In collaboration with

EY Family

Ofce Guide

Pathway to successful family and

wealth management

Family ofce services

Contents

1EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Contents

About us 02

Foreword 03

Introduction 04

What is a family ofce?

Section 06

1 Why set up a family ofce? 06

2 Family ofce services 09

3 The costs of running a family ofce 20

4 Family ofce governance 22

5 Constructing a business plan, stafng and strategic planning 26

6 Risk management 32

7 The investment process 35

8 IT, trading tools and platforms 41

Appendix 44

1 The legal setup (excluding the US) 44

2 US regulatory and tax considerations 60

Contributors 66

References 68

Contact us 70

2 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

About our

research partners

Credit Suisse

Credit Suisse AG is one of the world’s leading nancial

services providers and is part of the Credit Suisse group

of companies (referred to here as “Credit Suisse”). As an

integrated bank, Credit Suisse is able to offer clients its

expertise on the issues of private banking, investment

banking and asset management from a single source.

Credit Suisse provides specialist advisory services,

comprehensive solutions and innovative products to

companies, institutional clients and high net worth

private clients worldwide, and also to retail clients in

Switzerland. Credit Suisse is headquartered in Zurich

and operates in over 50 countries worldwide. The group

employs approximately 46,300 people. The registered

shares (CSGN) of Credit Suisse’s parent company, Credit

Suisse Group AG, are listed in Switzerland and, in the

form of American Depositary Shares (CS), in New York.

Further information about Credit Suisse can be found at

www.credit-suisse.com.

The Center for Family Business —

University of St. Gallen

The Center for Family Business of the University of

St. Gallen (CFB-HSG) focuses on research, teaching, and

executive education in the context of family rms and at

international level.

The CFB-HSG’s work involves initiating, managing,

promoting and running training and transfer programs,

research projects and courses.

At the St. Gallen Family Ofce Forum, representatives of

German-speaking single family ofces meet twice a year

in a discrete and trustful setting. The aim is an intensive

exchange of experiences, best practice, and ideas.

www.cfb.unisg.ch

About us

EY Global Family Business

Center of Excellence

EY is a market leader in advising, guiding and recognizing

family businesses. With almost a century of experience

supporting the world’s most entrepreneurial and

innovative family rms, we understand the unique

challenges they face — and how to address them.

Through our EY Global Family Business Center of

Excellence, we offer a personalized range of services

aimed at the specic needs of each individual

family business — helping them to grow and succeed

for generations.

The Center, the rst of its kind, is also a powerful resource

that provides access to our knowledge, insights and

experience through an unparalleled global network of

partners dedicated to help family businesses succeed

wherever they are.

For further information, please visit ey.com/familybusiness.

EY Family Ofce Services

Our services for families and family ofces are a reection

of our broad range of expertise and a symbol of our

commitment toward family businesses around the world.

Our comprehensive and integrated approach helps

families to structure their wealth and preserve it for

future generations. Our goal is to unlock the development

potential of the family through a multidisciplinary

approach that scrutinizes operational, regulatory, tax,

legal, strategic and family-related aspects.

For more information about the full range of our family

ofce services, please visit ey.com/familyofce.

3EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Dear Reader,

It gives us great pleasure to bring to you our 2016 revised edition of the EY Family

OfceGuide.

In the last decade or so, we have seen a distinct acceleration in the establishment of

family ofces around the world and even more so in the emerging markets. However,

irrespective of geography, there’s a certain consistency to the motivations behind setting

up a family ofce. Mitigating family conicts, preserving family wealth and ensuring its

inter-generational transfer, consolidating assets, dealing with a sudden liquidity inux, and

increasing wealth management efciency are some of them.

Another reason for the emergence of family ofces is families’ desire to have greater

control over their investments and duciary affairs while reducing complexity. This need

for a higher degree of control was partly provoked by the nancial crisis, in the aftermath

of which wealthy families wanted to ease their concerns about dealing with a wide range of

external products and service providers.

Family ofces are rather complicated structures, neither easy to understand nor simple to

implement. This publication will offer a step-by-step process that aims to demystify what’s

involved in setting up and running family ofces.

This revised edition of the guide, which was rst published in 2013, is certainly one of

the most comprehensive and in-depth ever published. It is designed as a learning tool to

provide guidance to families considering setting up a family ofce. They include business

families who wish to separate their family wealth and assets from the operating business,

and successful entrepreneurs looking to structure the liquidity gained from a highly

protable sale in order to further grow and preserve their wealth. It is also a useful guide on

the current leading practices for those who already have a family ofce.

While compiling this report, EY worked extensively with Credit Suisse, the University of

St. Gallen, and family ofces themselves. All these organizations and individuals have

provided invaluable insights into family ofces and their concerns, and the report would

not have been possible without their help.

We hope that you will nd this report helpful and illuminating for your decision-making as

you plan the path for your family into the future.

Foreword

Marnix Van Rij

Global Leader

EY Family Business

Peter Brock

Family Ofce Services

Leader, Germany,

Switzerland and Austria

Richard Boyce

Family Ofce Services

Leader, Asia-Pacic

Robert (Bobby) A. Stover

Family Ofce Services

Leader, Americas

4 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Introduction

What is a family ofce?

Family ofces have their roots in the sixth century, when a king’s

steward was responsible for managing royal wealth. Later on, the

aristocracy also called on this service from the steward, creating

the concept of stewardship that still exists today. But the modern

concept of the family ofce developed in the 19th century. In

1838, the family of nancier and art collector J.P. Morgan founded

the House of Morgan to manage the family assets. In 1882, the

Rockefellers founded their own family ofce, which is still in

existence and provides services to other families.

1

Although each family ofce is unique to some extent and varies

with the individual needs and objectives of the family it is devoted

to (Daniell and Hamilton, 2010), it can be characterized as a

family-owned organization that manages private wealth and

other family affairs.

Over the years, various types of family ofces have emerged.

The most prominent ones are the single family ofce (SFO) and

the multifamily ofce (MFO), but there are also embedded family

ofces (EFOs) linked to the family business, where there is a low

level of separation between the family and its assets. The SFOs

and MFOs are distinct legal entities and manage assets that are

completely separated from the family or the family business.

With the progressive growth of the family tree — owing to the birth

of children and grandchildren and the addition of in-laws — and

an increase in the complexity of the family’s asset base, families

usually professionalize their private wealth management by setting

up SFOs. As subsequent generations evolve, and branches of

the family become more independent of each other, investment

activities within the original SFO activities become separated. This

is the cornerstone for the emergence of an MFO. Sometimes these

ofces open up their services to a few non-related families.

