224 Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2014, Vol. 24 (4): 224-227

INTRODUCTION

Evaluation of nutritional adequacy of diets can be

performed by various dietary data collection techniques.

Currently, such collection techniques include interviewer-

administered 24 hours recalls, self-administered food

records and food frequency questionnaires (self or

interviewed administered). In a 24-h recall, the inter-

viewer through probing questions ask the respondent to

list detail for the description and amounts of all food and

beverages consumed during the previous day, while

food records require the respondent to provide a written

description of the types and amounts of food eaten. On

the other hand, FFQs provide a list of foods and

respondents are asked how often they eat each item on

the list.

1-3

FFQ can assess dietary intake in a way that is

valid, easy and inexpensive to administer and can be

easily utilized in studies for promoting health and

assessing intake. Validation of these tools enhances

their utility and influence.

Calcium intake has received increased attention in the

last decade because of its role in bone health. With

a pandemic of vitamin-D deficiency (VDD); newer

strategies and recommendations have been put forward

for dietary and supplementation intake of vitamin-D

and calcium. Accurate assessment of calcium is critical

in evaluating bone health risks and addressing calcium

needs helps to optimize bone health by improving

deposition in early adolescents and teenage, maintain-

ing bone density in adults, and minimizing bone loss in

older patients.

There is total paucity of research specially targeting

calcium intake and food source in our population. One of

the reasons is lack of availability of tool for assessing

calcium intake. This study was undertaken with the

aim to develop and validate a FFQ for assessing

macronutrient and calcium intake in adult Pakistani

population.

METHODOLOGY

To develop the list of food items to be used in the FFQ

for assessing the nutrient intake, 24-h dietary recall data

was collected from individuals attending the Aga Khan

University's Laboratory Collection points in various parts

of the city. Based on the results of the 24-hour (h) recalls

and experiences from the authors other work, the list of

foods was developed on the FFQ. This FFQ has 64 food

items which are categorized into 8 food groups. A food

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Validation of a Food Frequency Questionnaire for Assessing

Macronutrient and Calcium Intake in Adult Pakistani Population

Romaina Iqbal

1

, Mohammad Ali Haroon

2

, Farhan Javed Dar

3

, Mujtaba Bilgirami

4

,

Gulshan Bano

1

and Aysha Habib Khan

3

ABSTRACT

Objective: To develop and validate a food frequency table (FFQ) for use in urban Pakistani population.

Study Design: A validation study.

Place and Duration of Study: The Aga Khan University, Karachi, from June to November 2008.

Methodology: Healthy adult females, aged ≥ 18 years who consented to be included in the study were inducted, while

males, unhealthy females, aged below 18 years or who did not consent were excluded. The FFQ was administered once

while 4, 24 hours recalls spread over a period of one year were administered as the reference method. Daily intakes for

energy, protein, fat, and calcium intake were estimated for both the tools. Crude and energy adjusted correlations for

nutrient intakes were computed for the FFQ and mean of 4, 24 hours recalls and serum N-telopeptide of type-I collagen

(NTx).

Results: The correlation coefficients for the FFQ with mean of 4, 24 hours recall ranged from 0.21 for protein to 0.36 for

calcium, while the correlation for nutrient estimates from the FFQ with NTx ranged from -0.07 for calcium to 0.01 for

energy.

Conclusion: Highly significant correlations were found for nutrient intakes estimated from the FFQ vs. those estimated

from the mean of 4, 24 hours recalls but no correlations was found between nutrient estimates from the FFQ and serum

NTx levels. FFQ was concluded to be a valid tool for assessing dietary intake of adult females in Pakistan.

Key Words: Food frequency questionnaire. Females. Macronutrient intake. Calcium. N-telopeptide of type-I collagen. Bone turnover.

1

Departments of Community Health Sciences/ Pathology and

Microbiology

3

/ Family Medicine

4

, The Aga Khan University

Hospital, Karachi.

