CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU | JANUARY 2022

Annual report of credit and

consumer reporting

complaints

An analysis of complaint responses by

Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion

Table of Contents

Table of Contents .............................................................................................................2

Executive Summary .........................................................................................................3

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................5

2. Background ..............................................................................................................10

2.1 Credit reporting overview........................................................................ 10

2.2 Dispute process .........................................................................................12

2.3 CFPB complaint process.......................................................................... 14

2.4 Credit monitoring, credit repair, and credit education .......................... 16

3. Complaint data .........................................................................................................21

3.1 Factors underlying complaint volume increases .................................... 24

3.2 Consumer issues and harms.................................................................... 29

4. Fair Credit Reporting Act Section 611(e) .............................................................39

4.1 The Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act ..................................... 39

4.2 Transmission of complaints and data collection ....................................40

5. NCRA complaint response analysis .....................................................................44

5.1 Previous dispute attempts ....................................................................... 45

5.2 NCRAs’ changes to complaint responses ................................................46

6. Conclusion................................................................................................................55

3 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Executive Summary

▪ Pursuant to Section 611(e)(5) of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), this report

summarizes information gathered by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)

regarding certain consumer complaints transmitted by the CFPB to the three largest

nationwide consumer reporting agencies (NCRAs)—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion.

▪ The CFPB historically has satisfied its annual reporting obligation by including information

gathered pursuant to FCRA Section 611(e) in its Consumer Response Annual Report. This

year, however, increased complaint volume about the NCRAs and the NCRAs’ concurrent

changes in response to those complaints led the CFPB to publish this independent report.

▪ From January 2020 to September 2021, the CFPB received more than 800,000 credit or

consumer reporting complaints. Of these complaints, more than 700,000 were submitted

about Equifax, Experian, or TransUnion. Complaints submitted about the NCRAs accounted

for more than 50% of all complaints received by the CFPB in 2020 and more than 60% in

2021. The CFPB’s analysis shows that consumers are submitting more complaints in each

complaint session and are increasingly returning to the CFPB’s complaint process.

▪ In their complaints to the CFPB, consumers describe harms stemming from their failed

attempts to correct incomplete and inaccurate information on their credit reports:

□ Consumers are caught in an automated system where they are unable to

have their problem addressed. Consumers described how they attempted to

dispute inaccurate information with the NCRAs but were unsuccessful. Attempts to

have their problems addressed timely appear especially important to consumers who

are making large financial transactions, such as buying a house, or applying for

housing or employment.

□ Consumers waste time, energy, and money to try to correct their reports.

Consumers described the burden associated with attempting to correct inaccurate

information, which can be compounded when they are managing other personal

issues. Some consumers reported discovering that debts (such as medical bills) had

been reported to their credit report without their knowledge. Consumers described

4 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

being exasperated by the dispute process and some consumers described paying bills

they did not think they owed because of concerns about the effect of the debt on their

credit report and credit score.

□ Consumers are caught between furnishers and the NCRAs. Consumers

described attempting to dispute incorrect information with both data furnishers and

the NCRAs. Consumers said that when furnishers and the NCRAs point fingers at

one another, they have limited avenues to resolve the problem, which can be

especially difficult for identity theft victims.

▪ Consumers have the right to dispute inaccurate and incomplete information on their credit

reports. Consumers also have the right to submit complaints to the CFPB. Most complaints

about the NCRAs received by the CFPB during 2020 and 2021 met the statutory criteria that

mandates the NCRAs review these complaints and respond to the CFPB.

▪ In 2020, Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion changed how they respond to complaints

transmitted to them by the CFPB. The CFPB’s analysis reveals that the NCRAs are closing

these complaints faster and with fewer instances of relief. In 2021, the NCRAs reported relief

in less than 2% of complaints down from nearly 25% complaints in 2019.

□ Pursuant to the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, the

CFPB’s complaint process allows for the submission of complaints by consumers’

third-party representatives. The CFPB expects the NCRAs to respond to complaints,

including complaints where they have an obligation to do so under FCRA Section

611(e), when submitted by consumers and representatives acting on their behalf.

□ The NCRAs ignore this obligation and, instead, do not respond when they suspect

that a third party was involved in the submission of the complaint. The NCRAs rely

on speculative criteria in reaching these decisions.

□ The NCRAs’ actions leave many consumers without a response to the issues they

raised in their complaints.

▪ The FCRA requires the NCRAs to conduct a review of certain complaints sent to them by the

CFPB and to report their determinations and actions to the CFPB. The NCRAs’ responses to

these complaints raise serious questions about whether they are unable—or unwilling—to

comply with the law.

5 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

1. Introduction

Credit reports

1

play an important role in the lives of consumers. Lenders often rely on these

reports when determining whether to approve loans and what terms to offer. Landlords may

review reports to decide whether to rent housing to prospective tenants. Employers may check

reports as part of the job application process. Given the consequential decisions for which credit

reports are considered, it is imperative that the credit reporting system maintain and distribute

data that are accurate. Access to an effective and efficient dispute management and resolution

process is legally required and essential to maintain the accuracy of consumers’ data.

Complaints submitted to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) about inaccurate

information and the dispute process make up a significant share of all complaints received by

the CFPB, and the complaint process provides a key backstop to dispute channels available to

consumers.

2

There are several actors who make up the credit reporting system: furnishers provide

information about consumers to consumer reporting agencies that, in turn, compile

information and make it available to lenders and other users. Pivotal to this system are the three

largest nationwide consumer reporting agencies (NCRAs): Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion.

More than 200 million Americans have credit files and nearly 15,000 providers furnish

1

Credit reports, a popular term for consumer reports that typically contain information about credit accounts and

other trade lines as well as information from public records, are provided by the nationwide consumer reporting

agencies and other consumer reporting agencies to lenders and other users. See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau,

Key Dimensions and Processes in the U.S. Credit Reporting System (2012),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201212_cfpb_credit-reporting-white-paper.pdf. See also 15 U.S.C. § 1681a(d).

2

See Fed. Trade Comm’n., Report on Complaint Referral Program Pursuant to Section 611(e) of the Fair Credit

Reporting Act (Dec. 2008), https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/section-611e-fair-credit-

reporting-act-federal-trade-commission-program-referring-consumer/p044807fcracmpt.pdf (“The [611(e)] program

was intended to enable consumers to obtain a second review of their complaints when they remain dissatisfied after

having completed the dispute process with the CRAs … .”).

6 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

information about consumers to the NCRAs.

3

Thus, the NCRAs’ actions—and inactions—have

large implications for consumers’ financial well-being and the economy more broadly.

4

The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) imposes various requirements on certain entities that

regularly compile and disseminate personal information about individual consumers.

5

The

CFPB and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) are the federal agencies with the principal

responsibility for enforcing the FCRA.

6

In addition to its enforcement authority, the CFPB has

rule writing authority under the FCRA, as well as supervisory authority over many of the key

institutions in the consumer reporting system. The CFPB is also tasked with compiling and

transmitting to the NCRAs certain complaints from consumers about them.

7

The CFPB carries

out this responsibility through its consumer complaint process.

8

3

See, e.g., Equifax, Equifax Investor Day (2021) at 70,

https://d1io3yog0oux5.cloudfront.net/_43f211346c1e89c67b4b544fb8ae253f/equifax/db/1987/19204/pdf/EFX+20

21+Investor+Day+Presentation+.pdf (more than 220 million consumers); Experian, Frequently Asked Questions on

Credit Reports, https://www.experian.com/ourcommitment/credit-report-faqs (more than 220 million consumers)

(last visited Dec. 4, 2021); TransUnion, Customer Credit Reporting,

https://www.transunion.com/solution/customer-credit-check (more than 200 million files) (last visited Dec. 4,

2021); Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau and Fed. Trade Comm’n., Accuracy in Consumer Reporting Part I,

https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/videos/accuracy-consumer-reporting-workshop-session-

1/ftc_accuracy_in_consumer_reporting_workshop_transcript_segment_1_12-10-19.pdf (“right now, we have a very

diffused furnisher population, about 14,000 to 15,000 furnishers”). See also Kenneth Brevoort, Phillip Grimm &

Michelle Kambara, Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Data Point: Credit Invisibles (May 2015),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf (CFPB research estimating that

188.6 million Americans have credit records at one of the NCRAs that could be scored and an additional 19.4 million

Americans have credit records that cannot be scored.).

