RESEARCH & ANALYSIS

Economic Well-Being of

U.S. Households in 2021

May 2022

BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

The Federal Reserve System is the central

bank of the United States. It performs five key

functions to promote the effective operation

of the U.S. economy and, more generally, the

public interest.

The Federal Reserve

■ conducts the nation’s monetary policy to promote maximum employment

and stable prices in the U.S. economy;

■ promotes the stability of the financial system and seeks to minimize

and contain systemic risks through active monitoring and engagement in

the U.S. and abroad;

■ promotes the safety and soundness of individual financial institutions

and monitors their impact on the financial system as a whole;

■ fosters payment and settlement system safety and efficiency through

services to the banking industry and U.S. government that facilitate

U.S.-dollar transactions and payments; and

■ promotes consumer protection and community development through

consumer-focused supervision and examination, research and analysis of

emerging consumer issues and trends, community economic development

activities, and administration of consumer laws and regulations.

To learn more about us, visit www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed.htm.

RESEARCH & ANALYSIS

Economic Well-Being of

U.S. Households in 2021

May 2022

BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

Contents

Executive Summary

......................................................................................................... 1

Overall Financial Well-Being ................................................................................................ 2

Income ............................................................................................................................. 2

Employment ...................................................................................................................... 3

Dealing with Unexpected Expenses ..................................................................................... 3

Banking and Credit ............................................................................................................ 3

Housing ............................................................................................................................ 4

Education .......................................................................................................................... 4

Student Loans ................................................................................................................... 5

Retirement and Investments ............................................................................................... 5

Overall Financial Well-Being

.......................................................................................... 7

Current Financial Situation ................................................................................................. 7

Changes in Financial Situation over Time ........................................................................... 12

Local and National Economic Conditions ............................................................................ 14

Overall Life Satisfaction .................................................................................................... 15

Income

............................................................................................................................. 17

Level and Source ............................................................................................................. 17

Child Tax Credit ................................................................................................................ 19

Income Variability ............................................................................................................. 20

Employment

.................................................................................................................... 23

Reasons for Not Working .................................................................................................. 23

Working from Home .......................................................................................................... 25

Job Changes .................................................................................................................... 28

COVID-19 Precautions at Work .......................................................................................... 29

Part-Time Jobs, Temporary Jobs, and Irregular Schedules .................................................... 31

The Gig Economy ............................................................................................................. 31

Dealing with Unexpected Expenses

........................................................................... 35

Small, Unexpected Expenses ............................................................................................ 35

Health-Care Expenses ...................................................................................................... 38

Hardships from Natural Disasters ..................................................................................... 39

Banking and Credit

........................................................................................................ 43

Unbanked and Underbanked ............................................................................................. 43

Overdraft ......................................................................................................................... 46

Credit Outcomes and Perceptions ..................................................................................... 47

Credit Cards .................................................................................................................... 48

Buy Now, Pay Later ........................................................................................................... 49

iii

Housing

............................................................................................................................ 53

Living Arrangements ......................................................................................................... 53

Moving ............................................................................................................................ 54

Homeownership and Mortgages ........................................................................................ 55

Renting and Evictions ....................................................................................................... 56

Education

........................................................................................................................ 61

Modes of Learning in Primary and Secondary School .......................................................... 61

Perceptions of Children’s Performance in School ................................................................ 64

Modes of Learning in Higher Education .............................................................................. 65

Overall Value of Higher Education ...................................................................................... 66

Look Back on Education Decisions .................................................................................... 68

Student Loans

................................................................................................................ 71

Incidence and Types of Education Debt .............................................................................. 71

Student Loan Payment Status ........................................................................................... 73

Relation to Financial Well-Being ......................................................................................... 75

Relation to Self-Assessed Value of Higher Education .......................................................... 75

Retirement and Investments

....................................................................................... 77

Current Retirees .............................................................................................................. 77

Retirement Savings among Non-Retirees ........................................................................... 79

Financial Literacy and Experience with Investments ............................................................ 82

Description of the Survey

............................................................................................. 85

Survey Participation ......................................................................................................... 85

Targeted Outreach and Incentives ...................................................................................... 85

Survey Questionnaire ....................................................................................................... 86

Survey Mode ................................................................................................................... 86

Sampling and Weighting ................................................................................................... 87

Item Non-response and Imputation .................................................................................... 88

Acknowledgments

......................................................................................................... 91

Corrections

..................................................................................................................... 93

iv Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

Executive Summary

This report describes the responses to the 2021 Survey of Household Economics and Decision-

making (SHED). The Federal Reserve Board has fielded this survey each fall since 2013 to under-

stand the wide range of financial challenges and opportunities facing families in the United

States.

1

The findings in this report primarily reflect financial circumstances in late October and

early November of 2021, before the increase in coronavirus (COVID-19) cases from the Omicron

variant.

Despite persistent concerns that people expressed about the national economy, the survey high-

lights the positive effects of the recovery on the individual financial circumstances of U.S. fami-

lies. In 2021, perceptions about the national economy declined slightly. Yet self-reported financial

well-being increased to the highest rate since the survey began in 2013. The share of prime-age

adults not working because they could not find work had returned to pre-pandemic levels. More

adults were able to pay all their monthly bills in full than in either 2019 or 2020. Additionally, the

share of adults who would cover a $400 emergency expense completely using cash or its equiva-

lent increased, reaching a new high since the survey began in 2013.

Parents with children at home, who had been disproportionally affected by the pandemic in 2020,

exhibited notable improvements in their financial well-being in 2021. After declining in 2020, par-

ents’ assessments of their financial circumstances rebounded in 2021. This improvement is con-

sistent both with reduced childcare burdens as schools returned to in-person classes, as well as

additional financial resources provided to parents such as the enhanced child tax credit (CTC).

Most parents also said that their child was doing better academically, socially, and emotionally in

2021 than they were a year earlier.

The report also highlights several new topics added to the survey in 2021, such as disruptions

from natural disasters, rental debt, and employer vaccine mandates. These new questions provide

additional context on the experiences of U.S. adults in handling unexpected expenses, paying for

housing, and navigating ongoing changes in the labor market.

To better understand consumer experiences with emerging products, cryptocurrencies and “Buy

Now, Pay Later” (BNPL) products were included on the survey for the first time. While most adults

did not use cryptocurrencies in the prior year, cryptocurrency use as an investment was far more

1

The latest survey interviewed over 11,000 individuals in October and November 2021. The anonymized data, as well as

appendixes containing the complete SHED questionnaire and responses to all questions in the order asked, are also

available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/shed.htm.

1

common than use for transactions or purchases. However, while transactional use of cryptocurren-

cies was low, those using cryptocurrencies for purchases rather than as investments frequently

lacked traditional bank and credit card accounts.

The report also provides insights into long-standing issues related to individuals’ personal finan-

cial circumstances, including returns to education, housing situations, and retirement savings. In

many cases, the report finds that disparities by education, race and ethnicity, and income per-

sisted in 2021.

Key findings from the survey include the following:

Overall Financial Well-Being

In the fourth quarter of 2021, the share of adults who were doing at least okay financially increased

relative to 2020. With these improvements, overall financial well-being reached its highest level since

the survey began in 2013.

•

Seventy-eight percent of adults were either doing okay or living comfortably financially, the

highest share with this level of financial well-being since the survey began in 2013.

•

Parents experienced particularly large gains in financial well-being over the prior year. In 2021,

three-fourths of parents said they were doing at least okay financially, up 8 percentage points

from 2020.

•

Forty-eight percent of adults rated their local economy as “good” or “excellent” in 2021. This

share was up from 43 percent in 2020 but well below the 63 percent of adults who rated their

local economy as “good” or “excellent” in 2019, before the pandemic.

