$

$

Wisconsin Guide to Implementing

Career-Based Learning Experiences

2

This publication is available from:

Division of Academic Excellence

Career and Technical Education Team

dpi.wi.gov/cte

January 2022

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

Jill K. Underly, PhD, State Superintendent

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction does not

discriminate on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, creed,

age, national origin, ancestry, pregnancy, marital status or

parental status, sexual orientation, or ability and provides

equal access to the Boy Scouts of America and other

designated youth groups.

Contents

Acknowledgements...................................................... 3

Foreword ................................................................ 3

Opening Letter........................................................... 4

Purpose .................................................................. 4

Background ............................................................. 5

Bringing It All Together:

Connecting CBLEs to Career Readiness Programs ...................... 7

Work-Based Learning Program Accountability .........................8

Building a Quality Local Work-Based Learning Program ...............11

Legal Considerations ...................................................16

Equity and Access.......................................................21

Types of Career-Based Learning Experiences ..........................23

References..............................................................42

Appendices .............................................................42

3

Acknowledgements

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI) would like

to recognize and thank the individuals and organizations that have

contributed to the development of the Wisconsin Guide to Implementing

Career-Based Learning Experiences.

Specic content contributors include:

• James Chiolino, Deputy Division Administrator and Director, Labor

Standards Bureau, Equal Rights Division, Wisconsin Department of

Workforce Development (DWD)

• Matthew White, Director, Bureau of Investigations, DWD

• Heather Curnutt, Attorney, Ofce of Legal Services, DPI

Special thanks to Amanda Langrehr, Career Exploration and Planning

Director, and Jessica Sloan, Director of Instructional Services, both from

CESA 4, for their research, focus group outreach, and writing. Also, the

guide would not have been possible without the funding provided by the

J.P. Morgan Chase New Skills for Youth 2017-2019 grant.

Foreword

Welcome to the Wisconsin Guide to Implementing Career-Based Learning

Experiences. This guide describes the wide variety of career-based

learning experiences, including work-based learning experiences, that

Wisconsin school districts may offer as part of their Academic and

Career Planning (ACP) programming.

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s understands the

need for schools to help students explore where life will take them

after graduation, and the challenges that accompany that process.

ACP programming makes it possible for Wisconsin students learn about themselves and

potential careers while also integrating into academic classroom instruction.

Career-based learning experiences (CBLEs) are uniquely positioned to bring a student’s

career exploration into focus and to give students a deeper understanding of the world of

work. A CBLE might act as a bridge between academic instruction and career programming

by inviting a career speaker to talk about construction, job shadowing with a local doctor,

or pursuing an internship at an area computer business. Whatever form it takes, embedding

CBLEs into a district’s ACP programming provides students with experiences they need to

make informed decisions about their future career.

CBLEs offer benets beyond career planning, such as improving student motivation and

attendance. Career and technical education can increase graduation rates by an average

of 10 percent, and it is especially important for students who nd it difcult to engage

successfully in school. CBLEs offer students the opportunity to put all the pieces of their

education together, and to see the purpose that all this preparation offers them for post-

secondary endeavors. In addition, not all students have adult mentors to help explore

careers. CBLEs offer a school-supervised, safe way for students to interact with adult

mentors at a crucial time in their lives.

As educators, we must be intentional about identifying and addressing the barriers

preventing our students from fully participating in experiential learning. Addressing these

barriers will help ensure that all students have fullling work lives and that Wisconsin’s

businesses and community organizations have the talent needed to drive our economy and

support our communities.

I encourage K-12 teachers and leaders to use this guide to implement or enhance career-

based learning experiences in their schools and districts.

Jill K. Underly, PhD

State Superintendent

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

4

Purpose

The purpose of this guide is to describe the most common career-based

learning experiences (CBLEs) available to students and teachers in

Wisconsin schools. CBLEs, such as classroom speakers, company tours,

and job shadows, familiarize students with the nature of jobs and help

them determine the general direction they want to take their learning and

possibly their careers.

In addition, this guide will assist educators and employers differentiate

between CBLEs and work-based learning opportunities (WBLs). A

subset of CBLEs, WBLs include experiences such as internships, Youth

Apprenticeships, and cooperative education programs. High-quality WBLs

allow students to experience work environments, learn new skills, build

a career identity, and better chart a path to and through postsecondary

education and training that aligns to their career goals.

The hands-on nature of most WBLs also helps young people develop

employability skills. These include forming positive relationships with

adults, developing social capital, and building networks within their career

pathway. Employability skills are assets that benet students beyond high

school, regardless of the career pathway they choose.

Finally, this guide provides school districts with the detailed criteria needed

to ensure the WBLs they offer fulll the reporting requirements of the

federal Perkins V legislation.

“[Work-based

learning] is a

vital part of

our students’

education

journey. This is

an opportunity

to nd out if they

like or do not like

things in their

career path.”

—Cheryl Kothe

Retired from

Kenosha Unied

School District

$

$

Amy Pechacek

Secretary-designee

Wisconsin Department of

Workforce Development (DWD)

Melissa Hughes

Secretary and Chief Executive Ofcer

Wisconsin Economic Development

Corporation (WEDC)

Opening Letter

Wisconsin has long been recognized nationally for the education of our youth for

future success. Preparation for academic, college, career, and life readiness is part of

the vision of “every child a graduate, college and career ready” with the knowledge,

skills, and habits to succeed after graduation. The Academic and Career Planning (ACP)

process, implemented statewide in 2017, further reinforces the importance of a school-

and community-supported delivery system. ACP assures that students connect their

classroom learning to information, experiences, and opportunities, assisting them and

their families in making decisions about next steps after graduation.

As part of ACP, a major component of college and career awareness, exploration, and

planning includes access to career-based and work-based learning experiences for

students while still in school. The guide provides educators, students, families, and

community members with information necessary to navigate the often confusing mix of

available programs and offers links to specic programs or recommended resources.

Working in partnership with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI),

the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development (DWD) and the Wisconsin

Economic Development Corporation (WEDC) recognize the importance to Wisconsin’s

future of connecting and supporting youth talent development through these

experiences.

The school community, which works directly with families, Wisconsin businesses, and

community members, is a critical part of a student’s life and directly impacts their

success and growth as students mature and transition into their next steps. Our state

agencies continue to collaborate and cooperate through these efforts to provide

students the chance to realize their goals.

5

Background

Through the Academic and Career Planning (ACP) process, students

participate in a variety of career-based learning experiences (CBLEs) that

involve direct employer engagement. The engagement between employers

and students may be short, as with classroom speakers, or may be in-depth,

as with Youth Apprenticeship, but all CBLEs include participation from an

employer or industry partner and are generally school-supervised.

Wisconsin Career-Based Learning Experience Continuum

KNOW CBLEsEXPLORE CBLEs PLAN & GO CBLEs

Classroom speakers

Company tour

Career fair

Career-related

project

Part-me or

summer job

Job shadow

CTSO or

career-related

out-of-school acvity

Career-related

volunter or service

learning

Informaonal interview

Career mentoring

School-based enterprise (SBE)

Student entrepreneurial

experiences (SEE)

Simulated worksite

Internship or local co-op

State-cerfied co-op program

Supervised Agricultural

Experiences (SAE)

State-cerfied Yo uth

Apprenceship

ACP ACTIVITIES

Lessons, acvies, and

soware tools that guide

K-12 students through the

ACP process.

They can take place in the

classroom, out of school, or

virtually, but do not involve

employer engagement.