4

See, e.g., House Financial Services Comm., Oversight and Investigations Subcomm., Consumer Credit Reporting:

Assess Accuracy and Compliance, 117th Cong. (May 26, 2021) (“House Hearing on Consumer Credit Reporting”)

(opening statement of Rep. Green, “Whether in assessing credit, employment, housing, insurance or even utilities, the

information provided by the major NCRAs has the power to either open or foreclose a vast array of opportunities that

undergird economic security and social justice for consumers”; opening statement of Rep . Barr, “The allocation of

credit is the lifeblood of the American economy, lenders, insurers and other financial firms rely on accurate credit

reports to reflect the potential risk of a customer.”).

5

15 U.S.C. § 1681 et seq.

6

See Senate Comm. on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, An Overview of the Credit Bureaus and the Fair Credit

Reporting Act, 115th Cong. (July 12, 2018) (S. HRG. 115-361), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-

115shrg32483/pdf/CHRG-115shrg32483.pdf (“An Overview of the Credit Bureaus”).

7

15 U.S.C. § 1681i(e)(1).

8

See discussion infra Section 2.3. See also Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Learn how the complaint process works,

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/complaint/process/.

7 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Reporting requirement and scope

Under the FCRA, the CFPB must submit an annual report to Congress regarding information

gathered by the CFPB about certain complaints

9

it transmits to the NCRAs.

10

In prior years, the

CFPB met this reporting requirement by including additional company-level, summary

information in the Consumer Response Annual Report.

11

In 2020, however, significant changes

in complaint volume and the quality of responses provided by the three largest NCRAs led the

CFPB to publish this stand-alone report.

12

In addition to meeting the FCRA reporting requirement, this report uses consumer complaint

information to provide the public with important context about the consumer reporting

marketplace and to provide policymakers with timely information, context, and analysis as they

deliberate various legislative proposals that would affect the credit reporting system.

13

This report proceeds in the following sections. Section 2 begins by providing an overview of the

credit reporting system, including the dispute process, the CFPB complaint process, and the

participation of other actors. Section 3 discusses consumer complaints to the CFPB and the

issues consumers experience when reviewing and attempting to correct their credit reports.

Section 4 traces the evolution of the FCRA 611(e) process since it became law in 2003. Section 5

provides information required by FCRA Section 611(e)(5), including observed complaint

response patterns and other information captured by the CFPB’s consumer complaint process.

Finally, Section 6 concludes this report.

Data sources

The data used in this report comes from two primary sources. The first is CFPB complaint data

collected during the consumer complaint process. The consumer complaint process, which is

described more fully in Section 2.3, collects information from both consumers and companies.

9

See discussion of covered complaints infra Section 4.1.

10

15 U.S.C. § 1681i(e)(5).

11

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Consumer Response Annual Report (Mar. 2020),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-response-annual-report_2019.pdf.

12

See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Consumer Response Annual Report (Mar. 2021) at 25,

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_2020-consumer-response-annual-report_03-2021.pdf (“Due

in part to the increase in complaint volume, the Bureau will issue a separate report later this year to provide a more

robust analysis of these complaints and responses.”).

13

See, e.g., Protecting Consumer Access to Credit Act, H.R. 1645, 117

th

Congress (2021); Comprehensive Credit

Reporting Enhancement, Disclosure, Innovation, and Transparency Act of 2021, H.R. 4120, 117

th

Congress (2021);

Medical Debt Relief Act of 2021, S.214, 117

th

Congress (2021); Consumer Credit Control Act of 2021, S.1343, 117

th

Congress (2021).

8 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

The CFPB makes a subset of this data publicly available in the Consumer Complaint Database.

14

This report primarily focuses on complaint data from January 2020 to September 2021;

however, data going back to 2018 is included to provide additional context.

15

From January

2020 to September 2021, the CFPB received more than 800,000 credit or consumer reporting

complaints. Of these complaints, more than 700,000 were submitted about Equifax, Experian,

or TransUnion.

The second data source is information gathered from several dozen informal interviews with

consumers who submitted complaints to the CFPB. The CFPB conducted these interviews to

gain a more complete understanding of consumers’ experiences with the CFPB’s consumer

complaint process.

16

Additionally, the CFPB spoke with non-profit credit counselors and the

Consumer Data Industry Association (CDIA), an international trade association representing

consumer data companies. These conversations have informed this report.

Terminology

The FCRA sets forth definitions and rules of construction of many key terms.

17

The CFPB is

providing this glossary to aid comprehension of this report only.

18

For the purposes of this

report, the CFPB uses the following terms:

▪ Consumer complaint: submissions to the CFPB that express dissatisfaction with, or

communicate suspicion of wrongful conduct by, an identifiable entity related to a

consumer’s personal experience with a financial product or service. Section 2.3 discusses

the complaint process in more detail.

▪ Consumer reporting agency (CRA): a company that assembles or evaluates information

on consumers and sells information in the form of consumer reports.

14

See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Consumer Complaint Database , https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-

research/consumer-complaints/. See also Disclosure of Consumer Complaint Narrative Data, 80 FR 15572 (Mar. 24,

2015), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2015/03/24/2015-06722/disclosure-of-consumer-complaint-

narrative-data.

15

This report fulfills the CFPB’s reporting requirement for complaints receiv ed from January to December 2020.

Complaints received before and after this reporting period are included for context.

16

These interviews are a valuable way to better understand the lived experiences of consumers who used the CFPB

complaint process; however, they are not intended to give the CFPB statistically significant data that can be

generalized to all consumers.

17

See 15 U.S.C. § 1681a.

18

The terms defined in this glossary are intended to enhance the readability for the audience, rather than to reflect a

legal interpretation by the CFPB.

9 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

▪ Nationwide consumer reporting agency (NCRA): a consumer reporting agency that

compiles and maintains files on consumers on a nationwide basis regarding a

consumer’s credit worthiness, credit standing, or credit capacity. In this report, the CFPB

uses the term NCRAs to refer to Equifax, Experian, or TransUnion.

▪ Covered complaints: complaints submitted to the CFPB about the NCRAs concerning

incomplete or inaccurate information where the consumer also appears to have disputed

the completeness or accuracy with the NCRA. The FCRA requires the NCRAs to subject

these complaints to additional review when the CFPB transmits the complaints to the

NCRAs.

19

Section 5 analyzes these complaints.

▪ Credit report: a consumer report provided by a NCRA to a user (such as a lender or debt

collector) that typically contains information such as the payment history and status of

credit and other accounts.

▪ Credit file or consumer file: the information about a consumer that is contained in a

CRA’s database. The term file, when used in connection with information on any

consumer, means all the information on that consumer recorded and retained by a CRA

regardless of how that information is stored.

▪ Dispute: the FCRA requires CRAs and furnishers to reinvestigate information contained

in a consumer’s credit file when the consumer disputes the accuracy or completeness of

that information. Consumers can dispute an item of information through a CRA (indirect

disputes), through the furnisher who provided the disputed information (direct

disputes), or both. Section 2.2 summarizes the dispute process.

▪ Furnisher: an entity that furnishes information relating to consumers to one or more

CRAs for inclusion in a consumer report.

