TENTATIVE MANUAL

FOR

EXPEDITIONARY ADVANCED

BASE OPERATIONS

2

ND

EDITION

MAY 2023

DE

PARTMENT OF THE NAVY

HEADQUARTERS, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS

D

ISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited.

HEADQUARTERS

UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20350-3000

PRIMARY REVIEW AUTHORITY: DC CD&I

RECORD OF CHANGES

NUMBER

DATE

ENTERED BY

P

CN 501 007704 00

INTENTIONALLY BLANK

i

DE

PARTMENT OF THE NAVY

Headquarters, United States Marine Corps

Washington, DC 20350-3000

9 May 2023

F

OREWORD

O

VERVIEW

The Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (TM EABO) was developed as part

of an iterative process to test, refine, and codify the classified Concept for Expeditionary Advanced Base

Operations (EABO), signed in March 2019 by the Commandant of the Marine Corps and Chief of Naval

Operations, as well as to inform force design and development. This second edition of TM EABO

includes updated information and captures lessons from war games, exercises, experiments, and other

analysis to describe how naval forces will conduct EABO across the competition continuum. The

information contained herein is therefore authoritative but not definitive; it provides the official baseline

of ideas to be further tested and codified in doctrinal publications.

PU

RPOSE

Marine Corps concepts propose new and innovative approaches for addressing current or future gaps,

shortfalls, or challenges for which existing methods or capabilities are ineffective, insufficient, or

nonexistent. The original EABO concept must be read to understand and properly apply the new

approaches called out in the TM. This manual was written to serve three primary functions:

1) Educate the Fleet Marine Force (FMF) on the missions of, and the forces that conduct, EABO

2)

F

acilitate live force experimentation to test and refine force structure and capabilities

3)

D

rive action for future force development and serve as a foundation to move from learning t

o

execution, including the expansion into formal naval doctrine

SC

OPE

This manual describes the general characteristics and terms of EABO and provides planning

considerations and options for force and battlespace organization. As a result of the dedicated efforts to

implement Force Design 2030 over the past few years, the FMF has made great strides towards

conducting EABO as envisioned within the approved concept. As an example, at the time of this writing

3rd Marine Littoral Regiment (MLR) within III MEF is at initial operating capability (IOC). This manual

lays out factors and objectives for continued experimentation and assessment of force structure and

capabilities associated with the MLRs, other task organized MAGTFs, and the naval vessels envisioned to

support and sustain them. Included are considerations for command arrangements, as well as a series of

cross-functional topics for exploration.

T

he tentative manual is meant as a reference manual; it is not designed to be read from cover to cover. It

is recommended that all readers complete chapters 1, 2, and 7 along with their given functional interest in

chapters 3-6.

• Chapter 1: Introduces Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations.

• Chapter 2: Addresses EABO planning and organizational considerations and provides a primer

on the Navy Composite Warfare Commander (CWC) construct as an example for new tactica

l

c

ommand relationships.

• Chapters 3-6: Explores functional considerations in the areas of Intelligence, Information,

A

viation, and Logistics.

• Chapter 7: Focuses on utilizing EABO to support integrated littoral operations

.

B

ased on feedback since its original publication in February 2021, notable changes, updates and

inclusions have been made to this version including: expanding on the impact of irregular adversary

ii

forc

es and local populations within host countries; stressing the criticality of effective partnering

including in the information environment; and aviation ordnance and forward arming and refueling

considerations, especially in regards to the ability to service a variety of Navy systems that Marines are

not currently trained or equipped to support. Most notably, the aviation and logistics communities have

extensively rewritten chapters 5 and 6. These additions have made this version more comprehensive

than the original, and it is our expectation that Marines and Sailors will continue to test and implement

EABO ideas and capabilities based off this latest revision.

NEXT S

TEPS

EABO directly links with the Commandant’s Planning Guidance and Force Design 2030 and aligns to

four of the six USN Force Design Imperatives in NAVPLAN 22. This edition of the TM will be used by

FMF units to conduct further live, virtual, and constructive force experimentation that validate, refine, and

develop warfighting capability and generate best practices for tactics, techniques, and procedures as the

concept moves beyond development to implementation.

Vali

dated best practices should be incorporated into the Service’s doctrinal publications as Marine Corps

tactical publications (MCTPs) or Marine Corps reference publications (MCRPs). Marine Corps task

revisions should codify EABO for core and assigned mission essential tasks across the FMF as

applicable. Tested and validated solutions should be submitted for follow-on capabilities planning and

entered into annual POM plan development. In the future, elements of all MAGTFs should be trained for

sea denial operations.

Reviewed and approved this date.

KARSTEN S. HECKL

Lieutenant General, US Marine Corps

Deputy Commandant for Combat Development and Integration

PCN

501 007704 00

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited.

i

ii

T

his manual is dedicated to the late

C

olonel Arthur J. Corbett, USMC (Ret.)

w

ho served the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory for ten years after leaving active duty. He was a

visionary, mentor, enthusiastic proponent of expeditionary advanced base operations, and good shipmate

to all hands. He challenged us to embrace disruptive thinking and changing paradigms.

iv

I

NTENTIONALLY BLANK

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword ................................................................................................................................... i

Dedication ................................................................................................................................ iii

Chapter 1 Introduction to Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations .............................. 1-1

1.1 General ....................................................................................................................................... 1-1

1.2 Operational Context ................................................................................................................... 1-2

1.3 Foundations of Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations ....................................................... 1-2

1.4 Characteristics of Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations .................................................... 1-4

1.5 Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations Across the Competition Continuum ....................... 1-4

1.6 Relationship to Instruments of National Power ......................................................................... 1-5

Chapter 2 Approach to Planning and Organization ............................................................ 2-1

2.1 General ....................................................................................................................................... 2-1

2.2 Planning Context for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations .............................................. 2-1

2.3 Inherent and Prescribed Conditions of Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations ................... 2-2

2.4 Planning Framework .................................................................................................................. 2-3

2.5 Naval Command and Organizational Considerations ................................................................ 2-4

2.6 Framework for Decentralized Execution ................................................................................... 2-5

2.7 Command and Control ............................................................................................................. 2-12

Chapter 3 Intelligence Operations ....................................................................................... 3-1

3.1 General ....................................................................................................................................... 3-1

3.2 Purpose and Scope ..................................................................................................................... 3-2

3.3 Intelligence-Led Operations ....................................................................................................... 3-2

3.4 Naval and Joint Force Integration .............................................................................................. 3-3

3.5 Operational Environment ........................................................................................................... 3-4

3.6 Integrated Naval Intelligence Process ........................................................................................ 3-8

Chapter 4 Information Activities in Support of EABO ........................................................ 4-1

4.1 General ....................................................................................................................................... 4-1

4.2 Purpose and Scope ..................................................................................................................... 4-1

4.3 Information Environment Basics ............................................................................................... 4-1

4.4 Information Warfighting Function ............................................................................................. 4-2

4.5 Creating and Exploiting Information Advantages ..................................................................... 4-8

4.6 Information Maneuver Forces .................................................................................................. 4-11

4.7 Alignment and Integration of Information in EABO ............................................................... 4-13

4.8 Authorities ................................................................................................................................ 4-14

Chapter 5 Aviation Operations ............................................................................................. 5-1

vi

5.1 General ....................................................................................................................................... 5-1

5.2 Purpose and Scope ..................................................................................................................... 5-1

5.3 Role of Aviation in Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations ................................................. 5-1

5.4 Air Direction, Air Control, and Airspace Management ............................................................. 5-3

