Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 59

Using an English self-assessment tool to validate an

English Placement Test

Zhi Li

12

Iowa State University

This study aimed to develop and use a contextualized self-

assessment of English proficiency as a tool to validate an English

Placement Test (MEPT) at a large Midwestern university in the

U.S. More specifically, the self-assessment tool was expected to

provide evidence for the extrapolation inference within an

argument-based validity framework. 217 English as a second

language (ESL) students participated in this study in the 2014

spring semester and 181 of them provided valid responses to the

self-assessment. The results of a Rasch model-based item analysis

indicated that the self-assessment items exhibited acceptable

reliabilities and good item discrimination. There were no misfitting

items in the self-assessment and the Likert scale used in the self-

assessment functioned well. The results from confirmatory factor

analysis indicated that a hypothesized correlated four-factor model

fitted the self-assessment data. However, the multitrait-

multimethod analyses revealed weak to moderate correlation

coefficients between participants’ self-assessment and their

performances on both the MEPT and the TOEFL iBT. Possible

factors contributing to this relationship were discussed.

Nonetheless, given the acceptable psychometric quality and a clear

factor structure of the self-assessment, this could be a promising

tool in providing evidence for the extrapolation inference of the

placement test score interpretation and use.

Key words: English Placement Test, Self-assessment, Argument-

based validation, Extrapolation inference, Multitrait-multimethod

analysis

1

Zhi Li, Department of English, Iowa State University, 206 Ross Hall, Ames, IA. 50010 USA. E-mail: zhili@iastate.edu

60 Z. Li

Introduction

English placement tests (EPTs) are commonly used as a post-entry language

assessment (PELA) to supplement the use of standardized English proficiency tests

and, more importantly, to address local needs of ESL teaching through re-assessing

and placing ESL students into appropriate ESL classes (Fulcher, 1996). Considering

its impact on students’ English learning as well as the influence of English

proficiency on students’ academic achievement (Graham, 1987; Light, Xu, &

Mossop, 1987; Phakiti, Hirsh, & Woodrow, 2013; Vinke & Jochems, 1992), efforts to

validate the interpretation and use of EPTs scores are needed (Knoch & Elder,

2013).

Research background

An argument-based approach to validation

EPTs can play an important role in facilitating English teaching and learning

through grouping ESL students who share similar needs in English learning into

the same classes. To make a statement about the positive effects of EPTs on both

ESL education and students’ development, we need to validate the interpretation

and use of the scores from these tests. Typically, the scores from an EPT are

claimed, explicitly or implicitly, to be indicative of students’ English proficiency

levels in an academic context and thus can be used to make decisions on academic

ESL course placement. The placement decisions based on the EPT scores also

reflect an underlying belief that adequate English proficiency is necessary for ESL

learners to achieve academic success. However, the intended score interpretation

and impact of the placement decisions of EPTs in general are still a largely under-

researched area (Green & Weir, 2004).

According to Kane (2013), an argument-based approach to validation focuses on

the plausibility of the claims that are made based on the test scores, which entail a

series of inferences from the test responses to test score interpretation and use. In

this sense, validation efforts should be directed to constructing specific arguments

with regard to particular inferences. To this end, an interpretation and use

argument (IUA) for an EPT is needed. Following the structure of the interpretive

argument for the TOEFL iBT proposed by Chapelle, Enright, and Jamieson (2008),

an interpretation and use argument (IUA) for an English Placement Test used at a

large Midwestern university in the U.S. (herein referred to as the MEPT) is

presented to specify the proposed claims about test score interpretation and use.

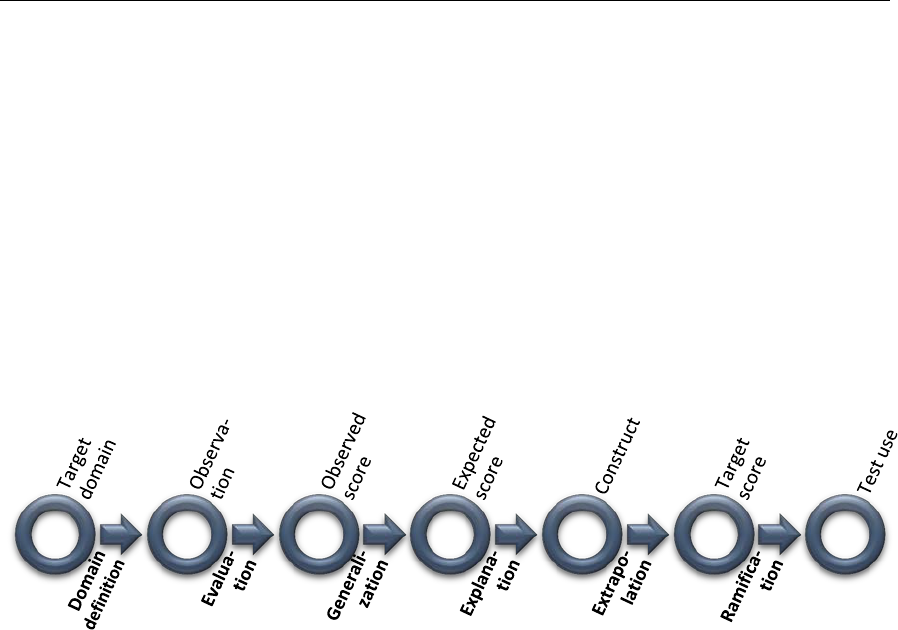

As shown in Figure1, the circle represents a source of data for analysis and an

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 61

outcome data as a result of an adjacent inference, while the arrow embodies an

inference linking two data sources and the label of the inference is shown

underneath the arrow. This series of inferences reflects the process of target

domain identification (Domain definition inference), item scoring (Evaluation

inference), reliability estimation (Generalization inference), theoretical explanation

of scores (Explanation inference), matching scores with actual performance in the

target domain (Extrapolation inference), and establishing the impact of decisions

based on the scores (Ramification inference).

Figure 1. An interpretation and use argument for the MEPT

The interpretation and use argument for the MEPT can help lay out a research plan

and guide the choice of research methods for each inference. This study focused

specifically on the extrapolation inference of the MEPT for two reasons. Firstly, one

of the important sources of validity evidence is from the test-takers’ perspectives

and the extrapolation inference addresses the relationship between test scores and

test-takers’ actual performance in a targeted domain. However, the test-takers’

voice is rarely heard and their real-life performances in educational contexts are

seldom associated with test performances in the literature of EPTs (Bradshaw,

1990). Secondly, in addition to the documentation of the test development and

regular item analysis, there are several validation studies conducted for the MEPT,

but very limited efforts have been devoted to the extrapolation inference. For

example, Le (2010) proposed an interpretive argument for the listening section of

the MEPT and conducted an empirical study on four main inferences, namely,

domain analysis, evaluation, generalization, and explanation. Yang and Li (2013)

examined the explanation inference of the MEPT through an investigation of the

factor structure and the factorial invariance of the MEPT. They found that the

identified factor structure of the listening and reading sections of the MEPT

matched the structure of the constructs described in the test specifications and

factorial invariance of the constructs was further confirmed in a multi-group

62 Z. Li

confirmatory factor analysis. Manganello (2011) conducted a correlational study

comparing the MEPT with the TOEFL iBT and found that the TOEFL iBT scores

had a moderate correlation with the test administered from fall 2009 to spring

2011. However, further evidence was needed regarding the interpretation and use

of the test scores to support the extrapolation inference.

Extrapolation inference and self-assessment

In the interpretation and use argument for the MEPT, the extrapolation inference

links the construct of language proficiency as represented by the scores or levels of

sub-skills (reading, listening, and writing skills) to the target scores, which are the

quality of performance in the real-world domain of interest. The diagram in Figure

2 presents the extrapolation inference with its grounds, claims, and supporting

statement in Toulmin’s notation for argument, in which the claim is established

with a support of the warrants and/or a lack of support of the rebuttals. As shown

in Figure 2, the claim warranted by the extrapolation inference is that the scores on

the MEPT or the expected scores of the MEPT reflect learners’ actual English

proficiency in academic contexts at that university (the target scores). The

assumptions underlying this inference include that the constructs of academic

language proficiency as assessed by the EPT account for the quality of linguistic

performance at that university. Typical backing for the assumptions includes

findings in criterion-related validation studies, in which an external criterion that

represents test-taker’s performance in targeted domain is employed (Riazi, 2013).

