Report to Congressional Committees

March 1989

MEDICAID

Recoveries From

Nursing Home

Residents’ Estates

Could Offset

Program Costs

GAO/HRD-89-56

Human Resources Division

B-226448

March 7, 1989

The Honorable Lloyd Bentsen

Chairman, Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Henry A. Waxman

Chairman, Subcommittee on Health

and the Environment

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

This report discusses the potential for estate recovery programs to help offset state and

federal Medicaid nursing home costs while removing an inequity in the program. The

inequity involves some nursing home residents with homes having to contribute less toward

the cost of their care than recipients with more liquid assets. The report discusses the need

for the Congress to consider making mandatory the establishment of estate recovery

programs.

Copies of this report are being sent to the Secretary of Health and Human Services; the

Director, Office of Management and Budget; and other interested parties.

This report was prepared under the direction of Michael Zimmerman, Director, Medicare and

Medicaid Issues. Other major contributors are listed in appendix X.

Lawrence H. Thompson

Assistant Comptroller General

Executive Summ~

Purpose

An increasing proportion of Medicaid funds finance nursing home care

for people who become eligible because high medical expenses deplete

their financial resources. Such recipients, known as the medically needy,

must deplete their available financial resources before turning to Medi-

caid, but they are generally allowed to keep their homes for as long as

they or certain of their dependents need them.

Concerns about the treatment of the recipients’ assets have included:

l

that the elderly will dispose of their assets for less than their real value

in order to become eligible for Medicaid, and

l

that the elderly whose assets include a home may not have to contribute

as much toward the cost of their care as those whose assets are more

liquid.

Such actions cause the taxpayers to shoulder a greater portion of the

cost of care than would otherwise be required. These actions also create

an inequity between those with and without homes as part of their

assets.

The Congress has taken a series of actions to address the first concern,

recently requiring states to impose penalties on recipients found to have

transferred assets for less than their value within 30 months of apply-

ing for Medicaid. Also, states have been authorized, but not required, to

establish estate recovery programs to address the second concern.

Through asset recovery programs, states can recover from the estates of

nursing home recipients or their survivors a portion of the expenses the

state incurs in providing nursing home care. Estate recovery programs

require Medicaid recipients whose primary assets are their homes to

contribute toward the cost of their nursing home care in the same man-

ner required of recipients whose assets are in the form of stocks, bonds,

and cash. Unlike the payments made from liquid assets, however, pay-

ments from the home’s equity are deferred until the recipient and his or

her spouse and dependent children no longer need the home.

GAO

studied Medicaid nursing home programs in eight states, focusing

particular attention on the estate recovery program operated by Oregon.

The objective was to discover the potential financial impact of such pro-

grams on Medicaid and whether they provide a mechanism that is

acceptable to the elderly for sharing the costs of nursing home care.

Page 2 GAO/HBDs(Mg Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Executive Summary

Background

The Congress intends that all assets, including home equity, available to

Medicaid nursing home residents be used to help pay for their care.

However, to lessen the hardship on the family, the home-the primary

asset of most elderly

Americans

-is exempt in determining eligibility as

long as there is a spouse, dependent child, or certain other relatives liv-

ing in the home or the nursing home resident expects to return home.

By restricting transfers of the home and other assets to other than the

recipient’s spouse and/or placing a lien on a recipient’s house, states can

help ensure that a Medicaid recipient’s assets remain available to defray

Medicaid costs. Transfer-of-assets restrictions such as those recently

mandated through the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988

apply, however, only while the recipient is alive. Similarly, liens provide

only a mechanism for impeding improper transfers. Unless the state also

has an estate recovery program, it has no means to recover assets that

remain at the time of the recipient’s death or, if there is a surviving

spouse, at the time of the spouse’s death. (See pp. 17 to 19.)

In July 1988 the Department of Health and Human Services’

(HHS)

Inspector General reported

that

only 21 states and the District of Colum-

bia had established programs to recover correctly paid benefits from

recipients’ estates.

Results in Brief

Estate recovery programs provide a cost effective way to offset state

and federal costs, while promoting more equitable treatment of Medicaid

recipients. Oregon recovers about $10 for every $1 spent administering

the program, state officials estimate. Programs such as Oregon’s are a

logical extension of transfer-of-assets and lien provisions, providing the

mechanism for recovering those assets preserved through those

measures.

In the eight states studied, as much as two-thirds of the amount spent

for nursing home care for Medicaid recipients who owned a home could

be recovered from their estates or the estates of their spouses. If imple-

mented carefully, estate recovery programs can achieve savings, while

treating the elderly equitably and humanely. Advocacy groups for the

elderly in Oregon-

the state with the most effective program-told

GAO

that they had not heard any complaints about the program, and that the

state has been flexible in cases where recovery would cause a hardship

to the recipient’s family.

.

Page 3

GAO/ERD@%6 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Executive Summary

Principal Findings

Potential Recoveries Are

Significant

About 14 percent of the Medicaid nursing home residents in the eight

states

GAO

reviewed owned a home with an average value of about

$31,000, based on county records.

GAO

based this estimate on examina-

tion of Medicaid applications filed for random samples of residents

admitted to nursing homes during fiscal year 1986 in the eight states.

(see pp.

19-2Q)

By using home equity to defray Medicaid costs as Oregon does, the six

states that now lack recovery programs could recover about $85 million

from recipients admitted to nursing homes in fiscal year 1986. This rep-

resents 68 percent of the approximately $126 million cost to Medicaid of

nursing home care for those recipients who owned homes. (See pp.

20-22.)

In Pennsylvania and Michigan, attempts to establish estate recovery

programs through administrative procedures were blocked by legal chal-

lenges, state officials told

GAO.

Oregon avoided such problems by enact-

ing legislation specifically authorizing estate recoveries. (See p. 35.)

Recoveries From Spouses’

Because about one-third of Medicaid nursing home residents who own a

Estates

home have a spouse living in the community, a significant portion of

potential recoveries is lost unless a state authorizes recoveries from the

estates of surviving spouses. For example,

GAO

estimates that California

will recover about $15.8 million from the estates of Medicaid recipients

admitted to nursing homes in 1985 under its existing recovery program.

But it could recover an additional $11 million if the state enacts legisla-

tion to authorize recoveries from the estates of the surviving spouse

when he or she, in turn, dies. (See pp. 22 and 37.)

Limited HHS Role

HHS, responsible at the federal level for administering the Medicaid pro-

gram, has little information on effective recovery programs. Moreover,

the wording of regulations has contributed to confusion over whether

the law permits recoveries from the estates of Medicaid recipients who

were under age 65 when they were admitted to a nursing home. As a

result, both Oregon and California have limited their recovery programs

to recipients 65 or older. (See pp. 23-25.)

Page 4

GAO/HBD8966 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Executive Summary

Matters for

GAO

believes the Congress should consider making mandatory the estab-

Consideration by the

lishment of programs to recover the cost of Medicaid assistance pro-

vided to nursing home residents of all ages either from their estates or

Congress

from the estates of their surviving spouses. Establishment of such pro-

grams would be a logical extension of the transfer-of-assets provisions

recently mandated through the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of

1988. Estate recovery programs would help ensure that the assets pre-

served through the new transfer-of-assets provisions are eventually

used to defray state and federal Medicaid costs. (See p. 41.)

Agency Comments

HHS

and officials from the seven states that provided comments (Califor-

nia, Michigan, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin)

generally agreed that estate recovery programs could offset Medicaid

costs. Several state officials identified actions they plan to take to

encourage expansion of such programs. (See pp. 41-47.)

