(1881)

ARTICLE

CONTRACT PRODUC TION IN M&A MARKETS

STE PHEN J. CHOI,

†

MITU G ULATI,

††

MATTHEW JENNEJOHN

†††

&

ROBERT E. SCOTT

††††

Contract scholarship has devoted considerable attention to how contract terms are

designed to incentivize parties to fulll their obligations. Less attention has been paid

to the production of contracts and the tradeos between using boilerplate terms and

designing bespoke provisions. In thick markets everyone uses the standard form despite

the known drawbacks of boilerplate. But in thinne r markets, such as the private deal

M&A world, parties trade o costs and benets of using standard provisions and

customizing clauses. This Article reports on a case study of contract production in the

M&A markets. We nd evidence of an informal information network that transforms

bespoke changes in contract terms into industry-wide standard provisions. This

organic coordination structure leads to both market-wide coordination as well as a

diversity in this response as individual actors implement bespoke variations of the

new standard.

†

Bernard Petrie Professor of Law and Business, New York University School of Law.

††

Perre Bowen Professor of Law and John V. Ray Research Professor of Law, University of

Virginia School of Law.

†††

Professor of Law, BYU Law School.

††††

Alfred McCormack Professor Emeritus of Law, Columbia Law School. The authors thank

Ken Ayotte, Elisabeth de Fontenay, Jerey Dutson, Peter Lyons, Peter Molk, Michael Ohlrogge,

Samir Parikh, George Triantis, Glenn West, and participants at the University of Pennsylvania Law

Review’s symposium on Debt Market Complexity for comments, the editors of the Law Review for

their improvements, and to Sarah Lucas, Miranda Bailey, Tyler Baird, Paige Dallimore, C.J.

Jasperson, Alexandra Jorgensen, Jennifer Kimball, Tara Lee, Emily Livingston, Mickala Mahaey,

Samuel McMurray, Kelly Miles, Taylor Petersen, Aubrey Reed, Ethan Schow, Maria Whitaker,

Teresa White, and Kyle Wilson for research assistance. Thanks to Annalee Hickman Pierson and

Iantha Haight for library support. Finally, thanks to our thirty respondents.

1882 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

I

NTRODUCTION............................................................................ 1882

I. T

HE PRODUCTION OF CONTRACTS IN BOTH THIN AND T HI CK

MARKETS ............................................................................... 1888

A. Bespoke Contracting in Thin Markets...........................................1889

B. Production Eciencies in Thick Markets ...................................... 1891

C. The Collective Action Problem and the Role of the M&A Network...1893

II. CONTRACTING OVE R FRAUD: INCORPORATING NEW LAW

INTO

STANDARD TERMS ......................................................... 1895

A. From No-Reliance Clauses to the Fraud Carve-Out .......................1895

B. ABRY Partners: From the Fraud Carve-Out to Limited Fraud

Clauses .................................................................................... 1897

III. U

NPACKING THE NETWORK ....................................................1899

A. Leading Law Firms as a Spider................................................... 1901

B. The Inuence of the Voluntary Spider...........................................1902

C. The Inuence of Multilevel, Collective Engagement .......................1903

D. Summary .................................................................................1905

IV. EMPIRICAL DATA AN D ANALYSIS ............................................. 1905

A. The Fraud Carve-Out ...............................................................1908

B. Dening Fraud : The Incidence of Limited Fraud Clauses................ 1910

C. Digging Deeper: Who Moved First and How Fast? ........................ 1912

D. Deeper Still: Variation in Limited Fraud Provisions ....................... 1916

C

ONCLUSION................................................................................ 1924

I

NTRODUCTION

Two separate economic objectives motivate the parties who form

commercial contracts.

1

A primary objective is to design contracts that induce

the parties to maximize the joint gains from transactions. This is the goal of

ecient contract design.

2

But contracting parties also pursue a second

objective: they must conceive and formulate the many legal terms and

conditions that implement their contract design. This is the goal of ecient

contract production. Until recently, the ecient production objective has been

largely unexplored. We know a great deal about how to design contracts to

motivate parties to invest optimally in their relationships, but we know less

1

Portions of the Introduction & Part I draw from Robert E. Scott, The Paradox of Contracting

in Markets, 83 L

AW & CONTEMP. PROBS. 71 (2020).

2

See Alan Schwartz & Robert E. Scott, Contract Theory and the Limits of Contract Law, 113 YALE

L.J. 541, 544-45 (2003) (“[C]ontract law should facilitate the eorts of contracting parties to

maximize the joint gains . . . from transactions [by solving the] canonical ‘contracting problem’ of

ensuring both ecient ex post trade and ecient ex ante investment . . . .”).

