AFFORDABLE

BROADBAND

FCC Could Improve

Performance Goals

and Measures,

Consumer Outreach,

and Fraud Risk

Management

Report to Congressional Requesters

January 2023

GAO-23-105399

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-23-105399, a report to

congressional requesters

January 2023

AFFORDABLE BROADBAND

FCC Could Improve Performance Goals and

Measures, Consumer Outreach, and Fraud Risk

Management

What GAO Found

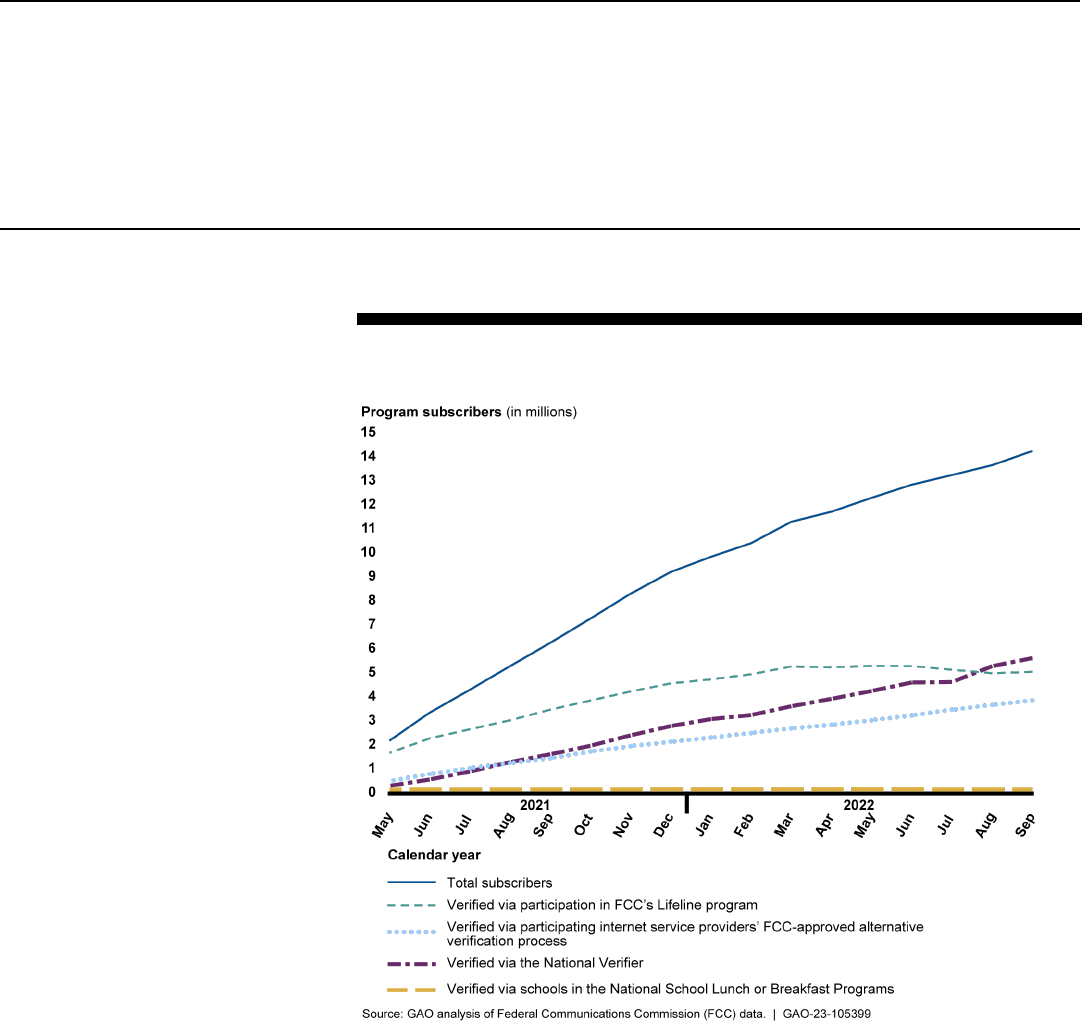

The Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Affordable Connectivity

Program offers eligible low-income households discounts on the cost of their

broadband service and certain devices. FCC reimburses participating internet

service providers for providing these discounts. Since launching, the program

has grown to include over 14-million subscribers.

FCC Affordable Connectivity Program’s Subscribers, May 2021–September 2022

FCC established some performance goals and measures for the program.

However, the goals and measures do not fully align with key attributes of

effective performance management. For example, FCC’s goals and measures

lack specificity and clearly defined targets, raising questions about how effective

these goals and measures will be at helping FCC gauge the program’s

achievements and identify improvements.

FCC has also engaged in various outreach efforts to raise ACP’s awareness and

translated its outreach materials into non-English languages to reach eligible

households with limited-English proficiency. However, GAO reviewed a selection

of these materials and the process to translate them and found that they did not

fully align with leading practices for consumer content or for developing

translated language products. For example, the translations’ quality varied due to

lack of clarity and incompleteness. Also, FCC’s translation process lacked

elements that could have improved the materials, such as testing with the target

audience. FCC has also not developed a plan to guide its overall outreach

efforts. Quality translations are key to informing eligible households with limited-

English proficiency, which may include communities FCC has indicated are

important to reach. A comprehensive plan to guide its outreach efforts would help

ensure funds dedicated to outreach are used most effectively.

FCC has taken steps to manage fraud risks in the program, but FCC’s efforts do

not fully align with selected leading practices in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework.

For example, FCC has conducted a fraud risk assessment but has not developed

an antifraud strategy to address the identified risks. It also has not developed a

process to conduct such risk assessments regularly. Further, FCC has not

developed processes to monitor certain antifraud controls. GAO identified

weaknesses in these controls, including potential duplicate subscribers,

subscribers allegedly receiving fixed broadband at PO Boxes and commercial

mailboxes, and subscribers with broadband providers’ retail locations as their

primary or mailing addresses. Without regular fraud risk assessments, an

antifraud strategy, and sufficient monitoring of controls, FCC may not be able to

effectively prevent and detect fraud in this over $14 billion program.

View GAO-23-105399. For more information,

contact

Andrew Von Ah at (202) 512-2834 or

.

Why GAO Did This Study

Broadband, or

high-speed internet, is

critical

since everyday activities

increasingly occur online, as

highlighted by the COVID

-19

pandemic. Yet the inability to afford

broadband presents barriers to access

for some and contributes to the gap

between those with and with

out

access, known as the “digital divide.”

As required by statute, FCC launched

the Affordable Connectivity Program

in

December 2021 to help low

-income

households afford broadband, building

from

FCC’s May 2021 launch of the

predecessor

Emergency Broadband

Benefit program

.

GAO was asked to review FCC’s

implementation

of the program. This

report

assesses FCC’s program

efforts

in:

(1) establishing performance goals

and measures, (2) conduct

ing

outreach, and (3) managing

fraud

risks.

GAO reviewed program

documentation

, including outreach

materials translated into five

non-

English

languages; analyzed

enrollment data from May 2021 to

September

2022; interviewed FCC

official

s; and compared FCC’s efforts

in each area to applicable leading

practices identified

in prior GAO work

or other federal sources.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making

nine

recommendations,

including that FCC improve its program

goals and measures, revise its

language translation process, develop

a consumer outreach plan, and

develop and imp

lement various

processes for managing fraud risks.

FCC agreed with our

recommendations and described its

plans to address each one.