5.5 Functions of Aviation in Support of Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations ...................... 5-3

5.6 Littoral Force Aviation Combat Element Supporting Relationships ......................................... 5-5

5.7 Littoral Force Aviation Combat Element Relationships with the Joint Force ........................... 5-6

5.8 Littoral Air Command and Control ............................................................................................ 5-6

5.9 Aviation Ground Support ........................................................................................................... 5-9

5.10 Aviation Planning .................................................................................................................... 5-10

Chapter 6 Logistics Operations ........................................................................................... 6-1

6.1 General ....................................................................................................................................... 6-1

6.2 Logistics in the Competition Continuum ................................................................................... 6-1

6.3 Tactical-level logistics ............................................................................................................... 6-1

6.4 Operational-level logistics ....................................................................................................... 6-13

6.5 Strategic-level Logistics ........................................................................................................... 6-19

6.6 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 6-21

Chapter 7 Littoral Operations ............................................................................................... 7-1

7.1 General ....................................................................................................................................... 7-1

7.2 Concept of Operations ............................................................................................................... 7-1

7.3 Plan of Execution ....................................................................................................................... 7-1

7.4 Common Phasing Considerations .............................................................................................. 7-3

7.5 Mission Concepts of Employment ............................................................................................. 7-8

7.6 Fleet Interoperability ................................................................................................................ 7-14

Appendix A Future Force Design and Considerations ....................................................... A-1

Appendix B Mission-Essential Tasks .................................................................................. B-1

Appendix C Experiment Objectives ..................................................................................... C-1

Appendix D Abbreviations ................................................................................................... D-1

Appendix E Glossary ............................................................................................................ E-1

vii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 2-1. Notional naval task organization…………………………………………………………..…2-4

Figure 2-2. Notional composite warfare organization……………………………………………….....…2-6

Figure 2-3. Littoral operations areas in the context of composite warfare……………………………....2-10

Figure 2-4. Notional littoral operations area……………………………………………………………..2-11

Figure 2-5. Navy supporting situations………………………………………………………………….2-13

Figure 3-1. All domain environment………………………………………………………………….…..3-4

Figure 3-2. The littoral environment………………………………………………………………….…..3-6

Figure 5-1. Proposed functions of Marine aviation……………………………………………………….5-4

Figure 6-1. Sustainment web example……………………………………………………………………6-1

Figure 6-2. “Concentric Circle” Sourcing Logic…………………………………………………….……6-2

Figure 6-3. Spectrum of Forward Provisioning…………………………………………………….……..6-3

Figure 6-4. Supporting capabilities……………………………………………………………………….6-6

Figure 6-5. Notional force closure—advanced naval base through intermediate staging base……….....6-15

Figure 6-6. Notional maneuver into littoral operations area……………………………………….…….6-15

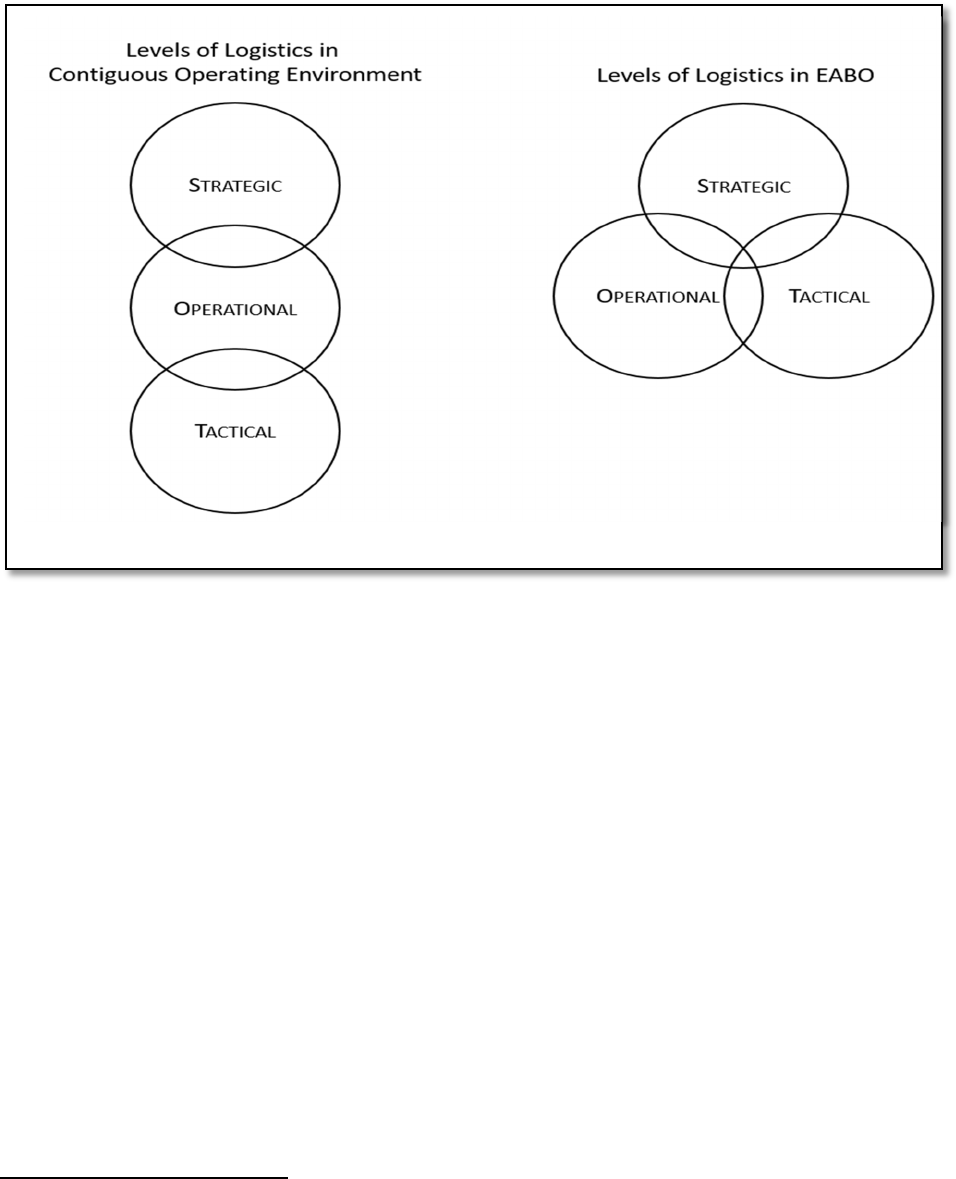

Figure 6-7. Conceptual models for levels of logistics…………………………………………….……..6-19

Figure 7 1. Notional concept of employment for maritime fires…………….……………..………..…...7-9

Figure 7-2. Notional surface warfare unit of action delivers fires……………………………………….7-10

Figure 7 3. Notional AAW unit of action intercept…………………………..………………………….7-11

Figure A-1. Notional Organization of the 2030 MLR .............................................................................. A-1

Figure A-2. Notional Organization of the LCT ........................................................................................ A-2

Figure A-3. Notional Organization of the MLR CLB ............................................................................... A-3

Figure A-4. Notional Organization of the LAAB ..................................................................................... A-4

Figure A-5. Notional Organization of the 2030 infantry battalion ........................................................... A-5

Figure A-6. Notional Organization of the 2030 infantry company ........................................................... A-5

viii

INTENTIONALLY BLANK

1-1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION TO EXPEDITIONARY ADVANCED

BASE OPERATIONS

1.1 GENERAL

In 2019, the Commandant of the Marine Corps and the Chief of Naval Operations approved the Concept

for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO), a foundational naval concept to address

challenges created by potential adversary advantages

in geographic location, weapons system range,

precision, and capacity. It also created opportunities

by improving our own ability to maneuver and

exploit control over key maritime terrain, fully

integrating Fleet Marine Force (FMF) and Navy

capabilities to enable sea denial and sea control, and

support sustainment of the fleet. EABO was tightly

coupled and published in a planned sequence with the

Navy’s Concept for Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) and is aligned to the ideas presented in the

Joint Warfighting Concept (JWC.) Together, EABO and DMO advocate for integrated yet distributable

naval formations to support sea denial and sea control in the face of potential adversaries who pose

increasing challenges to current naval forces.