CAREER-BASED LEARNING

EXPERIENCES

An ACP acvity that involves

a business or employer

partner.

ACP PROCESS

ACP COMPONENTS

KNOW

Who am I? Get to know your interests, skills, and

strengths.

EXPLORE

Where do I want to go? Explore careers and

educaonal opportunies.

PLAN

How do I get there? Set your career, educaon, and

financial goals. Choose courses and acvies to

further develop the academic and technical skills

you will need.

GO

What support do I need to succeed? Idenfy

resources and supports that will help you achieve

your plan. Develop success skills.

It is important that districts offer a continuum of CBLEs as students

progress through the stages of the ACP process. We recognize that the

CBLE continuum may not include every possible type of CBLE. Further,

CBLEs may look slightly different in each school district to best meet

the needs of local students and employers. Regardless, we encourage all

Wisconsin educators to embrace these CBLE terms in order to build a

common language among educators and employers.

Career-based learning experiences (CBLEs) – These include the universe

of business-connected experiences and opportunities that allow K-12

students to participate in career awareness, career exploration, or career

development.

Work-based learning experiences (WBLs) – WBLs are a subset of CBLEs

that meet the quality and rigor requirements for career and technical

education (CTE) as dened in the federal Strengthening Career and

Technical Education for the 21st Century Act (Perkins V).

Table 1. Career-Based Learning Experience Types*

EXPERIENCE TYPE

1. Classroom speaker CBLE

2. Company tour CBLE

3. Career fair CBLE

4. Career-related project CBLE

5. Part-time or summer job CBLE

6. Job Shadow CBLE

7. Career-related volunteer or service learning CBLE

8. Career and technical student organization (CTSO) or Career-

related out-of-school activity

CBLE

9. Informational interview CBLE

10. Career mentoring CBLE

11. Simulated worksite CBLE or

WBL

12. School-based enterprises (SBE) CBLE or

WBL

13. Student entrepreneurial experience (SEE) CBLE or

WBL

14. Supervised agricultural experience (SAE) CBLE or

WBL

15. Internship or local co-op CBLE or

WBL

16. State-certied employability skills co-op WBL

17. State-certied occupational program co-op WBL

18. State-certied youth apprenticeship WBL

*Table 1 lists the category most often assigned to a specic experience.

Note that some CBLEs may be counted as WBLs, depending on how closely an

experience ts within the parameters of the Perkins V denition.

6

For the purposes of state reporting, DPI follows the federal Strengthening

Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act (Perkins V)

legislation denition of work-based learning. Therefore, for a school district

to report a CBLE as a WBL, the CBLE must meet the following criteria:

1. Involves sustained interactions, either paid or unpaid, with industry

or community professionals.

Sustained: This means a minimum of 90 hours that can be rotated

among employers or positions. The employer is engaged throughout

the experience, which can take place in one semester, an entire year,

the summer, or even a six-week period. Note: There are exceptions

in which the 90 hours could be spread over multiple years for some

special populations, such as for vocational training in postsecondary

transition planning (PTP) for students with disabilities.

Interactions: This means more than just observing; WBL is

performance-based.

2. Takes place in real workplace settings as practicable or simulated

environments at an educational institution.

3. Fosters in-depth, rsthand engagement with the tasks required in a

given career.

4. Aligns with a course (minimum one semester). Providing credit for

both the work-based learning experience and the course is highly

encouraged.

5. A training agreement between the student, employer/business,

and school denes the roles and responsibilities of the student, the

employer, and the school. (See Appendix 1.)

6. There are regular, periodic oversight and interactions with employers

or community members from the industry related to the assigned

work.

Two accountability standards—the Perkins V performance measure and

School and District Report Cards—rely on districts to accurately report

WBLs that meet all six criteria.

Because experiential learning is delivered primarily outside the local

school district, it is important for the local school to work closely with the

community organization or work-based mentor to establish policies and

procedures. Students, schools, parents, community-based organizations,

and employers are required to follow all state and federal child labor

regulations (if applicable) pertaining to WBL programs.

A student is released from

school to go to a job for one

period a day as part of the

school district allowance for

the at-risk credit recovery

program. The student

independently nds the job, which has no connection to

classes taken at school or supervision by school staff. The

student receives no class credit for leaving and working, and

works hours set by the employer.

To turn it into a CBLE

• Assist the student in nding a job that connects to the student’s

ACP plan.

• The focus of the work experience can be on developing skills relat-

ed to a potential career area of interest or learning about careers

that may be of interest.

To turn it into a WBL:

• School partners with the employer to mentor the student.

• School supervises the experience and ensures the employer-

mentor provides a mechanism for skill attainment and reection

according to the DPI State-Certied Employability Skills program.

• School, employer, and student ensure a minimum of 90 hours of

paid work occurs as required by the Employability Skills program.

• Release period is classied as a course with high school credit.

Note: All six WBL criteria still need to be met.

CBLE vs WBL?

7

Bringing It All Together:

Connecting CBLEs to Career

Readiness Programs

Now that we understand what a CBLE is, let’s look at how CBLEs relate to

the larger components of an integrated career readiness program.

Academic and Career Planning (ACP)

In Wisconsin, the ACP process bridges academic classroom learning

with the steps needed to identify a potential career choice. Through

ACP, students set goals to dene their interests, skills, preferences, and

aspirations. As they learn more about themselves, students are better able

to recognize career possibilities and educational pathways that match

their interests. In addition, ACP enables students to explore their career

preferences and learn if a career is compatible and worth pursuing. In fact,

exploring careers through CBLEs is a critical component of ACP. These

experiences connect academic coursework to career opportunities in

school, at a workplace, or in partnership with business mentors.

Learn more more about Academic and Career Planning on the DPI website.

CBLEs provide students with a rsthand look at:

• what careers are like,

• how school-based learning is relevant,

• what skills are needed, and

• how they can use their skills in a real-world setting.

Most importantly, students can evaluate how interested they are in a given

career and adjust their plans accordingly.

Career Pathways

For many students, the ACP process leads naturally to a career pathway.

In K-12 education, a career pathway is a series of connected career and

technical courses and training opportunities that ow seamlessly into a

post-high school education for a specic career area. A career pathway

includes:

• A sequence of career and technical education courses

• An industry-recognized credential

• Work-based learning experiences

• Opportunities to earn college credit at the high-school level

• Related career and technical student organization activities

For districts that offer a career pathway for high school students, it is

critical that they also offer CBLEs related to the pathway starting in middle

school, if not earlier. Because CBLEs are highly engaging, they are the

best way to get students excited and interested in careers, and are most

effective at creating a pipeline into a high school career pathway program.

In addition, for students participating in a career pathway program, CBLEs,

particularly WBLs, are a key way to develop skills for the pathway. Students

who participate in CBLEs in earlier grades are more likely to have successful

experiences in WBL placements later on.

8

Academic Courses

Further, connecting the classroom to careers is an effective way to engage

students and reinforce educational relevance. CBLEs, such as a guest

speaker, a career-related project, or a virtual job shadow, can help students

see how their learning can be applied in a variety of careers, often igniting

an interest and passion for learning that would not exist otherwise. It helps

answer the eternal student question, “Why do we need to know this?”

Because of this, every student is encouraged to participate in at least one

CBLE every year as a part of the ACP process.