Income

The majority of parents received additional income in 2021 through the monthly CTC. Most higher-

income parents primarily saved this money, while most lower-income parents primarily spent it on

housing, items for their children, or food.

•

Three in 10 CTC recipients with income less than $50,000 used the largest portion of their

credit on housing expenses, just over 2 in 10 spent the largest portion on their child, and

15 percent spent the largest portion on food.

•

Fifteen percent of adults with income less than $50,000 struggled to pay their bills because

of varying monthly income. This challenge was even more acute among people who were par-

ents in this income range, of whom 27 percent struggled to pay their bills because of income

variability.

2 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

Employment

Many people switched jobs in 2021, and those who did generally said that their new job was better

than their old one. Most employees also said that their employer was taking about the right amount

of COVID-19 precautions, although some people not working indicated that concerns about the virus

contributed to the choice not to work.

•

Fifteen percent of workers said they were in a different job than 12 months earlier. Just over 6

in 10 people who changed jobs said their new job was better overall, compared with 1 in 10

who said that it was worse.

•

Seventy-seven percent of employees said their employers were taking the right amount of pre-

cautions against COVID-19. Those who did not were almost evenly split between thinking their

employers were taking too many and too few precautions.

•

Seven percent of all prime-age adults said that they were not working and that concerns about

getting COVID-19 contributed at least in part to their decision not to work.

•

Among those working from home, the share of employees who would look for another job if their

employer required they work in person was similar to the share who would look after a

pay freeze.

Dealing with Unexpected Expenses

The overall share of adults who would cover a small emergency expense using cash or its equivalent

increased to the highest level since 2013, when the survey began. Financial preparedness is an

important buffer for those who encounter unexpected events, such as medical expenses or disrup-

tions from natural disasters.

•

Sixty-eight percent of adults said they would cover a $400 emergency expense exclusively using

cash or its equivalent, up from 50 percent who would pay this way when the survey began in

2013.

•

Twenty percent of adults had major, unexpected medical expenses in the prior 12 months, with

the median amount between $1,000 and $1,999.

•

Sixteen percent of adults experienced a financial disruption or hardship from a natural disaster

or severe weather event in the prior year.

Banking and Credit

Most adults had a bank account and were able to obtain credit from mainstream sources in 2021,

but notable gaps in access to basic financial services still exist among Black and Hispanic adults

and those with low income.

Executive Summary 3

•

Six percent of adults did not have a bank account. Black (13 percent) and Hispanic (11 percent)

adults were more likely not to have a bank account than adults overall.

•

Eleven percent of adults with a bank account paid an overdraft fee in the previous 12 months,

with higher shares of low-income adults having overdrafted over this period.

•

Three percent of adults used cryptocurrency for purchases or money transfers. Among these

transactional users of cryptocurrencies, 13 percent did not have a bank account.

Housing

Low mortgage rates resulted in a continuation of the wave of refinancing in 2021, although high-

income borrowers were primarily the beneficiaries of this opportunity to reduce monthly housing

costs. The share of renters who had been behind on their rent in the prior 12 months was higher

than before the pandemic, and many still owed back rent at the time of the survey.

•

Nearly one-fourth of all homeowners with a mortgage refinanced their mortgage in 2021. This

includes nearly 3 in 10 mortgage holders with an income of at least $100,000, but a lower

16 percent of those with income under $50,000.

•

Seventeen percent of renters were behind on their rent at some point in 2021, including 8 per-

cent who were behind at the time of the survey in late 2021. Among those still behind in late

2021, the total outstanding back rent was between $9.3 billion and $10.9 billion.

Education

At the time of the survey, most parents of primary or secondary school students reported that their

children were attending classes completely in person. Most parents also said that their child was

doing better academically compared with a year earlier. In contrast to the experience of K–12 stu-

dents, online education remained prevalent at higher education institutions in the fall of 2021.

•

Ninety-three percent of parents with a child in public or private school said their youngest child

who was enrolled in K–12 education was attending classes completely in person, compared

with 27 percent attending completely in person in 2020.

•

Fifty-six percent of parents with a child in public or private school said that their child’s aca-

demic performance improved in 2021, compared with 7 percent who said it declined.

•

Seventy-six percent of higher education students in 2021 said they prefer online or

hybrid education, given the situation with the pandemic.

4 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

Student Loans

The share of student loan borrowers who were behind on their payments in the fall of 2021 declined

relative to before the pandemic. These borrowers also saw increases in their financial well-being

compared with prior years.

•

Twelve percent of borrowers were behind on their payments in 2021, a significant decline from

the 17 percent who were behind in the fall of 2019.

•

Seventy-three percent of those who went to college and have student loans for their own educa-

tion were doing at least okay financially in 2021, up from 65 percent before the pandemic.

Retirement and Investments

Among non-retirees, a higher share reported they felt like their retirement savings were on track than

in either 2020 or 2019. However, a sizeable share of recent retirees said COVID-related factors

affected the timing of their retirement decision.

•

Forty percent of non-retirees thought their retirement saving was on track, up from 36 percent in

2020 and 37 percent in 2019.

•

Twenty-five percent of adults who retired in the prior 12 months, and 15 percent of those who

retired one to two years ago, said factors related to COVID-19 contributed to when they retired.

Executive Summary 5

Overall Financial Well-Being

The share of adults doing at least okay financially rose to the highest level since the survey began

in 2013.

2

Although financial challenges and risks to the recovery remain, this generally positive

assessment of financial well-being was consistent with improved economic conditions and addi-

tional COVID-19 relief measures in 2021.

The increase in financial well-being occurred broadly across the population and was especially

large among parents. Even so, existing gaps by education and by race and ethnicity persisted.

Current Financial Situation

At the end of 2021, 78 percent of adults were

doing at least okay financially, meaning they

reported either “doing okay” financially

(39 percent) or “living comfortably” (39 per-

cent). The rest reported either “just getting

by” (16 percent) or “finding it difficult to get

by” (6 percent). The 78 percent of adults

doing at least okay financially in 2021 was up

3 percentage points from 2020 and was well

above the 62 percent doing at least this well

in 2013 (figure 1).

As further evidence of greater financial well-

being in 2021, the share of adults who said

they were living comfortably rose by 4 per-

centage points. This increase in financial well-

being aligns with improved economic condi-

tions and the additional COVID-19 relief

measures enacted in 2021.

3

2

The survey was fielded in October and November 2021 and results reflect financial situations at that time. References

to “in 2021” refer to the 12-month period before the survey rather than the precise calendar year.

3

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 became law in March 2021 and provided additional relief to most households to

address the continued impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; see https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-

bill/1319 and https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/American-Rescue-Plan-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

Figure 1. At least doing okay financially (by

year)

78

7575

75

74

70

69

65

62

202120202019201820172016201520142013

Percent

Note: Among all adults.

7

Adults with at least a bachelor’s degree continued to be much more likely to be doing at least okay

financially (91 percent) than those with less than a high school degree (49 percent). The 42 per-

centage point gap in well-being was little changed from the 44 percentage point gap in 2020

(figure 2). Moreover, looking over the past five years shows a steady and sizeable increase in

financial well-being among those with at least a bachelor’s degree (an increase of 9 percentage

points in the share doing at least okay from 2016 to 2021), while adults with less than a high

school degree have not experienced lasting gains in financial well-being.

Parents were one group that experienced particularly large gains in financial well-being over the

prior year. In 2021, three-fourths of parents said they were doing at least okay financially, up 8 per-

centage points from 2020 (figure 3).

Low-income parents saw even more substantial increases in their financial well-being in 2021.

Among parents with income under $25,000, the share doing at least okay financially rose by

13 percentage points, from 40 percent in 2020 to 53 percent in 2021. The share of parents with

income between $25,000 and $49,999 who were doing at least okay financially increased by

7 percentage points, while those with higher income exhibited more modest improvements.