Page i GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Letter 1

Background 5

FCC Has Established Some Performance Goals and Measures for

Its New Broadband Affordability Program, but They Do Not

Fully Align with Leading Practices 11

FCC Has Engaged in Outreach for Its New Broadband

Affordability Program, but Its Language Translation Process

and Outreach Planning Do Not Fully Align with Leading

Practices 18

FCC Has Taken Steps to Manage Fraud Risks in Its New

Broadband Affordability Program, but Its Efforts Do Not Fully

Align with Selected Leading Practices 33

Conclusions 47

Recommendations for Executive Action 48

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 49

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 52

Appendix II Analysis of ACP and EBB Enrollment Data 63

Appendix III Printable Versions of Interactive Figure 3 68

Appendix IV Comment from the Federal Communications Commission 72

Appendix V GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 81

Tables

Table 1: FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program’s (ACP)

Performance Goals and Measures 11

Table 2: Key Attributes of Effective Performance Goals and

Measures 12

Contents

Page ii GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Table 3: Examples of FCC Partnerships with Federal Agencies to

Raise Awareness for the Affordable Connectivity Program

(ACP) 19

Table 4: Comparison of FCC’s Original Translation Process to

Recommended Practices for Developing Public-Facing

Translated Language Products 29

Table 5: Leading Practices for Planning Effective Consumer

Outreach 32

Table 6: List of Participating Providers Selected for Website

Review 55

Table 7: Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) Non-

English Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) Outreach

Materials Reviewed 57

Table 8: List of Stakeholders Interviewed 59

Table 9: Selected Leading Practices for Fraud Risk Management 61

Figures

Figure 1: Overview of the Fraud Risk Management Framework 10

Figure 2: FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program’s (ACP)

Performance Goals and Measures Compared with Key

Attributes of Effective Performance Goals and Measures 14

Figure 3: Selection of FCC’s Chinese, French, Korean, Spanish,

and Vietnamese Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP)

Outreach Materials Compared with Leading Practices for

Consumer-Oriented Content 23

Figure 4: Examples of Duplicated Spanish Text on FCC’s Spanish

Version of the Affordable Connectivity Program

Consumer FAQ Webpage and English Text on Spanish

Social Media Image 25

Figure 5: FCC’s Original Translation Process for Creating Non-

English Affordable Connectivity Program Consumer

Outreach Materials 28

Figure 6: Key Elements of an Antifraud Strategy 40

Figure 7: Example of Anonymized Potential Duplicate Subscribers

and Their Related Claims in FCC’s Affordable

Connectivity Program 43

Figure 8: Examples of Issues Related to PO Box and Commercial

Mailbox Addresses in Affordable Connectivity Program

Enrollment Data 46

Page iii GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Figure 9: Enrollment in FCC’s Emergency Broadband Benefit

Program (EBB), Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP),

and Lifeline, May 2021–September 2022 64

Figure 10: Enrollment in FCC’s Emergency Broadband Benefit

Program (EBB) and Affordable Connectivity Program

(ACP) by Lifeline Enrollment Status, May 2021–

September 2022 65

Figure 11: Enrollment in FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program

(ACP) by State as of September 2022 66

Figure 12: Enrollment in FCC’s Emergency Broadband Benefit

Program (EBB) and Affordable Connectivity Program

(ACP) by Method Used to Verify Program Eligibility, May

2021–September 2022 67

Figure 13: Printable Version of Interactive Figure 3 – Clarity and

Accuracy 68

Figure 14: Printable Version of Interactive Figure 3 –

Completeness 69

Figure 15: Printable Version of Interactive Figure 3 – Practicality 70

Figure 16: Printable Version of Interactive Figure 3 – Managing

Users’ Expectations 71

Page iv GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Abbreviations

ACP Affordable Connectivity Program

EBB Emergency Broadband Benefit program

FAQ frequently asked questions

FCC Federal Communications Commission

IIJA Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

PII personally identifiable information

USAC Universal Service Administrative Company

Verifier National Lifeline Eligibility Verifier

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

January 18, 2023

The Honorable Roger F. Wicker

United States Senate

The Honorable John Thune

United States Senate

Broadband, or high-speed internet, has become critical for daily life as

everyday activities like work, school, health care appointments, and

access to economic opportunity and civic engagement increasingly occur

online. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of

access to broadband and highlighted the gap between those with and

without access, known as the “digital divide.” Yet, the inability to afford

broadband service presents barriers to access, particularly for low-income

households. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has

reported that these households have lower rates of home broadband

subscriptions.

1

Further, a nationally representative survey by Consumer

Reports reported that nearly a third of respondents who lack a broadband

subscription said it was because it costs too much, while about a quarter

who do have broadband said they find it difficult to afford.

2

Regarding

rates of home broadband subscription, the U.S. Census Bureau has also

reported that households with limited-English proficiency lag behind other

households.

3

As required by statute, FCC created the Affordable Connectivity Program

(ACP), the successor to the Emergency Broadband Benefit program

(EBB). FCC established EBB to offer eligible low-income households

discounts on the cost of broadband service and certain devices, and to

reimburse internet service providers that participate in the program

1

In the Matter of Inquiry Concerning Deployment of Advanced Telecommunications

Capability to all Americans in a Reasonable and Timely Fashion, Fourteenth Broadband

Deployment Report, FCC 21-18, para. 47 (2021).

2

Consumer Reports, Broadband Survey: A Nationally Representative Multi-Mode Survey

(July 2021).

3

U.S. Census Bureau, Computer and Internet Use in the United States: 2018

(Washington, D.C.: April 2021).

Letter

Page 2 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

(participating providers) for these discounts.

4

In November 2021, the

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) made several changes to

the program to transform it from a temporary, emergency program to a

longer-term program known as ACP, and provided an additional $14.2

billion in funding.

5

The IIJA also included new provisions on conducting

outreach to eligible households to raise awareness of ACP. As required

by the IIJA, FCC launched ACP on December 31, 2021, building from its

launch of EBB in May 2021. FCC established ACP’s final rules in January

2022, after considering public comments submitted by stakeholders.

6

Although ACP is new, like its predecessor, EBB, it builds from and relies

in part on the operation of FCC’s Lifeline program, which has provided

eligible low-income households discounts on broadband service since

2016. For example, the not-for-profit Universal Service Administrative

Company (USAC) administers both ACP and Lifeline on behalf of FCC,

and both programs use the same systems for household eligibility

verification, enrollment in the program, and participating provider

reimbursement claims. We and others have previously reported on the

susceptibility of Lifeline to fraud, and FCC has imposed millions of dollars

in penalties on providers for apparent program violations.

7

Some

stakeholders have raised concerns about program integrity for ACP,

given the program’s connections to Lifeline, while others have highlighted

the positive role that ACP can play in closing the digital divide.

4

The December 2020 Consolidated Appropriations Act directed FCC to establish this

program. Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, div. N, tit. IX, §

904, 134 Stat.1182, 2129-36.

5

The $14.2 billion was in addition to the $3.2 billion previously provided for EBB. The

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Pub. L. No. 117-58, § 60502(a)(1)(A), (a)(2),

135 Stat. 429, 1238-39 (2020) (authorizing the Affordable Connectivity Program); div. J,

tit. IV, 135 Stat at 1382 (providing additional funding). This program is now codified in 47

U.S.C. § 1752.

6

In the Matter of Affordable Connectivity Program, Emergency Broadband Benefit

Program, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, FCC 22-2

(2022).