2

Medical Student, Ziauddin University, Karachi.

Correspondence: Dr. Romaina Iqbal, 82-C, Block 6, PECHS,

Karachi-75400.

E-mail: r[email protected]

Received: March 01, 2012; Accepted: November 22, 2013.

composition table for all the food items on the list was

also being developed so that the dietary intake could be

converted into nutrient estimates. The food frequencies

were reported as never, several times per year, 1 - 3 times/

month, once a week, 2 - 3 times/week, 4 - 6 times/week,

once a day, 2 - 3 times/day and ≥ 4 times/day.

To estimate nutrient intake, the reported intake frequency

of each food on the FFQ was multiplied by reported

portion size and its respective nutrient composition,

summing over all foods. The composition of raw food

items was determined from the USDA.

4

In certain cases

where this information was not available from the USDA,

other local food composition tables were consulted.

5,6

The study was approved by the ERC via 811-Pat/

ERC-07.

Two hundred apparently healthy adult females, aged

≥ 18 years, were recruited through convenient, non-

purposive sampling. Subjects were contacted through

two different approaches. A door-to-door approach was

exercised in community residents in district Karachi

East. AKU hospital employees and their relatives

residing in any part of Karachi were also approached.

Information regarding patients' name, age and ethnicity

was collected by research officer through face-to-face

interviews using a structured questionnaire and para-

meters of weight and height were measured. At this

time, the participants were administered the FFQ and

one 24-hour (h) recall. The interview and blood was

taken after informed consent at a phlebotomy center of

AKU laboratory at Shahra-e-Faisal, Karachi, and main

Clinical laboratory at the Aga Khan University situated in

district East. Furthermore, these participants completed

3, 24-h recalls more, over a period of one year via

telephone calls. Out of the 200 recruited, only 144

provided complete information, consequently our final

sample size for analysis was 144 participants.

Eight milliliters of blood was drawn from the antecubital

vein in the fasting state for biochemical analysis. All

blood samples were centrifuged. Required serum and

plasma stored at -70°C until assayed.

Bone turnover was assessed by measuring N-

telopeptide of type-I collagen (NTx) using an ELISA kit

OsteomarkNTx from Ostex International, Inc., Seattle,

WA. For quality control, low and high controls were run.

Inter-assay and intra-assay variability for serum NTx

assays are 6.9% and 4.6% respectively. Results are

expressed as nanomoles of bone collagen equivalents

per liter of serum (nMBCE/L). The range of serum NTx

levels in healthy females is taken from 6.2 to 19.0

nMBCE/L with a mean of 12.6 nMBCE/L. Serum NTx

levels > 19 nMBCE/L was taken as high bone turnover.

Mean nutrient intakes with their standard deviations

were computed for the FFQ and the mean of the 4,

24-h recalls nutrient estimates. Nutrient estimates were

log transformed as they were skewed positively.

Pearson product -moment correlations between intakes

estimated by the FFQ and those calculated from the

recalls were computed as shown in Table III. The crude

as well as energy adjusted correlations were assessed

for the nutrient estimates between those obtained from

the FFQ versus those taken from the 24-h recalls as well

as NTx, where level of significance was taken to be 0.05

two sided.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 17 was

used for all statistical analysis.

RESULTS

The mean age of the participants was 32.8 ± 11.4 years.

The mean BMI was 23.8 ± 4.8 kg/m

2

, height being 156.5

± 5.4 cm and weight being 58.3 ± 11.3 kg. The mean

NTx level was 19.0 ± 8.7 nMBCE/L and the mean serum

PTH level was 73.7 ± 34.7 pg/ml (Table I). Further

results are shared in Table I.

Intake of energy and macronutrients were similar using

the FFQ and 24-h recalls, but higher for FFQ (Table II).

