Equality and Human Rights Commission

Research report 119

Developing a national

barometer of prejudice

and discrimination

in Britain

Dominic Abrams

1

, Hannah Swift

1

and Diane Houston

2

1

University of Kent, Centre for the Study of Group

Processes

2

Birkbeck, University of London

October 2018

2

© 2018 Equality and Human Rights Commission

First published October 2018

ISBN 978-1-84206-763-5

Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series

The Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series publishes

research carried out for the Commission by commissioned researchers.

The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily

represent the views of the Commission. The Commission is publishing the report as

a contribution to discussion and debate.

Please contact the Research Team for further information about other Commission

research reports, or visit our website.

Post: Research Team

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Arndale House

The Arndale Centre

Manchester M4 3AQ

Email: [email protected]

Telephone: 0161 829 8500

You can download a copy of this report as a PDF from our website.

If you require this publication in an alternative format, please contact the

Communications Team to discuss your needs at:

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

3

Contents

Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6

Foreword from our Chief Executive ............................................................................ 7

Executive summary .................................................................................................... 9

1 | Introduction.......................................................................................................... 12

1.1 Why do we need a ‘barometer’ to measure prejudice and discrimination? . 12

2 | Designing the survey ........................................................................................... 15

2.1 Defining and measuring prejudice ............................................................... 15

2.2 Experiences and perceptions of prejudice .................................................. 17

2.3 Prejudice ..................................................................................................... 18

3 | Data collection ..................................................................................................... 21

3.1 Data collection ............................................................................................. 21

3.2 Interpretation and significance testing ......................................................... 21

Table 3.1 Experience of discrimination in the last year (per cent) summary

table ....................................................................................................... 22

4 | Survey findings .................................................................................................... 23

4.1 Equality endorsement ................................................................................. 23

4.2 The prevalence of experiences of discrimination ........................................ 24

Table 4.1 Prevalence of prejudice (per cent) for respondents with protected

characteristics (including boost data) ................................................................ 24

Table 4.2 Experiences of prejudice (per cent) based on age and sex by

country ....................................................................................................... 25

4.3 Areas of life in which people experience discrimination .............................. 26

4.4 Perceived seriousness of discrimination .................................................... 27

Figure 4.1 Perceived seriousness of discrimination ........................................ 27

4.5 Overtly positive and negative attitudes (feeling thermometer) .................... 29

Figure 4.2 Feelings towards people with each protected characteristic,

excluding those who belong to the target protected characteristic .................... 30

Table 4.3 Negative feelings expressed (%) towards people with particular

protected characteristics across England, Scotland and Wales ........................ 31

4.6 Stereotypes ................................................................................................. 32

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

4

Figure 4.3 Evaluations of each protected characteristic group on warmth and

competence ...................................................................................................... 33

4.7 Social distance ............................................................................................ 34

Figure 4.4 How comfortable would you feel if a member of the relevant group

was appointed as your boss? ............................................................................ 34

Figure 4.5 How comfortable would you feel if a member of the relevant

protected characteristic moved in next door to you? ......................................... 35

Figure 4.6 How comfortable would you feel if a person with one of the relevant

protected characteristics married one of your close relatives? .......................... 36

4.8 Equality endorsement for specific protected characteristics ........................ 37

Figure 4.7 Have attempts to give equal opportunities to the following groups

gone too far or not far enough? ......................................................................... 37

4.9 Intergroup contact ....................................................................................... 38

Figure 4.8 Percentage of respondents that have friendships with different

groups (excluding members of the target group) .............................................. 39

4.10 Motivation to control prejudice ................................................................. 40

4.11 Summary ................................................................................................. 41

5 | Insights from using the survey as a complete set of measures ........................... 43

5.1 Contrasting the experiences of two different protected characteristics ....... 44

Table 5.1 Case study measures of experiences of prejudice ......................... 44

5.2 Prejudiced attitudes ..................................................................................... 45

Table 5.3 Case study attitudes towards black people and disabled people with

a physical impairment ....................................................................................... 46

6 | Conclusions ......................................................................................................... 48

References ............................................................................................................... 52

Appendix A: Summary of measures ......................................................................... 55

Table A.1 Overview of measures of prejudice ................................................ 55

Appendix B: Questionnaire ....................................................................................... 58

Appendix C: Data collection approach ..................................................................... 73

C.1 Overview of the approach ........................................................................... 73

C.2 NatCen panel and ScotCen panel ............................................................... 74

C.3 Survey response to the NatCen and ScotCen panels ................................. 75

Table C.1 Survey response ............................................................................ 75

Table C.2 Sample profile of the NatCen panel ............................................... 76

Table C.3 Sample profile of the ScotCen panel .............................................. 77

Table C.4 Profile of protected characteristics within survey respondents ....... 78

C.4 PopulusLive panel ....................................................................................... 81

C.5 Weighting and analysis ............................................................................... 81

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

5

C.6 Coding of domains ...................................................................................... 83

Appendix D: Recommendations on usage of the survey .......................................... 84

D.1 Reliability and validity .................................................................................. 84

D.2 Survey approach ......................................................................................... 86

Tables and figures

Tables

Table 3.1 Experience of discrimination in the last year (per cent) summary table 22

Table 4.1 Prevalence of prejudice (per cent) for respondents with protected

characteristics (including boost data) ................................................... 24

Table 4.2 Experiences of prejudice (per cent) based on age and sex by country 25

Table 4.3 Negative feelings expressed (%) towards people with particular

protected characteristics across England, Scotland and Wales ........... 31

Table 5.1 Case study measures of experiences of prejudice ............................... 44

Table 5.3 Case study attitudes towards black people and disabled people with a

physical impairment .............................................................................. 46

Table A.1 Overview of measures of prejudice ...................................................... 55

Table C.1 Survey response ................................................................................... 75

Table C.2 Sample profile of the NatCen panel ...................................................... 76

Table C.3 Sample profile of the ScotCen panel .................................................... 77

Table C.4 Profile of protected characteristics within survey respondents ............. 78

Figures

Figure 4.1 Perceived seriousness of discrimination ............................................... 27

Figure 4.2 Feelings towards people with each protected characteristic, excluding

those who belong to the target protected characteristic........................ 30

Figure 4.3 Evaluations of each protected characteristic group on warmth and

competence .......................................................................................... 33

Figure 4.4 How comfortable would you be if a member of the relevant group was

appointed as your boss?....................................................................... 34

Figure 4.5 How comfortable would you be if a member of the relevant protected

characteristic moved in next door to you? ............................................ 35

Figure 4.6 How comfortable would you be if a member of the relevant protected

characteristic married one of your close relatives? ............................... 36

Figure 4.7 Equal opportunities for protected characteristic groups ........................ 37

Figure 4.8 Percentage of respondents that have friendships with different groups

(excluding members of the target group) .............................................. 39

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

6

Acknowledgements

This research was designed by Dominic Abrams, Hannah Swift and Diane Houston

at the University of Kent Centre for the Study of Group Processes and at Birkbeck,

University of London. The survey implementation and summary data were provided

by Hannah Morgan and Martin Wood at NatCen. We are grateful to collaborators at

the Centre for the Study of Group Processes, University of Kent for the early stages

of the development work and to Hazel Wardrop and Gwen Oliver at the Equality and

Human Rights Commission for advice and comments on earlier drafts of the report.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

7

Foreword from our Chief Executive

How many times in the past year has someone shown you a lack of respect because

of your race, impairment or sexual orientation? Would you feel comfortable if an

immigrant lived next door, or if your boss had a mental health condition? These are

some of the questions we asked in the first national survey of prejudice for over a

decade – and often the answers are surprising.