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1883

about the process of producing the widely-used contract terms that

implement the ecient design.

3

This is unfortunate because the production

process is the source of a fundamental tradeo: the factors that generate

eciencies in the production of contracts—standardization and economies of

scale—are the same factors that can undermine ecient design by

instantiating contract terms that do not (or no longer) maximize the parties’

joint gains. And the reverse is true: customized eorts to formulate terms

that implement an ecient de sign necessarily generate the ineciencies in

contract production that result from the inevitable loss of scale. As a

consequence, while partie s in thin markets may prefer more bespoke contracts

that minimize errors in design, parties in thick markets, where more and more

parties participate in the same or similar transactions, may prefer

standardization and economies of scale even at the risk of an increase in

design errors.

4

Recognizing this tradeo is the rst step toward answering an unresolved

question: how do contracting parties optimize between the ecient contract

production and ecient contract design? The challenge is to exploit

production eciencies without degrading the contract design that motivates

ecient performance.

5

In understanding how commercial parties respond to

this tradeo we can begin with a more precise identication of the production

costs of contracting. Contract drafters that are faithful agents are motivated

to optimi ze two principal costs: the cost of production eorts and design error

3

For examples of eorts to understand the production problem, see Stephen J. Choi, Mitu

Gulati & Robert E. Scott, The Black Hole Problem in Commercial Boilerplate, 67 D

UKE L.J. 1, 12-14

(2017) (exploring how certain contract provisions are created and evolve over time); see also Robert

Anderson & Jerey Manns, The Inecient Evolution of Merger Agreements, 85 G

EO. WASH. L. REV.

57, 59-61 (2017) (analyzing the evolution and relatedness of public company merger agreement

language); Barak Richman, Contracts Meet Henry Ford, 40 H

OFSTRA L. REV. 77, 85-86 (2011)

(postulating that organizational tendencies toward the routine may explain the reproduction of

boilerplate language in contracts); D. Gordon Smith & Brayden G. Smith, Contracts as Organizations,

51 A

RIZ. L.REV. 1, 2 (2009) (arguing that recent studies of contract language have been too narrowly

focused on economic theories of contracting and should take organizational theory into account);

Kevin E. Davis, Interpreting Boilerplate 1-2 (N.Y.U . Ctr. for L., Econ., & Org., Working Paper No .

10-21, 2010), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1618925 [https://perma.cc/JCE9-

SBDU]; Weija Rao & Cree Jones, Sticky BITs, 61 H

ARV. INT’L L.J. 357, 360 (2020) (analyzing

national uptake of new bilateral treaty provisions in response to unexpected judicial treaty

interpretations); Julian Nyarko, Stickiness and Incomplete Contracts, 88 U.

CHI. L. REV. 1, 6-7 (2021)

(identifying and explaining the absence of bargaining over dispute settlement clauses in commercial

transactions).

4

For our purposes, a market is thick when many parties participate in similar transactions and

will benet from coordinated responses to the contracting environment. Thus, a market thickens

when more and more parties participate in the same or similar transactions.

5

As we discuss in Part I, when markets are thick in the sense that many actors face similar

challenges in their dealings, the aected parties often will institutionalize their innovative contract

forms and terms through collective action. Infra Part I.

1884 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

costs.

6

Eorts and error costs are substitutes: the more time and eort a

drafter spends in producing a contract, ceteris peribus, the lower the risk of

design error. Conversely, the less time and eort invested in production the

higher the risk of unwanted errors.

To frame the problem, we begin by examining the poles of a production

continuum with maximum production eort cost and minimum design error

cost at one pole and minimum production eort cost and maximum design

error cost at the other. At one pole, parties in thin markets where contracting

is bilateral are impelled by their circumstances to use substantial eorts in

production that will tend to minimize design errors for each transaction. For

example, the parties can avoid errors by updating each contract in response

to legal or economic conditions: coordinating with other transactors is not a

concern.

7

By contrast, at the other pole, where markets are thick, traders can

exploit economies of scale by standardizing the production of the contracts

that govern their transaction. Standardization substantially reduces the

transaction costs of producing contract terms by providing a prescribed menu

of incentive-compatible terms. However, this standardization, most clearly

found in large liquid markets such as those for cor porate and sovereign bonds,

leads to the ineciencies common to boilerplate: deviating from the standard

is costly and updating requires coordination among many diverse interests.