Mean usual daily energy estimated from the FFQ was

Kcal 1643.5 ± 703.1 kcal; daily protein intake was 55 ±

23.3 g, fat 61.7 ± 29.4 g, and calcium 610.7 ± 306.3 mg.

While the mean usual daily energy intake estimated from

the mean of 4, 24-h recalls was 1391.8 ± 365.3, daily

proteins intake was 45.4 ± 13.9 g, fat 52.0 ± 17.9 g,

calcium 462.1 ± 175.7 mg (Table II).

Comparing mean nutrient estimates from the FFQ with

4, 24-h recalls, the correlation coefficient ranged from

0.21 for protein to 0.36 for calcium, while the correlation

for nutrient estimates from the FFQ with NTx ranged

from -0.07 for calcium to 0.01 for energy. The energy

adjusted correlation between mean nutrient estimates

of FFQ with 4, 24-h recall ranged from 0.03 for protein

to 0.32 for calcium. The energy adjusted correlation

Validation of a food frequency questionnaire for assessing macronutrient and calcium intake in adult in Pakistani population

Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2014, Vol. 24 (4): 224-227

225

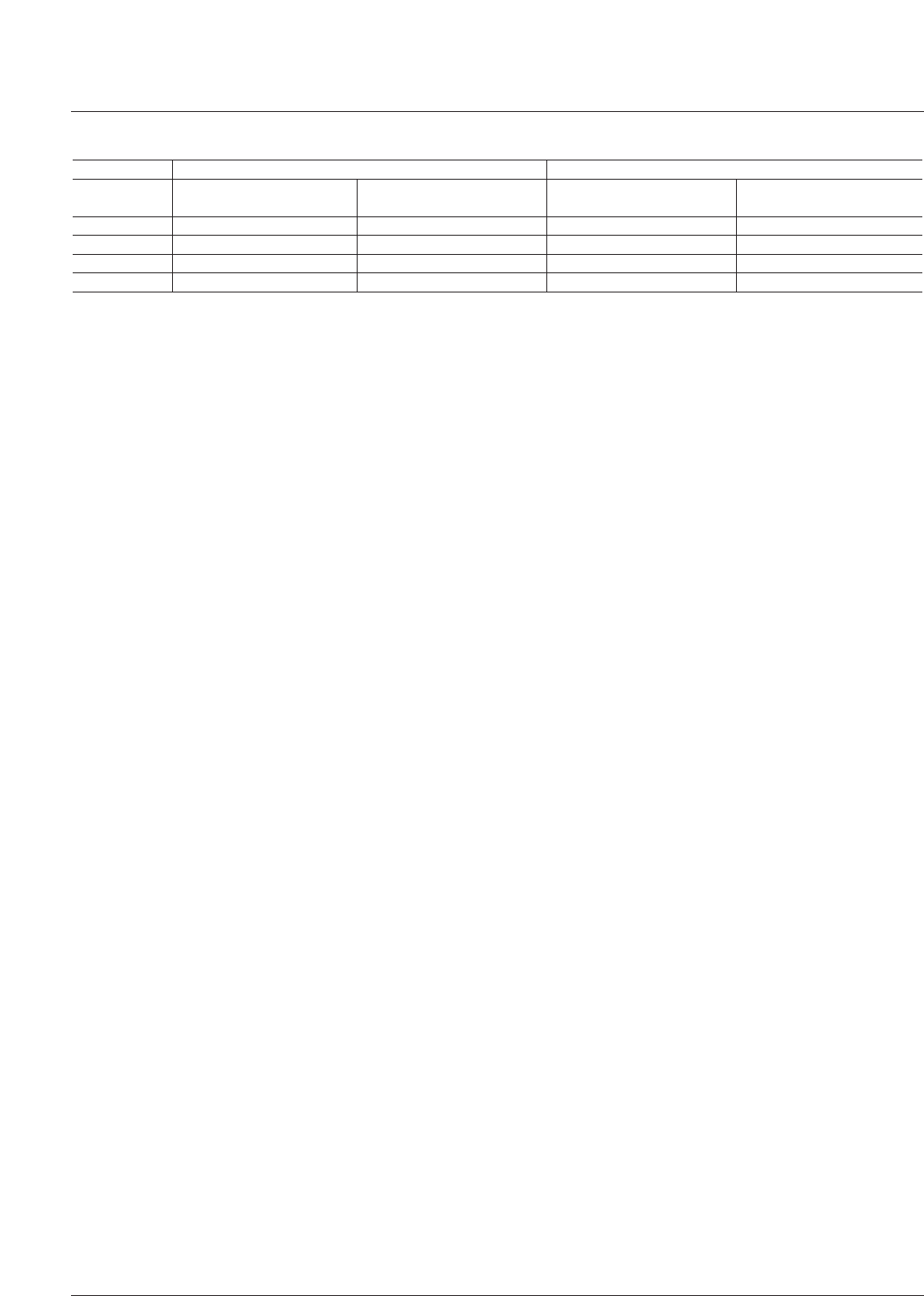

Table I: Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants.

Characteristic Mean SD

Age (year) 32.8 11.4

Height (cm) 156.5 5.4

Weight (kg) 58.3 11.3

BMI 23.8 4.8

NTx (number/L) 19.0 8.7

Serum PTH (pg/ml) 73.7 34.7

SD = Standard Deviation; BMI = Body Mass Index; NTx = N-telopeptide of type-I collagen;

PTH = Parathyroid hormone.

Table II: Mean daily nutrient intakes estimated by the FFQ as the

24-h recalls.

Variables FFQ Mean of 4, 24-h recalls

Mean SD Mean SD

Energy (kcal) 1643.5 703.2 1391.8 365.3

Protein (g) 55.0 23.3 45.4 13.9

Fat (g) 61.7 29.4 51.9 17.9

Calcium (mg) 610.7 306.4 462.1 175.7

FFQ = Food Frequency Questionnaire; SD = Standard Deviation.

between means estimates of FFQ with serum NTx

ranged from -0.02 for fat to 0.03 for energy (Table III).

DISCUSSION

In epidemiological studies of chronic diseases, the