Almost 3,000 people across Britain talked to us about their experiences of prejudice

and their attitudes towards different groups. Forty-two per cent of all respondents

said they had experienced prejudice in the last year, with this figure being higher

among minority groups. This is a matter for concern, particularly as the survey also

found that some people think efforts to provide equal opportunities for particular

groups have ‘gone too far’.

Our work is framed by the principle that if everyone gets a fair chance in life, we all

thrive. We therefore need to understand the nature and extent of prejudice and

discrimination in Britain in order to tackle the barriers that are holding people back.

This requires having robust data on people’s attitudes towards others and on

people’s experiences of being disrespected, patronized, bullied or treated less well

because of their race, sex, impairment or any other protected characteristic. By

understanding the attitudes that underlie discrimination, we can ensure that efforts to

tackle it are more likely to hit the mark.

We are therefore calling for the UK Government to fund a regular national survey,

the findings of which would form a barometer showing the current state of prejudice

and discrimination in Britain. This report sets out a workable model that could be

carried forward by others. We also need social researchers, civil society and NGOs

to continue to develop and test this set of questions with other protected groups,

especially those who are hard to reach, to provide a comprehensive picture.

As part of our programme of work in this area, we have already examined the links

between attitudes and behaviours, and worked with partners to strengthen our

knowledge on ‘what works’ to tackle prejudice and discrimination. We will shortly be

launching our three-yearly review of the state of equality and human rights in Britain.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

8

‘Is Britain Fairer? 2018’ will be an important counterpart to this survey, allowing us to

see where prejudiced attitudes towards certain groups may be holding them back in

life.

Taken together, these reports are a significant contribution to our bank of evidence

on how people in Britain live and work together. We will use this data in our own

work, and we hope policy-makers in general will use it in theirs – in order to drive

lasting change. Britain has a proud history of tackling intolerance and prejudice and

we must ensure that we continue to lead the way as we leave the European Union.

We believe that justice, freedom and compassion should be the traits that define our

nation into the future.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

9

Executive summary

This is the first national survey of prejudice for over a decade. It measures prejudice

and discrimination in Britain experienced by people with a wide range of protected

characteristics: age, disability, race, sex, religion or belief, sexual orientation,

pregnancy and maternity, and gender reassignment.

Our report demonstrates the value of using a national survey of this type to measure

prejudice and discrimination in Britain and to set out a benchmark for future surveys.

The purpose of this research is to help establish a national ‘barometer’ for monitoring

changes in the attitudes and experiences of the general population.

We were commissioned by the Equality and Human Rights Commission to design

and run a national survey of prejudice, using a consistent set of measures across a

range of protected characteristics. We surveyed 2,853 adults in Britain using the

NatCen Panel surveys and carried out an additional survey to target minority groups

that may otherwise not be well represented in the survey.

Our approach provides new insights into the form and prevalence of prejudice and

discrimination in Britain. Measuring these issues in a consistent way across

protected characteristics groups and across England, Scotland and Wales, gives us

a uniquely recent and comparable overview. It enables us to look across a range of

measures to paint a meaningful picture of the prejudice affecting a particular

protected characteristic, rather than looking at individual measures on their own.

Although it does not yet provide a picture of prejudice and discrimination for all

protected characteristics – which would require a larger and further-developed

survey – it sets out a workable model for a future national instrument for monitoring

these issues in Britain.

This report provides an overview of what we have found out about people’s

experiences and expressions of prejudice in Britain.

Experiences of prejudice and discrimination

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

10

42% of people in Britain said they had experienced some form of prejudice in

the last 12 months.

Data from the combined representative panel survey and boost sample data

indicated that experience of prejudice was higher in minority groups. This

should be interpreted with some caution because of methodological

differences from the main survey. In the last year:

- 70% of Muslims surveyed experienced religion-based prejudice

- 64% of people from a black ethnic background experienced race-based

prejudice

- 61% of people with a mental health condition experienced impairment-

based prejudice, and

- 46% of lesbian, gay or bisexual people experienced sexual orientation-

based prejudice.

Ageism can be experienced by people at any age. In line with previous

research, a higher proportion of British adults reported experiencing prejudice

based on their age (26%) than on any other characteristic.

Attitudes

Nearly three-quarters of people in Britain (74%) agreed that there should be

equality for all groups in Britain, but one in ten (10%) people surveyed

disagreed.

More people expressed openly negative feelings towards some protected

characteristics (44% towards Gypsies, Roma and Travellers, 22% towards

Muslims, and 16% towards transgender people) than towards others (for

example, 9% towards gay, lesbian or bisexual people, 4% towards people

aged over 70, and 3% towards disabled people with a physical impairment).

A quarter expressed discomfort with having a person with a mental health

condition as their boss (25%) or as a potential family member (29%). Around

one-fifth of respondents said they would feel uncomfortable if either an

immigrant or a Muslim person lived next door (19% and 18% respectively),

and 14% said they would feel uncomfortable if a transgender person lived

next door.

Around a third of British adults felt that efforts to provide equal opportunities

had gone ‘too far’ in the case of immigrants (37%) and Muslims (33%). In

contrast, nearly two-thirds thought that such efforts had ‘not gone far enough’

for people with a mental health condition (63%) or people with a physical

impairment (60%).

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

11

Developing a national barometer

We have identified some examples of how this survey generates useful insights

when used as a complete set of measures:

People’s perceptions of the seriousness of discrimination in Britain in relation

to different protected characteristics did not match levels of personal

experiences of discrimination. For example, more than half (54%) thought that

the issue of discrimination based on age was not at all or only slightly serious,

despite more British adults reporting experiences of prejudice based on their

age (26%) than any other protected characteristic.

People’s resistance to improving equal opportunities was greatest towards

those groups that they considered to be less ‘friendly’ and more ‘capable’

(such as Muslims and immigrants) and least in relation to those they

considered less ‘capable’ but more ‘friendly’ (such as disabled people).