Thus, while boilerplate te rms require minimal investment in production cost,

they are sticky, resistant to change, and subject to the anomalies we have

previously described as “black holes”

8

and “landmines”

9

—errors that remain

in the contract even in the face of adverse legal consequences.

10

6

We dene design error costs as the failure of any contract term to embody optimal contract

design; that is the failure to formulate a term that will (together with the other contract terms)

maximize the expected contractual surplus.

7

In eect, it is the contracting parties’ attempt to maximize “the incentive bang for the

contracting-cost buck.” Robert E. Scott & George G. Triantis, Anticipating Litigation in Contract

Design, 115 Y

ALE L.J. 814, 823 (2006).

8

See Stephen J. Choi, Mitu Gulati & Robert E. Scott, The Black Hole Problem in Commercial

Boilerplate, 67 D

UKE L.J. 1, 3 n.2 (2017) (describing a contractual “black hole” as occurring when a

clause’s original meaning is “lost entirely by the process of repetition and the insertion of random

variations”).

9

See Robert E. Scott, Stephen J. Choi & Mitu Gulati, Contractual Landmines, 41 YALE J. REG.

(forthcoming 2023) (describing contractual landmines as “vague and apparently purposeful changes

to standard language that increases a creditor’s nonpayment risk, coupled with blatant errors in

expression and drafting and a continuing use of inapt terms that were historically imported from

corporate transactions”).

10

For discussions of how boilerplate terms become resistant to change, see Charles J. Goetz &

Robert E. Scott, The Limits of Expanded Choice: An Analysis of the Interactions Between Express and

Implied Contract Terms, 73 C

ALIF. L. REV. 261, 265-73 (1985); Marcel Kahan & Michael Klausner,

Standardization and Innovation in Corporate Contracting, 83 V

A. L. REV. 713, 719 (1997) (describing

how standardized contract terms create learning benets because the terms have been commonly

used); Stephen J. Choi, Robert E. Scott & Mitu Gulati, Revising Boilerplate: A Comparison of Private

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 188 5

We draw the distinction between bespoke contracting and standardized

contracting more sharply in this paper than what we generally observe in

commercial contracting. Reality is much less clear than any stylization

designed to illuminate the dierences between the two contracting practices.

Inevitably, the lines between the two production techniques are blurred. The

best way to understand this distinction, therefore, is to visualize bespoke

contracting and standardized contacti ng as poles of a continuum where many

markets along the continuum exhibit features of both.

In this Article, we examine one such market: M&A contracts that are

transactions that fall between the poles of the continuum described above.

The M&A market often involves large, sophisticated parties with the

resources and, on occasion, the motivation to craft bespoke contracts. The

market also includes a number of repeat players (including private equity

funds and their law rms) that benet from employing standardized terms

across deals that provide both greater certainty than bespoke terms and

reduced transactional costs. In such a market, we posit that parties will value

both the option to employ bespoke terms and the ability to draw upon a pool

of standardized terms. With such a preference, we expect a market structure

that allows for some degree of coordination to develop standardized terms as

well as the freedom for individual actors to employ their own bespoke terms.

The features of the M&A market display such a str ucture.

The lawyers drafting these M&A agreements, and particularly the subset

of pr ivate equity M&A contracts, belong to a network of practitioners that

meet frequently at conferences, often together with the judges who decide

litigated cases, to discuss new developments.

11

These conferences act as focal

points for discussion and coordination over how contract terms should reect

new developments in the law and “best” contracting practices. We use

interviews with market participants as well as data drawn from a random

sample of M&A contracts to determine how and when drafters in this

network respond to novel caselaw developments. As a focal point, the

conferences help encourage a degree of standardization. But individual

attorneys enjoy the freedom and resources (partic ularly from their private

equity clients who will be concerned about individual liability) to design their

own variations on proposed standards.

12

Consequently, the contracts

and Public Company Transactions, 2020 WIS. L. REV. 629, 629-30 [hereinafter Revising

Boilerplate](discussing agency costs and coordination diculties as sources of stickiness in

boilerplate terms).

11

Matthew Jennejohn, Julian Nyarko & Eric Talley, Contractual Evolution, 89 U. CHI. L. REV.

901, 908-09 (2021).

12

See, e.g., Glenn West, Protecting the Private Equity Firm and Its Deal Professionals From the

Obligations of its Acquisition Vehicles and Portfolio Companies, W

EIL GLOB. PRIV. EQUITY BLOG (May

23, 2016), https://privateequity.weil.com/features/protecting-private-equity-rm-deal-

1886 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

produced by this structure are characterized by a mixture of standardized

terms—representations and warrantie s that are market terms used

throughout the industry—as well as bespoke negotiations over terms that

reect new developments in the caselaw (drawn from the Delaware Court of

Chancery where parties typically litigate).

