Application: 22-02-

(U 39 M)

Exhibit No.:

Date: February 15, 2022

Witness(es): Various

PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY

ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024 BUSINESS-PORTFOLIO PLAN

PG&E ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024-2031 STRATEGIC BUSINESS PLAN

PREPARED TESTIMONY

EXHIBIT 1

-i-

PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY

ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024 BUSINESS-PORTFOLIO PLAN

PREPARED TESTIMONY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter

Title

Witness

Exhibit 1

PG&E ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024-2031

STRATEGIC BUSINESS PLAN

1

PG&E'S VISION FOR ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN

CALIFORNIA: 2024-2031

David Poster

2

ANNUAL PORTFOLIO BUDGETS FOR 2024-2031

Michael D. Burger

3

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR NEW OR MODIFIED

ENERGY EFFICIENCY POLICY

Caroline Massad

Francis

Attachment A

SUMMARY LIST OF POLICY CHANGES

Caroline Massad

Francis

Appendix A

STATEMENTS OF QUALIFICATIONS

Robert W. Bohn

Ben Brown

Michael D. Burger

Caroline Massad

Francis

Rebecca Madsen

David Poster

Exhibit 2

PG&E ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024-2027

PORTFOLIO PLAN

1

PORTFOLIO SUMMARY

David Poster

2

FORECAST METHODOLOGY

Robert W. Bohn

Attachment A

PG&E ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024-2027

PROGRAM-LEVEL ANNUAL COST VARIANCE

EXPLANATIONS

Robert W. Bohn

3

SEGMENTATION STRATEGY

Ben Brown

Attachment A

PROGRAM LEVEL AND SEGMENT LEVEL

METRICS AND TARGETS

Ben Brown

4

SECTOR STRATEGY

Michael D. Burger

Attachment A

RESIDENTIAL PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY

ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024 BUSINESS-PORTFOLIO PLAN

PREPARED TESTIMONY

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(CONTINUED)

-ii-

Chapter

Title

Witness

Attachment B

COMMERCIAL PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

Attachment C

PUBLIC PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

Attachment D

AGRICULTURAL PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

Attachment E

INDUSTRIAL PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

Attachment F

CODES AND STANDARDS PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

Attachment G

NEW CONSTRUCTION PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

Attachment H

LOCAL GOVERNMENT PARTNERSHIPS

PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

Attachment I

WORKFORCE EDUCATION AND TRAINING

PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

Attachment J

FINANCE PROGRAM CARDS

Michael D. Burger

5

PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT

Michael D. Burger

6

EVALUATION, MEASUREMENT AND

VERIFICATION

Caroline Massad

Francis

7

COST AND COST RECOVERY

Rebecca Madsen

Appendix A

PG&E ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024-2027 CEDARS

FILING SUBMISSION LINKS AND RECEIPTS

Exhibit 3

PG&E'S RESPONSES, PURSUANT TO ENERGY

DIVISION TEMPLATE

1

PG&E'S ENERGY EFFICIENCY 2024-2031

APPLICATION TABLES, PURSUANT TO ENERGY

DIVISION TEMPLATE

Michael D. Burger

(PG&E-1)

PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY

CHAPTER 1

PG&E’S VISION FOR

ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN CALIFORNIA: 2024-2031

(PG&E-1)

1-i

PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY

CHAPTER 1

PG&E’S VISION FOR

ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN CALIFORNIA: 2024-2031

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A. Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1-1

1. PG&E’s Core Values .................................................................................. 1-1

2. PG&E’s Vision for EE in California ............................................................. 1-2

3. Background and Purpose of Application .................................................... 1-4

a. Summary of Request ........................................................................... 1-6

b. Support for Request ............................................................................ 1-7

c. Organization of the Remainder of This Chapter .................................. 1-7

B. Description of PG&E’s Service Territory ........................................................... 1-8

C. Principles of PG&E’s EE Portfolio .................................................................. 1-11

1. We Deliver Excellent Customer Experiences ........................................... 1-11

2. We Are Leaders in Environmental Stewardship ....................................... 1-11

3. We Are Here to Serve Our Hometowns ................................................... 1-12

D. PG&E’s EE Portfolio Goals and Desired Outcomes ....................................... 1-13

1. Portfolio Goal: Optimize Delivery of TSB ................................................ 1-15

2. Portfolio Goal: Support Economy-Wide Carbon Neutrality By 2045 ........ 1-15

3. Portfolio Goal: Shape Energy Demand to Match Supply ......................... 1-17

4. Portfolio Goal: Support Customer Resiliency .......................................... 1-19

E. PG&E’s EE Strategies for 2024-2031 ............................................................. 1-20

1. Portfolio Strategies ................................................................................... 1-20

a. Strategy #1: Deliver TSB By Meeting Customers Where

They Are ............................................................................................ 1-21

1) Offer a Diverse EE Portfolio ........................................................ 1-21

2) Design a Portfolio to Meet Customers Where They Are .............. 1-22

(PG&E-1)

PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY

CHAPTER 1

PG&E’S VISION FOR

ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN CALIFORNIA: 2024-2031

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(CONTINUED)

1-ii

3) Enhanced Digital Strategy and Personalized Customer

Journeys ...................................................................................... 1-23

b. Strategy #2: Pursue a Multi-Pronged Approach to Building

Decarbonization ................................................................................. 1-23

1) Support Electrification in Existing and New Buildings ................. 1-23

2) Technical Support and Advocacy Through C&S ......................... 1-28

3) Decarbonize through Equipment Support ................................... 1-28

c. Strategy #3: Deploy Technologies That Are Grid-Responsive and

Demand Flexible ................................................................................ 1-30

1) Align the EE Portfolio With PG&E’s Enterprise-Wide

Coordinated Supply and Load Strategy ...................................... 1-30

2) Utilize the Meter-Based Platform Throughout our Portfolio ......... 1-31

d. Strategy #4: Contribute to Cost Saving Resiliency Solutions for

Customers ......................................................................................... 1-32

1) Use EE to Reduce Customer Costs for Resiliency Solutions ...... 1-33

2) Use EE to Support Individual Customer Resiliency Solutions ..... 1-33

e. Strategy #5: Properly Value the Benefits of EE ................................ 1-33

2. Portfolio Management Strategies ............................................................. 1-34

a. Segmentation Strategy Summary ...................................................... 1-34

b. Sector Strategy .................................................................................. 1-35

c. Budget Distribution Strategy .............................................................. 1-36

d. Outsourcing ....................................................................................... 1-36

1) Strategy to Maintain Outsourcing Target ..................................... 1-36

2) Solicitation Strategies .................................................................. 1-37

e. Portfolio Coordination ........................................................................ 1-38

(PG&E-1)

PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY

CHAPTER 1

PG&E’S VISION FOR

ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN CALIFORNIA: 2024-2031

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(CONTINUED)

1-iii

3. Evaluation, Measurement and Verification ............................................... 1-39

4. Alignment of Business Plan Strategies and Outcomes With

Legislative and CPUC Requirements ....................................................... 1-39

a. Portfolio Design and Budget Alignment With Relevant Action

Plans Beyond the EE Proceeding ...................................................... 1-40

(PG&E-1)

1-1

PACIFIC GAS AND ELECTRIC COMPANY 1

CHAPTER 1 2

PG&E’S VISION FOR 3

ENERGY EFFICIENCY IN CALIFORNIA: 2024-2031 4

A. Introduction 5

In compliance with Decision (D.) 21-05-031, Pacific Gas and Electric 6

Company (PG&E) files this Energy Efficiency (EE) Application requesting an 7

authorized budget cap for its eight-year strategic business plan covering 8

program years 2024-2031, and a four-year revenue requirement request for a 9

program portfolio plan covering 2024-2027.

1

PG&E’s testimony generally aligns 10

with and responds to the prompts in the template created by the Energy Division 11

(Energy Division template), pursuant to D.21-05-031.

2

12

This Exhibit presents PG&E’s strategic business plan and annual budgets 13

for its EE portfolio for 2024-2031. This Exhibit also provides PG&E’s 14

recommendations for new or modified EE policy. 15

With PG&E’s eight-year strategic business plan as the foundation, Exhibit 2 16

presents PG&E’s four-year portfolio plan (2024-2027). 17

1. PG&E’s Core Values 18

PG&E is honored to serve nearly 16 million people across northern and 19

central California with some of the nation’s cleanest energy.