Page 6

GAO/HBD8966 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

-

Contents

Executive Summary

2

Chapter 1

8

Introduction

Medicaid

Medicaid Eligibility Criteria

Box-en-Long Amendment Limits Transfers

TEFRA Further Restricts Transfers and Authorizes

Greater Use of Liens and Estate Recoveries

Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988

Objectives, Scope, and Methodology

8

9

10

10

13

14

Chapter 2

Significant Recovery

States Need Both Transfer-of-Assets and Recovery

of Nursing Home Costs

Programs

From Estates Possible

About 14 Percent of Medicaid Nursing Home Recipients

Own a Home

17

17

19

Medicaid Pays Millions in Nursing Home Bills for

Homeowners

20

Medicaid Recovers Little of Its Nursing Home Costs From

Recipients’ Estates

21

Expanding Programs to Recover From Estates of

Institutionalized Recipients Under Age 66 Would

Increase Recoveries

23

Chapter 3

Oregon Recovery

HCFA Provides Limited Technical Assistance

Program an Example

The Recovery Process in Oregon

for Other States

Key Elements of Oregon’s Recovery Program

25

25

26

35

Chapter 4

40

Conclusions, Matters

Conclusions

40

for Consideration by

Matters for Consideration by the Congress 41

HHS Comments and Our Evaluation

41

the Congress, and

State Officials’ Comments and Our Evaluation

44

Agency and State

Comments

Page 6 GAO/IlRDWWl

Medicaid Estate Recoveries

-~-

Contents

Appendixes

Appendix I: Methodology Used to Determine Potential

Recovery for Medicaid Recipients Who Own Real

Property

48

Appendix II: Comments From the Department of Health

and Human Services

53

Appendix III: Comments From the State of California

Appendix IV: Comments From the State of Michigan

Appendix V: Comments From the State of Ohio

Appendix VI: Comments From the State of Oregon

Appendix VII: Comments From the Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania

58

60

61

63

64

Appendix VIII: Comments From the State of Washington

66

Appendix IX: Comments From the State of Wisconsin

67

Appendix X: Major Contributors to This Report

68

Tables

Table 1.1: Annual Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Table 2.1: Projected Number and Value of Real Properties

Owned by Medicaid Recipients in Eight States (1985)

Table 2.2: Estimated Medicaid Payments for Nursing

Home Residents in Eight States Who Owned Real

Property ( 1985)

13

20

21

Table 2.3: Projected Recoveries From Estates of Medicaid

Recipients Admitted to Nursing Homes in Eight

States (1985)

22

Figures

Figure 3.1: Oregon’s Recovery Process: Identifying Assets

Figure 3.2: Oregon’s Recovery Process: Tracking and

Preserving Assets

28

30

Figure 3.3: Oregon’s Recovery Process: Recovering When

Assets Become Available

33

Abbreviations

American Association of Retired Persons

Aid to Families With Dependent Children

HCFA

Health Care Financing Administration

HHS

Department of Health and Human Services

SSI

Supplemental Security Income

TEFRA

Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982

Page 7

GAO/HB.D-W56 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 1

Introduction

A Medicaid applicant’s ownership of a home does not usually make him

or her ineligible for Medicaid. Even though the home represents a poten-

tial resource to the individual that, upon sale or transfer, could be used

to defray the costs of medical care, the original Medicaid statute

severely limited states’ ability to restrict transfers, impose liens, or

recover correctly paid benefits from recipients’ estates. Specifically, the

Social Security Act prohibited states from imposing liens against any

recipient’s property before his or her death for Medicaid claims cor-

rectly paid on the individual’s behalf. In effect, the act generally prohib-

ited states from placing restrictions on the applicant’s ability to transfer

assets for the purpose of establishing Medicaid eligibility.

The law permitted states to recover Medicaid funds from the estates of

those recipients aged 66 or over but only after the death of the surviv-

ing spouse and only if there was no surviving child under the age of 21

or blind or disabled. Estate recovery programs were hard to administer,

however, because of the limits placed on the use of liens and transfer

restrictions. States were unable to identify and place liens on property

before the recipient’s death to ensure that the asset remained for future

recovery. This enabled an elderly individual to transfer his or her home

to a family member or friend and thereby assure that the home would

not be part of his or her estate and, therefore, would not be subject to

any recovery action initiated after the death of the individual.

In 1982, the Congress enacted measures to help prevent such practices

and ensure that all resources available to an institutionalized individual

not needed for support of a spouse or dependent child are applied

toward the cost of care. The Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of

1982 (TEFRA) made it easier for states to restrict transfers, impose liens,

and recover the costs of provided services from the estates of Medicaid

recipients. This report focuses primarily on estate recovery programs.

Medicaid

Medicaid is a federally aided, state-administered medical assistance pro-

gram that served about 22 million needy people in fiscal year 1985. It

became effective on January 1, 1966, under authority of title XIX of the

Social Security Act, as amended (42 U.S.C. 1396). Within broad federal

limits, states set the scope and reimbursement rates for medical services

offered and make payments directly to the providers who render

services.

The Health Care Financing Administration

(HCFA),

within the Depart-

ment of Health and Human Services

(HHS),

has overall responsibility for

Page 8

GAO/HBDs956 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 1

Introduction

administering the Medicaid program at the federal level. This includes

developing program policies, setting standards, and ensuring compliance

with federal Medicaid legislation and policies. The nature and scope of a

state’s Medicaid program are contained in a state plan, which, after

approval by

HHS,

provides the basis for federal funding.

Medicaid Eligibility

Criteria

Medicaid eligibility criteria are among the most complex of all assistance

programs. At a minimum, states must provide Medicaid coverage to all

persons who receive cash payments from the Aid to Families With

Dependent Children (AF’DC) program and almost all persons covered by

the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) pr0gram.l These Medicaid recipi-

ents are called categorically needy.

At their option, states can extend Medicaid coverage to certain groups,

including (1) institutionalized individuals with incomes up to 300 per-

cent of the

SSI

payment level (42 C.F.R. 436.231) and (2) those who

would be eligible for cash assistance if they were not in an institution

(42 C.F.R. 435.211).

States also can extend Medicaid coverage to individuals who are ineligi-

ble for cash assistance on the basis of income but whose income and

resources are considered insufficient to meet their medical needs. Pro-

grams for these medically needy persons accommodate individuals who

meet all the criteria for categorical assistance except for income and

who have incurred relatively large medical bills. Persons or families

with incomes above the medically needy income standard can deduct

certain incurred medical expenses for purposes of determining their

countable income to determine eligibility for Medicaid. In fiscal year

1986,34 states and the District of Columbia had medically needy

programs.

In addition to meeting income limits, Medicaid applicants’ assets must be

within specified limits. For example, to qualify for Medicaid as an SSI

recipient in 1988, an applicant could have a home of any value but could

not have liquid assets worth more than $1,900 for an individual and

‘Fourteen states limit Medicaid coverage of SSI recipients by requiring them to meet more restrictive

eligibility standards in effect before the January 1,1972, implementation of SSI, the Congressional

Research Service reported in July 19%‘. States choosing this option must allow applicants to deduct

medical expenses from income to establish eligibility. The 14 states (Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois,

Indiana, Minnesota,

Missouri,

Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio,

Oklahoma, Utah, and Virginia) are referred to commonly as “209 (b) states.”

Page 9

GAO/HI@B69 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 1

introduction

-

$2,850 for a couple. Under certain circumstances, states can impose

more stringent asset limits for SSI beneficiaries.

Asset limits for medically needy programs vary by state, but must be

(1) at least as liberal as the highest limits allowed for cash assistance

recipients in the state and (2) the same for all covered groups. The liquid

asset limits for a family of two ranged from $2,250 to $6,450 as of the

second quarter of 1987.

According to the Congressional Research Service, the majority of elderly

persons who become eligible for Medicaid’s nursing home benefit do so

only after they have spent down to Medicaid income and asset limits.

Generally, they enter the nursing home as a private pay patient and con-

vert to Medicaid after having spent their “excess” income and resources

on nursing home care.

Middle-income nursing home residents with sizeable assets may find it

difficult to qualify for Medicaid. This creates an incentive to transfer or

otherwise dispose of assets for less than fair market value in order to

establish Medicaid eligibility.

Boren-Long

Amendment Limits

Transfers

In an attempt to limit the ability of individuals to get around Medicaid

asset limits by transferring assets, the Congress passed the Roren-Long

Amendment of 1980, which permitted states to restrict transfers of non-

exempt assets. This amendment had limited effect, however, because

home equity-an exempt asset-represents the primary asset of most

elderly. Under the Boren-Long Amendment, a home can be transferred

to a son or daughter or other person at any time without affecting Medi-

caid eligibility.

TEFRA Further

Restricts Transfers

and Authorizes

Greater Use of Liens

To further limit the ability of individuals with assets that could be used

to pay for their nursing home care to give those assets away in order to

establish Medicaid eligibility, the Congress enacted section 132 of

TEFRA.

The act modified provisions of the Social Security Act (section 1917) by

authorizing states to place further restrictions on asset transfers, thus

and Estate Recoveries

making it easier to impose liens against the assets. TEFRA also established

the conditions under which states can undertake estate recovery. The

changes in the lien and transfer-of-assets provisions should enhance

states’ ability to operate effective programs.

HHS

noted in its implement-

ing regulations that the

TEFRA

provisions are

Page 10

GAO/HRD-89-66 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 1

Introduction

$6

.

intended to assure that all of the resources available to an institutionalized

individual, including equity in a home, which are not needed for the support of a

spouse or dependent children, will be used to defray the costs of supporting the

individual in the institution. In doing so, it seeks to balance government’s legitimate

interest in recovering its Medicaid costs against the individual’s need to have the

home available in the event discharge from the institution becomes feasible.”