7

See, for example, GAO, Telecommunications: Additional Action Needed to Address

Significant Risks in FCC’s Lifeline Program, GAO-17-538 (Washington, D.C.: May 30,

2017); and Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs, TracFone Wireless to Pay

$13.4 Million to Settle False Claims Relating to FCC’s Lifeline Program, Press Release

Number 22-323 (Apr. 4, 2022). The identification of improper payments could suggest that

a program is vulnerable to fraud; however, not all improper payments are fraudulent.

Page 3 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

You asked us to review FCC’s implementation of ACP.

8

This report

examines the extent to which FCC’s ACP efforts align with relevant,

selected leading practices in: (1) establishing performance goals and

measures; (2) conducting outreach; and (3) managing fraud risks.

To assess FCC’s efforts to establish ACP performance goals and

measures, we reviewed documentation and data. For example, we

reviewed the IIJA and records in FCC’s ACP proceeding. For additional

context on ACP’s performance, we analyzed enrollment data from May

2021 to September 2022, which covers the beginning of EBB to the end

of the third quarter following the launch of ACP. We assessed the

reliability of these data and determined that they were sufficiently reliable

for the purposes of our reporting objective. We assessed FCC’s efforts

against leading practices for performance goals and measures, including

the key attributes for such goals and measures identified in our prior

work.

9

To assess FCC’s ACP outreach efforts, we also reviewed agency

documentation. For example, we reviewed FCC’s ACP outreach materials

(including webpages and items from the outreach toolkit) and FCC’s

outreach plan for EBB (the predecessor program). To assess FCC’s

outreach materials for households with limited-English proficiency, we

reviewed a selection of FCC’s non-English ACP outreach materials in

Chinese, French, Korean, Spanish, and Vietnamese, as well as FCC’s

language translation process for developing these materials. We

assessed how well the non-English materials aligned with applicable

leading practices for consumer-oriented content drawn from various

8

Senator Wicker’s request was in his role as Ranking Member of the Senate Committee

on Commerce, Science, and Transportation in the 117

th

Congress, and Senator Thune’s

request was in his role as the Ranking Member of that committee’s Subcommittee on

Communications, Media, and Broadband.

9

GAO, Agencies’ Annual Performance Plans Under the Results Act: An Assessment

Guide to Facilitate Congressional Decisionmaking, GAO/GGD/AIMD-10.1.18

(Washington, D.C.: February 1998); The Results Act: An Evaluator’s Guide to Assessing

Agency Annual Performance Plans, GAO/GGD-10.1.20 (Washington, D.C.: April 1998);

and Tax Administration: IRS Needs to Further Refine Its Tax Filing Season Performance

Measures, GAO-03-143 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 22, 2002). These reports establish

guides for assessing and evaluating agency performance plans and attributes of effective

performance goals and measures, and we have reiterated these practices in our reporting

on agencies’ efforts to manage for results. See https://www.gao.gov/leading-practices-

managing-results-government.

Page 4 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

federal sources that we have used in prior work.

10

We also assessed

FCC’s translation process against applicable recommended practices

from the U.S. Census Bureau for developing public-facing translated

products.

11

We assessed FCC’s EBB outreach plan against the leading

practices for consumer education planning identified in our prior work.

12

To assess FCC’s efforts to manage ACP fraud risks, we reviewed

documentation and data. For example, we reviewed FCC’s fraud risk

assessment for ACP and relevant program policies and guidance.

Additionally, we analyzed a snapshot of ACP enrollment data as of April

1, 2022, and matched relevant elements of these data against U.S. Postal

Service and Social Security Administration data. We assessed the

reliability of these data and determined that they were sufficiently reliable

for the purposes of our reporting objective. We assessed FCC’s fraud risk

management activities against selected leading practices in our Fraud

Risk Framework.

13

Finally, for additional agency information and context on all of our

objectives, we interviewed FCC and USAC officials and a selection of 27

stakeholders. We interviewed stakeholder representatives from 8 industry

associations; 5 state, local, and tribal entities; and 14 advocacy groups

selected to obtain a variety of viewpoints from a cross-section of interests.

While their views are not generalizable to all stakeholders, they provided

us with a variety of perspectives.

14

Similarly, we reviewed comments

10

U.S. Digital Service, Digital Services Playbook, accessed Dec. 10, 2021,

https://playbook.cio.gov/; U.S. Web Design System, Design Principles, accessed Dec. 10,

2021, https://designsystem.digital.gov/design-principles/; and General Services

Administration, Top 10 Best Practices for Multilingual Websites, accessed Dec. 10, 2021,

https://digital.gov/resources/top-10-best-practices-for-multilingual-websites/.

11

U.S. Census Bureau, Developing Public-Facing Language Products: Guidance From the

2020 Census Language Program (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 3, 2021). According to this

guidance, the bureau developed this product to share detailed information on how the

agency successfully developed and executed the 2020 Census language program, which

translated over 7 million words for more than 2,500 projects.

12

GAO, Digital Television Transition: Increased Federal Planning and Risk Management

Could Further Facilitate the DTV Transition, GAO-08-43 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 19,

2007).

13

GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO-15-593SP

(Washington, D.C.: July 2015).

14

Throughout this report, we refer to “some” stakeholders if representatives from 2–5

entities expressed the view (and “several” if 6–10, and “many” if 11 or more).

Page 5 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

submitted by stakeholders in FCC’s ACP proceeding. Appendix I

describes our objectives, scope, and methodology in greater detail.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2021 to January 2023

in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain

sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our

findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that

the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and

conclusions based on our audit objectives.

ACP provides eligible low-income households with monthly discounts on

the cost of their broadband service and a one-time discount on the cost of

certain devices. Eligible households can receive a discount of up to $30

per month ($75 for those on tribal lands) on their broadband service, and

a one-time discount of up to $100 on a tablet, laptop, or desktop

computer if the household contributes more than $10 but less than $50

toward the device’s purchase price.

15

To be eligible, a household must

meet the eligibility criteria for a participating provider’s own low-income

broadband assistance program or one of the following conditions:

• have total income at or below 200 percent of the Federal Poverty

Guidelines;

16

• participate in Lifeline or certain other government assistance

programs;

17

15

This means the total cost of the device to the household, including discount, can be no

more than $150. Some providers offer tablets, for example, at this price point or may offer

additional discounts to meet this price point.

16

The Department of Health and Human Services issues these guidelines each year

based on a household’s size and location. For example, 200 percent of the 2022

guidelines could range from a single-person household that resides in one of the 48

contiguous states or the District of Columbia that earns $27,180, to an 8-person

household in Alaska that earns $116,580.

17

These programs include Federal Public Housing Assistance; Medicaid; the National

School Lunch or Breakfast Programs, including through the Department of Agriculture’s

Community Eligibility Provision; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women,

Infants, and Children; the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; Supplemental

Security Income; and Veterans Pension or Survivor Benefits.

Background

The Affordable

Connectivity Program

Page 6 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

• participate in certain government assistance programs and live on

qualifying tribal land;

18

or

• have received a federal Pell grant during the current award year.

A household can apply to the program by mail, online, or through a

participating provider. To process applications, FCC uses a modified

version of the same online tool it uses for Lifeline. Known as the National

Lifeline Eligibility Verifier (Verifier), FCC completed its launch of this tool

in 2020 in response to concerns about Lifeline fraud.

19

Historically,

providers verified that applicants met Lifeline eligibility requirements

before providing them with discounted service. In response to concerns

that FCC’s reliance on providers to make such eligibility determinations

left the program vulnerable to fraud, FCC established the Verifier to shift

responsibility for eligibility verification from providers to USAC.

The Verifier relies on automated connections to federal and state benefits

databases and other automated sources to validate an applicant’s

identity, address, and participation in qualifying programs.

