Working Papers

Paper 94, July 2014

The effects of

independence, state

formation and migration

policies on Guyanese

migration

Simona Vezzoli

DEMIG project paper 20

The research leading to these results is part of the

DEMIG project and has received funding from the

European Research Council under the European

Community’s Seventh Framework Programme

(FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement 240940.

www.migrationdeterminants.eu

This paper is published by the International Migration Institute (IMI), Oxford Department of International Development

(QEH), University of Oxford, 3 Mansfield Road, Oxford OX1 3TB, UK (www.imi.ox.ac.uk). IMI does not have an institutional

view and does not aim to present one. The views expressed in this document are those of its independent authors.

The IMI Working Papers Series

The International Migration Institute (IMI) has been publishing working papers since its foundation in

2006. The series presents current research in the field of international migration. The papers in this

series:

analyse migration as part of broader global change

contribute to new theoretical approaches

advance understanding of the multi-level forces driving migration

Abstract

Using a historical approach, this paper examines the evolution of Guyanese migration from the 1950s

until the 2010s. It explores the role of the Guyanese state in migration, the effect of independence and

the establishment of a border regime on migration, with a particular focus on how political decisions

and socio-economic policies have affected the timing, volume, composition and direction of migration

in the post-independence period. After elaborating a new conceptual framework, the paper analyses the

role of the Guyanese state across three broad historical phases: from the early 1950s to independence

in 1966; from independence to the gradual political and economic opening of Guyana in 1985; and from

1986 to the present. The paper finds that the uncertainties generated by Britain’s introduction of its

Immigration Act in 1962 and Guyana’s independence in 1966 led to two initial increases in emigration

in the 1961-1962 and in 1965-66 periods. The Guyanese state’s support of 'cooperative socialism' and

its authoritarian stance until the mid-1980s then promoted large emigration, which gradually included

all classes and ethnic groups. At the same time, British and North American migration policies cause

the partial redirection of migration towards the US and Canada. The importance of family re-unification

and skilled migration channels explain on one hand, how entire Guyanese families have emigrated,

while on the other hand, how Guyana is one of the top ten countries for skilled migrants. This paper

shows the importance of shifting beyond the ‘receiving country’ bias by considering the important role

of origin country states in migration processes.

Author: Simona Vezzoli, International Migration Institute, University of Oxford,

simona.vezz[email protected]

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 3

Contents

1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 4

2 Border regimes, post-colonial ties and migration substitution effects: A conceptual

exploration .................................................................................................................. 5

2.1 Synchronic independence and border regime establishment .............................................................. 6

2.2 Asynchronous independence and border regime establishment ........................................................ 8

2.3 State formation and migration .................................................................................................................... 9

3 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 10

4 Setting the scene: British Guiana’s historical migrations and ethnic diversity .......... 11

5 1953-1965: The long road to independence and the closure of the British border . 12

5.1 Political transitions and the effects of the 1962 British Immigration Act .................................... 12

5.2 The opening of North American migration policies ............................................................................. 14

5.3 Independence and the weakening of migration to Britain ................................................................ 15

6 1966-1985: ‘Co-operative socialism’, authoritarianism and emigration growth .... 17

6.1 The unintended migration stimuli of socio-economic reforms ........................................................ 17

6.2 Widening authoritarianism and population movement control ........................................................ 18

6.3 Corruption, discrimination and the emigration of skilled workers .................................................. 19

6.4 Continual transition to North American destinations ......................................................................... 20

6.5 The diversification of emigration ............................................................................................................. 21

7 1986-2013: Persistent instability and the consolidation of migration patterns ..... 22

7.1 Strenuous ethnic relations and a stammering economy .................................................................... 22

7.2 The selectivity of North American migration policies ......................................................................... 24

7.3 Long-term emigration effects of national constraints and migration policies ............................ 26

8 Insights on the relevance of the state and its policies on international migration .... 29

References ................................................................................................................ 31

4 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

1 Introduction

After a gradual process of decolonisation beginning in the early 1950s, British Guiana obtained

independence in 1966 when it became the independent state of Guyana. The political, social and

economic transformations triggered by independence significantly affected the living and working

conditions in the newly independent country, and altered historical migration patterns to and from

Guyana. No systematic empirical research has been conducted on how processes of decolonisation and

independence shape migration, whether their effect is long-term, or how other developments during

state formation influence migration patterns. This paper adopts a state perspective to examine the

relation between the state and migration processes and seeks to answer the questions: How do states

and their policies contribute to shaping the volume, timing, direction and composition of migration?

And more specifically, how do the process of decolonisation and post-independence state formation

affect migration patterns? This paper adopts a historical approach to present an analysis of processes of

political and socio-economic change and examine how they may have affected migration patterns to

and from Guyana from the 1950s until today.

Guyana has historically had a small population. With 560,000 inhabitants in 1960, its emigrant

population was 6 percent of the total population, lower than many Caribbean countries. Migration has

drastically increased since the mid-1970s, and today Guyana has one of the highest percentages of

emigrant population in the world – an estimated 56 percent in 2010.

1

Guyana’s staggering emigration

figures suggest that independence may have ignited emigration, which was further stimulated by post-

colonial ties and reinforced by the cumulative effects of migrant networks. A closer look at Guyanese

migration trends reveal that the developments that unfolded within Guyana over the past sixty years in

conjunction with migration policies in the major destination countries have greatly influenced migration

patterns.

This paper aims to explain how political, social and economic changes have contributed to

shifts in the volume, timing, destination and composition of Guyanese migration. The paper analyses

the role of the state across three broad historical phases: from the early 1950s to independence in 1966;

from independence to the gradual political and economic opening of Guyana under President Hoyte’s

government in 1985; and from 1986 to the present. For each phase, I examine the actions of the state,

its ideology, and migration as well as other policies, to identify events or processes that have affected

migration. Immigration policies of major destination countries are also part of this analysis.

The state is a central agent of development, able to create institutions and infrastructure that

facilitate economic and social development and provide or inhibit individuals’ opportunities, hence

producing significant migration effects (Skeldon 1997). Its role seems even more relevant in the

decolonisation and post-independence period, when the governments of newly independent states

generally introduced ambitious development plans to set the country on a new course. States also often

wish to control population movements in response to demographic, economic or social conditions.

Thus, the state is taken as a point of departure to examine the conditions it creates on the ground, with

the understanding that these conditions affect the sets of opportunities and challenges faced by

individuals and influence their migration decisions. A state-centred approach may be problematic for

1

Source: World Bank Global Bilateral Migration Database, http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/global-

bilateral-migration-database; 2010 Estimates,

http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTDEC/EXTDECPROSPECTS/0,,contentMDK:22803131

~pagePK:64165401~piPK:64165026~theSitePK:476883,00.html, accessed on August 25, 2013.

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 5

two reasons: first the state is not a monolith but an ensemble of actors with specific and contradicting

interests; and second, this approach inherently emphasises structural elements, ignoring individuals’

agency. I attempt to diminish these shortcomings by consulting various government documents,

speaking with various country experts and including qualitative interviews with individuals affected by

migration.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a conceptual exploration of potential

migration consequences of decolonisation and post-independence state formation processes and it

defines independence, border regimes and post-colonial ties and their hypothesised migration effect.

After a brief methodological description in section 3, I introduce British Guiana’s historical migrations

in section 4. Sections 5 to 7 present three broad historical periods, which capture political, economic

and social transitions that underlie the major shifts in Guyanese migration patterns: from the 1950s to

1965; from independence in 1966 to 1985; and from 1986 to today. Finally, section 8 analyses the

evolution of Guyanese migration timing, its volumes, direction and composition and concludes with

insights of how the state and its policies shape migration patterns in direct and indirect ways.