The original transfer-of-assets provisions of TEFRA permitted states to

deny Medicaid assistance to any individual who otherwise became eligi-

ble because he or she disposed of resources for less than fair market

value within 2 years of applying for Medicaid or at any time after this

period. The time period was subsequently extended to 30 months by the

Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988 (see p. 13). A Medicaid

recipient may be declared ineligible if the home, an excludable asset, is

transferred for less than fair market value to anyone other than the

spouse, child under 21 years of age, or child who is blind or disabled

while the recipient is in a nursing home. Transfer-of-assets policies have

been adopted by 49 states.

TEFRA allows a state to place a lien against a recipient’s real property for

the purpose of recovering correctly paid Medicaid benefits if the state

can reasonably determine that the recipient is not expected to return

home. A state may not place a lien on an individual’s home if his or her

spouse or dependent child is lawfully residing in the home. In addition, a

lien must be removed if the recipient returns home. Liens are not self-

executory, but merely impede the ability of the property holder to con-

vey the property. If a lien exists, the property holder must satisfy the

lien before the property may be sold or transferred. The lien holder-in

this case the state Medicaid agency-does not have to wait until the

property is sold or transferred to recover; it can itself force the sale of

the property to satisfy its claim. Only Alabama and Maryland intention-

ally place liens prior to death to recover correctly paid benefits provided

to Medicaid nursing home residents, according to the

HHS

Inspector Gen-

eral’s June 1988 report.

Finally, TEFRA established conditions under which states can defray the

costs of Medicaid assistance paid on behalf of nursing home residents

through estate recovery. Under an estate recovery program, the state

files a claim against the estate for the cost of Medicaid assistance pro-

vided.’ As in the prior statutes, recovery cannot be made until (1) the

death of the recipient’s spouse and (2) the recipient has no surviving

‘If the estate is not settled in probate court, the state can seek reimbursement from the executor of

the estate.

Page 11

GAO/lIlUHWS6

Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 1

Introduction

-

child who is either under 21 or who is blind or disabled. In addition,

TEFRA provided that recovery cannot be undertaken based on a lien

imposed on the home if certain relatives have resided there since the

Medicaid recipient moved into the institution.3 Despite these limitations,

designed to prevent estate recoveries from creating undue hardship on

the Medicaid recipient’s family, TEFRA enhanced states’ abilities to oper-

ate effective recovery programs by helping ensure that assets were not

disposed of for less than fair market value in order to establish Medicaid

eligibility or preserve an inheritance.

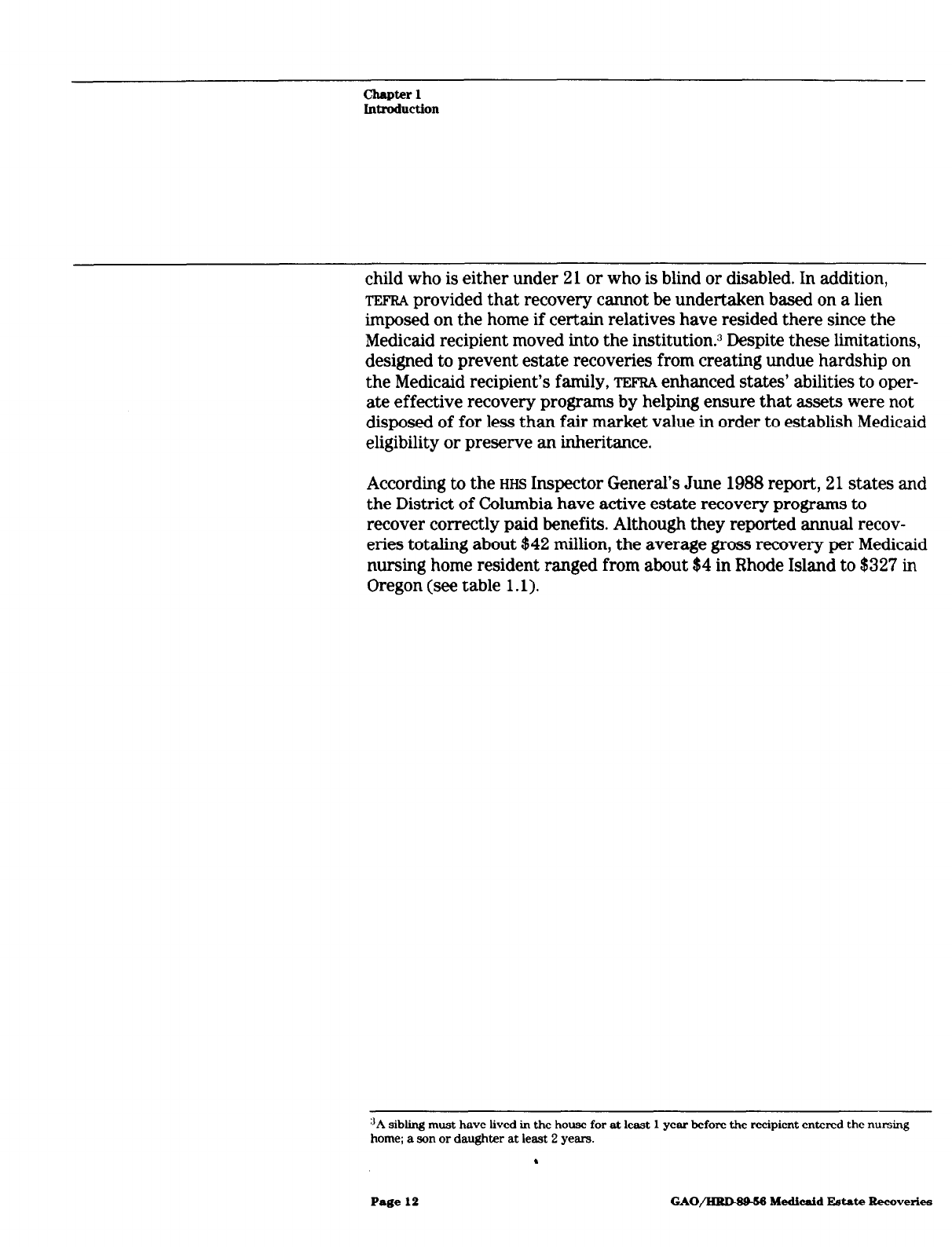

According to the

HHS

Inspector General’s June 1988 report, 21 states and

the District of Columbia have active estate recovery programs to

recover correctly paid benefits. Although they reported annual recov-

eries totaling about $42 million, the average gross recovery per Medicaid

nursing home resident ranged from about $4 in Rhode Island to $327 in

Oregon (see table 1.1).

“A sibling must have lived in the house for at least 1 year before the recipient entered the nursing

home; a son or daughter at least 2 years.

.

Page 12

GAO/llRMSM Medicaid Estate Recoveries

-r

Chapter 1

Inboduction

Table 1.1: Annual Medicaid Eatate

Recoveries

State

Alabama

California

Connecticut

2.100900

250,000 67.55

Amount of cost of

recovery’ recovery

$202,000 $55,000

12.000900 625600

Average gross

recovery per

Medicaid nursing

home resident

$9.74

91.37

District of Columbia 300,000 129,408 95.39

%ridab 640,941 c 17.00

Georgiab 1,089,358 c 30.35

Hawaii 68,208 8,280 16.78

Illinois 1,620,OOO 70,400 22.08

Indianad 400,000 c 9.86

Maryland 1,230,071 104,000 45.91

Massachusetts 4.800.000 93.450 109.05

Minnesota 4,722,895

‘

100.80

Missouri 453,000 21,391 15.53

Montana 150,000 lF900 29.93

New Hampshire 900,ooo 66,000 160.11

New Jersev 435.000 150,000 13.51

New Yorkb

North Dakota

5,942,995

c

53.62

316,955 34,200

5176

Oregon

Rhode Island

4,000,OOO 306,000

327.44

45.000 26.000

4.24

Utah 230,000

45,000

40.74

Vermont

TOtal

69,326 5,667

20.34

$41,715,749

$2,005,396

Source: Medicard Estate Recoveries, Office of Inspector General, HHS OAI-69-86-06678, June 1966,

p, 27.

aThe Inspector General’s report does not state the trme frame for reported recoveries except where

noted.

‘Amounts listed as recovenes are those reported to HCFA as “probate recoveries” in federal fiscal year

1985.

‘Unknown.

dlndrana no longer tracks estate recoveries. This figure is a projection based on past recovery perform-

ance.

Medicare Catastrophic

The Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988 amended TEFRA provi-

Coverage Act of 1988

sions pertaining to Medicaid estate recoveries. The act extends (to 30

months) and makes mandatory the restrictions on transfers of assets for

less than fair market value. This should help ensure that resources

remain available for later recovery. Second, the act makes it easier for a

.