Xello

In many regions of the state, students can access CBLE opportunities

through Xello, the state-supported ACP software tool. Often referred to as

“Inspire,” companies create proles in Xello that can include CBLE or WBL

“opportunities” they offer. Educators and students can request to engage

with companies in their desired CBLE or WBL directly through their Xello

account. To learn more, go to Xello.

Out-of-School-Time Programs

Although many CBLEs take place during the school day, out-of-school-time

programs should play an important role in providing CBLEs and WBLs for

students. We encourage school districts to partner and collaborate with

out-of-school-time programs, such as community learning centers, pre-

college programs, libraries, youth workforce development programs, and

other youth-serving organizations. These programs can support CBLEs and

WBLs, and enhance your ACP program.

Social and Emotional Learning

As previously mentioned, CBLEs help students develop stronger

employability skills. And many employability skills, such as communication,

collaboration, and critical thinking, are based on social and emotional

competencies. Thus, CBLEs are an ideal way for students to practice and

develop these skills. Learn more about this connection in “Wisconsin’s

Guide to Social and Emotional Learning and Workforce Readiness: A

Powerful Combination.”

Work-Based Learning

Program Accountability

Student participation in WBL programs is a metric that is used for state

and federal accountability. For state accountability, it is an indicator of

postsecondary preparation. For federal accountability, WBL serves as

the additional quality indicator chosen by Wisconsin as outlined in the

Wisconsin Perkins V State Plan. Specically for federal reporting purposes,

the denition is as follows:

5S3: Work-based Learning Participation

Denition: The percentage of CTE concentrators* graduating from high

school having participated in work-based learning.

*A CTE concentrator is a secondary student who has completed (passed) at least

two CTE courses in a single career pathway throughout high school.

As a result, the program quality indicator relies heavily on WBL data

collected under the larger Career Education data collection in Wisconsin’s

Information System for Education, otherwise known as WISEdata. WBL

data collected under Career Education is used to satisfy both Perkins V data

reporting requirements and college and career readiness accountability.

Under Career Education, WBL may be reported as either a certied or non-

certied career education program.

Districts should determine and map their WBL experiences with a certied

or non-certied career education program based on the career education

program name denitions. Once identied, districts should report the

appropriate program names and students associated with the programs in

their individual student information system (SIS). To help districts determine

if and how they should be reporting WBL using certied or non-certied

career education program names, please refer to the owchart on the next

page.

9

DPI has established a set of recommended School Courses for the Exchange

of Data (SCED) course codes for WBL experiences. Districts submitting WBL

data at a course level are strongly encouraged to use these codes for their

WBL courses to ensure accurate and consistent data at the state level for

WBL accountability reporting.

The suggested state or SCED codes are based on the National Center for

Education Statistics (NCES) SCED rigor level definitions as follows:

Rigor Level Use for the Following Experience:

General/regular

• Local internships and co-ops

• State-certied Employability Skills

Co-op

• CBLEs (SAEs, SBEs, SEEs,

volunteering, simulated worksites,

entrepreneurial businesses) that

qualify as WBLs under the quality

criteria outlined in the Denitions

section

Advanced

•

Youth Apprenticeship, Year 1

• State Co-Op, Year 1

Honors • Youth Apprenticeship, Year 2

10

Students participate in a classroom to learn how to

build sheds for the community. The CTE-licensed

teacher provides training, management of daily tasks,

and assessments of learning as part of the high school

elective course. (CTE Course)

To turn it into a CBLE:

A CTE course can become more connected to industry as a CBLE by incorporating regular

interactions and training with industry construction professionals, including classroom

speakers, worksite visits, mentoring, and certication training.

To turn it into a WBL:

School-Based Enterprise (SBE):

• The teacher ips the class around and acts as a facilitator “CEO,” setting up the class

with regular employer mentorship and interaction to run the shed-building as a business.

• The students lead in various business-dened roles for shed-building, such as order-

taking, building, quality control, and marketing.

• Students are mentored and trained by employers as part of running the business.

• Monies from the sale of the sheds go to the school for maintaining and operating the

business according to quality SBE program principles.

Entrepreneurial Business:

• A student or group of students starts their own business to build sheds with an employ-

er-mentor.

• There is a progressive outline of tasks and a training agreement between the employer

mentor, school, and student(s).

• The school ensures that the student business follows quality principles of business op-

eration and provides credit for the experience.

• Monies from the sale of the sheds are part of the

business model.

When WBL is incorporated into a classroom, time spent learning must be separated from

time spent working (even if it is work simulation). A student must log at least 90 hours of

working to count as a WBL experience. Some courses, especially year-long courses, may

include 90 hours of work directly into the class period and still have adequate time for

learning. In shorter courses, students may need to work some hours outside of class to

meet the 90-hour minimum. Thus, some students may participate in the full WBL experi-

ence while others will qualify for a CBLE. These conditions may determine whether you

report WBL as a course or as a student characteristic (see page 8).

Note: All six WBL criteria still need to be met.

In addition, please note the following for WBL SCED coding parameters

when structuring data accountability settings:

• Use the recommended WBL SCED codes only for the student’s

workplace experience portion, not the related classroom instruction

courses.

• Select the appropriate SCED code from the designated rigor level (see

columns) and cluster/career pathway (see rows) in the Work-Based

Learning (WBL) Roster Coding Chart, which can be found under the

Training, Support, and Documentation Links section of the Career

Education Help page.

• If one of the CBLE types in Table 1 is considered a WBL experience

because it meets the quality criteria, then code it as “General/regular,”

but only if it meets the denition for a WBL experience as detailed in

the “Denitions” section.

• The recommended WBL SCED codes, with the exception of

Employability Skills, are already encoded as CTE courses.

DPI continuously makes revisions and improvements for assistance with

SCED coding and program data denitions. Please stay informed.

“Work-based

learning is sustained

interactions

with industry

or community

professionals in real

workplace settings

... that foster in-

depth, rsthand

engagement with the

tasks required in a

given career eld.”

—Strengthening Career

and Technical Education

CBLE vs WBL?

$

$

11

Building a Quality Local

Work-Based Learning

Program

A national review of WBL literature reveals one common nding:

experiential learning works! Research has shown that tying classroom

curriculum to the real world through WBL helps students make the

connection between relevant learning and future careers.

In particular, work-based learning programs can provide:

...personal, educational, and career-related benets to learners as well as

to employees in the businesses who participate in these programs (Taylor

2001). Engagement in their own learning through personal involvement

in the real-life activities at the worksite, resilience developed by learning

to work independently and with others to solve problems that have

a number of viable solutions, and success in applying academic and

technical knowledge in the workplace serve to increase student self-

condence and motivate them to pursue learning (Luft 1999; Taylor

2001).

Strong partnerships with business and industry enable students to

learn about careers and the workplace and gain job-related skills.

They help students become personally aware of the standards that

employers expect and lead them to reect on the in-school learning that

complements the achievement of those standards (Brown 2003)…

Work-based programs are linked to career-themed pathways through

community college and four-year programs. Many students drop out

of high school and college programs in part because they are unable to

see any connection between what they are learning and what they may

one day be doing professionally. They ask, “Why do I have to learn this?”

By linking student learning to career pathways, work-based learning

programs can lower the dropout rate (NAF, 2011). Indeed, research has

found that students in work-based learning programs complete related

coursework at high rates and have higher attendance and graduation

rates than those not enrolled in such programs (Colley & Jamison, 1998).