Since the individual services of a family ofce are tailored to the

clients, or the family, and are correspondingly costly, the amount of

family wealth under management is generally at least US$200m. It

is more revealing, however, to calculate the minimum wealth under

management in the light of return expectations and targets, and

the resulting costs of the family ofce. This shows that there is no

clear lower limit for a family ofce. The costs of the family ofce,

plus the return target, must be achievable with the chosen asset

allocation and structure.

1. For more information see

rockefellernancial.com.

5EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Family ofces are arguably the fastest-growing investment

vehicles in the world today, as families with substantial wealth are

increasingly seeing the virtue of setting one up. It is difcult to

estimate how many family ofces there are in the world, because of

the various denitions of what constitutes a family ofce, but there

are at least 10,000 single family ofces in existence globally and at

least half of these were set up in the last 15 years.

The increasing concentration of wealth held by very wealthy

families and rising globalization are fueling their growth.

Particularly important in the years ahead will be the strong growth

of family ofces in emerging markets, where for the most part

they have yet to take hold — despite the plethora of large family

businesses in these economies.

2

This report attempts to dene the family ofce in authoritative

detail. It looks at issues such as the reasons for setting up a family

ofce; key stafng concerns; which services a family ofce should

cover and which should be outsourced; how to optimize investment

functions and to ensure they work for the benet of the family. The

report also looks at regulatory and tax issues in key markets, which

anyone considering setting up a family ofce needs to know. It also

addresses the relationship between the family and the external

professionals who are brought in to run a family ofce. It is crucial

for a family ofce to establish a balance between these two groups

if it is to function well.

Family ofces are complex organizations that require deep

knowledge — not just of investment variables, but also a host

of other factors. This guide is a detailed handbook for those

planning to set up a family ofce and also for those looking to set

benchmarks of leading practice within their existing family ofce.

As wealth grows, particularly

in the emerging markets, there

is no doubt that family ofces

will play an even bigger role in

the management of substantial

wealth in the years ahead.

2. CreditSuisseWealth

Report2015

6 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Section

1Why set up a family ofce?

As concerns about wealth preservation and succession planning

within family businesses continue to rise, wealthy families are

increasingly evaluating the benets of setting up a family ofce.

The reasons why

There are many reasons why setting up a family ofce makes

sense, but at the root of these is the desire to ensure smooth

intergenerational transfer of wealth and reduce intrafamily disputes.

This desire inevitably increases from one generation to the next,

as the complexity of managing the family’s wealth grows. Without

being exhaustive, the following points set out the reasons why a

family ofce makes sense:

• Privacy and condentiality

For many families, the most important aspect of handling of

their private wealth is privacy and the highest possible level of

condentiality. The family ofce often is, and should be, the

only entity that keeps all the information for all family members,

covering the entire portfolio of assets and general personal

information.

• Governance and management structure

A family ofce can provide governance and management

structures that can deal with the complexities of the family’s

wealth transparently, helping the family to avoid future conicts.

At the same time, condentiality is ensured under the family

ofce structure, as wealth management and other advisory

services for the family members are under a single entity owned

by the family.

• Alignment of interest

A family ofce structure also ensures that there is a better

alignment of interest between nancial advisors and the family.

Such an alignment is questionable in a non-family ofce structure

where multiple advisors work with multiple family members.

• Potential higher returns

Through the centralization and professionalization of asset

management activities, family ofces may be more likely to

achieve higher returns, or lower risk, from their investment

decisions. Family ofces can also help formalize the

investment process, and maximize investment returns for all

family members.

7EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

• Separation

Family ofces allow for separation, or at least a distinction, between

the family business and the family’s wealth or surplus holdings.

• Risk management

Family ofces allow for operational consolidation of risk,

performance management and reporting. This helps the advisor

and principals to make more effective decisions to meet the

family’s investment objectives.

• Centralization of other services

Family ofces can also coordinate other professional services,

including philanthropy, tax and estate planning, family

governance, communications and education, to meet the

family’s mission and goals.

• Focal point for the family

In cases where the main family business has been sold, a family

ofce can offer a new focal point of identication for the family

members, for example when the family ofce manages the

philanthropic activities of the family.

Why might there be doubts about setting up a

family ofce?

The establishment of a family ofce is a big undertaking, and there

have been cases when family ofces have not met the family’s

expectations. Some of the potential doubts and concerns about

setting up a family ofce are:

• Cost

The cost of regulatory and compliance reporting remains high,

which means that the level of assets under management that a

family ofce needs to underpin must be sufcient to offset its

xed costs.

• Market, legal and tax infrastructures

Family ofces function better when operating from centers where

there are sophisticated markets and legal and tax structures.

The absence of these in emerging markets has undermined the

development of family ofces there. This has often meant that

there has been little connection between the huge level of wealth

in some emerging markets and the number of family ofces.

Much of the wealth in emerging markets is still controlled by

the rst generation. This has also inhibited the growth of family

ofces, because many are launched during a wealth transition

from one generation to the next.

Main types of family ofces

Embedded Family Ofce (EFO)

An EFO is usually an informal structure that exists within

a business owned by an individual, or family. The family

considers private assets as part of their family business and

therefore allocates private wealth management to trusted

and loyal employees of the family business. Usually the

chief nance ofcer (CFO) of the family business and his

department’s employees are entrusted with the family ofce

duties. As not necessarily the most efcient of structures,

more and more entrepreneurial families are separating their

private from their business wealth and are considering taking

the family ofce functions outside the family business, not

least for reasons of privacy and tax compliance.

Single Family Ofce (SFO)

An SFO is a separate legal entity serving one family only.

There are a number of reasons for setting up an SFO:

• The retirement of the business-owning generation

• A greater desire to diversify and widen the asset structure

beyond the focal family rm

• A rising exposure to non-investment risks, such as privacy

concerns and legal risks

The family owns and controls the ofce that provides

dedicated and tailored services in accordance with the needs

of the family members. Typically, a fully functional SFO will

engage in all, or part of, the investments, duciary trusts

and estate management of a family; many will also have a

concierge function.

Multifamily ofce (MFO)

A multifamily ofce will manage the nancial affairs of

multiple families, who are not necessarily connected to each

other. As with an SFO, an MFO might also manage the

duciary, trusts and estate business of multiple families as

well as their investments. Some will also provide concierge

services. Most MFOs are commercial, as they sell their

services to other families. A very few are private MFOs,

whereby they are exclusive to a few families, but not open

to other families. Over time, SFOs often become MFOs.

This transition is often due to the success of the SFO,

prompting other families to push for access. Economies

of scale are also often easier to achieve through an MFO

structure, promoting some families to accept other families

into their family ofce structure.