A potential explanation for the large rise in financial well-being among parents is the expansion of

the CTC. The American Rescue Plan temporarily increased the CTC from $2,000 per child to

$3,000 per child ($3,600 for a child under age 6), increased eligibility among low-income families,

Figure 2. At least doing okay financially (by year and education)

Percent

Bachelor’s degree

or more

Some college/technical

or associate degree

High school

degree or GED

Less than a high

school degree

202120202019201820172016201520142013

89

88

87

85

82

80

7777

62

55

47

42

48

46

56

49

54

45

60

64

64

69 69

66

67

62

66

68

69

72

73

72

91

49

70

74

Note: Among all adults. Results for 2017 to 2019 differ slightly from previous reports because of adjustments in educa-

tion coding for consistency.

8 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

and paid the credit monthly (the “Income” section of this report discusses how parents used this

credit).

4

Many families also saw a return to in-person schooling in the fall of 2021, which may

have eased childcare responsibilities and allowed some parents to return to work or work

more hours.

The increase in financial well-being among parents in 2021 contrasts with the decline they experi-

enced from 2019 to 2020 (figure 3).

5

Parents were hit especially hard by the pandemic in 2020,

having experienced higher rates of job loss and having faced disruptions to childcare and in-person

K–12 schooling that affected their availability to work. (See the report Economic Well-Being of U.S

Households in 2020 for additional information).

6

4

More details on the enhanced CTC are available from U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Child Tax Credit,” https://

home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-american-families-and-workers/child-tax-credit.

5

Results in earlier years were updated for consistency with 2021 methods for classifying education status so may differ

slightly from earlier reports.

6

See Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2020, https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2020-report-

economic-well-being-us-households-202105.pdf.

Figure 3. At least doing okay financially (by year and parental status)

Percent

Parents (living with own children under age 18)

All other adults

2021202020192018201720162015

79

78

77

76

75

71

70

65

68

71

72

71

67

75

Note: Among all adults.

Overall Financial Well-Being 9

Differences in financial well-being across racial and ethnic groups persisted in 2021. Eighty-

eight percent of Asian adults were doing at least okay financially, followed by 81 percent of White

adults, 71 percent of Hispanic adults, and 68 percent of Black adults (figure 4).

7

All racial and ethnic groups measured in the survey saw an increase in financial well-being over the

prior year, with Hispanic adults seeing a particularly sharp increase. In 2021, the 71 percent of

Hispanic adults who said they were doing at least okay was up 7 percentage points from 2020.

The increase in well-being for Hispanic adults was largely concentrated among parents, similar to

the pattern for adults overall. The share of Hispanic parents doing at least okay increased 14 per-

centage points (to 70 percent) in 2021. However, Hispanic adults not living with their own children

under age 18 saw a relatively slight increase (figure 5).

7

The reported categorizations reflect the largest statistical groupings but are neither exhaustive nor the only distinctions

important to understand. Sample sizes for other racial and ethnic groups and subpopulations are not large enough to

produce reliable estimates. Asian adults were separately identified for the first time in the survey in the Economic Well-

Being of U.S. Households in 2020, and in 2021 the Federal Reserve Board identified Asian adults in earlier years of the

survey. However, results for Asian adults are sometimes excluded when the sample size is insufficient to provide a reli-

able estimate.

Figure 4. At least doing okay financially (by year and race/ethnicity)

Percent

84

80

79

85

78

81

77

78

72

79

71

75

68

79

65

75

56

53

61

65

66

66

65

55

55

63

64

64

67

66

64

64

88

81

71

68

Asian

Hispanic

Black

White

202120202019201820172016201520142013

Note: Among all adults.

10 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

Other dimensions across which financial well-being differed include income, geography, LGBTQ+

status, and disability status (table 1). Fifty-five percent of adults with family income less than

$25,000 were doing at least okay financially, compared with 96 percent of adults with family

income greater than $100,000. People living in low- or moderate-income communities also had

lower levels of financial well-being than those living in middle- or upper-income communities.

8

Addi-

tionally, those living in metro areas were faring better than those in non-metro communities.

9

Other surveys have shown that adults identifying as LGBTQ+ were more likely to face economic

insecurity, suggesting LGBTQ+ status may be associated with financial well-being.

10

Consistent

with this evidence, the 2021 SHED found that 67 percent of adults identifying as LGBTQ+ were

doing at least okay financially, compared with 78 percent of the overall population.

11

Moreover, an

even lower 62 percent of adults who were transgender or nonbinary, or who reported their sexual

8

Neighborhood income is defined using the Community Reinvestment Act definition. Under this definition, low- and

moderate-income refers to communities that have a median family income of less than 50 percent of the area median

income. For details on the definition, see https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/cra_resources.htm.

9

Non-metro areas are defined throughout this report as being outside of a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), and metro

areas are those inside of an MSA, as defined by the Office of Management and Budget. This definition differs from the

Census Bureau’s definition of urbanized areas. For details, see U.S. Census Bureau, “2010 Urban Area FAQs,” https://

www.census.gov/programs-surveys/geography/about/faq/2010-urban-area-faq.html.

10

For example, see U.S. Census Bureau, “Household Pulse Survey Shows LGBT Adults More Likely to Report Living in

Households with Food and Economic Insecurity than Non-LGBT Respondents,” https://www.census.gov/library/stories/

2021/08/lgbt-community-harder-hit-by-economic-impact-of-pandemic.html.

11

Survey respondents could report their sexual orientation and gender identity on a demographic profile survey previously

conducted by the survey vendor. Respondents are classified as LGBTQ+ based on responses to these questions.

Figure 5. At least doing okay financially (by year, race/ethnicity, and parental status)

2021202020192018

Asian Hispanic BlackWhite

2021202020192018

Percent Percent

84

84

82

66

67

68

67

69

68

79

80

82

88

70

71

82

83

87

79

63

62

53

66

62

56

76 76

73

89

61

70

79

Parents All other adults

Note: Among all adults. Parents are adults living with their own children under age 18.

Overall Financial Well-Being 11

orientation as something other than straight,

gay, lesbian, or bisexual, were doing at least

okay financially.

12

Finally, 60 percent of adults with a disability

were doing at least okay financially, markedly

lower than the overall population.

13

Prior to

2021, the SHED did not include disability

status, so we cannot observe how financial

well-being has evolved for adults with a dis-

ability through the pandemic. However, as dis-

cussed in the “Employment” section of this

report, other surveys find evidence of an

increase in employment among adults with a

disability in recent years.

Changes in Financial Situation

over Time

The survey also tracks overall financial well-

being by asking respondents whether they are

better or worse off financially than they were

12 months earlier. Measuring well-being in

this way helps track changes in perceived well-

being over time, as some individuals may feel

worse off financially than they were a year ear-

lier, for instance, even if they feel they are still

doing okay overall (or that their financial well-

being is improving even if they are still strug-

gling overall).

The share of adults who said they were worse off financially than a year earlier fell from 24 per-

cent in 2020 to 20 percent in 2021, yet remained much higher than the 14 percent seen in 2019,

12

Differences in financial well-being between adults identifying as LGBTQ+ and other adults were present across age

groups. For example, only 58 percent of LGBTQ+ adults ages 45 to 54 were doing at least okay, compared with 75 per-

cent among all adults in that age group.

13

Disability status is defined based on a five-question functional limitation sequence that asks about hearing, vision,

ambulatory, self-care, and independent living difficulties. This approach for determining disability status is similar to the

six-question sequence used for the American Community Survey (see U.S. Census Bureau, “How Disability Data Are Col-

lected from the American Community Survey,” https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-

collection-acs.html).