understanding of the usual diet is of sheer importance in

the progression and development of disease, as

compared to the clinical setting where the dietary intake

is titrated as per the requirement of the condition.

7

Epidemiological studies conducted all over the world

employ FFQ as a standard method to acquire a sense of

the day-to-day nutrient consumption of the population. In

this study, the authors have described the development

and validation of a food frequency questionnaire to

assess the dietary intake of adult Pakistani population

residing in Pakistan.

A food composition table was developed, which was

largely based on US Department of Agriculture nutrient

database, to estimate the nutrient intake from the FFQ.

There are several advantages of using the USDA

nutrient data base as the standard. USDA is considered

as the most comprehensive nutrient data base in the

world. The USDA nutrient data base has the largest

number of nutrient reported, and is constantly updated

with the nutrient estimation assays conducted in a

standardized manner. There are over 150 food

composition tables used around globally and their

values are primary derived from USDA.

8-10

Moreover,

comparable methods have been carried out by other

investigators as well.

7,12

However, other local food

composition tables were also consulted where USDA fell

short.

The mean nutrient intake estimated by the FFQ were

similar to those obtained from the 24-h recall and within

the range reported by others in South Asia.

13,14

In an

Indian investigation, mean usual daily energy intake was

observed to be 1749 kcal and 1910 kcal in the urban and

rural population, respectively.

15

Likewise in a study

conducted in South India, the mean daily energy intake

was 2066 ± 437 kcal for men and 1745 ± 343 kcal for

women.

16

Similar to other studies, energy intake

estimated from the FFQ were higher than those obtained

by the 24-h recall.