• The MFO offering

To address the problem of the high operating costs of a family

ofce, families often set up MFOs, in which several families pool

their wealth together. Often these MFOs will be directed by the

“lead” family that initiated the ofce. In MFOs, all assets are

managed under one umbrella. But MFOs typically cater for a

range of family size, wealth and maturity levels. This means that

families can run the risk of not receiving the personalized advice

that they would have done in a dedicated family ofce setup.

When considering establishing a family ofce, some can see

potential positives as negatives. This tends to be particularly

prevalent in the following cases:

• The preference for privacy

Some families may be hesitant about consolidating their wealth

information through a centralized family ofce structure.

• Trust of external managers

Setting up a family ofce is typically contingent on the level of

trust and comfort families have with external asset managers.

However, trust typically stems from long-standing relationships

with external managers.

• Expectations on returns

Ultimately, family ofces rely on their longevity through

ensuring wealth preservation. This difculty of securing market

returns in recent years has led to some tension in this respect.

Furthermore, during generational transitions, family ofce

structures are tested, often to the point of destruction, as the

next generation presses for different goals and objectives to

manage the family’s wealth.

8 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Section

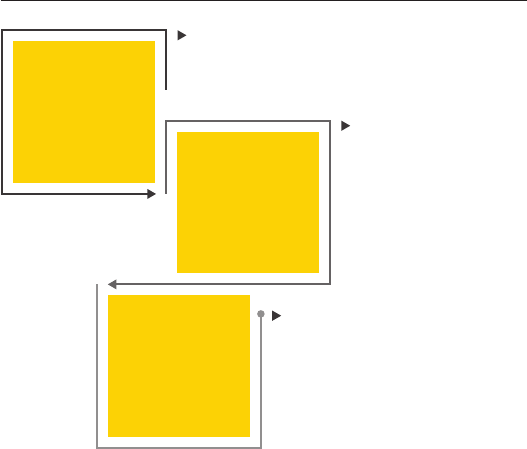

At the heart of any family ofce is investment management, but

a fully developed family ofce can provide a number of other

services, ranging from training and education to ensuring that

best practice is followed in family governance. This section looks

at the full range of services a mature family ofce could potentially

provide (see gure 2.1). These include:

Financial planning

Investment management services

Typically, this will be the main reason for setting up a family ofce,

as it is central to ensuring wealth preservation. These services

will include:

• Evaluation of the overall nancial situation

• Determining the investment objectives and philosophy of

the family

• Determining risk proles and investment horizons

• Asset allocation — determining mix between capital market and

non-capital market investing

• Supporting banking relationships

• Managing liquidity for the family

• Providing due diligence on investments and external managers

Philanthropic management

An increasingly important part of the role of a family ofce

is managing its philanthropic efforts. This will include the

establishment and management of a foundation, and advice

on donating to charitable causes. These services would

typically involve:

• Philanthropic planning and strategy

• Assistance with establishment and administration of charitable

institutions

• Guidance in planning a donation strategy

• Advice on technical and operational management of charities

9EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Section

2Family ofce services

• Formation of grant-making foundations and trusts

• Organizing charitable activities and related due diligence

Life management and budgeting

Some of these services are typically dened as “concierge” in

nature, but they are broader in scope, inasmuch as they also

include budgeting services. Services under this heading will include:

• Club (golf, private, etc.) memberships

• Management of holiday properties, private jets and yachts

• Budget services, including wealth reviews, analysis of

short- and medium-term liquidity requirements and

long-term objectives

Strategy

Business and nancial advisory

Beyond the asset management advisory, family ofces will also

provide advisory services on nancing and business promotion.

These will include:

• Debt syndication

• Promoter nancing

• Bridge nancing

• Structured nancing

• Private equity

• Mergers and acquisitions

• Management buyouts

• Business development

Estate and wealth transfer

Family ofces will be involved in business succession and legacy

planning, enabling the transfer of wealth to the next generation.

These services will include:

• Wealth protection, transfer analysis and planning related to

management of all types of assets and income sources

• Customized services for estate settlement and administration

• Professional guidance on family governance

• Professional guidance regarding wealth transfer to succeeding

generations

Training and education

Much of this revolves around the education of the next generation

on issues such as wealth management and nancial literacy, as well

as wider economic matters. These services will include:

• Organizing family meetings

• Ensuring family education commitments

• Coordination of generational education with outside advisors

Governance

Reporting and record keeping

The maintenance of records and ensuring there is a strong

reporting culture is another core part of a family ofce’s services.

Key to these services is:

• Consolidating and reporting all family assets

• Consolidating performance reporting

• Benchmark analysis

• Annual performance reporting

• Maintaining an online reporting system

• Tax preparation and reporting

Administrative services

Administrative services, or back-ofce services, are essential to the

smooth running of a family ofce. These services will include:

• Support on general legal issues

• Payment of invoices and taxes, and arranging tax compliance

• Bill payment and review of expenses for authorization

• Opening bank accounts

10 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

• Bank statement reconciliation

• Employee management and benets

• Legal referrals and management of legal rms

• Public relations referrals and management of public relations rms

• Technology systems referrals and management of these vendors

• Compliance and control management

Succession planning

Ensuring a smooth succession and planning for future generations

is integral to the long-term viability of the family ofce and the

family it serves. These services will include:

• Continuity planning relating to unanticipated disruptions in

client leadership

• Evaluation of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and

threats (SWOT analysis) of senior executives both within and

outside the family

• Re-evaluation of family board regarding roles of

non-family directors

• Structuring of corporate social responsibility platforms and

programs

• Development of formal knowledge sharing and

training programs

• Implementation of intergenerational estate transfer plans

• Adoption of a family charter or constitution, specically aiming to:

1. Formalize the agreed structure and mission of the

family business

2. Dene roles and responsibilities of family and

non-family members

3. Develop policies and procedures in line with family values

and goals

4. Determine process to resolve critical business-related

family disputes

Advisory

Tax and legal advisory

Tax, in particular, has become a much more important issue for

family ofces in recent years and as such has assumed a more

important part of the functions of a family ofce. Legal matters

are also important. A family ofce will typically employ a general

counsel and/or a chartered or certied accountant, or several

accountants and tax experts. These professionals usually provide

the following services:

• Construct a tax plan that best suits the family

• Design investment and estate planning strategies that take into

account both investment and non-investment income sources and

their tax implications

• Ensure all parts of the family ofce are tax compliant

Compliance and regulatory assistance

Family ofces need to ensure strict compliance with regulations

pertaining to investments, assets and business operations. These

services will include:

• Providing auditing services for internal issues

• Establishing a corporate governance mechanism

• Ensuring a high level of staff hiring

• Group performance monitoring and compliance

• Offering recommendations on independent and board advisory

formation

• Strengthening the regulatory investment process

11EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

12 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Risk management and

insurance services

This is a service that has assumed a more

important role in recent years because

of the nancial crisis of 2008–09 and

the subsequent fallout. It will be a crucial

service for family ofces in the future as

well. These services will include:

• Risk analysis, measurement and

reporting

• Assessment of insurance requirements,

policy acquisition and monitoring

• Evaluation of existing policies and

titling of assets

• Evaluation of security options for clients

and property

• Formulation of disaster recovery

options and plans

• Protection of assets, which could involve

the use of offshore accounts

• Development of strategies to ensure

hedging of concentrated investment

positions

• Physical security of the family

• Data security and condentiality

• Review of social media policy

and development of reputation

management strategy

Figure 2.1. Family ofce services

A

d

v

i

s

o

r

y

F

i

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

p

l

a

n

n

i

n

g

G

o

v

e

r

n

a

n

c

e

S

t

r

a

t

e

g

y

Family

Office

Services

T

a

x

a

n

d

l

e

g

a

l

C

o

m

p

l

i

a

n

c

e

R

i

s

k

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

L

i

f

e

P

h

i

l

a

n

t

h

r

o

p

i

c

I

n

v

e

s

t

m

e

n

t

a

d

v

i

s

o

r

y

a

n

d

r

e

g

u

l

a

t

o

r

y

a

n

d

i

n

s

u

r

a

n

c

e

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

m

a

n

a

g

e

m

e

n

t

a

s

s

i

s

t

a

n

c

e

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

a

n

d

b

u

d

g

e

t

i

n

g

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

k

e

e

p

i

n

g

p

l

a

n

n

i

n

g

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

a

n

d

r

e

c

o

r

d

S

u

c

c

e

s

s

i

o

n

A

d

m

i

n

i

s

t

r

a

t

i

v

e

R

e

p

o

r

t

i

n

g

a

d

v

i

s

o

r

y

t

r

a

n

s

f

e

r

e

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

fi

n

a

n

c

i

a

l

a

n

d

w

e

a

l

t

h

a

n

d

B

u

s

i

n

e

s

s

E

s

t

a

t

e

T

r

a

i

n

i

n

g

13EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Determining servicing priorities: the

make-or-buy dilemma

Even the largest family ofce, in terms of assets under

management, will need to assess whether or not to outsource

services. Outsourcing certain services can be benecial from a

cost efciency and know-how perspective, offering advantages to

family ofces that include:

• Reduced costs and overheads, and improved staff productivity

• Economies of scale, particularly for high-value professional

services, thus enabling lower prices for related services

• The benets of objective advice from experienced professionals

who possess specialized skills

• Help with defending the family ofce’s regulatory independence

when outsourcing investment management, by allowing

investment decisions to be made by external providers

• Due diligence and continuous monitoring can be carried out by

the directors of the family ofce to ensure performance and

security against risk

On the other hand, a number of key services are usually kept

in-house. The advantages of this are mostly related to condentiality

and the independence of the family ofce, and include:

• Higher levels of condentiality and privacy

• Assurance of independent and trusted advice

• Consolidated management of family wealth

• Development of skills specically tailored to the family’s needs

• Greater and more direct family control over its wealth

• Keeping investment knowledge within the family

• Assurance of optimal goal agreement, along with the avoidance

of conicts of interest with external providers

Given these considerations, it is crucial to obtain the right balance

and to identify those services best suited for management in-house.

Many factors involved in the make-or-buy decision are specic to

the setup chosen for the family ofce, in particular:

• The size of the family and how many family members want to use

the family ofce

• The net worth and complexity of the family wealth

• The family’s geographical spread

• The variety of assets, both liquid and illiquid, under

management

• The existence of a family business and the link between this and

private wealth management

• The skills and qualications of family members

• The importance of condentiality and privacy

• The consideration of whether the family ofce should be a cost

or a prot center

This variety of factors highlights how vitally important it is for

the family to clearly determine its expectations and address key

questions prior to creating the business plan for the family ofce.

These include priority setting and scope denition for the services

to be offered from the family ofce:

• Who should be the beneciaries of the family ofce and what

is the overall strategy of the family to secure and expand its

wealth over generations?

• Is the family’s priority traditional asset management of liquid

funds, with or without a portfolio of direct entrepreneurial

investments? And where does philanthropy t into the

mix, if at all?

• Should the family ofce act as the asset manager for all family

members, or should it just be an advisor for some specic

services to selected family members?

• Is the family ofce’s core task that of a nancial advisor, or

more that of an educational facilitator for the next generation

of family members?

• What services should the family ofce offer from the range of

asset management tasks, controlling and risk management, tax

and legal advice to concierge services and educating the next

generation?

Although the make-or-buy decision must be based on the specic

setup of the family ofce, some general considerations can help

to determine the optimal solution. Best practice is based on the

goal of obtaining the most effective services in an efcient way

and avoiding potential operational risks.

14 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Table 2.1. Key determinants of the make-or-buy decision

Cost and budget

Escalating costs can pose a serious challenge to family ofces. Clearly, it is unreasonable to insource the whole range of potential

services without considering the economic benets. Appointing an outside provider can ensure quality, and possibly cost savings, as the

family ofce would benet from economies of scale.

Expertise

The priority services as dened by the family will most likely be covered in-house in order to ensure independent expert advice to the

family. However, the family ofce will gain from outsourcing certain selected services that require specic expertise.

Regulatory restrictions

A family ofce should consider all regulations, depending on its distinct legal structure. While SFOs are signicantly less regulated, as

they deal with issues within the family, MFOs often fall under specic regulatory regimes. In the absence of professional management, a

family ofce runs the risk of serious fallout from negative publicity. Legal action could also be costly and harmful to reputations.

Technology and infrastructure

The technology employed by an external provider can serve the family ofce effectively. Buying in these services has become even

more of a priority as nancial operations become more complex.

Complexity

If the family’s assets are substantial and complex, the family ofce will have to hire more staff or outsource services. At the same

time, the in-house decisions on all matters have to be nal — so internal staff have to maintain the ultimate overview and

decision-making process.

Data condentiality

If condentiality is a prerequisite, then services where this is a priority should be brought in-house. Non-critical systems and

infrastructure can be outsourced.

The traditional model

Typically, nancial planning services, asset allocation, risk

management, manager selection, and nancial accounting and

reporting services tend to be provided in-house. Global custody,

alternative investments and private equity, and tax and legal

services are often outsourced.