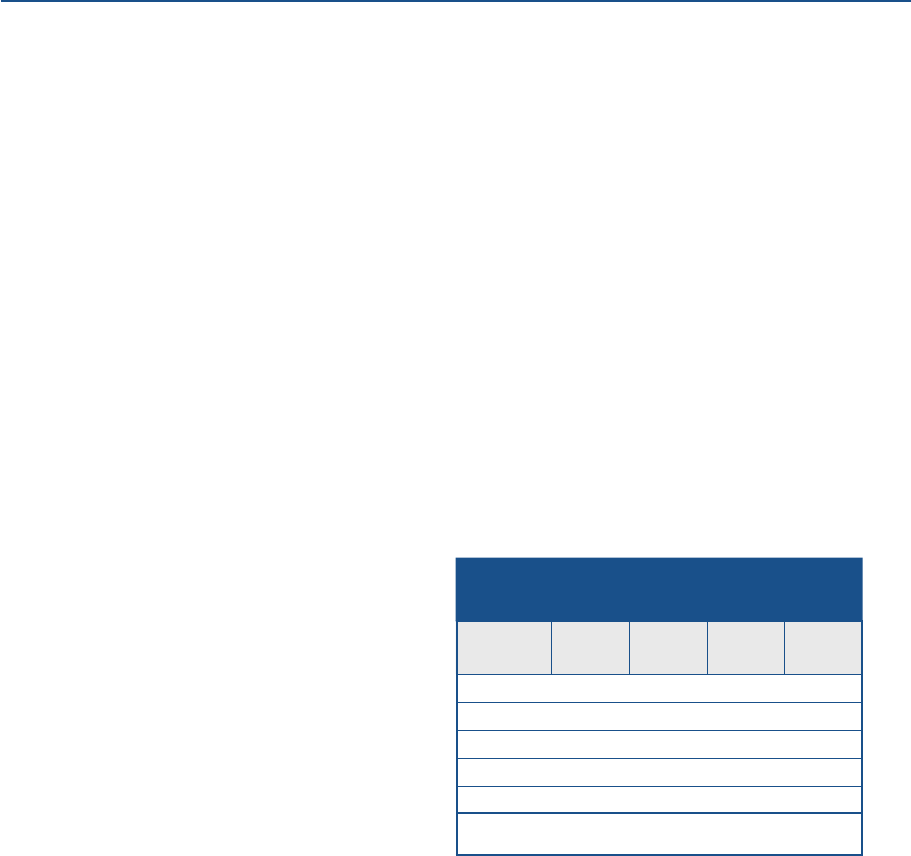

Table 1. At least doing okay financially (by

demographic characteristics)

Percent

Characteristic 2021

1-year

change

5-year

change

Family income

Less than $25,000 55 3 8

$25,000–$49,999 67 2 5

$50,000–$99,999 85 1 5

$100,000 or more 96 1 4

Disability status

Disability 60 n/a n/a

No disability 81 n/a n/a

LGBTQ+ status

Identifies as LGBTQ+ 67 -1 n/a

Does not identify as LGBTQ+ 79 2 n/a

Marital status

Married 86 4 9

Not married 67 0 6

Place of residence

Metro area 79 3 9

Non-metro area 72 3 4

Neighborhood income

Low or moderate income 66 4 6

Middle or upper income 82 2 9

Overall 78 3 8

Note: Among all adults. Low- or moderate-income neighbor-

hoods are defined here using the definition from the Community

Reinvestment Act. LGBTQ+ status was first identifiable in the

2019 survey and disability status was first identifiable in the

2021 survey. Here and in subsequent tables and figures, per-

centages may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

n/a Not applicable.

12 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

before the pandemic (figure 6). The share doing about the same as a year earlier increased 3 per-

centage points to 54 percent, while the share who said they were better off was unchanged at

25 percent.

When asked to compare their financial situation to two years ago, before the pandemic, nearly

one-fourth (24 percent) said they were worse off. Forty percent said they were doing about the

same, and 36 percent said they were better off than two years ago.

14

Those who were doing

worse off than before the pandemic were disproportionately adults with lower family income and

less education.

To get a longer-term perspective, individuals were also asked to compare their current financial cir-

cumstances to how they perceived their parents’ financial situation at the same age. Looking

across a generation shows evidence of economic progress over time, despite financial setbacks

during the pandemic. A majority of adults (57 percent) thought they were better off financially than

their parents were, up from 54 percent in 2020 and back to the pre-pandemic level from 2019.

Twenty-one percent thought they were worse off than their parents were at the same age.

14

A subset of respondents completed both the 2020 and 2021 surveys. Combining the one-year change in well-being

results in the 2020 and 2021 surveys for these repeat respondents leads to similar results. Twenty-four percent

reported that their financial well-being declined in one year and did not improve in the other, while 34 percent indicated

that their well-being improved in one year and did not decline in the other. The remaining 43 percent either said their

well-being was about the same in each year (35 percent) or had an improvement in one year and a decline in the other

(7 percent).

Figure 6. Financial situation compared with 12 months prior (by year)

Percent

Better off

Worse off

20212020201920182017201620152014

25

32

31

33

2727

29

21

19

17

15

13

14

25

20

24

Note: Among all adults.

Overall Financial Well-Being 13

People holding at least a bachelor’s degree were more likely to experience upward economic

mobility, relative to those with less education. This is particularly true among first-generation col-

lege graduates, among whom 70 percent thought they were better off financially than their par-

ents were.

15

Local and National Economic Conditions

Along with questions about their own financial circumstances, people were asked to rate their

local economy and the national economy as “excellent,” “good,” “only fair,” or “poor.” The share of

adults rating their local economy favorably increased from 2020 to 2021. Forty-eight percent of

adults rated their local economy as “good” or “excellent” in 2021, with the rest rating conditions

as “only fair” or “poor.” This share was up from 43 percent in 2020, but well below the 63 percent

of adults who rated their local economy as “good” or “excellent” in 2019, before the pandemic.

This pattern was generally similar across

racial and ethnic groups, with higher shares

rating their local economy favorably relative to

2020 but still below the share from 2019

(table 2). One exception was Black adults: the

share of Black adults rating their local

economy favorably increased 10 percentage

points from 2020 to 2021, and was much

closer to the pre-pandemic level than for other

groups. However, Black and Hispanic adults

remained the least likely to report that their

local economy was faring well.

People’s perceptions about their local

economy diverged in 2021 for metro and non-

metro areas. While perceptions of the local economy improved for residents of metro areas, per-

ceptions ticked down 1 percentage point for those in non-metro areas. Additionally, the 34 percent

of non-metro residents who rated their local economy as “good” or “excellent” remained far below

the 53 percent that did so in 2019.

15

First-generation college graduates are those who have at least a bachelor’s degree and who report that neither of their

parents completed at least a bachelor’s degree.

Table 2. Self-assessment of the local economy

as good or excellent (by race/ethnicity and

place of residence)

Percent

Characteristic 2019 2020 2021

Race/ethnicity

White 67 46 50

Black 46 32 42

Hispanic 57 39 44

Asian 72 44 61

Place of residence

Metro area 65 44 50

Non-metro area 53 35 34

Note: Among all adults.

14 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

Similar to people’s perceptions of their local

economy, the share rating the national

economy favorably fell precipitously from 2019

to 2020, after the onset of the pandemic

(figure 7). However, people’s perceptions of

the national economy continued to decline in

2021. Only 24 percent of adults rated the

national economy as “good” or “excellent” in

2021, down 2 percentage points from 2020

and about half the rate seen in 2019. This

trend contrasts starkly with people’s increas-

ingly favorable assessment of their own finan-

cial well-being.