(Rogers-Chapman, Felicity, and Darling-Hammond 2013)

Quality WBL programs are built around a series of activities that exceed a

stand-alone career exploration experience. Implementation of this approach

must consider the following quality components:

School-based Learning

• Career development through the district Academic & Career Planning

(ACP) process

• Identication of a career pathway

• Integration of academics and CTE

• Evaluation systems

• Secondary/postsecondary partnerships

Work-based Learning

• Employability skills development

• Work experience

• Workplace mentoring

• Technical competency

• Instruction in all aspects of an industry

Connecting Activities

• Matching students with employers/mentors

• Student mentoring programs

• Recruitment of employers

• Community and employer relations

Benets

As mentioned, there are many benets to be realized by all stakeholders

involved in WBL experiences (Iowa Department of Education 2017;

Nebraska Department of Education 2019; Tennessee Department of

Education 2017).

“There is not a

better method to

prepare students

for what is beyond

this school.”

—Harley Greisbach,

Shiocton High School

$

$

12

For students, participating in a WBL experience can:

• Connect classroom learning to the real world

• Offer a chance to observe professionals in action

• Help to network with potential employers

• Understand the connection between school, postsecondary

education, and career goals

• Practice professional behaviors with professional expectations

• Develop good work habits

• Develop leadership skills and a sense of responsibility

• Practice technical skills in real-world scenarios

• Solve problems cooperatively and creatively

• Access opportunities for economic and social prosperity

For schools and educators, WBL program partnerships provide

opportunities to:

• Hear information directly from industry professionals that enriches

classroom experiences

• Add career training techniques used in businesses

• Develop ongoing relationships with the business community

• Stay informed of industry trends and changes in workplace

expectations

• Promote skills that support student ACP goal attainment

• Ensure students are ready and prepared to meet the needs of the

labor market and postsecondary education

For employers and the community, mentoring in WBL programs can:

• Shape a pipeline of knowledgeable, motivated talent

• Increase brand awareness and loyalty

• Gather input on the next generation of workers

• Build strong relationships and lasting partnerships that benet

everyone

• Broaden community impact and contribution

• Support strong learning experiences for students

• Provide students with exposure to opportunities outside their

immediate environments

• Increase visibility of the industry/business

• Provide access to young workers who are eager to learn and have

interest in the profession

• Address future hiring needs in a cost-effective and timely manner

• Provide input on classroom curriculum

• Offer a chance to shape skills, expectations, and habits of youth

Implementing Quality Work-Based Learning Experiences and Programs

No matter which experiences are offered (CBLEs or WBLs), successful

quality career-based learning experiences are rooted in a system that

embraces collaboration, communication, and continuous improvement.

Crafting experiential learning is not a one-time activity, nor can it be

accomplished in educational silos. Educators must work collaboratively with

industry and community leaders to develop lasting partnerships that benet

everyone.

The following quality components should be represented in any WBL

program. However, given the numerous and competing priorities that

constrain a single school district, it is recommended that districts connect

By acting as the conduit between our education and business part-

ners, we create continuity in the quality of CBLEs [career-based

learning experiences] offered. Our school and business partners

understand that providing these quality experiences for students

adds direct application and value to what the students are learning

in school, which helps prepare the future workforce.

— Nikki Kiss, Former Executive Director, INSPIRE Sheboygan County

“

“

$

$

13

with each other across counties and regions to identify an intermediary to

leverage common goals for implementing and providing quality WBLs that

involve the greatest number of students.

In order to realize benets, WBL programs must support quality

experiences that foster career exploration and skills-based learning. High-

quality WBLs provide structured learning opportunities and authentic

experiences. By interacting directly with employers and businesses in

workplace settings, students are able to adapt to current academic,

technical, and employability skills in a new setting.

More specically, a local or regional WBL program of quality features

the following (Nebraska Department of Education 2019, Tennessee

Department of Education 2017):

• Is part of an overall continuum of experiences that provides students

with meaningful career development opportunities

• Is part of the school’s instructional ACP programming, not an add-on

or extra-credit activity

• Focuses on applied learning in preparation for postsecondary

education and careers

• Includes predesigned experiences that connect to the student’s ACP

• Is broad enough to ensure exposure to multiple careers within a

career pathway

• Offers regular interaction with professionals from industry

• Is supervised by both teachers and employers

• Offers opportunities for reection and feedback

• Is aligned with postsecondary and career opportunities regionally or

statewide

• Requires documentation of learning through skill assessment,

artifacts, and/or portfolios

To implement quality experiences and programs, it is recommended

that districts and regions consider the following components to ensure

successful delivery (Nebraska Department of Education 2019, Tennessee

Department of Education 2017):