13

Our particular focus is on novel contract doctrines that invite sellers to

erect barriers to buyers’ claims for rescission based on fraud. The preliminary

evidence we provide is consistent with the hypothesis that the private equity

network deploys an organic, multilevel process that coordinates eorts to

contract over fraud; it is a process that in time produces standardized terms

dealing with fraud that are used throughout the market.

The Article proceeds as follows. Part I sets out the tradeos involved in

contracting in dierent markets in some detail. We rst explain how parties

in thin or bilateral contracting markets optimize the costs of production for

each transaction by adjusting the allocation of costs between the front-end

costs of drafting ex ante agreements and the expected back-end costs of

enforcing those contracts . This bespoke balancing of ex ante and ex

postproduction costs is driven by the degree of uncertainty unique to that

specic conte xt. These eorts to customize the individual contract are costly

but they do yield the most ecient contract for the production cost.

14

But as

markets thicken, traders in multilateral contracting environments can exploit

economies of scale by standardizing the production of the contract terms that

will govern all transactions in the market thereby reducing the transaction

costs of producing customized contract terms.

15

However, market

standardization leads to the ineciencies of boilerplate discussed above:

standardized contract terms resist adaptation to changed conditions.

16

professionals-obligations-acquisition-vehicles-portfolio-companies/ [https://perma.cc/HKX5-

LMPJ] (describing the process for courts to “pierce” the “corporate veil” and hold a corporation’s

owners or aliates liable for its actions).

13

See, e.g., Glenn West, Too Much Dynamite: The Non-Recourse and Survival Clauses Are Both

Subject to Delaware’s Built-In Fraud Carve-Out for Intentional Intra-Contr actual Fraud, W

EIL GLOB.

PRIV. EQUITY BLOG (Aug. 24, 2021), https://privateequity.weil.com/glenn-west-musings/too-much-

dynamite-the-non-recourse-and-survival-clauses-are-both-subject-to-delawares-built-in-fraud-

carve-out-for-intentional-intra-contractual-fraud/ [https://perma.cc/PJK9-GCJL] (prescribing

M&A deal terms that are responsive to the recent Delaware Court of Chancery decision in Online

Healthnow, Inc. v. CIP OCL Investments, LLC, 2021 WL 3557857(Del. Ch. Aug. 12, 2021)).

14

See Scott & Triantis, supra note 7, at 836-37 (describing the tradeos between front-end and

back-end drafting of contracts).

15

For discussion, see Mark R. Patterson, Standardization of Standard-Form Contracts:

Competition and Contract Implications, 52 W

M. & MARY L. REV. 327, 331 (2010) (noting that these

common contractual formulations can reduce the need to negotiate new contracts).

16

See supra note 10 (citing sources on the stickiness of boilerplate terms).

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1887

Nevertheless, there is evidence that there are variations in the speed and

nature of adaptation across these markets .

17

In Part II, we frame the hypothesis that lawyers drafting private equity

acquisition contracts are able to respond in a coordinated fashion to new

developments in the law but do so in an “organic” fashion that results in

numerous variations driven by individual actors in a multilateral

environment. We use as our template the evolution of contract law over the

past twenty years, as De laware courts invited drafting lawyers to depart from

common law doctrine by contracting over fraud. Initially, as sellers

successfully negotiated for damage caps on their liability, buyers required a

carve-out from this limitation for any claims of fraud. Thereafter, Delaware

courts endorsed no-reliance clauses in which buyers armed that they were

not relying on any claims arising from extra contractual representations made

by sellers’ agents.

18

Subsequently, the Delaware Court of Chancery in ABRY

Partners v. F&W Acquisition armed the market status of the no-reliance

clauses that had become ubiquitous in the interim and also endorsed eorts

by sellers to limit their liability for intra-contractual fraud to evidence of

deliberate, intentional fraud.

19

The question Part II poses, then, is whether

and in what form drafters, individually or as members of a network,

incorporate these novel fraud-limiting provisions into their private equity

acquisition agreements.

Part III tests the coordination hypothesis by positing that the parties to

M&A deals, and private acquisition deals in particular, belong to a network

that facilitates the exchange of information needed to revise standard terms.

20

We explore the possible pathways that drafters in this network use to

transform bespoke eorts to limit fraud claims into standardized boilerplate.