3

At PG&E, we 20

believe customer service is at the core of everything we do, and we are 21

guided by our core purpose of delivering for our hometowns, serving our 22

planet, and leading with love. PG&E’s responsibility as an energy provider 23

to our customers goes beyond our core mission of providing safe, reliable, 24

affordable, and clean energy. We believe that we have a responsibility to 25

build a better future for everyone whose lives we touch. We will measure 26

1

Assessment of Energy Efficiency Potential and Goals and Modification of Portfolio

Approval and Oversight Process, D.21-05-031, Ordering Paragraph (OP) 5, p. 81.

2

D.21-05-031, OP 6, p. 82. While PG&E generally aligns with the Energy Division

template, where necessary, PG&E includes additional information and/or integrates

similar sections . See October 20, 2021 Email from Energy Division “R.13-11-005

Energy Efficiency 2024-2031 Business Plan Templates”.

3

Information from: https://www.pgecorp.com/corp_responsibility/reports/2021/pf01_pge_

overview.html.

(PG&E-1)

1-2

our progress along three areas – focusing on how our programs impact the 1

people we serve, the planet we inhabit, and California’s prosperity. All these 2

changes are done with one focus in mind: to better serve our customers. 3

PG&E’s EE portfolio is an integral piece of protecting the environment 4

and creating a better energy future for our customers. We believe clean 5

energy should be affordable for and inclusive of all economic backgrounds. 6

Our wide range of EE programs help customers reduce their energy use and 7

save money. PG&E’s EE Application details the next generation of our EE 8

portfolio, which is positioned to deliver on these privileges. 9

2. PG&E’s Vision for EE in California 10

PG&E's vision is for EE to help keep customer energy bills affordable, 11

reduce energy demand on the grid, build customer resiliency to climate 12

change, and advance building decarbonization in California. EE is integral 13

to energy sustainability, which is why PG&E has worked for more than four 14

decades to support customer efforts to reduce energy usage. At PG&E we 15

are reaching for new heights pursuing California’s clean energy goals while 16

balancing affordability and equity. 17

EE is a key component of a much broader clean energy and building 18

decarbonization strategy for California.

4

California has passed significant 19

legislation in the pursuit of carbon neutrality,

5

including Senate Bill (SB) 100 20

(2018),

6

which requires renewable energy and zero-carbon resources to 21

supply 100 percent of total electric retail sales in California by 2045,

7

and 22

Executive Order B-55-18 calling for economy-wide carbon neutrality by 23

2045.

8

The California Energy Commission’s (CEC) 2019 EE Action Plan 24

4

Other key components include resources such as distributed solar generation and

energy storage.

5

“Carbon neutrality means that all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions emitted into the

atmosphere are balanced in equal measure by GHGs that are removed from the

atmosphere, either through carbon sinks or carbon capture and storage.” From

Achieving Carbon Neutrality in California, Energy and Environmental Economics, Inc.

(E3), p. 1.

6

https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB100.

7

Ibid.

8

https://www.ca.gov/archive/gov39/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/9.10.18-Executive-Or

der.pdf.

(PG&E-1)

1-3

affirmed that, “energy efficiency is a key piece of California’s efforts to 1

lessen the impacts of climate change.”

9

PG&E’s 2024-2031 EE strategic 2

business plan supports the goals of zero-carbon electricity and 3

economy-wide carbon neutrality, and will work as part of the solution to 4

combat climate change through EE and building decarbonization. Exhibit 2 5

presents how PG&E plans to make progress towards overcoming these 6

challenges in 2024-2027. 7

PG&E’s EE strategic business plan for 2024-2031 is built on portfolio 8

principles, goals, and strategies that enable us to deliver on both our 9

commitments and our vision. PG&E’s three portfolio principles lay the 10

foundation for our portfolio’s goals and strategies. These principles 11

represent our portfolio’s core values that are present in all portfolio activities. 12

PG&E pursues four portfolio goals to achieve key milestones by the end of 13

2027 and 2031. These goals and their associated outcomes are 14

implemented through our portfolio’s strategies. PG&E’s five portfolio 15

strategies guide the broad implementation direction of our portfolio’s 16

activities. These strategies are key for guiding both where and how to direct 17

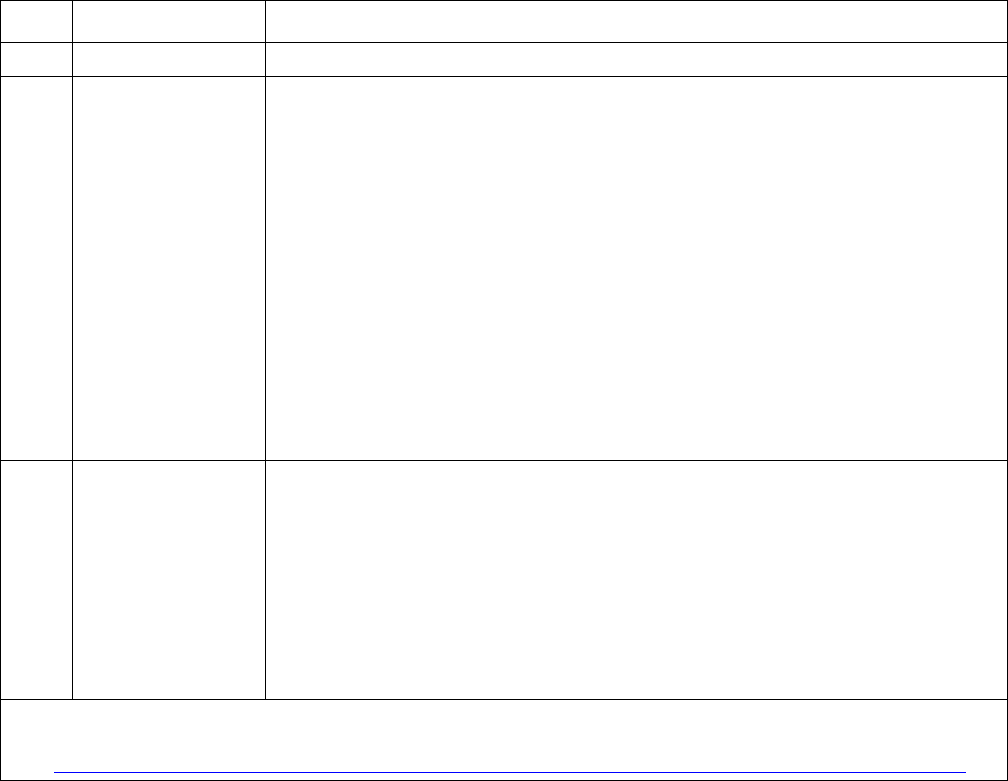

our portfolio’s funding. See Figure 1-1 for the overview of PG&E’s portfolio 18

principles, goals, and strategies. 19

9

CEC, 2019 California Energy Efficiency Action Plan, December 2019, p. 1.

(PG&E-1)

1-4

FIGURE 1-1

SUMMARY OF PG&E’S EE PORTFOLIO GUIDING PRINCIPLES, GOALS, AND STRATEGIES

3. Background and Purpose of Application 1

In May 2021, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC or 2

Commission) issued D.21-05-031 that adopted three major changes in EE 3

policy: (1) a new goals metric, Total System Benefit (TSB); (2) an approach 4

to “segmenting” EE portfolios by program purpose; and (3) a modified 5

portfolio process that requires each EE portfolio administrator (PA)

10

to file 6

an application every four years that includes a four-year detailed program 7

portfolio plan and an eight-year strategic business plan.

11

8

Moving to TSB as the new goals metric and segmenting EE portfolios by 9

program purpose can enable PAs to provide greater value to customers, 10

help achieve California’s long term climate goals and policy objectives, 11

better support equity communities, and focus EE programs on the full range 12

of benefits they can provide to the electric and gas systems. PG&E 13

10

PG&E uses the term “portfolio administrator”, rather than “program administrator”, to

refer to those administering portfolios of EE programs primarily implemented by third

parties.

11

Assessment of Energy Efficiency Potential and Goals and Modification of Portfolio

Approval and Oversight Process, D.21-05-031, pp. 2-3.

(PG&E-1)

1-5

leverages this framework to deliver on the broad portfolio goals outlined in 1

this eight-year strategic business plan. 2

TSB, defined as “the sum of the benefit that a measure provides to the 3

electric and natural gas systems,”

12

replaces energy savings and peak 4

demand goals beginning in 2024.

13

TSB expresses, in Net Present Value 5

dollars, the lifecycle energy, ancillary services, generation capacity, 6

transmission and distribution capacity, and greenhouse gas (GHG) benefits 7

of EE activities, on an annual basis.

14

TSB ties EE goals directly to the 8

avoided cost value of EE savings, capturing the benefits of saving energy 9

during high value hours of the day and year. It is also fuel agnostic and can 10

facilitate the pursuit of building electrification through fuel substitution. In 11

this application, PG&E explains how it will optimize its portfolio to deliver 12

TSB for California. 13

The second policy change directs PAs to assign programs in their EE 14

portfolios to categories, or “segments,” based on their primary purpose.