2 Border regimes, post-colonial ties and migration substitution

effects: A conceptual exploration

Starting in the 1960s, the literature on Caribbean migrations acknowledged that the transition from

colony to independent country produced changes, with a particular focus on the introduction of

immigration policies and their migration consequences. Empirical evidence shows that West Indian

migration to Britain was altered by the introduction of the British Immigration Act of 1962 in

conjunction with the opening of immigration policies in North America, but also identified an important

shift in employment opportunities from Britain to North America (Marshall 1987; Nicholson 1985;

Palmer 1974; Peach 1995). In his seminal work on West Indian migration to Britain, Peach (1968)

stressed how the 1962 Immigration Act, which was the first official constraint to immigration for West

Indians and other Commonwealth citizens, created a ‘beat the ban’ migration rush. He also emphasised

that the employment opportunities in Britain had been important determinants, while origin country

factors were merely ‘enablers’ and ‘passive’ factors in migration processes. Research in the 1960s and

1970s played a vital role in challenging the contemporary bias that linked immigration to Europe and

North America solely on underdevelopment, high unemployment and population pressure in Caribbean

countries, while ignoring the labour demand and migration policy factors in destination countries.

While valid, this shift may have obfuscated the migration effects of the structural changes

triggered by the transition to independence. In fact, over the years, the opposite bias developed as

research focused almost exclusively on destination country factors, including immigration policies (cf.

de Haas 2011). Gradually researchers are rediscovering origin country factors, such as historical

connections (e.g. colonialism, language and institutional similarities), geographical conditions (e.g.

landlocked, proximity) and specific indicators such as investment in education and welfare services

(Beine, Docquier and Schiff 2008; Bellemare 2010; Belot and Hatton 2010; Kim and Cohen 2010;

Kureková 2011). Little conceptualisation has occurred however, not only of how a broad range of

migration determinants (e.g. education, protection of private property, promotion of specific economic

sectors and infrastructural development) are located in the origin country, but in fact that they are shaped

by the origin state. Yet, origin states are hardly considered and they are perceived as powerless, even

though in reality they are often concerned with population movement and engage with migration

policies (cf. de Haas and Vezzoli 2011) as well as other policies that may indirectly shape migration.

6 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

When we take a broader perspective of the state, it becomes apparent that the role of the origin state in

migration has been greatly underexplored.

This paper explores the role of the origin state in migration processes by examining Guyanese

migration from the 1950s to the 2010s through Guyana’s deep structural changes, starting with

decolonisation leading to independence and the formation of an independent state. Two factors stand

out during the transition to independence that may explain migration dynamics: the establishment of

border regimes and post-colonial ties. Moreover, this transition involved changes to several state-led

aspects that may affect migration (e.g. institutions, bureaucratic functions, education and taxation

systems and migration policies). After presenting a conceptualisation of how the establishment of

border regimes, independence and post-colonial ties may influence migration patterns, this paper

explores how origin country state determinants may affect migration during the long-term processes of

state formation. I rely on hypothetical models as hermeneutic tools to examine how development

processes around independence may lead to variations of migration that go beyond its volume to

encompass its composition, timing and direction.

2.1 Synchronic independence and border regime establishment

The process of decolonisation generally culminates with independence, a point of political breakage

with the past that gives start to the formation of a new state. In fact, strong post-colonial relations may

continue after independence with the former colonial state retaining great influence on the policies

adopted by former colonies (e.g. Suriname)(de Bruijne 2001; Sedoc-Dahlberg 1990). It can also be

argued that decolonisation may result in other forms of non-sovereign governance such as incorporation

or departmentalisation (i.e. Puerto Rico and French Guiana). When decolonisation results in

independence, two migration-relevant structural changes take place: the establishment of national

borders, marking the official separation of previously continuous political units; and a new citizenship,

removing freedom of movement rights previously guaranteed to ‘colonial subjects’. These two changes

lead to the establishment of a border regime, namely a set of regulations designed to control movement,

which are implemented at the physical border and beyond (Langer 1999). A border regime generally

results in immediate constraints to the population’s freedom of movement and it may also produce

unintended ‘migration substitution effects’, namely the effects of migration policy restrictions on the

volume, timing, spatial orientation or composition of migration flows (de Haas 2011). Figure 1 visually

represents the potential migration consequences of independence, displaying expected inter-temporal,

categorical and spatial substitution effects.

In most circumstances, independence corresponds with a change in the set of opportunities and

challenges faced by the population. On one hand, independence may be experienced as a moment of

great opportunities, particularly for groups of citizens close to the power structure. On the other hand,

the transfer of power from a familiar colonial government to a newly independent government may

generate anxiety. In anticipation of the establishment of a border regime, residents may migrate pre-

emptively, primarily to the former colonial state, causing a spike in emigration right before and around

the year of independence (see Figure 1). This results in ‘now or never’ migration, also termed an inter-

temporal substitution effect (cf de Haas 2011), as previously observed by Peach (1968) a year before

the introduction of the 1962 UK Immigration Act.

The changes introduced by independence may however, influence more than migration

volumes. Diverse reactions among the population may lead to various propensities towards migration

along class, ethnic or political lines rather than a universal preference for emigration. Thus, the

composition of the population leaving pre-emptively is expected to reflect more heavily the segments

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 7

of the population that are most uncertain about the country’s future perspectives (e.g. groups without

political and economic connections or the political opposition) or who may fear a loss from being

prevented future entry into the former colonial state (e.g. job opportunities or family already at

destination). Thus, independence and border closure are likely to transform the composition of

migration flows.

Figure 1. The hypothesized effects of independence and the establishment of a border regime on

international migration, with substitution effects

After independence, migration may taper off, particularly if socio-economic conditions are

stable and feelings of uncertainty subside, although migration is likely to continue in the short-term into

the post-independence period. The migration policies implemented by the former colonial state and

other potential destinations may however, change the structure of migration and produce three

additional unintended migration substitution effects: categorical, spatial and reverse migration (de Haas

2011). Categorical substitution occurs when migrants rely on diverse types of channels, legal or illegal,

to emigrate. When entry channels are constrained, prospective migrants may explore family

reunification, study, asylum and any other migration channels that may grant them access. For example,

immigration to Britain over the 1965-1970 period showed that 72 to 86 percent of Commonwealth

citizens were entering as dependents using family reunification channels,

2

although spouses generally

worked once in Britain.

Post-colonial ties may also explain categorical substitution. Post-colonial ties have been loosely

defined as a number of social, cultural, linguistic, educational connections and privileged relations

between former colonial subjects and their former colonies, which make the former colonial state a

preferred migration destination (Beine, Docquier and Özden 2009; Belot and Hatton 2010; Constant

and Tien 2009; Fassmann and Munz 1992; Hooghe et al. 2008; Thielemann 2006). This notion assumes

2

Immigration Bill: Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Home Department, Cabinet, CP(70)126, 31

December 1970, The National Archives, Catalogue Reference: CAB/129/154

Emigration flows

Time

Independence and border regime

with former colonial state

Inter-temporal

substitution

effect

Spatial substitution effect (i.e.

emigration to destinations other than

the former colonial state)

Categorical substitution effect

(i.e. family reunification,

rather than labour)

8 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

that colonialism created a positive connection to the former colonial state and migrants universally

prefer the former colonial state regardless of migration constraints or past experiences in the ‘mother

country’ (Thomas-Hope 1980). High levels of restrictiveness of migration policies may however

prompt migration to the former colonial state through other channels (e.g. asylum, irregular) or possibly

to other destinations, leading to spatial substitution effects (de Haas 2011). By examining categorical

and spatial substitution effects, we can move towards a deeper understanding of when and how colonial

links shape international migration.