▪ Trade line: information furnished by a creditor to a CRA that reflects the consumer’s

account status and activity, such as balance owed and payment history.

19

This additional review is detailed at FCRA Section 611(e)(3), 15 U.S.C. § 1681i(e)(3).

10 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

2. Background

This section provides background on the credit reporting system, focusing on the parts of the

system that interact with the CFPB’s complaint process. It discusses, in turn, the dispute process

(Section 2.2), the complaint process and its relationship to the dispute process (Section 2.3), and

actors that may play a role in consumers’ efforts to monitor their credit reports and attempt to

improve their credit standing (Section 2.4). Specifically, Section 2.4 addresses credit repair

organizations and emerging forms of credit education.

2.1 Credit reporting overview

The basic structure and operation of the credit reporting system is largely unchanged over the

last several decades.

20

CRAs assemble or evaluate consumer information from lenders and other

data furnishers and from public record providers to produce consumer reports and credit scores

that users rely on to make decisions.

The data standards that govern these data exchanges have evolved. The Metro 2 Format

21

, a

system of shorthand codes and fields to report trade lines, has now fully supplanted the Metro 1

Format.

22

But credit reports are still made up of some or all of the following components:

20

See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, supra note 1.

21

The credit industry’s trade association, the Consumer Data Industry Association, created the Metro 2 Format. It is a

standardized electronic data reporting format used by data furnishers to furnish consumer credit account data. See

generally Consumer Data Industry Ass’n., Metro 2® Format for Credit Reporting,

https://www.cdiaonline.org/resources/furnishers-of-data-overview/metro2-information/. See also Chi Chi Wu and

Richard Rubin, National Consumer Law Center, The Latest on Metro 2: A Key Determinant As to What Goes Into

Consumer Reports (Oct. 2018), https://library.nclc.org/latest-metro-2-key-determinant-what-goes-consumer-

reports (“Metro 2 is considered the standard format for the credit reporting industry and is essentially ubiquitous. It

has been designed so that information vital to the preparation of accurate consumer reports is identified and defined

in a manner to facilitate the routine provision of accurate and compl ete information.”).

22

Following a settlement with the New York Attorney General, the NCRAs stopped accepting data in the older Metro

1 format in 2015. See Settlement Agreement, In the Matter of the Investigation by the Attorney General of the State of

11 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

▪ Personal information: identifying information of the consumer with whom the credit file

is associated, such as the individual’s name, other names previously used, and current

and former addresses.

▪ Trade line information: accounts in the consumer’s name reported by creditors.

Creditors generally furnish the type of credit, credit limit or loan amount, account

balance, account payment history including the timeliness of payments (i.e., the payment

grid), whether the account status is current, delinquent or in collection, and the dates the

account was opened or closed.

▪ Public record information: public record data of a financial nature, such as consumer

bankruptcies.

▪ Collections: third-party collection items, reported by debt buyers or debt collection

agencies.

▪ Inquiry: request by a company to view a credit file.

23

The FCRA is concerned with ensuring that the various parties in the credit reporting system take

steps to ensure the data that flows through the system is accurate and is used only for

permissible purposes.

24

When preparing consumer reports, for example, CRAs must employ

reasonable procedures to “assure maximum possible accuracy” of the information concerning

the individual about whom the report relates.

25

The FCRA and Regulation V also set forth

requirements for furnishers concerning the accuracy and integrity of data furnished.

26

New York, of Experian Info. Sol., Inc., Equifax Info. Serv. L.L.C., and TransUnion L.L.C. (Mar. 8, 2015) ,

https://ag.ny.gov/pdfs/CRA%20Agreement%20Fully%20Executed%203.8.15.pdf. The requirement to retire the

Metro 1 Format was also included shortly thereafter in an Assurance of Voluntary Compliance entered into by the

NCRAs with Attorneys General from 31 states. See Assurance of Voluntary Compliance, In the Matter of Equifax Info.

Serv. L.L.C., Experian Info. Sol., Inc., and TransUnion L.L.C. (May 20, 2015),

https://www.ohioattorneygeneral.gov/Files/Briefing-Room/News-Releases/Consumer-Protection/2015-05-20-

CRAs-AVC.aspx.

23

See generally Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, What is a credit report?, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-

cfpb/what-is-a-credit-report-en-309/ (last updated Sep. 1, 2020). See also Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, What's a

credit inquiry?, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/whats-a-credit-inquiry-en-1317/ (last updated Sep. 4,

2020).

24

15 U.S.C. §§ 1681 and 1681b.

25

15 U.S.C. § 1681e(b). See also Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, CFPB Supervision and Examination Manual,

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-reporting-larger-participants_procedures_2020-

02.pdf.

26

15 U.S.C. § 1681s-2. See also Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Supervisory Highlights Consumer Reporting Special

Edition (Mar. 2017), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201703_cfpb_Supervisory-Highlights-

12 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Furnishers and CRAs have additional dispute handling responsibilities. When consumers

believe there is inaccurate information in their credit report, the FCRA enables consumers to

dispute the information. Consumers may dispute information with the data furnisher (e.g., a

lender or servicer), one or more CRAs, or both the furnisher and CRAs (Section 2.2). Consumers

may also submit complaints to the CFPB (Section 2.3).

2.2 Dispute process

The structure of the FCRA creates interrelated legal standards and requirements to support the

goal of accurate credit reporting.

27

The FCRA provides consumers with dispute rights and

imposes obligations on both the NCRAs and furnishers to ensure that potential errors are

investigated and corrected promptly.

28

CRAs must satisfy legal requirements when information is disputed. Under Section 611 of the

FCRA, if a consumer disputes with the CRA the completeness or accuracy of an item of

information, the CRA has an obligation to conduct a reasonable reinvestigation.

29

There are

specific timelines, notification requirements, and actions a CRA must follow when conducting a

reasonable reinvestigation.

30

A CRA is not required to investigate a dispute if the CRA has

reasonably determined that the dispute is frivolous or irrelevant, but must notify the consumer

of its determination.

31

When a consumer disputes a trade line to the NCRAs, the dispute is often routed through the

Online Solution for Complete and Accurate Reporting (e-OSCAR), a system used by the NCRAs

to create and respond to consumer credit history disputes with furnishers.

32

The NCRAs

Consumer-Reporting-Special-Edition.pdf; CFPB v. Fair Collections & Outsourcing, Inc., No. 8:19-cv-02817-GJH (D.

Md. Sept. 16, 2021), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_fco_proposed_stipulated-jdmt-and-

order_2021-08.pdf (CFPB enforcement action against a furnisher of information to consumer reporting agencies for

failing to maintain reasonable policies and procedures regarding the accuracy and integrity of the information it

furnishes, including the handling of consumer disputes, failing to conduct reasonable investigations of certain

consumer disputes, and failing to cease furnishing information that was alleged to have been the result of identity

theft before it made any determination whether the information was accurate.).

27

See generally, An Overview of the Credit Bureaus, supra note 6.

28

15 U.S.C. § 1681i(a)(1)(A) and 12 C.F.R. § 1022.43(a).

29

15 U.S.C. § 1681i(a)(1)(A).

30

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Supervisory Highlights Consumer Reporting Special Edition (Dec. 2019) at

Section 3.4, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_supervisory-highlights_issue-20_122019.pdf.

31

15 U.S.C. § 1681i(a)(3)(A)-(C).

32

See e-OSCAR, About e-OSCAR, https://www.e-oscar.org/getting-started/about-us.

13 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

transmit an Automated Credit Dispute Verification (ACDV) that includes a dispute code,

narrative text, and since 2013, supporting documents provided by consumers.

33

Furnishers have independent obligations under the FCRA. Furnishers have specific timelines,

notification requirements, and actions they must follow when conducting an investigation.