Overall Life Satisfaction

In addition to questions on financial well-

being, the 2021 survey included a question on

overall life satisfaction to provide a broader

look at how people were faring. Respondents rated how satisfied they were with life as a whole on

a scale from 0 to 10. Fifty-eight percent of adults reported “high” life satisfaction (rating 7 to 10),

30 percent reported “medium” life satisfaction (rating 4, 5, or 6), and 11 percent reported “low”

life satisfaction (rating 0 to 3).

Life satisfaction was strongly associated with income. Nearly three-fourths (73 percent) of adults

with family income of $100,000 or more reported high life satisfaction, compared with 41 percent

among those with family income less than $25,000. Differences by education were also large, as

were those by disability status and LGBTQ+ status (table 3).

16

Differences in overall life satisfaction by race/ethnicity, on the other hand, were small. The shares

of White, Black, and Hispanic adults reporting high life satisfaction were all within 2 percentage

points of the share doing so for the overall population. Asian adults exhibited the largest differ-

ence from the overall population, with 63 percent reporting high life satisfaction.

16

The scales used to measure life satisfaction and financial well-being are not directly comparable.

Figure 7. Assessment of own financial

well-being, local economy, and national

economy (by year)

78

757575

74

41

51

50

26

24

57

64

63

43

48

Own financial

well-being

(doing at least okay)

Local

economy

(good or excellent)

National

economy

(good or excellent)

20212020201920182017

Percent

Note: Among all adults.

Overall Financial Well-Being 15

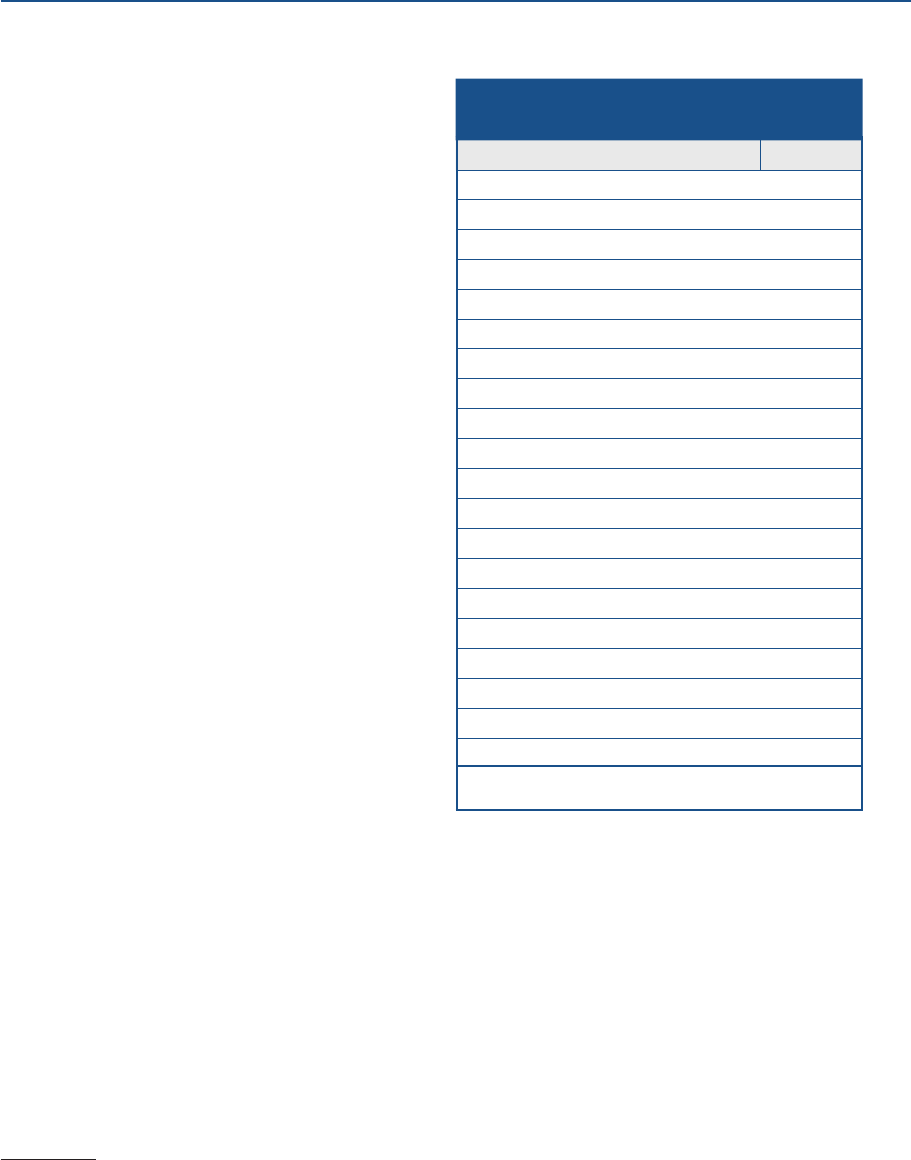

Table 3. Share of adults with high life satisfaction (by demographic characteristics)

Characteristic Percent

Family income

Less than $25,000 41

$25,000–$49,999 51

$50,000–$99,999 61

$100,000 or more 73

Education

Less than a high school degree 40

High school degree or GED 53

Some college/technical or associate degree 55

Bachelor’s degree or more 67

Race/ethnicity

White 59

Black 56

Hispanic 57

Asian 63

Disability status

Disability 41

No disability 62

LGBTQ+

Identifies as LGBTQ+ 46

Does not identify as LGBTQ+ 60

Parental status

Not living with own children under age 18 57

Parent (living with own children under age 18) 62

Place of residence

Metro area 59

Non-metro area 53

Overall 58

Note: Among all adults.

16 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

Income

Income is central to most people’s financial well-being. Recognizing this, the survey included a

series of questions on income level and sources, as well as monthly income volatility.

Most parents with a child under age 18 received additional income in 2021 from the CTC. Parents

used these monthly payments in a variety of ways, including saving them, spending them on food,

and spending them on rent, mortgage, and utilities.

Most adults had income that was roughly the same each month. For adults with varying monthly

income, 3 in 10 reported that the volatility caused financial challenges. Income variability was

more likely to result in financial challenges among those with lower income.

Level and Source

Family income in this survey is the cash

income from all sources, before taxes and

deductions, that the respondents and their

spouse or partner received during the pre-

vious year. Income is reported in dollar ranges

and not exact amounts. Just over one-fourth

of adults had a family income below $25,000

in 2021, and nearly one-third had $100,000

or more (table 4).

Family income varied dramatically by race and ethnicity in 2021. Forty-three percent of Black

adults and 40 percent of Hispanic adults had a family income below $25,000. This is at least

twice the rate among White and Asian adults. Conversely, White and Asian adults were dispropor-

tionately likely to have family income above $100,000.

Labor earnings were the most common source of income, but many people had other sources of

income as well. Sixty-seven percent of adults and their spouse or partner received wages,

Table 4. Family income (by race/ethnicity)

Percent

Race/

ethnicity

Less than

$25,000

$25,000–

$49,999

$50,000–

$99,999

$100,000

or more

White 20 16 27 37

Black 43 18 22 17

Hispanic 40 18 22 20

Asian 17 10 23 51

Overall 26 16 25 32

Note: Among all adults.

17

salaries, or self-employment income (collectively referred to here as labor income) (figure 8),

matching the share from 2020. Yet, 59 percent of adults and their spouse or partner received non-

labor income in 2021.

17

The share of adults receiving unemployment income in 2021 (9 percent) remained higher than

before the pandemic but was lower than in 2020, when the job losses caused by the COVID-19

pandemic peaked. Individuals who received income from unemployment insurance in 2021

reported that they were most likely to learn about their eligibility from their employer (45 percent),

followed by their own internet research (32 percent).