Since releasing the Tentative Manual for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (TM EABO) in 2021,

the Marine Corps conducted multiple war games, exercises, experimentation, and other analyses to further

develop and validate the central and supporting ideas. Other concepts, such as A Concept for Stand-In

Forces (SIF)

and A Functional Concept for Maritime Reconnaissance and Counter-reconnaissance

1

were

approved to describe how Marines will be positioned forward at expeditionary advanced bases (EABs),

shoulder-to-shoulder with our allies and partners, leveraging all-domain tools as the eyes and ears of the

fleet and joint force. The SIF concept complements this version of the TM by describing capabilities and

methods essential for forces conducting EABO. Designed to persist forward alongside allies and partners

within a contested area, SIF can operate from EABs to leverage all-domain tools as the eyes and ears of

the fleet and joint force. Stand-in forces complement the low signature of EABs with an equally low

signature force structure. SIF have the enduring tasks of conducting reconnaissance and counter-

reconnaissance at every point on the competition continuum and conducting sea denial when required in

support of the naval campaign.

This updated tentative manual sets forth pre-doctrinal considerations for forces conducting expeditionary

advanced base operations. Its provisions are applicable in varying degrees to all related situations, task

organizations, tactics, techniques, and procedures. The specific missions, available means, and other

variables of the operational environment (OE) will necessitate adjustments to the provisions as discussed

in subsequent chapters and as we begin implementing EABO.

1

Headquarters, US Marine Corps, A Concept for Stand-In Forces (2019); Deputy Commandant, Combat

Development and Integration, A Functional Concept for Maritime Reconnaissance and Counter-reconnaissance

(2022)

The FMF conducts a variety of missions,

most prominently afloat forward

presence, crisis response, and all forms

of amphibious operations. Thus, the

FMF as a whole is capable of EABO

rather than designed exclusively for

EABO.

1-2

1.2 OPERATIONAL CONTEXT

For a generation, contemporary US force design and capability development modeled under three core

assumptions: presumptive or readily achieved sea control, air superiority, and assured communications.

However, as stated in Marine Corps doctrinal publication (MCDP)-1, "…advantages gained by

technological advancement are only temporary, for someone will always find a countermeasure, tactical

or itself technological, which will lessen the impact of the technology."

Continual rapid technological advancement and increases in the lethality, range and accuracy of potential

adversaries’ fielded weapons systems challenge US conventional military superiority and require the US

military to continually reevaluate how it supports global power projection. Global competitors are

increasingly fielding stand-off engagement capabilities - long-range systems designed to keep US forces

out of key operating areas and push them farther from overseas allies and partners while minimizing risk

to their own forces. This challenge is significant and cannot be met by merely refining current methods

and capabilities - doing so would only delay the inevitable as adversaries only need to invest in slightly

longer-range systems to regain the stand-off engagement advantage. Simply put, defeating this adversary

strategy is not possible through an endless cycle of long-range one-upmanship, it requires a different

strategy to regain the initiative.

Potential adversaries can also bring to bear advanced technologies during competition below armed

conflict through irregular forces or proxies. These irregular forces can employ non-technical means to

counter our conventional superiority, using elements of the population to gain information on Marine

locations, composition, disposition, and strength. They can influence friendly and neutral networks in

areas occupied by littoral forces to create unrest.

1.3 FOUNDATIONS OF EXPEDITIONARY ADVANCED BASE OPERATIONS

EABO provide engagement opportunities throughout the competition continuum and are a visible and

tangible reminder of our Nation’s resolve for friends and foes alike. Forces conducting EABO combine

various forms of operations to persist within the reach of adversary lethal and nonlethal effects, changing

their risk calculations. It is critical that the

composition, distribution, and disposition of these

forces limit the adversary’s ability to target them,

engage them with fires and other effects, and

otherwise influence their activities.

Naval forces execute EABO throughout the

competition continuum to deter aggression, set

conditions within the theater before armed

conflict occurs, and swiftly posture to fight within

the maritime environment during a joint

campaign. Advantageous force posture can be leveraged to disproportionately draw or distract enemy

forces, or create dilemmas, which enable fleet forces to mitigate risk in a contested environment or seize

opportunities elsewhere. The mobile and distributed nature of EABO imposes difficult choices upon the

competitor and provides a force able to adapt and regenerate more quickly. The operating environment is

likely one where the littoral force conducting EABO will be at a disadvantage in numbers of personnel

and weapons, and proximity to interior lines. Additionally, living among, or near, the local population

increases vulnerability to irregular threats from malign actors and adversary proxy forces. To succeed in

this environment, commanders must promote an alert mindset that keenly balances risk to mission and

risk to force, while seeking decisive engagement when it enables the fleet as part of the larger campaign.

EABO are a form of expeditionary warfare

that involve the employment of mobile, low-

signature, persistent, and relatively easy to

maintain and sustain naval expeditionary

forces from a series of austere, temporary

locations ashore or inshore within a

contested or potentially contested maritime

area in order to conduct sea denial, support

sea control, or enable fleet sustainment.

1-3

The true advantage of EABO lie in the ability to support the projection of naval power by integrating with

and supporting the larger naval campaign. Conceptually, naval expeditionary forces operating from the

landward portion of the littoral, combined with the fleet’s ability to operate seaward and in the airspace,

in cyberspace, and in the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) - give naval commanders the ability to operate

in all five dimensions of the littorals (including: seaward [both surface and subsurface], landward [both

surface and subterranean], the airspace above, cyberspace, and the EMS) in the maritime domain.

2

Given

these organic capabilities, along with access to space-based capabilities, naval forces have the ability to

gain and regain advantage in all-domain operations.

The desired end state for EABO is to contribute to integrated deterrence through Marine Forces that are

structured and ready to persist, partner, survive, and fight effectively across an expanded maneuver space

as a ready, capable, and combat-credible forward force. These forces will be capable of supporting the

joint force commander (JFC) by:

• Establishing persistent sea denial capabilities forward to deter and, if necessary, blunt aggression in

the littorals;

• Contributing to sea control;

• Conducting security cooperation activities to shape the operating environment by building

partnerships, deter hostilities, counter malign behavior, and set conditions to achieve national

security objectives;

• Contributing to fleet battlespace awareness;

• Supporting and, if directed, integrating with other joint, allied, and partner forces; and

• Refueling, rearming, and replenishing ships and aircraft in austere forward areas.

EABO missions include:

•

Support sea control operations

•

Conduct sea denial operations within the littorals

•

Contribute to maritime domain awareness

•

Provide forward command, control, communications, computers, combat systems, intelligence,

surveillance, reconnaissance, targeting (C5ISRT), and counter-C5ISRT capability

•

Provide forward sustainment to support and enable the joint force, and partners and allies

EABO tasks include:

•

Conduct surveillance and reconnaissance

•

Generate, preserve, deny, and/or project information

•

Conduct screen/guard/cover operations

•

Deny or control key maritime terrain

•

Conduct surface warfare operations

•

Conduct air and missile defense (AMD)

•

Conduct strike operations

•

Conduct antisubmarine warfare (ASW)

•

Conduct sustainment operations

•

Conduct forward arming and refueling point (FARP) operations

•

Conduct security cooperation

•

Conduct Irregular Warfare (IW)

2

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and Headquarters, US Marine Corps, Littoral Operations in a Contested

Environment (Washington, DC: US Department of the Navy, 2017).