Therefore, a key step in establishing the extrapolation inference is to identify an

appropriate external criterion and use it as a reference to compare test-takers’

MEPT performance.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 63

Figure 2. Extrapolation inference for the MEPT

Possible external criteria are concurrent measures of English proficiency, such as

standardized English proficiency tests, student self-assessment, and teacher

evaluation. A typical practice of this type of criterion-related validity is to correlate

the scores on the target test with those on a well-established test, such as TOEFL

and IELTS, assuming that both the target test and the reference test measure a set

of similar, if not the same, constructs. Several studies investigated the relationship

between the standardized English proficiency tests and local EPTs and reported

moderate correlation coefficients. For example, In Manganello (2011), the

correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r) for the reading section between the MEPT and

the TOEFL iBT was .363 and the correlation coefficient for the listening section was

.413. The correlation coefficient (Spearman’s rho) for the writing section between

the two tests was .317. Kokhan (2012) studied the possibility of using TOEFL scores

for university ESL course placement decisions at the University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign. She found that the correlation coefficients between the TOEFL

scores and the scores on the local EPT varied when the lag between the TOEFL test

64 Z. Li

and the EPT was taken into consideration. Overall, the highest correlation

coefficient was below .400 in the case where TOEFL was taken most recently by the

students. However, with a wider interval gap between the TOEFL and the EPT in

time, the correlation coefficients became even smaller. Considering the potential

impact of misplacement using the TOEFL scores, Kokhan (2013) made an explicit

argument against using standardized test results from SAT, ACT, and the TOEFL

iBT for placement purposes at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Kokhan’s argument is echoed in Fox (2009), a study on the impacts of using TOEFL

and IELTS scores for placement purposes at a Canadian university. Fox reported a

number of misplacement cases resulted from using the standardized tests in that

institute. In view of the existing studies on the relationship between standardized

English proficiency tests and local EPTs, it was hypothesized that a significant but

relatively weak to moderate correlation exists between the standardized English

proficiency tests (TOEFL and IELTS) and the MEPT.

Like standardized tests, self-assessment can be a possible tool to support the

extrapolation inference of the MEPT in a criterion-related validation study.

Previous studies have showed that self-assessment can be a reliable learner-

directed measure of English proficiency that brings test-takers’ voices to the

validation process (LeBlanc & Painchaud, 1985; Ross, 1998). Self-assessment has

also been used as a supplementary tool to existing assessment projects, as the ones

used in DIALANG and the European Language Portfolio (ELP) project (Alderson,

2005; Engelhardt & Pfingsthorn, 2013; Hellekjær, 2009; Lee & Greene, 2007).

Furthermore, self-assessment may be one of the most accessible instruments that

can easily reach out to most of the targeting participants with a uniform set of

items, compared with teacher evaluation.

The utility of self-assessment of English skills has been explored mainly via

correlational analyses with other measures, for example, scores on standardized

tests and teacher ratings. Overall, the findings about the correlation of self-

assessment are promising, although the magnitude of correlation coefficients

varies from study to study depending on the item format and specificity of item

content (Brantmeier, 2006; LeBlanc & Painchaud, 1985; Luoma, 2013; Oscarson,

2013; Ross, 1998). Self-assessment also has its value as an alternative to some

exiting tests or as a tool to validate a test. For example, LeBlanc and Painchaud

(1985) used a planned self-assessment questionnaire as a placement tool which

contained 60 ‘can-do’ statements with reference to specific situations. They found

that the self-assessment tool produced high quality results and placed students in a

similar way as the standardized tests. Malabonga, Kenyon, and Carpenter (2006)

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 65

investigated the relationship between university students’ performances on a self-

assessment and a computerized oral proficiency test of foreign language. It was

found that 98% of the students in that study could successfully use the self-

assessment to select the test tasks that were appropriate to their foreign language

proficiency levels. Furthermore, the correlation between the self-assessment and

teacher ratings of oral proficiency ranged from .74 to .81.

In a validation study of the TOEFL iBT, a self-assessment, along with academic

placement and instructor’s ratings, was used as a piece of evidence for the

extrapolation inference (Enright, Bridgeman, Eignor, Lee, & Powers, 2008). Using

confirmatory factor analysis, Enright et al. (2008) identified four factors

corresponding to the four sub-skills (reading, listening, speaking, and writing) in

the self-assessment. The four factors in the self-assessment were found to have a

moderate and positive correlation with test-taker’s performance on both TOEFL

PBT and the prototype measures of the TOEFL iBT, with the correlation

coefficients ranging from .30 to .62. Enright et al. (2008) regarded the magnitude of

correlation to be ‘high’ and ‘similar in magnitude to other test-criterion

relationships’ (p. 178).

Based on the studies discussed above, self-assessment has the potential to be used

as one of the external criteria in language testing research. The main goal of the

study was to develop a contextualized self-assessment of English use as a tool to

validate the MEPT. Accordingly, three research questions were raised in this study

pertaining to the self-assessment and the MEPT.

1) How did the self-assessment items function in terms of reliability, item difficulty

and discrimination?

2) To what extent did the factor structure of self-assessment items reflect the

intended constructs?

3) To what extent were students’ MEPT performances related to their self-

assessment of English use and their TOEFL iBT scores?

The first two research questions focused on the quality of the self-assessment tool

and the third research question addressed the extrapolation inference of the MEPT

as shown by the relationship among the three English measures (self-assessment,

the MEPT, and the TOEFL iBT).

66 Z. Li

Methodology

Participants

The participants in this study were the newly admitted ESL students at a large

Midwestern university in the U.S. A total of 217 ESL students participated in this

study; 213 were enrolled in the ESL courses based on their performance on the

MEPT and the remaining four participants either passed the MEPT or were waived

from taking the ESL courses. Unfortunately, this study did not include the students

with a high TOEFL iBT or IELTS score, who were exempted from the MEPT. To

ensure a good quality of the self-assessment data, I manually screened the data to

identify the participants who spent little time on the self-assessment or showed

disingenuous response patterns in the self-assessment. This screening process cut

down the sample size from 217 to 181, but yielded a better quality data set for

analysis. This sample size is adequate for Rasch model analysis and acceptable

confirmatory factor analysis with a participant to item ratio of 8:1 (Worthington &

Whittaker, 2006).

Of the remaining 181 participants, 73 were females, 105 were males, and three

participants did not specify their gender. First languages of the participants

included Chinese (101), Korean (29), Malay (8), Hindi (8), Arabic (7), Indonesian

(1), Turkish (1), Vietnamese (1), Spanish (1), Thai (1), and other unspecified

languages. 123 of the participants were undergraduate students and 58 were

graduate students. 91 participants took the MEPT at the beginning of the spring

semester in 2014. 83 participants took the MEPT in 2013 but were enrolled in some

ESL courses in the 2014 spring semester, which means they have been studying in

the U.S. for at least one semester. Three participants took the EPT in 2012 and four

participants did not provide this information.

Instruments

The English Placement Test

The MEPT is a post-entry English test for new international students whose native

language is not English. There are three sections in the MEPT, namely, reading

comprehension, listening comprehension, and essay writing. Correspondingly, the

MEPT scores represent three skills of ESL learners’ academic English proficiency,

i.e., reading, listening, and writing skills. The scores are used as indicators of

whether the students need further ESL assistance and as a criterion for the

decisions of ESL course placement.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 67

The self-assessment of English use

The contextualized self-assessment was developed as a part of a comprehensive

online survey, which consisted of 54 statements on a six-point Likert scale in five

sections: Self-assessment of English use (21 items), Academic self-efficacy (5 items),

Learning motivation (8 items), Self-regulated learning strategies (10 items), and

Anxiety about using English (10 items) (see Appendix for the self-assessment

items). All the items had been piloted with a small number of students from the

target population and reviewed by experts in Applied Linguistics. In this study, I

focused on the quality of the self-assessment items only.