Page 13

GAO/Hl?DW-66 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 1

Introduction

couple to qualify for Medicaid by requiring states to exclude more

income and resources in determinin

g eligibility if there is a noninstitu-

tionalized spouse. Because not as much of a couple’s income must be

applied toward the cost of care, these provisions will make it easier for

middle-income elderly to spend down to qualify for Medicaid and this

should increase recovery potential. Finally, the act requires the Secre-

tary of

HHS

to study the means for recovering the amounts from the

estates of deceased beneficiaries (or the estates of spouses of deceased

beneficiaries) to pay for nursing home services furnished under Medi-

caid. The Secretary was required to report to the Congress no later than

December 3 1, 1988, and to include appropriate recommendations for

changes.

Methodology

efforts to reduce program costs

by using the estates of Medicaid

nursing

home recipients or their surviving spouses to recover all or part of the

costs of care paid for by Medicaid. Our specific objectives concerning

estate recovery programs were to

l

identify key elements of effective programs,

l

estimate potential savings from establishment or expansion of

programs,

. identify barriers to the establishment of programs, and

. evaluate policy implications of programs.

We chose the Oregon program to identify the key elements of a success-

ful estate recovery program because it reported annual recoveries per

nursing home recipient more than twice those reported by any other

state. In addition, Oregon has been mentioned by

HCFA

as a model pro-

gram. In Oregon, we (1) reviewed pertinent laws, regulations, and proce-

dures supporting the estate recovery program, (2) obtained the views of

state officials on the elements of their program that they believed were

most important to its success, and (3) obtained the views of representa-

tives of advocacy groups for the elderly, such as the Gray Panthers, the

American Association of Retired Persons

(AARP),

United Seniors, and the

Senior Law Center.

To determine the potential for Medicaid cost savings from the establish-

ment or expansion of estate recovery programs, we reviewed the Medi-

caid applications for 200 randomly selected nursing home residents

from Oregon and seven other states. We selected six states (Michigan,

Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin) because they

Page 14 GAO/IllUM946 Medicaid Estate Recoveriea

Chapter 1

Introduction

did not have recovery programs and had among the largest Medicaid

nursing home programs. We selected California because it (1) operates

an estate recovery program but was recovering significantly less per

recipient than Oregon when we began our review and (2) accounts for

about 8 percent of all Medicaid nursing home payments.

In each state, we reviewed the Medicaid application (or

SSI

application if

Medicaid eligibility was established based on

SSI

eligibility) for 200 ran-

domly selected Medicaid recipients 66 years of age or older who were

first admitted to nursing homes in calendar year 19EK4 We selected

1986 as a sampling time frame rather than 1986 or 1987, to enable us to

obtain actual Medicaid cost data on as many recipients as possible.

Using the applications, we identified recipients who declared real prop-

erty ownership. In 13 counties in seven states, we reviewed county

records at the offices of the county assessors and treasurers to deter-

mine whether recipients (1) owned real property that was not declared

on their applications or (2) transferred property for less than fair mar-

ket value within 2 years of or after applying for Medicaid. Because our

work in the 13 counties did not identify many instances of home owner-

ship or transfers not disclosed on the applications, we decided to limit

our evaluation to home ownership disclosed on the Medicaid and/or

SSI

application.

For recipients with real property, we contacted the county assessor’s or

treasurer’s office to determine the value of the property. We then esti-

mated potential recoveries from the estates of recipients with real prop-

erty based on the policies and procedures followed in the Oregon

recovery program. Finally, we projected recoveries to the universes for

each of the eight states. Our methods for estimating potential recoveries

are discussed in more detail in appendix I.

To identify barriers to the establishment or expansion of estate recovery

programs, we (1) interviewed Medicaid officials in the eight states;

(2) attended a legislative hearing in the state of Washington on proposed

estate recovery legislation; (3) interviewed

HCFA

headquarters and

regional office officials to determine

HCFA’S

role in assisting states in

establishing recovery programs; and (4) interviewed representatives

from

AARP,

the Gray Panthers, and advocacy groups for the elderly in

Oregon about the Oregon program.

‘We limited our review to recipients 65 or older

because

HHS, in publishing its implementing regula-

tions, appeared to limit recoveries to that age

group.

Page 16

GAO/HRD-S956 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 1

Introduction

-

Our work was done between September 1986 and August 1987 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Page 16 GAO/IIRD-WM Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Significant Recovery of Nursing Home Costs

From Estates Possible

Many elderly who

own

a home when they enter a nursing home still own

it when they die. States that do not operate effective estate recovery

programs lose the opportunity to use this primary asset of about

one-

fourth of Medicaid recipients-their

home

equity-to defray Medicaid

costs. This is because transfer-of-assets provisions do not apply to assets

remaining at the time of the Medicaid recipient’s death, and liens are not

self-executing.

Of elderly Medicaid recipients admitted to nursing homes during calen-

dar year 1986 in the eight states reviewed, about 14 percent owned a

home or other real property (such as a farm) at the time they applied

for Medicaid. The average value of the real property they held based on

county assessment records was about $31,000. We estimate that

although Medicaid will pay an average $12,000 in nursing home bills for

those recipients, only about $1,360 of those payments is likely to be

recovered because

l

six of the eight states had no programs to recover their Medicaid nursing

home costs from

the

estates of Medicaid recipients and their spouses,

and

l

one state (California) had a recovery program but was not recovering

from the estates of surviving spouses.

If the seven states had had programs similar to Oregon’s, we estimate

that an additional $6,716 on average could have been recovered per

recipient.

Another opportunity for recoveries was lost in all eight states because

HCFA

regulations did not clearly indicate that recoveries were permitted

for institutionalized recipients under age 66. We did not estimate poten-

tial recoveries for this group, but believe

they

could be significant based

on

the

extent of home ownership in younger age groups.

States Need Both

Estate recoveries are an essential component of state efforts to ensure

Transfer-of-Assets

and

that Medicaid recipients’ assets are used to defray Medicaid costs. In

effect, a state that has a transfer-of-assets policy but

no

recovery pro-

Recovery Programs

gram ensures

that

the home remains available to defray Medicaid costs

while

the

recipient is alive, but fails to recover upon

the

death of the

recipient, even if there is

no

surviving spouse. The absence of an estate

recovery program also creates inequities in the treatment of Medicaid

recipients and their heirs, allowing recipients who still own a home at

the time of death to leave an estate, while requiring those

that

do not

Page 17 GAO/HRD-89-56 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 2

Significant Recovery of Nursing Home Costa

From Estates Possible

own a home to apply most of their liquid assets toward the cost of their

care before they become Medicaid-eligible.

The Congress intended to enable states to require that all of an institu-

tionalized recipient’s available resources be used to defray the costs of

institutionalization (section 1917, Social Security Act). As we discuss on

pages 10-12, such resources include equity in a home. These and certain

other resources, however, are not available to help pay for institutional

costs while the assets are needed to support a spouse or dependent child

or if there is a chance that the recipient will return home. Each of the

states we reviewed had established a transfer-of-assets policy to prevent

an individual from transferring assets to other than the spouse or

dependent child in order to establish Medicaid eligibility. But six of the

eight states (Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington, and Wis-

consin) had not, at the time of our review, established an estate recov-

ery program.

Without a recovery program, a transfer-of-assets policy leaves the

states without a mechanism to use assets remaining at the time of death

to defray Medicaid costs. Also, any such assets revert to the recipient’s

estate and can be transferred to the recipient’s nondependent children

or other heirs without first being used to defray Medicaid costs. The

following hypothetical example illustrates the inequities that could

result.

Example 1-A widow who had been living alone in her $40,000 home

enters a nursing home, but expects to return home. The widow’s home is

exempt in determining Medicaid eligibility. If the woman died after 1

year in the nursing home without selling the home, her heirs would

inherit the home and none of the proceeds from its sale would be used to

repay the Medicaid program for the $16,000 in nursing home payments.

However, if the home had been sold before she died, the widow would

be ineligible for Medicaid benefits until the remainder from the sale of

the home had been spent down to the $1,600 Medicaid asset limit. In

addition, proceeds from the sale could have been used to repay the

Medicaid program for the nursing home costs already incurred if the

state had placed a lien on her property before she died. The woman’s

heirs would have received only those funds remaining at the time of

death that were not needed to pay for the parent’s nursing home care.

Finally, if the widow had $40,000 in savings but did not own a home,

she would have been required to spend down to the Medicaid asset limit

($1,600) as a private pay patient before she could become eligible for

Page 18

GAO/IiRBWM Medicaid Estate Recoveries

-

Chapter 2

Significant Recovery

of

Nursing Home Costa

Prom Estates Podble

Medicaid. After about 2 years as a private pay patient, she could have

established Medicaid eligibility. During those 2 years, the Medicaid pro-

gram would have avoided about $30,000 in nursing home payments. The

adult child would be left with no inheritance.

The above example shows that a recipient who does not own a home or

sells a home while in a nursing home must apply his or her assets

toward the cost of nursing home care. On the other hand, the recipient

who still owns a home at the time of death need not apply those assets

toward the cost of care, unless the state has established an estate recov-

ery program.