20

When

applicants cannot be automatically verified, they must submit

documentation to USAC for manual review. An applicant may also apply

in person with the assistance of a participating provider, or through a

provider’s website if the provider has established an interface between its

website and the Verifier. Alternatively, a provider may use its own FCC-

approved alternative verification process to determine eligibility (in

18

These programs include Bureau of Indian Affairs General Assistance; the Food

Distribution Program on Indian Reservations; Tribal Head Start (only if the household

qualified through the program’s income standard); and Tribal Temporary Assistance for

Needy Families. FCC’s definition of tribal lands for ACP purposes includes “any federally

recognized Indian tribe’s reservation, pueblo, or colony, including former reservations in

Oklahoma; Alaska Native regions established pursuant to the Alaska Native Claims

Settlement Act (85 Stat. 688); Indian allotments; Hawaiian Home Lands - areas held in

trust for Native Hawaiians by the state of Hawaii, pursuant to the Hawaiian Homes

Commission Act, 1920 July 9, 1921, 42 Stat. 108, et. seq., as amended; and any land

designated as such by the Commission for purposes of this subpart pursuant to the

designation process in § 54.412.” 47 C.F.R. § 54.400(e).

19

We previously reported on the Verifier’s implementation. See, GAO,

Telecommunications: FCC Has Implemented the Lifeline National Verifier but Should

Improve Consumer Awareness and Experience, GAO-21-235 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 28,

2021).

20

According to USAC reporting as of January 2022, the Verifier has database connections

with 2 federal agencies (the Department of Housing and Urban Development and Centers

for Medicare and Medicaid Services) and 23 states and territories (Colorado, Florida,

Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada,

New Mexico, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, South Carolina,

Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin).

Page 7 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

addition to, or instead of, the Verifier), or—if the applicant is qualifying

through a child or dependent who participates in the free and reduced

price school lunch or breakfast programs—may rely on schools for

verification. If a household already participates in Lifeline, it need not re-

verify its eligibility for ACP.

To subscribe to ACP once deemed eligible, applicants must contact a

participating provider to select a broadband service plan and have the

provider enroll them in the program and apply the discount. A program

subscriber may choose any broadband plan that the provider offers,

including mobile plans and bundled plans, though the discount cannot be

applied to video services. The provider enrolls the subscriber into the

program using the National Lifeline Accountability Database (the same

system used for Lifeline). When entering a subscriber into this database,

the provider must submit the subscriber’s

1. full name,

2. full residential address,

3. date of birth,

4. phone number associated with the ACP-supported service or email,

5. date the ACP discount was initiated, and

6. method by which the subscriber qualified for the program.

A subscriber can only receive the device discount from the same provider

from which it receives the service discount. Not all providers offer the

device discount. Providers receive reimbursements for these discounts

from FCC and manage their reimbursement claims using the Affordable

Connectivity Claims System (which is built on the Lifeline Claims

System).

While ACP shares similarities with Lifeline, ACP differs from Lifeline in

key ways. For example:

• Funding. ACP is funded by appropriations from the U.S. Treasury

General Fund, while Lifeline is funded by FCC’s Universal Service

Fund, which is in turn funded by required contributions from

telecommunications providers. FCC determines the amount of

contributions required from providers each quarter to support the

fund’s costs, and providers generally pass their contribution fees on to

their customers in the form of a line item on their phone bills.

Page 8 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

• Household eligibility. Household eligibility is more expansive under

ACP. Unlike ACP, Lifeline does not include the Special Supplemental

Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; the National

School Lunch or Breakfast Programs; Federal Pell Grants; or a

participating provider’s own low-income program as qualifying

programs. The income threshold for Lifeline eligibility is 135 percent of

the Federal Poverty Guidelines, as opposed to 200 percent for ACP.

21

• Participating providers. More providers can participate in ACP. To

participate in Lifeline, a provider must be designated as an eligible

telecommunications carrier by state public utility commissions or FCC;

this designation is not required to participate in ACP. Statutory and

regulatory requirements are associated with being designated an

eligible telecommunications carrier, such as requiring that the provider

offer an evolving level of services, such as broadband speeds,

throughout its service area.

• Discount and level of service. ACP provides subscribers with a

larger discount. Lifeline does not offer a device discount, and

subscribers may only receive a broadband service discount of up to

$9.25 per month ($34.25 for those on tribal lands) with Lifeline, as

opposed to up to $30 per month ($75 for those on tribal lands) with

ACP.

22

However, households may participate in both ACP and

Lifeline, if they choose, and may apply the discounts to the same or

separate qualifying services, and with the same or different providers.

Furthermore, providers must meet minimum standards for the Lifeline-

supported services they offer, such as minimum broadband speeds,

but there are no such minimum standards for ACP.

21

Income eligibility under ACP’s predecessor, EBB, was also 135 percent and EBB also

did not include the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and

Children. Under EBB, households were also eligible if the household experienced a

substantial loss of income due to job loss or furlough if the household’s total 2020 income

was at or below $99,000 for single tax filers and $198,000 for joint filers. A household

could also qualify through participation in a provider’s own COVID-19 program.

22

ACP’s predecessor, EBB, also offered a larger potential service discount of up to $50

per month.

Page 9 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Managers of federal programs are responsible for managing fraud risks

and implementing practices for combating those risks.

23

The objective of

fraud risk management is to ensure program integrity by continuously and

strategically mitigating both the likelihood and effects of fraud. Effectively

managing fraud risk helps to ensure that federal programs’ services fulfill

their intended purpose, that funds are spent effectively, and that assets

are safeguarded. In July 2015, we issued the Fraud Risk Framework,

which provides a comprehensive set of key components and leading

practices that serve as a guide for agency managers to use when

developing efforts to combat fraud in a strategic, risk-based way.

24

The Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 required the Office

of Management and Budget to establish guidelines for federal agencies to

create controls to identify and assess fraud risks and to design and

implement anti-fraud control activities, and to incorporate the leading

practices from the Fraud Risk Framework in the guidelines.

25

Although

that act was repealed in March 2020, the Payment Integrity Information

Act of 2019 requires these guidelines to remain in effect, subject to

modification by the Office of Management and Budget as necessary, and

in consultation with GAO.

26

As depicted in figure 1, the framework

describes leading practices within four components: (1) commit, (2)

assess, (3) design and implement, and (4) evaluate and adapt.

23

As we have previously reported, fraud and fraud risk are distinct concepts. Fraud—

obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation—is challenging to detect

because of its deceptive nature. Fraud risk (which is a function of likelihood and impact)

exists when people have an opportunity to engage in fraudulent activity, have an incentive

or are under pressure to commit fraud, or are able to rationalize committing fraud. Fraud

risk management is a process for ensuring program integrity by mitigating the likelihood

and impact of fraud. When fraud risks can be identified and mitigated, fraud may be less

likely to occur. Although the occurrence of fraud indicates there is a fraud risk, a fraud risk

can exist even if actual fraud has not yet occurred or been identified.

24

GAO-15-593SP.

25

Pub. L. No. 114-186, 130 Stat. 546 (2016); Payment Integrity Act of 2019 § 3(a)(4), Pub.

L. No. 16-117, 134 Stat. 113, 133 (2020) (repealing The Fraud Reduction and Data

Analytics Act of 2015).

26

Pub. L. No. 116-117, § 2(a), 134 Stat. 113, 131-32 (2020), codified at 31 U.S.C. § 3357.

