Walden University Walden University

ScholarWorks ScholarWorks

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection

2022

The Relationship Between Employee Engagement, Job The Relationship Between Employee Engagement, Job

Satisfaction, And Employee Performance in The Federal Satisfaction, And Employee Performance in The Federal

Government Government

Alexis L. Shellow

Walden University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations

Part of the Business Commons

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an

authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Walden University

College of Management and Technology

This is to certify that the doctoral study by

Alexis Shellow

has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by

the review committee have been made.

Review Committee

Dr. Colleen Paeplow, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Dr. Matasha Murrell Jones, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Dr. Natalie Casale, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Chief Academic Officer and Provost

Sue Subocz, Ph.D.

Walden University

2022

Abstract

The Relationship Between Employee Engagement, Job Satisfaction, And Employee Performance

in The Federal Government

by

Alexis Shellow

MBA, Aurora University, 2018

BS, Westminster College, 2015

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration Secondary Data Analysis Portfolio

Walden University

August 2022

Abstract

Leaders in the U.S. Federal Government face performance challenges due to disengaged

employees and employees with low satisfaction. Leaders within the federal government need to

understand the relationship between employee engagement, job satisfaction, and employee

performance, as decreased employee performance can result in decreased productivity, increased

turnover, and have negative financial implications. Grounded in Herzberg’s two-factor theory

and Kahn’s engagement theory, the purpose of this quantitative correlational ex post facto study

was to examine the relationship between employee engagement, job satisfaction, and employee

performance within the federal government. Data from the 2019 Federal Employment Viewpoint

Survey (n = 100) were analyzed using multiple regression analysis. The multiple linear

regression analysis results indicated the model was able to significantly predict performance

F(2,97) = 43.836, p < .001, R

2

= .475. Employee engagement (t = 3.594, p < .001, β = .504) was

the only statistically significant predictor. A key recommendation for leaders in the federal

government to engage federal employees is to recognize employee achievements, create a work

environment promoting psychological safety, provide employees with adequate resources, and

have well-defined roles and responsibilities for employees while allowing them to exercise

autonomy in their work processes. The implications for positive social change include the

potential for cost savings, helping leaders in the federal government assess areas of

improvement, creating a more productive environment for improved employee performance, and

increasing employee retention and job satisfaction in the workforce.

The Relationship Between Employee Engagement, Job Satisfaction, And Employee Performance

in The Federal Government

by

Alexis Shellow

MBA, Aurora University, 2018

B.S., Westminster College, 2015

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration Doctor of Business Administration Secondary Data Analysis

Portfolio

Walden University

August 2022

Dedication

I want to dedicate my work to my family and friends who have supported me along this

journey; I love and appreciate all of you and would not have been able to do this without you. To

my mother, thank you for instilling in me the importance of hard work, perseverance, and

dedication. To my father, thank you for all the love and support you have shown me through my

journey. To my Gantzy, for showing me what it means to be strong and always welcoming me

with the warmest love. To all my siblings, who have been constant sources of love and support,

and continue to inspire me every day, thank you and I love you. To my Aunt Michelle, I don’t

know where I would be without your constant love, grace, and motivation. To my Uncle Myke,

for always believing in me and providing everything I needed whenever I needed it. To my

Uncle Jay for showing me the importance of following my passions and never giving up on

myself. To my Uncle Corey for always moving mountains to help me become successful. I

would not be where I am today without the love and support I have received from all of you.

Lastly, I would like to dedicate this work to the neurodivergent population. I have

struggled a lot with understanding my abilities and would often limit myself out of fear of failure

and societal perceptions. I hope it serves as a reminder and as motivation that we can do

extraordinary things, including everything that society has told us we couldn’t.

Acknowledgments

I want to extend a special thank you to all my friends, family, colleagues, and mentors.

Without you all, I would not have made it through this doctoral program. To my Chair, Dr.

Colleen Paeplow, thank you for giving me great instruction and guidance, while motivating and

mentoring me along the way. You have shown me so much patience, kindness, and empathy

throughout this journey and I am grateful to be one of your students. To Dr. George Bradley, Dr.

Jaime Klein, Dr. Natalie Casale, and Dr. Matasha Murrelljones, thank you for being a part of my

committee; your feedback and support have helped me to go the extra mile for my study. To my

friend and sister, Courtney, thank you for your unconditional love and support.

A special word of love and gratitude to my partner, Desmond, for being my rock as I

finished my study. Dr. Camille Black, we went through this journey together and you have been

my sounding board and have become one of my best and dearest friends. To my good friend

Chris, thank you for your continuous support and for always being that shoulder when I needed

it. To my amazing friend and greatest supporter, Dee, thank you for your constant reassurance

and for making sure I had everything I needed to finish this doctoral study. To my mentor and

my biggest advocate, Tonya Lovelace. You have pushed, encouraged, motivated, and inspired

me in so many ways. You continue to show up and support me, always willing to make sure I

have what I need to be successful. You’ve taught me the importance of speaking up and what it

means to be a great leader. Words can’t fully express my gratitude, but I thank you for pouring

into me and for everything you do.

i

Table of Contents

List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... iv

List of Figures ......................................................................................................................v

Section 1: Background and Content ....................................................................................1

Historical Background ...................................................................................................1

Organizational Context ..................................................................................................3

Problem Statement .........................................................................................................4

Purpose Statement ..........................................................................................................5

Target Audience .............................................................................................................6

Research Question .........................................................................................................6

Data Collection and Analysis.................................................................................. 7

Significance....................................................................................................................7

Theoretical Framework ..................................................................................................9

Representative Literature Review ................................................................................11

Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................13

Herzberg’s Two Factor Theory ............................................................................. 14

Kahn’s Engagement Theory ................................................................................. 18

Alternate Theories ................................................................................................. 33

Problem ........................................................................................................................40

Employee Engagement ......................................................................................... 42

Job Satisfaction ..................................................................................................... 49

Employee Performance ......................................................................................... 61

ii

Transition .....................................................................................................................64

Section 2: Project Design and Process ...............................................................................67

Method and Design ......................................................................................................67

Method .................................................................................................................. 68

Design ................................................................................................................... 69

Ethics ................................................................................................................... 71

Transition and Summary ..............................................................................................71

Section 3: The Deliverable .................................................................................................73

The Deliverable ............................................................................................................73

Executive Summary .....................................................................................................73

Goals and Objectives ............................................................................................ 75

Overview of Findings ........................................................................................... 75

Recommendations ................................................................................................. 77

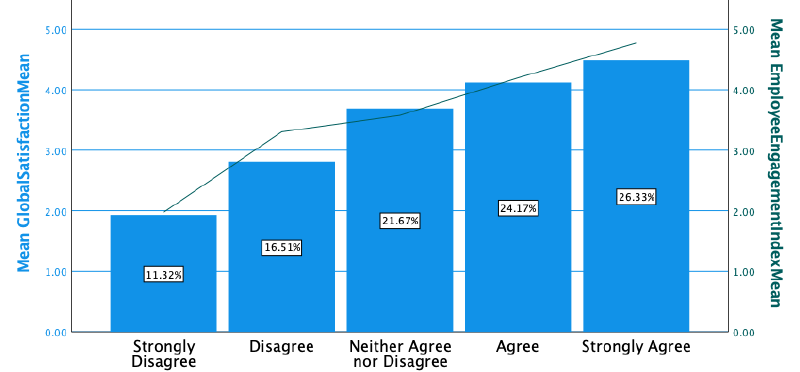

Presentation of Quantitative Data Analysis .................................................................78