Hypothetically, emigration from newly independent states may experience an independence

peak followed by sustained but gradually decreasing migration as conditions stabilise in the newly

independent country and post-colonial ties gradually lose their importance, while migration to new

destinations may gain relative strength. Moreover, the imposition of restrictive immigration policies in

the former colonial state (e.g. limiting family reunification) may potentially cause step-wise migration,

namely the pursuit of a regular permanent immigrant status in a third country. Although not represented

in Figure 1, a fourth migration substitution effect may occur, namely the reduction of return flows as a

result of the stringent rules for re-entry in destination countries. From an origin country perspective,

this effect would potentially reduce the volume and alter the composition of return flows. Empirical

evidence shows that return is negatively affected by a temporary or irregular status, as individuals with

precarious visas may prefer to stay put even when return may be the preferred option because of the

risk of being unable to re-enter (Massey 2005).

2.2 Asynchronous independence and border regime establishment

It is often assumed that independence corresponds with the establishment of a border regime, but in

reality independence may occur before, at, or after the establishment of border regimes. Langer (1999)

points to the fact that political borders may exist without border regimes (e.g. EU). Just as border

regimes may exist without political borders. In the British Caribbean, only Jamaica and Trinidad and

Tobago obtained independence in 1962, within four months of the implementation of Britain’s

Immigration Act. The British citizens residing in other former British Caribbean colonies that gained

independence between 1966 and 1983 were unable to migrate to Britain in the years leading to

independence. Figure 2 illustrates how the pre-emptive establishment of a border regime may affect

migration outcomes. A third ideal-type model, applicable to the case of Suriname, presents the potential

migration substitution effects when border control measures are introduced after political independence

(Vezzoli 2014 forthcoming).

When border control anticipates independence, levels of uncertainty may be less acute at each

instance. Pre-emptive migration may occur before border closure; however, political continuity may

reduce the perceived risks associated with remaining in the colony and large parts of the population

may wait and see. The inter-temporal substitution effects would not be expected to be as high as in

Figure 1. However, the nearing of independence may prompt migration as a risk-reduction strategy.

The ‘now or never’ effect may be more pronounced in case of high instability paired with available

entry channels in the former colonial state, strong post-colonial ties or favourable migration policies in

alternative destinations. On the other hand, the lack of migration opportunities to the former colonial

state or alternative destinations, weak post-colonial ties, but also stability and positive future prospects

in the new independent country may produce a less pronounced emigration peak. It is unclear whether

the absolute volume of migration in Figures 1 and 2 would be the same, as the ‘wait and see’ attitude

may not necessarily preclude emigration at a later time. Migration policy constraints may however

hinder migration at later stages, reducing the total volume of migration in Figure 2.

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 9

Figure 2. The hypothesized international migration effects of the establishment of a border

regime followed by independence

In the period between border closure and independence, diversified migration patterns may

develop both in terms of the migration channels used (i.e. family channels and study rather than labour)

towards the former colonial state and also the gradual reliance on alternative destinations. In contrast to

Figure 1, by independence alternative destinations may be well-rooted, reducing the relevance of the

former colonial state in long-term migration flows. Under these conditions, the effect of post-colonial

ties may rapidly weaken.

The border regime-independence sequence may also alter the composition of migration flows.

Since not all members of society would have had free access to migration before the introduction of

migration restrictions due to low capabilities and connections to migrate, the flows may have been

overrepresented by the elite and the middle class with access to resources, connected with the colonial

government or pursuing higher education. Conversely, the second wave of emigrants may be composed

of individuals fearful of the changes induced by independence, although only those with access to

resources and useful connections may be able to migrate. Ultimately, independence and the

establishment of a border regime and their timing provide vital insights of the dynamism of migration

responses.

2.3 State formation and migration

State formation processes are crucial in determining long-term migration patterns. During the state

formation phase, the independent state introduces a number of reforms and policies promoting a new

national vision. Reforms may build on previous institutions and display continuity (e.g. economic

structure) or alternatively introduce discontinuity (e.g. educational system reform). Broad reforms are

expected to alter the opportunities available to the population at large or segments thereof. While the

attractiveness of destination countries or the increasingly large communities in destination countries

may strongly shape migration, the developments in the origin country may explain the rationale for

migration, its surge at specific points in time (e.g. before and after independence), its volume and

composition (e.g. politically- or ethnically-targeted groups) and its destination (e.g. post-colonial ties,

Emigration flows

Time

Border regime with

former colonial

state

Independence

First inter-

temporal

substitution

effect

Prolonged spatial and categorical substitution

effects (alternative destinations and migration

channels progressively utilised)

Second (weaker)

inter-temporal

substitution

effect

10 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

trade relations). This conceptual framework explores a combination of factors that emerged as

influential drivers of Guyanese migration and shows how their relative importance in shaping migration

has changed over time.

3 Methodology

This paper relies on scholarly articles, books and reports on the political and economic developments

and migration from and to Guyana; historical documents issued by colonial and Guyanese governments

reporting migration data and policy discussions; articles from 13 Guyanese newspapers between 1962

and 2013; and a limited number of historical articles from British newspapers.

3

These sources were

complemented with data from 30 interviews conducted in Guyana and Suriname between October 2013

and January 2014. The interviews explored individual migration trajectories, family migration, time and

duration of migration, and return. The purpose of the interviews was to: learn about migration decision

processes, including rationale, timing and destination; and investigate the relevance of structural

changes, e.g. independence and political changes, on individuals’ migration decision process. Among

the interviewees, 8 individuals were still abroad, 9 had returned to Guyana, and 13 never migrated from

Guyana, although they may have travelled abroad. In addition, one in-depth interview was conducted

with a government official who has held various positions in government since the 1970s and provided

valuable insights into government debates on migration.

The interviews do not aim to be representative of Guyanese society and do not pretend to

represent the full spectrum of migration from Guyana, in terms of its timing or composition.

Interviewees were however, selected to include a wide range of migration experiences at different points

in time, and different ethnic groups and social classes. The characteristics of the interviewees are as

follows: 19 men and 12 women; 12 Afro-Guyanese, 15 Indo-Guyanese and 4 individuals with a mixed

background; 17 are originally from a rural area and 13 from urban areas, mainly Georgetown; the

interviewees largely represented the low to medium class although the father of three interviewees had

a government job; and the age of interviewees ranged between 23 and 75. Through a chronological

analysis of the secondary literature, government documents and newspaper articles and the interviews

I was able to identify the emerging conditions and migration-related factors relevant in each period.

This proved to be an effective triangulation method as the interviews often substantiated and provided

insights on the dynamics that had been described in the primary and secondary literature. While

interviews about past events suffer from ex post justification of past behaviour to fit socially-accepted

models or ‘standard motivations’ (Menke 1983), interview techniques were adopted to ensure

coherence of personal stories and consistency with time-specific historical events and living conditions.

Thematic coding of the interviews allowed to emergence of insights on the fluctuating importance of

migration and its driving forces in the past and today. Moreover, the interviews raised my awareness of

migration as a life strategy which responded to changing living conditions in Guyana as interviewees

described life adaptation strategies in critical moments (e.g. food shortages, heightened violence),

migration strategies, complex histories of family migration and the diffusion of migration knowledge,

in terms of migration policies, migration policy loopholes and the advantages and disadvantages of

migration as a life experience.

3

Most articles from Guyanese newspapers are from the Guyana Chronicle and Stabroek News, while articles from

the British press are mainly from The Guardian.