However, families should be aware that the greater the level of

outsourcing, the less direct inuence the family will have over

the decision-making process within the family ofce, and the less

exclusive the products and services will be. Table 2.2 provides

an overview of selected family ofce services, which can be

categorized as in-house or outsourced based on market analysis.

Table 2.2. Family ofce services: in-house or outsourced

Type of service Service category In-house Outsourced

Investment management

and asset allocation

Financial planning Basic nancial planning and asset allocation decisions

should be provided in-house

The more complex, specialized and diverse assets

make outsourcing a practical option

Tax and legal advisory

Advisory Selectively done in-house Often outsourced to a trusted advisor to ensure

state-of-the-art quality of service

Reporting and record

keeping

Governance Record keeping and documentation demand condentiality

and so this should ideally be done in-house

Basic reporting tools and software may be provided

externally

Philanthropic

management

Financial planning In-house expertise should serve to assist with

philanthropic activities

Setting up a foundation and related activities often

outsourced to a consultancy

15EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Type of service Service category In-house Outsourced

Compliance and

regulatory assistance

Advisory Size of family ofce might require full-time legal and

accountancy expertise

Full-time legal staff will be an unnecessary and costly

addition to family ofces, which are not large enough

to require them, so can be outsourced when needed

Risk management and

insurance services

Advisory Some risk management skills should be provided in-house,

in order to ensure ultimate peace of mind

Can be outsourced, as external risk and insurance

professionals can offer trusted expert advice

Life management and

budgeting

Financial planning Should be done in-house if information condentiality is

a priority

Only specialized services would tend to be brought

in-house, less specialized services can be outsourced

Training and education

Strategy Can be done in-house, as identifying suitable options for

education is by its nature an internal process

Can be outsourced if expert opinion on higher

education is required for training and development

Business advisory

Strategy Often the general counsel or the nance director of the

family business is involved in the setup of the family ofce

The services of an external expert can offer a

competitive edge

Estate and wealth

transfer

Strategy In-house expertise is required as data condentiality is

vital

The family can consult external legal advisors for

procedural and legal issues

Administrative services

Governance Administrative services require daily monitoring and so

can be done in-house

Outsourcing could lead to greater costs

Succession planning

Governance Clarifying level of interest of next generation members

with regard to the business and family ofce

Education, objective assessment of managerial skill,

and denition of entry path of next generation family

members

Benets of in-house

• Highest level of condentiality and privacy

• Independent and trusted advice to the family is ensured

• Total and consolidated management of family wealth

• Family ofce can develop distinct skills, specically tailored to the

family’s needs

• Greater and more direct family control over its wealth

• Keeps investment knowledge within the family

• Ensures optimal goal agreement and avoids any conicts of

interest with external providers

Benets of outsourcing

• Helps a family ofce reduce costs and overheads, helps with staff

productivity

• Helps deliver economies of scale, particularly when it comes to

high-value professional services, thus enabling lower prices for

related services

• Offers the benet of objective advice from experienced

professionals who possess specialized skills

• Outsourcing investment management may help a family ofce

defend its regulatory independence by allowing investment

decisions to be made by external providers

• Suggests less direct control, which implies due diligence and

continuous monitoring can be carried out by the directors of the

family ofce to ensure performance and security against risk

16 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Philanthropy: moving from giving to creating impact

The world, and the challenges it faces, are changing rapidly.

Growing inequality, the forces of climate change, rapid urbanization

and resource scarcity are increasingly putting pressure on the

world’s most vulnerable people, both at home and abroad.

1

We

need new strategies to meet these challenges — strategies that

involve a fundamental rethink of the nature of philanthropy.

Traditional paradigms of philanthropy are evolving. With a

focus on creating impact, they are becoming more accessible,

sustainable and effective. Reective of the social and technological

changes happening around the planet, this evolution reminds

us that, in a globalized world, small groups of people can have

profound impacts.

Philanthropy is one of the most rewarding, and distinctively

different, activities that can be undertaken from a family ofce.

As with all family ofce activities, philanthropy too deserves to

be conducted with total professionalism and commitment. Its

challenges and rewards should be acknowledged.

It has also been found that philanthropy is an integral component

of many wealthy families’ lives. For example, America’s 50 most

generous donors increased their giving by 33% last year.

2

There

has also been a rise in the number of technological entrepreneurs

under 40 using their wealth to engage in philanthropic work.

While some of the trends in philanthropy are changing, the level of

commitment to give back to society and create a positive impact

remains the same.

How can a family ofce help the family achieve its

philanthropic goals?

One common question facing family ofces and family members is

how to structure philanthropic endeavors to achieve tax, economic

and long-term charitable goals. Many families see philanthropy

as a way to not only make a lasting impact on their communities,

their countries, or the world, but also as a way to connect with and

guide the principles that will impact the multiple generations that

have either beneted or may benet from the family wealth. The

form of charitable giving may vary from a direct gift to a charitable

organization to a donation to a charitable vehicle (discussed below)

established by the family for ongoing philanthropic activities.

Philanthropy as a way to guide future generations

Many families view philanthropy as a long-term mission that is

critical to teaching future generations responsibility and the impact

wealth can have on society. They believe philanthropy can teach

younger family members valuable life and business skills, enabling

them to develop their passions and nd fullment in working for

something they believe in. In some of these families, the future

generations will even get to decide which charities should receive

benets, how much and for how long.

A family ofce should memorialize the family’s philanthropic goals

in the family mission statement or the family constitution. It should

make sure the charities qualify for tax-exempt status and that

charitable pledges are fullled in a timely manner. It is the family

ofce that will likely be involved in deciding which assets to donate

to charity. In the US, for example, the type of asset donated can

impact the amount of the eligible deduction as well as the potential

yearly deduction limitations.

Philanthropy through investment choices

Wealthy families have made substantial charitable donations

in recent years. There is also a trend for families to align their

investment choices to their charitable motives. Families are

increasingly making investments that can be categorized as impact

investing or socially responsible investing. Both of these strategies

seek to further philanthropic goals on the basis of how, and in which

companies, the family invests.

Impact investing seeks to make a difference to communities by

choosing to invest in companies that align prots with charitable

intentions. For example, a family may decide to invest in a

company that will produce methods to purify water in economically

challenged regions.

1. EYMegatrends2015

2. “The 2015 Philanthropy 50”, The Chronicle of Philanthropy

Philanthropy

17EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Socially responsible investing seeks to maximize delivery of

philanthropic goals, even at the cost of potentially higher returns.

An example of socially responsible investing may be divesting your

portfolio of all shares of Company X stock if they are producing

goods in a manner that is not environmentally safe or if their

chairperson makes a public statement on a position that the family

does not agree with.