• Procedures for program and student participation, management, and

evaluation

• Student recruitment and selection processes that do not create

obstacles to equitable access by special populations

• Employer selection, recruitment, and training for youth mentorship

and legal considerations

• Employment preparation protocols for students

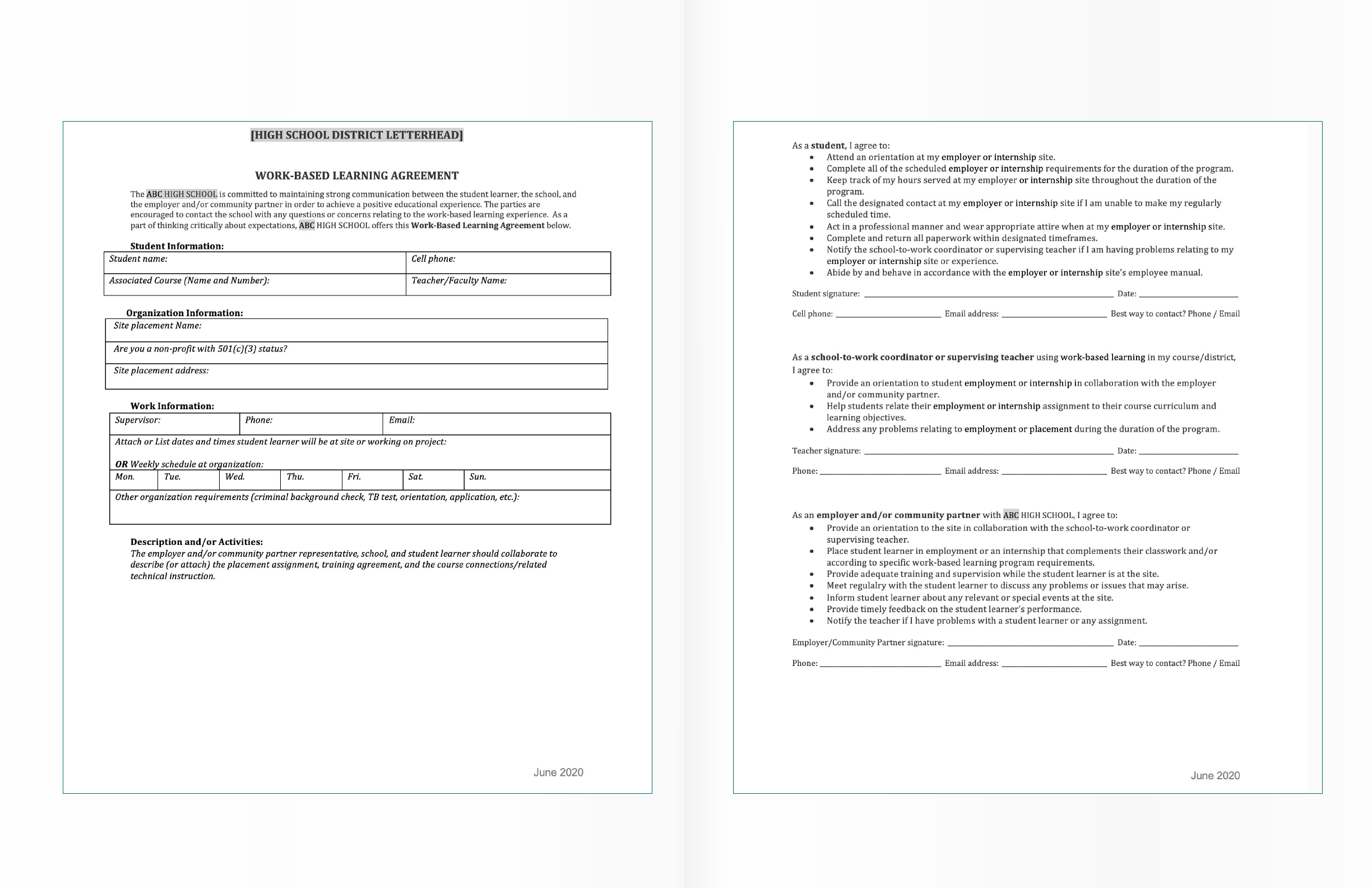

• Training agreements for students, school, employer, and adult family

members to sign (see Appendix 1)

• Resources for student reection, documentation, and feedback

during the course of the WBL experience

• Outlines of training and instruction that will occur on the job,

including required safety instructions (see Appendix 2)

• Support services to assist all youth in employment, but particularly

youth with disabilities or disadvantaged youth, for employability and

transportation

• Related instruction that helps students develop appropriate worksite

skills and behaviors, and reinforces aspects of learning that occur at

the worksite

• Collection and analysis of student and employer follow-up

information to make program improvements

• Informational and promotional materials, access to community

resources, and communication with the media to publicize program

events and accomplishments

• Engagement with employers in other CBLEs to promote greater

industry involvement

• Engagement with families that seeks feedback and promotes the

program

• Connections with other groups and agencies for resources:

Department of Workforce Development, the Division of Vocational

Rehabilitation, regional workforce development boards, regional

economic development organizations, county services, chambers of

commerce, and other organizations

• Encouragement of active participation of students in career and

technical student organizations at the local, state, and national

levels, as appropriate, including leadership and competitive skill

events

“Career exposure

and experiences

help students

determine the best

path ... by explor-

ing interests and

allow[ing] students

to build important

employability skills.

In turn, there is a

return on invest-

ment for employers

when they engage

our students in

WBL experiences.”

—Amie Farley,

Elmbrook School

District

$

$

14

Roles and Responsibilities

An effective WBL program involves the active participation of many

partners (Iowa Department of Education 2017; Tennessee Department of

Education 2017).

SCHOOL DISTRICTS AND ADMINISTRATORS

• Provide DPI-licensed teacher-coordinators who work with students,

their families, community organizations, and employers to implement

a quality WBL program.

• Provide assurance that the WBL program(s) offered are operated as

intended.

• Ensure that the WBL program and learning becomes part of the

student’s ACP portfolio.

• Are informed of student achievements, placements, employer

evaluations, and other activities.

• Are informed of developments in the WBL programs, including

improved attendance, dropout reduction, increased employability,

and real-world relevance for education.

• Understand program challenges and needs to ensure continuous

improvement of the WBL program.

• Use WBL and other career readiness data to build a more detailed

picture of student and school accomplishments in the district.

In addition, the WBL program selection process should not be limited to

high-ability students only. Rather, WBL is a means of serving all student

populations based on individualized career goals and abilities.

DESIGNATED TEACHER-COORDINATORS

Designated teacher-coordinators ensure that WBL experiences effectively

develop knowledge, skills, attitudes, and work habits that help students

move successfully into adulthood. Teacher-coordinators:

• Plan, develop, administer, and evaluate programs.

• Ensure district policy and programs do not inadvertently create

barriers to access and equity by all special populations.

• Coordinate safety training with the employer.

• Connect and monitor related class instruction.

• Coordinate and monitor on-the-job instruction.

• Advise employers and students.

• Handle community and public relations.

EMPLOYERS

Employers that participate in the WBL program are familiar with the

training and educational aspects of the program and work to achieve

training goals. Employers instruct students in the specic tasks needed

to complete the job as well as information about safety and the general

operation of the business. Employers and worksite supervisors:

• Participate in the development of the individual leadership learning

plan and agreement in cooperation with the student and the

supervising teacher.

• Offer a well-rounded variety of learning experiences.

• Provide training that develops skills for short-term tasks and long-

term opportunities, especially in safety considerations at the

worksite.

• Provide supervision through a workplace mentor.

• Assist students in establishing career goals.

• Advise the student on job performance, growth opportunities, and

networking.

• Reinforce the value and relevance of technical and academic skills.

• Provide for the day-to-day safety of the student within the

organizational experience.

• Maintain a physical and ethical environment that is both appropriate

and benecial.

• Adhere to all state and federal child labor laws as applicable.

• Cooperate with the teacher-coordinators to evaluate the student.

• Communicate regularly with the teacher-coordinators about what is

needed to make the worksite an effective learning environment.

SCHOOL COUNSELORS AND ADVISORS

School counselors and advisors are informed about student career and

social-emotional development as part of the district’s ACP service delivery

system. Their active involvement in the operation of the WBL program

reduces concerns they may have that enrolling students in WBL could

restrict opportunities to enroll in other courses. To demonstrate the

student benets of WBL, counselors and advisors should:

• Participate on employer and related classroom instruction visits.

• Participate in the student admission process.

“If the experience

helps a student make a

career decision toward

that career or away

from that career, both

are a winning situa-

tion in helping that

student make a strong

career match. When

these experiences are

in [high school], they

may help save a family

time and money in the

career search process

down the road.”

—Mary Wussow, Green

Bay Area Public Schools

$

$

15

• Help students determine career interests and aptitudes.

• Provide connections to the student’s ACP and goals.

STUDENTS

• Attend school on a regular basis.

• Notify the teacher-coordinator and the employer in advance when

absence is unavoidable.

• Are fully engaged in learning at school and at the worksite.

• Meet WBL program expectations and requirements such as remaining

in good academic standing.

• Discuss any problems as they arise with the teacher-coordinator.

• Communicate with the teacher-coordinator and the worksite

supervisor to ensure that a safe, effective work/learning environment

is maintained.

• Show initiative at the worksite.

• Accomplish all required training elements outlined in the training plan.

• Complete all necessary WBL documents and reports.

PARENTS AND FAMILY MEMBERS

According to Ohio’s Career Connections, “Parents and family members have

the greatest inuence on a child’s career decisions.” To reach all students,

parents must recognize the value of a WBL program to their children and

be willing to encourage participation. Additional parental support of the

program can take many forms. Encourage parents to:

• Share specic work-related incidents from a positive perspective

• Candidly discuss work challenges and perspectives

• Encourage their student’s reection about the work experience

• Stay informed about school-sponsored opportunities

• Encourage their student’s future goal-setting based on connected

school-work experiences

• Position work as a positive aspect of life

• Ensure student attendance

• Evaluate postsecondary education options

• Endorse the value of WBL experiences to other parents and

community members

• Ensure student transportation needs are met

A small work group of students in

an agriculture class is working on a

simulated problem presented by the

licensed ag teacher: Fish are dying

in a local lake. Water samples are

provided for testing and analysis.

