the space is

auctioned in real-time to the highest bidder. At the conclusion of these

auctions, the advertisers’ ads return and display to the user in time for

the page to load and before the user has noticed anything has occurred.

The user just sees ads targeted to them, say one for Barclays bank.

The rise of electronic ad trading, widely known today as “program-

matic advertising,” paralleled the rise of electronic trading across various

sectors of the economy. In 2005, the New York Stock Exchange merged

with an electronic trading company, sunsetting the buying and selling of

stock on its iconic trading floor on Wall Street.

1

Around this time, early

advertising technology company Right Media launched the RMX “adver-

tising exchange,” the first-ever electronic trading venue for ads.

2

Just like

that, by “borrowing tactics from Wall Street,” advertising went from be-

ing a relationship business to a commodity business, with publishers and

advertisers transacting with each other in an electronic spot market.

3

1

. NYSE Approves Merger with Electronic Trading Company, N.Y. TIMES (Dec.

7, 2005), https://perma.cc/QR3Y-KMX2.

2

. Adrianne Jeffries, How to Succeed in Advertising (and Transform the Inter-

net While You’re at It), N.Y. MAG.: INTELLIGENCER (May 31, 2018),

https://perma.cc/W7CG-4LLA (discussing the history of Right Media).

3

. Stephanie Clifford, Leftover Ad Space? Exchanges Handle the Remnants,

N.Y. TIMES (July 28, 2008), https://perma.cc/UDC4-Q7LN.

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

59

The efficiencies promised by this new way of trading caught on like

wildfire. By late 2009, the RMX exchange, which Yahoo! acquired in 2007

for $680 million, was processing 9 billion ad spaces daily.

4

Since then, the

percentage of ads traded in this fashion has steadily increased. In 2021, it

is estimated that 87.5% of all online display ad space in the United

States—including that belonging to news publishers such as The Wash-

ington Post and The Des Moines Register—will trade programmatically.

5

Since the advent of electronic ad trading, however, the market has

become less competitive. At first, the biggest names in tech—including

Microsoft, Yahoo!, AOL and Alphabet (“Google”)—competed vigorously

with each other. These tech companies initially provided sellers (e.g.,

publishers like newspapers) and buyers (i.e., advertisers) with more

choices when deciding which exchanges and other trading middlemen to

use.

6

Today, a single company, Google, simultaneously operates the lead-

ing exchange and the leading middlemen (i.e., intermediaries) that pub-

lishers and advertisers must use to trade.

7

4

. Yishay Mansour et al., Doubleclick Ad Exchange Auction 2, (2012) (un-

published manuscript), https://perma.cc/T5L4-JS4Y (noting Right Media average

daily trades).

5

. Lauren Fisher, US Programmatic Ad Spending Forecast 2019, EMARKETER

(Apr. 25, 2019), https://perma.cc/852B-PRUA (estimating 87.5% of online display

ads will trade programmatically in 2021). Note, websites can sell their ad space

in open or private exchanges. Data from news publisher trade association Digital

Content Next suggests that approximately 75% of the inventory of large and mid-

dle-tier U.S. publishers currently trades in open exchanges. One would imagine

that the percentage increases if one includes small and local publishers across the

heartland. See Jason Kint (@jason_kint), TWITTER (May 12, 2020),

https://perma.cc/2NPY-SEZT.

6

. For competition in the exchange market in the late 2000s, see

AdExchanger Staff, infra note 33 and further discussion in Part III.

7

. The company formerly known as Google was renamed Alphabet Inc. in

2015, at which point Google became a subdivision of the parent organization.

Indirect proof of market power in the form of market share information is noto-

riously difficult to construct with publicly available information. However, sev-

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

60

In addition to the market becoming more concentrated, it exhibits

characteristics that would trigger concerns in other electronic trading

markets: market growth is distorted, trading costs—between 30% to 50%

of the trade—are high and non-transparent, and conflicts of interests

abound.

8

For example, on top of operating the largest exchange, as well

eral public reports on market shares support the proposition that Google oper-

ates the leading exchange, buy-side software, and sell-side software in the mar-

ket today. See COMPETITION AND MKTS. AUTH., ONLINE PLATFORMS AND DIGITAL

ADVERTISING: MARKET STUDY FINAL REPORT 20 (2019), https://perma.cc/3GKR-

YJ5J [hereinafter CMA FINAL REPORT] (estimating that in the UK, Google has a

50-60% share of the advertising exchange market, 90+% share of the ad server

sell-side software market, and 50-60% of the enterprise DSP buy-side software

market); Data Processing in the Online Advertising Sector, Opinion No. 18-A-03,

AUTORITÉ DE LA CONCURRENCE, at 86 ¶ 218 (Mar. 6, 2018), https://perma.cc/X7ZQ-

NM6U [hereinafter AUTORITÉ DE LA CONCURRENCE] (finding that Google’s enter-

prise DSP buy-side software—previously called DoubleClick Bidding Manager

or DBM but since renamed DV360—generates the most revenue and has signifi-

cant growth and that Google “has held a leading position” in the ad serving sell-

side software market since its acquisition of DoubleClick); Joe Mandese, Google

Discloses Results of “Exchange Bidding,” Boosts Publisher Yield >40%, MEDIAPOST:

DIGIT. NEWS DAILY (Feb. 16, 2018), https://perma.cc/GN5X-N8ZZ (stating that the

DoubleClick ad server is “by far the dominant ad server used by advertisers,

agencies and digital publishers”); Keach Hagey & Vivien Ngo, How Google Edged

Out Rivals and Built the World’s Dominant Ad Machine: A Visual Guide, WALL ST. J.

(Nov. 7, 2019), https://perma.cc/DKC7-D5MA (reporting that Google’s exchange,

selling tools, and buying tools are the leading ones in the market and stating that

“[m]ore than 90% of large publishers use the Google ad server, DoubleClick for

Publishers, according to interviews with dozens of publishing and ad execu-

tives”); Allen Grunes, Google’s Quiet Dominance Over the “Ad Tech” Industry,

FORBES (Feb. 26, 2015), https://perma.cc/P84T-7GX3 (discussing the leading posi-

tion of Google’s buying tools Google Ads and DoubleClick Bid Manager, which

is now called DV360).

8

. Several sources deal with the question of trading costs. See Alex Barker,

Half of Online Ad Spending Goes to Industry Middlemen, FIN. TIMES (May 5, 2020),

https://perma.cc/Z3H4-JLBM; Ross Benes, Why Tech Firms Obtain Most of the

Money in Programmatic Ad Buys, EMARKETER (Apr. 16, 2018),

https://perma.cc/96RE-5HMA (industry analysts from Warc estimating interme-

diaries collectively charge 55% of programmatic spend worldwide, based on data

shared by advertising agency Magna Global).

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

61

as the largest intermediaries trading on its exchange, Google has another

conflict of interest.

9

Google not only sells ad space belonging to third-

party websites, it sells ad space appearing on its own sites, Google Search

and YouTube. When a small business uses Google’s intermediary tool,

called Google Ads, to bid on and purchase ad space trading on ex-

changes, this tool steers that advertiser towards which ad space to buy.

The effects of this conflict of interest are predictable. In 2007, approx-

imately 64% of Google advertising revenue went to Google properties,

including Google Search and YouTube. The remaining portion went to

non-Google properties, like The Post and The Register, that also sell their

ad space through Google’s intermediary tools and exchange.

10

Almost

9

. Note, according to some estimates, Google’s buy-side intermediaries—

the buying tools that small and large advertisers use to trade—account for the

plurality if not the majority of buying volume on Google’s exchange. See Kean

Graham, How to Increase Auction Pressure in Ad Exchange, MONETIZEMORE (July 8,

2016), https://perma.cc/BA8B-2YZV (stating that Google Ads, formerly known as

AdWords, is “currently the largest buyer of inventory on the [Google] Ad Ex-

change”); Hagey & Ngo, supra note 7 (stating that media company News Corp.

did not switch from Google to a rival intermediary, because doing so would jeop-

ardize 40% to 60% of the demand the publisher receives in Google’s exchange

from Google’s proprietary demand, Google Ads).