34

Similar to CRAs, a furnisher is not required to investigate a direct dispute if the furnisher has

reasonably determined that the dispute is frivolous or irrelevant, but must notify the consumer

of its determination.

35

Consumers also play a vital role in promoting accurate reports. By disputing inaccurate

information—described by some consumers as a time-consuming and difficult process (Section

3.2)—consumers provide information that can be used by CRAs to evaluate whether furnishers

and other data sources provide reliable, verifiable information.

36

CRAs can also use consumer

disputes to assess their matching algorithms and other practices that may be introducing

inaccuracies. The CFPB has previously emphasized the importance of CRAs using disputes to

assess furnisher data quality. For example, as discussed in a recent edition of Supervisory

Highlights, the CFPB directed CRAs to revise their accuracy procedures to identify and take

corrective action regarding data from furnishers whose dispute response behavior indicates the

furnisher is not a source of reliable, verifiable information about consumers.

37

Consumers may

also dispute information that results from identity theft. The FCRA places additional

requirements on both CRAs and furnishers for consumer claims that disputed information is the

result of identity theft.

38

33

See, e.g., Chi Chi Wu, Michael Best, & Sarah Bolling Mancini, National Consumer Law Center, Automated Injustice

Redux at 9 (Feb. 2019), https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/credit_reports/automated-injustice-redux.pdf.

34

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, supra note 26 at Section 3. See also Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, CFPB

Bulletin 2013-09 (Sept. 9, 2013), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201309_cfpb_bulletin_furnishers.pdf

(discussing a furnisher’s obligation to review all relevant information received from a CRA in connection with a

consumer dispute); Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, CFPB Bulletin 2014-01 (Feb. 27, 2014),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201402_cfpb_bulletin_fair-credit-reporting-act.pdf (discussing a furnisher’s

obligation to investigate disputed information in a consumer credit report and provide notice of inaccurate

information to the CRAs).

35

15 U.S.C. § 1681s-2(a)(8)(F) and 12 CFR § 1022.43(f)(1)-(2).

36

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, supra note 26 at Section 2 (discussing data furnishing and furnisher

oversight).

37

See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Supervisory Highlights: Issue 24, Summer 2021 (Jun. 2021),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_supervisory-highlights_issue-24_2021-06.pdf.

38

15 U.S.C. § 1681c-2; 15 U.S.C. § 1681s-2(a)(6). See also CFPB v. Fair Collections & Outsourcing, Inc., No. 8:19-cv-

02817-GJH (D. Md. Sept. 16, 2021), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_fco_proposed_stipulated-

jdmt-and-order_2021-08.pdf (CFPB enforcement action against a furnisher of information to consumer reporting

agencies for failing to maintain reasonable policies and procedures regarding the accuracy and integrity of the

14 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

2.3 CFPB complaint process

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) directs the

CFPB to collect, investigate, and respond to consumer complaints.

39

The Dodd-Frank Act

requires the CFPB to establish reasonable procedures to provide consumers

40

with a timely

written response to complaints

41

concerning a covered person.

42

The CFPB accepts complaints about consumer financial products or services through its website,

by referral from the White House, congressional offices, other federal and state agencies, and by

telephone and mail. When consumers submit complaints through the CFPB website, the online

complaint form guides them through a five-step process:

1. Consumers first select the consumer financial product or service with which they have a

problem or issue. Within the credit or consumer reporting product category, consumers

can further select the type of credit reporting product (e.g., credit report and other

personal consumer report, such as background checks and employment screening).

2. Next, consumers identify the issue that best describes the problem they experienced. For

credit or consumer reporting complaints, options include: Credit monitoring or identity

theft protection services; Improper use of your report; Incorrect information on your

report; Problem with a credit reporting company’s investigation into an existing

problem; Problem with fraud alerts or security freezes; and Unable to get your credit

report or credit score. Consumers are also asked whether they have attempted to fix the

problem with the company.

3. Then, the complaint form prompts consumers to describe what happened and their

desired resolution using free-form text fields. Consumers are invited to attach relevant

documentation and can consent to have their complaint narrative published in the public

Consumer Complaint Database.

information it furnishes, including the handling of consumer disputes, failing to conduct reasonable investigations of

certain consumer disputes, and failing to cease furnishing information that was alleged to have b een the result of

identity theft before it made any determination whether the information was accurate.).

39

12 U.S.C. § 5511(c)(2).

40

12 U.S.C. § 5481(4) (“The term ‘consumer’ means an individual or an agent, trustee, or representative acting on

behalf of an individual.”).

41

See Terminology supra Section 1.

42

12 U.S.C. § 5534(a). See also 12 U.S.C. § 5481(6) (The term “covered person” means any person that engages in

offering or providing a consumer financial product or service and any affiliate if such affiliate acts as a service

provider to such person).

15 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

4. After that, consumers identify the company to which they want to direct their complaint.

Unlike most other products and services, a consumer’s problem with a credit or

consumer report may prompt them to submit multiple complaints—e.g., one about the

data furnisher and one about the CRA. The complaint form reflects this market feature.

When selecting the credit or consumer reporting product category, consumers can

choose to name additional companies in a single complaint session.

43

5. Finally, the complaint form requires users to identify whether they are submitting the

complaint for themselves or on behalf of someone else.

44

Consumers who submit

complaints on their own behalf are required to provide their contact information.

45

Users

submitting complaints on behalf of someone else are required to provide their contact

information, as well as the information of the person on whose behalf they are acting.

The complaint form also requires users to affirm that the information provided in their

complaint is true to the best of their knowledge and belief.

46

The CFPB routes the complaint directly to the company or companies identified by the

consumer for review and response. Where appropriate, complaints are routed to other federal

agencies.

47

Companies are expected to review the information provided in the complaint,

communicate with the consumer as needed, determine what action to take in response, and

provide a written response to the CFPB and the consumer.

Companies report back to the consumer and the CFPB in writing via a secure Company Portal.

Companies choose a closure category that best describes their response. Category options

include Closed with monetary relief, Closed with non-monetary relief, Closed with explanation,

and administrative options.

48

Finally, the CFPB invites the consumer to review and provide

feedback about the company’s response. Consumers can access their complaint online or may

43

In April 2017, in response to feedback from stakeholders and consumers, the CFPB made enhancements to

improve the user experience when submitting a complaint. Where consumers previously had to go through the entire

submission process separately for each company about which they were submitting a complaint, beginning in April

2017, consumers could use one submission process to submit complaints about up to four companies.

44

In May 2021, the CFPB made enhancements to this step of the complaint form. These changes emphasized that a

person submitting on behalf of someone else must identify themselves in the complaint submission. Additionally,

these changes required that users submitting on behalf of themselves provide an email address.

45

Consumers also have the option to provide limited demographic information , such as their age and servicemember

status. As of May 2021, users can also disclose their household size and combined annual household income.

46

The complaint form requires that users attest to their submission (“The information given is true to the best of my

knowledge and belief. I understand that the CFPB cannot act as my lawyer, a court of law, or a financial advisor.”).

47

For example, when the CFPB receives a complaint about a depository institution with $10 billion or less in assets or

a non-depository that does not offer a consumer financial product or service, it refers the complaint to the appropriate

prudential regulator or other regulatory agency.

48

See discussion of administrative responses infra Section 3.1

16 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

call the CFPB to receive status updates, provide additional information, and review responses

provided by the company.

Unique to the NCRAs, the CFPB asks additional questions for complaints in which the consumer

identified Incorrect information on your report or Problem with a credit reporting company's

investigation into an existing problem as their primary issue:

▪ Does your company have a record of the consumer disputing this issue in the past?

▪ Has a data furnisher reported any errors to your company regarding the information

disputed in the complaint?