About 14 Percent of

In the eight states reviewed, the percentage of nursing home recipients

Medicaid Nursing

in our sample who owned a home or other real property when they

applied for Medicaid ranged from 8.6 percent in Pennsylvania to 21 per-

Home Recipients Own

cent in Wisconsin (see table 2.1). An average of 14 percent of Medicaid

a Home

nursing home recipients sampled in the eight states owned real prop-

erty. Of the property owners, only about 7 percent indicated they were

still making mortgage payments (see p. 48 for a more detailed discus-

sion). In each state, our random sample consisted of 200 individuals 66

years or older, whose Medicaid applications we reviewed to identify

whether they owned a home or other real property at the time of

application.

The average value of real property owned by Medicaid nursing home

recipients sampled in the eight states was $30,712, ranging from about

$23,000 in Michigan to $39,000 in Washington (see table 2.1). We deter-

mined the value of the properties from county records (see p, 49 for a

discussion of these sources).

Page 19

GAO/HID&t%

lkdicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 2

Significant Recovery of Nursing Home Costa

From Estates Possible

Table 2.1: Projected Number and Value

of Real Properties Owned by Medicaid

Recipients in Eight States

(1985)

State

California

Recipients

Projected home

admitted to

ownership

Average

value of real

nursing homes Number

Projected total

Percent

wwerty~

value of property

29,416

3,677 12.5

$36,168

$132.989.736

Michigan

9,711

874 9.0 23,287

203352,838

Ohio

13,000

2,340 18.0 28,214

66,020,760

Oreaon

3,018

453 15.0 37.234

16.867.002

Pennsylvania

17,374

1,477 8.5 26,035

38,453,695

Texas

14,980

2,846 19.0 25,476

72.504.696

Washington

7,122

783 11.0 39,162

30,663,846

Wisconsin

9,520

1,999 21 .o 32,012

63,991,988

Total

104,141

14,449 (14.01 $30.712

5441.844.561 b

%epresents the average value of real property for the 228 recipients in the eight state samples

bThls figure IS accurate withln plus or minus $64,662.650 at the 95-percent confidence level

We estimate that 14,449 Medicaid recipients admitted to nursing homes

in 1985 in the eight states at the time of admission owned real property

valued at about $442 million.

Medicaid Pays Millions

For each of our sample recipients who owned a home or other real prop-

in Nursing Home Bills

erty, we estimate that Medicaid will pay nursing home costs ranging

from $10,281 in Texas to $14,745 in Washington over the duration of his

for Homeowners

or her nursing home stay (see table 2.2). For the eight states we

reviewed, we project total Medicaid payments of about $176 million for

the estimated 14,449 recipients admitted to nursing homes in 1985 who

owned real property. We based our estimates on actual Medicaid pay-

ments in 1985 and 1986, and projected payments for those who were

still in the homes at the beginning of 1987.

Page 20

GAO/HRD&L56 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

chapter 2

Significant Recovery of Nursing Home C.&a

Prom Estates Possible

Table 2.2: Estimated Medicaid Payments

for Nursing Home Residents in Eight

Average Estimated total

States Who Owned Real Property

(1985)

Projected recipients Medicaid Medicaid

State

owning real property payments

payments

California

3,677 $12,523 -$46,047,071

Michigan 874 13,409 11,719,466

Ohio

2,340 12,649

29,598,660

Oregon 453 9,674 4,382,322

Pennsylvania 1,477 10,463 15,453,851

Texas 2,846 10,281 29,259,726

Washington 783 14,745 11,545,335

Wisconsin 1,999 13,802 27,590,198

Total

14,449

$12,193 $175,596,62g8

aThis figure is accurate wlthln plus or minus $X4,912,950 at the 95-percent confidence level

Medicaid Recovers

Little of Its Nursing

Home Costs From

Recipients’ Estates

A state cannot use a Medicaid recipient’s home equity to defray Medi-

caid costs unless the home is either (1) sold before the recipient dies or

(2) the state operates an estate recovery program (see pp. 10-12). At the

time we completed our field work, 95 of the 228 recipients in our sam-

ples who owned a home at the time they entered the nursing home were

deceased. Of those 95 recipients, 91 owned their homes at the time of

death. Because Medicaid recipients in the eight states generally retained

ownership of their homes until death, only Oregon and California-the

two states with recovery programs-could use recipients’ home equity

to defray Medicaid costs.

In the eight states reviewed, only about $19.5 million of the estimated

$176 million in Medicaid payments for recipients admitted to nursing

homes in 1985 who owned real property will be recovered (see table

2.3). To determine the potential effect of a recovery program on Medi-

caid costs, we applied the recovery procedures used by Oregon to the

cases in all eight states. Oregon recovers up to the actual cost of Medi-

caid services provided from the recipient’s estate, or, if there is a surviv-

ing spouse, from the spouse’s estate. (See app. I for a more detailed

discussion of the methods used to estimate potential recovery.)

Page 21 GAO/HRD8%56 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 2

Significant Recovery of Nursing Home Costa

From Estates Possible

Table 2.3: Projected Recoveries From

Estates of Medicaid Recipients Admitted

Estimated

to Nurring Homes in Eight States

(1985)

Projected

recoveries under recoveries based

State 1986 state law on Oregon law Increase

California

$15,801,100

$26,740,760

$10,939,660

Michigan 0

9,869,386 9,869,386

Ohio

0

21,226,600 21,226,604

Oregon

3,779,427 3,779,427

0

Pennsylvania

0

8,447,847

8,447,847

Texas

0 20.297900

20.297900

Washington

Wisconsin

Total

0

6,890,606 6,890,606

$19.580,52~

18,368,170 18,368,170

$115,620,696”

$96,040,169

aThis figure is accurate within plus or minus $23,835,640 at the 95-percent confidence level

By establishing recovery programs patterned after Oregon’s, the six

states without recovery programs could defray about $85 million of the

estimated $125 million in Medicaid nursing home payments they will

incur for recipients owning a home. Although California operates a

recovery program, it does not attempt to recover from the estates of

surviving spouses because state law does not authorize such recoveries.

We estimate that California could increase recoveries by about $11 mil-

lion by recovering from the estates of surviving spouses. Overall, in the

eight states we sampled, about one-third of the recipients who owned

property had a surviving spouse, making recoveries from their estates

an important component of states’ efforts to defray Medicaid costs.

During the course of our review, Texas and Washington enacted legisla-

tion establishing recovery programs. However, neither program offers

the recovery potential of the Oregon program. Specifically:

. Texas’s law does not authorize recovery from spouses’ estates. About

$6 million of the approximately $20 million in projected recoveries in

Texas would be from spouses’ estates.

. Washington’s law, enacted in 1987, does not allow recovery from real

property sold for less than $50,000 if there are any surviving children,

even if they have reached adulthood. For real property sold for over

$50,000, recovery is limited to 35 percent of the value if there is an

adult child. These provisions reduce projected recoveries in Washington

from about $7 million to about $218,000.

.

Page 22 GAO/HRD43H56 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 2

S&i&ant Recovery of Nursing Home Coetu

Prom Eetates Possible

Expanding Programs

Neither Oregon nor California attempts to recover from the estates of

to Recover From

institutionalized recipients under age 66. Officials from both states told

us that they believed that recoveries from recipients under age 66 were

Estates of

authorized by section 1917 only if a lien were placed before the death of

Institutionalized

the recipient. But our analysis of the law and discussions with

HCFA

offi-

Recipients Under Age

cials indicate that recoveries from the estates of permanently institu-

tionalized recipients under 66 are permitted. Because the rate of home

65 Would Increase

ownership is higher for individuals under age 66 and about 14 percent

Recoveries

of skilled nursing home residents were under 66 in fiscal year 1983,’

recoveries could be significant.

Section 1917(b) reads, in pertinent part,

“( 1) No adjustment or recovery of any medical assistance correctly paid on behalf of

an individual under the State plan may be made, except-

“(A) in the case of an individual described in subsection (a)( l)(B) of this section

[which refers to permanently institutionalized individuals whom states require to

pay most of their income for medical care], from his estate or upon sale of the prop-

erty subject to a lien imposed on account of medical assistance paid on behalf of

such individual. and

“(B) in the case of any other individual who was 66 years of age or older when he

received such assistance, from his estate.”

California’s Department of Health Services interprets section (b)(l)(A)

as applying only to institutionalized recipients whose estate or property

is subject to a lien, Department officials told us. Their recovery program,

they said, is operated under section (b)(l)(B), which limits recovery to

estates of recipients 66 years of age or older.

Officials from Oregon’s Estate Administration Unit also believed section

1917 precluded recoveries for recipients under age 66, but for a differ-

ent reason. They interpreted the section as requiring that

both

“A” and

“B” must be satisfied in order to recoyer. In other words, they believed

the individual had to be both institutionalized and over 66 years of age

before estate recovery could be done.