Fraud Risk Management

Page 10 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Figure 1: Overview of the Fraud Risk Management Framework

Page 11 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

FCC has established some performance goals and measures for ACP, as

called for by leading practices.

27

According to leading practices, effective

organizations establish performance goals and measures to help assess

and manage program performance. First, organizations set goals that

clearly define intended program outcomes. Second, organizations

establish measures, which are concrete, observable conditions that

clearly link with the goals and allow organizations to assess, track, and

show the progress made toward achieving the goals. FCC established

three goals for ACP and two measures for each goal (see table 1).

Table 1: FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program’s (ACP) Performance Goals and Measures

Performance goal

Performance measures

Goal 1: Reduce the digital

divide for low-income

consumers

Measure 1: Estimate the prior internet access of ACP subscribers and monitor responses over time

and by area

Measure 2: Analyze ACP enrollments in areas with low adoption rates

According to FCC officials, to estimate prior access, FCC will survey subscribers. FCC’s target is to

analyze data quarterly to identify if there is an overall increase in first-time broadband connections, an

increase in first-time connections tied to targeted outreach, and higher than usual first-time

connections for a specific sub-group of subscribers. For the second measure, FCC will pair enrollment

data by geographic area with U.S. Census Bureau data and other data that FCC collects to calculate

an adoption rate and compare trends in areas with the lowest rates to those with the highest. FCC

aims to analyze, quarterly, areas with low rates to monitor progress relative to overall growth. FCC’s

target is to identify 5 to 10 Census tracts, ZIP codes, or counties in the bottom 20 percent of

broadband penetration rates that have low ACP participation to refer for targeted outreach, and 5 to 10

with high participation to examine reasons for success.

27

GAO/GGD/AIMD-10.1.18; GAO/GGD-10.1.20; and GAO-03-143.

FCC Has Established

Some Performance

Goals and Measures

for Its New

Broadband

Affordability Program,

but They Do Not Fully

Align with Leading

Practices

FCC Has Established

Some Program

Performance Goals and

Measures

Page 12 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Performance goal

Performance measures

Goal 2: Increase awareness

of and participation in ACP

Measure 1: Monitor participation over time and by area

Measure 2: Estimate ACP awareness

According to FCC officials, as part of the first measure, they will pair enrollment data with Census data

to calculate an ACP participation rate by state and extrapolate these findings to the ZIP code level. To

estimate awareness, they will survey the general public to calculate the percentage of respondents

who know about ACP and to capture information about those who do not. FCC’s target is to identify at

least three geographic areas or demographic groups that are the least aware of ACP to refer for

targeted outreach.

Goal 3: Ensure efficient and

effective administration of

ACP

Measure 1: Evaluate the speed and ease of the application and reimbursement processes

Measure 2: Evaluate the overall burden of the program on consumers

FCC stated that it will measure the burden on consumers using the same methodology it uses for its

Lifeline program to compute a monthly dollar figure.

Source: GAO analysis of In the Matter of Affordable Connectivity Program, Emergency Broadband Benefit Program, Report and Order and Further Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, FCC 22-2 (2022) and

other Federal Communications Commission (FCC) information. | GAO-23-105399

According to FCC officials, while FCC has not yet begun formally

reporting on any of these measures, ACP’s millions of subscribers to date

demonstrate its progress toward achieving these goals. We analyzed

program enrollment data and found that as of September 2022, about 14

million households had enrolled in ACP; this number is approximately a

third of the minimum estimate of eligible households.

28

See appendix II for

additional analysis on ACP participation.

In comparing FCC’s ACP performance goals and measures to leading

practices for effective goals and measures, we found that they did not

fully align with these practices. As noted above, according to leading

practices, effective organizations set program goals and measures; steps

FCC has taken. However, for goals and measures to be useful for

performance management, the practices indicate that they should reflect

key attributes, as summarized in table 2.

Table 2: Key Attributes of Effective Performance Goals and Measures

Key attributes

Definitions

Attributes of goals and

measures

Objective

Goals and measures are reasonably free of significant bias or manipulation

that would distort the assessment of performance and do not allow subjective

considerations to dominate.

Measurable and

quantifiable

Goals and measures include a quantifiable, numerical target or other value

and indicate specifically what should be observed, in which population or

conditions, and in what time frames.

28

We estimated eligibility using the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community

Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey. For more detail, see appendix I.

FCC’s Program Goals and

Measures Do Not Fully

Align with Leading

Practices

Pag

e 13 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Key attributes

Definitions

Primary function

Goals and measures reflect the program’s primary function and core

activities.

Linkage

Goals and measures reflect the agency’s strategic goals.

Additional attributes of goals

Results-oriented

Goals focus on the results the program expects to achieve. Outcome goals

are included whenever possible; output goals can supplement outcome

goals. Outputs are the services delivered by a program; outcomes are the

results of those services.

Crosscutting

Goals reflect the crosscutting nature of programs, when applicable. Goals of

programs contributing to the same or similar outcomes are complementary to

permit comparisons of results and identification of wasteful duplication,

overlap, or fragmentation.

Additional attributes of

measures

Clarity

Measure is clearly stated.

Reliability

Measure provides a reliable way to assess progress and produces the same

result under similar conditions.

Limited overlap

Measure gives new information beyond that provided by other measures.

Balance

The suite of measures covers an organization’s various priorities.

Government-wide

priorities

Each measure covers a priority such as quality, timeliness, efficiency,

outcomes, or cost of service.

Source: GAO/GGD/AIMD-10.1.18, GAO/GGD-10.1.20, and GAO-03-143. | GAO-23-105399

As shown in figure 2 and discussed below, FCC’s ACP performance

goals and measures lack some of these key attributes, in large part

because they lack specificity and clearly defined targets.

Page 14 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Figure 2: FCC’s Affordable Connectivity Program’s (ACP) Performance Goals and Measures Compared with Key Attributes of

Effective Performance Goals and Measures

FCC’s goals and measures largely align with some of the attributes of

effective goals and measures; specifically, those related to reflecting the

program’s primary functions and government-wide priorities, linking with

strategic goals, and being results-oriented and balanced. For example,

the goal to reduce the digital divide reflects the program’s primary

function, in that a primary function of the program is to address

broadband affordability for low-income households and in that affordability

is an aspect of closing the digital divide. Similarly, regarding the goal to

increase awareness and participation, the ACP final rules state that for

the program to achieve its full potential, households must be clearly

informed of the program’s existence, benefits, and eligibility qualifications,

Page 15 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

and how to apply.

29

Accordingly, awareness is primary to the program’s

success, as is participation in the program.

These two goals also link to FCC’s strategic goal to bring affordable

broadband to 100 percent of the population, including low-income

Americans, as part of addressing the digital divide, and the third goal

(ensure efficient and effective administration) links with FCC’s fostering

operational excellence strategic goal.

30

The digital-divide goal is also

results-oriented—since it expresses an outcome (a reduction in the digital

divide) of the program’s outputs (discounts on the cost of broadband

service)—as is the awareness-and-participation goal, since it covers an

outcome (participation) of increasing awareness. The measures for all

three goals also cover various government-wide priorities such as

outcomes, efficiency, and cost, and are balanced because they cover

various FCC priorities.