Descriptive Statistics ............................................................................................. 78

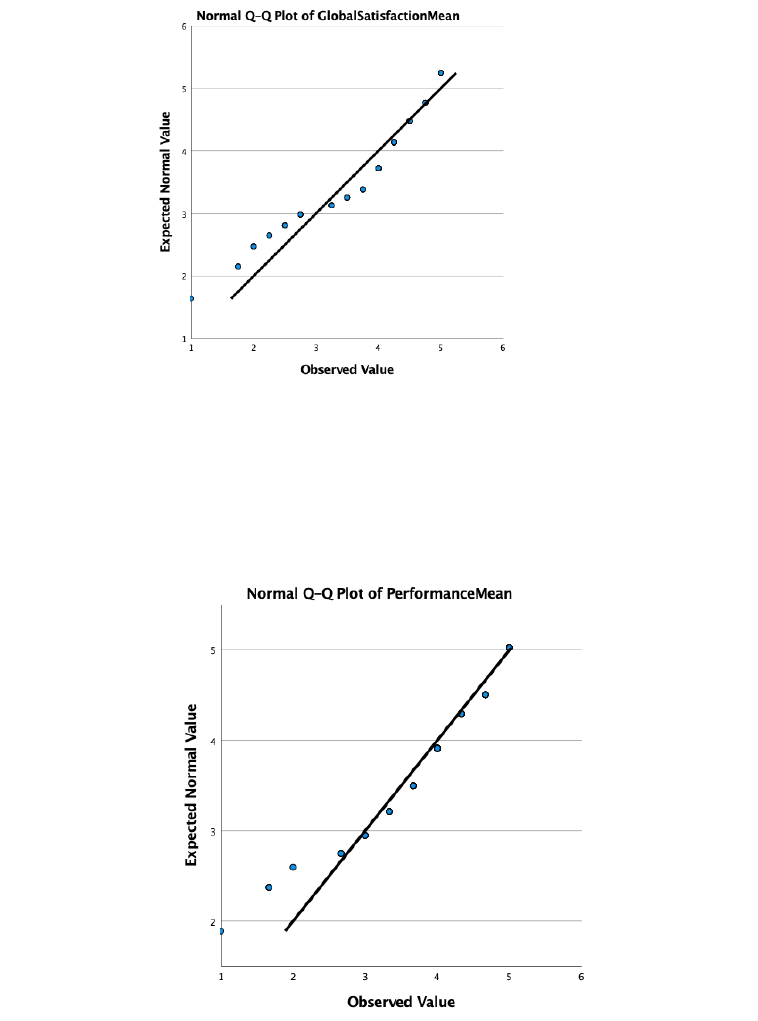

Statistical Tests of Assumptions ........................................................................... 81

Inferential Statistical Analysis .............................................................................. 88

Results and Conclusions of Data Analysis ................................................................100

Recommendations for Action ....................................................................................117

Communication Plan ..................................................................................................120

Social Change Impact ................................................................................................121

Skills and Competencies ............................................................................................124

iii

References ........................................................................................................................125

Appendix A: Secondary Dataset Sources ........................................................................156

Appendix B: Employee Engagement Index, Global Satisfaction Index, Employee

Performance .........................................................................................................157

iv

List of Tables

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables .......................................................... 81

Table 2. Gender, Minority, Education, Supervisory Status, and Years in Service ........... 81

Table 3. Multiple Model Regression Summary ................................................................ 82

Table 4. Tests for Normality ............................................................................................. 87

Table 5. Multiple Regression Model Summary ................................................................ 91

Table 6. ANOVA Summary ............................................................................................. 92

Table 7. Coefficients ......................................................................................................... 92

Table 8. Correlations of Study Variables While Controlling for Employee Engagement 94

Table 9. Analysis of Response Frequencies on Employee Engagement .......................... 97

Table 10. Analysis of Response Frequencies for Job Satisfaction ................................... 99

Table 11. Analysis of Response Frequencies for Employee Performance ..................... 100

Table B1. Employee Engagement Index ........................................................................ 157

Table B2. Global Satisfaction Index ............................................................................... 157

Table B3. Employee Performance Driver ....................................................................... 158

v

List of Figures

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework ..................................................................................... 11

Figure 2. Power Prior Analysis ......................................................................................... 80

Figure 3. Linearity Between Study Variables ................................................................... 83

Figure 4. Linearity between Employee Performance and Job Satisfaction ...................... 84

Figure 5. Linearity Between Employee Performance and Employee Engagement .......... 85

Figure 6. Normal Q-Q Plot of Studentized Residuals....................................................... 87

Figure 7. Employee Engagement Influencers ................................................................. 103

Figure 8. Mediator Variable ............................................................................................ 106

Figure 9. Motivation and Hygiene Factors ..................................................................... 107

Figure 10. I Feel Encouraged to Come up with New Ways of Doing Things ................ 110

Figure 11. When Needed I am Willing to Put in the Extra Effort to get a Job Done ..... 111

Figure 12. I Have Trust and Confidence in My Supervisor ............................................ 112

Figure 13. Are You Considering Leaving your Organization and Why? ....................... 113

Figure 14. Normal Q-Q Plot of Studentized Residual .................................................... 115

Figure 15. Q-Q Normality Plot of Employee Engagement............................................. 115

Figure 16. Q-Q Normality Plot of Employee Satisfaction .............................................. 116

Figure 17. Q-Q Normality Plot of Employee Performance ............................................ 116

1

Section 1: Background and Content

Historical Background

Employee performance is critical in maximizing organizational effectiveness

(Gruman & Saks, 2011). Highly performing employees are more likely to develop

innovative ideas to help the organization operate more efficiently (Copeland, 2020). To

improve employee performance, the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM)

created a human capital framework to promote performance culture and engage, develop,

and inspire a diverse, high-performing workforce by designing, implementing, and

maintaining effective performance management strategies, practices, and activities that

support mission objectives (OPM, 2016). Employee engagement and job satisfaction

influence employee performance (Osborne & Hammoud, 2017), and employee

engagement is considered essential to business success within many federal agencies

(Lavigna, 2019).

The OPM has partnered with leaders across government agencies to support data-

driven changes to improve employee engagement, leading to organizational success. The

Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey (FEVS) provides vital data regarding the employee

work experience (Shih, 2020), measuring employee engagement, and assessing

engagement drivers (OPM, 2016). Each year, OPM administers the FEVS to measure

employees’ perceptions of whether and to what extent successful organizations’

conditions and characteristics are present in their agencies. OPM conducts the FEVS to

identify areas of improvement in the federal government.

2

Additionally, the OPM created an Employee Engagement Index (EEI) in 2010 to

assess the factors that impact employee engagement and identify engagement potential

within organizations (OPM, 2016). Items 3, 4, 6, 11, 12, 47–49, 51–54, 56, 60, and 61

make up the FEVS EEI. From 2010 to 2019, the average score among federal employees

on the EEI increased from 66% to 68% (Hameduddin & Fernandez, 2019; OPM, 2019),

with the lowest average score of 63% occurring in 2014 (Hameduddin & Fernandez,

2019; OPM, 2019). Organizational leaders can use this information to determine whether

their engagement strategies need improvement (OPM, 2016).

In 2015, OPM introduced the Employee Engagement Initiative to address

employee engagement issues within federal agencies (OPM, 2015). The initiative

emphasizes creating organizational conditions that foster employee engagement (OPM,

2016), expecting increased engagement to improve performance. (Kamensky, 2020).