HHS

may have contributed to the confusion by its statement in the Fed-

eral Register notice

that

published the final regulations to implement the

lien and estate recovery provisions of TEFRA:

‘HCFA, Program Statistics, Medicare and

Medicaid Data Books, 1986, p. 86.

.

Page 23

GAO/HlUMM6 Medicaid E&ate Recoveries

Chapter 2

Significant Recovery of Nursin~~ Home Costa

Prom Estates Possible

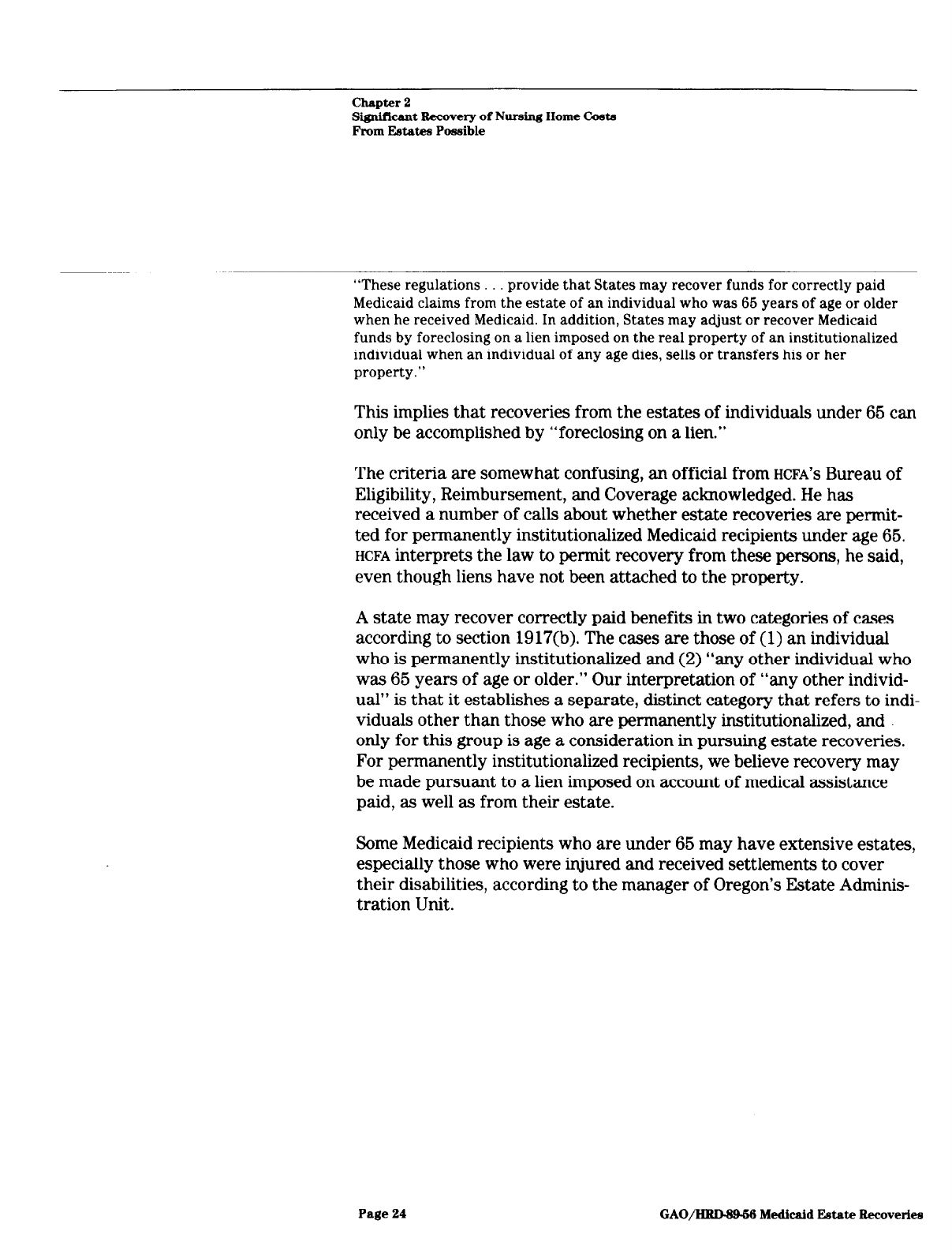

“These regulations. provide that States may recover funds for correctly paid

Medicaid claims from the estate of an individual who was 66 years of age or older

when he received Medicaid. In addition, States may adjust or recover Medicaid

funds by foreclosing on a lien imposed on the real property of an institutionalized

individual when an individual of any age dies, sells or transfers his or her

property.”

This implies

that

recoveries from the estates of individuals under 66 can

only be accomplished by “foreclosing on a lien.”

The criteria are somewhat confusing, an official from

HCFA’S

Bureau of

Eligibility, Reimbursement, and Coverage acknowledged. He has

received a number of calls about whether estate recoveries are permit-

ted for permanently institutionalized Medicaid recipients under age 66.

HCFA

interprets the law to permit recovery from these persons, he said,

even though liens have not been attached to the property.

A state may recover correctly paid benefits in two categories of cases

according to section 1917(b). The cases are those of (1) an individual

who is permanently institutionalized and (2) “any other individual who

was 66 years of age or older.” Our interpretation of “any other individ-

ual” is

that

it establishes a separate, distinct category that refers to indi-

viduals other than those who are permanently institutionalized, and

only for this group is age a consideration in pursuing estate recoveries.

For permanently institutionalized recipients, we believe recovery may

be made pursuant to a lien imposed on account of medical assistance

paid, as well as from their estate.

Some Medicaid recipients

who

are under 66 may

have

extensive estates,

especially those who were injured and received settlements to cover

their disabilities, according to the manager of Oregon’s Estate Adminis-

tration Unit.

Page 24

GAO/HRLWk% Medicaid Estate Recoverlea

Oregon Recovery Program an Example for

Other States

Although 21 states and the District of Columbia have active estate

recovery programs to recover correctly paid benefits, none has recov-

ered more per recipient than the Oregon program. Additional states are

in the process of implementing estate recovery programs. Still others,

according to the

HHS

Inspector General’s June 1988 report, are consider-

ing establishing or expanding such programs.

Despite the increasing interest in estate recovery programs,

HCFA

has lit-

tle information on them and, until recently, has provided limited techni-

cal assistance to states interested in establishing or improving a

recovery program. As a result, states have asked Oregon for technical

assistance. To get a better idea of why Oregon has been more successful

than other states in obtaining estate recoveries, we discussed with Ore-

gon officials and advocacy groups for the elderly the elements of the

Oregon program that they think are key to its success. The key elements

cited were (1) establishing enabling legislation, (2) maintaining flexibil-

ity in dealing with hardship cases, (3) securing recoveries from estates

of surviving spouses, (4) establishing a central recovery unit,

(6) appointing a conservator to handle incompetent recipients’ assets,

and (6) establishing an effective transfer-of-assets policy.

HCFA Provides

Limited Technical

Assistance

HCFA

headquarters and regional office officials have not obtained or ana-

lyzed data on estate recovery programs and, therefore, provide limited

technical assistance to states in establishing or improving recovery pro-

grams. HCFA'S

Central Office does not obtain information on the pro-

grams or take a proactive role in encouraging states to establish or

improve programs, according to an official from

HCFA'S

Bureau of Eligi-

bility, Reimbursements, and Coverage.

Similarly, officials from the five

HCFA

regional offices we visited said

that they knew which states had established recovery programs, but

lacked detailed knowledge of the scope and structure of the programs.

Although

HCFA'S

Seattle regional office conducted a study in 1986 of the

potential for estate recoveries in Idaho, the region had made no further

efforts as of December 1988 to encourage the establishment of recovery

programs.

As the implementation of the section 1917 provisions are optional,

HCFA

headquarters and regional office officials told us during the course of

our review that they do not believe it is

HCFA'S

responsibility to help,

encourage, or provide information to states regarding recovery pro-

grams. States should be on their own to set up programs and should

Page 26 GAO/HRD-SM6 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 3

Oregon Recovery Program an Example for

Other States

obtain information on successful programs from each other, the officials

said.

In commenting on a draft of this report, however,

HHS

said that it plans

to take advantage of every appropriate opportunity to encourage states

not pursuing estate recoveries, or pursuing them ineffectively, to insti-

tute effective recovery programs.

HCFA'S

May 1988 State Agency Suc-

cessful Practices Guide contains a chapter on estate recoveries profiling

five states that have successful programs,

HHS

noted. The guide was dis-

tributed to all state agency heads, Medicaid directors, third-party liabil-

ity managers, the National Conference of State Legislatures, the

National Governors’ Association, and all

HCFA

regional offices, according

to

HHS.