10

. In Google’s annual 10-K SEC filings, Google breaks down its advertis-

ing revenue as going to “Google properties” or “web sites of Google Network

members.” The term “Google Network members” refers to non-Google websites

on which Google places advertising. In its 2017 10-K, Google explains that it gen-

erally accounts for third-party revenue on a gross basis: “For ads placed on

Google Network Members’ properties, we evaluate whether we are the principal

(i.e., report revenues on a gross basis) or agent (i.e., report revenues on a net ba-

sis). Generally, we report advertising revenues for ads placed on Google Net-

work Members’ properties on a gross basis, that is, the amounts billed to our

customers are recorded as revenues, and amounts paid to Google Network Mem-

bers are recorded as cost of revenues. Where we are the principal, we control the

advertising inventory before it is transferred to our customers. Our control is ev-

idenced by our sole ability to monetize the advertising inventory before it is

transferred to our customers, and is further supported by us being primarily re-

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

62

every year since 2004 this split has widened, in Google’s favor.

11

By Q1

2020, the share going to Google properties had increased to 85%.

12

The

sponsible to our customers and having a level of discretion in establishing pric-

ing.” In 2004, Google buying tools allocated approximately 50% of advertising

revenue to Google's proprietary properties, such as Search, and the other 50% to

non-Google websites selling their ads through Google's buying tools and adver-

tising exchange. Google Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Mar. 30, 2005),

https://perma.cc/5A4Y-8EY4. It was in 2006 that Google acquired YouTube. An-

drew Ross Sorkin & Jeremy W. Peters, Google to Acquire YouTube for $1.65 Billion,

N.Y. TIMES (Oct. 9, 2006), https://perma.cc/5TG8-8BVE. In 2005, Google's share of

advertising revenue increased to, approximately, 55%; 2006, 60%; 2007, 65%;

2008, 68%; 2009, 68%; 2010, 68%; 2011, 71%; 2012, 71%; 2013, 73%; 2014, 75%; 2015,

77%; 2016, 80%; 2017, 81%, 2018, 82%; 2019, 84%. Google Inc., Annual Report

(Form 10-K) (Mar. 16, 2006), https://perma.cc/Y272-BRAP; Google Inc., Annual

Report (Form 10-K) (Mar. 1, 2007), https://perma.cc/H4ZJ-FL7B; Google Inc., An-

nual Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 15, 2008), https://perma.cc/W6FU-AA2T; Google

Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 13, 2009), https://perma.cc/5PZY-UZS5;

Google Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 12, 2010), https://perma.cc/7B6E-

REEV; Google Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 12, 2011),

https://perma.cc/9ZKX-XPKL; Google Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Apr. 23,

2012), https://perma.cc/YS3R-TLE4; Google Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Jan.

29, 2013), https://perma.cc/3W45-M9R9; Google Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K)

(Feb. 11, 2014), https://perma.cc/79A2-6TCT; Google Inc., Annual Report (Form

10-K) (Feb. 6, 2015), https://perma.cc/7DJZ-FD8S; Google Inc., Annual Report

(Form 10-K) (Feb. 11, 2016) https://perma.cc/EU2M-T6QC; Alphabet Inc., Annual

Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 2, 2017), https://perma.cc/4QKP-UUZJ; Alphabet Inc.,

Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 5, 2018), https://perma.cc/22HL-SSSP; Alphabet

Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 4, 2019), https://perma.cc/ELZ2-AC93; Al-

phabet Inc., Annual Report (Form 10-K) (Feb. 3, 2020), https://perma.cc/RWE8-

27PB. For a visual graph of this split, see Appendix A.

11

. Google Inc. (2005-2016), supra note 10; Alphabet Inc. (2017-2020), supra

note 10.

12

. See Alphabet Inc., Quarterly Report (Form 10-Q) (March 31, 2020),

https://perma.cc/7872-G8ZW. In this filing, Google breaks down advertising rev-

enue as revenue for “Google properties” and “Google Network Member Proper-

ties.” Here, Google properties includes “Google Search & other properties and

YouTube.” Id. at 33. Google goes on to say that, “Google Search & other consists

of revenues generated on Google search properties (including revenues from

traffic generated by search distribution partners who use Google.com as their

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

63

lion’s share of Google’s $134 billion in advertising revenue went to

Google’s own.

Problems of distorted growth then extend across the market. Over

the last ten years, the online advertising market has enjoyed double-digit

year-over-year growth.

13

However, the majority of advertising revenue

and growth has gone to large firms like Google and Facebook that both

sell their own ad space and simultaneously run an electronic market-

place.

14

Transparency in the advertising market is also minimal. When small

businesses use the Google Ads tool to bid on ad space belonging to third-

party publishers from Google’s exchange, Google does not disclose to

them the price that the ad space actually cleared for and it appears Google

default search in browsers, toolbars, etc.) and other Google owned and operated

properties like Gmail, Google Maps, and Google Play; YouTube ads consists of

revenues generated primarily on YouTube properties; and Google Network

Members’ properties consist of revenues generated primarily on Google Net-

work Members’ properties participating in AdMob, AdSense, and Google Ad

Manager.” Id.

13

. PricewaterhouseCoopers, Internet Advertising Revenue Report: 2019 First

Six Months Results, INTERACTIVE ADVERT. BUR. (Oct. 2019), https://perma.cc/YX8X-

72EC (displaying year-over-year growth by quarter from 1996 through Q2 2019).

14

. Lauren Fisher, Digital Display Advertising 2019, EMARKETER (Jan. 22,

2019), https://perma.cc/4UVF-JGHX (estimating that Google and Facebook will

account for 52% of the display online advertising market in the U.S. in 2019);

Michael Barthel, 5 Key Takeaways About the State of the News Media in 2018, PEW

RSCH. CTR. (July 23, 2019), https://perma.cc/SJ25-45VC (summarizing that digital

ad revenue has grown exponentially but that the majority goes to Google and

Facebook). Outside of Google, Facebook, and Amazon, some even estimate that

the online advertising market is shrinking. See, e.g., Peter Kafka, Google and Face-

book Are Booming. Is the Rest of the Digital Ad Business Sinking?, VOX (Nov. 2, 2016),

https://perma.cc/QAZ6-6V9K (reflecting comments by industry analyst Brian

Weiser and publisher trade association executive Jason Kint). Finally, for docu-

mentation on the auction marketplaces run by Facebook and Amazon, see Face-

book Audience Network, Solutions Overview, https://perma.cc/KYK5-HPUG (last

visited Sept. 29, 2020). See also Amazon Publisher Services, Unified Ad Marketplace,

https://perma.cc/82YF-AX7B (last visited Sept. 29, 2020).

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

64

can arbitrage advertisers’ bids across two Google-controlled market-

places—a fact that may go unnoticed by these small mom-and-pop busi-

nesses due to the complexity of Google’s terms.

15

In effect, the counter-

party to these advertisers is often Google, though they may be under the

illusion that Google is their agent. At the same time, Google does not dis-

close to the publishers on the other ends of these trades what their space

ultimately sold for and how much Google keeps as its share.