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 11

4 Setting the scene: British Guiana’s historical migrations and

ethnic diversity

Within the British Empire, British Guiana was historically considered a colony of relatively low

economic and strategic importance, with sugarcane and rice as the main economic activities (Rabe 2005;

Standing 1977). Labour shortages were recurrent in this scarcely populated colony. Initially British

planters attempted to use local Amerindian populations for plantation work but these efforts were

unsuccessful (Baksh 1978). Therefore colonial authorities procured plantation labour through slavery,

but the abolition of slavery in 1834 generated labour demand. Initially, this was resolved through

introducing a four-year period of apprenticeship, but once freed slaves saw that poor conditions and

low wages persisted, they refused to continue working on the plantations (Baksh 1978).

Given the persistent labour demand, planters resorted to the recruitment of indentured labour

from India, which resulted in 240,000 East Indians entering British Guiana in the period between 1838

and 1917, the year in which this system was abolished (Peach 1968). Indentured workers also came

from the Madeira Islands and from Hong Kong, but the 25,000 Portuguese and Chinese indentured

workers quickly left the harsh conditions of the plantations and entered retail trade (Baksh 1978). While

East Indian workers had the right to return to India after their indenture contract, the majority remained

in the rural areas of British Guiana to work on sugar plantations (Rabe 2005). Until 1928, British

Guyanese planters continued to demand inexpensive labour and recruited workers in the Caribbean

islands, which remained the last source of labour after 1917 (Baksh 1978; Marshall 1987).

In the meantime, many former slaves had pooled together their resources to buy abandoned

sugar plantations and establish villages, where they could cultivate their own crops (Baksh 1978;

Nicholson 1976). Plantation owners opposed any agricultural development that may compete with the

plantation system and obstructed village productivity (Canterbury 2007). Over the years, the villages

proved unsustainable. Internal migrations took place as some villagers returned to work on plantations,

while many others migrated to mining centres or to the city, where they gradually found occupations in

low-level civil service positions, including teaching, law and medicine (Nicholson 1976; Rabe 2005).

Along with these internal migrations, freed slaves from other Caribbean islands came to work on newly

opened sugar estates in Guyana (Segal 1987).

These early labour migrations produced a diverse population, with East Indian and African

populations comprising the two largest ethnic groups, plus smaller groups of Chinese, Portuguese,

people of mixed descent and the autochthonous Amerindian populations (Premdas 1999). Colonial

practices produced deep divisions along ethnic group, rural-urban spaces and socio-economic levels.

Over the years, the African population became increasingly concentrated in skilled occupations in the

civil service, in the police and in the mining sector, while the Indian population remained largely rural

and with little access to education. Before 1961 all schools were administered by the Christian clergy,

which caused many Hindu and Muslim East Indians to turn away from education. The East Indian

population suffered particularly from weak political representation, given their limited role outside of

agriculture. However, rice farming proved to be a viable economic activity for this group, who was able

to acquire small plots of land, develop a niche in rice farming and export, leading to the gradual

improvement of the socio-economic conditions in the East Indian communities (Rabe 2005).

12 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

5 1953-1965: The long road to independence and the closure

of the British border

5.1 Political transitions and the effects of the 1962 British Immigration Act

British Guiana’s relatively stable political and social conditions in the 1950s suggested a speedy passage

to self-governance, but matters changed rapidly after the first elections held with universal adult

franchise in April 1953, which resulted in the victory of the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) led by

Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham. In August, the British government revoked British Guiana’s

constitution, removed the PPP from power and brought in British paratroopers (cf. Hintzen and Premdas

1982) with the pretext that violence was raging in the colony and order needed to be restored. In reality,

Britain intervened to prevent Jagan from implementing its alleged Communist agenda. A pervasive

campaign against the PPP ensued with the covert participation of the US government (Rabe 2005),

which relied on the dissemination of US anti-Communist literature for youth and adult readers to warn

about the possibility that British Guiana would become another Cuba. This propaganda caused

nervousness and frightened the merchant class, which began to leave the colony. These were often

people of middle- and upper-class Catholic Portuguese and Chinese Guyanese who, being involved in

commerce, feared the possible loss of their assets.

In 1957 Forbes Burnham founded the People’s National Congress (PNC), which took some

distance from Communist ideals and gained British and US support. The split of the PPP marked the

beginning of racialized politics as the PNC appealed principally to the Afro-Guyanese population.

Racial tensions that had been sown during colonialism were magnified in an ideological conflict.

Evidence shows however, that in reality class divisions may have been as important as ethnic divisions,

since the PNC was also supported by East Indian professionals, teachers and public servants (Jeffrey

1991). Ethnic violence in Georgetown, British Guiana’s capital, broke out in 1962 triggered by a

proposed government budget that would introduce duties on non-essential imports. In 1963, strikes and

demonstrations erupted in violence, with perpetrators being primarily Afro-Guyanese and victims

primarily Indo-Guyanese businesses and residences. By the end of 1964, there had been 368 political

and racial clashes, 200 deaths and 800 injuries in a country of approximately 600,000 people (Rabe

2005). Strong evidence shows that violent episodes were manoeuvred by US CIA agents who aimed to

destabilise Jagan and the PPP government (Hintzen and Premdas 1982).

At this time, Britain was becoming alarmed by the arrival of large numbers of British subjects

from many of its colonies. In Britain, public perception and attitudes towards immigrants from British

colonial territories deteriorated, exacerbated by long-term economic decline, high unemployment and

housing shortages (Davison 1962; Freeman 1987). Initially the British government attempted to curtail

immigration by appealing to Colonial governments to adopt measures that would discourage departures

to Britain. In British Guiana, the Executive Council discussed these appeals in 1961 and refused to

enact any migration-reduction measures, citing that ‘the size of the problem (migration) did not justify

establishment of the machinery proposed’.

4

In fact, while migration from the British West Indies had reached important levels by the late

1950s, only a small number of British Guianese had migrated to Britain (Marshall 1987; Peach 1968).

Early emigration to Britain was frequently linked to the pursuit of tertiary education, which would

guarantee a good standard of living and a prestigious social status upon return. As tertiary education

4

Executive Council: Minutes and Papers, 18 November 1961, 311.

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 13

was not available in the colony until the foundation of the University of Guyana in 1963, it emerged as

an important motive for migration among the interviewees who described Britain as a preferred

destination in their own migration trajectory or that of siblings, aunts and uncles who studied or became

nurses in Britain. Labour migration to Britain was less prevalent among Guianese as no organised

recruitment system was ever coordinated by the British Guiana colonial government, unlike those

established by London Transport, the National Health Service and British Rail in Barbados and Jamaica

(Mayor of London and Transport for London 2006). The low levels of emigration from British Guiana

in the 1950s may be explained by three factors: education was an important factor but the prerogative

of a limited few; potential Guianese migrant workers faced higher costs and longer journeys to reach

Britain than other West Indians; and British Guiana was enjoying a reasonably ‘healthy’ economy and

good political and economic prospects lowering migration aspirations (Baksh 1978).

5

Nonetheless, the

importance of colonialism in determining migration destination at this time was noticeable: of the

34,000 individuals born in British Guiana residing abroad in 1960 (roughly 6 percent of British Guiana’s

population), about 37 percent resided in Britain and more than 26 percent resided within regional British

possessions.

In 1962 Britain introduced the Commonwealth Immigration Act, signalling the British

government’s first step towards an increasingly hostile approach vis-à-vis the movement of its colonial

British subjects (Byron and Condon 2008). British Guyanese noticed these changes: in November 1961

the Minister of Communications and Works stated that ‘the recent increase in emigration from British

Guiana to the United Kingdom was due to the fear that legislation would be enacted in the United

Kingdom prohibiting immigration; people wanted therefore to get in before such legislation was

passed.’