15

15

There are three segments: resource acquisition (RA), equity, and market 16

support (MS). Codes and Standards (C&S) programs are considered a 17

separate category. Cost-effectiveness requirements apply to the RA 18

segment

16

while the equity and MS segments must adhere to a budget 19

cap.

17

Because cost-effectiveness requirements apply only to the RA 20

12

D.21-09-037, Conclusions of Law (COL) 5, p. 28

13

D.21-05-031, OP 4, p. 81.

14

CPUC TSB Technical Guidance, Version 1.2, October 25, 2021, p. 1. See also p. 7:

“The ACC produces hourly avoided cost values, and the ACC output table for electric

avoided costs instructs the CET whether to use input kW or kWh values, depending

on when the energy is saved. The avoided cost rate is based on price forecasts,

measure impact profiles, climate zones, program administrator, etc. Benefits

associated with avoided kW are only accrued in peak hours, and these benefits flow

into the measure benefits calculation outputted by the CET.”

15

D.21-05-031, OP 2, p. 81.

16

D.21-05-031, OP 3, p. 81 states,

“Beginning in program year 2022, energy efficiency program administrators who are

investor-owned utilities or community choice aggregators shall ensure that the

forecasted benefits exceed the costs of the resource acquisition segments of their

portfolios, as measured by the Total Resource Cost test, without considering Codes

and Standards programs.”

17

D.21-05-031, OP 3-4, p. 81 and p. 16.

(PG&E-1)

1-6

segment, segmentation addresses the increased pressures IOUs 1

experience trying to maintain cost-effective EE portfolios “while also 2

delivering a balanced portfolio that meets all of the Commission’s numerous 3

policy objectives.”

18

PG&E continues to balance cost-effective program 4

delivery with critical policy objectives through equity and MS programs. 5

PG&E presents an EE portfolio with a RA segment that is overall forecasted 6

to achieve a cumulative Total Resource Cost (TRC) ratio greater than 1.0 for 7

each of the four-year portfolio cycles. PG&E has balanced its RA segment 8

in line with the CPUC’s expectations

19

and through the portfolio 9

management strategies discussed in section E.2 below and Exhibit 2, 10

Chapter 5, PG&E will continue to focus on cost-effective program delivery 11

through effective program performance management. See Exhibit 2, 12

Chapter 3 for PG&E’s portfolio segmentation strategy. 13

This eight-year strategic business plan provides high-level descriptions 14

of the following six areas requested by the Energy Division:

20

(1) a 15

description of PG&E’s service territory; (2) the desired outcomes for PG&E’s 16

EE portfolio; (3) major portfolio strategies to achieve the desired outcomes; 17

(4) portfolio management strategies such as portfolio segmentation, sector 18

strategies, budget distribution, outsourcing, and portfolio coordination; 19

(5) evaluation, measurement and verification (EM&V) strategies; and 20

(6) alignment with legislative and CPUC requirements and relevant action 21

plans. 22

a. Summary of Request 23

PG&E requests that the Commission approve its eight-year 24

authorized budget cap request for 2024-2031 of approximately 25

$2.8 billion, which includes two four-year portfolio cycles. The 26

18

D.21-05-031, p. 10.

19

D.21-05-031, at p. 22 in discussion regarding TRC ratio requirement of 1.0 or greater:

“This does not mean that each individual resource acquisition program must be

cost-effective on its own. Program administrators may balance their resource

acquisition programs within the resource acquisition segment of their portfolios to

ensure that the segment overall meets the 1.0 criteria.”

20

EE Business Plan and Application Template – Final from ED with EMV, received via

Energy Efficiency Proceeding Service List Rulemaking (R.) 13-11-005 on October 20,

2021.

(PG&E-1)

1-7

authorized budget cap includes approximately $566 million requested on 1

behalf of Regional Energy Networks (RENs) and Community Choice 2

Aggregators (CCAs) within PG&E’s territory.

21

3

The first four-year portfolio cycle covers 2024-2027 and includes a 4

revenue requirement of approximately $1.4 billion inclusive of 5

approximately $272.7 million requested on behalf of RENs and CCAs 6

within PG&E’s territory. See Chapter 2 for detail regarding the 7

eight-year authorized budget cap request. See Exhibit 2, Chapter 2 for 8

the 2024-2027 forecast methodology. 9

b. Support for Request 10

PG&E’s request for 2024-2031 enables PG&E to achieve 11

cumulative TSB of approximately $1.9 billion and a TRC ratio

22

for its 12

RA portfolio of 1.16. It also enables PG&E to support legislative and 13

climate priorities for California such as doubling EE and reducing GHG 14

emissions and executing on the portfolio strategies further described 15

below. Section E.4 below provides more information on the alignment of 16

PG&E’s strategic business plan with legislative and CPUC requirements 17

and relevant action plans. 18

c. Organization of the Remainder of This Chapter 19

• Section B – Description of PG&E’s Service Territory; 20

• Section C – Principles of PG&E’s EE Portfolio; 21

• Section D – PG&E’s EE Portfolio Goals and Desired Outcomes; and 22

• Section E – PG&E’s EE Portfolio Strategies for 2024-2031. 23

21

This request reflects the budget needs for 2024-2031 of RENs and CCAs approved for

PA status as of January 14, 2022. This includes Bay Area Regional Energy Network

(BayREN), CleanPowerSF, Marin Clean Energy (MCE), San Jose Clean Energy (SJCE)

and Tri-County Regional Energy Network (3C-REN). Should REN or CCA filing

budgets differ from what is provided, or should REN or CCA PA statuses change,

PG&E’s authorized budget cap request will need to be amended. PG&E’s may need to

submit supplemental or revised testimony. See Chapter 3 for PG&E’s proposal to

account for changes in REN and/or CCA PA status.

22

California Standard Practice Manual discusses TRC beginning on p. 18.

https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/-/media/cpuc-website/files/uploadedfiles/cpuc_public_website/

content/utilities_and_industries/energy_-_electricity_and_natural_gas/cpuc-standard-pr

actice-manual.pdf.

(PG&E-1)

1-8

B. Description of PG&E’s Service Territory 1

PG&E delivers some of the nation’s cleanest energy

23

to approximately 2

16 million people throughout a 70,000-square-mile service area in northern and 3

central California. There are approximately 5.5 million electric customer 4

accounts and 4.5 million natural gas customer accounts.

24

In 2021, PG&E 5

established a Regional Service Model that has five regions: 6

1) North Coast; 7

2) North Valley/Sierra; 8

3) Bay Area; 9

4) South Bay/Central Coast; and 10

5) Central Valley. 11

PG&E’s EE portfolio intends to work within these five regions to address 12

customer and community specific needs. See Figure 1-2 for PG&E’s 13

regionalization map. 14

23

About 85 percent of the electricity delivered is GHG-free. PG&E 2021 Corporate

Sustainability Report.

24

PG&E Corporate Sustainability Report, as of December 31, 2020, 4.8 million residential

and 0.7 million commercial, industrial, and other electric distribution accounts;

4.3 million residential and 0.2 million commercial and industrial natural gas distribution

accounts.

(PG&E-1)

1-9

FIGURE 1-2

PG&E REGIONALIZATION MAP

PG&E provides brief discussions on certain areas of diversity within our 1

territory that provide opportunities and challenges for the proposed EE portfolio. 2

Diversity in Income and Economic Resources 3

At PG&E, we believe clean energy should be affordable for and accessible 4

to customers of all economic backgrounds, but recognize that within PG&E’s 5

service territory, there are certain geographic areas in which customers may 6

face greater burdens to affording essential utility services. An analysis in the 7

CPUC’s 2019 Annual Affordability Report finds that these geographic areas are 8

“where utility services are currently least affordable for low-income households 9

(PG&E-1)

1-10

(as measured by AR

20

)

25

and where residents are most vulnerable to future 1

increases in essential service (as measured by SEVI).”

26

PG&E’s EE portfolio 2

provides broad opportunities to help customers reduce their energy use and 3

save money by making essential services more affordable. Pursuant to 4

D.21-05-031, PG&E’s EE portfolio includes funding for equity segment programs 5

that provide EE to hard-to-reach or underserved customers and disadvantaged 6

communities (DAC) to advance the Commission’s Environmental and Social 7

Justice (ESJ) Action Plan draft 2.0.