Prejudices are likely to be quite specific, and there are differences in the ways

that people express their prejudices towards people with different protected

characteristics. Although similarly low numbers of people expressed negative

feelings towards disabled people with a physical impairment and those with a

mental health condition, fewer people were comfortable with the idea of

having a person with a mental health condition as their boss or neighbour

compared to a disabled person with a physical impairment.

The form and prevalence of prejudice may differ across regions of Britain. For

example, the percentage of respondents who expressed negative feelings

towards Muslims, immigrants and Gypsies, Roma and Travellers was lower in

Scotland than in England.

Our report identifies a set of measures that can be repeated regularly to create a

consistent evidence base on the form and prevalence of prejudice and discrimination

in Britain. The survey can be adapted and extended to assess specific additional

aspects of prejudice and discrimination, as well as affected groups and areas of life

not covered in this report. The ongoing development of the survey measures is

essential to ensure it remains an accurate, relevant and useful tool for seeking to

understand prejudice and discrimination in Britain.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

12

1 | Introduction

This report presents evidence from the first national survey since 2006 to measure

prejudice and discrimination in Britain using a consistent set of measures across a

range of protected characteristics.

An important and distinctive feature of the survey is that it brings together a set of

measures both of people’s experiences of prejudice and of people’s attitudes. This

provides a more comprehensive picture of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

than single measures allow, and helps us to understand the impact of prejudice on

people’s lives.

A second important feature of the survey is that it measures these factors across

multiple protected characteristics. This enables us to understand how people’s

prejudiced attitudes and experiences of discrimination differ for different protected

characteristics, although we were not able to measure all aspects of prejudice across

all nine protected characteristics set out under the Equality Act 2010. The survey has

been designed to be easy to use and to adapt for different protected characteristics.

This report demonstrates the use and value of a survey of this kind and provides a

benchmark for assessing the prevalence of prejudice in Britain against which future

evidence can be collected and compared to form a national ‘barometer’ of the

changing landscape of prejudice and discrimination in Britain.

1.1 Why do we need a ‘barometer’ to measure prejudice and

discrimination?

To tackle prejudice and discrimination faced by people because they share a

particular protected characteristic, we first need to understand the levels of prejudice

and discrimination in Britain and the forms they take. These forms of prejudice and

discrimination may differ depending on which protected characteristics are involved.

1

1

For an overview of hate crime legislation in Britain, see Walters, Brown and Wiedlitzka (2017).

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

13

The Equality and Human Rights Commission (‘the Commission’) was established

under the Equality Act 2006 to work towards the elimination of unlawful

discrimination, to promote equality of opportunity, and to protect and promote human

rights. The Equality Act 2010 provided a single legal framework to tackle

disadvantage and protect people from discrimination. The Act prohibits

discrimination against someone because of their perceived age, sex, race,

2

disability, religion or belief (including lack of belief), sexual orientation, for being

pregnant (or having a baby), being married or in a civil partnership, or being

transgender.

In 2016, a review of the available data sources and indicators of prejudice and

discrimination used in the last ten years identified a lack of up to date, consistent and

comparable measures for understanding the prevalence of prejudice in Britain

(Abrams, Swift and Mahmood, 2016). The review revealed that current evidence

from Britain does not allow meaningful comparisons across protected characteristics

or make it possible to comment on the rate of changes in the nature and extent of

prejudice and discrimination.

This research provides a set of measures that can be used by the Commission and

others to capture experiences of discrimination across different areas of life (EHRC,

2017), and that provides a picture of prejudice and related attitudes held towards

different social groups in society. The survey can be used and extended by others to

establish comparable evidence with which to regularly monitor national-level

changes in prejudice and discrimination over time. Regularly collected comparable

evidence of this type would form a national ‘barometer’ of prejudice and

discrimination in Britain.

The set of indicators to measure prejudice used in this survey is based on social

psychological theories of prejudice. It draws on questions used in an initial

benchmarking study which was commissioned as preparation for the establishment

of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, examining prejudices affecting six

protected characteristics in 2005 (Abrams and Houston, 2006). We also drew on a

database of items identified in the 2016 review (Abrams et al., 2016). The theory and

measurement issues underpinning the current research, as well as implications for

interventions, are extensively considered in the Commission’s 2010 report

‘Processes of Prejudice’ (Abrams, 2010). The set of measures in the barometer are

outlined in chapter 2. The set is not exhaustive but provides sufficient breadth to

capture core features of prejudice. What is new in this research is that we are using

2

The protected characteristic of race refers to a group of people defined by their race, colour and

nationality (including citizenship), ethnic or national origins.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

14

this set together for the first time since Abrams and Houston (2006), to capture

experiences and expressions of prejudice towards most of the protected

characteristics. We are measuring these across the same representative sample of

respondents (as well as additional samples of people with particular protected

characteristics that tend to be under-represented in national surveys). This enables

us to compare and draw conclusions about the state of prejudice and discrimination

affecting many of the protected characteristics across much of Britain.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

15

2 | Designing the survey

2.1 Defining and measuring prejudice

There are many definitions of prejudice (for example, see Nelson, 2009). The

definition we use here captures its primary feature – a bias that is based on whether

or not people share membership of particular social categories with each other.

Specifically, we define prejudice as:

‘Bias that devalues people because of their perceived membership of a social

group.’ (Abrams, 2010)

The term ‘bias’ refers to a preference for or against, but either direction can have

harmful consequences. The term ‘perceived membership’ underlines the importance

of perception as distinct from any objective information – that is, when people judge

or act towards other individuals based on assumptions about differences between

groups, their application of these assumptions may well be misguided. Biases and

perceptions are not always intentional, easy to recognise or control, but this does not

reduce the need to establish their presence and impact.

People may show prejudiced attitudes in a variety of forms. The most obvious are

direct and explicit statements of dislike or abuse, but there are also indirect and more

subtle forms such as objections to equal rights for particular groups or patronising or

‘benevolent’ stereotypes about particular groups. Even a bias, or preference, in

favour of someone based on their perceived group membership can be harmful to

people from other groups because it might indirectly imply lower importance, value,

status or level of deservingness to those other groups.

Prejudice has been measured in a variety of large surveys, such as research for the

Cabinet Office Equalities Review (Abrams and Houston, 2006), surveys by Stonewall

(2012; Cowan, 2007), the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey (SSAS) 2006 and 2010

and the British Social Attitudes Survey (BSAS) 2008-14 (NatCen, undated).

However, measures vary across different types of research, for different protected

characteristic groups, across regions of Britain and are not all conducted regularly

enough to get a consistent or comparable picture of prejudice in Britain.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

16

Some key components of prejudice are routinely studied by social psychologists.

Some feature occasionally in national surveys but rarely appear together.