1-4

1.4 CHARACTERISTICS OF EXPEDITIONARY ADVANCED BASE OPERATIONS

Stand-in. EABO provide stand-in engagement opportunities throughout the competition continuum.

During campaigning, forces conducting EABO engage allies and partners and their neutral civilian

networks, counter threat networks, preserve access, and shape the theater for future operations. EABO

also enables the persistent posturing of littoral forces within a potential adversary’s tactical weapons

engagement zone (WEZ) before conflict. During armed conflict, the combination of stand-in and stand-

off engagement capabilities places the adversary on the horns of a dilemma: while the adversary seeks to

discover and engage friendly stand-off forces, he exposes himself to the sensing, nonlethal, and lethal

capabilities of stand-in forces.

Mobile. Forces conducting EABO have the organic resources and platforms sufficient to transit within a

theater and conduct tactical maneuver across the seaward and landward portion of the littoral to

accomplish assigned missions. Existing naval, joint, and allied/partner bases and stations in the theater

also play an important role to project, sustain, and recover forces conducting EABO.

Persistent. Forces conducting EABO persist forward by moving with a high degree of flexibility within

areas of key maritime terrain, presenting a light posture, sustaining themselves in an austere setting, and

protecting themselves from detection and targeting. EABO diminish the reliance on fixed bases and

easily targetable infrastructure.

Low Signature. Forces conducting EABO carefully manage signatures at all times, especially while

conducting localized movement and maneuver. This allows them to remain positioned to achieve the

desired operational effects while complicating adversary efforts to find and target them. During

campaigning, utilizing military assets for movement and maneuver can make Marine forces easier to find

and target by adversary irregular means and forces. Where feasible, forces should leverage host nation

(HN) government and commercial assets to perform select support functions and reduce their reliance on

external sustainment.

Integrated. The assigned mission sets within EABO are conducted within a joint and coalition

framework, part of not merely an interoperable, but an integrated naval force. Task-organized Marine and

Navy units project naval power through EABO by fusing their landward and seaward roles. For the

purpose of this tentative manual, integrated naval units executing assigned tasks within and from EABs

are referred to as littoral forces. Littoral forces do not connote a specific unit or formation. However,

once task-organized as true blue-green teams, littoral forces embody the characteristics of EABO and

persist within contested areas as they apply all available means to accomplish their missions.

Cost-effective. A stand-in force executing EABO is strategically cost-effective by virtue of its ability to

undermine a potential adversary’s cost-imposition strategy. Potential adversaries are investing in large

numbers of comparatively inexpensive systems of adequate lethality, extended range, and greater

precision to hold at risk the US military’s expensive, sophisticated, and relatively few multi-mission

platforms. Forces executing EABO are small, numerous, dispersed, relatively simple to maintain, and

difficult to target, thus inverting an adversary’s cost-benefit calculation when deciding whether to engage

and upsetting the cost-imposition strategy.

1.5 EXPEDITIONARY ADVANCED BASE OPERATIONS ACROSS THE COMPETITION

CONTINUUM

EABO provide value across the competition continuum through opportunities to conduct persistent

engagement with partners and deter adversaries, which is a fundamental aspect of international relations.

Within the aspect of cooperation, we undertake activities within EABO as a cooperative effort with like-

minded nations during pre-conflict campaigning as a means of gaining and maintaining access,

1-5

developing/enhancing allies’ and partners’ capabilities and increasing their interoperability with the joint

force, countering malign behavior, and deterring regional aggression. The most common applications of

EABO in this context involve contributing to regional surveillance to inform and support diplomatic,

informational, military, and economic counteraction to violations of international norms. Cooperative

activities may also include increasing familiarity with potential operating areas, collaborating in

development and fielding of common equipment and materiel solutions, improving infrastructure,

conducting exercises that build relationships and enhance collective warfighting capabilities, promoting

deterrence, and supporting law enforcement against actions that violate HN or international laws.

Forces conducting EABO are designed to accomplish military objectives inside the WEZ, while

decreasing risk to major fleet units, in support of the overall fleet concept of operations. In the event of

crisis, naval forces conduct EABO to augment, enhance, or assist partner nations in defending

sovereignty, controlling key maritime terrain, and contesting adversary fait accompli gambits.

3

In the

event of conflict, naval forces conduct EABO to deny enemy freedom of action, impose costs, and shape

the OE in support of integrated sea control and maritime power-projection operations.

1.6 RELATIONSHIP TO INSTRUMENTS OF NATIONAL POWER

Strategic competition requires coordinating efforts among all instruments of national power: diplomatic,

informational, military, and economic (DIME).

4

These instruments must be mutually supporting,

leverage all available capabilities across government, and contribute to the creation of effects in all

domains. The Naval Service remains the preeminent US military component for sustained power

projection, and a littoral force conducting EABO is a key enabler to a naval campaign. In the current

environment, every action may affect multiple instruments of national power across the spectrum of

conflict. Operational planning must consider these impacts, and the coordination among agencies and

nations must be consistent and continuous.

1.6.1 Diplomatic

Diplomatic efforts can facilitate future EABO through mechanisms such as basing and staging rights,

status of forces agreements (SOFAs), increased information sharing or other supporting HN agreements.

These cooperative actions can also facilitate campaigning by providing diplomatic efforts with a forward-

positioned US force that can reassure allies and partners, project power, develop HN capabilities, and

provide credible deterrence options that enable discussions and negotiations.

1.6.2 Informational

EABO provide an opportunity to generate and project information within the information environment

(IE), providing a means to convey intent, build relationships, promote partnerships, and undermine

adversary efforts. By leveraging the information warfighting function, the commander of littoral forces

enables strategic messaging and creates or exploits opportunities that support tactical and operational

objectives. Information in EABO will be discussed further in chapter 4.

1.6.3 Military

The inherent mobility and persistent presence of forces conducting EABO enable joint force access and

the ability to posture in international waters adjacent to friends, partners, competitors, and other actors.

The effects produced by littoral forces are relevant for competition across the spectrum of conflict. These

3

Per Webster’s II New Riverside University Dictionary, a fait accompli is “an accomplished and presumably

irreversible deed or fact.”

4

Joint Chiefs of Staff, Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States, JP 1 (Washington, DC: US Department

of Defense, 2017).

1-6

effects influence the calculus of both friends and adversaries, by improving the US strategic position with

increased presence in a contested area or by reducing force size in a given area.

1.6.4 Economic

The Naval Service may execute EABO in conjunction with US employment of the economic instrument

of power. This requires collaborative planning with interagency partners as well as private enterprises.

When cooperating with partners, the use of local contractors for logistical support can improve the US

position in a region and counter a competitor's move to sideline US forces. Economic incentives can

facilitate long-term security cooperation and ensure the availability of dual-use facilities such as sufficient

harbors, docks, and bases. If planned effectively, these investments in foreign-nation infrastructure will

potentially enhance US influence and set conditions for future operations.