Assistance from nonprofits and private sources—including financial support from a friend or family

member living outside of their home—can also supplement family income. Fifteen percent of

adults ages 21 and older received at least one type of assistance from private or nonprofit

17

Non-labor income is defined as income from interest, dividends, or rental income; social security (including old age and

Disability Insurance (DI)); Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), or cash

assistance from a welfare program; unemployment income; or income from a pension. Non-labor income does not

include Economic Impact Payments, tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, or in-kind benefits.

Figure 8. Family income sources

2021

2020

Any non-labor income

Unemployment income

SSI, TANF, or cash assistance

from a welfare program

Social security

(including old age and DI)

Interest, dividends,

or rental income

Non-labor income

Wages, salaries, or

self-employment income

Percent

67

67

32

33

27

27

5

5

14

9

61

59

Note: Among all adults. Respondents could select multiple answers. DI is Disability Insurance; SSI is Supplemental

Security Income; and TANF is Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. Key identifies bars in order from top to bottom.

18 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

sources in 2021 (table 5). Nearly 1 in 10 adults received groceries or meals from a food pantry,

religious organization, or community organization, down 2 percentage points from 2020.

Seven percent of adults ages 21 and older received financial assistance from a friend or family

member living outside of their home, essentially unchanged from 2020. On the other hand, 15 per-

cent of adults provided support to others.

Adults with less education were more likely to receive at least one type of assistance from private

or nonprofit sources. More than 3 in 10 (34 percent) adults with less than a high school degree

received this type of assistance, compared with less than 1 in 10 adults with at least a bach-

elor’s degree.

Child Tax Credit

Starting in July 2021, most parents of children under age 18 saw their income supplemented by

the enhanced CTC. Eighteen percent of all adults, and 70 percent of adults living with their chil-

dren under age 18, reported receiving monthly CTC payments in 2021.

18

An additional 5 percent

of adults living with children under age 18 did not know if they received monthly CTC payments.

Parents who received monthly CTC payments most frequently saved the payments, spent them on

their child, or used them for necessities. Saving was the most common use of the monthly CTC

payments, with 43 percent of recipients saying they saved at least a portion of them.

18

This estimate corresponds to 27 million payments to 52 million children. Administrative data from the Treasury Depart-

ment find that 36 million payments were made in December 2021 for 61 million qualifying children (U.S. Department of

the Treasury, By State: Advance Child Tax Credit Payments Distributed in December 2021 (Washington, DC: Department of

the Treasury, December 2021), https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Advance-CTC-Payments-Disbursed-

December-2021-by-State-12152021.pdf). The lower estimate of parents reporting the credit in the SHED suggests that

some parents either did not know their family received the payment or did not know that it was the CTC.

Table 5. Financial assistance received (by educational attainment)

Percent

Characteristic

Free groceries

or meals

Financial support

from religious

or community

organization

Financial support

from friends or

family not

in household

Received at least

one type of private

or nonprofit

support

Less than a high school degree 27 5 15 34

High school degree or GED 13 2 7 17

Some college/technical or associate degree 10 2 9 17

Bachelor’s degree or more 3 1 5 8

Overall 9 2 7 15

Note: Among adults age 21 and older. Respondents could select multiple answers.

Income 19

Other common uses were spending on their

child (40 percent); spending on food (31 per-

cent); and spending on rent, mortgage, or utili-

ties (29 percent) (table 6).

Respondents were also asked how they used

the largest portion of the monthly CTC pay-

ments. Saving the monthly payment was again

the most common response (36 percent), with

many others saying that they spent the largest

portion on their child or on rent, mortgage, or

utilities.

The ways people used the CTC payments varied by income. Higher-income adults were most likely

to save the largest portion of their credit, whereas lower-income adults were most likely to spend it

on housing. For instance, 54 percent of recipients with income of at least $100,000 saved the

largest portion of their credit, whereas only 18 percent of recipients with income less than

$25,000 did so (table 7).

Income Variability

Since many bills must be paid monthly, variations in monthly income can lead to financial chal-

lenges. Most adults had income that was roughly the same each month, but about 3 in 10 had

income that varied from month to month. This share was essentially unchanged from 2020.

Since income variability can result from either dips or spikes in monthly income, the survey asked

those who reported varying monthly income whether they struggled to pay bills as a result.

Thirty percent of those who experienced varying monthly income, representing slightly less than

Table 6. Uses for Child Tax Credit (CTC)

Percent

Purpose

Used any

for purpose

Used largest

portion

for purpose

Saved it 43 36

Paid off debt 21 10

Spent on child 40 20

Spent on rent, mortgage, or utilities 29 17

Spent on food 31 12

Spent on other things 12 5

Note: Among parents with a child under age 18 who reported

receiving CTC payments. Respondents could select multiple

answers.

Table 7. Use for largest portion of Child Tax Credit (by family income)

Percent

Purpose

Less than

$25,000

$25,000–

$49,999

$50,000–

$99,999

$100,000

or more

Saved it 18 15 33 54

Paid off debt 14 9 9 10

Spent on child 22 22 22 16

Spent on rent, mortgage, or utilities 29 33 18 6

Spent on food 13 19 15 7

Spent on other things 5 2 5 7

Note: Among parents with a child under age 18 who reported receiving CTC payments.

20 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

1 in 10 adults overall, said they struggled

to pay their bills at least once in the

past 12 months because of varying

monthly income.

Lower-income adults were more likely to have

varying monthly income and to report that they

struggled to pay their bills at least once in the

past 12 months as a result (table 8). Fif-

teen percent of adults with income less than

$50,000 struggled to pay their bills because

of varying monthly income. Among lower-

income parents, an even greater 27 percent

struggled to pay their bills because of income

variability.

Adults with and without a disability were simi-

larly likely to experience income variability.

However, when those with a disability experi-

enced such variability, it was more likely to

lead to a hardship.

Income variability also continued to differ greatly by industry in 2021. Workers in the leisure and

hospitality industry were the most likely to have varying monthly income (figure 9).

Table 8. Income volatility and related hardship

(by family income, race/ethnicity, and disability

status)

Percent

Characteristic

Varying

income,

causes

hardship

Varying

income,

no hardship

Stable

income

Family income

Less than $25,000 16 23 61

$25,000–$49,999 14 17 69

$50,000–$99,999 6 18 75

$100,000 or more 1 19 79

Race/ethnicity

White 7 19 75

Black 12 19 69

Hispanic 14 23 63

Asian 4 20 76

Disability status

No disability 7 20 72

Disability 13 15 72

Overall 9 20 72

Note: Among all adults.

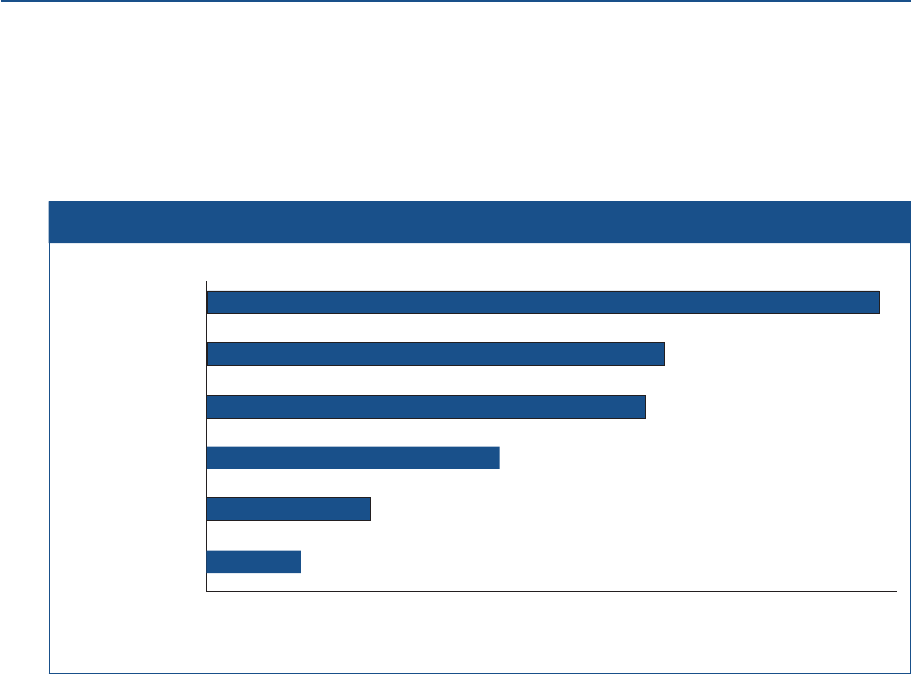

Figure 9. Income varied at least occasionally from month to month (by industry)