These are:

views about equality and equal opportunities for different protected

characteristics

the perceived seriousness of the issue of discrimination against different

groups can provide insight into awareness and perceptions of the problem

directly expressed positive and negative attitudes towards the group

(measured using a ‘feeling thermometer’)

stereotypes of warmth and competence that reflect the core elements of

people’s understanding of how groups compare with one another across

society

emotions that people feel towards members of different social groups

willingness to maintain ‘social distance’ or engage in social contact with

members of other groups in important contexts

the extent of meaningful social contact that actually exists between members

of different groups, and

norms and the perceived social acceptability of expressing prejudiced

attitudes.

All of these components are well-suited for use in quantitative surveys and we have

included them in the survey.

3

This survey focused on aspects of prejudice that people are able to recognise or

control. There are other forms of prejudice that are not easily measured by surveys,

and other methods may be better suited to capture these. For the most part these

are not appropriate for large scale evaluation and benchmarking.

3

For an in-depth review of theories of prejudice each measure pertains to, please see Abrams (2010)

and Abrams et al. (2016). Other measures that are used in prejudice research include: how we

categorise one another; values; political preferences; personality characteristics; their use of various

forms of media; their perceptions that particular groups pose a threat to the livelihood or way of life of

others; their exposure to certain forms of influence; and their willingness to engage in action to

support disadvantaged groups (see Abrams and Houston, 2006). Although all of these are highly

relevant to why people are prejudiced (Abrams, 2010), they are beyond the scope of the current work

wherein we concentrated on measuring prejudice itself.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

17

We briefly introduce each component included in the survey and provide a summary

of the set of the measures we have used in appendix table A.1. The specific items

are provided in chapter 4.

2.2 Experiences and perceptions of prejudice

Experiences of prejudice and discrimination

To measure experiences of prejudice we used a measure developed in previous

research with Age UK (see Abrams, Eilola and Swift, 2009; Ray, Sharp and Abrams,

2006), the Cabinet Office Equalities Review (Abrams and Houston, 2006) and the

2008 European Social Survey (see Bratt, Abrams, Swift, Vauclair and Marques,

2017). We conducted further pilot work for this survey to ensure that it was well-

understood by respondents with different protected characteristics. We used a

general measure to ask whether people have experienced prejudice against

themselves: ‘In the last year, has anyone shown prejudice against you or treated you

unfairly because of your (list of protected characteristics).’

Prejudice can be expressed and experienced in different ways. For example,

sometimes it may be directly confrontational but it can also be more patronising or

passive (for example, neglectful). Therefore, if people report they had experienced

any prejudice, we asked them two further questions (see survey item summary in

appendix A) to explore what type of prejudice they had experienced.

Discrimination can be experienced in different areas of life. Some areas of life may

pose greater risks of discrimination for groups with a particular protected

characteristic than others. Therefore, we asked a further question about the areas of

life in which the experiences of prejudice occurred (Q1a).

Importance attached to equality and perceived seriousness of prejudice

We asked respondents to say how much importance they attached to equality, which

can then be compared with their responses to other questions about their attitudes

towards people with particular protected characteristics. In principle, we would

expect most people to place equality very high on their list of value priorities.

Similarly, they might be expected to view discrimination on the basis of all protected

characteristics as equally serious (Abrams et al., 2015), and we captured this by

asking people how serious they felt discrimination was when it was directed at

people with particular protected characteristics.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

18

These questions give us insight into whether people apply different standards when

thinking about different groups, for example, by endorsing greater protection of

equality or by regarding prejudice as a less serious problem in some cases rather

than others.

Comparing responses from these two questions with the responses from the

experience of prejudice questions provides important information about whether the

experiences of people with particular protected characteristics match the general

population’s perceptions of how serious a problem prejudice against these groups is.

For example, if very few people regard prejudice toward a certain group as being

serious, but many members of that group have experienced prejudice, this could

indicate that people do not attach much importance to the prejudice (for example,

because it is seen as harmless), or aren’t aware of or don’t recognise the treatment

as being based in prejudiced or discriminatory attitudes.

2.3 Prejudice

Feeling thermometer

To measure how directly people are willing to admit to feeling negatively about a

particular group we based a question on the so-called ‘feeling thermometer’ that has

been used in previous work (see Abrams and Houston, 2006; Pettigrew and

Meertens, 1995). This is sometimes presented as a picture of a thermometer

(ranging from 0 to 100 degrees), on which people are asked to indicate how they feel

toward a social group by marking a position on the temperature scale. The measure

used in the present research is a version on a five-point scale that asks people, even

more directly, how positive or negative they feel about different groups in Britain.

Stereotypes and associated emotions

A stereotype is a shared image of a social category or group that is applied and

generalised to members of the group as a whole regardless of their individual

qualities. It may or may not be accurate, and stereotypes can sometimes be an

important source of prejudice and discrimination because of the assumptions they

reinforce and the feelings they arouse.

We used the Stereotype Content Model (Fiske et al., 2002) to examine the two

central elements of stereotypes about some minority groups – their warmth and their

competence. Different evaluations of warmth and competence tend to imply different

emotions towards a given group. These emotions include pity (linked to high warmth

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

19

and low competence), admiration (high warmth and high competence), contempt and

anger (low warmth and low competence) and envy (low warmth and high

competence) (Cuddy, Fiske and Glick, 2007). The model has received support from

numerous national and international studies involving a very large number of

different groups (Cuddy et al., 2009). Based on the model we also included

perceptions of whether the groups are ‘moral’ and whether they are ‘receiving

special treatment’, and the emotions of fear and disgust. These stereotypes and

emotions are measured in a way that is slightly less direct than the feeling

thermometer (asking how the respondent thinks other people view the groups, not

how the respondent views them). This is a way of reducing people’s concerns about

the social appropriateness of stating that they hold a stereotyped view themselves.

But because most people assume others (broadly) share their own views, this is still

quite a good measure of stereotypes across society (Robbins and Krueger, 2005).

Social distance

Following a long tradition of research on prejudice we included measures of ‘social

distance’, the extent to which people would be comfortable with various degrees of

closeness of relationship with members of different groups. This well-established

measure is important because it reflects people’s actual behavioural inclination to

engage with people with particular characteristics. We asked respondents to what

extent they would feel comfortable if a member of the relevant group was their boss,

moved in next door to them, or married (or formed a civil partnership) with a close

relative (see tables E14-16).

Intergroup contact

The extensive literature on intergroup contact (see Pettigrew, 1998, and Pettigrew

and Tropp, 2006 for a meta-analysis of over 500 studies) demonstrates that contact

between members of different groups fosters positive intergroup attitudes if the

contact also involves similarity, common goals, institutional support and equal status.

Research suggests that a critical type of contact is friendship, more specifically the

number of friends we have who belong to social groups different from ourselves. If

we are friends with people from a different social group we are less likely to sustain

prejudicial attitudes towards their group. Friendship builds trust and reduces anxiety

about interacting with people from the other group. It also encourages us to take

similar perspectives and increases our empathy with other members of their group.