17

Mean nutrient estimates from the 24-hour recalls were

used as reference method for comparing the nutrient

intakes from the FFQ. The correlations of nutrient

estimates from the FFQ vs. the 24-hour recalls were

highly significant and moderate (0.21-0.36). Adjustment

for energy lowered the correlations. Similar correlations

have also been reported by Huang and Kim.

18,19

This study's correlations of nutrient estimates from the

FFQ with serum NTx levels were extremely low and not

significant. The author was expecting that the intake

estimates from the FFQ and serum NTx would be highly

correlated. This lack of correlation may be due to the

difference in intake of calcium.

20,21

The age of female

participants, bone formation and the presence of other

nutrients and factors that affects bone formation.

22,23

Some limitations of this study merit consideration. The

correlations observed in the present study were in

general lower than those reported by others who

compared FFQ data to several weeks of diet records but

similar to estimates comparing FFQ data to multiple

24-h recalls generally and to studies done in the

subcontinent in particular.

24,25

A possible reason why

this study's correlations are lower than those reported

for FFQ validated against diet records may be that the

data was from only 4, 24-h recalls as a reference

method, as opposed to estimates from several days

considered by others.

25

Another limitation that needs to

be highlighted is that the age groups represented by the

sample are mostly < 50 years, and hence the dietary

intake is skewed toward the younger age group.

Moreover, all the participants were females and hence

the nutrients consumed and the bone turnover of males

may be underestimated. The way to make it more

accurate is to repeat the study, include more participants

from the > 50 age group and male gender.

CONCLUSION

Highly significant correlations were found for nutrient

intakes estimated from the FFQ vs. those estimated

from the mean of 4, 24-hour recalls but no correlations

between nutrient estimates from the FFQ and serum

NTx levels. It was concluded that this FFQ is a valid tool

for assessing dietary intake of adult females in Pakistan.

REFERENCES

1. Moore M, Braid S, Falk B, Klentroul P. Daily calcium intake in

male children and adolescents obtained from the rapid

assessment method and the 24-hour recall method. Nutr J

2007; 6:24.

Romaina Iqbal, Mohammad Ali Haroon, Farhan Javed Dar, Mujtaba Bilgirami, Gulshan Bano and Aysha Habib Khan

226 Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2014, Vol. 24 (4): 224-227