27

See Exhibit 2, Chapter 3, Section E for 8

the equity segment strategy. One example of an equity segment program is the 9

new Residential Equity Placeholder program that targets low to 10

moderate-income customers with certain EE and retrofit electrification solutions. 11

See Exhibit 2, Chapter 4, D.1. 12

Diversity of Geography and Terrain 13

More than half of PG&E’s service territory lies in the High Fire Threat 14

Districts (HFTD) Tiers 2 and 3 as identified by the CPUC in 2018.

28

15

Approximately 10 percent of PG&E’s electric customers

29

reside in HFTD areas. 16

PG&E’s EE portfolio can play a role to support energy resiliency particularly for 17

customers in HFTD.

30

18

25

An abbreviation for the Affordability Ratio (AR) for household in the 20th percentile of

the income distribution

26

2019 Annual Affordability Report, April 2021, CPUC, p. 10. For more information, see

the following link:

https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/-/media/cpuc-website/industries-and-topics/reports/2019-annu

al-affordability-report.pdf. Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index (SEVI): Describes the

relative socioeconomic characteristics of communities – in terms of poverty,

unemployment, educational attainment, linguistic isolation, and percent of income spent

on housing – to quantify how the same utility cost may affect one community’s ability to

pay more than another’s.

27

D.21-05-031, p. 81, OPs 2 and 4. See also ESJ Action Plan, Draft 2.0, available at:

https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/esjactionplan/.

28

Available at: https://cpuc_firemap2.sig-gis.com/ (last accessed Feb. 9, 2022). Tier 2

consists of areas on the CPUC Fire Threat Map where there is an elevated risk for

wildfires. Tier 3 consists of areas on the CPUC Fire Threat Map where there is an

extreme risk for wildfires.

29

With a “customer” defined as an electric meter or service point, each of which generally

represents at least one household or business.

30

“Energy resiliency” in this context refers to ensuring that homes, businesses, and

facilities have reliable energy.

(PG&E-1)

1-11

C. Principles of PG&E’s EE Portfolio 1

This section details the underlying principles of PG&E’s EE portfolio for the 2

years covered in this strategic business plan from 2024-2031. PG&E’s EE 3

portfolio vision is built on three guiding principles: (1) We Deliver Excellent 4

Customer Experiences; (2) We are Leaders in Environmental Stewardship; and 5

(3) We are Here to Serve our Hometowns. 6

1. We Deliver Excellent Customer Experiences 7

PG&E is focused on providing excellent customer experiences to 8

increase the overall participation and engagement in EE. PG&E will strive 9

for a portfolio of EE offerings that: 10

• Are easy to participate in; 11

• Are integrated with other energy management programs; and 12

• Provide for a more personalized and digitized customer experience. 13

Through supporting its customers, PG&E hopes to build energy 14

resiliency to climate change, reduce GHG emissions, lower customer utility 15

costs and improve grid reliability. PG&E’s EE portfolio includes plans to 16

engage customers as energy saving partners and build long-term 17

relationships to drive positive change. 18

2. We Are Leaders in Environmental Stewardship 19

PG&E embraces its role in achieving California’s goal of carbon 20

neutrality and to move to a climate-resilient economy. PG&E’s EE portfolio 21

can address climate change by both delivering solutions that help to 22

decarbonize customer’s homes and buildings and by supporting the use of 23

clean and renewable energy resources powering our electric system.

31

24

Through PG&E’s EE portfolio of energy savings measures, PG&E can 25

help reduce the overall carbon emissions of our customers’ homes and 26

businesses by permanently reducing their energy consumption. The energy 27

savings that PG&E delivers to our customers removes: 28

31

For example, shortly after filing its EE application, PG&E intends to file a separately

funded, but complementary, application for a GHG-optimized building decarbonization

offering (similar to Southern California Edison's (SCE) Clean Energy Optimization Pilot

(CEOP)).

(PG&E-1)

1-12

• Carbon emissions through both avoiding the need to generate electricity 1

through non-renewable means (such as natural gas fueled power 2

plants); and 3

• The end-use combustion of natural gas in our customer homes and 4

businesses. 5

PG&E’s EE portfolio also leverages fuel-substitution energy savings 6

measures where we can retire old, inefficient natural gas equipment. PG&E 7

can provide our customers support for high-efficiency electric equipment in 8

their place. 9

As PG&E’s electricity supply moves towards 100 percent clean and 10

renewable energy by 2045 to meet our Renewable Portfolio Standard goal, 11

we understand that energy supply availability and cost are key 12

considerations when developing and providing customer energy savings 13

products, programs, and services through our EE portfolio. PG&E’s EE 14

portfolio is working closely with other PG&E demand and energy supply 15

teams to ensure that we can offer a comprehensive Demand Side 16

Management (DSM) approach to reducing customer demand and energy 17

use and provide options to support a safe, reliable, affordable, and clean 18

energy supply. 19

3. We Are Here to Serve Our Hometowns 20

PG&E’s EE portfolio will help serve our hometowns by expanding 21

customer access with more equity-based program offerings, supporting 22

customer resiliency, and enabling the workforce of tomorrow through 23

workforce, education, and training. PG&E also believes that EE can support 24

affordability through a thoughtfully procured portfolio of programs that 25

achieve cost-savings for all customers (not only program participants). 26

Part of serving our hometowns is making sure that everyone and 27

everything is safe. Safety is embedded in everything we do. PG&E uses a 28

comprehensive safety plan for ensuring the safety of our customers, 29

contractors, and employees as we conduct energy efficiency program 30

operations. Our processes include identifying risk level rankings (Low, 31

Medium, High) based on pre-existing contractor safety standard criteria. We 32

provide additional oversight and monitoring of our contractors out in the field 33

by performing regular safety observations. In addition, PG&E is sensitive to 34

(PG&E-1)

1-13

customers’ needs during the COVID-19 pandemic and will continue to adjust 1

its programs as needed to safely meet its customers’ needs. 2

D. PG&E’s EE Portfolio Goals and Desired Outcomes 3

PG&E’s EE portfolio goals for 2024-2031 are as follows: (1) optimize 4

delivery of TSB; (2) support California’s goal of economy-wide carbon neutrality 5

by 2045; (3) shape energy demand to match supply, and (4) support customer 6

resiliency. The portfolio strategies and tactics in PG&E’s EE portfolio application 7

are designed to pursue these goals and promote these outcomes. 8

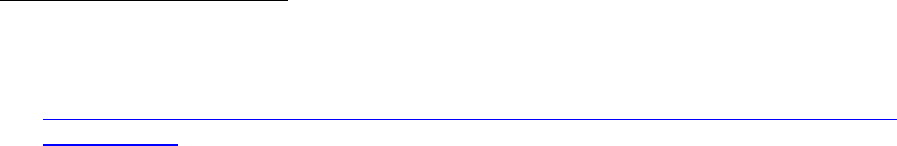

PG&E is pursuing these goals to achieve key milestone desired outcomes 9

throughout this application period outlined in Figure 1-3 below. PG&E provides 10

these aspirational targets by 2027 and by 2031. 11

(PG&E-1)

1-14

FIGURE 1-3

PG&E EE PORTFOLIO DESIRED OUTCOMES

_______________

(a) PG&E’s cumulative TSB goals for 2024-2027 adopted in D.21-09-037, p.19.

(b) PG&E’s cumulative TSB goals for 2024-2031 adopted in D.21-09-037, p.19.

(c) Cumulative lifecycle CO2 emissions from PG&E’s EE Application CET output forecast, converted from

short tons to metric tons, including codes and standards.

(d) PG&E is defining this timeframe as the hours of 4pm to 9pm, every day to align with a frequently used peak

pricing period of PG&E’s electric rate plans. PG&E will measure progress towards this goal in watt-hours

(Wh) as opposed to only DEER defined peak watts.

(e) PG&E is not including a target figure as the savings in watt-hours for only the specific time periods of

concern is not yet an available CET output. PG&E-recommended improvements to CET outputs and overall

EE benefit calculations are discussed in subsequent chapters throughout this application.

(PG&E-1)

1-15

1. Portfolio Goal: Optimize Delivery of TSB 1

As the new adopted metric, one of PG&E’s key considerations in 2

optimizing for TSB focuses on delivering programs and services at multiple 3

interaction points, and deploying a variety of program types, intervention

32

4

approaches, and transaction structures to increase customer participation. 5

This increased participation will help PG&E deliver on its TSB portfolio 6

metric by generating benefits from all customer sectors across our diverse 7

service territory. 8

PG&E plans to measure progress towards achieving this portfolio goal 9

by delivering at least the cumulative TSB goal by the end of each of our two 10

portfolio cycles, by 2027 and by 2031, as required by D.21-09-037.