6

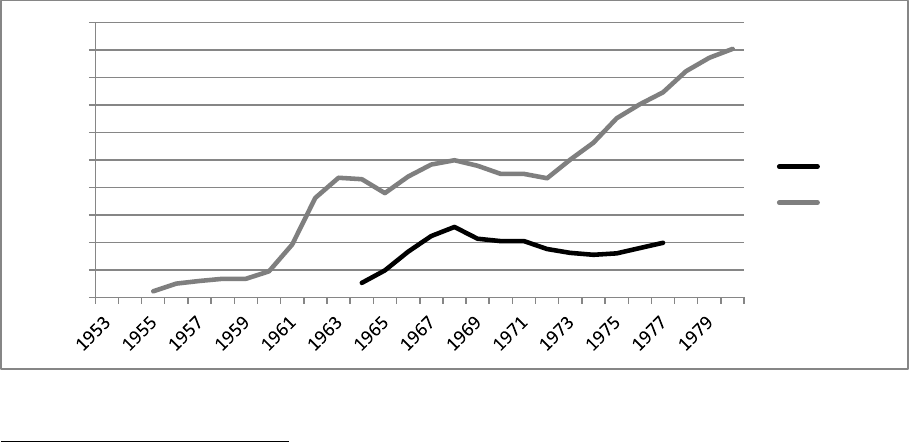

Migration data shows that emigration increased rapidly in 1961-1962 (Figure 3), coinciding

with the 1962 UK Immigration Act. According to official documents, the implementation of the Act

resulted in a drop in emigration in 1963 ‘to about half that level and was almost restricted to next of

kin, students and skilled workers’.

7

This suggests an inter-temporal substitution effect caused by an

attempt to beat the immigration restrictions, with an immediate decline after policy implementation.

Figure 3 Guyana’s total inflows and outflows, 1953-1980, 3-year averages

Source: DEMIG TOTAL Database

5

Although data quality is sketchy, documents of the colonial government confirm low emigration trends from

British Guiana to the United Kingdom (Executive Council: Minutes and Papers, 18 November 1961, 311).

6

Ibid.

7

1963 Labour Report of British Guiana, page 41.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Thousands

Inflow

Outflow

14 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

The halving of the flows to the UK in 1963 show that the Immigration Act contributed to the

sudden growth of migration (Peach 1968). Moreover, while emigration out of British Guiana until 1961-

62 was primarily oriented towards Britain, it gradually increased to other destinations as a reaction to

UK immigration restrictions (Figure 4). But while the closure of the British border may have propelled

emigration, we would be mistaken to think it was the only migration determinant. In fact, growing

instabilities and ethnic threats in British Guiana may partially explain the increasing volume of

emigration. In addition, in 1962-63 British employers demanded less labour due to an economic

slowdown, resulting in lower migrants’ arrivals, the return of men and the arrival of women and

children, marking a switch in migration composition (Peach 1968). The Act, in conjunction with lower

employment opportunities in Britain, may have contributed to the diversification of migration

destinations to the British West Indies and other unidentified destinations, suggesting possible spatial

substitution effects. For instance, Portuguese-Guyanese families were reported to have resettled

permanently in Canada, where there was a cultural affinity (and also part of the British Commonwealth)

and the opportunity to start a new life. As one interviewee eloquently stated, ‘the longshot of it all was

that it (the Act) somehow caused migrants to look for alternatives and they found them in the USA and

Canada.’ Figure 4 clearly shows the shift in migration destinations starting in 1963.

Figure 4 Total Outflows and Disaggregated Outflows from Guyana to a selected number of

countries

8

Source: Reported data from British Guiana Annual Reports on Labour 1950, 1955, 1956, 1963, 1965 and 1967; DEMIG TOTAL

database; DEMIG C2C database; and Peach 1968.

5.2 The opening of North American migration policies

This geographical shift was reinforced by the fact that as Britain closed its borders, North American

countries were opening new immigration channels: The US initiated small recruitment programmes,

including with British Guiana in 1960, when ‘…the Minister of Labour, Health and Housing […]

received a letter from the B.W.I. Central Labour Organisation in Washington asking for a plane load of

8

These data must be used with great caution due to their incompleteness, particularly the fictitious drop in

emigration from 1968 to 1973. Data for the United Kingdom are not available after 1967, while for Canada data

are estimated from 1964 to 1973 from data for the Caribbean as an aggregate figure. The total flow data represent

a more accurate representation of inflows and outflows, but cannot be disaggregated by country of future

destination.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1946

1948

1950

1952

1954

1956*

1958

1960

1962

1964

1966

1968

1970

1972

1974

1976

1978

1980

Thousands

Other country

Unidentified country

Canada

USA

British West Indies

UK

Total Flows, 2 year average

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 15

farm labourers for employment on US’ farms.’

9

While this programme involved low numbers of

temporary workers and contemporary accounts indicate that the absconding rates were low, it provided

early labour migration connections to the US.

10

11

US immigration policy was eased further in 1965

with the enactment of the US Immigration and Naturalization Act, which removed European-biased

national origin criteria and allowed channels for new groups of immigrants, including citizens of new

independent countries such as Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago. The Act also introduced non-

immigrant temporary visas for skilled, high skilled and temporary workers needed in the US labour

force, channels heavily utilised by Caribbean health care workers, particularly Jamaican nurses

(Nicholson 1985).

As early as the mid-1950s Canadian immigration policies also created new opportunities,

although most Caribbean people could only access Canada as domestic workers. In 1955, the Canadian

government introduced a recruitment programme for a few hundred Caribbean women each year (James

2007). This scheme was active in British Guiana, where the colonial government provided the recruits

with reimbursable funds for the cost of passages and incidental expenses, as well as training in home

economics.

12

Between 1956 and 1964, only 30 domestic workers were recruited every year;

13

however,

domestic workers would be eligible for Canadian citizenship at the end of their one-year contract.

14

Hence, these women had access and regularly used family reunification channels already in the mid-

1950s (James 2007). The 1962 Immigration Act of Canada finally eliminated racial discrimination and

emphasised education and skills in an attempt to counteract the inflows of family-sponsored unskilled

immigrants. Although this Act is generally seen as the opening of Canadian immigration, the easing of

restrictions was in fact true only for skilled individuals. Nonetheless, the notion of skills is time-

dependent and the types of skilled workers sought in the Canadian economy in the 1960s were not

highly educated, but rather professionals, teachers, technical and semi-skilled workers (Baksh 1978).

Among the Guyanese population, clerical and white collar workers as well as teachers benefited the

most from these policy changes. Interviewees stated that it was well known that there were jobs in

Canada and since Guyanese did not require a visa to travel to Canada, they could easily go and ‘explore’

opportunities.

5.3 Independence and the weakening of migration to Britain

In 1964, the political situation in British Guiana was dominated by electoral victory of the coalition

between the PNC, led by Burnham, and the United Front, led by D’Aguiar (Hintzen and Premdas 1982).

The coalition government largely excluded East Indians from exercising power and engaged in coercive

activities (i.e. strong presence of the police), worsening the country’s racial tensions (Hintzen and

Premdas 1982; Rabe 2005). Amidst concerns of escalating violence, British Guiana’s independence

talks resumed and independence was set for May 1966. This was surprising given the British

government’s principle to grant independence only under conditions of political and economic stability.

Britain’s realisation of its limited financial resources to administer the empire and the anti-colonial

movement were however, strong motives to grant British Guiana its independence (Rabe 2005).