16

15

. Google explains how its auctions and pricing work across multiple,

different documents. See Google Ads Help, How the Google Ads Auction Works,

GOOGLE, https://perma.cc/6NV9-43XK (last visited Sept. 29, 2020); Google Ads

Help, How Google Ad Manager Works with Google Ads, GOOGLE,

https://perma.cc/X6UQ-AN7S (last visited Sept. 29, 2020); Google Ads Help,

About the Display Network Ad Auction, GOOGLE, https://perma.cc/8P3M-VPJ3 (last

visited Sept. 29, 2020); Google Ads Help, About the Google Display Network,

GOOGLE, https://perma.cc/6582-YRSK (last visited Sept. 29, 2020). When taken to-

gether, the terms appear to permit Google to process bids that advertisers submit

via Google’s buying tool for small advertisers called Google Ads through two

different Google marketplaces (auctions). In other words, Google Ads hosts a

first auction, then Google Ads acts as the “buyer” in Google’s exchange, so that

Google simultaneously acts on the buy-side and the sell-side. In a recent submis-

sion to the Australian competition authority, Google implicitly confirms this

practice. See DANIEL S. BITTON & STEPHEN LEWIS, CLEARING UP MISCONCEPTIONS

ABOUT GOOGLE’S AD TECH BUSINESS 48 (May 5, 2020), https://perma.cc/WT2W-

DD74. At a 2019 conference for antitrust experts, Google chief economist Hal

Varian confirmed that Google can act on both the buy-side and the sell-side at

the same time and explained that Google uses a “formulaic apportionment” to

price ads when Google participates on both sides of a transaction. Stigler Center,

2019 Antitrust and Competition Conference, Pt. 11: Fireside Chat, YOUTUBE, at 1:01:13

(June 21, 2019), https://perma.cc/K2RR-UTCT. Finally, another point to consider

is that arbitrage, hidden fees, and undisclosed kickbacks may be a pervasive

problem in this electronic trading market. See Sarah Sluis, Investigation: DSPs

Charge Hidden Fees – And Many Can’t Afford to Stop, ADEXCHANGER (Jan. 10, 2018),

https://perma.cc/7GHG-KWDC.

16

. Websites that sell ads in Google’s exchange can see buyers’ clearing

prices via the centralized market reports that Google shares back with sites.

However, the buyers here are the intermediaries, such as Google Ads, not adver-

tisers.

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

65

High trading costs in this market also affect consumers. As a general

matter, if publishers like The Post and The Register make less money sell-

ing ads, they have less to re-invest into the business of investigative jour-

nalism and news. But the news business globally is already struggling. In

the last decade and a half, this sector in the U.S. has shed 51% of news-

room jobs, paywalls and subscription prices have increased, and 20% of

newspapers have closed.

17

This contraction has led some economists to

urge lawmakers to think about democracy and “citizen welfare” when

considering competition problems in advertising.

18

Lawmakers, antitrust enforcers, and academics are concerned about

distorted growth and high trading costs, which ultimately harm con-

sumer welfare. As a result, they have been asking, why is competition not

working better? In the U.S. and globally, governments are investigating

whether Google has monopolized advertising markets or restrained com-

petition by engaging in specific conduct that violates competition laws.

19

17

. See generally Felix Simon & Lucas Graves, Across Seven Countries, the

Average Price for Paywalled News is About $15.75/Month, NIEMANLAB (May 8, 2019),

https://perma.cc/D8CF-CN46 (surveying rise of paywalls); Freddy Mayhew,

More Paywalls Going Up Online as News Publishers Face Shrinking Share of Ad Reve-

nue and Try to Fight Back Against Ad-Blockers, PRESSGAZETTE (May 15, 2018),

https://perma.cc/CHR2-SBJC; Elizabeth Grieco, U.S. Newspapers Have Shed Half of

Their Newsroom Employees Since 2008, PEW RSCH. CTR. (Apr. 20, 2020),

https://perma.cc/NN29-Z36V (“The number of newspaper newsroom employees

dropped by 51% between 2008 and 2019, from about 71,000 workers to 35,000.”);

PENELOPE MUSE ABERNATHY, THE EXPANDING NEWS DESERT (UNC Ctr. for Inno-

vation and Sustainability in Loc. Media ed., 2018) (finding total number of U.S.

newspapers declined from 8,891 in 2004 to 7,112 in 2018).

18

. STIGLER COMMITTEE ON DIGITAL PLATFORMS, FINAL REPORT (Stigler Ctr.

for the Study of the Economy and the State ed., 2019) [hereinafter STIGLER

COMMITTEE REPORT] (discussing how the news market in democratic societies

shares features of a public good and how either concentration in news outlets or

increased news prices harms “citizen welfare”).

19

. See Tony Romm, 50 U.S. States and Territories Announce Broad Antitrust

Investigation of Google, WASH. POST (Sept. 9, 2019), https://perma.cc/K8LA-NA2H;

Keach Hagey & Rob Copeland, Justice Department Ramps Up Google Probe, With

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

66

Do digital markets naturally tend to monopolize because of network ef-

fects?

20

Or has Google monopolized these markets by unlawfully exclud-

ing competition?

21

At the same time, economists and other scholars have

Heavy Focus on Ad Tools, WALL ST. J. (Feb. 5, 2020), https://perma.cc/CV82-T6K8

(reporting that the U.S. Justice Department's antitrust probe into Google is focus-

ing heavily on Google's advertising products); Silvia Amaro, EU Starts New Pre-

liminary Probe into Google and Facebook’s Use of Data, CNBC (Dec. 2, 2019),

https://perma.cc/BL8S-8WFU; Mark Sweney, Google and Facebook Under Scrutiny

over UK Ad Market Dominance, GUARDIAN (July 3, 2019), https://perma.cc/7EQR-

X7FC; Jamie Smyth, Australia Probes Impact of Facebook and Google on Media, FIN.

TIMES (Dec. 3, 2017), https://perma.cc/Z46B-PA6L.

20

. There has been push-back on the idea that network effects and econo-

mies of scale can explain market concentration in “big-tech” markets and a

broader conversation about market concentration problems in the United States.

See THOMAS PHILIPPON, THE GREAT REVERSAL 267 (Belknap Press of Harvard

Univ. Press, 2019). But see STIGLER COMMITTEE REPORT, supra note 18 (discussing

in broad terms tendency for digital platforms to concentrate markets due to net-

work effects and other factors); Lina M. Khan, The Separation of Platforms and Com-

merce, 119 COLUM. L. REV. 973 (2019) (observing generally that digital platforms

may tend to tip to monopolies and how network effects can act as a barrier to

entry).

21

. Competition laws in the U.S. and globally prohibit firms with market

power from engaging in conduct that is exclusionary. In the U.S., Sections 1 and

2 of the Sherman Act prohibit exclusionary conduct. 15 U.S.C. §§ 1-2 (1890); see

generally Herbert J. Hovenkamp, The Antitrust Standard for Unlawful Exclusionary

Conduct, 1777 FAC. SCHOLARSHIP AT PENN L. 1 (June 2008) (defining exclusionary

conduct as that “reasonably capable of creating, enlarging or prolonging monop-

oly power by impairing the opportunities of rivals,” where such conduct either

does “not benefit consumers at all,” is “unnecessary for the particular consumer

benefits claimed,” or “produce[s] harms disproportionate to benefits”); United

States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 49-50 (D.C. Cir. 2001) (discussing single

firm exclusionary conduct in technologically dynamic markets). In Europe, Arti-

cle 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) similarly

prohibits firms from using their dominant position in a market to undermine

competition. See Guidance on Article 102 Enforcement Priorities, 2008 O.J. (C 115)

89. In Australia, Section 46 of the Trade Practices Act of 1974 prohibits a company

“in a position substantially to control a market” from leveraging that position to

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

67

been debating how to spur competition outside the scope of antitrust en-

forcement.

22

Some have advocated for the creation of a specialized digital

competition authority, while others have argued more generally for

structural separations.

23

This Article studies the structure of online advertising markets, what

drives competition, and how Google became dominant by engaging in

conduct that lawmakers prohibit in other electronic trading markets. To

“fix” competition in advertising, policymakers might lean on the toolbox

exclude competition. Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) s 46 (Austl.). In China, Arti-

cle 6 of China’s Anti-Monopoly Law prohibits dominant firms from leveraging

their position to “eliminate or restrict competition.” Fàn Lǒngduàn Fǎ (反垄断法

) [Anti-Monopoly Law of China] (promulgated by the Standing Comm. Nat’l

People’s Cong., Aug. 30, 2007, effective Aug. 1, 2008), art. 6.