33

These 11

cumulative figures are provided in Figure 1-3. 12

Additional details on PG&E’s approach to portfolio optimization are 13

included in Exhibit 2, Chapter 5 of this application. 14

2. Portfolio Goal: Support Economy-Wide Carbon Neutrality By 2045 15

PG&E is committed to helping California succeed in reaching its climate 16

commitments of reducing GHG emissions by 40 percent below 1990 levels 17

by 2030,

34

and ultimately reaching economy-wide carbon neutrality by 18

2045.

35

Based on recent reporting from the California Air Resources Board 19

(CARB),

36

“California will require much deeper GHG emissions reductions 20

to reach its [targets]”

37

and “by any measure, in any scenario, achieving 21

32

PG&E uses the term “intervention” to broadly cover the various points at which our

portfolio’s funded activities influence a customer or other market actors’ behavior or

actions, and it is through this influence that we can generate value in the form of

benefits for our customers.

33

D.21-09-037, p. 19.

34

See California SB 32 (2016).

35

See California Executive Order B-55-18 (2018).

36

California Greenhouse Gas Emissions for 2000 to 2019: Trends of Emissions and

Other Indicators, CARB, July 28, 2021, available at:

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/classic/cc/ca_ghg_inventory_trends_2000-201

9.pdf

37

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/news/latest-state-greenhouse-gas-inventory-shows-emissions-c

ontinue-drop-below-2020-target.

(PG&E-1)

1-16

carbon neutrality by 2045 will require a wholesale transformation of 1

California’s energy economy.”

38

2

PG&E recognizes that meeting this challenge and supporting 3

California’s climate commitments requires an EE portfolio focused on 4

innovative and integrated building decarbonization and electrification 5

solutions.

39

To ensure that our EE portfolio is aligned with and contributing 6

to California’s decarbonization goals, PG&E sets a target of 35.4 million 7

metric tons of cumulative lifecycle carbon dioxide (CO

2

) emissions 8

reductions

40

through our EE portfolio by 2031 (see Figure 1-3). GHG 9

emissions reductions is a useful metric to track progress towards the state’s 10

carbon neutrality target by 2045 because it is a common unit of 11

measurement for decarbonization. This GHG reduction target results from 12

PG&E’s embrace of building and end-use electrification, our commitment to 13

helping ensure California has a capable and qualified workforce able to 14

implement these carbon reduction investments, our continued leadership in 15

building codes and appliance standards advocacy, and our support for local 16

jurisdictions and the building community. PG&E’s EE portfolio is also 17

coordinating with other customer energy management portfolios and energy 18

supply teams to deliver comprehensive, renewable energy optimized load 19

management practices to further reduce GHG emissions from our 20

customers’ electricity use and to help meet the needs of a reliable and 21

low-carbon energy system of the future. See Section D.3 regarding this 22

coordination. 23

38

Achieving Carbon Neutrality in California: PATHWAYS Scenarios Developed for the

California Air Resources Board, E3, p. 9.

39

For example, as stated above shortly after filing its EE application, PG&E intends to file

a separately funded, but complementary, application for a GHG-optimized building

decarbonization offering (similar to SCE’s CEOP).

40

PG&E selected this metric because it is available as an output from the CPUC’s

Cost-Effectiveness Tool (CET). The EE portfolio’s contribution toward carbon neutrality

may be understated because lifecycle CO

2

emissions reduction only captures the

emissions reductions associated with interventions in PG&E’s EE portfolio that deliver

energy savings, while additional activities that support GHG emissions reductions, but

do not directly deliver energy savings such as Workforce Education and Training

(WE&T) programs are not captured through this metric. Additionally, GHG emissions

reductions from low-GWP refrigerant measures are not captured in this metric. CO

2

equivalent may be a better metric however this is not available as a CET output.

(PG&E-1)

1-17

Qualitatively, PG&E is proposing two related outcomes by the end of 1

each the two four-year portfolio cycles. During the first portfolio cycle of 2

2024-2027, PG&E plans to increase the rate of electrification above the 3

natural rate of adoption by making electrification simple, easy, convenient, 4

and valued by customers. By the end of the second portfolio cycle in 2031, 5

PG&E anticipates electrification will be a primary focus of its EE portfolio 6

and plans to remove natural gas equipment financial support except where 7

there are no viable alternatives. 8

3. Portfolio Goal: Shape Energy Demand to Match Supply 9

Achieving California’s goal of renewable energy and zero-carbon 10

resources supplying 100 percent of total electric retail sales in California by 11

2045 will require an increase in clean, but variable, renewable generation

41

12

and a reduction (or elimination) of fossil-based, but firm, fast-ramping 13

generation.

42

The CEC Draft Staff Analysis of Potential Amendments to the 14

Load Management Standards notes that “as renewable resources replace 15

conventional fossil-fuel powered plants, the electric grid will place increasing 16

value on resources that can balance supply and demand.”

43

The 2021 17

SB 100 Joint Agency Report describes load flexibility as, “the ability to shift 18

electricity use to other parts of the day,” and describes load flexibility as 19

“critical” to electric reliability and affordability, noting that it can also reduce 20

GHG emissions by shifting electricity use to times when the grid relies on 21

cleaner energy.

44

The need for resources that can balance supply and 22

demand will likely be heightened further as PG&E looks ahead to retiring its 23

2,200 megawatt Diablo Canyon Power Plant in 2025. 24

41

For example, solar photovoltaic generation only generates electricity when the sun is

shining, and wind turbines only generate in correct wind conditions.

42

For example, natural gas power plants would be able to generate electricity whenever

needed, regardless of external conditions.

43

Draft Staff Analysis of Potential Amendments to the Load Management Standards, p. 7.

Available:

https://www.energy.ca.gov/publications/2021/analysis-potential-amendments-load-man

agement-standards.

44

Available here:

https://www.energy.ca.gov/publications/2021/2021-sb-100-joint-agency-report-achieving

-100-percent-clean-electricity.

(PG&E-1)

1-18

Broadly, shaping energy demand to match supply means delivering the 1

right demand-side resources, in the right places, and at the right times, to 2

keep the grid operating and delivering power to customers. In practice, this 3

effort requires coordination of multiple DSM activities, including electric rate 4

design, demand response (DR), distributed generation and energy storage, 5

electric vehicle charging, and EE. 6

PG&E’s EE portfolio can help shape energy demand to match supply by 7

providing: 8

a) EE products and services that permanently reduce load during times of 9

unavailable, high-cost, or non-renewable supply; 10

b) EE products that have flexible demand capabilities (products able to 11

reduce, shift, or shape usage in response to customer or grid needs, or 12

electric retail rates); and 13

c) Integrated demand side management (IDSM) programs able to deliver 14

EE in combination with one or more DSM activities (other DSM activities 15

are mentioned above). 16

PG&E plans to quantitatively measure progress on this goal by tracking 17

the delivered energy savings during anticipated times of electric system 18

constraint. See Figure 1-3 for more information. 19

Qualitatively, PG&E proposes two distinct but related outcomes by the 20

end of each of the two portfolio cycles by 2027 and by 2031. During our first 21

portfolio cycle of 2024-2027, PG&E intends to track customer awareness of, 22

and access to opportunities to manage their energy use to support a clean 23

and reliable electric grid. By the end of the second portfolio period, PG&E 24

intends to leverage our entire DSM portfolio of customer programs, including 25

our EE portfolio, to provide customers a comprehensive and integrated 26

pathway to manage their energy use to support a clean and reliable electric 27

grid. 28

(PG&E-1)

1-19

4. Portfolio Goal: Support Customer Resiliency

45

1

As stated above, more than half of PG&E’s service territory lies in the 2

HFTD, Tiers 2 and 3, as identified by the CPUC in 2018.

46

Customers in 3

these HFTD areas may be more interested in ensuring customer resiliency, 4

and PG&E’s EE portfolio can play a role in supporting these efforts. 5

PG&E’s EE portfolio is committed to supporting statewide GHG 6

reduction and carbon neutrality efforts, and to slow and hopefully reverse 7

the impacts of climate change. However, even with this focus on combating 8

climate change, PG&E recognizes that in the near term for the safety of our 9

customers and communities, PG&E may need to turn off power in certain 10

communities during severe weather events to help prevent wildfires. These 11

Public Safety Power Shutoffs (PSPS) are a necessary tool of last resort to 12

help keep our customers safe from wildfires. 13

EE has long been placed first in the “loading order” of resources 14

potentially available to meet energy needs.

47

Since EE products and 15

services can both reduce customer load as well as provide customers the 16

tools to manage their energy use on an ongoing basis, our EE portfolio can 17

help reduce the amount of generation needed to power customer homes 18

and businesses. 19

We plan to measure our progress in supporting customer resiliency 20

through the breadth of customers and resiliency projects that can leverage 21

45

We use the term customer resiliency to mean the ability for a customer or community to

keep their homes and businesses powered through alternative sources during an

outage event. These alternative power sources may be individual customer owned

generation and energy storage assets, community solutions such as a microgrid using

locally sited power generators which operate during outage events. It can also include

a permanent alternative power solution such as a remote grid or fixed power solution.