The self-assessment items were developed based on the literature of self-

assessment research and informal interviews with ESL students for their typical

English use at the university. The self-assessment descriptors in European

Language Portfolio (ELP) (B1-C1) and descriptors in ACTFL (Intermediate high to

Advanced-low) were reviewed and some descriptors were modified to

accommodate the language use scenarios in university context. The self-assessment

items were written as ‘can-do’ statements about the four skills (i.e., listening,

reading, speaking, and writing) with reference to students’ activities in content

courses or major courses.

Procedures

To reach a satisfying response rate to the self-assessment, I visited the ESL classes

to recruit participants and I sent an invitation email to the ESL students who

passed the EPT or were waived from taking the ESL courses in weeks six and

seven in the spring semester in 2014. The timing of the self-assessment

administration was decided with a consideration that students could better self-

assess English proficiency in academic contexts when they were familiar with the

English language requirements in their content courses. The self-assessment was

administered and distributed via Qualtrics, a web-based survey service. An

electronic informed consent form was presented on the first page of the online

survey and voluntary participation was stressed in the informed consent form.

The test performance data, including participants’ TOEFL iBT or IELTS scores and

their MEPT scores were obtained from the Registrar’s office and the EPT office

with an approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the university. All

the test performance data were de-identified for analysis after being matched to

participants’ self-assessment responses.

68 Z. Li

Data analysis

In the study, I took a quantitative approach to investigating the quality of the self-

assessment tool and exploring its relationship with the MEPT and the TOEFL iBT.

SPSS 21 (IBM Corp. 2012), Amos 21, and Winsteps 3.64.0 (Linacre, 2011) were used

for quantitative data analysis.

To examine the quality of the self-assessment items, a Rash model-based item

analysis was conducted to investigate the item reliability, person reliability, item

difficulty, item discrimination, and scale functioning using Winsteps. The

assumption of unidimensionality was checked with both exploratory factor

analysis (maximum likelihood extraction and promax rotation) and Rasch

principal component analysis of residuals. Since the self-assessment items were

constructed based on the same six-point Likert scale, Andrich’s rating scale model

was considered as an appropriate model for the polytomous responses in this

study (Bond & Fox, 2007).

To examine the factor structure of the self-assessment items, I followed the

procedures and suggestions for scale development and validation proposed by

Worthington and Whittaker (2006). The factor structure was investigated using

confirmatory factor analysis with three theoretically plausible models of English

proficiency proposed and tested. Considering the typical non-normal distribution

associated with Likert-scale based items (Leung, 2011), bootstrapping was used in

the confirmatory factor analysis to address the issue of non-normality.

Bootstrapping is a re-sampling technique that treats the sample as a population

from which multiple sub-samples are randomly drawn with replacement. In

confirmatory factor analysis, the random samples generated with bootstrapping

are analyzed separately and the results are averaged across these samples (Brown,

2006).

Multiple model fit indices were employed to help decide which model fitted best.

Chi-square (χ

2

) was reported as the classic goodness-of-fit index in this study. A

non-significant chi-square (p > .05) indicates that we should fail to reject the null

hypothesis that the proposed model generates the same variances and covariances

as those in the sample data. However, chi-square is sensitive to sample size. In this

study, I also reported the ratio of chi-square to degree of freedom (χ

2

/df) with a

value less than 2.0 being regarded as good model fit (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). In

addition, comparative fit index (CFI) as a type of relative fit indices compares the

chi-square value to a baseline model. A CFI of .90 or .95 is indicative of good model

fit (Bryne, 2010). Lastly, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 69

used as an absolute model fit index, which penalizes poor model parsimony and is

usually accompanied with a 90% confidence interval to gauge the index precision

(Brown, 2006). A RMSEA value less than 0.05 indicates a good model fit and 0.08

indicates an acceptable model fit. The final factor structure was determined based

on the model fit indices and theoretical soundness.

Once the factor structure of the self-assessment was determined, factor scores of

the identified constructs in the self-assessment were calculated for each participant

and used in the subsequent correlational analyses. A multitrait-multimethod

(MTMM) matrix was constructed with the correlation coefficients between the

three measures (i.e., self-assessment, the MEPT, and the TOEFL iBT) of four traits

or subskills (i.e., reading, listening, speaking, and writing). The IELTS scores were

excluded from this MTMM matrix due to a small number of participants who

reported IELTS scores. The MTMM matrix consisted of Pearson’s r and Spearman’s

rho. The latter was for the correlation coefficients involving the MEPT writing

grade, which is on a three-point ordinal scale. Evidence about convergent validity,

discriminant validity, and test methods was collected from an analysis of the

MTMM matrix. Due to a lack of reliability information for some sections of the

measures, the correlation coefficients discussed in this paper are the raw

coefficients without correction for attenuation, unless otherwise specified.

Results and Discussions

The quality of the self-assessment

To evaluate the quality of the self-assessment tool, a Rasch measurement analysis

using the rating scale model was conducted for each of the subscales. The decision

of running separate Rasch analyses for each subscale was made based on the result

of an exploratory factor analysis. This decision was confirmed with the results of

Rasch principal component analysis of residuals (see Table 1). The proportion of

variance explained by the first dimension is substantial (from 71.1% to 78.1%) and

the eigenvalue for the first contrast is less than 2.0 in all four subscales (Linacre,

2011).

Table 1 also shows the reliability information of the four subscales. The person

reliability, an equivalent of Cronbach’s alpha in the Rasch measurement analysis,

ranged from 0.86 to 0.89 and the person separation index ranged from 2.46 to 2.89.

The item reliability in the Rasch measurement analysis refers to the replicability of

the item ordering if the items are administered to a group of subjects with similar

abilities. The item reliability of the subscales ranged from 0.88 to 0.98 and the item

70 Z. Li

separation index ranged from 2.69 to 7.72. Overall, the four subscales of the self-

assessment tool exhibited acceptable reliability.

Table 1. Results of Rasch measurement analysis: reliability and unidimensionality check (N = 181)

Self-assessment

Subscale

Person

Separation

Person

reliability

Item

Separation

Item

reliability

Variance

explained

Eigenvalue for

1st contrast

Reading (k=5)

2.46 .86 7.72 .98 74.4% 1.9

Listening (k=5)

2.75 .88 4.54 .95 78.1% 1.6

Speaking (k=5)

2.89 .89 2.69 .88 74.0% 1.7

Writing (k=6)

2.78 .89 2.81 .89 71.7% 1.5

To examine the item quality, descriptive statistics, Rasch item measures, and

item-level fit statistics were reported for each subscale in Table 2. The descriptive

statistics reveal that the means of the responses were relatively high, ranging from

3.98 to 5.18. The standard deviations were also large, ranging from 0.94 to 1.27.

This suggests that the participants in general evaluated their English subskills in a

positive way and there was some variability in their responses. Some self-

assessment items had high skewness and/or kurtosis, thus calling for a careful look

at the data distribution.