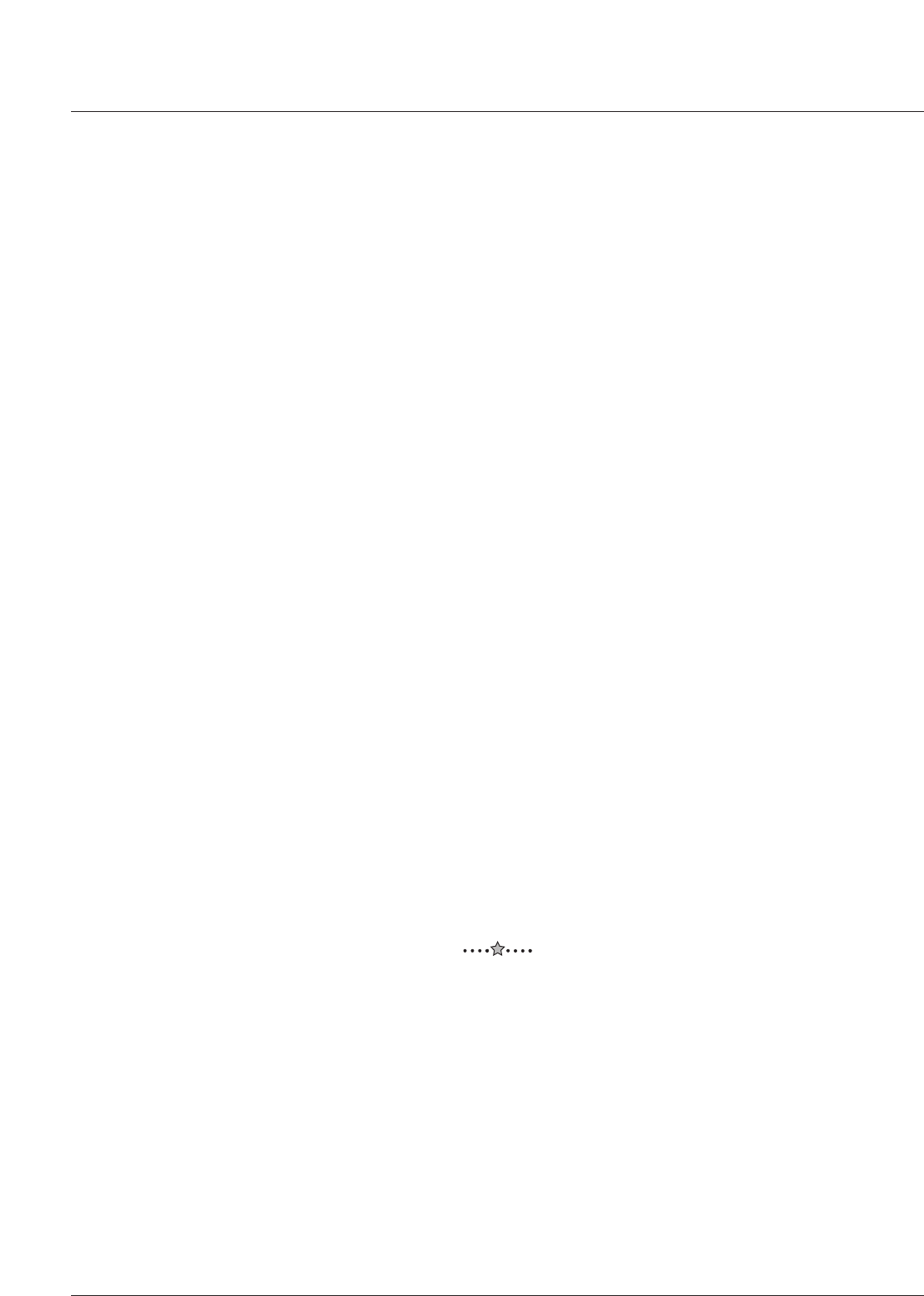

Table III: Crude and energy adjusted correlations between nutrient estimates from FFQ and mean of 4, 24-h recalls and serum NTx values.

Nutrient Mean of 4, 24-h recalls NTx

Crude p-value Energy p-value Crude p-value Energy p-value

adjusted adjusted

Energy 0.248 < 0.001 ----- ----- 0.010 0.912 0.031 0.724

Protein 0.213 0.002 0.029 0.682 -0.002 0.986 0.019 0.831

Fat 0.323 < 0.001 0.116 0.104 -0.043 0.629 -0.019 0.835

Calcium 0.363 < 0.001 0.315 < 0.001 -0.069 0.438 -0.055 0.534

NTx = N-telopeptide of type-I collagen.

2. Guenther PM, Jensen HH, Batres-Marquez SP, Chen CF.

Sociodemographic, knowledge, and attitudinal factors related

to meat consumption in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc

2005; 105:1266-74.

3. Plawecki KL, Evans EM, Mojtahedi MC, McAuley E, Chapman-

Novakofski K. Assessing calcium intake in postmenopausal

women. Prev Chronic Dis 2009; 6:A124.

4. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service.

Nutrient data laboratory [Internet]. 2011. Availabale from:

http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl

5. Judd PA, Khamis TK, Thomas J. The composition and nutrient

content of foods commonly consumed by South Asians in the

U.K. London: Aga Khan Health Board for the UK; 2000.

6. Ministry of Planning and Development, Government of

Pakistan. Food composition table for Pakistan. Islamabad:

Ministry of Planning and Development Government of

Pakistan; 2001.

7. Dehghan M, Al-Hamad N, Yusufali AH, Nusrath F, Yusuf S,

Merchant AT. Development of a semi-quantitative food

frequency questionnaire for use in United Arab Emirates and

Kuwait based on local foods.