In addition,

HCFA

has encouraged estate recoveries and the use of

the guide in several national meetings during 1988,

HHS

stated.

Other actions taken during 1988 to improve estate recoveries include

distribution of the

HHS

Inspector General’s comprehensive study on

states’ estate recovery programs to all state Medicaid agencies and

establishment of a departmental task force to evaluate the administra-

tive and regulatory changes needed to improve states’ estate recovery

programs,

HHS

noted.

These recent actions are a step in the right direction and should help

expand estate recovery programs. The successful practices guide, how-

ever, is, in our opinion, of limited usefulness to states wishing to estab-

lish or improve estate recovery programs. Specifically, the guide

discusses few of the key elements that help account for the success of

the Oregon program, and points out ways that the five “profiled” states

could improve their programs, such as by recovering from the estates of

(1) surviving spouses and (2) recipients who were under age 66 when

admitted to the nursing home. The Inspector General’s report, in our

opinion, provides more useful guidance to states wanting to establish or

improve recovery programs.

The Recovery Process

Oregon enacted legislation in 1949 authorizing the state to recover the

in Oregon

cost of state-provided cash assistance to the elderly. In 1976, legislation

was enacted authorizing recovery of the cost of medical assistance pro-

vided to persons 66 and older. In 1986, Oregon recovered $3.7 million,

and spent about $376,000 to operate the recovery program-a benefit-

to-cost ratio of 10 to 1.

Page 26 GAO/HRD-W56 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

chapter 3

Oregon Recovery Program an Example for

Other Statea

The recovery process can be broken into three parts: (1) identifying an

applicant’s assets, (2) tracking and preserving assets while assistance is

provided, and (3) recovering from the recipient’s estate.

Identifying Applicants’

Assets

A

recovery program depends on good information to identify assets held

or transferred by public assistance recipients. Oregon’s information

gathering

process routinely begins with the caseworker at the time indi-

viduals apply for food stamps or financial, medical, or social services

assistance (see fig. 3.1). During the application process, applicants or

their representatives are asked for information on real property, bank

accounts, or other assets currently held or disposed of within 2 years of

applying for assistance.

Page 27

GAO/HRDNM6 Medicaid Estate l&cove&a

Chapter 3

Oregon Reeovery Program an Example for

Other States

Figure 3.1: Oregon’s Recovery Process:

Identifying Assets

Persons apply for public assistance, including Medicaid, at branch offices of the

state’s Department of Human Resources. As part of the process, applicants or

their representatives fill out an application asking them to identify any property

(real property, bank accounts, and other assets) the applicants own or have

recently transfened.

Caseworkers in the branch offices review the applications and determine whether

applicants are eligible. The caseworker may verify

asset

information through

contacts with

l

applicant’s bank or banks

l

county assessor’s office (real property ownership)

l

county recorder’s office (real property transfers)

The applicant/recipient is required to notify the branch office or Area Agency on

1 could affe;ibillty . 1

Aging Dfffce within 10 days of any change in income, property, and the like, that

Each year, the applicant/recipient must complete

a

redetermination of eligibility

(same form

as

an application). The caseworker uses the form to determine

whether the applicant remains eligible.

The caseworkers screen each application to make sure that the neces-

sary information is provided and to determine whether the applicant

qualifies for assistance. The caseworkers may also follow up and verify

the information provided. For example, the caseworker might

contact

the county assessor’s office

to

verify information the applicant provided

on real property ownership. The data are then sent to Oregon’s Central

Recovery Unit, which uses the information for estate recovery purposes.

Page 28

GAO/IiRDWM Medicaid Estate Recoveries

chapter 3

Oregon Recovery Program an Ebmpie

for

other State6

Tracking and Preserving

Assets

Once identified, assets should be tracked to ensure that they are being

used to pay for the recipients’ care and not being given away to others.

In Oregon, caseworkers complete a property referral form and forward

it to the central state recovery unit when they identify applicants/recip-

ients who own or have recently transferred assets (see fig. 3.2). The

form contains information on real property, mobile homes, cars, boats,

and other assets, such as trust funds that the individual owns or has

transferred. Involving the recovery unit early helps the unit to better

track applicant&/recipients’ assets. If an individual is unable to manage

his or her own affairs, the state petitions the court to appoint a conser-

vator to assist the recipient.

Page

29 GAO/liBDWM Medicaid Estate Recawerh

Chapter 3

Oregon Recovery Program an Example for

Other States

Figure 3.2:

Oregon’s Recovery

Process:

Tracking and Preserving Assets

Caseworkers in the branch offices send property referral forms to the

Department’s centralized Estate Administration Unit when applications or case

reviews show the following:

l

The applicant/recipient has real property or other assets (such as a mobile

home, car, or trust fund) that may be lost or wasted due to the applicant’s

inability to manage them or confinement to a nursing home

a

The applicant/recipient has transferred real property to someone else within

2 years of applying for assistance

l

The applicant/recipient has a situation that the caseworker is unsure how to

handle

The Estate Administration Unit takes one or more of the following actions:

l

It files the information for later use in estate recovery efforts

l

If the applicant/recipient is unable to manage his or her own financial affairs,

it petitions the court to appoint

a

conservator to do so

l

If the applicant/recipient has transferred property without adequate

compensation, it offers these options to the affected parties:

- The applicant can be paid for the transferred property

-- The property holder can give the property back

-- The new property owner can sign an “open-end” mortgage giving the state

the right to recover assistance payments from the property after the

recipient dies

-- The state can determine that the applicant/recipient is ineliyible for

assistance for a period of time based on the value of the transferred

property

l

It advises the caseworker on an appropriate course of action

1

The caseworkers and estate administrators also want to prevent appli-

cants/recipients from giving away their assets without adequate com-

pensation. When they find that applicants or recipients have given away

assets at less than fair market value within 2 years of applying for

Medicaid or at any time after applying, Oregon gives the parties

involved three options to avoid a period of ineligibility:

Page 30

GAO/llMN&W Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 3

Oregon Recovery Program an Example for

Other States

l

The applicant/recipient can be paid an adequate amount for the assets.

This would make the money received available to pay for care before

the individual could become Medicaid-eligible.

. The property holder can void the transfer and give the assets back. This

step makes the assets available to pay for care before Medicaid eligibil-

ity is established or, in the case of exempt property, available for possi-

ble recovery of costs at a later date.

. In the case of real property, the property holder can sign an “open-end

mortgage” with the state. This mortgage allows the property holder to

keep the property. But under its terms, after the Medicaid recipient dies,

the property holder pays the state (up to the value of the property) for

the cost of care provided.

If the applicant/recipient and property holder do not agree to one of the

above actions, the applicant/recipient is declared ineligible to receive

Medicaid assistance for a period of time. At the time we completed our

review, if the fair market value of the asset minus the amount of com-

pensation received by the applicant/recipient is less than or equal to

$24,000, the period of ineligibility is 24 months. Should the uncompen-

sated value exceed $24,000, the number of months the individual is inel-

igible for assistance equals the uncompensated value divided by $1,000.

For example, if property worth $30,000 was sold for $2,000, then the

uncompensated value was $28,000. The period of ineligibility would be

28 months, or $28,000 divided by $1,000.

Recovering

Provided

for Care

Recovering From Living

Recipients

A process to recover from recipients’ assets the cost of care provided is

the final step in an effective recovery program. In Oregon, recoveries

can take place while the individual is receiving assistance or after the

individual dies. In addition, Oregon law allows recovery from the

spouse’s estate if the state did not recover from the recipient’s estate.

The state may recover from living recipients for care provided. This

generally occurs when a recipient owns a home but is living in a nursing

home and is not expected to return home, the recovery unit manager

said. If the home is sold, the proceeds are used to reimburse the state for

past care provided. Any remaining assets are held in trust and used to

pay for the recipient’s present and future care. When the recipient dies,

any money not used to defray Medicaid costs remains part of the estate

to go to the recipient’s heirs, according to the manager.

Page 31 GAO/HRD-3%56 Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 3

Oregon Recovery Program an Example for

Other States

Recovering From Deceased

Recipients

The recipient may sell the home, but hold the mortgage on the home,

receiving monthly mortgage payments from the buyer. An estate admin-

istrator explained that these payments are considered income and are

used to offset the current cost of care. However, the state may recover

for the cost of care provided before the home was sold from any assets

remaining in the estate at the time of the recipient’s death.

Recipients also may assign the title of their real property to the state in

consideration for all past, present, and future care. The state then can

sell the property, and the proceeds are considered to be part of the

state’s recoveries, according to an estate administrator.