Research suggests that high levels of employee engagement augment employees’ job

performance (Christian et al., 2011; Leiter & Bakker, 2010; Partnership for Public

Service, 2019). As the factors that influence employee engagement increase, employee

and organizational performance increases resulting in a direct positive relationship

between engagement and performance (Ahmed et al., 2016; Arifin et al., 2019).

Employee engagement levels can impact the overall health and performance of an

organization (McCarthy et al., 2020). Engaged employees contributes to lower employee

turnover (Bhatt & Sharma, 2019). In contrast, lack of employee engagement (McCarthy

et al., 2020) relates to low job satisfaction (Barden, 2017; Jin et al., 2016; McCarthy et

3

al., 2020), and low employee engagement and low job satisfaction can negatively

influence job performance (Osborne & Hammoud, 2017).

Using the FEVS to understand how employees feel about their job can help

human resource managers identify factors that increase employee engagement and job

satisfaction and how these variables relate to employee performance. The survey is

available to be taken online for 6 weeks. FEVS representatives recommend that

individual agencies compare their agencies with the overall results to understand better

how their employees feel about their jobs (OPM, 2018b). Employers need to have a

strong understanding of how the employees feel about their job, which can help human

resource managers and leaders determine how to help their employees stay engaged

(OPM, 2018b). Federal agencies can use this information to compare their results against

the total federal government. Combining the assessment of knowledge, skills, and

aptitudes required for the task with the organizational strategy can predict job satisfaction

and job performance (Paulo da Silva & Shinyashiki, 2014). An increase in an engaged

and satisfied workforce can increase job performance, reduce turnover (Byrne et al.,

2017; Paulo da Silva & Shinyashiki, 2014), and save organizations billions of dollars

annually (Barden, 2017).

Organizational Context

Each agency within the U.S. Federal Government has its own mission and vision.

However, OPM has determined that focusing on performance is essential to improving

the organization and meeting each agency’s mission and vision. Several governmentwide

initiatives have been implemented to assist agencies in reexamining and enhancing their

4

performance measures. The performance initiatives require agencies to set goals and

standards to align employee performance with agency goals (OPM, n.d.).

The FEVS is an annual assessment that OPM administers to evaluate employees’

perceptions of agency conditions that support success. The FEVS was designed to

provide agencies with employee feedback on factors that critically impact organizational

performance, such as perception of leadership, effectiveness, employee engagement, and

job satisfaction (Kamensky, 2020; Lappin, 2021; OPM, 2016). Some leaders at federal

agencies would create action plans to improve low-scoring items; however, this strategy

did not prove to improve employee satisfaction or engagement (Lappin, 2021;

Metzenbaum, 2019; OPM, n.d.). Furthermore, leaders in the federal government did not

understand the relationship between employee engagement, job satisfaction, and

employee performance (Lappin, 2021; Metzenbaum, 2019). This study explored

employee engagement, job satisfaction, and employee performance. Understanding the

relationship between these variables may help leaders create more efficient strategic

plans to improve employee performance.

Problem Statement

Low-performing employees reduce the team’s motivation and performance by

approximately 40% (Lee & Rhee, 2019), contributing to approximately $483 billion to

$605 billion in lost productivity each year in the United States (State of the American

Workplace, 2020). In addition, only 21% of employees in the United States feel that their

leadership manages their performance in a way that motivates them to do outstanding

work, and only 14% of employees are inspired to improve their performance (State of the

5

American Workplace, 2020). Research has shown that organizations with higher

employee engagement and job satisfaction demonstrate better performance (Bhatt &

Sharma, 2019; Budirianti et al., 2020; Cankir & Arikan, 2019; Concepcion, 2020; Gupta

& Sharma, 2016; Popli & Rizvi, 2015). The general business problem is a lack of

employee engagement, and low job satisfaction can result in low employee performance

(Osborne & Hammoud, 2017). The specific business problem that this study will address

is that leaders within the federal government do not understand the relationship between

employee engagement, job satisfaction, and employee performance among employees

within the federal government. The 2019 FEVS is the dataset that was used for this study

to examine whether a relationship exists between employee engagement, job satisfaction,

and employee performance among employees within the federal government.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this quantitative correlational ex post facto study was to examine

the relationship between employee engagement, job satisfaction, and employee

performance among employees within the federal government. I conducted secondary

data analysis using data obtained from the 2019 FEVS. The independent variables

identified in the FEVS were employee engagement, measured by the EEI in the 2019

FEVS, and job satisfaction, measured by the Global Satisfaction Index (GSI), Items 40

and 69–71. The dependent variable was employee performance, measured by the

Performance Driver in the 2019 FEVS, consisting of Items 15,16, and 19. Previous

researchers have tested and confirmed the validity of the composite variable or close

variations to measure both employee performance and organizational performance (Choi

6

& Rainey, 2020; Lee, 2018; Metzenbaum, 2019; Pitts, 2009; Somers, 2018). The

implications for social change include contributing to leadership practices by identifying

job satisfaction and employee engagement influencers and determining how performance

is related to those factors. This information can help leaders in the federal government

create a more productive environment for improved employee and business performance

and maximize resources (Hejjas et al., 2019), increasing employee retention and job

satisfaction (Bhatt & Sharma, 2019) in the workforce.

Target Audience

The key stakeholders in this portfolio were agencies within the federal

government, employees within the federal government, U.S. citizens, and leaders in the

federal government focusing on improving employee engagement and job satisfaction.

Determining the relationship between employee engagement, job satisfaction, and

employee performance can help leaders implement strategies to improve employee

performance. Understanding the relationship between these variables can also reduce

costs, increase retention, and enhance job satisfaction. Furthermore, government business

operations are primarily funded by taxpayer dollars, making U.S. citizens essential

stakeholders. Maximizing the use of resources can be a positive result for stakeholders as

they are ensured that their tax dollars are being utilized efficiently and responsibly.

Research Question

Does a significant relationship exist between employee engagement, job

satisfaction, and employee performance among employees within the federal

government?

7

H

0

: There is no statistically significant relationship between employee

engagement, job satisfaction, and employee performance among employees within the

federal government.

H

1

: There is a statistically significant relationship between employee engagement,

job satisfaction, and employee performance among employees within the federal

government.

Data Collection and Analysis

I collected data using an archival data collection technique. I extracted data from

the OPM FEVS 2019 Public Release Data File provided on the OPM government

website. I conducted a multiple regression analysis to determine a relationship between

this study’s independent and dependent variables. Multiple linear regression examines the

relationship between multiple independent variables and a dependent variable. The

degree to which the dependent variable, employee performance, is explained by the

independent variables job satisfaction and employee engagement was the focus of this

study.

Significance

The federal government is making a continuous effort to increase employee

performance (Pecino et al., 2019). The findings of this quantitative multiple regression

study can provide value to leaders in the federal government. It also provides a model for

understanding the degree to which employee engagement and job satisfaction relate to

employee performance. Employee engagement and job satisfaction are vital indicators for

predicting employee performance. Understanding this relationship may assist leaders

8

within the federal government indicate productivity and possibly turnover intent.

Furthermore, leaders may also determine what factors influence employee performance

and incorporate those factors to create and implement more effective practices and

strategies to maintain employee engagement to increase employee performance (OPM,

2016). By implementing successful strategies, leaders within the federal government

mitigate risks of low productivity, decreased work quality, rising costs, and increased

turnover.