46

Available at: https://cpuc_firemap2.sig-gis.com/ (last accessed Feb. 9, 2022). Tier 2

consists of areas on the CPUC Fire Threat Map where there is an elevated risk for

wildfires. Tier 3 consists of areas on the CPUC Fire Threat Map where there is an

extreme risk for wildfires.

47

First adopted in the California Energy Action Plan in 2003, and reaffirmed in State of

California Energy Action Plan II, 2005. “As stated in EAP I and reiterated here, cost

effective energy efficiency is the resource of first choice for meeting California’s energy

needs. Energy efficiency is the least cost, most reliable, and most

environmentally-sensitive resource, and minimizes our contribution to climate change.

California’s energy efficiency programs are the most successful in the nation and we

want to continue to build upon those successes.” p. 3.

(PG&E-1)

1-20

EE to generate overall cost savings for our customers. Additional details 1

regarding the resiliency projects supported by our EE portfolio are discussed 2

below in Section E.1. Our 2024-2027 portfolio offers resiliency support 3

programs that intend to achieve cost savings for resiliency projects designed 4

and implemented in coordination with EE. By the end of our 2031 portfolio, 5

PG&E anticipates expanding this EE support across our portfolio and 6

throughout our service territory so that an even broader scope of resiliency 7

projects may optimally size their electricity generation and other 8

infrastructure assets by first employing all cost saving EE measures. 9

E. PG&E’s EE Strategies for 2024-2031 10

1. Portfolio Strategies 11

This section summarizes the key strategies for PG&E’s EE portfolio for 12

the eight-year strategic business plan period of 2024-2031: (1) deliver TSB 13

by meeting customers where they are; (2) pursue a multi-pronged approach 14

to building decarbonization; (3) deploy technologies that are grid-responsive 15

and demand flexible; (4) contribute to cost-saving resiliency solutions for 16

customers; and (5) properly value the benefits of EE. As these key 17

strategies also form the basis for PG&E’s 2024-2027 portfolio plan, PG&E 18

includes more detail as referenced accordingly. 19

The following strategy prompts in italics requested by the CPUC in the 20

Energy Division template are mapped to the above five PG&E strategies, as 21

noted below in Table 1-1: 22

(PG&E-1)

1-21

TABLE 1-1

STRATEGY PROMPT MAPPING

Line

No.

Strategy Prompts from Energy Division Template

PG&E Portfolio Strategy

That Addresses CPUC

Prompt

1

Strategy for application/use of various and new methods for

savings forecasting and quantification methods

(e.g., normalized metered energy consumption (NMEC)

including requirements in Public Resources Code Section

25310(c)(5)).

Strategy #3

2

Strategies for market intervention and EE adoption:

e.g., targeted points of intervention; delivery

channels/platforms/methods.

Strategies #1-4

3

New strategies for spurring innovation: e.g., cultivating new,

diverse, businesses to enter EE design/implementation,

cultivating relationships with traditional actors in other markets

to enter EE design/implementation, supporting the adoption of

new and evolving GHG reducing technologies.

Strategies #1-4

4

Strategy for incorporating low global warming potential (GWP)

refrigerants in the portfolio

Strategy #2

a. Strategy #1: Deliver TSB By Meeting Customers Where They Are 1

Delivering programs and services structured to address customer 2

concerns and potential barriers to participating in EE programs, and 3

which are offered through multiple interventions

48

and interaction points, 4

can meet customers’ needs and increase participation. Increasing 5

participation is one pathway to delivering on PG&E’s EE portfolio metric 6

of TSB by generating benefits from a wide range of customer sectors 7

across our service territory. PG&E proposes three key tactics below to 8

pursue this strategy: (1) offer a diverse EE portfolio; (2) design a 9

portfolio that meets customers where they are; and (3) enhance digital 10

strategies and personalize customer journeys. 11

1) Offer a Diverse EE Portfolio 12

PG&E will leverage its PA role to develop complementary 13

interventions, programs, and strategies that provide customers 14

opportunities to participate in EE that best suit their needs. PG&E’s 15

48

Interventions are actions taken by the program administrator to influence a customer’s

energy efficiency. This can be in the form of activities including but not limited to:

financial incentives, technical assistance, efficiency C&S, and informational products.

See Exhibit 2, Chapter 4 for details on interventions.

(PG&E-1)

1-22

EE portfolio will employ diverse programs, services, transaction 1

structures (such as financing and performance-based incentives), 2

and intervention channels. Our commitment to offering a varied 3

portfolio will allow PG&E to deliver timely solutions for customers 4

related to: replacing aging infrastructure with new, high-efficiency 5

solutions; helping customers upgrade their facilities without 6

disrupting their operations; creating ongoing energy management 7

partnerships to control operating costs; and offering attractive capital 8

access structures allowing customers to make investments in EE 9

without jeopardizing other needs. See Exhibit 2, Chapter 4, 10

Sections D and E for more detail. 11

2) Design a Portfolio to Meet Customers Where They Are 12

PG&E’s role as a PA is to design a portfolio of programs that 13

meets the needs of its diverse population of customers. PG&E’s 14

customers’ perceptions about EE and energy management are 15

highly varied. See Exhibit 2, Chapter 4, Section A.3 for insights on 16

PG&E’s customer perceptions. PG&E identifies three areas to 17

deliver on its portfolio strategy through customer-centric principles: 18

(1) increasing awareness of EE and energy management 19

opportunities; (2) providing motivation for customers to pursue EE; 20

and (3) removing barriers that could impede customers’ participation 21

in EE. 22

As part of this, marketing is a critical element of the customer 23

experience. This includes broad awareness and education as well 24

as more program specific marketing. This dual approach engages 25

customers through multiple channels, to drive EE program adoption 26

and energy management behavior change. PG&E’s marketing uses 27

a combination of traditional and newer marketing channels to meet 28

customers where they are. Through multi-touch and multi-channel 29

campaigns, customers move through the program adoption journey 30

including awareness, interest, evaluation, and conversion. PG&E 31

intends to continue to use this marketing approach to drive 32

participation in EE programs and deliver on our portfolio goals. See 33

Exhibit 2, Chapter 4, Section A.4 for more detail. 34

(PG&E-1)

1-23

3) Enhanced Digital Strategy and Personalized Customer 1

Journeys 2

PG&E plans to expand online customer access to information 3

and will connect customers to technical experts who can help them 4

create EE and decarbonization action plans. PG&E’s online EE 5

solutions aim to provide personalized recommendations to 6

customers for planning and implementing EE and decarbonization 7

activities. These solutions can provide customers with information 8

regarding their energy bills and energy use, rate plan options, 9

energy management programs including EE and DR, and clean 10

energy solutions for their homes, businesses, and transportation. 11

PG&E anticipates that simplified, tailored customer experiences will 12

lead to increased customer participation across our EE portfolio and 13

other energy management programs. See Exhibit 2, Chapter 4 for 14

more details. 15

b. Strategy #2: Pursue a Multi-Pronged Approach to Building 16

Decarbonization 17

PG&E is committed to supporting building decarbonization while 18

keeping energy affordable by managing an equitable and viable 19

transition to zero-carbon energy alternatives for customers. Within EE 20

programs, PG&E’s support for building decarbonization reflects the 21

different needs of customers and communities with programmatic 22

approaches such as equipment incentive and financing programs, 23

customer education, WE&T, and advocacy to improve appliance 24

standards and building codes. PG&E provides its high-level vision for its 25

building decarbonization strategies through EE below. 26

1) Support Electrification in Existing and New Buildings 27

While PG&E’s approach to building electrification differs for 28

existing and new buildings, the desired outcome for both is for 29

all-electric or electric-ready buildings. 30

a) Existing Building Electrification 31

Decarbonizing California’s existing building stock must be 32

done thoughtfully as it has the potential to exacerbate issues of 33

(PG&E-1)

1-24

affordability and equity for remaining gas customers. As E3 1

highlights in its report The Challenge of Retail Gas in 2

California’s Low-Carbon Future, “unsustainable increases in gas 3

rates and customer energy bills could be seen after 2030, 4

negatively affecting customers who are least able to switch 5

away from gas, including renters and low-income residents.”