However, FCC’s current ACP goals and measures do not fully align with

many of the other attributes of effective goals and measures. For

example:

• Measurability and clarity. All three goals and their corresponding

measures are not expressed in a quantifiable manner, and all of the

measures also lack clarity. For example, none of the goals or

measures define a specific, numerical target. For instance, regarding

the measures on prior internet access and enrollment in areas with

low adoption, FCC has identified time frames and attempted to set

targets for each measure, but the targets are vague and not

numerical. Similarly, the measure on speed and ease of the

application and reimbursement processes does not define any

specific targets, populations, conditions, or time frames. The

measures’ lack of specificity also means they lack clarity. For

example, the specific program achievements that FCC is trying to

measure (e.g., a certain number of new broadband connections;

percentage increase in low-adoption areas; a certain level of

awareness, ease, or burden; or other value) are unclear. Additionally,

in the measure on participation over time and by area, it is not clear

what “over time” represents, and similarly, in the applications-and-

reimbursements measure, it is not clear what “ease” represents.

29

FCC 22-2, para. 190.

30

FCC, Strategic Plan: Fiscal Years 2022-2026 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 29, 2022).

Page 16 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

• Objectivity and reliability. The lack of specific targets and clarity

means it is also unclear whether the current goals and measures will

be objective or reliable measures of progress. For example, without

knowing what “specific subgroups” FCC is referring to in the measure

on prior internet access or what specific time periods or rate of

progress FCC is aiming for in the measures on participation and

awareness, FCC could present results in ways that make the results

look more or less favorable. Similarly, it is unknown how FCC will

weigh the subjective judgments of the different parties captured by the

applications-and-reimbursements measure, to ensure objectivity when

measuring performance. Regarding the measure on overall consumer

burden and its monthly-dollar-figure metric, it is unclear if FCC’s

methodology is reliable or aligns with the program’s primary functions

or intended results. FCC intends to divide the annual expenditures of

the program by the number of U.S. households to derive a monthly

dollar figure. If one of the goals of the program is to increase

participation and if the program’s expenditures increase as

participation increases, then the program’s expenditures-per-U.S.-

household will also increase. Therefore, it is unclear how this

approach meaningfully conveys program performance.

• Crosscutting and limited overlap. It is unclear how FCC intends to

consider the crosscutting nature of Lifeline across its current ACP

goals, and how some of the measures might overlap. Specifically,

FCC officials have indicated FCC’s interest in incorporating data from

Lifeline into its analyses. For example, in exploring first-time

broadband subscribership as part of the goal to reduce the digital

divide, this could mean those who were not already enrolled in Lifeline

and using it to obtain broadband prior to ACP enrollment. However,

the lack of specificity regarding what targets FCC is measuring means

it is unclear how FCC will gauge the performance of ACP and Lifeline

relative to each other. The lack of specificity on what achievements

are being measured means it is also unclear how much the measures

for the digital divide and participation goals will overlap, as they both

entail monitoring participation rates.

ACP provides eligible households with two possible discounts: the

monthly broadband service discount and the one-time device discount.

However, none of FCC’s established goals and measures address

performance of the device discount. FCC officials told us that FCC does

not plan to separately analyze performance of this aspect of ACP.

According to these officials, this is because program subscribers can only

receive the device discount from the same participating provider that they

receive the service discount from. As such, FCC officials said they believe

Page 17 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

the current goals and measures already capture the device discount as

well.

According to FCC officials, FCC has not yet fully refined its ACP

performance goals and measures because efforts to collect certain

information and data are still under way. For example, FCC officials told

us they intend to survey program subscribers to learn how ACP affected

their internet access. These officials added that the results of that survey

will then inform a broader survey of the entire country that will measure

outcomes for the general public. To conduct this broader survey, FCC

officials stated that FCC plans to request proposals from vendors with

public survey experience. According to these officials, FCC plans to use

these surveys as sources of information to refine performance measures.

The officials said there is no set timeline for implementation of these

surveys.

In the meantime, according to FCC officials, USAC conducted outreach to

a sample of ACP subscribers in September 2022 for some of FCC’s

measures, and FCC’s Office of Economics and Analytics has also begun

analyzing some data that relates to others. These officials noted that FCC

plans to establish additional targets after establishing some baselines.

FCC officials also noted that the IIJA requires FCC to issue rules on the

annual collection of information about the price and subscription rates of

internet service offerings received by ACP subscribers.

31

In June 2022,

FCC issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking requesting comments on

the data to be collected and mechanism for collecting these data. In this

notice, FCC also proposed using these data to evaluate whether the

program was achieving the established goals and asked questions about

this proposal, particularly about what information it should collect to

measure performance.

32

ACP represents a significant investment in helping consumers afford

broadband, and effective performance goals and measures could help

FCC and others gauge the program’s achievements and identify

opportunities for improvement. We acknowledge that collecting relevant

information and data can help agencies establish baselines from which to

measure progress. However, knowing what the specific goals are and

what needs to be measured should drive what data and information to

31

See IIJA § 60502(c)(1).

32

In the Matter of Affordable Connectivity Program, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, FCC

22-44, para. 12 (2022).

Stakeholders’ Views on FCC’s ACP

Performance Goals and Measures

Many stakeholders we spoke with stressed

the importance of the Federal

Communications Commission (FCC) using

quality information to evaluate the Affordable

Connectivity Program’s (ACP) performance

and said it was unclear if the performance

measures FCC had established would be

effective. Most stakeholders generally agreed

that developing more specific measures that

show what the program is achieving would be

necessary. For example, they cited metrics

detailing how many ACP subscribers are new

to ACP versus how many were already

Lifeline participants, which enrollment

methods subscribers are using, or the

program participation rate by various

demographic characteristics (such as

geography, race, age, and socioeconomic

status). Several stakeholders added that, for

various reasons, the device discount aspect of

the program has not been effective and

wanted FCC to assess this aspect in order to

help identify improvements.

Source: GAO analysis of information from stakeholders. |

GAO-23-105399

Page 18 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

collect, how to collect it, and how to balance tradeoffs. For example, it is

unclear how FCC’s planned survey measuring outcomes for the general

public will relate to ACP performance.

We also acknowledge that program subscribers must receive the device

discount from the same participating provider from which they receive the

broadband service discount. However, not all providers offer the device

discount and not all subscribers receive it. Therefore, it is unclear how

FCC’s current goals and measures will capture this aspect of the

program. Without more specific and clearer goals and measures, it is

unclear whether FCC will be able to effectively demonstrate the

program’s achievements to Congress and other stakeholders.

To raise awareness of ACP, FCC has completed a variety of outreach

activities, including (1) creating consumer outreach materials, (2)

partnering with federal agencies, and (3) engaging and leveraging other

outreach partners.

• Creating consumer outreach materials. FCC has created a variety

of outreach materials (available in English and non-English

languages) to inform eligible households about the program. FCC’s

website has several ACP consumer-focused webpages with

information about program eligibility, how to apply, and responses to

frequently asked questions (FAQ). FCC has also created a toolkit with

various items such as flyers and fact sheets available to download,

print, and distribute. These items include those intended for outreach

partners to distribute to the public and those intended for government

FCC Has Engaged in

Outreach for Its New

Broadband

Affordability Program,

but Its Language

Translation Process

and Outreach

Planning Do Not Fully

Align with Leading

Practices

FCC Has Engaged in

Various Outreach Efforts

to Raise Program

Awareness

Page 19 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

entities to use, including posters and a letter inviting eligible

households to participate. FCC can also print these items and mail

them to outreach partners across the country upon request. According

to FCC documentation, from January 2022 to September 2022, FCC

mailed almost 200,000 printed items to outreach partners to distribute

to their communities.

• Partnering with federal agencies. To raise awareness of ACP, the

IIJA requires FCC to work with the seven federal agencies

33

that

administer programs that qualify households for ACP.