The implications for positive social change include the potential to increase

employee performance and productivity (Osborne & Hammoud, 2017), maximize the use

of resources (Hejjas et al., 2019), and increase employee retention and job satisfaction

(Bhatt & Sharma, 2019), and save the organization costs (Osborne & Hammoud, 2017).

Increasing employee engagement can lead to increased job satisfaction and performance

and lower organizational turnover rates (Paulo da Silva & Shinyashiki, 2014).

Additionally, increased job satisfaction can positively influence creating more innovative

strategies to complete tasks and contribute to the organization's cost savings due to a

more efficient allocation of resources. Increased employee engagement increases job

satisfaction and job performance (Paulo da Silva & Shinyashiki, 2014) and saves

organizations billions of dollars annually (Barden, 2017). Thus, this study’s findings

could further inform the field by examining the degree to which employee engagement

and job satisfaction relate to employee performance.

9

Theoretical Framework

I used two theories as the framework for my study: Herzberg’s two-factor theory,

often referred to as Herzberg’s dual-factor theory (Alshmemri et al., 2017), to address the

relationship between job satisfaction and job performance, and Kahn’s employee

engagement theory to address the relationship between employee engagement and job

performance. Herzberg’s two-factor theory, also known as the motivation-hygiene theory

and Herzberg’s dual-factor theory (Herzberg, 1959), is a motivation theory influenced by

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Jones, 2011). Herzberg’s two-factor theory identifies two

sets of factors: hygiene and motivation factors that affect job satisfaction. Hygiene factors

include company policies, coworker relationships, salaries, and supervision (Herzberg,

1966). Herzberg’s theory proposes that motivation factors result in satisfaction, and

hygiene factors prevent dissatisfaction (Hur, 2017). Motivation factors include

recognition, achievement, advancement, the work itself, and growth (Herzberg, 1966). A

decrease in hygiene factors can cause employees to work less, whereas an increase in

motivating factors can encourage employees to work harder. The factors presented by

Herzberg influence performance by assessing motivational and hygiene factors.

The second theoretical framework I applied to this study is Kahn’s employee

engagement theory (Kahn, 1990). Kahn’s theory measures employee engagement through

employees’ level of commitment to their work roles and how organizations influence

engagement to the extent that employees engross themselves in their performance to

reach organizational objectives (Gupta & Sharma, 2016; Kahn, 1990; Vaijayanthi et al.,

2011). The starting point for Kahn’s (1990) engagement theory was the work of Goffman

10

(1961), which suggests that employee levels of attachment to their roles vary, and

employees can demonstrate various levels of attachment and detachment with each

moment. The theory presented by Goffman was attributed to fleeting encounters and not

a consistent organizational experience (Kahn, 1990). Kahn argued that Goffman’s work

did not fit organizational life and focused on face-to-face interactions (Gruman & Saks,

2011; Kular et al., 2008; Kahn, 1990). Kahn classifies this as self-in-role, meaning that

when employees are engaged, they keep themselves within the role they are performing

(Gruman & Saks, 2011; Kahn, 1990).

The employee engagement theory states that meaningfulness, safety, and

availability, influence employee engagement levels (Kahn, 1990). When employees are

involved and invested in their jobs, employee engagement increases. Alternatively, when

employees withdraw from their duties, engagement decreases. Employees’ perceptions of

their performance’s meaningfulness, availability of resources to successfully complete

their jobs, and perception of employee safety influence employee engagement.

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between employee

engagement, job satisfaction, and employee performance among employees within the

federal government. As applied to this study, the Herzberg two-step theory holds that I

would expect the independent variables to influence employee performance. The FEVS

(2019) identifies hygiene and motivation factors as influencers of employee performance

and engagement. Figure 1 depicts how each independent variable relates to the dependent

variable.

11

Figure 1

Theoretical Framework

Herzberg’s two-factor theory explains how job satisfaction relates to and explains

employee performance. Kahn’s employee engagement theory measures how employee

engagement influences employee and organizational performance (Kahn, 1990), which I

used to examine how employee engagement relates to and explains employee

performance (Albrecht et al., 2015).

Representative Literature Review

This literature review focuses on employee engagement and job satisfaction and

the relationship each variable has on employee performance. This literature review

contains comprehensive research from multiple business functions and applications to

describe a quantitative correlational study within the federal government. This literature

review was conducted to examine the relationship between the study’s independent

variables, employee engagement and job satisfaction, and the dependent variable,

employee performance amongst employees in the federal government.

12

I based the literature review on Herzberg’s (1959) two-factor theory and Kahn’s

(1990) engagement theory. The componential theory of creativity and social exchange

theory is also discussed in this literature review to provide further insight on the

expounding of the theories as time progressed. Herzberg’s two-factor theory most

adequately addresses job satisfaction’s impact on employee performance, and Kahn’s

engagement theory was best suited to address the relationship between employee

engagement and performance.

The literature reviewed for this study consisted of items published since 2017

with a few exceptions from beyond that time, as was necessary for a complete theoretical

foundation. The sources included in this section provide background, relevant theories,

contextual support, supporting data, and the impact on performance, productivity, and

profitability. I used Walden University’s library databases to research the literature,

providing a great deal of information on employee engagement and job satisfaction. For

research purposes, search terms consistent with this study were used, such as employee

engagement, job satisfaction, employee performance, organizational performance,

Federal Employment Viewpoint survey, resources and satisfaction, employee recognition,

employee dissatisfaction, disengaged employees, Maslow’s hierarchal theory, job

resources demand theory, self-determination theory, employee productivity, and burnout.

The purpose of the literature review was to identify and ascertain additional

information relative to the main factors of this study. An analysis of previously written

studies that focus on employee engagement, job satisfaction, and employee performance

are included—the foundation of the theoretical framework aided in completing this

13

section. Walden Library’s extensive databases accumulated peer-reviewed articles and

publications, specifically ABI/Inform Complete, Business Source Complete, and

EBSCOhost. Researching using the dissertations at Walden selection, mining other

authors’ reference sections, and keyword searching helped complete this review. I

exhausted the searches by using variations of the original terms to benefit from the

different tenses of the words by gaining additional resources such as satisfied,

satisfaction, satisfy, engage, engaged, engagement, engaging, motivate, motivation,

motivator, motivated, and motivating. I also utilized Google Scholar to identify relevant

sources I accessed using my Walden Library credentials.

Nine major themes, based on Herzberg et al.’s (1959) motivation-hygiene theory,

are included in this review. The themes included (a) achievement, (b) recognition, (c)

work itself, (d) responsibility, (e) advancement, (f) working conditions, (g) company

policies, (h) relations with supervisors, subordinates, or coworkers, and (i) pay. Three

major themes based on Kahn’s (1990) engagement theory are also included in this

literature review: (a) meaningfulness, (b) safety, and (c) availability. Applying these

factors to the variables included in the study and alternate theories is also discussed in the

literature review.

Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework helps structure and organize a study (Dziak, 2020). The

theoretical frameworks used for this study were Herzberg’s two factor theory and Kahn’s

employee and engagement theory. This section of the literature provides a critical

analysis and complete synthesis of the applicability, basis, various perspectives,

14

comparative research, and alternative theories of the frameworks used to structure this

study.

Herzberg’s Two Factor Theory

Herzberg conducted a study in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania using more than 200

engineers and accountants working in approximately nine different factories to explore

the factors contributing to employee job satisfaction and motivation (Herzberg et al.,

1959). Based in this research, Herzberg concluded that the factors affecting job

satisfaction consist of two categories: motivation factors and hygiene factors. Motivation

factors, or satisfiers, are considered intrinsic factors associated with the need for growth

or self-actualization (Herzberg, 1966). The factors that make up positive attitudes for

employee engagement and job satisfaction include achievement, recognition, the work

itself, responsibility, advancement, and the possibility for growth (Herzberg, 1966).