(CTE course).

To turn it into a CBLE:

• Students are expected to go on a eld trip with a local

environmental scientist to obtain water samples and then test

the samples in the eld and in the classroom lab.

• Data is collected, analyzed, and presented to the rest of their

class and a group of citizens concerned about the lake.

To turn it into a WBL:

• Two students from the class assist an environmental company

for a minimum of 90 hours as a local internship. Project tasks,

outlined weekly by the company, support investigation of the

water quality.

• A training agreement with each student has them check in

weekly with the employer to report on tasks related to the water

quality project.

• The students and employer meet in person outside of the ag

class either in the lab, at the lake, or in the classroom during a

designated WBL period.

• Students reect on and are assessed for project progress by the

employer and teacher.

Note all six WBL criteria still need to be met.

CBLE vs WBL?

16

Legal Considerations

Educators, community members, and employers working with minors have

a responsibility to provide youth with the education and experiences that

will prepare them to be college- and career-ready. Fortunately for some,

that includes opportunities to apply work or classroom learning in other

environments. The primary concern, whether minors are learning in school

or out of school, is that students are safe. Employment of minors laws

have developed over time to ensure that youth are not exploited in work

environments and are afforded specic protections.

Guidance has been produced by a team from the Wisconsin Department of

Workforce Development (DWD) and the Wisconsin Department of Public

Instruction (DPI) to assist schools and employers who hire youth. It is the

primary responsibility of the DWD Equal Rights Division to issue permits

and enforce laws that address the employment of minors in the state.

Note that this Guide to Implementing Career-Based Learning Experiences

is meant to be used along with the Guide to Wisconsin’s Employment of

Minors Laws as an interpretive aide and is not meant to replace Wisconsin

Administrative Code Chapter DWD 270 or cover all possible scenarios or

exceptions. Furthermore, this guide does not constitute a legal document

which can be asserted as evidence in a court of law.

Compulsory Attendance

School boards and districts have broad authority and autonomy to

personalize the learning experience for students in the high school grades

to meet the needs of individual students as they progress to graduation.

Published in 2017, Fostering Innovation in Wisconsin Schools also outlines

credit and seat time exibilities to support college and career readiness.

According to Wis. Stat. § 118.33(1)(b), a school board may not grant a high

school diploma to any pupil unless, during the high school grades, the pupil

has been enrolled in a class or has participated in an activity approved by

the school board during each class period of each school day, or the pupil

has been enrolled in an alternative education program, as dened in Wis.

Stat. § 115.28(7)(e). Nothing in this paragraph prohibits a school board from

establishing a program that allows a pupil enrolled in the high school grades

who has demonstrated a high level of maturity and personal responsibility

to leave the school premises for up to one class period each day if the pupil

does not have a class scheduled during that class period.

Each school board submits to DPI high school graduation policies governing

the granting of diplomas (Wis. Stat. § 118.33(1)(f)). Policies include course

requirements, number of clock hours of instruction required to earn one

credit in the courses, and education programs for students with exceptional

educational interests, needs, or requirements.

According to Wis. Admin. Code sec. PI 18.05(1)(d), open campus and

work release may not be approved by a board under this section.

However, a pupil’s employment during school hours may be approved

if the employment is part of or related to the pupil’s instructional

program [school-supervised work-based learning experience sponsored

by an accredited school, the technical college system board, or DWD’s

Youth Apprenticeship program]; or if the employment is approved as an

accommodation for a pupil with exceptional educational interests, needs,

or requirements (Wis. Admin. Code sec. PI 18.04). Note that “work release,”

permitting students to leave the school premises solely for employment is

different from a “work-based learning program,” a program that provides

occupational training and work-based learning experiences. (Wis. Admin.

Code sec. PI 18.05; Wis. Admin. Code sec. PI 18.02(11); Wis. Stat. §

115.363(1)(b))

Districts have the authority to determine the equivalency of learning

experiences outside of the classroom or the modied learning experience

to actual traditional classroom instruction and how those experiences

appear on the transcript (Wis. Stat. § 118.15(1)(c)). Districts should consider

what the implications are for postsecondary plans of the student when

determining how to reect activities or experiences on the transcript.

Districts can structure work-based learning experiences (hours, credit, etc.)

to accommodate the needs of students. Students under 18 cannot work

during school hours unless participating in structured work-based learning

for credit (Wis. Admin. Code sec. DWD 270.10(1)).

Currently, Wis. Stat. 118.56 addresses a specic type of work-based

learning program and requirements for it. This statute does not preclude

any other school-supervised work-based learning experience, such as

DPI’s State-certied Cooperative Education programs, DWD’s Youth

Apprenticeship program (Wis. Stat. § 106.13), or local cooperative

education programs, approved by school boards.

17

Exceptional, Alternative, and Special Education Exceptions

Special education programming in Wisconsin requires students under

individualized education plans (IEPs) to develop annual postsecondary

transition plans (PTPs) beginning at age 14. Furthermore, considerations

for employment during school hours may be allowed if the employment is

approved as an accommodation for a pupil with exceptional educational

interests, needs, or requirements (Wis. Admin. Code sec. PI 18.05(1)(d)).

Under Wisconsin statute, alternative education is dened as an

instructional program, approved by the school board, that utilizes

successful alternative or adaptive school structures and teaching

techniques and that is incorporated into existing, traditional classrooms

or regularly scheduled curricular programs or that is offered in place of

regularly scheduled curricular programs. “Alternative educational program”

does not include a private school, a tribal school, or a home-based private

educational program (Wis. Stat. § 115.28(7)(e)1).

In addition, the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation (DVR) offers

additional support programs to assist individuals with disabilities in

seeking employment as part of transition services. These services include

employment guidance and counseling, assistance nding and keeping a job,

assistive technology, and training. Contact the local DVR ofce for more

information.

Coordinator Licensing

Supervision and coordination of work-based learning (WBL) is a critical

component of quality programs. Several license types can oversee school-

supervised WBL. These are the recommended positions that are uniquely

trained to do this work.

• School-to-Work Coordinator (5011)

• CTE Coordinator (5093)

• Local Vocational Education Coordinator (5193)

Teachers and administrators can oversee this work but are not specically

trained, through an approved program, to implement quality WBL with

delity. WISEStaff reporting can provide specic coding for each of these

positions as part of a district’s data reporting.

Child Labor Laws

CAUTION: This section does NOT cover all of the child labor laws or

exceptions and has been edited for common situations encountered in WBL

programs.

In general, there are two broad categories of youth employment: a regular

youth-employer relationship that exists between a minor and employer

for compensation for productive work for an employer, and a school-

supervised work-based learning experience. Wisconsin Administrative

Code Chapter DWD 270 and the Guide to Wisconsin’s Employment of Minors

Laws address the legal requirements and considerations for all youth

employment.

Employment means that a person is required, or directed by an

employer in consideration of direct or indirect gain or prot, to engage

in any employment, or to go to work, or be at any time in any place of

employment. However, students who are enrolled in school, in a school-

supervised work-based learning experience, sponsored by an accredited

school, the technical college system board, or DWD’s Youth Apprenticeship

program, and receive school credit for program participation, are designated

specically as “student learners.” In order to be considered a student

learner, minors must meet the following criteria:

1. They are enrolled in a school-supervised work-based learning

experience sponsored by an accredited school, the technical college

system board, or DWD’s Youth Apprenticeship Program.

2. They are enrolled in school and receive school credit for program

participation.