Family identication with philanthropy can be a means of honoring

the family’s founder. It can be a vehicle for nding new roles for

family members — including those who might feel that their skills

and interests may not lie in the family business. A systematic

program of philanthropy can be both a shield (offering a proper

process for responding to the many unsolicited and perhaps

inappropriate requests for funds commonly received by high-prole

families) and a sword (enabling the family to have a signicant

positive impact on an issue of concern to it). Most importantly,

philanthropy can provide a family with at least one notable

commonality — acting as “the glue that holds the family together” —

especially as a family increases in size and diversity.

Philanthropy can expand a family ofce’s networks, add skills,

generate employee satisfaction, and offer new and post-career

options. Family ofce or business involvement in philanthropy

can be a tangible demonstration of corporate citizenship and can

enhance the prole of the family.

Denition and change over time

The goal of philanthropy has always remained the same, to promote

the welfare of society and to increase the business’s public value.

However, the means of achieving this goal have undergone rapid

transformation.

Traditional notions of philanthropy emphasized doing good through

donations or through the establishment of charitable foundations.

This approach, born of social obligation, was free from the

expectations of measurable impact, accountability, transparency

and direction. In this traditional approach, philanthropy was also

seen as exclusive — only accessible to those with enough money to

give away — or organized through religious or political institutions

with specic interests and agendas.

Modern philanthropy, however, is decidedly different. Today’s

philanthropists use innovative solutions to solve specic problems,

with approaches that are targeted and selective, and impacts and

outcomes that are measurable. Philanthropy is also not seen as

exclusive anymore. Now, philanthropists come from a wide range of

ages and backgrounds, ranging from individuals and businesses to

NGOs and not-for-prots, all of whom are brought together by one

common goal, to help fellow human beings.

Leading practices — the building blocks of an

effective, family ofce-based philanthropy

Creating an effective, ofce-based philanthropic program requires

decisions to be made on matters such as:

• Should there be a mission statement for the philanthropic

strategy?

• Should the overall program be thematic or general and, if

thematic, what should the priority issues be?

• What should the geographic reach of the program be?

• Should the program be proactive (programs to be funded and

initiated by the ofce) or reactive (inviting applications from the

community)?

• Will the funding be short-term or long-term?

• Will funding be directed at projects or general organizational

support?

• Should there be a few large grants or several smaller grants?

• Should there be public guidelines and an annual report?

• What should the internal decision-making process be?

• How will the directors be chosen and what succession

arrangements should be made?

• What is the role of non-family members as professionals and

directors?

• Are professional advisors involved and is the philanthropic

strategy carried out professionally to optimize tax and legal

implications?

18 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

• Will collaboration with other funders be sought in order to gain

the benets of collective impact?

• What priority should be given to impact and public value

assessment, and by what means?

• Is there an investment charter to direct the length, asset type and

risk of the corpus funds?

These are only some of the matters to be considered and only a few

of these questions can have simple right or wrong answers. It is the

nature of the philanthropic sector that much remains ambiguous

and subject to different approaches. This, however, makes it all the

more important that the commitment to, culture of, and processes

for, reective and systematic philanthropic practice be in place

in a family ofce. Fortunately, the philanthropic sector is rich in

accessible and helpful written resources, and personnel who are

willing to advise, collaborate and share.

Top trends

1

2

3

4

Seeking to align

their established

philanthropic

activities with

strategy and values

Looking for

strategic direction

with their

philanthropic

activities

Evaluate impact of

established

philanthropic

portfolios

High-impact

philanthropic

investment

Creating societal

value and addressing

complex challenges

19EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

There are a number of global trends shaping the modern

philanthropic landscape.

The role of technology

Technology has impacted every aspect of modern philanthropy.

The internet has given people access to a wealth of information

on virtually every topic imaginable. This power not only enables

light to be shined on otherwise ignored topics, but also provides

access to the information needed to make contributions. While

modern technology enhances the ability to form local and global

partnerships more effectively, it also ensures that in some small

measure, any individual can be a philanthropist.

Socially conscious businesses

Philanthropy is increasingly seen as core to modern businesses’

operations, crucial to their social license to operate and enhanced

by the entrepreneurial spirit. Modern philanthropic activities take

many forms, including donations, charitable projects and social

ventures. However, they can also take a sustainable and protable

form, such as through impact investments that are targeted

toward specic program-related social objectives. Many of the

largest companies in the world have philanthropy built into their

business plans, and the trend is increasingly turning toward seeing

nancial performance as just one of the many measures of a

business’s success.

Impact investing

Impact investments are as those that set out to achieve positive

social and environmental impacts, in addition to nancial return,

while measuring the achievement of both. Impact investing

dismisses the notion that protable investments and giving money

to charitable work are separate activities, distinguishing it from

other forms of philanthropy. Impact Investing Australia suggests

that the market for such investments is expected to reach US$500

billion to US$1 trillion globally over the next decade.

Collective impact

No single policy, program or organization can tackle the

increasingly complex problems the world faces today. Collective

impact refers to the commitment of a group of important actors

from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specic

social problem. The collective impact approach was rst discussed

by John Kania and Mark Kramer in the 2011 StanfordSocial

InnovationReview. They identied ve key elements of an effective

collective impact approach, including a common agenda, the

consistent measurement of results, mutually reinforcing activities

and the use of a backbone organization.

Responsible investment framework

A responsible investment framework helps organizations use

their wealth to make socially ethical investment decisions, often

based on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors.

Such frameworks will commonly involve thorough monitoring

practices, rigid reporting policies and a great deal of accountability

and transparency. For many organizations that are using part of

their portfolio for ethical or impact investments, a responsible

investment framework can ensure that the remainder of their

portfolio is aligned to the same goals and does not deter or diminish

the impact outcomes sought by part of their portfolio. An example

of this is the Rockefeller family’s decision to sell their investments in

fossil fuels to reinvest in renewable energy.

20 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Section

3

Family ofces are unique to the family that sets them up. And,

to dene what an “average family ofce” should look like is not

meaningful. Their size may vary from 1 employee to up to 50 or

more, depending on the services provided, the number of family

members to be served, and how the services are to be delivered.

Despite there being no standard denition of a family ofce,

anecdotal evidence suggests that a full-service family ofce will

cost a minimum of US$1m annually to run, and in many cases it

will be much more. This would suggest that for a family ofce to be

viable, a family should be worth between US$100m and US$500m.

Of course, a family ofce can be set up with US$100m or even less,

but the service range will probably be limited to administration,

control of assets, consolidation and risk management. A fully

integrated family ofce will require a great deal more wealth.

Table 3.1 breaks this down in more detail.