49

6

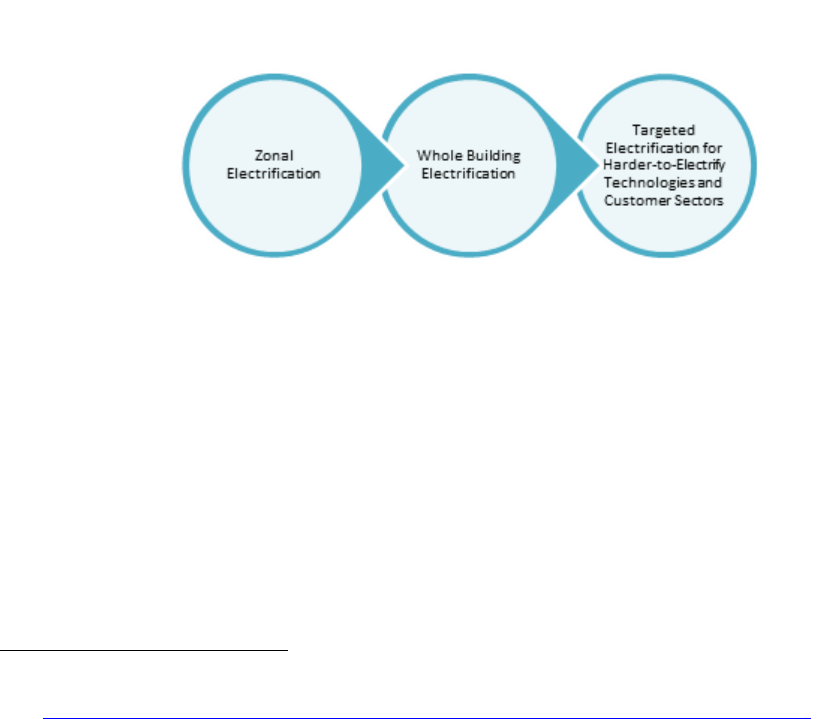

By leveraging zonal electrification or whole building 7

electrification approaches—rather than single appliance 8

incentives—PG&E can mitigate impacts to future gas system 9

costs and gas rates to facilitate an equitable transition to a 10

decarbonized future. Figure 1-4 below depicts this order of 11

preference for existing building electrification. Brief 12

explanations for each of those approaches is provided below. 13

FIGURE 1-4

PG&E’S PREFERRED ORDER FOR EXISTING BUILDING ELECTRIFICATION

1) Zonal electrification, also known as strategic 14

de-commissioning of the natural gas system, prioritizes 15

whole building electrification for entire regions. This 16

approach is guided by PG&E’s vision to preserve customer 17

affordability while maximizing emission reductions. The 18

approach uses PG&E data to identify zones with system 19

49

Found at:

https://www.energy.ca.gov/sites/default/files/2021-06/CEC-500-2019-055-F.pdf, p. iii.

(PG&E-1)

1-25

conditions and natural gas asset characteristics—such as, 1

but not limited to, age of assets, risks, number of customers, 2

and system throughput—that can provide insight about 3

locations that may warrant further engineering and/or 4

costing review for zonal electrification. While zonal 5

electrification is likely to have the best long-term outcome 6

for our customers, it requires highly targeted enrollment and 7

the complete electrification of all customers in a particular 8

“zone” to enable natural gas asset decommissioning. As a 9

result, while this might be the preferred approach, it may be 10

difficult to achieve. PG&E proposes new zonal 11

electrification placeholder programs to support a broader 12

enterprise strategy and investment into zonal electrification. 13

See Exhibit 2, Chapter 4, Section D.1 and D.2 for 14

information on PG&E’s new zonal electrification placeholder 15

programs. 16

2) Whole-building electrification focuses on replacing all 17

existing natural gas end uses within individual buildings or 18

groups of buildings with high-efficiency electric alternatives. 19

Whole-building electrification can help with long-term 20

affordability for participating customers as it removes 21

individual natural gas equipment and the associated PG&E 22

natural gas system operations and maintenance costs. 23

Additionally, whole-building electrification removes the need 24

for PG&E to provide natural gas service to the individual 25

electrified customer and therefore may make zonal 26

electrification easier in the future since there would be fewer 27

gas customers in an area to have to fully electrify. 28

3) Targeted electrification for harder-to-electrify technologies 29

and customer sectors focuses on the pursuit of partial 30

electrification of existing buildings when whole building 31

electrification is not possible or feasible. Certain 32

technologies such as cooking equipment may be 33

harder-to-electrify due to barriers such as customer 34

(PG&E-1)

1-26

preference, the higher cost of induction cooktops compared 1

to gas cooktops,

50

and may require changes to cooking 2

technique and kitchen layouts.

51

The CEC notes: 3

“even though gas cooking is only the third-largest 4

contributor to GHGs from homes, it contributes to the 5

need to extend gas lines to new homes and the reason 6

why some homeowners are reluctant to go 7

all-electric.”

52

8

Similarly, in commercial buildings, cooking accounts for less 9

than one-fourth of gas consumption in buildings.

53

As 10

such, targeted efforts focusing on cooking electrification 11

could have significant benefits (in the form of reduced gas 12

system costs) beyond those realized by the participating 13

customer. In instances when zonal or whole building 14

electrification is not possible, it may be beneficial to focus 15

efforts on electrifying appliances or other technologies 16

where possible areas during times when implementation 17

costs are lower, such as when customers are already 18

planning on replacing equipment upon failure or as a part of 19

all-electric new construction. However, as discussed in 20

Section E.1.b.3, PG&E is limited in its ability to focus its 21

funding for technology-based programs that can influence 22

availability of viable electric alternatives to gas appliances 23

and therefore intends to focus its funding on overcoming 24

other barriers through WE&T and C&S for these technology 25

areas. 26

PG&E includes several strategies and tactics to support 27

existing building electrification across these three approaches 28

50

California Building Decarbonization Assessment – Final Commission Report, CEC,

August 13, 2021, p. 82.

51

Ibid, p. 87.

52

Ibid, p. 86.

53

California Building Decarbonization Assessment – Final Commission Report, CEC,

August 13, 2021, pp. 30-31, Figure 7, citing California Commercial End Use Survey.

(PG&E-1)

1-27

that are discussed in more detail in Exhibit 2, Chapters 1 and 4. 1

These include: 2

• A new placeholder program for zonal electrification in the 3

equity segment for which PG&E intends to leverage the 4

CPUC’s AR and SEVI/SEVI-DAC

54

metrics to target this 5

program in geographic areas that include underserved and 6

vulnerable communities; 7

• Statewide new construction programs that support existing 8

building electrification by providing two pathways toward 9

whole-building electrification for retrofits by requiring either 10

the complete conversion to all-electric end uses and 11

removal of gas meters, or pre-requisites to dwellings and 12

buildings to be electric-ready if they are not yet able to fully 13

remove gas end-uses; and 14

• Local and statewide WE&T programs to reduce the barriers 15

customers face when considering fuel substitution for 16

gas-to-electric appliances. 17

b) New Building Electrification 18

Newly constructed buildings can have the lowest 19

decarbonization costs because there are no existing appliances 20

or infrastructure to remove or replace and electrification can be 21

a part of the design up front. PG&E’s strategy to address new 22

building electrification is centered around two key areas: 23

(1) statewide new construction programs and (2) C&S 24

programs. 25

PG&E is the lead program administrator for the statewide 26

new construction programs for the residential and 27

non-residential sectors. The statewide new construction 28

programs include a pathway for builders and developers to 29

pursue an all-electric option for newly constructed buildings that 30

are designed without any gas end-uses, therefore eliminating 31

54

SEVI-DAC is Socioeconomic Vulnerability Index-Disadvantaged Communities.