3. They receive appropriate safety instruction at the school and at the

workplace.

4. The work performed is under direct and close supervision of a

qualied and experienced person.

5. The work performed in any occupation declared hazardous is

incidental to the training and is for intermittent and short periods of

time.

6. There is a schedule of organized and progressive work processes to

be performed on the job. (Wis. Admin. Code sec. DWD 270.14(3))

18

Furthermore, there are some specic references that should be considered

when operating a school-supervised work-based learning (WBL) program.

Please note that this is not an all-inclusive list of every possible work

circumstance and employers and schools should thoroughly review the

programs and child labor laws at the links above prior to beginning any

school-supervised WBL program.

WORK PERMITS

• Work permits are required for the lawful employment of minors

under 16 years of age in work in connection with the business, trade,

or profession of an employer.

• Work permits are NOT needed for:

– Youth age 16 and older

– Agricultural work

– Domestic employment in a private home that is not a business

– Volunteer work for a nonprot agency

– The Youth Apprenticeship (YA) Program if work is restricted only to

YA skills training

– Work with a nonprot organization in and around the home of an

elderly person or a person with a disability to perform snow shoveling,

lawn mowing, leaf raking, or other similar work usual to the home of

the elderly person or person with a disability (restrictions apply)

– Employment/work under the direct supervision of the parent or

guardian in connection with the parent’s or guardian’s business, trade,

or profession (Wis. Admin. Code sec. DWD 270.05)

AGES OF WORK

• A minor who is 14 years of age or older may not be employed

during the hours that the minor is required to attend school unless

the minor has graduated from high school, passed the general

education development test, or is participating in an approved

school-supervised work-based learning experience for which proper

scholastic credit is given (Wis. Admin. Code sec. DWD 270.10(1)).

• See laws for exceptions to the under 14 years of age law.

HOURS OF WORK

• Minors under 18 are allowed to work during school hours if the

student is enrolled in a school-supervised work-based learning

experience.

• Hours worked as part of a work-experience program during school

hours do not count as part of the total labor law permitted hours of

work per day or per week.

• Wisconsin no longer limits the hours 16- and 17-year-old minors may

work. (Wis. Admin. Code sec. DWD 270.11)

RESTRICTED WORK TASKS

• Student learner status does not override the child labor laws. The

student learner exception limits the minor to performing some

hazardous tasks on an incidental (less than 5 percent of their work

time) and occasional (not a regular part of their job) basis.

• See Guide to Wisconsin’s Employment of Minors Laws for a complete list

of tasks and equipment allowances and restrictions.

Liability and Insurance

In general, if an employer has adequate general liability and workers’

compensation coverage, no additional liability is required as a result of

hiring youth. However, before hiring youth and/or participating in a work-

based learning program, an employer may wish to consult with their

insurance carrier. Ultimately, nal determination of liability in a particular

situation will be determined by a court of law after review of the specic

circumstances.

The party responsible for transportation is liable in case of an accident.

Minors responsible for their own transportation to and from the worksite

are responsible for their own insurance. In instances where the school

provides transportation for student learners, the school may be responsible

for insurance coverage. Only if the employer provides transportation to or

from work for youth may the employer be responsible for this insurance

coverage.

When a minor becomes an employee of a company, they must be covered

by the employer’s workers’ compensation coverage. For agricultural

employers, farmers need to carry workers’ compensation insurance if they

have six or more employees.

Minors can le for unemployment compensation unless the minor is

enrolled full-time in a public educational institution and receives school

credit for participation in a work-based learning program.

19

The employment of minors participating in a school-supervised work-based

learning experience should not impair existing contracts for services or

collective bargaining agreements. Any student learner program that would

be inconsistent with the terms of a collective bargaining agreement should

be approved with the written concurrence of the labor organization and

employer involved. (Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development

2018).

Safety

Ensuring the safety of each student during a work-based learning activity is

required by both the district and the employer. Specic safety instruction

should be incorporated into both classroom and worksite elements of any

career-based and work-based learning experience, including short visits for

tours and job shadows. The following are a few general resources available

to the teacher-coordinator to help address this important topic.

• Youth@Work - United States Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission’s (EEOC). Rights and responsibilities as an employee

to eliminate discrimination in the workplace. Classroom resources

available.

• YouthRules! - United States Department of Labor. National child labor

laws in student friendly webpages and toolkits.

• Safe Work for Young Learners - Youth worker safety information by

hazard from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Student Records

Using student data for district, school, and classroom improvement

planning can be very helpful when used correctly and with the necessary

security and privacy practices in place. Although data can be used to

facilitate change and improvement, the usefulness of this data must be

balanced with the privacy of the students represented by the data. This

includes data about enrollment and participation in WBL programs.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (20 U.S.C. § 1232g;

34 CFR Part 99) and the Wisconsin Pupil Records Law (118.125) protect

the privacy of student education records. The laws apply to all schools

that receive funds under an applicable program of the U.S. Department

of Education. Collection, dissemination, and retention of all student

information should be controlled by local district procedures designed to

implement the primary task of the district while protecting individual rights

and preserving the condential nature of the various types of records.

Furthermore, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and the

Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development provide for limited and

20

secure data access for the State-certied Cooperative Education and Youth

Apprenticeship programs.

Consult the DPI Student Data Privacy resources for more information on

data privacy and responsibilities of school districts.

Wages

Minors must be paid at least minimum wage when engaged in productive

work for an employer. Wisconsin wage statutes require that employers

pay all workers all wages earned on at least a monthly basis, except farm

labor which can be paid at quarterly intervals. Exceptions exist in some

circumstances based on the nature of the work; however, in general,

if a student learner is part of a school-supervised work-based learning

experience, whereby a student trains, and an employer gains advantage

from the work a student completes, then an employer-employee

relationship exists and that student is owed wage compensation. In

addition, the on-the-job training period is regarded as employment time for

minors no matter the length of training time.

Exceptions to paying student wages can fall into the following three

categories. However, caution should be exercised and considerations given

where a student learner may be owed wages.

Student work-like activities: No compensation is required if:

• The primary purpose is educational and the activity is primarily for

the benet of the student.

• The student performs the activities for time periods of one hour or

less per day.

• The student is supervised by an adult.

• Work-like activities may include helping in the school lunchroom or

cafeteria, cleaning a classroom, acting as a hall monitor, performing

minor clerical work in the school ofce or library, or performing tasks

as an extension of the classroom learning experience, e.g., building

sheds for the community.

Volunteer/service learning: Volunteer service is given freely without

consideration or anticipated monetary payment.

• The work is performed for charitable, nonprot organizations,

including nonprot hospitals or nursing homes and government

agencies.

• Commercial businesses may not legally use minors as unpaid

volunteers.

• Minors cannot volunteer for a for-prot business, but they can go

there and shadow or observe as part of an educational experience.

• Written consent of the minor’s parent and supervision by a

responsible adult is required.

• No minor may volunteer in an occupation or place of employment

deemed dangerous.

Intern/trainee: Training is academically oriented for the benet of the

student, and no employer-employee relationship exists. If all six criteria

listed below apply, the trainee or student is not employed:

• The training, even though it includes actual operation of the

facilities of the employer, is similar to that which would be given in a

vocational school;

• The training is for the benet of the trainees or students;

• The trainees or students do not displace regular employees, but work

under their close observation;

• The employer that provides the training derives no immediate

advantage from the activities of the trainees or students, and on

occasion the employer’s operations may actually be impeded;

• The trainees or students are not entitled to a job at the completion of

the training period; and

• The employer and the trainees or students understand that the

trainees or students are not entitled to wages for the time spent in

training.