34

To promote

ACP, FCC officials told us they have leveraged existing relationships

with these agencies that they developed during outreach efforts for

ACP’s predecessor, EBB. See table 3 for examples.

Table 3: Examples of FCC Partnerships with Federal Agencies to Raise Awareness for the Affordable Connectivity Program

(ACP)

Federal agency

Outreach effort(s) completed or planned

Department of Agriculture

According to FCC officials, they are working with the department to include information about ACP

in the department’s meetings with its stakeholders, who include state-level administrators of

departmental programs.

Department of Education

According to FCC officials, they worked with the department to share information about ACP with

Pell grant recipients for the 2020–2021 and 2021–2022 academic years via email. FCC officials

said they planned to replicate this effort in future years, including the 2022–2023 academic year.

Department of Housing and

Urban Development

In March 2022, FCC officials presented at a departmental webinar and gave an overview of ACP

along with best practices for engaging residents of public housing, outreach, and program

enrollment.

Department of Veterans Affairs

FCC officials stated that FCC will work with the department to provide digital consultations to

veterans to help them learn about ACP.

33

These agencies are the Departments of Agriculture (Food Distribution Program on

Indian Reservations; National School Lunch or Breakfast Programs; Special Supplemental

Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children; Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program), Education (Federal Pell Grants), Health and Human Services (Medicaid, Tribal

Head Start, Tribal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families), Housing and Urban

Development (Federal Public Housing Assistance), Interior (Bureau of Indians Affairs

General Assistance), and Veterans Affairs (Veterans Pension or Survivor Benefits), as

well as the Social Security Administration (Supplemental Security Income).

34

The IIJA requires FCC to “collaborate with relevant Federal agencies, including to

ensure relevant Federal agencies update their System of Records Notices, to ensure that

a household that participates in any program that qualifies the household for the

Affordable Connectivity Program is provided information about the program, including how

to enroll in the Program.” IIJA § 60502(a)(3)(B)(ii). FCC concluded that it does not have

the authority to compel these other agencies to do this, but directed various staff offices

within FCC to fulfill this collaboration requirement through other activities. See FCC 22-2,

para. 199.

Page 20 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Federal agency

Outreach effort(s) completed or planned

Social Security Administration

In March 2022, FCC published a guest blog post on the Social Security Administration’s website

that explained the benefits of ACP and program eligibility. According to FCC officials, the Social

Security Administration agreed to add information about ACP to media playing in its waiting rooms.

FCC officials said the Social Security Administration also included information on ACP in a “Dear

Colleague Letter,” an outreach notice the agency distributed to its stakeholders.

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Communications Commission (FCC) information. | GAO-23-105399

Note: Each of the listed agencies administer programs that qualify eligible low-income households for

ACP.

FCC officials told us they are working to formalize their relationships with

other agencies. For example, they are in the process of developing

memorandums of understanding with some of these agencies. According

to FCC officials, they have also leveraged a White House initiative to

formalize commitments from other agencies and convene cross-agency

meetings.

35

• Engaging and leveraging other outreach partners. FCC shares

information with its outreach partners—including participating

providers; state, local, and tribal entities; and advocacy groups—

through emails, monthly meetings, and other events. FCC sends

ACP-related information to an email listserv that contains over 50,000

unique email addresses as of March 2022. FCC has also hosted

monthly partner meetings to discuss program updates, and completed

a number of other events to engage its outreach partners. According

to FCC documentation, between November 2021 and September

2022, FCC completed about 400 presentations, discussions, “train-

the-trainer” events, virtual town halls, and briefings.

FCC also leverages these outreach partners’ activities to help raise

awareness of ACP. In the program’s final rules, FCC states that

outreach partners’ activities, as described below, play an important

role in raising awareness about the program.

36

Participating providers: The ACP final rules require participating

providers to publicize the availability of the program and carry out

public awareness campaigns. FCC gives providers flexibility in how to

35

In May 2022, the White House launched the website getinternet.gov to help raise

awareness of ACP and connect eligible households with participating providers that would

provide broadband service at no cost to ACP subscribers. This initiative is separate from

FCC-led outreach efforts.

36

FCC 22-2, para. 271.

Page 21 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

meet these requirements.

37

According to some industry stakeholders

we spoke with, providers have various efforts to raise awareness of

ACP, such as including flyers in utility bills, using radio and television

advertisements, or advertising online. We reviewed a selection of 20

participating provider websites for additional context on how providers

advertise ACP online and found that some of the websites did not

provide detailed information about the program and some did not

advertise ACP at all.

38

According to FCC officials, providers that do

not advertise on their websites could still be considered in compliance

with program rules if they advertise by other means, such as by mail

and customer service calls. FCC officials also said they would likely

incorporate providers’ advertising efforts into future reviews of the

program, which would help FCC identify non-compliance with the

requirement to publicize the program.

State, local, and tribal entities: State, local, and tribal entities have

also made various efforts to raise awareness of ACP. For example, in

a letter submitted to FCC, Montgomery County, Maryland, described

the 14 enrollment campaign events it held in June 2022 and noted

that the county used these events to help eligible households enroll in

ACP. Some states and cities, in collaboration with the White House,

planned to text eligible residents about the program.

39

In comments

submitted to FCC, the city of Boston described how it planned to train

volunteer tax preparers to share information about ACP with those

who qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit, since these individuals

often qualify for ACP. One tribal stakeholder we spoke with said that

some entities have partnered with tribes to communicate with tribal

elders and used other “on the ground” efforts to raise awareness.

37

FCC 22-2, para. 205, 207. The IIJA requires the public awareness campaign. (IIJA

§ 60502(3)(B)(ii)). The ACP final rules state that participating providers must publicize the

availability of ACP in a manner reasonably designed to reach consumers likely to qualify

and in a manner that is accessible to individuals with disabilities. FCC does not prescribe

specific forms of outreach that providers must use but does establish that providers must

collaborate with state agencies, public interest groups, and non-profit organizations on

public awareness campaigns and provides other guidance.

38

At the time of our review, according to FCC data, 10 of the providers we selected

accounted for nearly 80 percent of the program’s subscribers.

39

In May 2022, the White House announced it was partnering with two states

(Massachusetts and Michigan) and three cities (Mesa, Arizona; New York City; and

Philadelphia) to text millions of eligible households about ACP.

Page 22 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Advocacy groups: Advocacy groups have also conducted a variety of

outreach efforts. For example, ACP Para Mi (ACP For Me) is a

nationwide partnership of local and national Latino organizations and

community leaders working to raise awareness for the program by

serving as a bilingual resource hub. This partnership provides

outreach content in English and Spanish, along with a step-by-step

guide for community advocates to help families navigate the ACP

enrollment process. The National Digital Inclusion Alliance, a nonprofit

focused on digital equity, published an extensive FAQ resource on its

website, and hosted a webinar titled “What You Need to Know about

the FCC Affordable Connectivity Program.”

FCC has translated ACP outreach materials into non-English languages,

but we found that the m

aterials did not always align with leading practices

for consumer-oriented content.

40

Specifically, FCC translated some of its

outreach materials (including webpages and items from its outreach

toolkit) into multiple non-English languages for use by individuals with

limited-English proficiency.

41

FCC employed an original translation

process used for materials it distributed when ACP launched and later

began updating this process in September 2022. In reviewing a selection

of the materials in five of the non-English languages (Chinese,

42

French,

Korean, Spanish, and Vietnamese), we found that the translations were

not always clear and accurate or complete (compared to the English

materials). We also found the translated materials did not always include

elements that make them practical or help manage users’ expectations

(such as directing a user to additional assistance or indicating when a

user will navigate to an English-only area). See figure 3 and the

discussion below.