(PG&E-1)

1-28

the need for gas meters and natural gas service. See Exhibit 2, 1

Chapter 4, Section E.3 for more detail. 2

2) Technical Support and Advocacy Through C&S 3

While building decarbonization and electrification are important 4

tools in meeting California’s climate goals, there are significant 5

market barriers to achieving these policy initiatives through tangible 6

changes in the built environment. Advocating for advancements in 7

state, federal, and regional regulations can accelerate the transition 8

to low-carbon buildings and the use of appliances that have the 9

greatest decarbonization potential. PG&E has long been a leader in 10

building codes and appliance standards advocacy and providing 11

technical support to local jurisdictions and state agencies in EE. 12

PG&E expanded its C&S support to other areas including 13

decarbonization and water efficiency. 14

PG&E is the lead program administrator for the statewide C&S 15

programs. See Exhibit 2, Chapter 4, Section E.1, for PG&E’s C&S 16

strategies that support building decarbonization. This includes 17

coordination with new construction programs for enhanced data 18

collection to support future building codes and appliance standards, 19

a new local program focused on participating in building code and 20

appliances standard decarbonization rulemakings, supporting local 21

governments’ local energy ordinances (also known as reach codes) 22

through technical support, and code readiness and compliance 23

improvement programs that can support the building industry in its 24

building decarbonization efforts. 25

3) Decarbonize through Equipment Support 26

PG&E’s EE portfolio provides financial assistance in the form of 27

incentives and financing to encourage the adoption of energy 28

efficient end-use appliances. With the increased focus on building 29

decarbonization and the need for a managed transition from gas to 30

electric systems, there should be increased focus on the end-uses 31

through which those energy savings are delivered and a focus on 32

overall GHG reductions rather than energy savings alone. 33

(PG&E-1)

1-29

Limit Natural Gas Equipment Support 1

It is important to support a building decarbonization transition 2

that is rooted in equity and affordability for customers. PG&E 3

recognizes the unique needs of certain customers, such as those in 4

the industrial and agricultural sectors, that rely on natural gas to 5

power core business practices and therefore may be unable to 6

electrify their buildings or equipment. In these situations, PG&E can 7

work closely with those customers to deliver opportunities to reduce 8

their energy use and carbon footprint without disruptions to their 9

core operations. For other customer sectors, by the end of the 10

eight-year business plan period, PG&E anticipates limiting its 11

financial support for long-life gas equipment except where there is 12

no viable alternative.

55

13

Incorporate Low-GWP Refrigerants. 14

Pursuant to the Energy Division template, PG&E provides this 15

information regarding incorporating low-GWP refrigerants. PG&E 16

recognizes the impact refrigerants from space and water heating 17

equipment have on emissions in the building sector

56

and the need 18

to address those emissions in the pursuit of carbon neutrality. 19

PG&E uses the Commission’s Refrigerant Avoided Cost Calculator 20

55

In instances where PG&E has limited ability to impact funding decisions on equipment

support, such as for statewide programs for which PG&E is not the lead program

administrator, funding may continue for long-life gas equipment in PG&E’s territory.

D.18-05-041 (pp. 185-186, OP 18) directed that the lead program administrator for each

statewide program shall have sole responsibility for the program. PG&E is not the lead

for any technology-based statewide programs.

56

From CARB (https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/resources/documents/high-gwp-refrigerants.):

“Global Warming Potential, or GWP, is a measure of how destructive a climate

pollutant is. Refrigerants today are often thousands of times more polluting than

carbon dioxide (CO

2

). The GWP of a gas refers to the total contribution to global

warming resulting from the emission of one unit of that gas relative to one unit of the

reference gas, CO

2

, which is assigned a value of 1. GWPs can also be used to

define the impact GHG gases will have on global warming over different time periods

or time horizons. These are usually 20 years, 100 years, and 500 years. A time

horizon of 100 years is used by regulators (e.g., the California Air Resources

Board).”

(PG&E-1)

1-30

to guide its use of low-GWP refrigerant measures in the portfolio 1

forecasts of this application.

57

2

PG&E can address barriers to adoption of low-GWP refrigerant 3

measures through WE&T. PG&E also intends to support the 4

adoption of low-GWP appliances into California’s building code, as 5

well as in regulations to be adopted by the Environmental Protection 6

Agency, CARB, and other California state agencies as appropriate. 7

Further details on PG&E’s strategies to incorporate low-GWP 8

refrigerants into its EE portfolio can be found in Exhibit 2, Chapter 1, 9

Section C.2. 10

c. Strategy #3: Deploy Technologies That Are Grid-Responsive and 11

Demand Flexible 12

As PG&E looks forward to a grid powered by variable, renewable 13

generation that may be operated by PG&E, another non-utility load 14

serving entity, or even other customers through Distributed Energy 15

Resources (DER),

58

we recognize that our EE portfolio must provide 16

solutions to match these evolving grid characteristics to continue to 17

provide our customers with safe, reliable, affordable, and clean energy. 18

PG&E offers the following tactics to operationalize this strategy. 19

1) Align the EE Portfolio With PG&E’s Enterprise-Wide 20

Coordinated Supply and Load Strategy 21

PG&E recognizes that our electric system needs the right 22

resources, in the right places, at the right times to adapt to changing 23

grid conditions. These needs include more flexible resources to 24

accommodate greater amounts of renewable generation, more 25

distributed resources at appropriate locations on the electric grid, 26

and a cost-effective pathway to implementing these changes. 27

PG&E’s customers need to be a part of this solution, with clear 28

57

D.21-05-031, OP 16.

58

DERs can be defined as:

“…distribution-connected distributed generation resources such as energy efficiency,

demand response, customer generation (e.g., rooftop solar), energy storage,

alternative fuel vehicles (e.g., electric vehicles), and water-energy conservation.”

Source: https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/demand_side/.

(PG&E-1)

1-31

pathways to engage in the full spectrum of load management 1

programs and electric rate products that allow them to utilize the full 2

potential of their DERs.

59

3

PG&E is working to implement an enterprise-wide coordinated 4

supply and load strategy to accomplish these needs, and intends to 5

position our EE portfolio to play a key role in delivering both: 6

a) A cohesive, accessible, and clear customer experience; and 7

b) A comprehensive, innovative, customer energy management 8

portfolio strategy. 9

2) Utilize the Meter-Based Platform Throughout our Portfolio 10

Pursuant to the Energy Division template, PG&E provides 11

information on its strategies to use savings forecasting and 12

quantification methods such as NMEC where cost-effective and 13

feasible. PG&E refers to approaches to calculating savings and 14

TSB using metered customer energy usage data (meter data) as the 15

meter-based platform. The meter-based platform comprises three 16

primary approaches: NMEC, strategic energy management, and 17

experimental or quasi-experimental methods. 18

Meter-based approaches can play a key role in PG&E’s EE 19

portfolio in several ways. First, they can enable more granular 20

measurement and targeting of EE savings. They can accomplish 21

this by measuring the impact of programs on the customers 22

participating (rather than relying on average values), and by 23

providing regular feedback to implementers and customers about 24

program impacts. Feedback can both support load flexibility and 25

help to identify if an intervention is not working. Second, 26

meter-based approaches can enable projects that are more 27

challenging, or not possible, to pursue through approaches that rely 28

on engineering calculations. Meter-based approaches measure 29

59

By full potential, PG&E means utilizing DERs to reduce, shift, or shape usage in

response to customer or grid needs or electric retail rates.

(PG&E-1)

1-32

savings from the existing conditions

60

of a customer’s building, and 1

therefore enable programs to target “stranded potential”

61

and 2

capture the impact of behavioral, operational, and 3

retrocommissioning interventions. Meter-based approaches also 4

capture the impact at the meter of whole-building or whole-system 5

interventions, and in doing so can support deeper-savings projects. 6

Finally, as meter-based approaches continue to evolve, they may 7

facilitate integration with other DERs (e.g., DR and energy storage) 8

by measuring the overall impact from all demand-side interventions 9

on energy usage from the grid. PG&E envisions continuing to 10

expand the use of meter-based approaches where these 11

measurement methods are cost-effective and feasible to measure, 12

pay for, and claim EE savings. 13

d. Strategy #4: Contribute to Cost Saving Resiliency Solutions for 14

Customers 15

PG&E intends to leverage our EE portfolio to support solutions that 16

increase customer resiliency. Load reductions achieved when 17

implementing EE interventions may be able to deliver cost savings to 18

individual participants and all customers when incorporated into the 19

scope of a resiliency solution project. PG&E offers two tactics to 20

operationalize this strategy. 21

60

Information on EE baselines including existing conditions and code baselines can be

found here:

https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/industries-and-topics/electrical-energy/demand-side-managem

ent/energy-efficiency/energy-efficiency-baselines.

61

The Energy Efficiency Potential and Goals Study for 2018 and Beyond defines stranded

potential as:

“the opportunities for energy efficiency that are not currently captured by either PA

rebate programs or codes and standards. Stranded Potential is below code savings

that is not materializing in the market because there is no incentive for the customer

to upgrade their existing equipment given current program rebate policy. Under

AB802, PAs could start offering rebates for bringing existing equipment up to code

thus motivating a whole new subset of customers to install energy efficiency and

capturing the Stranded Potential.”

Navigant, Energy Efficiency Potential and Goals Study for 2018 and Beyond, p.4, Aug.

23, 2017.

(https://docs.cpuc.ca.gov/PublishedDocs/Efile/G000/M194/K614/194614840.PDF , last

accessed Feb. 9, 2022).

(PG&E-1)

1-33

1) Use EE to Reduce Customer Costs for Resiliency Solutions 1

PG&E’s Wildfire Mitigation Plan (WMP)

62

plans for the 2

construction and operation of microgrids and remote grids as 3