If the response to either question is yes, the NCRAs are required to provide the CFPB with

details of any previous FCRA dispute or furnisher-reported error.

The CFPB uses information from its complaint process to inform its work, including its

supervisory, enforcement, rulemaking, and educational activities.

49

The CFPB publishes an

annual report to Congress about the complaints it receives, as well as other periodic reports.

50

The CFPB also makes complaint data publicly available in the Consumer Complaint Database.

51

2.4 Credit monitoring, credit repair, and

credit education

A variety of companies offer to mediate the relationship between consumers and their reports

and scores. Consumers frequently access their reports and scores through third parties,

including credit monitoring services, financial institutions and lenders, identity theft protection

49

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Having a problem with a financial product or service?,

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/complaint/ (“Complaints give us insights into problems people are experiencing

in the marketplace … .”). See also Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, supra note 25 (“An effective CMS should ensure that

an institution is responsive and responsible in handling consumer complaints and inquiries.”).

50

See, e.g., Consumer Response Annual Report (Mar. 2021), supra note 12. See also Lewis Kirvan and Robert Ha,

Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Consumer complaints throughout the credit life cycle, by demographic characteristics

(Sep. 2021), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-complaints-throughout-credit-life-

cycle_report_2021-09.pdf.

51

See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Consumer Complaint Database , https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-

research/consumer-complaints/.

17 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

services, and resellers.

52

The NCRAs also offer monitoring products (e.g., Experian’s Free Credit

Report and FICO Score app) and identity theft protection services (e.g., TransUnion’s

TrueIdentity).

Credit repair companies, credit clinics, and similar companies also interact with the credit

reporting system. Market research suggests that there are as many as 46,000 businesses that

offer credit repair services in the United States—the vast majority of which are sole

proprietorships.

53

These companies purport to help consumers identify and dispute information

on their credit reports, but many charge illegal fees, operate in bad faith, mislead consumers, or

are outright fraudulent.

54

Both the CFPB and the FTC have brought legal actions against credit

repair companies. For example, in recent years, the CFPB, the FTC, or both have brought

lawsuits against companies charging illegal fees to consumers in violation of the Telemarketing

52

See, e.g., Notice of a Public List of Companies Offering Existing Customers Free Access to a Credit Score , 81 FR

69046 (Oct. 5, 2016), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/05/2016-24014/notice-of-a-public-list-

of-companies-offering-existing-customers-free-access-to-a-credit-score (a Request for Information published by the

CFPB to inquire about which credit card providers offered access to a credit score; Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau,

Where to find free access to a credit score (Feb. 2017),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201702_cfpb_finding -free-access-to-credit-score_handout.pdf (a

list of financial institutions offering free access to credit scores). See also Press Release, Credit Karma, Credit Karma

Money launches bill features aimed at helping members improve their credit scores (Aug. 11, 2021),

https://www.creditk arma.com/about/releases/credit-karma-money-launches-bill-features-aimed-at-helping-

members-improve-their-credit-scores (“Credit Karma is a consumer technology company with more than 110 million

members in the United States, U.K. and Canada, including almost half of all U.S. millennials.”).

53

See, e.g., Arnez Rodriguez, IBISWorld, US Industry (Specialized) Report Od5741: Credit Repair Services (Feb.

2021), https://www.ibisworld.com/united-states/market-research-reports/credit-repair-services-industry/ (noting

that these companies frequently offer a variety of services, but that dispute processing is the most common service

provided). The CFPB recently brought a lawsuit alleging Credit Repair Cloud and its owner of providing assistance to

illegal credit-repair businesses. See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, CFPB Sues Software Company That Helps Credit-

Repair Businesses Charge Illegal Fees (Sep. 20, 2021), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-

us/newsroom/cfpb-sues-software-company-that-helps-credit-repair-businesses-charge-illegal-fees/.

54

See, e.g., Fed. Trade Comm’n., Telemarketing Sales Rule Record,

https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/rules/rulemaking-regulatory-reform-proceedings/telemarketing-sales-rule.

18 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Sales Rule

55

, misleading consumers in violation of the Telemarketing Sales Rule

56

, and violating

the Credit Repair Organizations Act, the Consumer Review Fairness Act, the Truth in Lending

Act, and the Electronic Fund Transfer Act.

57

Additionally, the CFPB and FTC have produced and

promoted resources intended to educate consumers about how to fix inaccuracies on their credit

reports, as well as the potential risks that arise from credit repair offers.

58

In Congressional testimony, the NCRAs identified credit repair companies as a major challenge

in their own dispute processes and in their handling of complaints.

59

In general, the NCRAs

55

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Files Suit Against Lexington Law,

PGX Holdings, and Related Entities (May 2, 2019), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/bureau-

files-suit-against-lexington-law-pgx-holdings-and-related-entities/ (lawsuit alleging the defendants violated the

Telemarketing Sales Rule (TSR) by requesting and receiving payment of prohibited upfront fees for their credit repair

services); Fed. Trade Comm’n., Grand Teton Professionals LLC, https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/cases-

proceedings/182-3168/grand-teton-professionals-llc (alleging credit repair scheme that charged illegal upfront fees

and falsely claimed to repair consumers’ credit violated the Telemarketing Sales Rule). See also Consumer Fin. Prot.

Bureau, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Commonwealth of Massachusetts File Suit Against Credit-

Repair Telemarketers (May 22, 2020), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-

commonwealth-massachusetts-file-suit-against-credit-repair-telemarketers/; Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, CFPB

Sues Software Company That Helps Credit-Repair Businesses Charge Illegal Fees (Sep. 20, 2021),

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-sues-software-company-that-helps-credit-repair-

businesses-charge-illegal-fees/.

56

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, CFPB Takes Action Against Company and its Owners and Executives for

Deceptive Debt-Relief and Credit-Repair Services (Jun. 29, 2021), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-

us/newsroom/cfpb-takes-action-against-company-and-its-owners-and-executives-for-deceptive-debt-relief-and-

credit-repair-services/. See also Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Sues Debt

Settlement Company FDATR, Inc., and Owners Dean Tucci and Kenneth Wayne Halverson (Nov. 20, 2020),

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-sues-debt-

settlement-company-fdatr-inc-and-owners-dean-tucci-and-kenneth-wayne-halverson/.

57

See, e.g., Fed. Trade Comm’n., FTC Stops Operators of Fake Credit Repair Scheme (Jun. 21, 2019),

https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2019/06/ftc-stops-operators-fake-credit-repair-scheme. See also

Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Returns More than $3.1 Million to Victims of Student Loan Debt Relief and Credit Repair

Scheme (Mar. 26, 2020), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2020/03/ftc-returns-more-31-million-

victims-student-loan-debt-relief.

58

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, A credit repair firm sent me an offer outlining their credit repair program.

Should I enroll? (Jun. 7, 2017), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/a-credit-repair-firm-sent-me-an-offer-

outlining-their-credit-repair-program-should-i-enroll-en-327/. See also Blog, Lisa Weintraub Schifferle, Fed. Trade

Comm’n., Credit repair: Fixing mistakes on your credit report (Jan. 16, 2020),

https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/blog/2020/01/credit-repair-fixing-mistakes-your-credit-report.

59

See Written Testimony of Beverly Anderson, Equifax, to House Financial Services Comm., Oversight and

Investigations Subcomm., Consumer Credit Reporting: Assess Accuracy and Compliance, 117th Cong. (May 26,

2021), https://www.congress.gov/117/meeting/house/112712/witnesses/HHRG-117-BA09-Wstate-AndersonB-

20210526.pdf; Written Testimony of Sandy Anderson, Experian, to House Financial Services Comm., Oversight and

Investigations Subcomm., Consumer Credit Reporting: Assess Accuracy and Compliance, 117th Cong. (May 26,

2021), https://www.congress.gov/117/meeting/house/112712/witnesses/HHRG-117-BA09-Wstate-AndersonS-

20210526.pdf; Written Testimony of John Danaher, TransUnion, to House Financial Services Comm., Oversight and

Investigations Subcomm., Consumer Credit Reporting: Assess Accuracy and Compliance, 117th Cong. (May 26,

2021), https://www.congress.gov/117/meeting/house/112712/witnesses/HHRG-117-BA09-Wstate-DanaherJ-

20210526-U1.pdf.