Using the measures we developed for research with Age UK and European Social

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

20

Surveys we asked respondents about the number of friendships they have with

people who share different protected characteristics.

Subtle prejudice

An item that is partly a measure of ‘modern’ or ‘subtle prejudice’ is whether people

think equality policies to support a particular group have gone too far. Previous

research has shown equality is a principle that almost everyone endorses very

strongly. Given that equality can only be achieved, not surpassed, people who think

equality has gone too far are indirectly expressing prejudice or resentment towards

that group. We included two questions on subtle prejudice in the survey: whether

attempts to give equal opportunities to different groups in society have gone too far,

or not far enough.

Motivation to control prejudice

Finally, expressions of prejudice may be affected by one’s own concerns or by social

pressures. To the extent that people feel they do not want to, and do not want to be

seen to express prejudice, this promotes a social norm that should gradually make

prejudice less likely to emerge or spread. The extent to which such norms are taken

on as personal standards for behaviour can therefore be a useful index of progress

in tackling prejudice generally. In this research we use measures of ‘internal and

external control’ over prejudice to assess these factors, asking people to what extent

they act in a non-prejudiced way because it is important them, and to what extent

they do so to avoid disapproval from others.

All the items included in the survey, and surveys in which the items have been

fielded previously are included in appendix table A.1.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

21

3 | Data collection

3.1 Data collection

The aims of the survey were to gain a representative picture of prejudice and

discrimination in Britain, provide insight into the experiences of some relatively small

protected characteristic population subgroups, and look at findings separately for

England, Scotland and Wales. A full overview of the measures included in the survey

can be found in Appendices A and B.

To achieve these aims, the study collected data using the random probability NatCen

and ScotCen Panels (which use a sequential online and CATI data collection

approach) in combination with the non-probability PopulusLive Panel (which uses

online data collection).

We used the PopulusLive panel to provide larger samples of some specific protected

characteristic groups – black British people, lesbian, gay and bisexual people,

Muslims, and people with mental health conditions – and to boost the size of the

sample available in Wales. Non-probability panels provide an effective means of

accessing small incidence populations that would be very costly to achieve via

probability approaches, although findings should be considered indicative only and

treated with caution.

As described in appendix C, probability and non-probability data have been brought

together in this study to provide some indicative findings for these small incidence

groups. In addition, the probability ScotCen panel was used to provide a sample of

sufficient size for robust analysis in Scotland.

3.2 Interpretation and significance testing

Most of the findings in this report refer to the random probability NatCen and

ScotCen panels. Where findings relate to data from the non-probability source, this is

clearly stated. Statistical testing was applied to the findings that used the probability

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

22

samples and differences discussed in the text are significant at the 95% level unless

otherwise stated.

Table 3.1 illustrates the 95% confidence intervals for the key measure of

experiences of discrimination.

Where estimates use data from the non-probability panel boosts for specific

protected characteristics, these estimates should be considered indicative only and

treated with caution. The low incidence of these populations coupled with the non-

probability nature of the sample mean we cannot know how representative these

samples are of the actual population subgroups.

In order to provide a sufficient number of cases for analysis of people in Wales, a

non-probability boost was matched to the probability sample and a weight

developed. For the English and Scottish analysis, only data from the probability

panels were used. Whilst analysis can be carried out within the resulting Welsh

sample, the different methodologies used for cases in Wales mean that direct

comparisons should not be made between England and Wales (comparisons

between England and Scotland can be made).

Table 3.1 Experience of discrimination in the last year (per cent) summary

table

Sex (male or

female)

Age

Race or

ethnicity

Any physical or

mental health

condition you

may have

Sexual

orientation

Religion or

religious beliefs

Experienced

any kind of

discrimination

Experienced

discrimination

in the last year

based on…

Estimate

22

26

16

16

7

12

42

Standard error

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

95%

confidenc

e interval

Lower

19

23

14

14

5

10

39

Upper

24

28

18

18

8

14

45

Did not

experience

discrimination

in the last year

based on…

Estimate

78

74

84

84

93

88

58

Standard error

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

95%

confidenc

e interval

Lower

76

72

82

82

92

86

55

Upper

81

77

86

86

95

90

61

Total

Total

100

100

100

100

100

100

100

Unweighted base

2170

2171

2170

2167

2171

2170

2170

Weighted

base

2172

2172

2171

2172

2171

2172

2172

Base: All GB adults aged 18+ (data from NatCen panel)

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

23

4 | Survey findings

In this section we report the main findings across the representative sample, and in

some cases from the non-probability boost samples, for individual measures of

prejudice. Statistical testing was applied to the findings that used the probability

samples and differences discussed in the text are significant at the 95% level.

4.1 Equality endorsement

‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following

statement: “There should be equality for all groups in Britain.”’

1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’

‘don't know’ and ‘prefer not to say’.

Three-quarters of British adults (74%) agreed or strongly agreed that there should be

equality for all groups in Britain, while 15% neither agreed nor disagreed and 11%

disagreed or strongly disagreed (see appendix table E.1). This evidence is quite

encouraging in terms of the implied support for policies designed to address

inequality. This measure should be viewed in the light of people’s views on the

seriousness of discrimination directed at people with particular protected

characteristics, although this comparison was not part of analysis carried out for this

report.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

24

4.2 The prevalence of experiences of discrimination

‘Thinking about your personal experiences over the past year, how

often has anyone shown prejudice against you or treated you

unfairly because of [protected characteristic]?’

‘Almost all of the time’; ‘a lot of the time’; ‘sometimes’; ‘rarely’; ‘not in

the last year’, ‘does not apply’

('don't know' and 'prefer not to say' initially hidden).

(‘don’t know’ and ‘prefer not to say’ initially hidden).

Prejudice had been experienced by two in five people (42%) because of their

membership of at least one of the protected characteristics. Ageism can be

experienced by people at any age, and, in line with previous research (Abrams and

Houston, 2006; Abrams, Russell, Vauclair and Swift, 2011), a higher proportion of

adults reported experiencing prejudice based on their age (26%) than any other

characteristic, followed by sex (22%). Appendix table C.5 shows the proportion of the

population who experienced prejudice based on different characteristics, and the

proportion of people who have experienced any type of discrimination in the last

year.

To explore the experiences of minority groups, we boosted the size of the sample

available for analysis using a non-probability panel. Table 4.1 shows that, within

each protected characteristic, experiences of prejudice are very prevalent, for

instance, 70% of Muslims reported that they had experienced religion-based

prejudice in the last year, and 46% of people belonging to a sexual orientation

minority experienced homophobic prejudice in the last year. These estimates should

be treated with caution; given the way the sample was gathered and the small size of

these populations we cannot know how representative these samples are of the

actual population subgroups. Nonetheless, the reported levels of experience are

notably high given that people in the boost samples agreed to participate without

knowing ahead of time what the content of the survey would be. They did not choose

to participate because of any particular interest in responding to questions about

prejudice.