22

. STIGLER COMMITTEE REPORT, supra note 18 (proposing interoperability,

stronger merger guidelines and antitrust enforcement, data remedies, and pro-

consumer default rules, amongst others); STIGLER CTR., PROTECTING JOURNALISM

IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL PLATFORMS (2019), https://perma.cc/9LPT-

AQB4 (proposing public funding of news operations, and a requirement that

Google and other digital companies prioritize content according to criteria other

than ad revenue, amongst other measures); CMA FINAL REPORT, supra note 7

(considering regulating dominant digital platforms with a code of conduct);

Madhumita Murgia & Kate Beioley, UK to Create Regulator to Police Big Tech Com-

panies, FIN. TIMES (Dec. 18, 2019), https://perma.cc/DE8S-EXYM (reporting that

the UK in 2020 will move forward with establishing a new tech regulator for

companies such as Google and Facebook); RICHARD KRAMER, CMA ONLINE

PLATFORMS REVIEW: ARETE RESEARCH’S VIEW (2019), https://perma.cc/2F7J-W4LM

(drawing parallels between permitted conduct in advertising markets and pro-

hibited conduct in financial markets). See JASON FURMAN ET AL., UNLOCKING

DIGITAL COMPETITION: REPORT OF THE DIGITAL COMPETITION EXPERT PANEL (2019);

JACQUES CRÉMER ET AL., COMPETITION POLICY FOR THE DIGITAL ERA (Eur. Comm’n

ed., 2019).

23

. See generally supra note 19; Khan, supra note 20 (arguing that lawmakers

should consider prohibiting dominant “digital platforms” from both running a

market and participating in it and that structural separations would be more de-

sirable than non-discrimination rules that would require case-by-case adjudica-

tion); Elizabeth Warren, Here’s How We Can Break Up Big Tech, MEDIUM (Mar. 8,

2019), https://perma.cc/2SYT-T7TX (proposing separating platforms and plat-

form participants and/or fair and non-discriminatory rules of dealing).

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

68

that financial regulators have already developed to protect the integrity

of a parallel real-time trading market, the securities market. That toolbox

provides a framework for understanding and addressing competition

problems in advertising.

Part II begins this conversation by identifying segments of the econ-

omy that have migrated to electronic trading, discussing the structure of

these markets, and explaining how the structure of online advertising

markets, in which Google is dominant, is similar. In markets with this

structure, problems related to concentration and distorted growth can re-

sult when exchanges provide a subset of traders with information or

speed advantages. Problems can also result when trading intermediaries

route orders (i.e., liquidity) to an exchange in a discriminatory manner or

abuse their access to third parties’ sensitive nonpublic information. In the

stock market, lawmakers safeguard competition by requiring exchanges

to give all traders non-discriminatory access to the marketplace, by iden-

tifying and managing intermediary conflicts of interest, and by requiring

trading disclosures to advance both principles. The integrity of the ad-

vertising market does not benefit from parallel competition safeguards.

Part III examines Google’s extensive conflicts of interest and specific

conduct in advertising. Part A first discusses how the story of Google’s

rise is in part a story of information and speed asymmetry: Google’s ex-

change advantages the Google-owned intermediaries with better infor-

mation about the ad space trading on Google’s exchange and with speed

advantages. When it comes to information asymmetries, Google often

weds its practice of cutting off rivals’ access to data in the noble language

of furthering user privacy. But users’ privacy is not protected from

Google, only from trading rivals, and competition is stunted as a result.

Part B then explains how Google routes buy and sell orders in a discrim-

inatory manner, to both its exchange and web properties. Finally, Part C

considers how Google distorts competition by using the sensitive non-

public information belonging to third-party buyers and sellers—infor-

mation it becomes privy to as an intermediary—to inform its own trading

activity in the market.

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

69

Although Google’s conduct may appear novel and unprecedented,

Part IV discusses in more depth how policymakers have dealt with par-

allel conduct in other electronic trading markets. As additional segments

of the economy have migrated to real-time electronic trading, including

small and emerging sectors like event tickets, airfare tickets, and crypto-

currencies, lawmakers have monitored for these common competition

problems, and they have at times intervened with legislation or regula-

tion when market participants have not sufficiently self-regulated their

behavior. Because the advertising sector now trades on electronic ex-

changes too, we might similarly borrow from the principles of financial

regulation—ensuring equal access to speed and information and manag-

ing intermediary conflicts of interest—in order to protect the integrity of

advertising.

II. ELECTRONIC TRADING MARKETS

A. Advertising Market Reflects the Structure of an Electronic Trading

Market

The rise of buying and selling ad space on electronic exchanges par-

alleled a shift to computerized trading systems across various sectors of

the economy. For example, shares of issued stock trade on stock ex-

changes like the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), which once reflected

a hustle and bustle of traders on a physical exchange floor. Though tele-

vision networks like CNBC still perpetuate this image, today, stocks, cur-

rencies, and other financial instruments trade on dozens of electronic

trading venues at the same time and at lighting speed.

24

The NYSE is

24

. For a discussion of how equities trading happens on national public

exchanges, off-exchange alternative trading systems, and internalization plat-

forms, see Merritt Fox et al., The New Stock Market: Sense and Nonsense, 65 DUKE

L.J. 191 (2015); Kevin S. Haeberle, Discrimination Platforms, 42 J. CORP. L. 809

(2017); MATTEO AQUILINA ET AL., QUANTIFYING THE HIGH-FREQUENCY TRADING

“ARMS RACE”: A NEW METHODOLOGY AND ESTIMATES (Fin. Conduct Auth. ed.,

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

70

largely comprised of computer servers, interconnected by colored wiring

in nondescript buildings off the New Jersey Turnpike.

25

To buy and sell on these financial exchanges, investors used to go

through a human middleman. But now brokers and other intermediaries

are also computerized, connecting electronically to exchanges through

application programming interfaces. An individual investor might use

an online interface belonging to a broker like E*Trade, while an institu-

tional trader might use sophisticated algorithms to trade at high speeds

in an automated fashion.

Outside of tradeable financial assets like equities, the tickets for

sports, theater, and music events now trade on electronic marketplaces

and “exchanges,” as do emerging cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and

Ether.

26

To buy and sell on these electronic trading venues, one can use

an online interface or go through a “broker.” Here too, trading strategies

can make use of computerized algorithms to buy and sell in an auto-

mated way at high speeds.

The biggest financial players have been helping to propel electronic

trading to new sectors of the economy. For example, the parent company

of the NYSE, Intercontinental Exchange, recently made a takeover bid for

eBay (withdrawn), which, until not long ago, also owned the largest

event ticket marketplace, StubHub.

27

Separately, large financial brokers,

2020); SCOTT PATTERSON, DARK POOLS: THE RISE OF THE MACHINE TRADERS AND

THE RIGGING OF THE U.S. STOCK MARKET (Crown Bus. ed., 2013).

25

. Graham Bowley, The New Speed of Money, Reshaping Markets, N.Y. TIMES

(Jan. 1, 2011), https://perma.cc/4VEB-F987.

26

. Note, tickets trade in primary and secondary markets. See generally U.S.

GOV’T ACCOUNTABILITY OFF., GAO-19-347, EVENT TICKET SALES: MARKET

CHARACTERISTICS AND CONSUMER PROTECTION ISSUES (2018); ERIC T.

SCHNEIDERMAN, OBSTRUCTED VIEW: WHAT’S BLOCKING NEW YORKERS FROM

GETTING TICKETS (N.Y. State O.A.G. ed., 2016); BARBARA UNDERWOOD, VIRTUAL

MARKETS INTEGRITY INITIATIVE REPORT (N.Y. State O.A.G. ed., 2018) (providing an

overview of cryptocurrency trading).

27

. Cara Lombardo & Corrie Driebusch, NYSE Owner Intercontinental Ex-

change Makes Takeover Offer for EBay, WALL ST. J. (Feb. 4, 2020),

https://perma.cc/79DL-SW38.

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

71

including E*Trade and TD Ameritrade, are launching cryptocurrency ex-

changes and trading desks.

28

NYSE rival, Nasdaq, has taken a different

approach, licensing its underlying marketplace technology to jumpstart

other sectors’ migration to electronic trading.

29

One exchange built on the

Nasdaq framework is NYIAX, the New York Interactive Advertising Ex-

change.