Public administration

Armed forces

Professional and business services

Financial activities

Manufacturing

Information

Education and health services

Transportation and utilities

Other services

Construction

Wholesale and retail trade

Natural resources and mining

Leisure and hospitality

Percent

47

42

39

37

35

34

27

27

27

24

22

22

21

Note: Among adults who reported industry of employment.

Income 21

These workers also reported the highest rates of hardship because of their varying income. How-

ever, the prevalence of income variability within the leisure and hospitality industry was similarly

high both before and after the pandemic.

22 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

Employment

The share of adults who were working in late 2021 remained below the pre-pandemic level. Health

limitations, concerns about COVID-19, and family responsibilities were common reasons for not

working. Many also switched jobs in 2021, and those who did generally said their new job was

better than their old one.

Reasons for Not Working

Twenty-three percent of prime-age adults (ages 25 to 54) were not working in October 2021, down

from 26 percent in 2020, but up from 21 percent in 2019, before the pandemic.

19

Health limitations and concerns about getting

COVID-19 were commonly cited reasons for not

working. Twelve percent of all prime-age adults

were not working, at least in part, for one of

these reasons. Health limitations or disability

were cited by 9 percent and specific concerns

about COVID-19 were cited by 7 percent

(figure 10). Family responsibilities were also

commonly cited as reasons for not working.

The proportion of prime-age adults who said

that they were not working because they could

not find work fell from 9 percent in 2020 back

to 5 percent in 2021, the same as before the

pandemic.

20

Two percent of all prime-age adults said that

they were not working, at least in part,

because they didn’t want to lose access to unemployment insurance or other government ben-

19

This pattern is consistent with that observed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, who reported 22 percent not working in

October 2021, down from 24 percent not working at the time of the survey in 2020, but up from 20 percent in October

2019. See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “(Seas) Employment-Population Ratio—25–54 yrs.,” https://data.bls.gov/

timeseries/LNS12300060.

20

Some of the decrease could have been due to a change in the questionnaire from 2020 to 2021 to include an addi-

tional reason that respondents could give for why they were not working, although respondents still could give mul-

tiple answers.

Figure 10. Reasons for not working among

prime-age adults

1

1

2

4

5

7

9

7

Percent

Retired

School or training

Access to government

benefits

Childcare

Could not find work

Family obligations

besides childcare

Concerned about

COVID-19

Health limitations or

disability

Note: Among adults ages 25 to 54. Respondents

could select multiple answers.

23

efits.

21

Among those whose family received government benefits in the prior year, 6 percent indi-

cated that benefit eligibility contributed to them not working.

22

However, even among benefit recipi-

ents, other factors including concerns about COVID-19 exposure (15 percent) and an inability to

find work (11 percent) were more likely to be cited as reasons for not working.

Prime-age women were particularly likely to say that they were not working because of childcare

and other family responsibilities. Six percent of prime-age women cited childcare as a reason for

not working, and 10 percent cited other family responsibilities, far exceeding that for men

(figure 11). However, the share of women not working because of childcare responsibilities did not

increase relative to that seen before the pandemic.

Another difference between prime-age men and women is that women were more likely to say they

were not working, at least in part, because of concerns about getting COVID-19. Eight percent of

21

The survey was conducted in the fourth quarter of 2021, after the expiration of expanded unemployment insurance pro-

grams in September.

22

Government benefit recipients include prime-age adults whose family received unemployment insurance, Social Security,

Supplemental Security Income, TANF, other cash welfare assistance, SNAP benefits, Medicare, or Medicaid.

Figure 11. Reasons for not working among prime-age adults (by gender)

Women

Men

Retired

School or training

Access to government

benefits

Childcare

Could not find work

Family obligations

besides childcare

Concerned about

COVID-19

Health limitations

or disability

Percent

8

8

10

5

5

5

5

1

1

1

6

2

2

2

2

9

Note: Among adults ages 25 to 54. Respondents could select multiple answers. Key identifies bars in order from top

to bottom.

24 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

prime-age women cited concern about getting the virus as a reason for not working, compared with

5 percent of prime-age men. Previous studies have found that occupations with more women

working in them before the pandemic had higher rates of COVID-19 exposure.

23

Working from Home

A major change in many people’s work lives since 2019 was the increased prevalence of working

from home, also known as remote work. During the week of the survey in late 2021, 22 percent of

adults who worked for someone else (“employees”) worked entirely from home. This share was

down from 29 percent in 2020, but well above the 7 percent who worked entirely from home in

2019, before the pandemic.

24

In addition, 17 percent of employees said they worked from home

some of the time during the week of the survey in 2021. For some workers, such as those with

disabilities, the increased prevalence of remote work in recent years may have facilitated greater

participation in the labor market (see box 1).

Employees with more education were much

more likely to work from home than those with

less education. Thirty-three percent of

employees with at least a bachelor’s degree

worked entirely from home, whereas 14 per-

cent of employees with some college, and

9 percent with a high school degree or less,

did so (figure 12).

25

One reason for the differences by education is

that employees with more education were

more likely to have a job where they could

work from home. Nearly three-fourths of

employees with a bachelor’s degree or more

either worked from home or said that they could if their employer would let them, compared with

29 percent of employees with a high school degree or less. Overall, 53 percent of employees

either worked from home or said that they could if their employer would let them.

23

Stefania Albanesi and Jiyeon Kim, “Effects of the COVID-19 Recession on the U.S. Labor Market: Occupation, Family,

and Gender,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 35, no. 3 (Summer 2021): 3–24, https://www.aeaweb.org/

articles?id=10.1257/jep.35.3.3.

24

The question asked in 2019 was different from 2020 and 2021. The 2019 survey asked where people worked in their

main jobs most of the time.

25

There is variation across industry in the likelihood of working from home, although even within an industry those with a

bachelor’s degree are generally more likely to work from home than are those with less education.

Figure 12. Amount of work done from home

(by education)

AllSomeNone

Bachelor’s degree

or more

Some college/

technical or

associate degree

High school

degree or less

81

9 9

14

33

11

24

75

43

Percent

Note: Among adults who worked for someone else.

Key identifies bars in order from left to right.

Employment 25

Box 1. Pandemic Employment Experiences of Adults with a

Disability

Individuals with a disability have long faced significant barriers in the labor market. Before the pan-

demic, in February 2020, the employment rate among individuals with a disability was only 19 percent,

compared with 67 percent among those without a disability. Most of this gap was due to individuals

with a disability being out of the labor force, meaning they were not looking for work.

1

The widespread

disruptions to the labor market during the pandemic created unique challenges for adults with disabili-

ties, but the restructuring of how work is conducted also created an opportunity for some to enter the

labor force and contribute in ways that were not previously possible.