Table 4.1 Prevalence of prejudice (per cent) for respondents with protected

characteristics (including boost data)

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

25

Protected

characteristic group

Black ethnic

background

(%)

Mental health

condition

(%)

Gay, lesbian or

bisexual

(%)

Muslim

(%)

Type of prejudice

Race or

ethnicity

Physical or mental

health condition,

impairment or

illness

Sexual

orientation

Religion

Any prejudice

experienced in the

last year

64

61

46

70

Unweighted base (no

weighting applied)*

210

659

450

294

* This table is based on all respondents from each protected characteristic across the non-

probability boost sample and the NatCen panel. Therefore, no weighting is applied and the findings

are indicative only.

Table 4.2 below shows a comparison between countries, using the NatCen panel

data and boost sample for Wales to capture sufficient numbers from Wales. The

most reliable data are for sex and age because these are similarly distributed in the

three countries. We do not find any statistically meaningful differences in the

prevalence of experiences of sexism or ageism between the three countries.

However, summarising across countries, women report experiencing sexism

substantially more than men do (30% compared with 13%), and those under 35 are

more likely to experience age prejudice than are those aged 35 to 54 or those aged

over 55 years (39% compared with 22% and 20% respectively).

Table 4.2 Experiences of prejudice (per cent) based on age and sex by

country

England

Scotland*

Wales**

Total***

Female

Experienced prejudice in the

last year because of your sex

30

29

28

30

Unweighted base*

1,078

430

335

1,229

Male

Experienced prejudice in the

last year because of your sex

14

16

19

13

Unweighted base*

817

405

301

943

Base: All GB adults aged 18+

* ScotCen and NatCen panel cases

** Combines NatCen panel and boost data for Wales

*** NatCen panel data only – no Scottish or Welsh boost

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

26

England

Scotland*

Wales**

Total***

18 to 34 years

Experienced prejudice in the

last year because of your age

40

38

47

39

Unweighted base

312

105

140

352

35 to 54 years

Experienced prejudice in the

last year because of your age

22

22

27

22

Unweighted base

688

295

212

789

55+ years

Experienced prejudice in the

last year because of your age

20

18

30

20

Unweighted base

883

433

284

1,019

Base: All GB adults aged 18+

* ScotCen and NatCen panel cases

** Combines NatCen panel and boost data for Wales

*** NatCen panel data only – no Scottish or Welsh boost

4.3 Areas of life in which people experience discrimination

If respondents said they had experienced any prejudice in the last year, we then

asked them:

‘In which area of your life did the experience of prejudice occur in

relation to your age, sex (male or female), race or ethnicity, any

physical or mental health condition, impairment or illness you may

have, sexual orientation, religion or religious beliefs?’

‘access to or experience of education or training’

‘access to employment or experience at work’

‘access to or experience of health or social care’

‘access to or experience of the police or criminal justice system’

‘access to housing or benefits’

‘access to or experience of public transport’

‘as a consumer (using shops or services)’

‘experience of a social situation, or with close peers or friends’

‘another area’

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

27

The areas of life selected were not intended to cover every eventuality but were

derived from the domains in the Equality and Human Rights Commission’s

measurement framework for equality and human rights and analysis of previous UK

research on people’s experiences of prejudice (Abrams et al., 2016).

Sixty per cent of those who had experienced prejudice said it arose in social

situations or with close peers or friends, and nearly half (46%) had experienced

prejudice or discrimination in employment or at work. Over a third (35%) had

experienced it as a consumer, dealing with shops or services, while a quarter (25%)

had done so when using some form of public transport (see table E.6 in appendix).

Further analysis will be needed to know whether these differences are due to a

person’s greater likelihood of having contact with or experiencing an area of life, or if

they reflect genuine differences in the likelihood of a person with a particular

protected characteristic experiencing prejudice when in that setting. The survey did

not ask separately about online experiences, but this may be an important additional

area to consider in future rounds of the survey.

4.4 Perceived seriousness of discrimination

‘In this country nowadays, how serious is the issue of discrimination

against people because of each of the following [protected

characteristics listed]?’

‘not at all serious’, ‘slightly serious’, ‘somewhat serious’, ‘very serious’

or ‘extremely serious’

‘don't know’ and ‘prefer not to say’.

Figure 4.1 shows the percentage of people across Britain who reported the issue of

discrimination to be very or extremely serious, somewhat, or only a slight or non-

serious issue in the case of each protected characteristic. Note that we have

included all respondents in this analysis as the aim is to capture the overall

prioritisation of tackling prejudices across society. Future work should consider how

these perceptions differ depending on people’s membership of different protected

characteristics.

Figure 4.1 Perceived seriousness of discrimination

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

28

54

48

30

35

33

43

46

52

70

65

67

57

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Age Gender Race or ethnic

background

Religion or

religious beliefs

Physical or

mental health

condition,

impairment or

illness

Sexual

orientation

%

Base: all GB respondents aged 18+

n= 2180

NET: not at all/slightly NET: somewhat/very/extremely

Discrimination was more likely to be regarded as a somewhat, very or extremely

serious issue when it affected race or ethnicity (70%), physical or mental health

impairment (67%) and religion (65%). But even with these forms, around a third of

respondents viewed discrimination not to be a serious issue (race, 30%; physical or

mental health impairment, 33%; religion, 35%).

Perceptions of the seriousness of discrimination directed at people with particular

protected characteristics did not align with people’s personal experiences of

discrimination, highlighting that people have different levels of awareness of

discrimination. It is possible that people overestimate the frequency and seriousness

of discrimination towards some protected characteristics, while underestimating it for

others. If people do not regard prejudice toward a certain group as being serious, but

many members of that group have experienced prejudice, this could either arise

because those people do not attach much importance to the prejudice (for example,

because it is seen as harmless), or because people are unaware that treatment of

the group is based on prejudicial biases. A question for future research and policy is

whether more needs to be done to expand people’s understanding of the

seriousness of prejudice and discrimination, including the societal implications as

well as the personal implications.

An important area for future analysis of this data is the relationships between how

seriously people view different types of prejudice and their support for equality for

people that share particular protected characteristics.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

29

4.5 Overtly positive and negative attitudes (feeling thermometer)

‘In general, how negative or positive do you feel towards each of the

following groups in [Britain]?’

1 ‘very negative’ to 5 ‘very positive’

‘don’t know’; ‘prefer not to say’.

It is important not to interpret feeling thermometer data at face value. The feelings

are not ‘absolute’ in any sense but reflect how respondents feel about different

groups relative to others.