9

Meeting of the Executive Council of British Guiana, 29th September 1960. ‘Recruitment of Farm Labour for the

United States of America.’

10

Ibid.

11

An interviewee indicated that he met a Guyanese in Boston who was the son of one of these farm workers. He

specified that a few of these farm workers settled in the Boston area in the 1960s.

12

Meeting of the Executive Council of British Guiana, 8

th

March 1960, L.56/147 IV. (10) ‘Recruitment of

Domestic Servants for Canada.’

13

British Guiana Labour Reports 1956, 1963, 1965 and 1967.

14

British Guiana Labour Report 1963:41.

16 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

The interviewees, regardless of their ethnic group, recalled that independence was widely

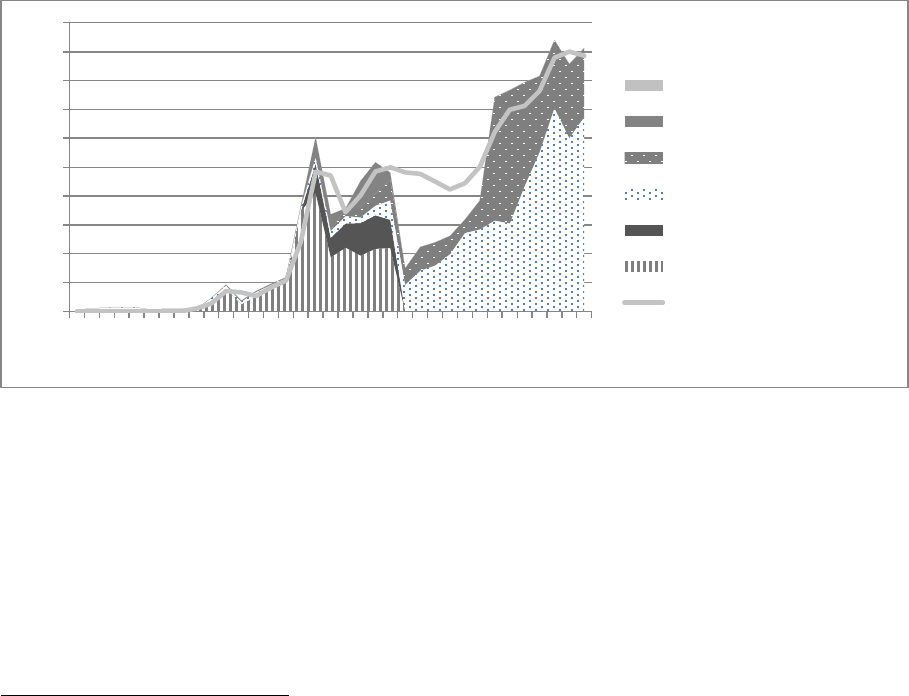

welcomed by the population, who had demanded it. Yet, emigration increased in 1965-66, suggesting

a second inter-temporal substitution effect created by independence. While emigration in 1962 affected

1 percent of the population, in 1966 it was slightly lower at less than .8 percent of the population,

pointing to a slightly stronger impact of border closure than independence. Migration stock data

confirms a drop in the size of the Guyanese community abroad in 1970, a decrease particularly visible

for the population in Britain (Figure 5). Overall, migration flows to Britain scarcely changed in the

1963-1968 period, while emigration towards the British West Indies and other destinations, including

Canada and the United States continued to grow, suggesting sustained spatial substitution. Hence,

although independence stimulated emigration, in no way did it fuel an exodus.

Figure 5 Guyana-born individuals residing abroad, by country of residence and Guyana’s

population size, 1960-2000

Source: World Bank Global Bilateral Migration Database; UN Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2010

Revision, Total Population by major area, region and country, annually for 1950-2100.

By independence in 1966, a combination of reasons contributed to emigration. First, the initial

growth of emigration in 1961-1962 was rooted in political reasons: The violent outbreaks starting in

1961 made living conditions in Guyana difficult, particularly for the Indo-Guyanese population, while

the closure of immigration channels into Britain in 1962 gave a clear signal of expiring migration

opportunities. This coincided with the opening of policies in North America, allowing for the initial

diversion of migration flows. Second, the economy and employment conditions in Britain, while better

than in Guyana, were not seen as attractive as the opportunities in North America. Third, among the

Guyanese who had gone to Britain to pursue an education with the intention to return, some pursued

work opportunities elsewhere. For some radically-minded intellectuals who may have held anti-

colonial, non-capitalist or non-alignment ideals, which were common in Guyana at this time, job

opportunities in developing countries may have been preferable to remaining in Britain. Fourth, the

unwelcoming social atmosphere in Britain had shattered the notion of belonging to the British

motherland instilled into the British subjects worldwide during colonialism. Fifth, some individuals,

whose family had migrated from Guyana to Canada and the US while they were in Britain, engaged in

step-wise migration from Britain to North America. Informants provided examples of how siblings in

Britain joined family members in Canada as most of the family had started a new life there. Fairly

rapidly, Britain lost its attractiveness as a migration destination. While some migration to Britain

continued in smaller numbers in later years, it remained stunted in comparison to the growing migration

trends within the Americas because of continually restrictive policies that severely curtailed even family

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

Population in Guyana

Guyanese abroad

All other countries

United States

United Kingdom

Canada

Population size

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 17

reunification (Segal 1998). Meanwhile, political uncertainties and insecurity in British Guiana were

increasingly felt by the population, leading a growing number of the population to choose emigration.

6 1966-1985: ‘Co-operative socialism’, authoritarianism and

emigration growth

6.1 The unintended migration stimuli of socio-economic reforms

After independence, the Guyanese government introduced a radical ideological reorientation that

intended to uproot Guyana’s economy from its colonial structure, create a self-reliance decolonised

society and redress the imbalances created during colonialism (Standing 1977). This process began in

1968, when Prime Minister Burnham began to pursue ‘co-operative socialism’, an ideology aimed at

giving workers control of the economy. The government’s commitment to this agenda was solidified in

1970 when the country became a Co-operative Republic and began to promote co-operatives,

implement price controls and a ban on imported foods, and in 1973 introduced a plan to feed, clothe

and house the nation by 1976 (Canterbury 2007). Among the state-led development strategies that were

implemented in the 1970s, four had long-term implications for Guyana, as well as seemingly unintended

migration effects: nationalisation; the national agricultural plan; education; and the national service.

6.1.1 Nationalisation

Nationalisation emerged as an attractive ideological, financial and symbolic reference as a result of

foreign-owned enterprises’ economic prominence and the public’s awareness of their role in leaking

profits outside of Guyana (Rabe 2005; Standing 1977). The government’s implementation of

nationalisation had severe effects on the nation’s financial and human capital, as the purchase of these

companies at negotiated prices caused the national debt to treble between 1970 and 1975. By 1976 the

state controlled 80 percent of the national economy (Thomas 1982), resulting in the nationalisation of

most jobs. Although the government indicated that no enterprise established after independence would

be nationalised (Thomas 1982), interviewees suggested that nationalisation was perceived as a threat to

private property, a sufficient reason to convince some people to leave Guyana.