Figure 3.1. Family ofce types based on assets and costs

Family ofce type Assets (US$m) Overhead cost per year (US$m)

Administrative

50 to 100 0.1 to 0.5

Hybrid

100 to 1,000 0.5 to 2.0

Fully integrated

> 1,000 1.0 to 10.0

Source: TheGlobalStateofFamilyOfces,Cap Gemini, 2012.

Staff costs

Research from consultancy Family Ofce Exchange has found that a

signicant portion of the total costs of a family ofce are allocated

to staff compensation and benets.

1

Figure 3.2 illustrates this cost breakdown in more detail.

A fully integrated family ofce — providing most, if not all, of the

services mentioned in section three — would have a typical staff

structure represented in Figure 3.3.

Setup costs would also include the employment of headhunters for

recruitment, compensation specialists, relocation costs, legal setup

costs, and the search for infrastracture such as ofce space and

technology solutions.

1. Family Ofce Primer,

FamilyOfceExchange,

2013.

The costs of running a

family ofce

21EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Figure 3.2. US family ofce costs

Oversight ofce with staff of 12 and internal

Chief Investment Ofcer

Figure 3.3. Family ofce staff

2. TheGlobalFamilyOfce

Report, Campden

Research/UBS, 2015.

Overall costs

Family ofces typically have operating costs of between 30 basis

points and 120 basis points. A recent report by Campden Research

and UBS

2

states that family ofce costs are on the rise globally,

approaching the 1% mark as ofces employ more staff. The report

concludes that the costs of running family ofces has increased

as a percentage of Assets Under Management (AUM) over recent

years and that the costs remain on an upward trend. Ofces with

the lowest running costs focus primarily on a limited number of

wealth management services, such as handling real estate holdings.

However, there is no strong correlation between the size of AUM

and the operating costs.

Oversight ofce with staff of three

External investment fees

External professional fees and owner education

Office operations

Staff compensation with chief investment officer

39%

9%

27%

25%

External investment consulting fees

External investment management and

custody fees

External professional fees and owner education

Office operations

Staff compensation

16%

32%

10%

14%

28%

Source: Thecostofcomplexity,understandingfamilyofcecosts, Family Ofce Exchange, 2011.

Source: Aguidetotheprofessionalfamilyofce, Family Ofce Exchange, 2013.

Chief

Financial Officer

Chief

Investment Officer

Chief

Operating Officer

Accountants

Controllers

Lawyer

Investment

analysts

Administrative

staff

Information

technology

Chief Executive Officer

22 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Section

4Family ofce governance

Dening governance structures

Family ofce governance is often ignored as a topic because

families usually focus on managing their nancial assets and

investments and overlook the importance of implementing good

governance practices in their private family ofce. Below is a guide

to major issues regarding family ofce governance.

Strategic planning

It is important to start the initial discussion with the family

participating in a long-term review of their vision and strategy for

the future. Such an exercise is very helpful in capturing the wishes

and vision of the family as well as informing the management so

they can develop a long-term strategic plan.

Board of directors

As family ofces usually stem from the desire of the founders

to preserve the family wealth and protect the future of the next

generation, they often tend to depend on trusted advisors whom

they know well and have been working with for several years.

Accordingly, the concept of a board of directors managing the

strategic direction of the family ofce is often neglected. However,

when the wealth is transferred to the next generation, managing

the family ofce in the same manner may be a cause of conict and

dispute between family members.

There is a need to dene a proper governance structure that takes

into account the requirements of all family members. Electing a

strong and active board that follows the direction of the family and

takes into consideration the interests of all family members, not just

a few, is very important. Moreover, including independent directors

who add their experience and provide independent advice to the

family is crucial in enhancing, strengthening and diversifying the

family ofce investments and operations.

In many cases families are very reluctant to include independent

directors and open their books to outsiders because of privacy

issues. Those families may choose to appoint an interim advisory

board with no voting powers to help strengthen the board and

provide advice on specic topics. This step helps the family prepare

and be more comfortable with including independent board

members in the future, to create a fully functional board.

23EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Accountability

Founders are often reluctant to share much nancial information

with their children, in an effort to shelter and protect them

from being accountable for their nancial decisions. This is not

a sustainable model; with responsibility comes accountability,

and the family members need to be prepared from an early age

to be responsible for their actions and understand that they will

be accountable to the rest of the family. In order for them to be

successful in the stewardship of wealth, they need to create the

process and the opportunity for family members to grow and

develop their skills and talent, as well as manage their nancial

affairs responsibly.

Developing a proper structure

It is important for every family ofce to develop a proper

management and legal structure to protect the operation of

the family ofce and the assets of the family. Developing proper

policies and procedures, and identifying key talents capable of

leading the ofce are important factors in the successful operation

of the family ofce. Moreover, in order to protect the family from

any unnecessary tax implications and legal impact, it is also very

important to select the right legal structure and jurisdiction for

setting up the ofce.

Block-holder and double agency costs

A crucial point for family ofces to take into account when

considering governance is that they are often exposed to

substantial agency costs that result from managing nearly every

aspect of the ofce.

As a result of the two main functions family ofces serve, i.e.,

managing complex asset bases and aligning family interests,

family ofces encounter family block-holder as well as double

agency problems that can result in additional costs (Zellweger

and Kammerlander, 2015). Family block-holder costs can emerge

when not all family members agree on the strategy of the

family ofce. For example, one member of the family might be

interested in short-term liquidity to nance lifestyle ambitions,

whereas other members might be more interested in holding onto

investments for potentially better long-term gains. This can lead to

a misalignment of interest, which is a “cost” to the efcient running

of the family ofce.

24 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Double agency costs, similarly to family block-holder costs, can

emerge when the interests of the family conict with the interests

of those non-family members hired to manage the family’s wealth.

An example of this is when the family is more concerned with the

long-term outcomes of managing their wealth, compared with the

often short-term outlook of family ofcers and their subordinated

asset managers who look to maximize their own nancial benets

to the detriment of the family’s wealth. This leads to a misalignment

of interests, which is a “cost” to the efciency of the family ofce.

Family block-holder costs

Families do not necessarily act in a unied way. Rather, family

dynamics might counteract interest alignment and lead to conicts

involving costs that are referred to as family block-holder costs. A

lack of governance of the family owners opens up the possibility of

negative family dynamics.

Particularly destructive effects are expected in an EFO, which

is characterized by the absence of formal and unambiguous

governance instruments, such as boards, regulations and statutes.

There are no clear responsibilities in controlling the EFO that

shares part of its resources, staff and command structure with

the operating business, which in turn could increase the possibility

of family block-holder conicts and the related costs compared

with an SFO.