2-1

CHAPTER 2

APPROACH TO PLANNING AND ORGANIZATION

2.1 GENERAL

The role of the commander of littoral forces, at every level, is to develop and exploit opportunities

through bold action. Given human nature, commanders may have a natural inclination to employ larger

formations to ensure mission accomplishment while enhancing self-defense. However, the virtues of

smaller, more numerous, and more dispersed formations offer inherent force protection against an

adversary with pervasive sensors and long-range precision weapons. Capitalizing on these attributes,

commanders are able to employ well-placed, disciplined units across the littorals to achieve effects

without resorting to traditional concentration of forces, which poses a credible threat to potential

adversaries.

The complexity and danger found in EABO require the mental rigor to plan effectively and set the

conditions for success not only during conflict but also before conflict begins. A littoral force is only

relevant if it maintains the ability to apply force at the time necessary to generate options and influence

the greater campaign. Operating in a distributed

environment with limited support and resources will

require an agile force with a critical-thinking mindset,

demonstrating the mental agility to rapidly shift

perspectives and generate alternatives.

Commanders must develop a campaigning mindset to

effectively employ EABO not only in armed conflict,

but also in competition and crisis. The cultivation of

a campaigning mindset in planning, characterized by long-term thinking and coordination with allies and

partners, increases political-military options while also presenting potential adversaries with increasing

dilemmas. Campaigning across the competition continuum also demands more effective and complete

naval integration.

Planning for, and possibly forming, naval task formations out of standing MAGTF organizations is a

complex task. To achieve decision advantage it is essential to formalize and rehearse these transitions

before a conflict occurs. To deliver the full potential of EABO and achieve desired effects, the traditional

roles of blue and green components of a naval force must evolve. Command arrangements and functions

must no longer restrict Navy components to seaward contributions and Marine Corps components to

landward contributions to naval operations and power projection. Complete integration of naval forces

conducting EABO requires an appreciation of the importance of integrating landward and seaward

activities under fleet cognizance to achieve effects in all domains.

2.2 PLANNING CONTEXT FOR EXPEDITIONARY ADVANCED BASE OPERATIONS

The environment in which littoral forces will conduct EABO is both complex and dynamic. The

commander must plan to operate across multiple domains and within the adversary’s WEZ. Planning

procedures require detailed integration and coordination at all echelons prior to conflict. Understanding

the planning implications and requirements gained through analysis of the strategic environment,

direction, and guidance is critical to ensuring mission success. Coordinating littoral force actions in the

Thorough planning and execution are

critical to reducing risk to mission and

risk to force. Leaders and Planners

must consider safety and integrate risk

management controls in every phase of

planning and execution to help ensure

successful EABO operations.

2-2

complex time, space, and geography of the littorals requires intricate planning, especially given the

changing naval and joint force environment.

All planning efforts must seek to shape the general conditions of competition over an extended period of

campaigning to be responsive to escalation and successful in armed conflict. It is important that planning

factors include methods to de-escalate situations to prevent or deter armed conflict. De-escalation

activities could include using intermediate force capabilities; generating, preserving, denying or

projecting information; or other nonlethal options to counter adversary objectives while avoiding

escalation.

2.3 INHERENT AND PRESCRIBED CONDITIONS OF EXPEDITIONARY ADVANCED

BASE OPERATIONS

Littoral forces conduct EABO under the following inherent conditions and requirements:

• Task organization must be flexible, as task-organization requirements will vary depending on

whether the forces are embarked, landing, or conducting operations within EABs ashore.

• Littoral forces must disperse as widely as possible to enable force protection and complicate the

adversary’s targeting cycle, while maintaining the ability to mass effects and impose cost upon

the enemy in time and material.

• Widely distributed operations may create competition for limited shipping, connectors, tactical

airlift, and assault support assets across the task force. Yet forces conducting EABO must rely on

these for movement to the area of operations (AO) and maneuver within EABs. When movement

means are insufficient to support planned operations and additional means cannot be made

available, commanders must reevaluate and modify the scheme of maneuver (SOM).

• Littoral forces must carefully manage their signatures across spectrums and domains to enhance

survivability while conducting localized movement and maneuver. Where possible, HN support

may enable forces to reduce their signatures.

• Forces conducting EABO must be able to reliably communicate with higher echelons for

information and intelligence despite enemy efforts to degrade or deny use of the EMS or in a

degraded environment.

Also inherent to EABO and the maritime domain is the imperative to sustain the force, often from the sea.

How the force is sustained inside the WEZ will require foresight and non-traditional methods, including

forward provisioning, which is described in chapter 6. In many cases, forces must rely on globally

positioned materiel, afloat and ashore, emplaced during competition, in order to enable and sustain

operations until access to the joint logistics enterprise is established. This requirement, combined with

mobility limitations imposed by terrain and infrastructure, may guide the commander to more heavily

weight access to intermodal transfer points in positioning forces. Intermodal transfers represent periods

of vulnerability that require close coordination among forces. Reliance on sustainment afloat through

intermodal transfers may be a limiting factor for littoral force operations ashore. In some cases,

sustainment will need to be conducted by and through a HN’s military or civilian resources.

Prescribed conditions also influence and demand attention during planning for EABO in several ways.

These conditions are usually, but not exclusively, prescribed by the establishing authority in the initiating

directive in the form of constraints and restraints. First, the HN often imposes restrictions that limit the

commander’s freedom of action. For example, specific conditions may limit the allocation, employment,

and control of surface attack munitions. HN prescribed constraints and restraints will influence the

planning and operations of the littoral force in both competition and armed conflict.

Second, during planning for operations across the competition continuum, higher headquarters may

initially assign the littoral force multiple potential objectives, with the selection of a specific objective

2-3

delayed until just prior to execution. This requirement provides flexibility at the operational level by

exploiting the littoral force’s inherent mobility and flexibility. However, it complicates littoral force task

organization and ship-to-objective-area planning. Separate plans for separate objectives must be prepared

with normal attention to detail and, to the extent permitted by the various schemes of maneuver, must

provide for the employment of the same littoral forces in the same general configuration and order. The

planning challenge is similar to that faced by Marine Expeditionary Units (MEUs), which must be

configured and embarked to execute multiple missions. Littoral forces must be configured and embarked

so that they are capable of executing a variety of missions to achieve multiple objectives across the

competition continuum.

Finally, higher headquarters may set conditions for strict emissions control, which creates a unique

challenge during distributed operations. Given the character of EABO requiring extensive use of

communications and electronic equipment to coordinate, direct, and support execution of EABO, widely

dispersed EABs are potentially vulnerable to exploitation by adversary signal intelligence and

electromagnetic warfare (EW) efforts. Special attention is required to ensure effective signature

management (SIGMAN) and signal security during each phase, stage, and step of an operation.

2.4 PLANNING FRAMEWORK

Planning for EABO is built on the framework provided by the established military decision-making

model. It is guided by the tenets found in the Marine Corps Planning Process/Navy Planning Process:

top-down planning, single-battle concept, and integrated planning.

5

As with all planning, the enduring

requirement is both continual refinement and the iterative nature of the process, with emphasis on branch

plans and sequels. As stated in Marine Corps Planning Process, Marine Corps warfighting publication

(MCWP) 5-10, planning should not be simply a series of steps. The incorporation of feedback loops and

informed analysis is critical to allow the commander to function and thrive in an austere and dynamic

environment. The following focus areas are specifically highlighted due to the unique strains that EABO

will place on them.

Integration. Joint Maritime Operations, Joint Publication (JP) 3-32, outlines the importance of

integrating maritime planning and ensuring consistency with the Joint Planning Process.