6.1.2 The national agricultural plan

The national plan to reform agriculture implemented in the 1970s focused on mechanisation and large-

scale rice production to increase efficiency and competitiveness of Guyanese products on the global

markets (Canterbury 2007). Mechanisation was found however, to have increased rural unemployment

and underemployment (Standing and Sukdeo 1977) and rural-urban migration, represented largely by

the Indo-Guyanese population. Internal migration posed a growing threat to the urban economic base,

because of the already high urban unemployment levels in the early 1970s, and because rural migrants

encroached into sectors largely occupied by the Afro-Guyanese population (Hanley 1981). To curtail

rural-urban migration, the government promoted agricultural training and encouraged rural settlement,

but the results were disappointing and migration to the city continued uninterrupted (Standing and

Sukdeo 1977). Affected by a number of difficulties, by the 1980s the national agricultural plan proved

to be unsustainable and, most critically, food self-sufficiency was not achieved as large-scale production

had supplanted small-scale mixed farming (Canterbury 2007). In an indepth study of the village of

Ithaca, Nicholson (1976) found that the rural population was negatively affected by poor agricultural

growth and poor access to services and was aware of the wider employment opportunities and services

in the urban area. Family and friends in urban areas would facilitate migration and often determined

new migrants’ destinations as they linked specific rural areas to specific urban areas.

18 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

6.1.3 Education

The Guyanese government set out to provide educational facilities for the entire population as a means

to lift the socio-economic status and move away from colonial educational policy, which created a

privileged elite (Sackey 1977). By the 1970s, the government diversified secondary schooling away

from the traditional grammar system towards technical secondary schools geared to teach the technical

skills needed for the country’s development. From 1975-76 university fees were abolished, students

were financially compensated for following approved courses of study and were obliged to serve in the

National Services after graduation. This resulted in a significant increase of enrolment and what Baksh

(1978) called an ‘education explosion’. This phenomenon seems to have been the result of greater

access to education at a time when the population realised that education was the main avenue for

occupational and social mobility (Baksh 1978). In particular, Indo-Guyanese parents recognised that

village life would not allow their children to advance socially and economically and began to make big

sacrifices to educate their children (Hanley 1981). Concurrently, mechanisation had freed up young

men and women, who traditionally helped their fathers in rice production. An increasing number of

children were sent to Georgetown with high chances that they would not return to the village after

completing their education, as their life aspirations were linked to the urban environment and its more

prestigious employment market (Hanley 1981). This stimulated further rural-urban migration

(Nicholson 1976). Hanley (1981) also observed that villagers were acutely aware of how acquaintances

had managed to succeed through education and had become doctors or lawyers in Barbados and in

North America.

6.1.4 The National Service

Finally, the National Service was established as a prominent state-led development strategy, requiring

a compulsory year of paramilitary service for all university students, which usually placed them on

agricultural projects in the interior. This programme meant to instil a new value system in young

Guyanese, deprogramming neo-colonial values and helping the youth solve Guyana’s problems, in

accordance with the government agenda. This initiative generated different responses: while for some

it was an empowering experience, for others it was a deterrent to pursue tertiary education in Guyana.

During the interviews, it emerged that parents of Indo-Guyanese female students generally resisted

sending their daughters to the interior unsupervised. Moreover, the National Service was suspected to

be a recruitment system of the future government-aligned elite. Thus, the programme contributed to the

divisiveness of society (Baksh 1978) and, as confirmed during interviews, also pushed individuals to

seek educational opportunities overseas to avoid the National Service.

Although these development strategies were meant to generate self-sufficiency and instil pride

in Guyana, in reality they proved inadequate to diversify the economy, stimulate the private sector and

create sufficient jobs to meet the new occupational aspirations of an increasingly educated population.

The government attempted to resolve the unemployment problem by expanding the service sector,

which in 1970 employed nearly 44 percent of all Guyanese workers, and increased jobs in teaching, the

police, the army, and other public ventures such as the national insurance scheme and national banks

(Baksh 1978). However, this strategy was ultimately unable to reduce job shortages.

6.2 Widening authoritarianism and population movement control

Troubling political developments made the Guyanese population nervous as the Burnham government

gradually introduced policies that were at odds with democratic principles, creating an atmosphere of

fear and insecurity shortly after independence. In 1966 Prime Minister Burnham introduced the National

Security Act, which gave the police arbitrary power to search, seize and arrest anybody at will (Mars

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 19

2001). In 1968, the end of the PNC coalition with the United Front, a party that represented business

interests, caused greater political and economic uncertainty for middle- and upper-class Portuguese,

other minority European groups, and rich Indian business people. For this segment of the population,

emigration to Canada became increasingly attractive.

15

A system of overseas proxy voting, corruption, grafting and political oppression led to rigged

elections in 1968, 1973 and 1980 (Canterbury 2007; Jeffrey 1991; Rabe 2005). While in everyday life

and the courts, the government suppressed human rights, restricted the freedom of movement and

harassed political opponents. Attempts to stop the opposition culminated with the assassination of

Walter Rodney, leader of the Working People’s Alliance (WPA) in June 1980, while lawlessness

reigned as scare tactics targeted critics regardless of ethnicity (Jeffrey 1991; Rabe 2005). The 1980

Constitution confirmed Guyana as a co-operative republic and introduced the figure of a powerful

executive president (Polity IV 2010). In the five-year period between 1980 and 1985 politically

supported gangs commonly called ‘kick-down-the-door-gangs’ would use ambushes to attack wealthy

businessmen, usually Indo-Guyanese, creating a state of terror (Owen and Grigsby 2012).

By the early 1980s living conditions were grim. The population experienced direct

discrimination, either because of ethnic group or political affiliation, people were ‘watched’ and grew

alarmed by the increasing violence. An informant reported that people suffered from persecution,

humiliation on the job or at departure, as Guyanese were pulled off the plane as they attempted to

emigrate. This lead to what many interviewees described as sudden emigration: people did not discuss

emigration, not even with their immediate family, but had suddenly left with their spouse and children.

From the government’s perspective, people had ‘voted with their feet’ and, as one of the informants

indicated, the government seemed pleased to purge government dissenters who may have otherwise

voiced their opposition (Hirschman 1978). Emigration was also a financial concern for the government

however, as many Guyanese emigrants possessed assets and their departure was ‘draining wealth out

of Guyana’. In this vein, the government introduced a law preventing people from exporting foreign

currency, which then ‘justified’ stopping emigrants from leaving with even small amounts of cash.

6.3 Corruption, discrimination and the emigration of skilled workers

The emigration of skilled workers was not a new issue and it had been a publicly discussed subject since

independence (Sackey 1977).

16

In 1967 Prime Minister Burnham launched a remigration

(return/immigration) policy, and by 1970 national and non-national professionals were selected and

placed in posts including engineering, education, medicine, management, research and the social

services (Strachan 1980; Strachan 1983). Few returned through this scheme, mainly individuals with

high levels of commitment to Guyana’s development: Guyanese returning from Britain representing 61

percent of total returns (Strachan 1983). These returns partially explain the decrease in Guyanese-born

population in Britain in 1970 (Figure 5).

15

Unfortunately Canadian data for 1956-1973 is only available as an aggregate for the Caribbean region. However,

in 1974, immigration figures were at 4277, higher than inflows to the US, 3153, demonstrating the high

attractiveness of Canada in these early years.

16

The Guardian, May 26, 1966, p13,‘The Economics’, by Clyde Sanger, available at ProQuest Historical

Newspapers The Guardian and the Observer (1791-2003), accessed on 12 February 2013; Guyana Graphic,

Tuesday January 4, 1972, page 1, “Move by Health Ministry to halt brain drain” available at Guyana National

Library, Georgetown, Guyana; Sunday Argosy, February 25, 1973, p15, “Too many young people leaving

Guyana” by Humphrey Nelson, available at Guyana National Library, Georgetown, Guyana; Sunday Argosy,

August 12, 1973, “Brain drain: incurable cancer?”, By R.O. Bostwick, available at Guyana National Library,

Georgetown, Guyana.