30

But the biggest names in the advertising market are not NYSE or

Nasdaq; they are Google and Facebook. These companies, amongst the

largest market cap companies today, operate the nuts and bolts of what

is likely the most sophisticated of all electronic trading markets: online

advertising. Whereas the world’s largest financial exchange, the NYSE,

trades the shares of a few thousand companies and processes a few bil-

lion shares a day, Google’s advertising exchange trades ad spaces tar-

geted to billions of individual users and likely processes tens of billions

of these targeted ad spaces daily.

31

Just as individual investors go through an intermediary broker to

trade on financial exchanges, publishers and advertisers must also go

through a computerized middleman to trade on advertising exchanges.

On the buy-side, advertisers use specialized software made either for

small or large advertisers. Smaller advertisers, such as your local dry

28

. Elizabeth Dilts, TD Ameritrade Invests in Cryptocurrency Exchange ErisX,

REUTERS (Oct. 3, 2018), https://perma.cc/KPE7-RZEL; Julie Verhage, E*Trade Is

Close to Launching Cryptocurrency Trading, BLOOMBERG (Apr. 26, 2019),

https://perma.cc/SE4K-H888.

29

. Non-Traditional Exchanges & New Markets, NASDAQ,

https://perma.cc/F4TN-N4DM (last visited Sept. 29, 2020).

30

. Announcing NYIAX, the World’s First Advertising Contract Exchange,

NASDAQ (Mar. 14, 2017), https://perma.cc/8UZT-FDS7.

31

. Jeff Desjardins, Here’s the Difference Between the NASDAQ and NYSE,

BUS. INSIDER (July 11, 2017), https://perma.cc/L6YQ-BF77; Markets Diary, WALL ST.

J.: MKTS., https://perma.cc/F7SV-LTQC (last visited Sept. 29, 2020) (reporting

NYSE daily trading volume); Chiradeep BasuMallick, What Is an Ad Exchange?

Definition, Functioning, Types, and Examples, TOOLBOX: MKTG. (May 18, 2020),

https://perma.cc/9AW7-SN9G (estimating that advertising exchanges process

approximately 70 billion ad “impressions” (i.e., ad spaces) daily).

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

72

cleaner, might use a simple, self-serve online buying tool, such as Google

Ads, which Google has analogized to the “online broker” in the ad mar-

ket.

32

Continuing this analogy, an early Google Ads competitor called it-

self “the eTrade to Google’s NYSE.”

33

In practical terms, the dry cleaner

sets a budget and defines its bid parameters (e.g., bid ceiling) and Google

Ads will bid on and buy ad space, including those trading on Google’s

exchange, in an automated fashion on the dry cleaner’s behalf.

34

How-

ever, Google here can ultimately be the advertiser’s counterparty, not its

agent.

Larger advertisers like Proctor and Gamble use enterprise trading

software that the industry calls demand side platforms (DSPs) and, again

32

. Comparisons between the advertising market and the financial market

have frequently been made by advertising industry participants, including

Google and others. For instance, Google compared Google Ads (then called Ad-

Words) to an online broker: “Who participates in the Ad Exchange? Again, im-

agine the Ad Exchange as a stock exchange. Only the largest brokerage houses

actually plug into, say, the NYSE. In the Ad Exchange world, those are: The large

online publishers (sellers)—websites like portals, entertainment sites and news

sites Ad networks and agency holding companies that operate networks (buy-

ers)—companies that connect web sites with advertisers.” The DoubleClick Ad Ex-

change, GOOGLE, https://perma.cc/5TTF-7PEK (last visited Oct. 3, 2020); see also

Mansour et al., supra note 4 (analogizing “like financial exchanges that only let

licensed brokers trade, ad exchanges let ad networks trade on the exchange on

behalf of individual advertisers.”).

33

. AdExchanger Staff, On DoubleClick Ad Exchange: More Digital Media In-

dustry Reaction, ADEXCHANGER (Sept. 22, 2009), https://perma.cc/75GY-D87J

(comments of then-CEO of buying tool AdReady).

34

. Note, historically, Google Ads only routed bids to Google’s exchange.

This changed in 2016 when Google Ads started routing bids to non-Google ex-

changes.See DoubleClick Ad Exchange, DOUBLECLICK BY GOOGLE,

https://perma.cc/TZ6F-S55S (last visited Oct. 3, 2020) (explaining that Google’s

exchange is “the only exchange offering access to the full demand of Google Ad-

Words”); Michel Van Luijtelaar, AdWords Remarketing Cross-Exchange, UP

ANALYTICS (Aug. 26, 2016), https://perma.cc/34GY-WJ2P (reflecting that Google

Ads/AdWords started routing bids to non-Google exchanges in May of 2016);

Google Ads Help, About Cross-Exchange for Display Remarketing Campaigns,

GOOGLE, https://perma.cc/NDP3-TDUE (last visited Sept. 29, 2020).

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

73

borrowing from finance, “trading desks.”

35

Compared to the self-serve

software used by smaller advertisers, these software tools provide more

sophisticated bidding algorithms, offer a wider array of user targeting

options, and typically require a higher monthly spending commitment.

36

For brevity, this Article refers to self-serve tools for small businesses,

DSPs, and trading desks, collectively, as “buying tools.”

35

. See generally Michael Sweeney, The Anatomy of a Demand-Side Platform

(DSP), CLEARCODE, https://perma.cc/K9EQ-XKBH. Note, demand side platforms

and trading desks also connect to the ad serving tool used by marketers. See gen-

erally Arvind Kesh, What Is a Demand-Side Platform and How to Choose One,

ADBEAT, https://perma.cc/K86U-J2UK.

36

. See generally Kesh, supra note 35 (summarizing that most DSPs require

monthly spend commitments of $5,000-$10,000 U.S. dollars).

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

74

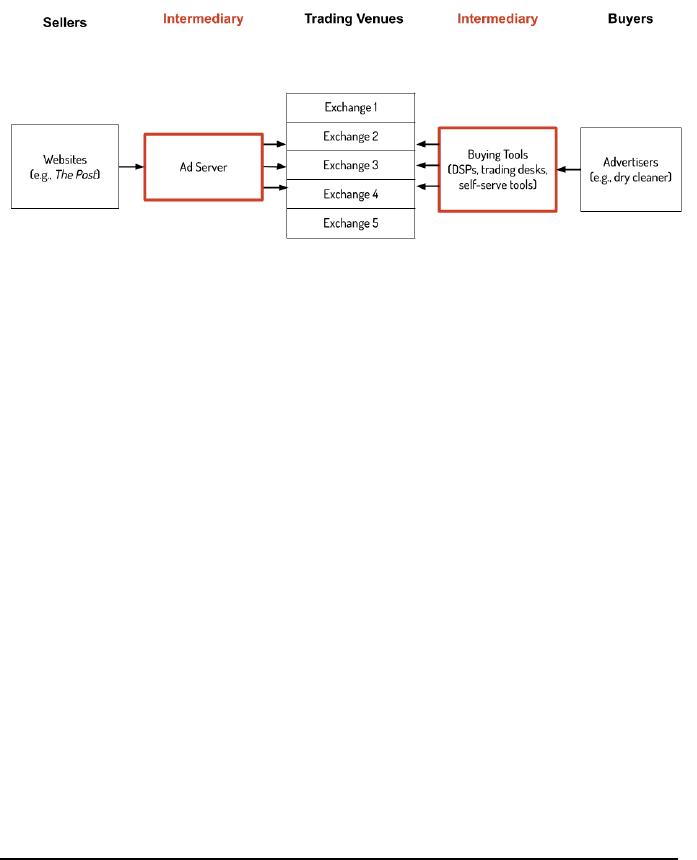

Figure 1: The Buy-Side Intermediaries: Buying Tools*

*Advertisers must use buying tools to access the exchanges where ads

are bought and sold.

The counterparts of advertisers in this market are those selling ad

space, including publishers such as The Post and The Register. Sellers use

a different type of computerized intermediary called an “ad server” to

sell their inventory on exchanges.

37

At a simple level, the ad server is in-

ventory management software, which keeps track of the number of ad

spaces a publisher has available to sell and houses sensitive information

about the publisher’s campaigns, advertisers, and pricing.