19 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

claim that credit repair companies submit large volumes of non-meritorious disputes.

60

They

argue that these disputes, if successful in the removal of accurate information, affect the ability

of lenders to effectively manage risk.

61

They also assert that the volume of disputes submitted by

credit repair organizations reduces resources available to appropriately handle legitimate

disputes.

62

Others, however, have suggested that the NCRAs’ actions facilitate the credit repair

industry.

63

Education providers also mediate the relationship between consumers and their reports and

scores. The CFPB, for example, as part of its statutory functions, provides consumers with

financial education, including answers to common consumer questions and how-to guides on

various topics in credit reporting.

64

Importantly, the CFPB—and the FTC—also provides sample

template letters for consumers to use when disputing information with the CRAs.

65

The CFPB

60

See, e.g., Written Testimony of Sandy Anderson, Experian supra note 59 at 2 (“We believe most of his [sic]

increase is due to third-party credit repair organizations that file dispute s on accurate but negative information to try

to game the system.”); Written Testimony of Beverly Anderson, Equifax supra note 59 at 4 (“The CFPB complaint

portal has been inundated with the rise of credit repair organizations’ submissions disputing accura te but adverse

information on consumers’ credit reports.”).

61

See, e.g., Written Testimony of Rebecca Kuehn, Hudson Cook, LLP on Behalf of the Consumer Data Industry

Association, to House Financial Services Comm., Oversight and Investigations Subcomm., Consumer Credit

Reporting: Assess Accuracy and Compliance, 117th Cong. (May 26, 2021),

https://www.congress.gov/117/meeting/house/112712/witnesses/HHRG-117-BA09-Wstate-KuehnR-20210526.pdf

("To the extent that these credit repair activities are successful in removing accurate information, they affect a

lender’s ability to appropriately assess the risk of their lending decisions, which in turn affects lending quality overall.

… Misuse of the dispute process is detrimental to consumers and the lenders that rely on accurate information to

appropriately assess risk.”). See also Written Testimony of Beverly Anderson, Equifax supra note 59 at 4 (“If a credit

repair organization is successful in clearing accurate, negative information from a report, that consumer may go on to

accumulate new credit obligations that the consumer is not able to afford, with lenders now blind to previous

obligations or payment behavior.”).

62

See, e.g., Written Testimony of Rebecca Kuehn, Hudson Cook, LLP on Behalf of the Consumer Data Industry

Association supra note 61 (“The time and resources expended investigating disputes made by credit repair companies

take away time and resources from focusing on legitimate disputes, which could otherwise be handled more

quickly.”).

63

See Written Testimony of Chi Chi Wu, National Consumer Law Center, to House Financial Services Comm.,

Oversight and Investigations Subcomm., Consumer Credit Reporting: Assess Accuracy and Compliance, 117th Cong.

(May 26, 2021), https://www.congress.gov/117/meeting/house/112712/witnesses/HHRG-117-BA09-Wstate-WuC-

20210526.pdf (“[T]here is some indication that, for all their complaints, the credit bureaus have entered into

agreements to cooperate with credit repair firms.”).

64

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Credit reports and scores, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/consumer-

tools/credit-reports-and-scores/. See also 12 U.S.C. § 5511(c)(1) (conducting financial education programs is one of

the primary functions of the CFPB).

65

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, How do I dispute an error on my credit report? (Oct. 19, 2021),

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/ask-cfpb/how-do-i-dispute-an-error-on-my-credit-report-en-314/. See also Fed.

Trade Comm’n., Sample Letter Disputing Errors on Credit Reports to the Business that Supplied the Information ,

https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/sample-letter-disputing-errors-credit-reports-business-supplied-

information.

20 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

provides these letters to help guide consumers to include information needed by the CRAs to

conduct a reasonable investigation.

New education providers and forms of educational content are also reaching consumers.

Support groups,

66

social media groups,

67

and influencers

68

publish and share content about

credit reports and scores. Many of these groups and influencers are marketing credit repair

goods (e.g., sample letters, kits, books, and seminars) and many are marketing credit repair

services.

As will be discussed in Sections 4 and 5, the NCRAs use similarity in narrative text to identify

what they suspect are complaints submitted by credit repair organizations. But with the growth

of educational content and providers—and the circulation of template language—it becomes

increasingly difficult to distinguish template language used by a credit repair organization from

template language used by a consumer (e.g., a consumer using a CFPB or FTC sample letter)

without contacting the consumer.

66

See, e.g., Meetup, Credit Repair, https://www.meetup.com/topics/credit-repair/ (more than 4,000 members

across 36 groups) (last visited Dec. 4, 2021).

67

See, e.g., Facebook, Credit Repair Cloud Community,

https://www.facebook.com/groups/creditrepaircloudcommunity/ (a group with more than 24,000 members) (last

visited Dec. 4, 2021). There are many similar groups in this topic area. See also Blog, Credit Karma, Gen Z turns to

TikTok and Instagram for financial advice and actually takes it, study finds (Jul. 13, 2021),

https://www.creditkarma.com/about/commentary/gen-z-turns-to-tiktok-and-instagram-for-financial-advice-and-

actually-takes-it-study-finds (“56% of Gen Z and millennials say they intentionally seek out information or advice

about personal finance online or through social media platforms”).

68

For example, YouTube lists over 1,800 channels that have posted videos with the hashtag #creditrepair. Several of

the videos have hundreds of thousands of views. See, e.g., YouTube, How To REMOVE Hard Inquiries From Credit

Report For FREE!, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qa4-obKYQGU (video with more than 600,000 views as of

Dec. 9, 2021).

21 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

3. Complaint data

In 2020, the CFPB received more than 319,000 credit or consumer reporting complaints.

69

That

number was quickly surpassed in 2021 with the CFPB receiving more than 500,000 credit or

consumer reporting complaints between January and September alone. Public discussion about

credit reporting complaints typically focuses on these record-breaking volumes.

70

This section

goes beyond those headline numbers to better contextualize the complaints data. To do so, this

section will discuss factors contributing to the increase in credit or consumer reporting

complaints over the past 20 months and the issues that consumers raise in their complaints.

Two details are worth noting at the outset. First, the volume of complaints received by the CFPB,

while large, is a fraction of the volume of disputes submitted to furnishers and CRAs annually.

Prior CFPB research estimated the NCRAs received millions of consumer contacts disputing the

completeness or accuracy of information on their credit reports.

71

Second, the credit reporting industry is the subject of a large number of complaints in part

because of its market structure. The industry has a large footprint—credit reports from the

NCRAs cover about 1.6 billion credit accounts per month on more than 200 million adults in the

United States.

72

Moreover, because trade line information is often furnished to multiple CRAs,

69

See Consumer Response Annual Report (Mar. 2021), supra note 12.

70

See, e.g., Ann Carrns, NEW YORK TIMES, More Consumers Complain About Errors on Their Credit Reports (Feb. 19,

2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/19/your-money/credit-report-errors.html (“Add this to the financial

fallout from the pandemic: More consumers are complaining about errors on their credit reports, and many are

frustrated when trying to fix the mistakes, according to federal complaint data.”); Kate Berry, AMERICAN BANKER, Why

are complaints about credit bureaus soaring? (Apr. 30, 2021), https://www.americanbanker.com/news/why-are-

complaints-about-credit-bureaus-soaring (“Yet the number of complaints to the Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau about credit reporting issues soared last year. Equifax, Experian and TransUnion were directly named in

246,000 direct complaints last year, more than double in 2019.”).