6

When

conducting EABO, the need to function in a high-paced, resource-constrained environment adds

importance to taking every opportunity to promote an integrated use of resources and capabilities across

domains and through multiple echelons of command. The littoral force, operating in a mobile and

distributed manner, will often need to leverage joint, coalition, and HN capability. In addition to

integrating littoral force efforts with those of the greater joint force, the commander must seek these same

efficiencies and integrate the operations and capabilities of the littoral force across time, space, and

purpose.

Risk. Risk describes a situation involving exposure to danger or damage. Risk to force and risk to

mission are inherent in all military operations. The littoral force commander (LFC) must also understand

risk in terms of the opportunities that reside within the operating environment. Through understanding of

the battlespace and appropriate planning, the commander manages risk through sequencing, phasing, and

integration. Boldness is a key attribute in littoral operations.

5

Headquarters, US Marine Corps, Marine Corps Planning Process, MCWP 5-10 (Washington, DC: US Marine

Corps, 2020).

6

Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Maritime Operations, JP 3-32 (Washington, DC: US Department of Defense, 2018).

2-4

2.5 NAVAL COMMAND AND ORGANIZATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

2.5.1 Command Arrangements

Command arrangements include decisions made about how forces are task organized, what tasks each

formation is assigned, what AO they are responsible for, who commands the different formations, and the

command relationships among commanders. Naval command arrangements are based upon centralized

guidance, collaborative planning, and decentralized control and execution. “Unity of command facilitates

unity of effort. Unity of effort, the product of successful unified action, assures coordination and

cooperation among all forces toward a commonly recognized objective, although they are not necessarily

part of the same command structure.”

7

When possible, naval tactical organizations seek to achieve unity

of effort through unity of command.

Navy tactical forces provide operational commanders numerous capabilities through multi-mission

platforms. Marine tactical forces provide operational commanders capabilities that complement those of

Navy tactical forces and extend the reach of the fleet into both landward and seaward portions of the

littorals.

2.5.2 Task Organization of Fleet and Maritime Forces

Naval task forces are normally delegated the authority to plan and execute tactical missions on behalf of

the joint force maritime component commander (JFMCC), and they represent the highest echelon of task-

organized naval forces. The fleet commander normally task organizes assigned tactical forces—including

forces assigned to the FMF under the fleet commander’s operational or tactical control—into formations

with the capabilities to operate throughout all dimensions of the maritime domain to accomplish a given

mission or set of missions. These formations may remain at the fleet level or be scaled to provide the

right mix of capability and capacity through various combinations of task forces, task groups, task units,

or task elements.

2.5.3 Naval Task-Organization Hierarchy

Naval task organization typically involves a tailored hierarchy of task forces (TFs), task groups (TGs),

task units (TUs), and task elements (TEs), as depicted in figure 2-1.

7

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Maritime Operations at the Operational Level of War, NWP 3-32

(Washington, DC: US Navy, 2008). For thorough discussions of unity of command and unity of effort in addition to

Maritime Operations at the Operational Level of War, NWP 3-32, see Office of the Chief of Naval Operations,

Composite Warfare: Maritime Operations at the Tactical Level of War, NWP 3-56 (Washington, DC: US Navy,

2015), and JCS, Doctrine for the Armed Forces, JP 1.

Figure 2-1. Notional naval task organization

2-5

Three-Star/Three-Digit Task Forces. Navy numbered fleets and Marine expeditionary forces (MEFs) are

the largest TFs in the maritime component, normally two-digit TFs. When employed in naval operations

with multiple fleets or multinational partners, they are usually designated as three-digit TFs.

Navy Warfare Area and Functional Task Forces/Task Groups. Below each numbered fleet, subordinate

commands are divided by naval warfare areas and functional areas. Although each fleet is slightly

different in composition and organization, these are typically fleet battle forces, special warfare, maritime

patrol and reconnaissance, logistics, undersea forces, naval expeditionary combat forces, and amphibious

forces. These are identified as two-digit TFs in peacetime but may be re-designated as three-digit TGs for

operational employment.

Fleet Marine Forces Organized as Naval Task Forces and Task Groups. When a MEF is assigned to the

JFMCC to conduct EABO, major subordinate commands, such as the division, are normally designated as

three-digit TGs.

Multi-mission Task Groups. These TGs are the largest mobile naval formations and may include carrier

strike groups (CSGs), expeditionary strike groups (ESGs), surface action groups (SAGs), littoral combat

groups, and littoral combat forces.

Task Units. Task units typically consist of smaller groups of ships and other naval assets that serve a

functional purpose or are assigned a specific mission or limited range of missions in support of a multi-

mission task group, in support of the fleet, or in support of a specific joint force function such as ballistic

missile defense. Littoral forces will normally be task organized to conduct EABO as a TU and will

normally be composed of forces at the O-6 level of command. These littoral forces may be subordinate to

a multi-mission TG.

Task Elements. Task elements are often single ships. In situations involving a littoral force designated as

a TU, its TEs would constitute the littoral force’s smallest units of action.

2.6 FRAMEWORK FOR DECENTRALIZED EXECUTION

2.6.1 Mission Command and Control

The principles of maneuver warfare and mission command and control must permeate all actions of

littoral forces conducting EABO, from planning through execution. During planning, commanders aim to

create conditions during execution that enable subordinates to operate guided by the essential elements of

mission command and control: low-level initiative, commonly understood commander’s intent, mutual

trust, and implicit understanding and communications.

8

Planning for EABO avoids a high degree of

scripting and top-down direction, which usually aims to minimize uncertainties; rather, it must lead to

understanding of the mission, intent, and broad guidance, creating freedom of action and maximizing

opportunities for subordinates. Planning must be participatory, enabling leaders at every level within the

littoral force to engage in the planning process and not merely consume a finalized and overly prescriptive

directive. Given the anticipated OE, planning for EABO must ultimately foster a command and control

(C2) environment which enables commanders at every level of the littoral force to cope with uncertainty,

exercise initiative, generate tempo, and seize opportunities guided by mission and intent and bounded by

a limited set of operational parameters.

Littoral forces may conduct EABO as part of either standing or temporary task forces. Given the

anticipated OE, littoral forces are likely to find themselves dynamically re-tasked to support adjacent

units and execute operations based on direction from outside the immediate chain of command. Thus,

8

Headquarters, US Marine Corps, Command and Control, MCDP 6 (Washington, DC: US Marine Corps, 2018).

2-6

commanders must prepare their forces, at times, to respond to the control of external units that have been

delegated authority to accomplish functionally aligned missions. Composite warfare is one example of a

C2 construct that may enable operations within this fluid C2 environment. Operating within this

construct requires coordination, planning, and procedures distinct from those typically familiar to Marine

commanders and their staffs.

2.6.2 Composite Warfare

The commanders and staff of littoral forces must be thoroughly familiar with the contents of Composite

Warfare: Maritime Operations at the Tactical Level of War, Navy Warfare Publication (NWP) 3-56.

Composite warfare doctrine is a framework for command characterized by command by negation,

decentralized control and execution, and collaborative planning. Due to the widely distributed nature of

maritime combat, composite warfare employs command through preplanned actions to address threats by

delegating warfare functions to subordinate commanders. Subordinates take action immediately, guided

by the commander’s intent, keeping the commander informed of the actions they take. Just as Marine

commanders will communicate mission and tasks via operations orders updated by fragmentary order,

composite warfare commanders issue orders via operational tasking message (OPTASK) updated by daily

intentions message.

Key personnel within this construct include the officer in tactical command (OTC), composite warfare

commander (CWC), warfare commanders, functional group commanders, and coordinators, as depicted

below in figure 2-2. The OTC is the senior officer present eligible to assume command, and in

application is often the fleet commander. The OTC may retain the duties of the CWC but will often

assign these command functions to a subordinate. The OTC always retains responsibility for missions

and forces assigned.