38

As a part of

37

. It is worth noting that Google recently blurred the distinction between

its ad server and exchange by both reclassifying its ad serving revenues in its

shareholder reports and merging the two into a new single product renamed

Google Ad Manager (GAM). Jonathan Bellack, Introducing Google Ad Manager,

GOOGLE: AD MANAGER (June 27, 2018), https://perma.cc/T3HN-YCZV (announc-

ing that Google has merged its ad server and exchange together and renamed

them Google Ad Manager). However, from 2008 through 2018, Google’s ad

server and exchange were marketed as separate, distinct, products. Additionally,

in every 10K SEC filing from 2008 (the year Google acquired DoubleClick)

through 2014, Google distinguished its “ad serving software” from its exchange

and ad network. It was only in 2015 that Google reclassified its ad serving soft-

ware revenues from “other” to “advertising revenues” and stopped referring to

its ad server as a separate product. See Google Inc. (2008-2015), supra note 10.

38

. NetGravity Launches AdServer, the Premier Advertising Management Sys-

tem Software for World Wide Web Publishers, NETGRAVITY (Jan. 31, 1996),

https://perma.cc/7B2W-JB4M (announcing launch of first “adserver”); Julia

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

75

this role, the ad server also acts as a link between a publisher’s inventory

and real-time trading venues, routing ad space to exchanges in real-time

as they become available for sale.

39

After a publisher sells its ad space,

information about the order goes into the ad server. The ad server then

tracks these orders and ensures each advertiser’s ads are displayed (i.e.,

are served) in the right spot, at the right time, to the right users.

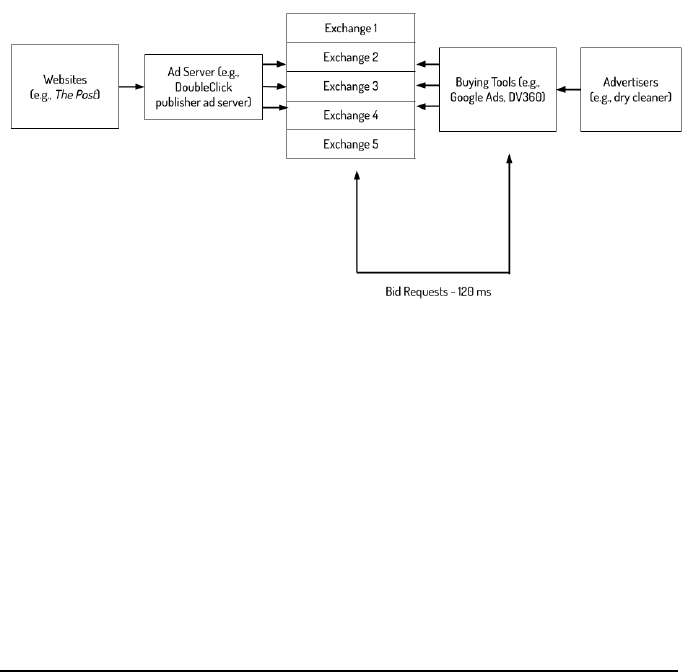

Figure 2: The Sell-Side Intermediary: Ad Server*

Brockhoff et al., Google/DoubleClick: The First Test for the Commission’s Non-Hori-

zontal Merger Guidelines, 2 COMPETITION POL’Y NEWSL. (Eur. Comm’n Competi-

tion), 2008, at 53 (explaining the core functions of an ad server); DoubleClick Inc.

and Compaq Computer Corp., Advertising Services Agreement, FINDLAW (Jan. 18,

1999), https://perma.cc/5T83-RGJ3 (detailing commercial terms of an old Dou-

bleClick license).

39

. Specifically, when a user loads a publisher’s webpage, the user loads

the ad server’s “tag,” which is commonly Google’s since Google owns the lead-

ing ad server in the market. Historically, Google’s ad server limited interconnec-

tion with non-Google exchanges. See infra Part III.B. When this was the case,

Google’s ad server redirected the user’s browser to call non-Google exchanges

directly. See How RTB Ad Serving Works, AD OPS INSIDER (Dec. 15, 2010),

https://perma.cc/S3TR-T84E (discussing how it worked historically). This process

changed in part when Google’s ad server introduced a product enhancement

called Open Bidding. With Open Bidding, it is Google’s ad server (and not the

user’s browser) that makes direct calls to integrated exchanges. See Jonathan Bel-

lack, Improving Yield, Speed and Control with DoubleClick for Publishers First Look

and Exchange Bidding, GOOGLE AD MANAGER (Apr. 13, 2016),

https://perma.cc/LMU4-ENCQ.

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

76

*Websites must use an ad server to access the exchanges where ads are

bought and sold.

The lifecycle of an ad trade flows through these three software com-

ponents—the ad server, the exchanges, and the buying tools—and begins

the moment a user visits a webpage.

40

The user’s visit triggers the pub-

lisher’s ad server to identify the user loading the page and to route the ad

space on that page to one or more exchanges. The exchange then sends

trading signals called “bid requests” to the buying tools that have a “seat”

to bid, soliciting them to return a bid for that space without knowing

what others are simultaneously returning as their bid.

41

Each exchange

then holds an auction, picks a winning bid, and returns it to the ad server.

The ad server can then maximize the publisher’s inventory yield by se-

lecting the advertisement associated with the highest exchange bid and

returning it to the user’s page all before it finishes loading.

40

. Websites might use another software called a supply side platform

(SSP) between their ad server and exchanges. The SSP’s job is to route the site’s

ads to exchanges in a way that maximizes yield. However, the ability today to

route ad space to multiple exchanges synchronously largely renders SSPs obso-

lete, which is why the delineation between SSPs and exchanges has largely dis-

appeared. See Maciej Zawadziński & Michal Wlosik, What is a Supply-Side Plat-

form (SSP) and How Does It Work?, CLEARCODE (Oct. 18, 2018),

https://perma.cc/F5TG-UKVA (explaining what an SSP is and does); Ryan Joe,

Defining SSPs, Ad Exchanges and Rubicon Project, ADEXCHANGER (Feb. 7, 2014),

https://perma.cc/FQP2-JA8Q (describing the disappearing delineation between

SSPs and exchanges).

41

. See generally Verizon Media, Auction Mechanics 101, VERIZON (Jan. 30,

2019), https://perma.cc/53XX-CAQU (explaining how advertising auctions

work); Authorized Buyers Real-Time Bidding Proto, GOOGLE,

https://perma.cc/YKE6-N6DX (explaining how Google shares advertisers’ bids

post auction conclusion).

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

77

Figure 3: Electronic Ad Trading Altogether

B. Common Competition Problems in Electronic Trading Markets

In the online advertising market, as well as in other electronic trading

markets, access to information, speed, and the routing of buy and sell

orders are the linchpin of a healthy, competitive market. Access to infor-

mation about what is trading on an exchange is critical to those compet-

ing to buy on the same venue. In advertising, the bid requests that ex-

changes send to buying tools contain important information used to

decide whether and how much to bid for an ad. This includes the size of

the ad space for sale (e.g., 300x250 pixels), the page address (e.g., ny-

times.com/HowToDoLaundry), and some information about the identity

of the user.

42

Importantly, when these bid requests do not contain suffi-

cient information about the identity of the user loading the page, which

people in the industry have called the “skeleton key” of programmatic

42

. For a list of what Google includes in bid requests, see Google Develop-

ers, Real-Time Bidding: Example Bid Request, GOOGLE, https://perma.cc/X4ND-

77V9 (last visited Oct. 4, 2020). For an example of what another major exchange

includes in bid requests, see Xandr Bidders, Open RTB 2.0 Bid Request, XANDR,

https://perma.cc/AW5X-ST22 (last visited Sept. 29, 2020), which explains bid re-

quests and the fact that they contain “all the necessary information for a bidder

to produce a bid price.”

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

78

advertising, the buying tools bidding on behalf of advertisers sit out of

auctions or bid significantly less.

43

Speed is critical to electronic trading, whether on advertising, stock,

ticket, or cryptocurrency exchanges.