Hygiene factors, also known as dissatisfiers, are considered extrinsic factors. The

factors that comprise the negative job attitudes attributed to disengagement and

dissatisfaction include company policies, coworker relationships, salaries, working

conditions, and supervision (Herzberg et al., 1959). Low hygiene factors in an

organization can lead to higher employee dissatisfaction, which can cause employees to

work less. Alternatively, increasing motivating factors can encourage employees to work

harder by influencing their attitudes (Herzberg, 1966). Essentially, motivation factors

work to improve job satisfaction, and hygiene factors work to reduce job dissatisfaction.

But satisfaction and dissatisfaction are not on the same continuum, as each is affected by

different factors and is independent of one another.

15

Although hygiene factors and motivator factors influence employee satisfaction,

they do so differently. Lack of hygiene factors leads to dissatisfaction from the job’s

extrinsic conditions, making the employee unhappy with the job conditions (Herzberg,

1968). The employee can be disgruntled with the job conditions but still enjoy the work.

However, satisfying hygiene requirements is insufficient to improve an organization’s

productivity (Herzberg, 1987). Organization leaders must maintain motivation factors to

ensure employee satisfaction. Lack of hygiene and motivator factors can increase

dissatisfaction; however, motivator factors do not increase dissatisfaction but can

increase and decrease satisfaction.

It is assumed that performance results are more likely associated with motivator

and hygiene factors to maintain performance levels. Those with higher motivator factors

and more satisfaction are more likely to overperform and go above and beyond their job

duties (Azevedo et al., 2020; Barden, 2017). On the other hand, those with higher

hygiene factors are less dissatisfied with their job and will likely perform at a basic

maintenance level. Although still satisfactory, these employees develop fewer innovative

strategies and tend to generate less output (Bevins, 2018). Furthermore, dissatisfaction

psychologically leads employees to withdraw from business operations (Herzberg, 1959).

This reasoning is why the Herzberg theory is considered a motivation theory, as Herzberg

found a statistical relationship between performance effects and satisfaction (Bevins,

2018; Herzberg et al., 1959; Herzberg et al., 1979). To motivate employees to achieve

desired outcomes, business leaders must understand what factors drive their employees

(Baumeister, 2016; Copeland, 2020; Damiji et al., 2015).

16

Research Relative to Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

Herzberg’s two-factor theory is the basis for many research studies, and many

researchers have expanded on the theory. For example, Adil and Hamid (2019) used

Herzberg’s two factor theory to determine if there is a direct relationship between leader

expectations of creativity and performance and if intrinsic motivators affect the

relationship between leader expectations of creativity and performance. The

componential theory of creativity describes three components of employee creativity:

expertise, creative thinking, and intrinsic motivation (Adil & Hamid, 2019). This

componential theory of creativity was expanded in 2016 (Amabile & Pratt, 2016) to

include boundary conditions such as work orientation, meaningful work, and effect.

These conditions affect the individual, the team, and organizational creativity and

innovation (Adil & Hamid, 2019; Amabile & Pratt, 2016).

Empirical evidence suggests that intrinsic motivation is a mediator between

different variables and creative performance (Adil & Hamid, 2019; Hannam & Narayan,

2015; Hur et al., 2016; Muñoz-Pascual, & Galende, 2017). Expectations from leadership

to perform creatively could serve as a motivator for an employee; however, if an

employee feels that they cannot perform creatively or innovatively, they are more likely

not to perform may become more dissatisfied (Adil & Hamid, 2019). If employees felt

that policy or their supervisor allowed for creativity, they would be less dissatisfied and

willing to increase their output (Adil & Hamid, 2019; PPS, 2019). Furthermore, if the

employee is motivated, they are more likely to grow, develop, and improve their

performance (Adil & Hamid, 2019; State of the American Workplace, 2020). It is

17

important to note that although hygiene factors and motivation factors influence job

satisfaction and dissatisfaction, the impact of each component of the factors varies

between employees (Thibodeaux et al., 2015).

Herzberg’s theory is also used to evaluate job satisfaction. Shaikh et al. (2019)

conducted a study to determine the impact of job dissatisfaction on extrinsic factors and

employee performance in the textile industry. The results showed that performance

increased when leaders focused on employees’ satisfaction and implemented relevant

hygiene factors to decrease dissatisfaction. However, though hygiene factors decrease

dissatisfaction, they have no impact on satisfaction (Shaikh et al., 2019). Regardless, to

maintain positive attitudes in the workplace, leaders should focus on improving motivator

factors such as recognition, the possibility for growth, and advancement. These factors

help improve performance and increase employee engagement and job satisfaction

(Amiri et al., 2017; Calecas, 2019; Herzberg, 1959). For example, employee feedback

can help employees to understand their roles better. Additionally, feedback can inform

employees about their performance and allows employers to recognize employees’

accomplishments (Aye, 2019; Herzberg, 1959; Rahman & Iqbal, 2013). These strategies

will help leaders increase morale, create happier and more satisfied employees, and

increase employee performance, increasing overall productivity.

Herzberg’s theory has since been expanded and still serves as the basis for many

other researchers. The theory has been applied in various industries, including human

resources, retail, and academia. The theory still receives criticism for lacking substantial

influence in explaining motivation. Other researchers have also argued that one of the

18

hygiene factors was misclassified and is a motivator, with only work itself having a

significant impact on job satisfaction (Onen & Maicibi, 2004; Smerek & Peterson, 2007;

Yousaf, 2020). But research has also shown that each motivator factor (e.g, relationship

with supervisors, work itself) positively correlates with job satisfaction (Yousaf, 2020).

The amount of recognition an employee gets also affects satisfaction. Employees who

receive more recognition are more satisfied and find their jobs more challenging and

rewarding than those who receive less recognition. Recognition is essential in motivating

employees, contributing to increased satisfaction and performance (Lehtinen, 2018).

Literature often discusses the performance of those being recognized but not that of those

not receiving recognition. Those who do receive recognition increased their performance

to maintain or continue to receive recognition (Yusaf, 2020). Thus, recognition increases

employee motivation and performance (Bradler et al., 2016; Gupta & Tayal, 2013;

Herzberg, 1959; Lehtinen, 2018).

Kahn’s Engagement Theory

The degree to which individuals immerse themselves in their work role relates to

their level of personal engagement or disengagement. Kahn’s engagement theory premise

is that people use varying degrees of themselves, physically, cognitively, and emotionally

in the workplace (Ali et al., 2019; Gupta & Sharma, 2016; Kahn, 1990). When Kahn

began developing this theory, existing research primarily focused on engagement driven

by job involvement, organizational commitment, and self-estrangement. Kahn (1990)

conducted a study to understand the conditions contributing to employee engagement in

the workplace. Kahn interviewed 32 employees to explore how certain job variables

19

affected employee engagement and analyzed the data using Grounded Theory to

articulate the complexity of influences on engagement levels in particular performance

moments (Kahn,1990). Kahn completed two qualitative studies, including counselors

from a summer camp and members of an architecture firm. The purpose of this study was

to explore conditions that cause people to engage, disengage, withdraw, or defend

themselves. Kahn described these actions as self-in-role processes. Essentially, positions

that allow individuals to exercise their preferred skills and talents and have their work be

an expression of themselves result in employees bringing their energy in all three areas of

physical, cognitive, and emotional aspects (Albrecht et al., 2015; Arleth, 2019; Kahn,

1990)

An employee can be engaged psychologically in two dimensions: emotionally and

cognitively. Those who are emotionally engaged typically have good relationships with

their supervisors and peers. Cognitively engaged employees are aware of their mission

and role in their work environment (Barden, 2017; Kahn, 1990; Rothbard, 2001). The

effort an employee is willing to exert to meet their goals is the measure of the physical

aspect of employee engagement. Employees can experience engagement in any of these

dimensions at any time. The employee engagement theory states that meaningfulness,

safety, and availability, influence employee engagement levels (Kahn, 1990).