9

9

OPNAV, Composite Warfare, NWP 3-56.

Figure 2-2. Notional composite warfare organization

(MIWC)

2-7

The CWC delegates assignments as warfare commanders to subordinates. Warfare commanders are

assigned duties of extended duration and broad situational applicability such as the air and missile defense

commander (AMDC), surface warfare commander, and information warfare commander. The assignment

of subordinate warfare commanders enables simultaneous offensive and defensive actions through

decentralized execution. NWP 3-56 provides detailed descriptions of these positions and their

responsibilities. The proposed expeditionary warfare commander (EXWC) is described in a draft Tactical

Memo on the composite warfare construct to support further wargaming and experimentation.

Littoral forces should anticipate employment in a manner similar to a multi-mission ship or group of

ships, extending the sensing range of the fleet and providing capabilities to warfare commanders in the

surface, subsurface, and air domains.

The CWC may form temporary or permanent functional groups within the overall organization.

Functional groups are subordinate to the CWC and are usually established to perform duties that are

generally more limited in scope and duration than those conducted by warfare commanders. In addition,

the duties of functional group commanders generally span assets normally assigned to more than one

warfare commander. The ballistic missile defense commander is an example of a functional group

commander that may be supported by littoral forces.

Finally, resource coordinators may be established to execute the policies of the CWC and respond to the

specific tasking of either warfare commanders or functional group commanders. Resource coordinators

are usually designated when specific resources impact more than one warfare commander. The air

resource element coordinator is an example of a coordinator who executes the policies of the CWC with

all providers of air resources.

2.6.3 Main Planning Considerations

The following planning considerations allow the LFC to design the littoral force appropriately to

accomplish assigned tasks.

Assessing Requirements and Task-Organizing EABs. Forces organized for EABO may be assigned a

single task, a few tasks, or many tasks depending on requirements of the mission. Once the requirements

of an EAB are established, the commander task organizes elements of the littoral force to accomplish the

mission. By designing a purpose-built task element consisting of a unit of action (typically a reinforced

platoon), supporting staff, and sustainment, the commander best supports mission requirements while

minimizing signature. These task elements do not exist as a permanent unit in force structure – they are

formed as needed. The littoral force’s units of action should be organized based upon the commander’s

analysis of mission requirements.

Warfighting Functions. The commander must conceptualize capabilities to execute operations in terms of

the warfighting functions. Considering the assigned tasks through the lens of the warfighting functions

encourages planning for the design and employment of forces in the most ideal posture to achieve desired

effects across the competition continuum.

Warfare Commander Requirements. The commander of littoral forces may be designated an EXWC. As

an EXWC, the LFC may be delegated authority and resources to accomplish missions assigned by the

CWC. Simultaneously, the EXWC would retain the requirement to support hierarchically adjacent

warfare commanders in support of their assigned missions within respective domains. The EXWC must

also be aware and capable of executing relevant preplanned responses as prescribed in the OPTASK.

2-8

Evaluating EAB Posture. The fundamentals of offensive and defensive planning provide useful

considerations for the commander to integrate into his/her planning model. These may include flexibility,

including the desire to maintain multiple courses of actions (COAs); mutual support, where the

relationship and positioning of units mitigate gaps that exist when units operate independent of each

other; and surprise, where the commander employs available capabilities to deceive the adversary and

manages the signature of his/her forces to present a desired posture.

Designating Critical Capabilities. Based on the mission and the commander’s assessment of the threat,

the commander must determine the critical capabilities of the littoral force. Some of these critical

capabilities may result from the littoral force’s role and functions within the composite warfare

organization and the demands of the various warfare commanders. The commander organizes the force to

fully capitalize on these capabilities and ensure responsiveness within composite warfare.

Identifying Gaps/Shortfalls. Throughout all phases of the planning process, gaps and shortfalls are

reevaluated and assessed in terms of risk to the force and risk to the mission. Based on risk

determination, gaps and shortfalls are communicated via the chain of command. This information may

cause assigned tasks to be modified, allocation of additional resources or modification of the force

posture.

Assigning Subordinate Missions. Having considered the requirements of the warfare commanders and

joint force, capabilities of the adversary, impacts of the local environment, and requirements to sustain the

force, the commander is prepared to organize the littoral force to conduct operations. The littoral force

commander assigns subordinate forces and missions and, perhaps most importantly, communicates the

capabilities of the task-organized force to the CWC and warfare commanders.

2.6.4 Planning Responsibilities

Commanders must understand the different levels of authority and the impact each has on the

commander’s ability to control assigned and attached forces. Commanders provide tactical direction and

guidance through a clear statement of intent. The nature and focus of planning varies by echelon, while

all actions are coordinated through the lens of single battle. To achieve unity of effort, commanders

ensure that (1) subordinates clearly understand the command authority they have been granted and (2) the

forces assigned understand what this authority allows.

Officer in Tactical Command. The OTC is the senior officer present eligible to assume command or the

officer to which the senior officer present has delegated tactical command. The OTC’s planning will

normally focus on power projection and sea-control operations.

Composite Warfare Commander. Appointed by the OTC, the CWC’s planning efforts will normally

focus on operations to counter threats to the force. The CWC appoints warfare commanders who in turn

align resources to surveillance areas (SAs); classification, identification, and engagement areas; and vital

areas

10

, which are discussed below in subsection 2.6.5.

Expeditionary Warfare Commander (proposed). The proposed EXWC is the senior commander of littoral

forces who is subordinate to the CWC for the execution of assigned missions. As a warfare commander,

the EXWC simultaneously possesses certain delegated authorities of the CWC, while also supporting

hierarchically adjacent warfare commanders in the execution of their assigned missions. Thus, the

EXWC’s planning efforts must address his/her own operational requirements, while also planning to

10

OPNAV, Composite Warfare, NWP 3-56.

2-9

support those of other warfare commanders. If the EXWC is assigned a littoral operations area (LOA),

11

this commander may also be assigned authorities of the littoral force commander, discussed in the next

paragraphs and therefore be responsible for several primary decisions during planning, which are

discussed below in subsection 2.6.5.

For the purposes of experimentation, this manual uses the general term LFC to describe the individual

who, regardless of the task organization or echelon, exercises command over all littoral forces conducting

EABO within an LOA. While not exhaustive, the following examples illustrate some possible

implementations:

• A naval O-6 task-unit commander, subordinate to a task group, may fulfill this role as the senior

commander of a littoral force.

• A naval O-8 task-group commander may fulfill this role, exercising command over littoral forces

within multiple LOAs.

The rationale for introducing the term LFC is twofold. First, during EABO an LFC may not operate

within the composite warfare construct and therefore not fulfill any composite warfare roles. Second, an

LFC operating within composite warfare may not be designated a warfare commander, function group

commander, or coordinator.

2.6.5 Organization of Battlespace

When employed in naval operations with multiple fleets or multinational partners, numbered fleet and

MEF commanders are designated as three-digit task forces by the JFMCC. A likely construct for naval-

force employment is that these three-digit task forces will be assigned AOs by the JFMCC, and each will

serve as OTC within the assigned AO. Task force commanders will organize and manage their

battlespace according to doctrinal maneuver control measures, fire support coordination measures

(FSCMs), waterspace management, and prevention of mutual interference.