The feeling thermometer question was asked about the following protected

characteristic groups: men, women, people aged over 70, people aged under 30,

black people, Muslims, immigrants, Gypsy, Roma and Travellers, gay, lesbian and

bisexual people, transgender people and disabled people (physical impairment and

mental health). The measure tells us about the extent to which different groups in

society may be the target of overtly negative attitudes. But it also sheds light on the

presence of more implicit forms of bias – the relative positivity to some groups rather

than others. The thermometer measure also reflects the social conventions

governing whether people feel able to express antipathy openly towards particular

groups. The thermometer gives us insight into which groups are most likely to be

vulnerable to expressions of direct hostility, but it is less sensitive to other forms of

discrimination which can be directed at groups that attract ‘positive’ evaluations,

such as older people, women and disabled people with physical impairment.

A simple way to illustrate the findings is the percentage that expressed a negative,

neutral or positive feeling about the minority categories. This is depicted in figure 4.2,

which excludes the respondents who themselves were a member of the relevant

group (for example, we show men’s attitudes towards women and women’s attitudes

towards men; we show the attitude of non-Muslims towards Muslims, etc.).

Developing a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

30

Figure 4.2 Feelings towards people with each protected characteristic, excluding those who belong to the target

protected characteristic

Base – all GB adults, excluding those belonging to the target group. Unweighted n:

Men 1,231; women 945; people aged over 70 1,852; people aged under 30 1,979; people with a mental health condition 1,957; disabled

people with a physical impairment 1,580; black people 2,129; Gypsy, Roma and Travellers 2,169; Muslims 2,123; immigrants 2,171;

people who present their gender differently to the one they were assigned at birth 2,171; gay, lesbian and bisexual people 2,034.

6

2

4

6

5

3

5

44

22

27

16

9

44

38

39

43

44

38

45

36

44

39

47

47

50

60

57

51

51

59

50

20

35

34

37

44

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Men Women People Aged

Over 70

People aged

under 30

People with a

mental health

condition

Disabled

people with a

physical

impairment

Black PeopleGypsy, Roma

and

Travellers*

Muslims Immigrants* People who

present their

gender

differently to

the one they

were

assigned at

birth

Gay, lesbian

or bisexual

people

%

Net Negative Neither negative nor positive Net Positive

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Towards a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

31

Openly positive feelings were expressed by more than half of respondents towards

many protected characteristics. Gypsy, Roma and Travellers were the only protected

characteristic group for which the most frequent response was openly negative

(44%). Fewer than half of respondents expressed positive feelings towards Muslims,

immigrants, gay, lesbian or bisexual people, and transgender people, and for these

protected characteristics the most common response was neutral.

When respondents express a neutral view it may reflect genuinely that they feel

neither positive nor negative feelings toward the group. But it is also possible that

they feel ambivalent – positive about some members of the group, but negative

about other members. A third possibility is that a neutral response reflects negative

feelings that people feel inhibited from expressing, and so hide behind ‘no opinion’

responses (Berinsky, 2004). Therefore, the balance between neutral and positive

evaluations is informative.

There are also differences in feeling thermometer scores between nations. Table

4.3, shows the percentage of all respondents from the NatCen panel and the Welsh

boost sample who expressed negativity towards the different groups.

Table 4.3 Negative feelings expressed (%) towards people with particular

protected characteristics across England, Scotland and Wales

Scotland %

England %

Wales* %

Men

4

5

3

Aged over 70

4

4

3

Women

2

2

2

Black people

4

5

6

People who present their gender

differently to the one they were

assigned at birth

15

16

19

Muslims

15

22

29

People with a mental health

condition

4

5

5

Gay, lesbian or bisexual people

8

9

9

Immigrants

20

27

31

Disabled people with a physical

impairment

2

3

3

Gypsy, Roma and Travellers

31

44

42

People aged under 30

5

6

7

Unweighted base

837

1903

636

* Note: Base includes all respondents (including boost in Wales)

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Towards a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

32

It is noticeable that the percentage of respondents who express negativity is lower in

Scotland than in England or Wales in relation to feelings towards Muslims,

immigrants and Gypsy, Roma and Travellers. Further analysis could illuminate the

reasons for this finding, and it should be interpreted in the context of, amongst other

factors, the extent to which opportunities for contact between these minorities and

other groups exist and occur in these different regions.

4.6 Stereotypes

‘To what extent are people viewed in the following ways:

As capable

As friendly’

1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’

'don't know' and 'prefer not to say'.

‘don't know’ and ‘prefer not to say’.