71

See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, supra note 1 at 27 (“In 2011, the NCRAs received approximately 8 million

consumer contacts disputing the completeness or accuracy of one or more trade lines, public records, or credit header

information (identification information) in their files. Based on these contacts, the number of credit -active consumers

who disputed one or more items with an NCRA in 2011 ranges from 1.3% to 3.9%.”) (citations omitted).

72

See Equifax, supra note 3 at 70 (more than 1.6 billion trade lines). Consumers who do not have a credit report may

also have issues arising from the fact that they are not in the credit reporting system. See, e.g., Kenneth Brevoort,

22 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

consumers frequently submit complaints to all the companies involved, i.e., all of the CRAs to

which the information was furnished as well as the furnisher. These two characteristics—a large

footprint and the involvement of multiple companies–increase the prominence of credit

reporting complaints when considered in the aggregate and makes simple complaint volume

comparisons to other product markets inappropriate.

Figure 1 shows the breakdown of companies who were the subject of credit and consumer

reporting complaints since 2017. A large percentage of these complaints are submitted about the

NCRAs. From January 2020 to September 2021, the CFPB received more than 225,000

complaints about each of the NCRAs (and more than 700,000 about NCRAs, collectively).

Although the increase in complaints about the NCRAs accelerated in 2020 and 2021, this

upward trend precedes 2020. Complaint volume about other CRAs is also increasing—growing

from 3,600 complaints in 2019 to more than 4,300 in 2020.

Phillip Grimm & Michelle Kambara, supra note 3; Kenneth Brevoort and Michelle Kambara, Consumer Fin. Prot.

Bureau, CFPB Data Point: Becoming Credit Visible (Jun. 2017),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/BecomingCreditVisible_Data_Point_Final.pdf .

23 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

FIGURE 1: BREAKDOWN OF NCRAS AND OTHER RECIPIENTS OF CREDIT OR CONSUMER REPORTING

COMPLAINTS, BY YEAR

Significant numbers of credit or consumer reporting complaints are also submitted about

companies that furnish information to the NCRAs. In 2020, there were nearly as many credit

reporting complaints about furnishers as there were complaints about credit cards, and more

complaints were submitted about furnishing than were submitted about bank accounts.

73

Table 1 summarizes product-level complaint submissions for several products in 2020 and

illustrates that consumers submit more than twice as many credit or consumer reporting

complaints as the next most frequently complained about product (debt collection).

73

Many of the complaints that are redirected to another regulator are also complaints about the furnishing of

information by smaller depository institutions. In those cases, consumers are prompted to contact the institution’s

prudential regulator.

24 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

TABLE 1: SHARE OF CONSUMERS, COMPLAINTS, AND COMPLAINTS PER CONSUMER IN 2020 FOR THE

FIVE PRODUCTS WITH THE GREATEST PER CONSUMER COMPLAINT VOLUME

Share of

consumers

Share of

complaints

Complaints per

consumer

Credit or consumer reporting

35.1%

59.2%

3.41

Debt collection

18.6%

15.1%

1.64

Credit card

11.2%

6.6%

1.19

Checking or savings

9.9%

5.5%

1.13

Mortgage

9.7%

5.4%

1.13

3.1 Factors underlying complaint volume

increases

The CFPB has a unique perspective on the credit reporting marketplace. In addition to being

able to analyze differences in the complaint response performance at the NCRAs (Section 5), the

CFPB can analyze data to identify trends in the use of its complaint process.

In this section, the CFPB summarizes some of the factors contributing to the increase in credit

or consumer reporting complaint volume. There are many factors that plausibly could have

contributed to this increase (e.g., accommodations provided by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and

Economic Security (CARES) Act

74

; changes in regulatory guidance during the COVID-19

pandemic

75

; increased shopping for mortgage credit and mortgage refinance credit due to low

interest rates

76

; increased consumer awareness of the salience of credit reports). This section

will focus its discussion on the behavior of those who use the complaint process.

74

See generally Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, § 4021 (2020).

75

See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Statement on Supervisory and Enforcement Practices Regarding the Fair Credit

Reporting Act and Regulation V in Light of the CARES Act,

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_credit-reporting-policy-statement_cares-act_2020-04.pdf. See

also Letter from consumer advocacy organizations to Kathy Kraninger, Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau (Sep. 24, 2020),

https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/credit_reports/Letter-to-CFPB-urging-revocation-of-extra-time-for-disputes.pdf

(noting a dramatic increase in consumer complaints following implementation of guidance for CRAs).

76

Although not a statistically valid sample, many consumers the CFPB talk ed with mentioned mortgage credit, and

housing more generally, as a motivating factor for working on their credit.

25 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Consumers are submitting more complaints in each session

As shown in Figure 2, consumers who submit credit reporting complaints are increasingly

submitting multiple complaints to the CFPB in a single session. Several factors may explain this

change in complaint behavior. First, with increased access to credit reports and scores,

consumers’ awareness of the actors making up the credit reporting system may be increasing.

77

Second, conversations with consumers suggest that eligibility for mortgage credit is a priority for

many consumers who review their credit history.

78

Because the standard credit report used in

residential mortgage transactions includes data from all three NCRAs (i.e., the so called “tri-

merge report”), these consumers may be more likely to submit complaints about all three

NCRAs because of their exposure to all three companies.

79

Finally, to the extent that consumers

are working with third parties or consulting educational resources, those third parties and

resources are likely to be aware of all three NCRAs and furnisher obligations, which may also

contribute to this increase.

80

77

See Blog, Liane Fiano, Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Protecting your credit during the coronavirus pandemic (Jul.

29, 2020), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/protecting-your-credit-during-coronavirus-pandemic/

(“Right now, it’s easier than ever to check your credit report more often. That’s because everyone is eligible to get free

weekly online credit reports from the three nationwide credit reporting agencies: Equifax, Experi an, and

Transunion.”).

78

Check ing credit is often considered among the first steps in purchasing a home. See, e.g., Blog, Erica Kritt,

Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Buying a home? The first step is to check your credit (Jan. 9, 2017),

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/buying-home-first-step-check-your-credit/ (“[I]f you are thinking

about buying a home this year, let’s make a plan. The first step: Check your credit.”); Freddie Mac, Understanding

your credit, https://myhome.freddiemac.com/buying/understanding-your-credit (“Your credit score and history play

a prominent role in determining your eligibility for a mortgage. As such, it's vital you recognize the value of having

strong credit when buying a home.”).

79

Several consumers connected their credit scores with the current low interest rate environment explic itly. It is

possible that consumers, aware that low mortgage interest rates are likely to be transitory, are much more motivated

to work on their credit currently. This factor may also be driving consumers to engage third parties.

80

See, e.g., Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, supra note 65 (providing information for how to dispute errors on credit

reports and providing contact information for the NCRAs).

26 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

FIGURE 2: AVERAGE NUMBER OF CREDIT OR CONSUMER REPORTING COMPLAINTS SUBMITTED PER

COMPLAINT SESSION BY QUARTER

Consumers are increasingly returning to the complaint process

The share of complaints submitted by consumers who previously submitted complaints

increased over the last year. In 2019, approximately 35% of complaints were submitted by

consumers who had previously submitted a complaint (Figure 3). That share increased to more

than 50% of complaints in the most recent quarter. The timing of this transition lags behind the

general increase in complaints that began in March 2020. As discussed in Section 5, many

consumers did not receive a substantive response to their initial complaints about the NCRAs.