When conducting EABO, task force commanders must take advantage of littoral terrain to integrate with

joint force operations and generate tempo in decision making and action against the adversary. Maneuver

in the littorals creates the possibility to extend the range of fleet sensors and shooters beyond the

classification, identification and engagement areas and SAs of traditional task groups. Accordingly, this

manual allows for task force commanders, and the task groups supporting them, to experiment with

appropriate naval command and control to best enable integrated, all-domain operations for modern naval

warfare. Task force commanders can employ littoral forces to conduct EABO at any echelon (TE, TU,

TG, and TF), as required by mission and geography. Task group commanders may be designated as

CWCs, and littoral forces designated as task units and below may operate under task group command

using composite warfare. Marine Corps units in those formations must be able to integrate seamlessly

with the CWC structure. Task force commanders may also integrate littoral forces conducting EABO

with adjacent task groups using other battlespace management constructs.

For purposes of simplicity, these various options can be compressed into three general types of command

arrangements for experimentation, summarized as follows:

• Littoral forces operate under the CWC of an afloat Navy task group

• Littoral forces operate as their own task group using Marine air-ground task force (MAGTF) C2

• Littoral forces operate as their own task group using composite warfare

11

Discussed in greater detail in subsection 2.6.5, an LOA is a geographical area of sufficient size for conducting

necessary sea, air, and land operations in order to accomplish assigned mission(s) therein.

2-10

Figure 2-3 provides examples of a maritime AO integrating littoral forces with other forces of the fleet

operating in the air, sea, undersea, and in space and cyberspace.

Littoral Operations Area. Among the battlespace control measures the JFMCC and fleet commanders

may use, this manual proposes for experimentation two forms of a LOA within the maritime AO: the

LOA as battlespace and the LOA as a permissive control measure. See figure 2-4 below.

LOA as Battlespace. When the JFC appoints a JFMCC, the JFC will normally designate a maritime AO.

The JFMCC may then establish subordinate maneuver space for subordinate elements. The LOA

encompassing both landward and seaward littoral terrain may be assigned as subordinate maneuver space.

The designation of the LOA as battlespace within the maritime AO is intended to ensure unity of effort

and the integration of resources under a fleet or JFMCC commander to accomplish assigned missions.

This could include controlling a maritime chokepoint or controlling portions of the littorals necessary to

support the fleet’s freedom of maneuver and operational design. The designation of the LOA as

battlespace assigned to one subordinate commander should not exclude other naval force actions within

the LOA such as transit or coordination of fires; these actions simply require the coordination and

approval of the commander within the LOA. The authority to designate the LOA within the maritime AO

may be retained at a level as high as the JFMCC.

LOA as a Control Measure. Within the established battlespace of the maritime AO and the subordinate

maneuver space, the LOA may be a control measure. As a control measure, it could be assigned by the

fleet commander to a subordinate commander for positioning of forces, or assigned by a CWC for the

EXWC for maneuver of expeditionary forces. This requires the integration of the CWC’s resources

across specified domains and within the limits of the LOA.

Figure 2-3. Littoral operations areas in the context of composite warfare

2-11

Considerations for LOA Planning and Development. The LOA is a multidomain control measure.

Within composite warfare, the LOA enables a commander designated as the EXWC employing littoral

forces to mass the combined resources of the CWC within the LOA. The CWC, appointed by the OTC,

may in turn appoint functional or subordinate warfare commanders. The EXWC, acting within the limits

of the LOA, is effectively a subordinate warfare commander responsible for integrating the resources of

the task group to achieve a specific outcome within the three-dimensional limits of the LOA.

Simultaneously, the EXWC remains responsive to the requirements of hierarchically adjacent warfare

commanders.

Within the LOA, each unit of action will be assigned a sector, which is an area designated by boundaries

within which the unit will operate and for which it is responsible. Units of action may also be assigned

engagement areas wherein the commander intends to contain and destroy an enemy force with the effects

of massed weapons and supporting systems. Forces assigned responsibility for engagement areas must

ensure that their internal fire support coordination measures support the requirements of the engagement

area.

Naval Battlespace Terminology Related to Afloat Formations. Three doctrinal terms associated with

battlespace constructs for operations of composite task organizations at sea, discussed below in further

detail, should also be understood by forces conducting EABO: surveillance area (SA); classification,

identification, and engagement area (CIEA); and vital area (VA). The CWC defines the task force’s

protected asset(s), and warfare commanders such as the sea combat commander (SCC) or AMDC define

the ranges associated with these battlespace constructs. Littoral forces must consider the requirements of

these battlespace constructs when positioning assets. Through experimentation, they must also explore

how landward forces might contribute to operations in the following areas defined within composite

warfare.

• S

urveillance Area. In surface warfare, a SA encompasses the OE that extends out to a range that

equals the force’s ability to conduct a systematic observation of a surface area to detect vessels of

Figure 2-4. Notional littoral operations area

2-12

military concern. The dimensions of the SA are a function of strike group surveillance

capabilities, sensors, and available theater and national assets.

12

• Classification, Identification, and Engagement Area. In maritime operations, a CIEA describes

the area within the SA and surrounding the VA(s) in which all objects detected are classified,

identified, and monitored. Within the CIEA, friendly forces maintain the capability to escort,

cover, or engage. The goal is not to destroy all contacts in the CIEA, but rather to make decisions

about actions necessary to mitigate the risk each contact poses. The CIEA typically extends from

the outer edge of the VA to the outer edge of where surface forces effectively monitor the OE. It

is a function of friendly force assets/capabilities and reaction time, threat speed, the warfare

commander’s desired decision time, and the size of the VA.

13

• Vital Area. A VA is a designated area or installation defended by air defense units. The VA

typically extends from the center of a defended asset to a distance equal to or greater than the

expected threat’s weapons release range. The intent is to engage threats prior to them breaching

the perimeter of the VA. The size of the VA is a function of the anticipated threat. In some

operating environments, such as the littorals, engaging threats prior to their breaching the VA is

not possible because operations are required within the weapons-release range of potential

threats. Preplanned responses shall include measures for engaging contacts initially detected

within, rather than outside, the VA.

Note: Potential exists for multiple organizations to conduct operations within a JFMCC’s AO. To ensure

unity of command and unity of effort, the JFMCC should ensure common processes and procedures exist

for the shifting of tracking across organizational seams.

14

Control Measures. The Naval Service is used to coordinating operations through their battlespace in three

dimensions. Control measures coordinating maneuver, fires, and airspace are critical for managing the

battle, providing operational flexibility and minimizing risk. The littoral force will plan and coordinate

control measures that cover all domains and enable integration with the larger joint fight. This system

must be clearly communicated at all times but also include processes to allow for responsive action in a

communication degraded/denied environment.

Existing doctrinal terms, symbols, and naming conventions will be used, as appropriate, when designating

control measures for surface and air movement and maneuver—whether seaward or landward—in

conjunction with EABO.

Littoral Transition Point (LTP). These are locations where forces conducting surface littoral maneuver

will shift between waterborne and overland movement in either direction. Normally, forces conducting

EABO will preplan multiple LTPs and avoid repeated use of the same point in order to reduce the

likelihood of detection and targeting. Arabic numerals will be used to number LTPs.

2.7 COMMAND AND CONTROL

After receipt of the initiating directive, mission analysis, and task organization of forces, the commander

must prepare the staff and subordinate elements to function within the assigned command structure. It

should be expected that command relationships will remain dynamic and may rapidly shift based on

operational requirements. Commanders must ensure that their staffs are prepared to execute transitions

between command structures. For example, the commander and staff may initially be subordinate to a

12

OPNAV, Composite Warfare, NWP 3-56.

13

OPNAV, Composite Warfare, NWP 3-56.

14

OPNAV, Composite Warfare, NWP 3-56.

2-13