Otherwise, the trainee or student will be regarded as an employee and must

be paid.

21

Equity and Access

Equitable access to occupational career areas has been a challenge

historically from an age, gender, cultural, and racial perspective. Therefore, it

is more important than ever that each student is able to transition into post

high school education and a promising work life.

Because opportunities for access are complicated by urban, suburban, rural,

and ultra-rural economic contexts, it is important that districts embrace

student access and equity, recognizing that school policies for WBL

programs may actually impede access by some students.

“CTE and WBL teacher-coordinators cannot assume that all students

have access to resources such as transportation, parent, and/or

industry support. We need to be mindful of whom WBL is accessible

while removing barriers for others. Consider the following as it relates

to the coordination of WBL: training agreements, training plans, and

trainee evaluations, and criteria used to accept students into WBL.

How might these coordination tools impact student access? Also

think about the micromessages perceived by students through CTE

and WBL communication (pictures, posters, words, advice; and the

things they see, hear, and experience in their community and school

environment)” (Haltinner 2020).

While there is no one-size-ts-all approach to ensure equity and access for

all students, consider how the following potential barriers may inadvertently

be embedded in your district’s current WBL policies and programs:

• Transportation availability (dependability, safety, and costs in

maintenance and fuel for getting to and from the work setting)

• Time and conicting responsibilities (family, education, and

the adolescent/young adult developmental nature, roles, and

responsibilities)

• Support from parents, spouses, partners, and childcare

• Business and industry access and support due to regulations or hiring

practices (company policies and HIPAA regulations)

• Personal return on investment (ROI) in engaging in the part-time

nature of traditional versions of work-based learning

• Access to experiences across all aspects of the business

• Curricula access in support of school-coordinated work-based

learning especially school-based and work-based conceptual and

technical skills

• Micromessages in monoculture communities and their impact on

student permission-giving (peer, parents, mentors, and teachers)

as encouragement to see and pursue opportunities (Haltinner

2020).

The DPI website provides links to resources through its CTE, ACP, and

Pupil Services webpages. At minimum, WBL program enrollment and

completion data, disaggregated by socio-economic status, disability,

gender, and ethnicity should be collected and reviewed annually to

ensure that WBL program access, participation, and completion are

diverse, and employer hiring practices for WBL programs are not

discriminatory.

Furthermore, Wisconsin’s Framework for Equitable Multi-Level Systems

of Supports (MLSS) should be used to review WBL programs. Using

the 11 key components of the Equitable MLSS provides a model that

districts can review to evaluate a school’s equitable access, continuous

improvement, strong universal levels, and continuum of support for

every student, parent/family, and community partner.

Additional access and equity resources include:

• Promoting Excellence for All (PEFA) training and resources

• DPI Civil Rights Compliance Equity and Diversity

• Pupil Nondiscrimination Self-Evaluation

• The National Alliance for Partnerships in Equity (NAPE)

• Wisconsin’s Project SEARCH for students with disabilities (DWD)

• Wisconsin Statewide Parent Educator Initiative (WSPEI)

– Opening Doors to Employment

• Engaging Special Populations in CTE

“Learning is a life-

long endeavor and

happens beyond the

walls of the school.

From an equity

standpoint, WBL, as

an option, is just as

relevant as preparing

students for college.

The symbiotic rela-

tionship between

community, busi-

ness, and schools is

fostered in a positive

light by students

learning and working

in the local commu-

nity.”

–Greg Benz

School District of

Westeld

$

$

22

Implementing Virtual Options

As stated previously, access to CBLE opportunities is complicated by urban,

suburban, rural, and ultra-rural economic contexts (Haltinner 2020). This is

especially acute in rural areas that are affected by signicant geographical

distances or decreased density of willing K12 partner employers.

Consequently, these factors are further amplied by the varying capacity

to offer similar levels of career-based and work-based learning experiences

supported in larger urban or suburban areas and districts.

The additional challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic has further stressed

typical K12 education CBLE offerings. Economically, CBLE opportunities

could become less frequent as employers, especially small businesses,

focus on immediate needs to stay solvent and support current employees.

However, companies that have capacity can now use innovations and

creativity to provide similar experiences to students. Moreover, these

methods might address rural barriers to access.

As regional collaborative groups take shape in each of the nine regional

economic development organizations statewide, school districts can

leverage a common point of K12 education-business partnerships in high-

skill, high-demand occupational areas. This regional approach can also help

alleviate barriers. By taking advantage of a larger partnership, schools can

offer CBLEs they would not be able to offer on their own.

The following pages outline specics

for CBLEs offered by schools in

partnership with employers. Where

possible, this virtual icon identies

an example of how an experience

might be offered or accessed in a

virtual, remote environment.

A student is hired by a local catering company as part

of the student’s ACP plan in culinary arts. The school

offers this co-op work experience and requires the

student to work 120 hours in the next semester.

There is an outline of progressive work skills, and the

student will receive credit for the work. The school

has a process for the student to reect on the work

and make regular connections with the supervising

teacher. Everything is set for the student to start working when the COVID-19

pandemic hits. The company closes as parties and catering orders are cancelled.

(WBL). While the company is working on smaller carry-out orders to stay in busi-

ness, the employer does not want the student to come in. However, there are

options!

To keep it a WBL:

To move to a VIRTUAL Local Co-Op:

• The employer and student modify work, which was previously planned at the

worksite, to online trainings via video.

• The student tasks are re-assigned to include research or projects the employer

never had time to address before, such as developing new menu plans or inves-

tigating portion sizes and costs based on changing supplier costs.

• The employer regularly checks in with the student and school to ensure learn-

ing and training are on track.

To move to a simulation:

• Sadly, the catering employer lays off the student; however, the supervising

teacher knows of a retired chef that can support the student virtually.

• The student and the former chef connect weekly online and come up with a

new progressive plan for learning tasks as if the student owns a restaurant.

• The student works at home to develop plans, learns skills through industry

videos, and practices and responds to simulated scenarios from the chef as if

operating a restaurant out of the home kitchen.

• Meal planning, practicing cooking skills in the home kitchen, and business-

based scenarios allow the student to have an employer-connected simulated

worksite experience

.

Note all six WBL criteria still need to be met.

CBLE vs WBL?

23

1. Classroom Speaker

2. Company Tour

3. Career Fair

4. Career related

project

5. Part-time or

summer job

6. Job Shadow

7. Career-related

volunteer or service

learning

8.

Career and technical

student organization

(CTSO) or Career-related

out-of-school activity

9. Informational

Interview

10. Career Mentoring

11. Simulated worksite

12. School-based

Enterprise (SBE)

13. Student

entrepreneurial

experience (SEE)

14. Supervised

Agricultural Experience

(SAE)

15. Internship or Local

co-op

16. State-certied

employability skills co-op

17. State-certied

Occupational Program

Co-op Program

18. State-certied Youth

Apprenticeship

Types of Career-Based

Learning Experiences

24

Resources

• For employer career speakers: Inspire Wisconsin Toolkit - Guest

Speaking

• For all: JFF Possible Futures Curriculum

State Webpage

None

Virtual Option

• Arrange for speakers to present via a video-conferencing platform.

CBLE (Know)

1. Classroom Speaker

Denition

An employer visits a classroom to talk with students about a job, business or