These non-substantive responses can increase the total number of complaints when dissatisfied

consumers submit a subsequent complaint with the hope that their original issue will be

addressed. The CFPB has a process for companies to identify—and return—duplicate complaints

when consumers submit a complaint that does not describe or include any new issue, instance,

or information. From January 2020 to September 2021, the NCRAs returned fewer than 1% of

complaints to the CFPB using this process.

FIGURE 3: QUARTERLY SHARE OF CREDIT OR CONSUMER REPORTING COMPLAINTS WHERE

CONSUMER PREVIOUSLY SUBMITTED CREDIT OR CONSUMER REPORTING COMPLAINTS

27 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Third parties are using the complaint process

The Dodd-Frank Act directs the CFPB to accept complaints from consumers and their

representatives, which include an agent, trustee, or representative acting on behalf of an

individual.

81

The CFPB’s online complaint form permits complaints to be submitted by

consumers or third parties acting on their behalf, and it expressly states that third parties must

disclose their involvement.

82

The form further requires consumers and those acting on their

behalf to attest to the truthfulness of their submission to the CFPB.

83

When a third party

submits a complaint on behalf of a consumer but lacks authority to act on their behalf,

companies are able to respond to the CFPB via an administrative response process.

84

Administrative responses allow companies to return complaints to the CFPB with an

explanation as to why the company is not providing a substantive response to the complaint.

85

Complaints returned with administrative responses are not currently made publicly available in

the Consumer Complaint Database.

86

The CFPB maintains processes and procedures to protect the integrity of the complaint system.

It has refined, and continues to refine, these processes to detect and discontinue the processing

of complaints where the CFPB has reason to believe that third parties are not disclosing their

involvement in the complaint process.

87

The more than 3,200 companies that responded to

complaints in 2021 play an important role in informing these processes. When these companies

suspect that an unauthorized third party is involved in a complaint submission, they typically

communicate with the consumer to confirm that they authorized the complaint submission.

81

See 12 U.S.C. § 5511(c)(2) and 12 U.S.C. § 5481(4).

82

In Step 5, the online complaint form asks, Who are you submitting this complaint for? Users can select from either

Myself (I am submitting this complaint for myself) or Someone else (The consumer has authorized me to submit this

complaint for them). See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Complaint Form,

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/complaint/getting-started/.

83

The complaint form requires that users attest to their submission (“The information given is true to the best of my

knowledge and belief. I understand that the CFPB cannot act as my lawyer, a court of law, or a financial advisor.”).

84

When a company identifies a complaint that was submitted by or includes an unauthorized third party, they may

use administrative response options and describe the basis for determining the named consumer did not submit the

complaint or authorize submission of the complaint on their behalf.

85

The CFPB does not request a response in limited circumstances. For example, a company is not required to

respond to a complaint when it is in active litigation with a consumer.

86

See Disclosure of Consumer Complaint Narrative Data , supra note 14. See also Consumer Complaint Database,

supra note 14, Filtered Results in the Consumer Complaint Database (showing an effect of changing NCRA response

behavior over time; filtered to display complaints closed by the NCRAs’ complaints with Closed with monetary relief,

Closed with non-monetary relief, or Closed with explanation).

87

Complaints identified under this process are not forwarded to companies and are not currently published in the

Consumer Complaint Database; instead, the CFPB sends a response letter or email to the individual listed on the

submission, informing them that their complaint will not be processed and noting the steps they may take to submit a

complaint.

28 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

When companies identify complaints submitted without the authorization of the consumer, the

CFPB is able to use this information to prevent future submissions by such unauthorized third

parties.

The NCRAs disregard this process and do not take available steps to distinguish between

complaints authorized by the consumer and those not authorized by the consumer. Instead, the

NCRAs use proxies (e.g., similarity in narrative text) to identify complaints they suspect, though

have not confirmed, were submitted by a third party.

88

The NCRAs then use this speculative

assessment to justify not responding to the issue(s) raised in a complaint.

The NCRAs do not respond to complaints they suspect are submitted by third parties because

they inappropriately conflate different obligations.

89

Under existing FTC guidance (and some

case law), NCRAs do not need to investigate disputes submitted by third parties, such as credit

repair organizations.

90

The FTC guidance concerns disputes submitted under FCRA Section

611(a). The guidance does not address duties to review complaints transmitted by the CFPB

under FCRA section 611(e). This exception in the dispute investigation obligation does not apply

to covered complaints submitted to the CFPB. The CFPB expects that companies, including the

NCRAs, should reasonably review and respond to complaints legitimately submitted by a third

party on behalf of a consumer, and there is no guidance or caselaw precedent to the contrary.

In conversations with consumers who submitted complaints that were identified by the NCRAs

as having met their definition for credit repair, consumers described varied personal

experiences.

91

Some consumers stated that they had not received any outside assistance, but had

used freely available online resources, such as guidance provided by the CFPB and the FTC.

Others stated that they had completed credit self-help trainings, received guidance from social

media influencers, or relied on other sources of credit education. Other consumers

88

The CFPB has observed complaints where its sample letters to dispute information on a credit report, and language

recommended by the FTC’s guidance, do not receive a response from the NCRAs because the language met their

criteria for suspected third-party involvement. This suggests that the NCRAs may not be examining the quality or

origin of the forms they identity and highlights the issue with using template language as a proxy for unauthorized

complaint submissions.

89

Because the NCRAs do not respond to submissions they deem to be from third parties, credit repair organizations

are incentivized to conceal their involvement in the complaint process.

90

See, e.g., Fed. Trade Comm’n., 40 Years of Experience with the Fair Credit Reporting Act: An FTC Staff Report with

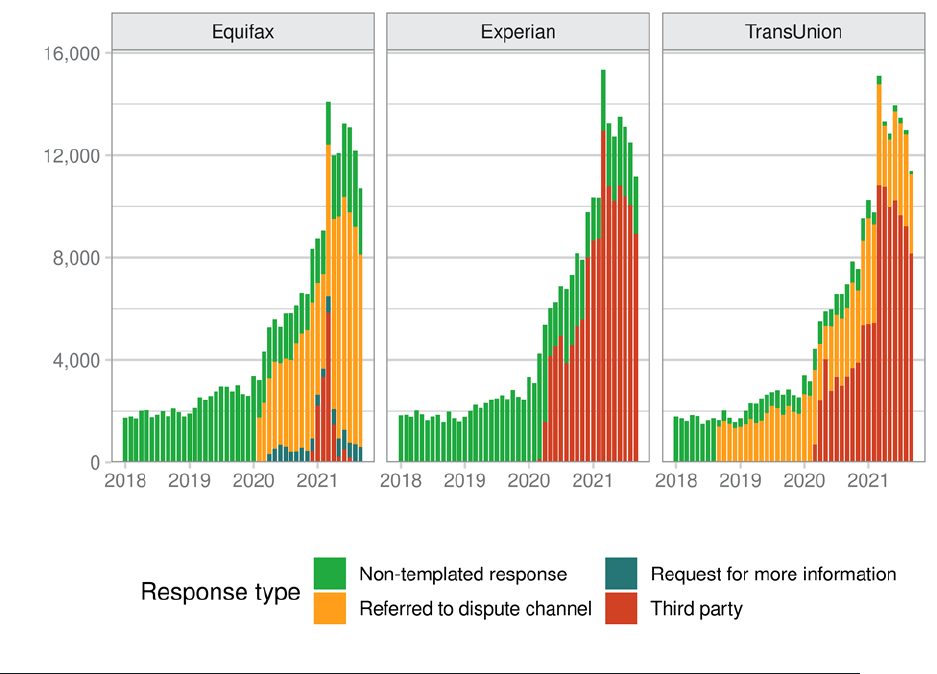

Summary of Interpretations (Jul 2011), https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/40-years-