44

Online ad space trades in the mil-

liseconds that it takes for users’ pages to load and exchanges and buying

tools communicate with each other at lightning speed. When an adver-

tising exchange sends out bid requests, it sets the time each buying tool

has to respond with a bid. Within this timeframe, which is usually be-

tween 100 to 160 milliseconds (one to two-tenths of a second), each tool

races to unpack the data contained in the bid request, query additional

user data (e.g., this particular user’s spending habits), determine what

price to bid, and return a bid back to the exchange before time is up.

45

43

. Andrew Casale, Identity: Programmatic’s Skeleton Key, VIMEO, at 5:40

(May 21, 2018), https://perma.cc/E28F-EXQJ.

44

. See generally FirstPartner, Digital Advertising: The Role of Cloud and Con-

nectivity in Ad Trading and Delivery, INTERXION (2020), https://perma.cc/67ZR-

QTUT (explaining that “very fast response times” are “a precondition for com-

peting” and “[t]rading and delivering ads at very high speed is a critical require-

ment, and depends on rapid interactions between partner companies”); Hasham,

How Network Latency Affects the RTB Process for AdTech, DATAPATH (Apr. 21, 2016),

https://perma.cc/4W6Q-GUL2 (explaining that a “small improvement in latency

can spell the difference between winning an auction and not being considered

for the auction at all”); Tejaswini Tilak, NEED FOR SPEED: Why the Online Ad

Industry Is Converging on Equinix, EQUINIX (Nov. 18, 2013),

https://perma.cc/G6GE-TV48.

45

. Google Ad Manager, Bring More Bids to the Auction with Open Bidding,

GOOGLE, https://perma.cc/YPH2-KPAL (last visited Sept. 29, 2020) (sharing new

Google ad server Open Bidding timeouts of 160 milliseconds); BidResponse Object,

OPENX (Oct. 9, 2017), https://perma.cc/37ME-6S9E (discussing OpenX exchange

timeouts of 125 milliseconds and how the exchange reduces the number of bid

requests sent to bidders with frequent timeouts); PubMatic Technical Documen-

tation, OpenRTB 2.1 API Performance, PUBMATIC, https://perma.cc/36BA-42PK

(last visited Sept. 29, 2020) (“PubMatic’s performance requires that the total la-

tency should be within 130 milliseconds - 30 ms for connection establishment and

100 ms for bid response. If either of these independent thresholds are exceeded

(connection and bid response time) during the transaction the bid is considered

a ‘timeout.’”).

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

79

After the set time, the exchange closes the auction, excludes the bids that

arrived too late, and chooses a winner.

Across any of these electronically traded markets, an exchange can

distort competition between the different buyers competing in its mar-

ketplace by giving some an information or speed advantage. In advertis-

ing, an exchange might give some buying tools (bidders) superior infor-

mation about the ad space (e.g., the user’s identity) or let some colocate.

Colocation, which is also central to equities trading, broadly refers to the

practice of placing trading computers and exchange computers close to-

gether to reduce the time it takes for signals to travel between the two.

46

By colocating with an ad exchange, a bidder can receive and respond to

bid requests faster than the bidders that are not colocated, allowing it to

be included more often in exchanges that subject their auctions to strict

time constraints.

Just as exchanges can distort competition between bidders, the trad-

ing intermediaries can distort competition between exchanges by the way

that they route buy and sell orders to exchanges. When ad space on a site

becomes available for sale, the ad server—like the broker in financial

markets—determines whether to route that space only into Exchange A,

or Exchange A, B, and C, on equal terms, and whether to do so at the

same time. Similarly, when an advertiser uses a buying tool to bid on and

buy ad space from exchanges, this intermediary determines whether to

route the advertiser’s bids only into Exchange A, or Exchange A, B, and

C, on equal terms. A company that operates an intermediary, especially

one that has significant market share and enjoys barriers to entry, can

distort competition in the exchange market by, for example, preferen-

tially routing buy and sell orders to a particular trading venue.

46

. Geoffrey Rogow, Colocation: The Root of All High-Frequency Trading

Evil?, WALL ST. J. (Sept. 20, 2012), https://perma.cc/QM7B-HSA3 (defining colo-

cation); Google Ad Manager Help, How Google Ads and Display & Video 360 Work

with Ad Exchange, GOOGLE, https://perma.cc/MWY3-JLP5 (last visited Sept. 26,

2020) (discussing speed and other advantages of colocation).

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

80

Also critical to competition is the way that trading intermediaries

handle the material nonpublic information belonging to third party buy-

ers and sellers. Problems often arise when companies trade on behalf of

third parties, but also trade on behalf of themselves. For example, in fi-

nancial markets, a broker might receive a Carl Icahn sell order for 10 mil-

lion shares of Tesla. The broker can best serve Icahn’s interests by keeping

information about his trading activity confidential, or alternatively, the

broker can use that information to advance its own interests. For instance,

its proprietary trading division might use information about Icahn’s

trade to get rid of its Tesla shares before information about Icahn’s trade

becomes public and the price of those shares drops. To be discussed more

in Part III, information use problems also arise in advertising markets

when a company both handles trading activity for third parties but also

buys and sells in the market for its own financial interests.

C. The Competition Principles We Apply in the Equities Trading

Market

In the U.S. and globally, lawmakers manage these common electronic

trading issues in the stock market through the application of a handful of

broad principles.

47

While financial market regulation may sound intimi-

dating, the basic principles are straightforward. One guiding principle is

that exchanges must provide traders with fair access to the marketplace,

including access to the data transmitted by exchanges as well as the speed

at which data signals travel from exchanges to traders.

48

When exchanges

47

. U.S. Congress started regulating the stock market in 1934 to prohibit

unfair trading practices and “insure the maintenance of fair and honest markets.”

Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. § 78b.

48

. In the U.S., stock exchanges must obtain approval for their trading

rules from the SEC, who in turn must ensure “fair competition among brokers

and dealers.” 15 U.S.C. § 78k-1(a)(1)(C)(ii). Specific fair access rules are articu-

lated in federal statutes. For example, Rule 610(a) and Rule 603(a)(2) of SEC Reg-

ulation NMS, prohibit the regulated National Market System (NMS) exchanges,

including the NYSE and Nasdaq, from restricting efficient exchange access; these

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

81

permit colocation, terms must be transparent, pricing non-discrimina-

tory, and the length of fiber-optic cord connecting the exchange engine to

the trader servers the same length.

49

Even an extra foot of cabling in a

colocation facility can systemically disadvantage some traders due to la-

tency.

Competition is also protected through the identification and manage-

ment of intermediary conflicts of interest.

50

One principle applied here is

rules also require exchanges to distribute information with respect to quotations

or transactions in a manner “fair and reasonable” or “not unreasonably discrim-

inatory.” See respectively 17 C.F.R. § 242.610(a) (2020) (prohibiting restrictions on

“efficient access”); 17 C.F.R. § 242.603(a)(2) (2020). The SEC has interpreted these

fair access rules to prohibit an exchange from sending data to some traders before

the exchange sends the same data to consolidated feeds. See, e.g., N.Y. Stock Exch.

LLC, Release No. 67857 SEC, 2 (Sept. 14, 2012). While the non-NMS exchanges—

the Alternative Trading Systems (ATSs)—are generally not subject to fair access

rules, some are subject to the fair access standards of Regulation ATS. 17 C.F.R.

§ 242.301 (2020). In the European Union, access to regulated markets (RMs) and

multilateral trading facilities must be transparent and non-discriminatory. Other

jurisdictions globally also require trading venues to provide traders with fair ac-

cess. See generally INT’L ORG. OF SECURITIES COMM’NS [IOSCO], REGULATORY ISSUES

RAISED BY CHANGES IN MARKET STRUCTURES CONSULTATION REPORT 9 (2013) [here-

inafter IOSCO MARKET STRUCTURE CONSULTATION REPORT].