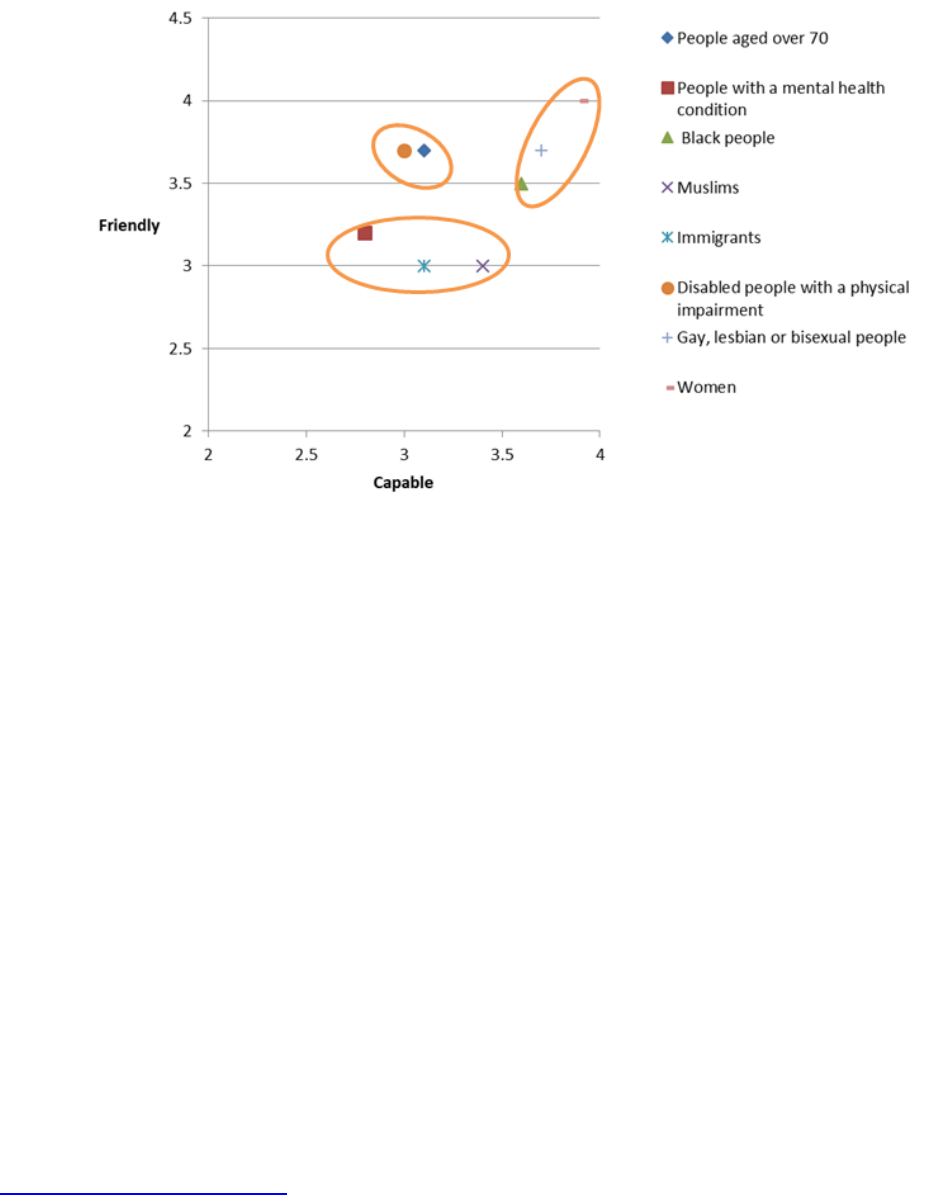

The classification of several groups along dimensions of competence and warmth

has been examined in several countries around the world (Fiske et al., 2002; Cuddy

et al., 2009). Figure 4.3 shows evaluations of groups along these two dimensions.

Whether a group is viewed as capable or friendly can affect the form of prejudice that

emerges towards them. Because of this, it is important to consider these stereotypic

evaluations relative to one another. For ease of comparison we have grouped

characteristics that tend to share common stereotypical characteristics. This is

simply for visual purposes and is not a statistically based grouping. According to this

previous research, those viewed as being relatively high in competence (capability)

and warmth (friendliness) are likely to be viewed with admiration. Here we find

women were viewed most positively as high in competence and warmth, followed by

gay, lesbian and bisexual people and black people.

Groups that are only evaluated highly on one dimension are typically perceived less

favourably. People over 70 and disabled people with a physical impairment are

perceived to be relatively warm but relatively less capable. These groups are likely to

be viewed with pity. Immigrants, Muslims and people with a mental health condition

are all perceived as the least warm groups, but they differ in terms of perceived

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Towards a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

33

competence. Groups that are perceived as less warm but as somewhat competent

are likely to experience envy from others, and envy generates dislike and hostility.

Groups are perceived as being relatively low in both competence and warmth tend to

be accorded lower social status and more likely to be viewed with contempt.

Figure 4.3 Evaluations of each protected characteristic group on warmth and

competence

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Towards a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

34

4.7 Social distance

‘How comfortable or uncomfortable do you think you would feel if a

suitably qualified person was appointed as your boss if they

were…’ [protected characteristics included are: a person with a

mental health condition, a black person, a Muslim, a pregnant

woman or new mother, a woman, a gay, lesbian or bisexual person,

a disabled person with physical impairment, a person over 70]

‘How comfortable or uncomfortable do you think you would feel if

someone married one of your close relatives (such as a brother,

sister, child or re-married parent if they were…’ [protected

characteristics included are: a person who represent their gender

differently, an immigrant, a gay, lesbian or bisexual person, a

Muslim]

‘How comfortable or uncomfortable do you think you would feel if

someone moved in next door to you if they were…’ [protected

characteristics included are: a black person, a person with a mental

health condition, an immigrant, a disabled person]

1 ‘very comfortable’ to 5 ‘not very comfortable’

‘don't know’ and ‘prefer not to say’.

someone married one of your close relatives (such as a brother,

sister, child or re-married parent if they were…’ [protected

characteristics included are: a person who represent their gender

differently, an immigrant, a gay, lesbian or bisexual person, a Muslim]

The responses to these questions can be assessed in various ways (for example, on

how many of the items people say they would be uncomfortable with, or their

average level of discomfort, etc.). As with the thermometer data it is also useful to

compare social distance responses toward different protected characteristics. Figure

4.4 and figure 4.5 show, for example, that there is quite strong discomfort with the

idea of connection to a person with a mental health condition, not only as a boss

(25%), but also as a family member (29%). However, we did not apply all questions

to all protected characteristics in this survey, both for practical and survey-length

considerations.

Figure 4.4 How comfortable would you feel if a member of the relevant group

was appointed as your boss?

‘How comfortable or uncomfortable do you think you would feel if

someone moved in next door to you if they were…’ [protected

characteristics included are: a black person, a person with a mental

health condition, an immigrant, a disabled person]

1 ‘very comfortable’ to 5 ‘not very comfortable’

‘don't know’ and ‘prefer not to say’.

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Towards a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

35

Base – all GB respondents excluding target group: person with a mental health condition

933; a black person 1,027; a Muslim 1,031; a pregnant woman or new mother 1,123; a

woman 482; a gay lesbian or bisexual person 1,057; a disabled person with a physical

impairment 834; person aged over 70 900.

77

73

71

67

61

58

48

35

19

21

22

23

34

33

37

40

4

6

8

9

5

9

15

25

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

A woman A pregnant

woman or

new mother

A disabled

person with

a physical

impairment

A gay,

lesbian or

bisexual

person

A black

person

Person aged

over 70

A Muslim A person

with a

mental

health

condition

%

Net: Comfortable Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable Net: Uncomfortable

Figure 4.5 How comfortable would you feel if a member of the relevant

protected characteristic moved in next door to you?

Base – all GB adults aged 18+ excluding the target group: a person who presents their

gender differently to the one they were assigned at birth 1,051; an immigrant 1,126; a gay,

lesbian or bisexual person 1,058; a Muslim 1,033.

52

48

63

45

34

33

29

37

14

19

8

18

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

A person who presents

their gender differently

to the one they were

assigned at birth

An immigrant A gay, lesbian or

bisexual person

A Muslim

%

Net: Comfortable Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable Net: Uncomfortable

Equality and Human Rights Commission

Published: October 2018

Towards a national barometer of prejudice and discrimination in Britain

36

Figure 4.6 shows that around one fifth of respondents said they would feel

uncomfortable if either an immigrant or a Muslim person moved in next door.

Figure 4.6 How comfortable would you feel if a person with one of the relevant

protected characteristics married one of your close relatives?

59

35

50

63

32

36

30

29

9

29

20

8

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

A black person A person with a mental

health condition

An immigrant A disabled person with

a physical impairment

%

Net: Comfortable Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable Net: Uncomfortable

Base – all GB adults aged 18+ excluding the target group: a black person 1,032; a person

with a mental health condition 938; an immigrant 1,124; a disabled person with a physical

impairment 835.

Figure 4.6 and figure 4.8 also show that attitudes in relation to disability differs

markedly depending on whether we ask about physical and mental conditions. It is

worth recalling that the feeling thermometer revealed similarly (very) low numbers of