The item measure or endorsability of the self-assessment statement is estimated on

the common scale with logit as the measurement unit. Overall, the self-assessment

items showed a relatively narrow range in item measure (-1.82 to 1.70). In a rating

scale model, an estimation of the threshold value of the Likert scale is more

meaningful as it tests the functionality of the scale, which will be discussed later.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 71

Table 2. Results of Rasch measurement analysis: item measure and fit statistics

SA

Section

Items Item

measure

(logit)

S.E. Infit

MNSQ

Outfit

MNSQ

Point-

biserial

coefficient

M SD Skew-

ness

Kur-

tosis

Reading

Rd1 -1.82 0.16 1.13 1.07 .79 5.18 0.97 -1.83 4.46

Rd2 -0.21 0.14 1.03 1.02 .82 4.79 0.97 -0.89 1.19

Rd3 -0.38 0.15 0.68 0.65 .87 4.83 0.98 -1.13 2.14

Rd4 1.70 0.13 1.34 1.34 .79 4.23 1.10 -0.35 -0.03

Rd5 0.71 0.14 0.85 0.89 .85 4.54 0.94 -0.57 0.80

Listening

Lsn1 -1.02 0.13 0.77 0.77 .84 4.67 1.07 -1.20 1.67

Lsn2 0.76 0.12 1.00 1.04 .85 4.04 1.27 -0.31 -0.51

Lsn3 -0.02 0.12 0.84 0.81 .86 4.34 1.08 -0.44 0.14

Lsn4 0.37 0.12 1.27 1.32 .81 4.19 1.23 -0.94 -0.56

Lsn5 -0.09 0.12 0.99 0.96 .83 4.36 1.09 -0.57 0.25

Speaking

Spk1 -0.67 0.14 0.81 0.79 .90 4.32 1.14 -0.44 -0.28

Spk2 0.08 0.14 0.87 0.87 .86 4.08 1.05 0.63 0.29

Spk3 0.47 0.14 0.97 0.99 .85 3.98 1.09 -0.30 -0.16

Spk4 0.32 0.14 1.05 1.03 .84 4.02 1.07 -0.37 -0.27

Spk5 -0.20 0.14 1.26 1.25 .84 4.18 1.14 -0.29 -0.30

Writing

Wrt1 -0.04 0.13 1.05 1.02 .81 4.30 1.01 -0.27 -0.26

Wrt2 -0.30 0.13 1.07 1.00 .81 4.38 1.03 -0.48 0.14

Wrt3 -0.16 0.13 0.80 0.83 .83 4.33 0.99 -0.62 0.76

Wrt4 0.85 0.13 1.10 1.13 .80 3.99 1.05 -0.28 -0.20

Wrt5 -0.01 0.13 0.81 0.83 .84 4.29 0.99 -0.36 0.06

Wrt6 -0.35 0.13 1.12 1.08 .77 4.40 0.98 -0.49 0.10

72 Z. Li

According to Bond and Fox (2007), the infit and outfit mean squares (MNSQ) as

unstandardized fit statistics are used to assess whether an item functions as the

Rasch model expects. Infit is a weighted fit statistic and is less sensitive to outliers,

compared with outfit, an unweighted fit statistic. The expected mean square value

of the infit and outfit statistics is 1.0. The value range from 0.5 to 1.5 is generally

regarded as an acceptable fit to the Rasch model (Green, 2013). As shown in Table

2, all the mean square values of the infit and outfit statistics were within the range

of 0.5 to 1.5, indicating that the self-assessment items were functioning as the Rasch

model predicted. Another relevant item quality index is the point-biserial

correlation coefficient of each item, which is the discrimination index in the

classical test theory (CTT) framework. All the self-assessment items had relatively

high point-biserial correlation coefficients (.77 to .90), which indicates that the self-

assessment items had a good discrimination among the participants.

Similar to the consideration of item fit in Rasch analysis, the categories of

the Likert scale should also exhibit a good model fit. According to Bond and Fox

(2007), the following four characteristics of a rating scale should be checked: the

count frequency, monotonicity of category average measures, threshold or step

calibrations, and category fit. It is recommended that the count for each category

should be no less than 10, the distance between thresholds should be at least 1.4

logits but less than 5 logits, and the infit statistics for each category should be

acceptable. Tables 3 to 6 contain the category functioning information for each

subscale of the self-assessment items.

Table 3 shows that the responses to the reading self-assessment items were highly

skewed with only 11% of the responses falling into the first three categories,

namely ‘Strongly disagree’, ‘Disagree’, and ‘Somewhat disagree’. There were only

three responses in the category of ‘Strongly disagree’. This low frequency suggests

that this category may be redundant. The skewness in the reading subscale may

reflect that the ESL students in general have a relatively high proficiency in

academic reading. Since low category counts may lead to a less reliable estimate of

the threshold value (Bond & Fox, 2007), it is advisable to collapse the adjacent

categories to revise the scale for a correct interpretation of the scale.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 73

Table 3. Results of Rasch measurement analysis: Rating scale category statistics for the reading

section

Cate-

gory

Reading with original scale Reading with revised scale

Count

(%)

Obs.

average

Infit

/Outfit

MNSQ

Structure

calibration

Count

(%)

Obs.

average

Infit/

Outfit

MNSQ

Structure

calibration

1

3 (0%) -3.75 2.60/1.66 None

2

25 (3%) -2.60 1.27/1.23 -6.41 18 (2%) -3.13 1.41/1.38 None

3

65 (8%) 0.09 1.12/1.17 -2.09 65 (8%) -1.51 1.12/1.24 -3.77

4

232 (28%) 1.93 0.92/0.90 -0.21 232 (28%) 0.33 0.92/0.90 -1.82

5

366 (44%) 4.02 1.03/0.98 2.53 366 (44%) 2.45 1.04/0.99 0.94

6

139 (17%) 6.52 0.89/0.88 6.19 139 (17%) 4.99 0.90/0.88 4.46

The statistics related with the revised scale are listed on the right side of Table 3.

The observed average ability of the participants increased monotonically in the

revised scale, from -3.13 to 4.99. This indicates that the participants with higher

ability tended to endorse or choose a higher category. Both infit and outfit mean

squares of each category were within the acceptable range (from 0.5 to 1.5). The

distances between thresholds were greater than 1.4 logits but less than 5 logits.

This clear monotonic change pattern in threshold value can be observed in the

category probability curves for the Reading (SA_R1), Listening (SA_L1), Speaking

(SA_S1) and Writing (SA_W1) subscales respectively (Figure 3). Overall, the Likert

scale for the reading items functioned well.

74 Z. Li

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 75

Figure 3. Category probability curves for the subscales of self-assessment.

The Likert scale for the listening items also exhibited good qualities, as shown in

Table 4. The responses to the listening self-assessment items were less skewed

compared with those to the reading items. The response counts met the minimum

requirement (10) for a functioning scale. As expected, the observed average ability

of the participants increased monotonically along the Likert scale. Both infit and

outfit mean squares of each category were within the acceptable range from 0.5 to

1.5. The distances between thresholds were greater than 1.4 logits but less than 5

logits. This clear monotonic change pattern in threshold can be observed in the

category probability curve in Figure 3.

76 Z. Li

Table 4. Results of Rasch measurement analysis: Rating scale category statistics for the listening

section

Category Listening with original scale

Count (%) Obs. average Infit /Outfit MNSQ Structure

calibration

1

16 (2%) -4.09 1.16/1.12 None

2

54 (6%) -2.41 0.92/0.99 -4.44

3

125 (14%) -0.47 0.89/0.88 -2.19

4

273 (31%) 1.12 0.98/0.98 -0.44

5

302 (35%) 2.90 1.00/0.99 1.84

6

100 (11%) 5.38 1.09/1.05 5.23

The Likert scale for the speaking and writing items functioned well as shown in

Tables 5 and 6. However, the responses to the speaking and writing self-

assessment items were slightly skewed with a majority of the responses falling into

the last three categories, namely ‘Somewhat Agree’, ‘Agree’, and ‘Strongly agree’.

Similar to the response pattern in the reading items, there were low count

frequencies in the category of ‘Strongly disagree’. Therefore, the first two

categories were collapsed into one category for a reasonable interpretation of the

Likert scale.