20 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

These returns paled in comparison to increasing emigration flows of skilled professionals and

trained workers. Many skilled professionals who had run multinational companies left Guyana when

nationalisation was introduced (Standing 1977). Working in the public sector was increasingly

problematic as Guyana’s bureaucracy became a centralised tool for advancing political interests. As the

government engaged in a ‘spoils system’ that rewarded workers depending on their ethnic group and

political position (Baksh 1978), civil servants who chose not to be a pawn in the authoritarian system

opted for emigration (Hope 1977; Thomas 1982). In 1968 and 1970 respectively, 20 and 25 percent of

high skilled emigrants were individuals who before departure held professional or technical positions

such as doctors, lawyers, engineers, administrative posts and supervisors. Emigration of Indo-Guyanese

was particularly noticeable, prompted by fear and insecurity generated by the increasingly uncertain

political and economic future of Guyana (Sackey 1977). By the late 1970s the personnel situation in

Guyana was so critical that there were hardly any qualified individuals able to lead or carry out the

functions of the state, while poor recruitment policies and lack of proper manpower planning

contributed to the frustration of those individuals who remained in Guyana (Hope 1977; Standing 1977;

Standing and Sukdeo 1977). For most graduating students, a degree increasingly represented a ticket to

occupational mobility abroad (Baksh 1978; Sackey 1977).

6.4 Continual transition to North American destinations

As Guyana became increasingly inhospitable, the Guyanese population looked more and more to build

a future abroad. The progressive widening of British immigration control in 1968 meant that Guyanese

could migrate to Britain only as holders of employment vouchers or as dependents. The 1971

Immigration Act came into force in 1973 and removed ‘the automatic right of the Commonwealth

worker to remain here (in Britain) once he has arrived’.

17

However, ‘immigrants who had been

previously accepted for permanent residence in the United Kingdom were able to return […] after an

absence of up to 2 years and to bring in, or be joined by his wife, children under 18 and his elderly

parents, free of conditions.’

18

As the conditions worsened in Guyana in the early 1970s, Guyanese

returnees from Britain may have used this channel to re-emigrate to Britain, possibly explaining the

strengthening of the Guyanese community in Britain in 1980 (Figure 5).

The overall weakening of migration flows to Britain is however surprising since no travel visa

was required until 1997 and Guyanese would have been able to overstay or seek asylum, strategies used

to migrate to North America. Interviews offer possible explanations: first, the heightened levels of

immigration controls in the UK may have made the Guyanese community hesitant to support further

migration. A number of interviewees indicated that although they had family in Britain, these relatives

never ‘sent for them’ even during the harshest times in Guyana, while another interviewee pointed to

the general perception that Guyanese in Britain lost their ties to Guyana. Second, interviewees pointed

to the unattractive employment conditions in Britain by the 1980s. Third, interviewees recalled harsh

political and socio-cultural conditions well-captured by Enoch Powell’s 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech,

which advocated the immediate stop of immigration on the basis of Commonwealth immigrants’

incompatibility with British society. Such political propaganda reinforced the negative experiences of

West Indians living in Britain, making Britain a less desirable migration destination (Thomas-Hope

1980). Finally, the homogeneity of British society made Britain a place where it was difficult to ‘blend

17

Immigration Bill: Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Home Department, Cabinet, CP(70)126, 31

December 1970, The National Archives, Catalogue Reference: CAB/129/154

18

This clause existed in the proposal of the Bill in December 1970, cannot be found on the 1970 Act, but is found

in an extended form in the 1983 Statement of Changes in Immigration Rules, http://www.official-

documents.gov.uk/document/hc8283/hc01/0169/0169.pdf, and in today’s policy in a more limited version.

IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94 21

in’ and live as undocumented migrants, which deterred irregular immigration. While these factors alone

may not have led to a migration decline, the availability of alternative destinations helped to cast Britain

aside.

In North American, after the 1965 US immigration Act introduced skills criteria, the 1976

amendments to the Act restricted entry opportunities by requiring a job offer. Nevertheless, the

amendments also allowed immigrants from the Americas with a temporary or even an irregular position

who were already in the US to adjust their status (e.g. through marriage). Entry quotas were reduced

further in 1980; yet in 1982, the US Ambassador to Guyana announced that its government would offer

Guyana 11,000 permanent visas and 6,000 visitor visa, up from 6,600 and 5,000 respectively in 1981.

In 1982, US policy also introduced a new refugee category.

19

Guyanese increasingly applied for

permanent residence as spouses and children of US permanent residents, but irregular migration also

increased.

20

By this time, even rural Guyanese had become well-versed in regular migration regulations

and how the regulations could be circumvented. For instance, during the Vietnam War, one could

overstay and avoid deportation by volunteering for the US Army, a strategy reportedly used by

Guyanese (Hanley 1981).

Canada’s immigration policy followed a different path: While in 1967 Canada reinforced its

emphasis on skills by introducing the point-system, by 1973 labour shortages pushed the government

to introduce a temporary work visa programme. The 1976 Immigration Act embodied non-

discrimination, family reunification and refugee policy as the policy’s three pillars, but also continued

to emphasise skills, clearly expressing the Canadian government’s concerns with the composition of

migration more than its volume. In the early 1980s Canada’s policies became more selective by

restricting temporary workers and introducing a labour market test for low-skilled immigrants,

21

while

migration for high skilled and entrepreneurs was facilitated. For the rest of the 1980s, Canadian

migration policies attempted to regulate flows through frequent adjustment of immigration quotas,

which were lowered in 1983 and 1984. By 1985-86 Guyanese had become the top Caribbean nationality

of asylum seekers, mainly composed of Indo-Guyanese applicants. Canadian authorities approved 40

percent of asylum seeking applications, but many were considered economic refugees and were

rejected. Remarkably, the applications decreased starting in 1985, when Guyanese were obliged to

obtain a visa to travel to Canada.

22

6.5 The diversification of emigration

By the mid-1980s Guyana was on its knees (Rabe 2005). The promises of independence gradually gave

way to dismal conditions which socially and politically included discrimination, oppression,

victimisation, crime, violence as well as unemployment and food shortages that are very memorable

among Guyanese. Emigration was staggering as 47,000 Guyanese (43% of natural population increase)

migrated between 1970 and 1975 and 72,000 (70% of natural population increase) migrated between

19

Express Thursday June 17, 1982, p 15, ‘11,000 Guyanese get visas to live in the States’, available at Guyana

National Library, Georgetown, Guyana.

20

Guyana Chronicle, Wednesday, 16 June 1982, pp1 and 7, ‘Harsh measures demanded against US

immigrants…’, available at Guyana National Library, Georgetown, Guyana.

21

Data source: DEMIG POLICY database

22

Sunday Stabroek News. May 27, 2006 (missing year, 2006 assumed given the content) p3&9, ‘Guyanese still

applying in droves to Canada, but only 10% granted refugee status’ by Miranda La Rose. Unfortunately Canadian

refugee data (Refugees Landed in Canada – RLC) is only available after 1990.

22 IMI Working Papers Series 2014, No. 94

1976 and 1981 (Thomas 1982).

23

This period marked the maturation of skilled emigration with the

departure of all kinds of professionals who were discriminated against for not complying with political

agendas. Increasingly skills were recognised not as a way to contribute to Guyana’s development but

to emigrate, leading more people to upgrade their skills to migrate (Thomas 1982).

Gradually great hardship affected the entire population, leading all social sectors to emigrate

and increasingly concerning the lower classes (Canterbury 2007; Roopnarine 2013). North America

was the chosen destination by many who perceived that jobs were available and salaries were high,

although Guyanese frequently migrated through marriage or as family members of Canadian or US

permanent residents or citizens. In 1982, Guyanese applied as relatives of US citizens (71 percent) or