An increase in conicts and struggles between family members

can lead to particularly severe effects on family wealth, since

conicted family block-holders might be tempted to engage

in spendthrift lifestyles. This could split the family wealth and

consequently prevent the cohesion of the family and its assets

across generations. Also, the absence of clear responsibilities,

accountabilities and rules of engagement on the part of EFO

employees who serve two masters could even aggravate the effects

of family block-holder conicts and their consequent costs.

Double agency costs

Costs resulting anytime authority is vertically delegated down

two tiers of hierarchies, are referred to as double agency costs.

Double agency creates problems of control and accountability

when two sequential sets of control relationships are involved,

such as from the family as wealth owner to the family ofcer

and the subordinated asset managers.

The principal’s (i.e., the family’s) loss of control over its agents

(the family ofcers and the advisors) follows from incentives for

opportunistic behavior. The striving for more autonomy and the

behavior by agents to receive a remuneration is a major problem.

The principal is increasingly exposed to biased information passed

on from asset managers to the family ofcer and subsequently

from the family ofcer to the family.

This phenomenon gains particular intensity in the family ofce

environment, where the principal family usually lacks the

sophisticated nancial and investment knowledge that family ofce

staff have, thereby increasing the probability of agents’ empire-

building at the expense of the principal. Because the family ofce

often serves as the trusted advisor of the family for much of the

family’s nancial affairs, and given the limited insights and know-

how of the family into the complexity of these affairs, the family

ofce is potentially well placed to act opportunistically if it is not

properly monitored or incentivized.

Incentives for opportunism arise particularly in family ofces

since the family as principal may have difculties in controlling the

activities of a family ofcer and even more difculties in supervising

asset managers who are often external experts that are not part

of the family ofce’s own staff. Monitoring the family ofcer and

his or her dealings with the asset managers is particularly difcult

in SFOs. The formal setup and hierarchies often serve as barriers

preventing the family from closely monitoring family ofce staff,

accessing rst-hand information on an ongoing basis, supervising

asset allocation decisions, and controlling the efciency of the

family ofce operations.

If the family fails to provide adequate oversight, family ofce

staff will be more prone to engage in collusive agreements with

external asset managers and service providers or “self-dealings,”

where family ofcer and asset managers internally agree upon

opportunistic dealings to the detriment of the family’s wealth. Such

conduct by family ofcers and asset managers undermines the

preservation of wealth and generates potential reductions of the

wealth and inefciencies for the family.

Family versus non-family members

The extent of double agency costs certainly depends on whether

family ofce staff are composed of family or non-family members.

It reects the dilemma that families usually have to deal with-

25EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

employing as family ofcer a non-family member who is well-versed

in nancial matters, or relying on a family member as family ofcer

who might not have that competence but is trustworthy, thus

diminishing double agency costs.

Successfully navigating concerns between principals and agents is

not an easy task for families. But, they can mitigate these tensions

by implementing appropriate governance structures and incentive

contracts. Selecting appropriate benchmarks is also important,

as poorly designed benchmarks may cause fund managers and

external partners to work against what families wish to achieve.

Families should also consider establishing formal processes to make

investment decisions, as this can help family ofces to set clearly

dened boundaries and goals, and avoid ad hoc decisions that are

not in line with the broader mandate or long-term strategy.

The family ofce dilemma

Ultimately, family ofces face a dilemma: on the one hand, the

family as the ultimate asset owner wishes to appoint the most

qualied people to run the family ofce. Sometimes, a competent

person is available within the family, but this is not often the case.

Then, a professional non-family family ofcer has to be appointed.

The benet of doing so is that family block-holder conicts can be

mitigated through the non-family member running the family ofce.

But a natural consequence of such delegation of control is the

risk of losing control altogether. This is particularly true for wealth

structures that involve trusts and foundations, but the problem is

also apparent in the case of SFOs.

In light of this dilemma between professionalization and loss

of control, families with a family ofce will have to nd ways

to combine the best of both worlds, achieving professional

management while maintaining control.

Boards, investment advisory committees, the personal involvement

of family members in selected activities, incentive systems for the

managers and monitoring systems are often put in place to tackle

the challenge.

26 EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Section

5

Constructing a business plan,

stafng and strategic planning

Planning a strategic way forward

If a family decides that it needs a family ofce, what are the

next steps?

It is an increasingly widely held view that a family ofce — even

an SFO — should not operate in the longterm on a decit basis,

i.e., purely as a cost center. Most successful entrepreneurs would

not start a business without a written business plan. Once the

business is running, these entrepreneurs generally create and

update short- and long-term strategic plans for the business.

Leading family ofces provide that same level of diligence for

themselves. A crucial part of the strategic plan is stafng, which is

discussed in the section 5.1, Familyofcestaff.

Business plan

The rst step in creating a business plan is understanding the

vision for the family (usually described in a family charter), and

subsequently the vision for the family ofce. Here are some of the

key components of such a plan:

Summary

It is important to describe the vision for the family ofce, explain

why it is being created, whom it is designed to serve and how it is

expected to evolve. Is there an intention to serve other families,

thus becoming an MFO, or just to serve the single family?

Family business

Is there a business linked to the family ofce, or has the business

been sold? Family ofces often start as an EFO within the business,

and become a separate entity when the family, its complexity and

its risks outgrow the business staff.

27EY Family Ofce Guide Pathway to successful family and wealth management

Structure

What type of entity will house the ofce, and who will own it? What

is the plan for passing ownership across generations (assuming the

ofce is intended to support more than the rst generation)? Will

the ofce support businesses, with the potential of having some

expenses deductible against business income? It is important to

discuss the intended tax impact of the structures to ensure that

the family understand their potential consequences. Tax and legal

advisors generally have a signicant advisory role on structure and

jurisdiction.

Jurisdiction

Global families need to consider which country the ofce will be

based in, but this decision goes much further. Within specic

countries such as the US, states have vastly different tax, legal, and

judicial benets. The business plan should specify where the ofce

and entities will be based.

Governance

Governing boards or councils need to be dened, including how

they will work. This structure often includes a family council,

investment committee and even a philanthropic committee. The

plan should dene what boards will exist, how board members will

be selected, how the boards will change over time, how decisions

will be made within them, and whether they will include non-family

participants.

Services

There needs to be a description of the services the ofce will

deliver, and for which family members or generations. In some

cases, there is a list of base services available to all family members,

with additional services available on an à la carte basis.

Stafng

This section will need to discuss the types and number of staff in

the ofce, in addition to the organization or reporting structure.

Often, the family ofcer reports to a family council or perhaps to

a particular family member. It also helps if this section discusses

conditions under which family members may be permitted to work

in the ofce.

Operations

How will the services be delivered, and what technology is required