The statistics related with the revised scale are listed on the right side of Tables 5

and 6. As shown below, the observed average ability of the participants increased

monotonically in the revised scale. Both infit and outfit mean squares were within

the acceptable range from 0.5 to 1.5. The distances between thresholds were greater

than 1.4 logits but less than 5 logits. The monotonic change patterns in threshold

can be observed in the category probability curve in Figure 3.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 77

Table 5. Results of Rasch measurement analysis: Rating scale category statistics for the speaking

section

Cate-

gory

Speaking with original scale Speaking with revised scale

Count

(%)

Obs.

average

Infit

/Outfit

MNSQ

Structure

calibration

Count

(%)

Obs.

average

Infit/

Outfit

MNSQ

Structure

calibration

1 7 (1%) -7.15 0.94/1.01 None

2 60 (7%) -2.63 1.15/1.15 -7.23 52 (6%) -3.82 1.14/1.14 None

3 174 (20%) -0.53 1.01/1.02 -2.58 174 (20%) -2.32 1.01/1.03 -4.36

4 304 (34%) 1.69 0.94/0.94 0.02 304 (34%) -0.12 0.93/0.93 -1.78

5 276 (31%) 4.16 1.02/0.99 3.01 276 (31%) 2.34 1.01/0.99 1.20

6 69 (8%) 6.63 0.93/0.90 6.78 69 (8%) 4.79 0.92/0.90 4.94

Table 6. Results of Rasch measurement analysis: Rating scale category statistics for the writing

section

Cate-

gory

Writing with original scale Writing with revised scale

Count

(%)

Obs.

average

Infit

/Outfit

MNSQ

Structure

calibration

Count

(%)

Obs.

average

Infit/

Outfit

MNSQ

Structure

calibration

1 7 (1%) -5.01 1.00/0.97 None

2 45 (4%) -1.77 1.09/1.10 -5.16 52 (5%) -3.42 1.14/1.16 None

3 168 (16%) -0.57 0.88/0.87 -2.48 168 (16%) -1.87 0.84/0.86 -3.77

4 386 (36%) 1.14 0.93/0.92 -0.52 386 (36%) -0.15 0.95/0.94 -1.81

5 374 (35%) 3.39 0.95/0.95 2.21 374 (35%) 2.11 0.94/0.94 0.92

6 88 (8%) 5.51 1.31/1.17 5.95 88 (8%) 4.22 1.31/1.17 4.65

78 Z. Li

Overall, the Rasch analysis results indicate that the self-assessment items have a

good quality in terms of reliability, item discrimination, item fit statistics, and scale

functioning.

The factor structure of the self-assessment tool.

In order to examine the factor structure of the self-assessment tool, confirmatory

factor analysis was used to assess how well the data fit three theoretically plausible

models, namely correlated four-factor model, unitary factor model, and secondary

factor model (see Figure 5). These three models were proposed based on different

views of the constructs of English proficiency (Sawaki, Stricker, & Oranje, 2009;

Song, 2008). In Figure 5, the circles represent the latent variables measured in the

self-assessment and the rectangular boxes represent the specific self-assessment

items as observed variables.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 79

Figure 5. Proposed models of English proficiency as measured by the self-assessment.

The specified models were identified using the t-rule and correlated errors rule.

The t-rule is a necessary but not sufficient condition for model identification and it

states that the number of freely estimated parameters should be less than or equal

to the number of known parameters for model identification (Bollen, 1989). The

correlated errors rule is a sufficient but not necessary condition of identification. It

is an expansion of two-indicator rule and three-indicator rule and allows for

limited correlation among the measurement errors.

The assumption of both univariate and multivariate normality of the sample data

was checked. It is found that the data did not follow a normal distribution. The

80 Z. Li

critical ratio for univariate skewness ranges from -9.949 to -1.464 and the critical

ratio for the univariate kurtosis ranges from 0.186 to 11.831. The multivariate

kurtosis is 79.550 with a critical ratio 17.224. The Mahalanobis distance was

checked for potential multivariate outliers. Considering the non-normality of the

data, bootstrapping was used (2000 bootstrap samples) to determine parameter

estimates and the Bollen-Stine corrected p value of the chi-square was reported

(Byrne, 2010).

The model fit indices for the three proposed models are listed in Table 7. The chi-

square values for the three models were statistically significant (p < .001) and the

Bollen-Stine p values for chi-square were also statistically significant, which

suggests a rejection of the null hypothesis that the variances and covariance

generated by the models are the same as the ones in the sample. However, the

other model fit indices, including χ

2

/df, CFI, and RMSEA, all indicated an

acceptable to good model fit of the three models. The values of CFI were over .90

and the values of the RMSEA were less than .08, while only the χ

2

/df of unitary

factor model was over 2.0.

By comparison, the correlated four-factor model showed the best model fit with

smallest χ

2

/df (1.767), highest CFI (.956), and lowest RMSEA (.065). In addition, the

chi-square difference tests between the correlated four-factor model and two other

models suggest that the correlated four factor model fitted the data better (∆χ

2

(7)M1-

M2

= 40.02, p < .001 and ∆χ

2

(2) M1-M3 = - 32.71, p < .001).

Table 7. Model fit indices of the competing models for the self-assessment

Model χ

2

(df) p value χ

2

/df CFI RMSEA

90% C.I.

Bollen-Stine

bootstrap p-value

M1 Correlated

4-factor model

310.94

(176)

.000 1.767 .956 .065

(.053, .077)

.015

M2 Unitary

factor model

350.96

(169)

.000 2.077 .940 .077

(.066, .089)

.005

M3 Secondary

factor model

343.65

(178)

.000 1.931 .946 .072

(.060, .083)

.004

Note: CFI = comparative fit index, RMSEA = the root mean square error of approximation.

Nearly all of the standardized factor loadings in the correlated four-factor model

were over .7, except for two reading items (.670 and .684). The four subskills

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 81

represented as four latent constructs showed high correlation coefficients among

them. The highest correlation is between speaking and writing (.89), followed by

the correlation between listening and speaking (.85) and between reading and

listening (.84). Reading had a relatively lower correlation with speaking (.68) and

writing (.77).

The results from confirmatory factor analysis indicate that the self-assessment

covered four correlated constructs as measured by the items designed to tap four

subskills.

The relationship among self-assessment, the MEPT, and the TOEFL iBT.

Once the factor structure was determined, a factor score of each subskill was

calculated for each participant and used in the follow-up correlation analysis. In

this study, standardized regression-based factor scores were calculated in Amos

21. The descriptive statistics for the three measures, namely the self-assessment,

the MEPT, and the TOEFL iBT, are listed in Table 8. Most of the scores from the

three measures were not normally distributed, as indicated by a significant

Shapiro-Wilk p value.

The EPT test administered in the spring 2014 semester was a revised version of the

MEPT test used in the fall 2013 semester. The two versions of the MEPT were

mainly different in terms number of items in the reading and listening sections (25

in 2013 vs. 35 in 2014). To examine the relationship among the three measures, the

correlation coefficients among these measures were calculated for the fall 2013 and

spring 2014 semesters separately. The sample sizes in the correlation analyses were

only 56 in 2013 and 62 in 2014 because there were some missing data in the three

measures. The cases with missing data were deleted listwise for correlation

analysis. Spearman’s rho was reported for the correlation that involves the MEPT

writing scores and Pearson’s r was used for other correlations.

82 Z. Li

Table 8. Descriptive statistics for the three measures

Test Section N M S.D Skewness Kurtosis Shapiro-Wilk

p value

MEPT

a

Reading 166 51.30 13.10 0.10 -0.23 .261

Listening 166 51.93 16.32 0.35 -0.35 .104

Writing 178 1.61 0.57 0.28 -0.75 .000

TOEFL

Reading 146 17.97 7.65 -0.35 -1.04 .044

Listening 146 17.10 7.08 -0.44 -1.02 .051

Speaking 146 16.39 6.10 -0.89 -0.63 .000

Writing 146 17.63 7.02 -0.84 -0.74 .001

Total 115 82.28 10.05 0.23 -0.67 .025

SA

b

Reading 181 0 0.62 -0.68 1.57 .000

Listening 181 0 0.82 -0.65 0.79 .001

Speaking 181 0 0.86 -0.54 0.42 .012

Writing 181 0 0.73 -0.44 0.62 .033

Note: a. The scores of reading and listening sections of the MEPT were converted to a 100-point

scale. b. The scores of the self-assessment sections were standardized factor scores.

The multitrait-multimethod matrices with raw correlation coefficients for the fall

2013 semester and the spring 2014 semester are shown in Tables 9 and 10,

respectively, which are color-coded for three types of correlations: heterotrait-

monomethod correlations in yellow, heterotrait-heteromethod correlations in blue,

and monotrait-heteromethod correlations in green. In addition, the reliability

information, if available, is listed on the diagonal line. The correlation coefficients

of interest in this study were the monotrait-heteromethod correlations because

they revealed the relationship among the measures of the same subskills. In other

words, they represent the evidence of convergent validity.