Employees determine meaningfulness based on their experiences with work

elements that create incentives or, in some cases, disincentives. When employees

experience meaningfulness, they are more likely to feel valued and worthwhile and give

to others and the work itself. Meaningfulness is influenced by task and role

20

characteristics and overall work interactions (Balkrushna et al., 2018; Risley, 2020; Tong

et al., 2019; Tracey et al., 2014). The goals of these tasks and roles should be clear and

should allow for autonomy and creativity (Ma et al., 2020). Essentially, employees are

looking to have their jobs meet their needs for survival and their psychological needs.

Nikolova and Cnossen (2020) found that competence, autonomy, and relatedness explain

approximately 60% of the variation in work meaningfulness perception.

On the other hand, factors related to compensation are relatively unimportant

(Nikolova & Cnossen, 2020; Terkel, 1997). Employees that have meaning in their work

find value in more than just their paycheck. Kahn (1990) defines meaningfulness as a

return on investment, and employees are looking for more than just a paycheck.

Approximately one in two employees report that their jobs lack meaning and they feel

disconnected from their company's mission. Being detached is a sign of personal

disengagement.

Employee perspective on meaningfulness can predict absenteeism, skills training,

retirement intentions, and employee turnover (Bhatt&Sharma;2019; Byrne et al., 2017;

Nikolova & Cnossen, 2020; Paulo da Silva & Shinyashiki, 2014). A 2017 study

conducted by BetterUp, Inc. that included 2,285 United States residents revealed that

approximately nine of 10 employees would be willing to trade an average of 23% of their

lifetime earnings for greater meaning at work (Reece et al., 2018). Additionally,

employees who experience higher levels of meaningfulness at work tend to take fewer

leave days, work approximately an additional hour per week, and are 69% less likely to

leave their jobs within the next six months (Reece et al., 2018). When employees feel

21

they are receiving a return on investment, they are more likely to offer their resources and

perform effectively in their role. Employees with higher engagement are more likely to

provide additional time and dedication, share ideas willingly, and utilize creativity to

stimulate innovation.

For employees to experience safety in the workplace, they must have a sense of

ability to show and employ themselves without fear of negative consequences to their

self-image, status, or career. The influencers of safety are interpersonal relationships,

group, intergroup dynamics, management style and process, and organizational norms

(Kahn, 1990). A safe environment fosters support and trust and allows employees to learn

and improve their performance without fearing negative consequences. Increased levels

of trust also increase the amount of influence that leaders have. The management style in

this environment is supportive and resilient and provides clarity and consistency (Arleth,

2019; Gruman & Saks, 2010; Kahn, 1990; Lee & Huang, 2018). Leaders allow

employees to have some control over their work while providing reinforcement.

Employees' autonomy plays a significant role in fueling intrinsic motivation. A

lack of sense of safety can result from a manager not allowing an employee to have any

control over their work (Probst et al., 2020). An environment that does not promote

employee autonomy can make employees feel that their leadership does not trust them,

causing anxiety and frustration (Kahn, 1990; Kwon & Park, 2019). An employee must be

in an environment where critical thinking is openly exercised to have a sense of

psychological safety. Promoting openness in the work environment is also pivotal for

22

knowledge sharing, a crucial element in an organization's survival (Naujokaitien et al.,

2015).

Without the feeling of safety, employees are less likely to contribute their ideas,

beliefs, and values (Hyde, 2017; Snell et al., 2015). An environment that does not

promote a safe environment can contribute to inconsistency, unpredictability, and a

threatening environment that negatively impacts employee engagement. Researchers

argue that variables such as a leader's behavior influence motivation and can promote or

inhibit voluntary employee behavior (Parker et al., 2010; Qian et al., 2020). Employees'

willingness to improve their skills or performance can decrease for fear of negative

consequences due to a lack of perceived safety (Wang, 2021). The notion that employees

refrain from improving their skills is supported by research conducted by Qian et al.

(2020). Qian et al. found that levels of perceived safety impact the psychological

availability of employees.

Psychological availability is experienced when employees have physical,

emotional, or psychological resources to engage at a particular moment personally (Kahn,

1990) and apply to work and non-work experiences. Physical energy, emotional energy,

individual insecurity, and issues in personal life all impact psychological availability.

Insecurity impacts an employee's willingness to fully harness themselves in their role and

can create anxiety and diminish confidence. When employees are physically and

emotionally drained, they are likely to become disengaged, even if only for a moment,

decreasing their psychological availability (Ali et al., 2019; Bergdahl; 2020; Cao & Chen,

2019; Kahn, 1990; Kwan & Park, 2019).

23

Availability is driven by an employee's degree of confidence in their roles.

Organizational awareness of employee morale and training and development can be

supported by organizational awareness and the ability to create a work environment that

promotes positive social interaction (Bergdahl, 2020; Lee & Huang, 2018). Creating an

open environment can help alleviate the negative influencers and positively affect

employees' psychological states (Qin, 2020). Organizations have implemented dedicated

quiet rooms, Employee Assistance Program (EAP) access, stress retreats, resilience

training, and other resources to help employees alleviate tensions and help improve

employee mental health. The abovementioned strategies help employees accumulate,

manage, and reinforce positive beliefs about their physical, emotional, and cognitive

resources and enhance their psychological availability. Having availability can help

employees to accomplish extra tasks and requirements. Employees with psychological

availability have the physical energy and resources to help others in the organization and

cognitive resources to help generate new ideas (Fletcher, 2019; Kahn, 1990; Kultalahti &

Viitala, 2014; Nikolova et al., 2020; Smit et al., 2016; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2020),

creating a more efficient work environment (Naujokaitien et al., 2015). A more efficient

environment conducive to psychological meaningfulness, availability, and safety may

positively influence an employee's workplace engagement level.

When employees are engaged, they are more involved and invested in their jobs

and more expressive in the workplace. Alternatively, when employees withdraw from

their duties and disconnect and insulate themselves cognitively, physically, and

emotionally from their work roles, they become more disengaged (Hyde, 2017; Kahn,

24

1990). Engagement levels are a critical factor in employees' investment in their work

roles. Employees' energy contributes to engagement, and when engagement is present,

employees tie themselves to their roles freely without giving up their beliefs and values.

However, when employees are disengaged, they create barriers to their self-preservation.

It is important to note that Kahn (1990) suggests that people can move anywhere along

the spectrum of engagement and disengagement daily. Furthermore, where people fall on

the spectrum can also be influenced by work tasks, not just the job environment, as

previous research indicates (Kahn, 1990).

Some employees may ultimately enjoy their work environment and are engaged

when completing their day-to-day tasks; however, there may be an instance where an

employee has to complete an outside task. Being assigned that external task can influence

an employee's level of engagement, either positively or negatively (Kahn, 1990). For

example, if the employee is instructed to complete a task or role that makes them feel

important, they may become more engaged (Balkrushna et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2019).