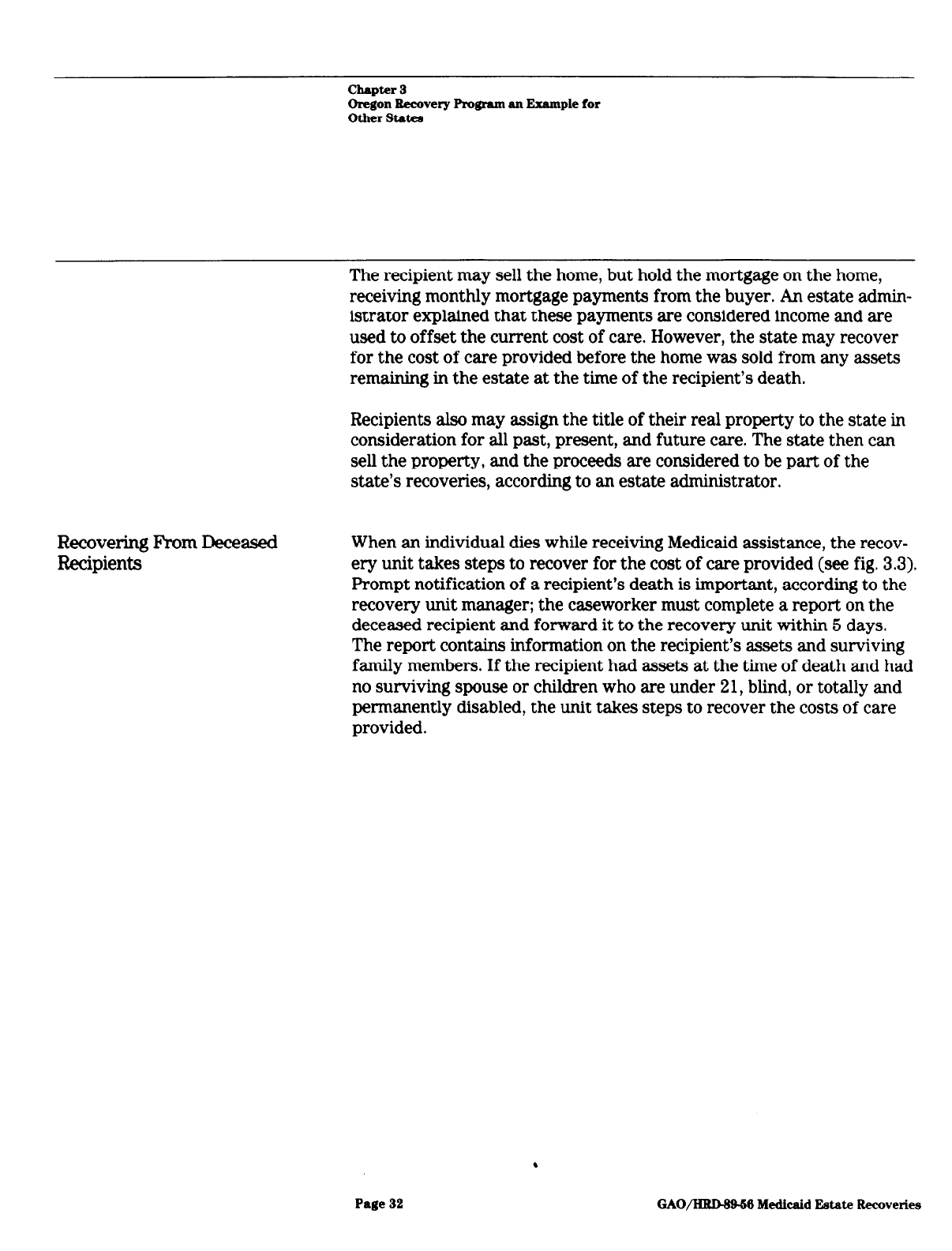

When an individual dies while receiving Medicaid assistance, the recov-

ery unit takes steps to recover for the cost of care provided (see fig. 3.3).

Prompt notification of a recipient’s death is important, according to the

recovery unit manager; the caseworker must complete a report on the

deceased recipient and forward it to the recovery unit within 5 days.

The report contains information on the recipient’s assets and surviving

family members. If the recipient had assets at the time of death and had

no surviving spouse or children who are under 2 1, blind, or totally and

permanently disabled, the unit takes steps to recover the costs of care

provided.

Page 32

GAO/ISWMBM Medicaid Estate Recoveries

Chapter 3

Oregon Remvery Program an

Example for

Other States

Recovering When Aasets Become

Available

Estates of persons on public Estates of persons not on public

assistance at the time of death assistance at the time of death

Caseworker sends a report on

deceased persons to the Estate

Administration Unit

l

notifylng the unit of

the recipient’s death

l

providing information

on available assets

l

providing information on

surviving spouse or children

If assets are available and no such

survivors remain, the Unit proceeds

If the estate is

not probated,

the Estate Ad-

ministration Unit

asks for pay-

ment from the

manager of the

estate or from

others who may

be holding the

recipient’s

assets

If the estate is

probated, the

Estate Admin-

istration Unit

files a claim

against the

estate for the

cost of care

provided

Branch offices submit monthly lists

of probate actions to the Estate

Estate Administration Unit reviews

the lists to identify deceased

persons who were

l

Former recipients. but not

receiving assistance at the

time of their death

l

Spouses of deceased recipients

Estate Administration Unit determines

whether

l

assets are available

l

the person is survived by a

spouse or by a child who is

under 21, blind, or totally

and permanently disabled.

If assets are available and no such

survivors remain, the Unit files

a

claim against the estate for

the cost of care provided.

I I

The recovery procedure the unit follows depends on

the amount

and

type of assets the recipient owned. If it appears that the estate will not

.

Page 33 GAO/HRDW56 Medicaid J2atat.e Recoveries

chapter 3

Oregon Recovery Program an JSxample

for

Other States

Recovering From Former

Recipients or Spouses

be probated because of the small value of the assets, the unit requests

reimbursement from the individual responsible for managing the recipi-

ent’s estate. Letters are also sent to the recipient’s banks and the nurs-

ing home, requesting that the recipient’s funds be forwarded to the

state. If a claim with a higher priority than medical expenses (funeral

expenses, for example) is filed against the estate, the state reimburses

the appropriate amount to the claimant from the money it receives.

If a recipient had assets of substantial value, the recovery unit asks the

recipient’s family to either repay the state for the public assistance pro-

vided (up to the value of the recipient’s assets) or probate the estate. If

the estate is probated, an estate administrator files a claim against the

estate in the county probate court for the value of the public assistance

provided. The state’s claim for public assistance would be paid from the

estate after the costs of administering the estate, the expenses of a

funeral (up to $1 ,OOO), and federal taxes are paid. The claims of heirs

are paid only after state claims are satisfied. According to Oregon’s

Estate Administration Unit, if there are sufficient assets in the estate

but no person with a higher preference is willing to become the personal

representative of the estate, the unit will petition the court to nominate

a personal representative.

Oregon also has a system to identify and recover from individuals who

received Medicaid or other assistance in the past, even if they were not

receiving assistance at the time of death. To identify these former recip

ients, the unit reviews monthly lists of probate court actions sent by

each branch office. If a former recipient is found and has no surviving

spouse or a child who is under 21, blind, or disabled, the unit calculates

the amount of public assistance and files a claim against the individual’s

estate in the probate court.

The state is also authorized to recover from the estate of a deceased

recipient’s spouse if both the recipient and the spouse are deceased and

there are no surviving children under 21, blind, or disabled. For exam-

ple, when a recipient dies but is survived by a spouse, the unit takes no

action to recover any funds at that time. Instead, the unit fills out a data

card on the spouse as a basis for later recovering from the spouse’s

estate when he or she dies. Each month, the county probate lists are

reviewed and compared with the list of spouses to see if any have died.

If there is a match, the state files a claim against the estate for public

assistance provided to the husband, wife, or both.

Page 34

GAO/HRDM-M Medicaid Estate Recoveries

-

chapter 3

Oregon Recovery Program an Example for

Other States

Key Elements of

Oregon’s Recovery

Program

There are several features of the Oregon program

that

help account for

its success and acceptance by Medicaid recipients. These elements are

discussed below.

Element 1: Oregon Enacted

Oregon enacted laws specifically authorizing

the

recovery program and

Laws Authorizing Estate

establishing the conditions under which recoveries will be authorized.

Recoveries -

Two of the states included in our review, Pennsylvania and Michigan,

said that their attempts to operate estate recovery programs administra-

tively were blocked by legal challenges. In Pennsylvania, a state attor-

ney told us that a class action suit brought against

the

state caused the

state to disband its recovery program because recovery was not permit-

ted under existing state law, and that, under section 1917, recovery was

optional, not required. Similarly, Michigan discontinued its estate recov-

ery program because of a binding opinion issued by the state’s Attorney

General concluding that the state could not recover because state laws