As shown in Table 9, the correlation coefficients between the self-assessment

sections and the MEPT in the spring 2014 semester were relatively low in the

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 83

monotrait-heteromethod cells, ranging from .150 to .373. Even after taking account

of the low reliability of the MEPT (.62 and .69 for the reading and listening

sections), the disattenuated correlation coefficients in the monotrait-heteromethod

cells were only slightly higher than the raw correlation coefficients (.264 vs. .193 for

reading subskill and .192 vs. .150 for the listening subskills). The highest

correlation coefficient was between the writing subskills measured by the MEPT

and the self-assessment and it is statistically significant (.373). Overall, the

magnitude of these correlation coefficients suggests that the self-assessment

sections had a relatively weak to moderate relationship with the corresponding

MEPT sections and that the self-assessment items may have measured somewhat

different constructs compared with the corresponding MEPT sections. However,

the significant correlation coefficient between the writing subskills measured by

self-assessment and the MEPT indicates that students’ self-assessment had a

relatively stronger relationship with their earlier performances on the MEPT

writing section. This may reflect the characteristics of the participants, the majority

of whom were placed into different levels of academic English writing classes with

only a small number placed in either ESL reading classes or listening classes.

The correlation coefficients in the heterotrait-heteromethod cells between the self-

assessment sections and the MEPT in the spring 2014 semester were relatively

higher, ranging from .168 to .424. The heterotrait-heteromethod correlations are

related with the discriminant validity and they are expected to be relatively lower

than the monotrait-heteromethod correlations. It is noteworthy that the correlation

coefficients (Spearman’s rho) between the writing section of the MEPT and other

sections of the self-assessment were all statistically significant (.350 to .424). This, to

some extent, lends support to the speculation that the self-assessment items at least

reflected participants’ proficiency in English writing. Overall, students’ self-

assessment exhibited some significant correlation with the MEPT, even though the

overall relationship between them was relatively weak.

The monotrait-heteromethod correlations of the same subskills between the self-

assessment sections and the TOEFL iBT sections in the spring 2014 semester

ranged from .120 to .368. The disattenuated correlation coefficients for the reading

and listening subskills are .136 and .272, respectively. This is similar to the

correlation coefficient pattern between the MEPT and the self-assessment.

Nevertheless, a noticeable difference is that the correlations between the TOEFL

iBT speaking and the four subskills in the self-assessment were all statistically

significant, ranging from .314 to .369 while the correlations between the TOEFL iBT

writing and the four subskills in the self-assessment were not (.208 to .216). Among

84 Z. Li

the heterotrait-heteromethod correlation coefficients, the reading self-assessment

had a statistically significant correlation with the TOEFL iBT listening section

(.293). Participants’ self-assessment exhibited some significant correlation with the

TOEFL iBT, even the overall relationship between them was relatively weak.

The heterotrait-monomethod correlations among the self-assessment sections were

very high, ranging from .857 to .956. This test method effect is in line with the

findings in Bachman and Palmer (1981). The heterotrait-monomethod correlations

among the MEPT sections were moderate, ranging from .316 to .504. The

heterotrait-monomethod correlations among the TOEFL iBT sections varied from -

.067 to .631.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 85

Table 9. Mutlitrait-multimethod correlation matrix for the spring 2014 data (N=62)

Self-assessment (SA) MEPT TOEFL iBT

Rd

a

Lsn Spk Wrt Rd Lsn Wrt Rd Lsn Spk Wrt

SA

Rd (.87)

Lsn .922**

b

(.88)

c

Spk .857** .923** (.91)

Wrt .890** .884** .956** (.89)

MEPT

Rd .193

a

.250 .283* .248 (.62)

Lsn .168 .150 .171 .168 .504** (.69)

Wrt .350** .397** .424** .373** .325* .316* (n/a)

TOEFL iBT

Rd .120 .014 .040 -.030 -.008 .265* .056 (.90)

Lsn .293* .230 .165 .176 .064 .336* .025 .631** (.81)

Spk .314* .369** .368** .317* .416** .345** .293* -.067 .149 (n/a)

Wrt .216 .208 .209 .215 .275* .467** .302* .189 .103 .369** (n/a)

Total .322* .263* .212 .224 .152 .524** .227 .800** .801** .404** .536**

Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01. a. Factor score for each subscale of the self-assessment was used in the correlation analyses. b. The correlation coefficients

associated with METP writing are Spearman’s rho and the other correlation coefficients are Pearson’s r. All the correlation coefficients are raw

correlation without correction for attenuation. c. The reliability of each test, if available, is listed on the diagonal. The reliability of the TOEFL iBT

subsection is an estimated KR21 reliability using mean and standard deviation assuming the number of item is 30.

86 Z. Li

Table 10. Mutlitrait-multimethod correlation matrix for the fall 2013 data (N=56)

Self-assessment (SA) MEPT TOEFL iBT

Rd

a

Lsn Spk Wrt Rd Lsn Wrt Rd Lsn Spk Wrt

SA

Rd (.87)

Lsn .901**

b

(.88)

c

Spk .658** .944** (.91)

Wrt .802** .857** .899** (.89)

MEPT

Rd .009

a

.033 .102 .052 (.60)

Lsn .172 .142 .078 .127 .446** (.69)

Wrt -.071 -.098 -.035 -.026 .307* .003* (n/a)

TOEFL iBT

Rd .208 .076 -.009 -.120 .378** .127 .378** (.90)

Lsn .183 .197 .136 .115 .552** .356** .228 .633** (.81)

Spk -.067 -.062 .053 -.029 .332* .208 .391** .001 .184 (n/a)

Wrt .163 .132 .144 .171 .146 .147 339* .170 .230 .470** (n/a)

Total .217 .144 .112 .150 .520** .308* .394** .786** .851** .431** .571**

Note: * p < .05, ** p < .01. a. Factor score for each subscale of the self-assessment was used in the correlation analyses. b. The correlation coefficients

associated with METP writing are Spearman’s rho and the other correlation coefficients are Pearson’s r. All the correlation coefficients are raw

correlation without correction for attenuation. c. The reliability of each test, if available, is listed on the diagonal. The reliability of the TOEFL iBT

section is an estimated KR21 reliability using mean and standard deviation assuming the number of item is 30.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 87

By comparison, two of the monotrait-heteromethod correlation coefficients

between the MEPT listening and writing sections and the corresponding the

TOEFL iBT sections in the spring 2014 semester were also low in magnitude but

statistically significant (.336 and .302). However, the correlation between the MEPT

reading and the TOEFL iBT reading section in the spring 2014 semester was

extremely low (-.008). It appears that the MEPT also had a relatively weak

relationship with the TOEFL iBT scores at least for this sample student group in

2014.

A closer look at the multitrait-multimethod matrix in Table 10 reveals that the

relationship between the self-assessment and the MEPT in the fall 2013 semester

was even weaker as none of the monotrait-heteromethod correlation coefficients

between them were statistically significant (-.026 to .142). However, this is

understandable given the time which had elapsed between the two measures

(more than one semester). Similarly, the relationship between the self-assessment

and the TOEFL iBT scores was weaker and the monotrait-heteromethod correlation

coefficients between them were slightly higher than those between the self-

assessment and the MEPT in the fall 2013 semester but still not statistically

significant (.053 to .208).

The monotrait-heteromethod correlation coefficients between the MEPT in 2013

and the TOEFL iBT sections were higher than those between the MEPT in 2014 and

the TOEFL iBT sections. Furthermore, the correlation coefficient between the

reading skills measured by the MEPT 2013 and the TOEFL iBT was .378, which is

similar to the correlation coefficients between listening and writing measured with

the MEPT 2013 and the TOEFL iBT. These differences in the correlation coefficients

between the two administrations of the MEPT test and the TOEFL iBT sections

suggest that the MEPT versions used in 2013 and 2014 may have tapped into the

same constructs in different ways.

There are several factors that can affect the relationship among the three measures.