Nutr J 2005; 4:18.

8. Aslibekyan S, Campos H, Loucks EB, Linkletter CD, Ordovas

JM, Baylin A. Development of a cardiovascular risk score for

use in low- and middle-income countries. J Nutr 2011; 141:

1375-80.

9. Deharveng G, Charrondière UR, Slimani N, Southgate DA,

Riboli E. Comparison of nutrients in the food composition

tables available in the nine European countries participating in

EPIC. European prospective investigation into cancer and

nutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr 1999; 53:60-79.

10. Garcia V, Rona RJ, Chinn S. Effect of the choice of food

composition table on nutrient estimates: a comparison

between the British and American (Chilean) tables. Public

Health Nutr 2004; 7:577-83.

11. Hakala P, Knuts LR, Vuorinen A, Hammar N, Becker W.

Comparison of nutrient intake data calculated on the basis of

two different databases. Results and experiences from a

Swedish-Finnish study.

Eur J Clin Nutr 2003; 57:1035-44.

12. Shai I, Vardi H, Shahar DR, Azrad AB, Fraser D. Adaptation of

international nutrition databases and data-entry system tools to

a specific population. Public Health Nutr 2003; 6:401-6.

13. Nordin BE. Calcium and osteoporosis.

Nutrition 1997; 13:664-86.

14. Prince RL, Devine A, Dhaliwal SS, Dick IM. Effects of calcium

supplementation on clinical fracture and bone structure: results

of a 5-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in elderly

women. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:869-75.

15. Chadha SL, Gopinath N, Katyal I, Shekhawat S. Dietary profile

of adults in an urban and a rural community. Indian J Med Res

1995; 101:258-67.

16. Shobana R, Snehalatha C, Latha E, Vijay V, Ramachandran A.

Dietary profile of urban south Indians and its relations with

glycaemic status.

Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1998; 42:181-6.

17. Hebert JR, Gupta PC, Bhonsle RB, Murti PR, Mehta H,

Verghese F, et al. Development and testing of a quantitative

food frequency questionnaire for use in Kerala, India. Public

Health Nutr 1998; 1:123-30.

18. Huang YC, Lee MS, Pan WH, Wahlqvist ML. Validation of a

simplified food frequency questionnaire as used in the Nutrition

and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT) for the elderly.

Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011; 20:134-40.

19. Kim SH, Choi HN, Hwang JY, Chang N, Kim WY, Chung HW.

Development and evaluation of a food frequency questionnaire

for Vietnamese female immigrants in Korea: the Korean

Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES). Nutr Res Pract

2011; 5:260-5.

20. Abrams SA. Setting dietary reference intakes with the use of

bioavailability data: calcium.

Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91:1474S-7S.

21. Jarjou LM, Laskey MA, Sawo Y, Goldberg GR, Cole TJ,

Prentice A. Effect of calcium supplementation in pregnancy on

maternal bone outcomes in women with a low calcium intake.

Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92:450-7.Epub 2010 Jun 16.

22. Bonjour JP. Calcium and phosphate: a duet of ions playing for

bone health.

J Am Coll Nutr 2011; 30:438S-48S.

23. Mader R, Verlaan JJ. Bone: exploring factors responsible for

bone formation in DISH. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011; 8:10-2.

24. Shatenstein B, Nadon S, Godin C, Ferland G. Development

and validation of a food frequency questionnaire.

Can J Diet

Pract Res 2005; 66:67-75.

25. Chen Y, Ahsan H, Parvez F, Howe GR. Validity of a food-

frequency questionnaire for a large prospective cohort study in

Bangladesh. Br J Nutr 2004; 92:851-9.

Validation of a food frequency questionnaire for assessing macronutrient and calcium intake in adult in Pakistani population

Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2014, Vol. 24 (4): 224-227

227