49

. Exchange colocation procedures need to be submitted to and approved

by the SEC. For transparency around exchange colocation services, see, e.g., NYSE

Price List 2020, N.Y.S.E. 28-39 (2020), https://perma.cc/T2XU-HFDF; MORGAN

HAUSEL, THE BAD SIDE OF A GOOD IDEA (Collaborative Fund ed., 2016),

https://perma.cc/AX7A-M6V6 (“NYSE measured the distance to the furthest cab-

inet, which is where people put their servers. It was 185 yards. So they gave every

[high-frequency trader] a cable of 185 yards.”)

50

. See generally Resolution on IOSCO Objectives and Principles of Securi-

ties Regulation and Methodology for Assessing Implementation of the IOSCO

Objectives and Principles of Securities Regulation, Presidents Comm. of the Int’l

Org. of Securities Comm’ns [IOSCO] (May 2017), https://perma.cc/UG65-KS23

(summarizing that one key role of the securities regulator, or an industry self-

regulatory organization, is to avoid, eliminate, disclose, or otherwise manage

conflicts of interest); Carlo V. di Florio, Conflicts of Interest and Risk Governance,

S.E.C. (Oct. 22, 2012), https://perma.cc/L3RW-NY9W (providing an overview of

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

82

a structural one: a company that runs an exchange like the NYSE cannot

also operate a division involved in trading.

51

However, when companies

are permitted to participate in the market in more ways than one, conflicts

of interest and disclosure rules kick in. For example, intermediary broker

dealers can have conflicts: they trade in the market on behalf of third par-

ties (the broker designation), as well as on behalf of themselves as a pro-

prietary trader (the dealer designation), and they can even run a special-

ized trading venue called an Alternative Trading System (ATS).

52

But

these multi-service firms must manage their conflicts of interest and can-

not simply route their customers’ buy and sell orders (order flow) to the

firm’s electronic trading venue.

53

the importance of conflicts of interest management to securities regulation and

the interplay between the existence of conflicts and increased market risk); Chris-

toph Kumpan & Patrick C. Leyens, Conflicts of Interest of Financial Intermediaries -

Towards a Global Common Core in Conflicts of Interest Regulation, 4 EUR. CO. AND

FIN. L. REV. 72 (2008) (defining a conflict of interest as arising when “a person

who has a duty to act in another party’s interest has to decide how to act in the

interest of that party and another interest interferes with his ability to decide ac-

cording to his duty.”).

51

. Conversations with securities professionals indicate that the SEC en-

forces this structural separation through its power to reject public exchange ap-

plications.

52

. Prop. Regulation of NMS Stock Alternative Trading Systems, 80 Fed.

Reg. 80,998 (Dec. 28, 2015) (codified at 17 CFR § 240.3a1-1(a)) (stating that broker

dealers operate ATSs).

53

. It is the Best Execution Rule, grounded in common law principles of

agency, industry self-regulation, and federal securities law, that prohibits de-

facto preferencing or internalization and requires broker dealers to use reasona-

ble diligence in determining where to route client orders. The rule’s application

in equities, however, is not uncontroversial and has application challenges (e.g.,

When does speed of execution trump best price? Is it unrealistic to apply such a

rule to individual trades?). See Jonathan Macey & Maureen O’Hara, The Law and

Economics of Best Execution, 6 J. OF FIN. INTERMEDIATION 188, 188-223 (1997). See

also Paul G. Mahoney & Gabriel V. Rauterberg, The Regulation of Trading Markets:

A Survey and Evaluation, in SECURITIES MARKET ISSUES FOR THE 21ST CENTURY, 221,

221-81 (Merritt B. Fox et al. ed., 2018).

Fall 2020 WHY GOOGLE DOMINATES ADVERTISING MARKETS

83

Competition in the stock market—heavily shaped by access to data

and information—also benefits from rules that regulate who may use

what information when trading. For example, we require financial inter-

mediaries (i.e., brokers and investment advisors) to act in the best interest

of their customers, which forcibly vests property rights in customers’ in-

formation in customers themselves.

54

Brokers, therefore, cannot use in-

formation about their customers’ trading activity to trade in the market

for their own financial gain.

55

This prohibition is further enforced through

54

. Regulation Best Interest under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 re-

quires broker dealers to act in the “best interest” of their customers and not place

their own interest ahead of retail investors when advising on securities or invest-

ment strategy. This code of conduct requires broker dealers to mitigate or elimi-

nate certain some conflicts of interest and disclose others. It also requires broker

dealers to exercise reasonable diligence, care and skill when advising retail cli-

ents. Sec. Exch. Act of 1934, 17 CFR § 240.15l-1(a)(2) (2019). Investment advisors,

on the other hand, owe their customers a fiduciary duty, under the Investment

Advisors Act of 1940, 17 CFR § 275 (1940). The SEC has interpreted this duty to

permit investment advisors to sometimes merely disclose some types of conflicts

to institutional clients; to retail customers, investment advisors may instead have

to mitigate or eliminate conflicts entirely, especially complex ones. The fiduciary

standard for investment advisors also includes an ongoing duty to monitor cus-

tomer accounts. As background, per the Dodd-Frank Act, Dodd-Frank Wall

Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111-203, § 929-Z, 124

Stat. 1376, 1871 (2010) (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 78o), the SEC was to “harmonize”

the duties of broker dealers and investment advisors. When promulgating a “best

interest” rule, as opposed to a parallel fiduciary rule, seven states, the District of

Columbia, and others, filed suit, challenging the short falling of the “best inter-

est” rule. Keith Blackman et al., Second Circuit Upholds Regulation BI, NAT’L L. REV.

(July 3, 2020), https://perma.cc/B8CY-D4TV.

55

. If a broker uses information about a customer’s trading activity to place

and execute trades in advance of the customer’s, it is called trading ahead or front

running, and is prohibited under common law principles of agency (which the

law constructs regardless of contractual intentions), industry self-regulation, and

federal securities law. See Opper v. Hancock Sec. Corp., 250 F. Supp. 668, 676

(S.D.N.Y. 1966) (holding front running to be illegal under principles of agency

and federal law), aff’d, 367 F.2d 157 (2d Cir. 1966); FINRA Rule 5270, FINRA

Rules, FIN. INDUS. REG. AUTH., https://perma.cc/5WPC-LMEF; NORMAN S. POSER,

STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW Vol. 24:1

84

Congressionally mandated ethical walls—internal corporate policies and

physical barriers that brokers must implement to prevent the flow of sen-

sitive information from one business division (e.g., the broker division)

to another (e.g., the dealer division).

56

On top of this, rules against insider trading further restrict certain

parties from trading upon particular types of information advantages.

The classic example prohibits corporate “insiders” from trading in the

market using material nonpublic information.

57

However, insider trading

BROKER-DEALER LAW AND REGULATION 16-5 (4th ed. 2007) (discussing broker

dealer duties).

56

. In 1988, Congress passed the Insider Trading and Securities Fraud En-

forcement Act of 1988, which increased penalties for insider trading and securi-

ties fraud and required registered brokers and dealers to enforce written policies

and procedures to prevent the misuse of material nonpublic information. See In-

sider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act of 1988, H.R. 5133, 100th

Cong. (1998). In 1990, the SEC clarified and outlined minimum requirements for

broker dealers. Section 204 of the Investment Advisers Act contains a similar re-

quirement for investment advisers. See 15 U.S.C. § 78o(g) (2018); DIVISION OF

MARKET REGULATION U.S. SEC. AND EXCH. COMM’N, BROKER-DEALER POLICIES AND

PROCEDURES DESIGNED TO SEGMENT THE FLOW AND PREVENT THE MISUSE OF

MATERIAL NONPUBLIC INFORMATION (U.S. Sec. and Exch. Comm’n ed., 1990); 15

U.S.C. § 80b-4a; RALPH C. FERRARA, DONNA NAGY & HERBERT THOMAS, FERRARA

ON INSIDER TRADING & THE WALL 9-7-9-12 (2017).

57

. Before the SEC took an active role in defining, expanding, and regulat-

ing “insider trading,” information use when trading was primarily governed by

state common law of fraud. The majority rule there rejected any fiduciary rela-

tionship between corporate insiders and shareholders, which would have trig-

gered a duty to disclose material nonpublic information to shareholders before

trading or to withhold from trading. At the helm of the SEC, Chairman William