Firstly, the constructs measured with the self-assessment were not necessarily the

same as the ones measured by the MEPT. All the can-do statements in the self-

assessment were phrased with a clear reference to specific academic activities at

the university, such as reading textbook and maintaining discussion with

classmates. Students may have evaluated their English proficiency globally in

these academic activities. On the other hand, the constructs defined in the

specifications of the MEPT and the TOEFL iBT may be different. What’s more, the

MEPT items as well as the TOEFL iBT items may have tested specific linguistic

skills in a more analytic way.

Z. Li

88

Secondly, the sample sizes in the correlation analyses with the MEPT tests in 2014

and 2013 were only 62 and 56, respectively. Therefore, the samples may

underrepresent the population and the resultant English proficiency range was

narrower, which may lead to the low correlation. This is evident when the

monotrait-heteromethod correlations between the MEPT and the TOEFL iBT in

2014 in this study (n= 62) are compared with a larger data set in the same MEPT

administration (n= 129). The correlations in the large data set were .220 for

reading, .453 for listening, and .403 for writing, whereas the correlations in the

smaller sample in this study were -.008 for reading, .336 for listening, and .302 for

writing.

Finally, the time interval between the self-assessment and other two measures is

critical in reflecting students’ English proficiency. The self-assessment was

administered in weeks six and seven of the spring semester in 2014, which means

the participants who took the MEPT in 2014 had spent about one and half months

in various English-medium classrooms at the university. This immersion may have

helped students improve their English at different rates and this improvement may

have affected the correlation between students’ self-assessment and their MEPT

scores and TOEFL iBT scores, which were received much earlier than the self-

assessment.

Considering the confounding factors discussed above, it is less surprising to see

the low correlation coefficients between the self-assessments and the MEPT and

the TOEFL iBT. Overall, the self-assessment had relatively weak to moderate

relationships with the MEPT and the TOEFL iBT in this study. However, the

existence of the significant correlation coefficients between the self-assessment and

other two measures still suggests a limited but promising utility of the self-

assessment as a tool to validate the MEPT.

Conclusions and Implications

The results of Rasch model-based item analysis indicated that the self-assessment

items exhibited acceptable reliabilities and good item discrimination. There were

no misfitting items in the self-assessment and the Likert scale used in the self-

assessment functioned well as the Rasch rating scale model expected. The results

from confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the correlated four-factor model

fitted the data and the proposed four-factor structure of the self-assessment was

supported. The multitrait-multimethod analyses indicated that the self-assessment

had relatively weak to moderate relationships with both the MEPT and the TOEFL

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 89

iBT, even though there were some significant correlations between the self-

assessment and some sections of the MEPT and the TOEFL iBT in the data of 2014

spring semester.

Admittedly, the results in this study call for a cautious use of the same self-

assessment tool in future validation studies of the MEPT. As shown in the

descriptive statistics of the self-assessment items, the can-do statements seemed to

have low item measure of difficulty. Therefore, some revisions could be made to

cover more challenging academic tasks that require intensive English use. Future

studies need to reconsider the timing of the self-assessment. A shorter time gap

between the self-assessment and the MEPT may mitigate the immersion effect and

yield a more accurate reflection of ESL students’ English proficiency. Other

constructs, such as motivational factors and student academic achievements, could

be included to help interpret the self-assessment results as well as the relationship

among the three measures in a comprehensive way.

Despite the limitations, the self-assessment reported in this study appears to be a

promising tool with its acceptable psychometric quality and clear factor structure,

thus potentially useful in providing evidence for the extrapolation inference of the

MEPT score interpretation and use in future studies.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Volker Hegelheimer and Carol Chapelle for their generous

support and guidance in this study. I also thank the anonymous reviewers for their

insightful and constructive comments on an earlier version of this paper. Any

errors that remain are my own.

Z. Li

90

References

Alderson, J. C. (2005). Diagnosing foreign language proficiency: The interface between

learning and assessment. London, England: Continuum.

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (1981). A multitrait-multimethod investigation into

the construct validity of six tests of speaking and reading. In A. S. Palmer, J.

D. Groot, & G. Tropser (Eds.), The construct validation of tests of communicative

competence, TESOL ’79 , February 27- 28, 1979. Boston.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: John

Wiley & Sons.

Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2007). Applying the Rasch model: Fundamental measurement

in the human sciences (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bradshaw, J. (1990). Test-takers’ reactions to a placement test. Language Testing,

7(1), 13–30.

Brantmeier, C. (2006). Advanced L2 learners and reading placement: Self-

assessment, CBT, and subsequent performance. System, 34(1), 15–35.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York and

London: The Guilford Press.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with Amos (2nd ed.). New York:

Routledge.

Chapelle, C., Enright, M. K., & Jamieson, J. (2008). Building a validity argument for

the Test of English as a Foreign Language. New York and London: Routledge.

Engelhardt, M., & Pfingsthorn, J. (2013). Self-assessment and placement tests – a

worthwhile combination? Language Learning in Higher Education, 2(1), 75–89.

Enright, M. K., Bridgeman, B., Eignor, D., Lee, Y.-W., & Powers, D. E. (2008).

Prototyping measures of listening, reading, speaking, and writing. In C. A.

Chapelle, M. K. Enright, & J. Jamieson (Eds.), Building a validity argument for

the Test of English as a Foreign Language (pp. 145–186). New York and

London: Routledge.

Fox, J. D. (2009). Moderating top-down policy impact and supporting EAP

curricular renewal: Exploring the potential of diagnostic assessment. Journal

of English for Academic Purposes, 8(1), 26–42.

Graham, J. G. (1987). English language proficiency and the prediction of academic

success. TESOL Quarterly, 21(3), 505–521.

Green, A. B., & Weir, C. J. (2004). Can placement tests inform instructional

decisions? Language Testing, 21(4), 467–494.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 91

Green, R. (2013). Statistical analyses for language testers. New York: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Hellekjær, G. O. (2009). Academic English reading proficiency at the university

level: A Norwegian case study. Reading in a Foreign Language, 21, 198–222.

IBM Corp. (2012). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY:

IBM Corp.

Kane, M. T. (2013). Validating the interpretations and uses of test scores. Journal of

Educational Measurement, 50(1), 1–73.

Knoch, U., & Elder, C. (2013). A framework for validating post-entry language

assessments (PELAs). Papers in Language Testing and Assessment, 2(1), 48–66.

Kokhan, K. (2012). Investigating the possibility of using TOEFL scores for

university ESL decision-making: Placement trends and effect of time lag.

Language Testing, 29(2), 291–308.

Kokhan, K. (2013). An argument against using standardized test scores for

placement of international undergraduate students in English as a Second

Language (ESL) courses. Language Testing, 30(4), 467–489.

Le, H. T. T. (2010). Developing a validity argument for the English placement Fall 2010

Listening test at Iowa State University. Unpublished MA thesis, Iowa State

University. Ames, Iowa.

LeBlanc, R., & Painchaud, G. (1985). Self-assessment as a second language

placement instrument. TESOL Quarterly, 19(4), 673–687.

Lee, Y.-J., & Greene, J. (2007). The predictive validity of an ESL placement test: A

mixed methods approach. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(4), 366–389.

Leung, S.-O. (2011). A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-,

5-, 6-, and 11-point likert scales. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(4), 412–

421.

Light, R. L., Xu, M., & Mossop, J. (1987). English proficiency and academic

performance of international students. TESOL Quarterly, 21(2), 251–261.

Linacre, J. M. (2011). A User’s Guide to Winstep. Ministep Rasch-Model Computer

Programs. Chicago, IL.

Luoma, S. (2013). Self-assessment. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of

Applied Linguistics. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Z. Li

92

Malabonga, V., Kenyon, D. M., & Carpenter, H. (2005). Self-assessment,

preparation and response time on a computerized oral proficiency test.

Language Testing, 22(1), 59–92.

Manganello, M. (2011). Correlations in the new TOEFL era: an investigation of the

statistical relationships between iBT scores, placement test performance, and

academic success of international students at Iowa State University. Unpublished

MA thesis, Iowa State University. Ames, Iowa.