Alternatively, if the role or task is perceived as unimportant and the employee sees no

value, the employee may disengage (Balkrushna et al., 2018). Employees are personally

engaged when they have the opportunity to express their best self within their role in an

optimal work environment without any emotional, cognitive, or physical sacrifice (Kahn,

1990; Balkrushna et al., 2018; Tong et al., 2019).

Kahn (1990) emphasized the different impact variables can have on people's

placement on the spectrum and went as far as to describe each moment as a contract

between person and role (Arleth, 2019; Handayani et al., 2017; Kahn, 1990). Employee

25

engagement is often viewed in its totality; however, Kahn's theory suggests that

engagement can be a summation of individual events. Having the understanding that the

events can be isolated allowed Kahn to analyze separate events in his study to determine

which variables impacted employee engagement.

Research Relative to Kahn’s Engagement Theory

Each year the federal government administers the FEVS, which measures

conditions conducive to engagement using the EEI as a metric. This metric includes 15

questions focusing on leaders leading, supervisor relationships, and intrinsic work

experiences for employees (OPM, 2019). The National Aeronautics and Space

Administration (NASA) was ranked number one as the best place to work in the federal

government by the Partnership for Public Service (PPS). NASA had the highest

employee engagement score of 81.5% (OPM, 2019; Partnership for Public Service [PPS],

2019). A study conducted by PPS (2019) found that employees at agencies with increased

engagement agree that they are allowed to improve their skills, encouraged to come up

with new ways to complete tasks, and feel their work is essential (Partnership for Public

Service [PPS], 2019). In addition, NASA employees rated the questions included in the

FEVS that relate to trust, improving skills, recognition, and innovation much higher than

other agencies, especially those with lower EEI scores (OPM, 2019), which further

supports Kahn's (1990) influencers of engagement. Another study by the PPS compared

employee engagement rates in the private sector against those in the public sector.

Understanding how the public sector compares to the private sector in employee

engagement is essential. The public sector must compete with the private sector to recruit

26

and retain high-performing employees. The PPS administered a 29-question survey

comprised of questions included in the FEVS issued to private-sector employees. This

study showed that the federal government fell behind the private sector in nearly every

question (PPS, 2019). The most significant gap was a 30-point gap on the issue of

employee voice. Eighty-two percent of private-sector employees reported trust in their

leadership instead of only 71% of federal employees (PPS, 2019). Another area in that

federal employees are rated lower than private-sector employees is awards and

recognition. Approximately 51% of federal employees feel they receive recognition for

their high-quality work, and only 45% believe that awards are given based on how well

they perform their jobs (OPM, 2019; PPS, 2019). The ratings for these items in the

private sector were 51% and 67%, respectively. Other lower-ranking areas for federal

employees are related training, supervisor support for development, and the ability to

develop innovative ideas. These issues resulted in a gap between seven and 17 points

(PPS, 2019). The overall engagement score for the Federal Government in 2019 is 61.7,

whereas the score for the private sector is 77 (PPS, 2019).

The PPS (2019) study findings suggest that trust within the organization, having

the opportunity to improve skills, receiving recognition, and having a safe environment to

foster innovation relate to increased engagement. These concepts support Kahn’s

engagement theory as it supports the notion that meaningfulness, safety, and availability

impact levels of employee engagement (Arleth, 2019; Gruman & Saks, 2011; Kahn,

1990; Osborne & Hammoud, 2017). Kahn (1990) defines meaningfulness as a sense of

return on investment on self-in-role performance. Tasks, roles, and work interactions are

27

all influencers of meaningfulness (Gruman & Saks, 2011; Kahn, 1990). Tasks should

have some level of challenge and allow for autonomy and creativity. Employees also

experience meaningfulness when they feel worthwhile and valued (Kahn, 1990; Osborne

& Hammoud, 2017; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2020). Federal employees had lower

ranking scores than the public sector regarding questions concerning innovation and

employee voice. Federal employees also felt undervalued, as 49% of the federal

employees who participated in the FEVS (2019) did not feel recognized for their quality

work. The results show a negative impact on meaningfulness felt by the federal

employees, which could contribute to the lower engagement rating. The scores were

higher in the private sector, ultimately contributing to the higher engagement rating (PPS,

2019).

The findings of PPS (2019) suggest a lack of safety in the federal employee work

environment. Safety relates to trust, openness, flexibility, and lack of threat in the

workplace (Kahn, 1990). Employees feel safe when leaders are supportive, consistent,

and trustworthy (Feuerahn, 2019; Funez et al., 2021; Morton et al., 2019). Fewer federal

employees expressed trust in their leadership than in the private sector (PPS, 2019). The

private sector employees rated this area 11 percentage points higher than the federal

employees (PPS, 2019). The third factor is availability, which relates to emotional,

physical, and psychological resources (Kahn, 1990). Training was rated lower and

received less support by leadership in the federal workplace (PPS, 2019), an example of a

lack of physical resources. Finally, insecurity is also an influencer of the availability

factor. Lack of training or support for professional development can contribute to

28

employees being insecure in their skills and capabilities (Funez et al., 2021; Lee &

Huang, 2018; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2020). Suppose the employees feel they are not

provided enough resources to do their job adequately or that their leadership did not

support their development. In that case, they are likely to refrain from sharing innovative

ideas, hiding how they feel, and becoming less secure in their overall performance.

Ultimately, the three areas that impact engagement were rated lower by the federal

employees, potentially contributing to the overall lower engagement score.

Researchers have continued to use and expand upon Kahn's (1990) engagement

theory. For example, Nguyen et al. (2018) conducted a study to examine the relationships

between job engagement, transformational leadership, high-performance human resource

practices (HPHRP), climate for innovation, and contextual performance. The researchers

were looking to investigate what variables generate engagement and how the levels of

engagement improve contextual performance in higher education. Engagement, in this

study, is described as an enduring state of mind that refers to an employee's investment of

physical, cognitive, and emotional energies. Thus, the definition of engagement in this

study aligns with Kahn's definition of engagement.

Understanding how engagement influences organizational and employee

performance and knowing what variables influence engagement can help organizations

create more conducive environments to meet the needs of their employees and the

organization. Nguyen et al. (2018) gathered the data for their study by sending an online

and paper-based questionnaire to 14 public and private universities in Ho Chi Minh City,

Vietnam, in 2016 (Nguyen et al., 2018). The data for both the dependent and independent

29

variables were collected from two sources, university academics, and their leaders, in two

different phases. During the first phase, the academic staff completed a questionnaire

regarding the transformational leadership styles of their leaders, job engagement, and

HPHRP. During the second phase, the same team completed another questionnaire

relating to their school's climate for innovation. The staff leaders were also surveyed in

this phase, and their questionnaire addressed the organizational citizenship behavior

(OCB) and the innovative work behavior of their staff. The researchers created a data file

by matching the responses of demographics, transformational leadership, HPHRP,

climate for innovation, and job engagement ratings by the staff during phase one and

phase two, and the responses by leadership on OCB and innovative work behavior using

assigned codes.

The framework for Nguyen et al.'s (2018) study is based on Kahn's (1990)

engagement theory and social exchange theory to create a conceptual model that

demonstrated a relationship between job engagement and transformational leadership,

HPHRP, climate for innovation, OCB, and innovative work behavior. The findings

suggest that transformational leadership and HPHRP are critical drivers of employee

engagement levels, HPHRP having more influence than transformational leadership.