40

U.S. Digital Service, Digital Services Playbook; U.S. Web Design System, Design

Principles; and General Services Administration, Top 10 Best Practices for Multilingual

Websites.

41

The ACP consumer-oriented webpages are available in Chinese, Korean, Spanish,

Tagalog, and Vietnamese. Items from the outreach toolkit are available in Arabic,

Chinese, French, Haitian-Creole, Korean, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, and

Vietnamese.

42

The ACP webpages were translated into Traditional Chinese, while the outreach toolkit

items were available in both Traditional and Simplified Chinese, a form of written Chinese

where traditional Chinese characters have been simplified. We reviewed the webpage in

Traditional Chinese and toolkit items in Simplified Chinese to ensure coverage of both

forms of Chinese. For more detail, see appendix I.

FCC’s Language

Translation Process and

the Resulting Non-English

Program Outreach

Materials Do Not Fully

Align with Leading

Practices

Clarity

and

accuracy

Completeness Practicality

Managing

users’

expectations

Leading

practice

D

i

r

e

c

t

i

o

n

s

:

H

o

v

e

r

o

v

e

r

i

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

p

r

a

c

t

i

c

e

t

o

v

i

e

w

d

e

t

a

i

l

s

.

Figure 3: Selection of FCC’s Chinese, French, Korean, Spanish, and Vietnamese Affordable Connectivity

Program (ACP) Outreach Materials Compared with Leading Practices for Consumer-Oriented Content

To access a printable version of this interactive graphic, see appendix III.Print instructions

Page 23 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Interactive graphic

Page 24 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

• Clarity and accuracy. According to leading practices for consumer-

oriented content, outreach materials should be written in clear, easy-

to-follow language that is factually accurate, and federal documents

should be identifiable as a federal product. We found that the Spanish

and Chinese materials were clear and easy to understand, but some

other non-English materials reviewed were difficult to understand. In

particular, we found clarity issues in the Korean and Vietnamese

materials. In the Korean content, we consistently found grammatical

errors, spacing issues (which, in the Korean language, may confer

incorrect or different meanings), and mistranslations that inadvertently

changed the meaning of the text.

43

We also found that the

Vietnamese webpages read as though they had been generated by a

machine translation, as they read unnaturally and were difficult to

parse.

Additionally, in most of the non-English materials we reviewed,

accurate information was conveyed; headings, images, and links were

accurately labeled; and hyperlinks functioned properly. However, we

also found some instances where inaccurate information could

confuse a user. For example, one response to a question on the

Korean Consumer FAQ webpage stated that households on tribal

lands may receive up to $70 (rather than $75) per month off their

broadband service, which is correctly listed elsewhere on other

Korean materials. In another instance, the Korean ACP main

webpage conveyed that the participating provider (rather than the

household) must contribute between $10 and $50 toward the

purchase of the device. The Spanish Consumer FAQ webpage

repeated the same question twice and listed a different response to

the question each time. We also found that a Spanish social media

image included English text. See figure 4 for these examples.

43

Korean relies on correct spacing to convey specific grammatical constructs, thus

missing or incorrect spacing in written Korean can create confusion in meaning.

Page 25 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Figure 4: Examples of Duplicated Spanish Text on FCC’s Spanish Version of the

Affordable Connectivity Program Consumer FAQ Webpage and English Text on

Spanish Social Media Image

Page 26 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

• Completeness. Leading practices for consumer-oriented content call

for the content on non-English materials to match the content on the

English materials. We found that the content on the non-English

outreach toolkit items generally matched their English counterparts.

However, we also found that all of the non-English ACP main

webpages were missing information. Most lacked hyperlinks to the

FCC’s Complaint Center (where consumers can file an informal

complaint about ACP) and to the Consumer FAQ webpage.

44

The

non-English ACP main webpages were also missing information on

upcoming events and, in some cases, were missing the phone

number for the ACP Support Center. Consumers can call this center

to learn about the status of their application, documents needed to

prove eligibility, and participating providers that service the caller’s

area.

In addition, the leading practices describe the importance of

consistent maintenance of non-English content compared to its

English version. This allows users of both versions to have a

comparable experience. We found that FCC delayed updating the

non-English ACP main webpages. While the English version of this

webpage was updated in March 2022, the non-English versions had

not been updated since January 2022.

• Practicality. According to leading practices, consumer-oriented

content should be practical, allowing users to easily understand and

complete key tasks and directing users to additional assistance. We

found that all of the non-English materials we reviewed contained

information to direct users to begin the application process, such as

by listing instructions or directing users to the ACP website. However,

although many of the non-English materials also included the ACP

Support Center phone number, they did not disclose that callers could

receive assistance in other non-English languages. In fact, FCC

44

According to FCC officials, not linking to the center was a deliberate choice, as it is only

available in English. However, consistent with leading practices, in some other parts of its

non-English webpages, FCC included an indicator signaling when a user would navigate

to an English-only area.

Page 27 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

officials told us that callers can receive assistance in up to 200 non-

English languages via a third-party translator service.

45

• Managing users’ expectations. With respect to online content,

leading practices for consumer-oriented content state that the website

maintain users’ expectations on non-English websites by indicating

when a user will navigate to an English-only area. We found that the

Spanish webpages sometimes included a parenthetical en inglés (in

English), but the other non-English webpages did not disclose when

hyperlinks led to content in English.

FCC’s original translation process for producing these non-English

outreach materials varied slightly based on the target language. FCC

primarily used an internal (or, “in-house”) staff translator for Spanish

translations and a language translation contractor for other non-English

languages, as well as for Spanish when the staff translator was not

available. See figure 5.

45

FCC officials told us that callers may request to speak with a Spanish-speaking agent.

The other non-English languages are supported via a language service, which a caller

may request once connected to an agent. They added that, if an interpreter is available,

the interpreter joins the call and translates the conversation in real time. If an interpreter is

unavailable, the caller can leave a message, which could be translated and addressed

once an interpreter is available. FCC officials said that it is common for this type of service

to function this way.

Stakeholders’ Views on the Quality of

FCC’s Non-English ACP Outreach

Materials

Many stakeholders we spoke with stressed

the importance of non-English, culturally

competent outreach materials. Some said that

the Federal Communications Commission’s

(FCC) Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP)

translations were ineffective. For example,

one stakeholder that advocates for

populations with limited-English proficiency

said that FCC’s translated materials were so

poor that the group produced its own.

Furthermore, when the program launched as

ACP after the initial launch of the Emergency

Broadband Benefit program (EBB), some

stakeholders said the quality of the translated

materials had not improved, even though one

group had worked with FCC to improve

translated EBB materials. One stakeholder

said that FCC published ACP materials in

Portuguese, but labeled them as Spanish.

The stakeholder said FCC quickly remedied

the issue.

Source: GAO analysis of information from stakeholders. |

GAO-23-105399

Page 28 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

Figure 5: FCC’s Original Translation Process for Creating Non-English Affordable Connectivity Program Consumer Outreach

Materials

According to FCC documentation, under this original process, FCC’s

contractor had two quality assurance controls for translation tasks. First,

translators were required to meet certain language proficiency

requirements. FCC officials told us that they received documentation to

verify that translators met these requirements. As a second control,

FCC’s translation contract stated that the contractor would have at least

two native language or proficient individuals collaborate and review the

accuracy of each translation task assigned. According to FCC officials,

Page 29 GAO-23-105399 Affordable Broadband

FCC did not receive documentation that the contractor had completed this