Oscarson, M. (2013). Self-assessment in the classroom. In A. Kunnan (Ed.), The

companion to language assessment vol. II: Approaches and development (pp. 712–

729). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Phakiti, A., Hirsh, D., & Woodrow, L. (2013). It’s not only English: Effects of other

individual factors on English language learning and academic learning of

ESL international students in Australia. Journal of Research in International

Education, 12(3), 239–258.

Riazi, M. (2013). Concurrent and predictive validity of Pearson Test of English

Academic (PTE Academic). Papers in Language Testing and Assessment, 2(1),

1–27.

Ross, S. (1998). Self-assessment in second language testing: a meta-analysis and

analysis of experiential factors. Language Testing, 15(1), 1–20.

Sawaki, Y., Stricker, L. J., & Oranje, A. (2009). Factor structure of the TOEFL

Internet-based test. Language Testing, 26(1), 5–30.

Song, M. (2008). Do divisible subskills exist in second language (L2)

comprehension? A structural equation modelling approach. Language

Testing, 25(4), 435–464.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Boston:

Pearson Education Inc.

Vinke, A. A., & Jochems, W. M. G. (1992). English proficiency and academic

success in international postgraduate education. Higher Education, 26(3),

275–85.

Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research: A

content analysis and recommendations for best practices. The Counseling

Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838.

Yang, H., & Li, Z. (2013). Validating an English placement by investigating factor

structure and factorial invariance. Paper presented at the 15th annual

Midwest Association of Language Testers (MwALT) conference. East

Lansing, MI.: Michigan State University.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 93

Appendix

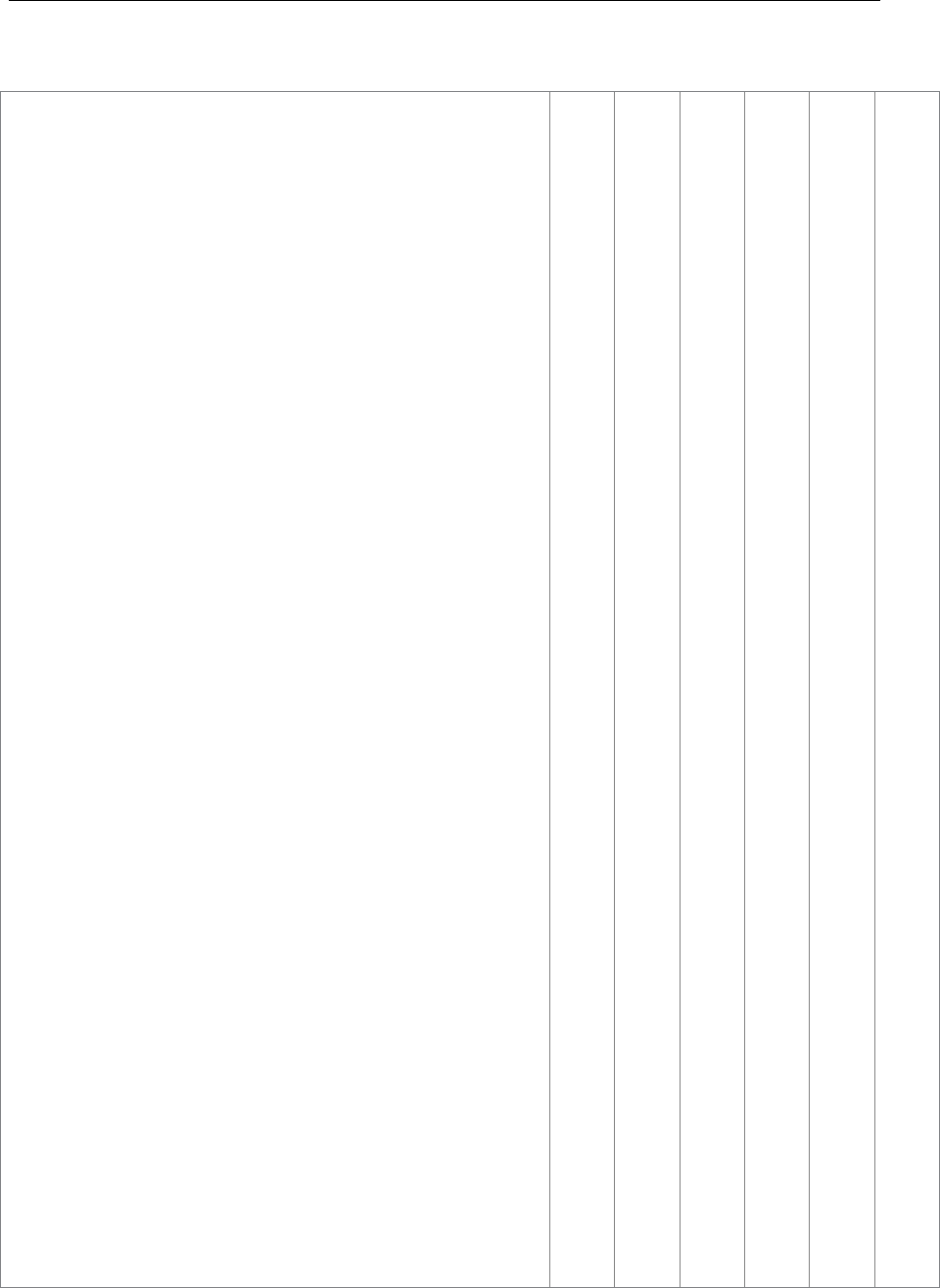

Self-assessment of English use in your non-ESL courses or major courses

Instructions: In this section, you are asked to think about your English use in one

required general education or major course you are taking this semesters,

Please therefore think of one course you are currently taking in your major or for

required general education credits (so not an ESL course) and write it here (for

example, Psych 101). Now please respond to the following statements about your

English experience in this course.

Below are some self-assessment statements about your use of English in the above-

listed major course. Please rate the following statements based on your own

experience.

Z. Li

94

Stron

gly

Disag

ree

Disag

ree

Some

what

Disag

ree

Some

what

Agree

Agree Stron

gly

Agree

1. I can read and understand the syllabus,

assignment sheets, equipment/software

instructions and other course materials without

any help.

2. I can find important details in my textbook,

handouts, technical manuals, and other course

materials quickly by skimming and scanning

(reading quickly).

3. I can distinguish main ideas and supporting

examples in my textbooks and other reading

materials in my major course(s).

4. I can successfully guess the meaning of

unfamiliar words or idioms (set phrases) in my

textbooks or other course materials without using

a dictionary.

5. I can identify opinions that are only suggested

or implied, as well as opinions that are clearly

stated in a textbook and/or other course materials.

6. I can understand the main ideas of lectures,

professional presentations and spoken reports in

my major.

7. I can understand lectures even when my teacher

speaks very fast.

8. I can understand the English in non-subtitled

English video tutorials/lessons on topics that are

connected to my major.

Papers in Language Testing and Assessment Vol. 4, issue 1, 2015 95

9. I can easily understand my American

classmates in group discussions or pair work in

my major course(s).

10. I can predict the upcoming content or topic in

a class based on what my teacher has talked about

so far.

11. I can successfully talk on the phone in English

to ask and answer questions about campus life

and events.

12. I can start and maintain a discussion orally

with my classmates in an in-class activity.

13. I can use English to provide a spoken

summary of long and difficult course materials for

my classmates and teacher.

14. I can express complex ideas to my classmates

and my teacher providing strong supporting

evidence as needed.

15. I can make a clearly developed presentation on

a topic in my major using fluent and accurate

English.

16. I can write a report or do a course assignment

using correct grammar and academic style.

17. I can communicate disagreement

appropriately with my teacher in email in a

formal and polite way.

18. I can revise and edit my own writing

(including class assignments and/or papers for

publication) to make it better and more acceptable

Z. Li

96

to my teacher or advisor.

19. I can use different language styles and

vocabulary in writing appropriate for different

readers (for example, friends, classmates, teachers,

etc.).

20. I can use and include external sources (for

example, articles and reports) appropriately in my

own writing through summarizing, quoting, and

paraphrasing them.

21. I can write an essay with a clear paragraph

structure by using topic sentences and supporting

details.