HPHRP consists of selection, training and development, job security, promotion,

performance-related pay, autonomy, and communication. Transformational leadership

includes idealized influence, inspirational motivation, individualized consideration, and

intellectual stimulation (Nguyen et al., 2018). The significant and positive relationship

between these variables and employee engagement supports Kahn's engagement theory.

30

HPHRP encompasses concepts influencing psychological meaningfulness, such as skill

development, performance recognition, and autonomy. When employees experience

meaningfulness, in this case through HPHRP, they feel useful and valuable.

Transformational leadership relates to safety concepts (Lee & Huang, 2018). Safety

provides an environment where employees can try and fail without fear of consequence,

have supportive and trusting leadership with significant influence, and create and test

new ideas and concepts (Kahn, 1990; Lee & Huang, 2018).

Creating an innovative climate can influence engagement (Funez et al., 2021;

Kahn, 1990). Leaders who want success within their organizations must develop

strategies to attain engaged employees (George & Joseph, 2014; Ghlichlee & Bayat,

2020; Kwon & Park, 2019). Employee engagement is fostered by a fulfilling experience

that accounts for vigor, dedication, and absorption (Kim et al., 2016; Schaufeli et al.,

2002). Ultimately, the study's findings by Nguyen et al. (2018) supported Kahn's (1990)

engagement theory by identifying a positive relationship between the influencers,

variables, and engagement. Furthermore, Nguyen et al. (2018) found that when

engagement was present, employees were more willing to be involved in additional tasks

outside their work tasks, complete tasks more effectively, and try more innovative

approaches, contributing to increased OCB (Morton et al.,2019).

Implications of Kahn’s Engagement Theory

Employees need to be able to express themselves and have a sense of autonomy in

their work lives (Lee & Huang, 2018). Employees' psychological experience in the

workplace drives their attitudes and behavior, ultimately impacting their involvement in

31

their roles. The lack of meaningfulness, safety, and availability can lead to personal

disengagement, causing employee burnout and robotic performance (Kahn, 1990;

Upadyaya & Aro, 2019). Employees become unexpressive and refrain from sharing

thoughts and creativity instead of being innovative when experiencing burnout (Kahn,

1990; Kwon & Park, 2019; Upadyaya & Aro, 2019).

Organization leaders should be more cognizant of the effects of burnout on

employees and their performance. Upadyaya and Aro (2019) conducted a study to

determine what types of groups of employees can be identified according to the level of

burnout, which consists of changes in their exhaustion, cynicism, feelings of inadequacy,

and levels of engagement, consisting of energy, dedication, and absorption. The

researchers also explored how work-related demands and resources and personal-related

demands and resources predict employees belonging to the burnout or engagement

profiles. Seven hundred sixty-six employees participated in this study, filling out a

questionnaire concerning their burnout symptoms, work engagement, perceived demands

and resources, and occupational health. The participants were surveyed twice. The results

were analyzed in multiple phases. First, the results were assessed and grouped based on

similar indicator means, burnout and engagement. Subsequent different work-related

demands and personal demands and work-related resources and personal resources were

added as covariates. The first group, 84% of the participants, were characterized by an

average level of burnout and high engagement, which slightly increased over time. The

second group represented 16% of the participants and was characterized by high levels of

burnout that grew over time and an average level of engagement that decreased over

32

time. Employees who experienced high work-related and personal resources, such as

servant leadership, resilience, and self-efficacy, were likelier to belong to the high

engagement group. Employees who experienced high work-related and personal

demands, such as project and relationship demands, were more likely to belong to the

increasing burnout group.

Organizational leaders need to understand the impact of burnout and the

importance of a workplace conducive to decreasing burnout. The results of Upadyaya and

Aro's (2019) study suggest that employees were experiencing increasing levels of

exhaustion, cynicism, and feelings of inadequacy and experiencing decreasing levels of

energy, dedication, and absorption. Creating a work environment where employees have

adequate resources and support to meet work demands can positively impact employee

engagement and the effort they put into their work (Ghlichlee & Bayat, 2020; Seriki et

al., 2020; Upadyaya & Aro, 2019).

Suppose employees believe their organization invests in them and provides the

necessary resources to create an optimal workspace. In that case, employees are more

likely to offer their resources and exhibit more effort, becoming more cognitively alert,

emotionally attached, and physically involved (Concepcion, 2020; Lee & Huang, 2018;

Kahn, 1990; Upadyaya & Aro, 2019). These three attributes represent a fully harnessed

employee, and when all are applied, employees tend to be more productive and efficient

(Kahn, 1990). Therefore, if leaders focused on creating a work environment that

minimizes the negative impact on the cognitive, physical, and emotional engagement

33

attributes, they could foster employee engagement and inspire more positive productivity

(Anithat, 2014; Kahn, 1990; Lin & Hsiao, 2014; Rana et a., 2014).

Alternate Theories

Although Herzberg's theory and Kahn’s engagement theory are used in the

theoretical framework for this study, it is essential to note that similar theories explore

job satisfaction and employee engagement. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory and SDT

are two popular theories of motivation. Both of these theories are alternate theories to

Herzberg’s two-factor theory. In this section, I will present these theories and provide an

analysis of each. Additionally, I analyze Job Demands-Resources Theory in this section

as this is an alternate theory to Kahn’s engagement theory.

Maslow’s Hierarchal Theory

Maslow (1943) introduced a motivation theory known as the Hierarchy of needs

theory. In his theory, Maslow suggests five basic needs: physiological needs, safety,

social, self-esteem, and growth needs, also known as self-actualization. The hierarchy of

these goals is in a pyramid shape, with physiological needs at the base as the basic needs.

The pyramid also depicts the importance of some needs over others, showing how the

order of satisfaction influences motivation. Physiological needs refer to one's most basic

needs, such as thirst, air, and food (Gawel, 1996; Maslow, 1943). Staying safe from

physical and psychological harm, security, stability, and protection are related to safety

needs. The social need implies the need to feel a sense of belonging, esteem focuses on

respecting self and others, and self-actualization is the need to reach one's maximum

potential. Maslow's theory suggests that the goals are all related and range in a hierarchy

34

of prepotency, meaning before the higher-level needs can be met, the lower-level needs

must first be met. When a lower-level need is met, motivation for satisfying that need

decreases, and people will try to meet the needs of the next level (Gawel, 1996; Maslow,

1943; Stefan et al., 2020; Suyono & Mudjanarko, 2017).

Maslow's (1943) theory offers a practical theory of management for organizations

and a psychological and social theory that explains changing social values and needs. In

response to this, organizations that utilized Maslow's theory made efforts to make work

more meaningful and fulfilling (Lusier, 2019). However, Maslow's theory has faced

criticisms for not being supported by empirical data, assuming that employees are

comparable, prioritizing the needs of the worker, and discounting employees' ability to

achieve higher-order needs before lower-order needs (Graham & Messner, 1998; Kaur,

2013; Lusier, 2019; Stefan et al., 2020).

It is challenging to standardize organizational hierarchy goals as the needs differ

from person to person based on multiple factors. A study by Lussier (2019) found that the

assumption that employees are comparable proved to be a detriment of Maslow's theory

as it neglected inequalities and poverty in the minds of organizations. Additionally,

research has shown that motivation levels are higher when the higher-level needs are met

(Deci & Ryan, 2014; Stefan et al., 2020). If leaders want to increase motivation in their

organizations, they should focus on improving the higher-level needs.

Herzberg's Two-factor theory and Maslow's Hierarchy of needs theory are similar