Despite the additional pandemic-related hurdles, employers’ increased reliance on working from home

and remote work had the potential to expand employment opportunities for a wide array of workers with

a disability. Thirty-three percent of workers with a disability who had less than a bachelor’s degree

worked from home some of the time in the week before the survey, compared with 25 percent of their

peers without a disability (figure A). Among workers with at least a bachelor’s degree, a higher share

worked from home, and the shares were similar among workers with and without a disability. The

increase in remote work opportunities during the pandemic may have contributed to the more rapid

recovery in employment rates since the start of the pandemic among workers with disabilities observed

in other data.

2

Bachelor’s degree

or more

No disabilityDisability

Figure A. Worked from home at least some of the time (by education and disability status)

Note: Among adults who worked in the month prior to the survey. Key identifies bars in order from top to bottom.

Less than a

bachelor’s degree

Percent

33

25

60

58

(continued)

1

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “(Unadj) Employment-Population Ratio—With a Disability, 16 Years and Over” https://data.bls.gov/

timeseries/LNU02374597; and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “(Unadj) Employment-Population Ratio—With No Disability, 16 Years

and Over,” https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNU02374593.

2

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the employment to population ratio of workers with a disability in October 2021 was

1 percentage point above pre-pandemic levels from February 2020 while remaining 2 percentage points below pre-pandemic levels

among those without a disability.

26 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

Most employees who worked from home, or who said they could if their employer would let them,

would prefer to work from home. Eighty-nine percent said they would like to work from home at

least some of the time. Forty-one percent said

they would prefer to do so all of the time.

Employees who preferred to work from home

at least some of the time most commonly

cited less time commuting and work-life bal-

ance as reasons (figure 13). Both were cited

by 89 percent of employees who preferred to

work from home.

Another common reason employees said they

preferred to work from home was increased

productivity. Seventy percent of employees

who preferred to work from home said that

one reason for their preference was that they

were more productive at home. While lower,

Figure 13. Reasons employees prefer to work

from home

Percent

Able to live in a

different area

Work–life balance

Concerns about

COVID-19

More productive

working at home

Less time commuting

89

70

56

89

47

Note: Among employees who worked from home or

could work from home if their employer allowed, who

also said they preferred working from home at least

some of the time. Respondents could select multiple

answers.

Box 1—continued

Nevertheless, with the unprecedented health challenges that the pandemic presented to the general

population, adults with a disability faced significant difficulties that may be exacerbated by their dis-

ability. For some types of disabilities, contracting COVID-19 may present unique difficulties in going

about one’s day or receiving care. Further compounding matters, comorbidities are more prevalent

among adults with a disability, meaning a COVID-19 infection may be more likely to result in serious ill-

ness or death.

3

Consequently, workers with a disability may have different preferences on workplace COVID-19 precau-

tions. This, in turn, could affect their employment decisions. After controlling for their level of educa-

tion, employees with a disability were more likely to favor a vaccine mandate relative to those without a

disability.

Additionally, among those who were not working, people with a disability were more likely to say that

concerns about contracting COVID-19 contributed to their not working. Among adults with at least a

bachelor’s degree, 19 percent of those with a disability reported that COVID-19 concerns were a con-

tributing factor. This is nearly twice the frequency of these concerns among similarly educated people

without a disability. Among those with less than a bachelor’s degree, just over one-fifth of nonworkers

with a disability, and just under one-fifth of nonworkers without a disability, said that COVID-19 concerns

were a factor in their employment decision. Consequently, while employment rates among workers with

a disability have improved recently, health and safety concerns appear to be hampering their employ-

ment growth more than among other adults.

3

Sally-Ann Cooper, Gary McLean, Bruce Guthrie, Alex McConnachie, Stewart Mercer, Frank Sullivan, and Jull Morrison, “Multiple

Physical and Mental Health Comorbidity in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: Population-Based Cross-Sectional Analysis,” BMC

Family Practice, 16, no. 1 (2015): 1–11.

Employment 27

56 percent of employees who preferred to work from home said that concerns about COVID-19

contributed to their preference.

Many of those who worked from home at least some of the time also said that they would actively

look for another job if their employer required them to work in person each workday. Forty-five per-

cent said they were at least somewhat likely to look for another job or leave their job if their

employer required them to work in person each workday.

26

Twenty-two percent were very likely.

Among those working from home full time, an even larger 55 percent said that they would be

somewhat or very likely to look for another job if required to report in person each workday.

For context on the importance of the ability to work from home in people’s job decisions, the

survey also asked respondents about their likelihood of looking for another job if their employer

froze their pay or cut their pay by various amounts.

27

The share of employees who were at least

somewhat likely to look for another job if their employer required they work in person was similar

to the share who would look after a pay freeze (figure 14).

Job Changes

In the fourth quarter of 2021, 15 percent of workers said they were in a different job than they

were 12 months earlier. Most people who changed jobs said that their new job was better than

26

However, 16 percent of those working from home who said that they would prefer to work in person also said that they

would actively look for another job in this situation. This suggests that at least some of these individuals either were

actively looking irrespective of the work location, or they value being given the choice of where to work even if they

chose not to work from home.

27

The order of the pay cut and telework questions was randomized in the survey, as was the amount of the pay cut that

respondents were asked about.

Figure 14. Likelihood of looking for a new job (by required in-person work and pay cuts)

Percent

Not at all likelyNot that likelySomewhat likelyVery likely

Pay cut of 10 percent

Pay cut of 5 percent

Pay freeze

Report in person

22 23

23

18

32

13

29

32

32

40

39

20

8

45

16

7

Note: Among adults working for someone else who worked from home at least some of the time. Key identifies bars in

order from left to right.

28 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021

their old one. Over 6 in 10 people who

changed jobs said their new job was better

overall, compared with 1 in 10 who said that it

was worse.

Pay, opportunities for advancement, and

interest in the work were frequently seen as

better in the new job. Just over half of people

who changed jobs said that their pay and ben-

efits improved, compared with 20 percent who

said their pay was worse. Similarly, far more

people said that their work-life balance, oppor-

tunities for advancement, and interest in the

work improved than said these measures

declined (figure 15).

Of the characteristics considered, COVID-19

policies and exposure were the most likely to

be the same in the old and new jobs. Nearly

two-thirds (64 percent) of job changers said that COVID-19 policies and exposure were about the

same, while one-fourth said that they were better, and 11 percent said that they were worse.

28

Workers who experienced a layoff and changed jobs were less positive about their new positions

than other job changers.

29

Those who were laid off were substantially less likely than those not

laid off to say their new job was better overall.

30

They also were less likely to say that the pay and

benefits, opportunities for advancement, and interest in the job improved at their new position

(figure 16).

COVID-19 Precautions at Work

One factor in people’s decisions on whether to work and where to work is their perceptions of

workplace safety, including COVID-19 precautions. Employees mostly thought that their employers

were taking the right amount of precautions to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Seventy-seven per-

cent of employees said their employers were taking the right amount of precautions. Those who

28

Better COVID-19 policies could mean stricter or more lenient policies, depending on the preference of the respondent.

The survey did not define what better or worse policies meant.

29

Seven percent of adults said that they were laid off in the 12 months prior to the survey.

30

People’s perceptions of their old jobs likely also reflect the circumstances of their leaving, including negative feelings

from getting laid off. Moreover, while it is likely the laid-off worker is comparing their new job to the job they were laid off

from, it is also possible they had another job in-between.

Figure 15. Change in quality of job characteris-

tics after job change

BetterAbout the sameWorse

Work–life

balance

COVID-19 policies

and exposure

Physical

demands

Interest in

the work

Opportunities

for advancement

Pay or

benefits

Overall

10 28

62

51

44

29

41

20

15

48

3913

31

5713

256411

4043

16

Percent

Note: Among working adults whose main job was not

the same as it was a year ago. Key identifies bars in

order from left to right.

Employment 29