Here we report on interviews with thirty practitioners who are experienced

in M&A deals. We asked our respondents how and in what ways initial eorts

to contract over fraud evolve into market-wide standardized terms. This

17

For a prior examination of this variation, see Revising Boilerplate, supr a note 10.

18

Infra Part II.A.

19

891 A.2d 1032, 1034-35 (Del. Ch. 2006). Since some states continue to follow the common

law prohibition on contracting over fraud, drafters were also urged to amend their governing law

clauses to de signate Delaware as the choice of law for both contract and tort claims in order to

prevent buyers from pursuing their fraud claims in jurisdictions that followed the older common

law rules. See Choi, Gulati & Scott, infra note 43 (discussing governing law clauses).

20

Networks are mechanisms for coordination and cooperation between formally independent

but functionally interdependent entities. For prior work that studies advisory networks as conduits

for information transfer and coordination among deal lawyers, see Kristina Bishop, Matthew

Jennejohn & Cree Jones, Top Ups and “Telephone” 1 (BYU L. Sch. Working Paper, 2022),

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4313301 [https://perma.cc/59HW-MN7K];

Matthew Jennejohn, Julian Nyarko & Eric Talley, Contractual Evolution, 89 U.

CHI. L. REV. 901,

908-09 (2021); Matthew Jennejohn, The Architecture of Contract Innovation, 59 B.C.

L. REV. 71, 73

(2018).

1888 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

evidence suggests that drafters can overcome the collective action problems

that impede ecient contract design by exploiting an informal network that

organizes their loose web of relationships: parties rely on the information

generated in the network to reach a consensus that transforms novel and

initially “bespoke” terms into widely accepted “market” terms. This focus on

organic coordination conceives of the contracting parties in this world as

members of a commercial network that communicates important information

through several dierent pathways.

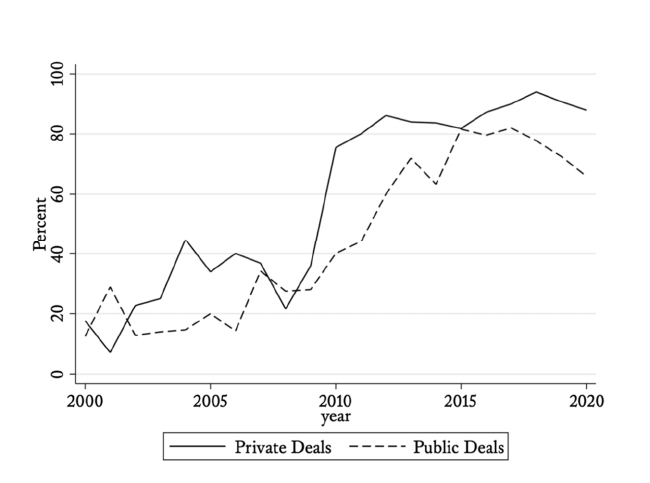

In Part IV we present a preliminary quantitative empirical analysis that is

consistent with the claim that multilay ered pathways serve as unique

mechanisms of coordination in the private equity acquisitions market. That

analysis reveals a widespread, if gradual, diusion of fraud carve-outs in the

M&A market, rst in private target transactions and then in public target

deals.

21

The subsequent practice of narrowly dening fraud in the acquisition

agreement—an important step if the full advantage of ABRY is to be

obtained—followed a similar trajectory.

22

Both patterns are consistent with a

coordination process roote d in information sharing within the network, as

opposed to change driven by a single institution or hierarchy in a top-down

process. We then dig deeper into the diusion process, asking what dynamics

within the network appear to drive the adoption of a clause narrowly limiting

the fraud carve-out.

Contrary to what we might have expected based on prior research on other

markets, such as the sovereign bond market,

23

we nd no evidence that a

vanguard of elite law rms leads the adoption of a new contract term. If

anything, it appears that the top advisory rms lagged others in the adoption

of a term that limits the fraud carve-out to intentional fraud.

24

We also nd

evidence that is suggestive of multiple diusion mechanisms—from the

writings of an inuential practitioner to dissemination of market studies by

the American Bar Association’s M&A Subcommittee—operating in

tandem.

25

I. T

HE PRODUCTION OF CON TRACTS IN BOTH THI N AND THICK

MARKETS

In this Part, we describe the pole s of the continuum formed by ecient

design at one pole and ecient production at the other. Ecient design

21

See infra Part IV.A.

22

Id.

23

See Choi & Gulati, Innovation in Boilerplate, infra note 82.

24

Infra Part IV.C.

25

An analysis of the language advisors use in dening fraud reveals heterogeneity that persists

over time, consistent with the impetus for adoption coming from multiple sources. Id.

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1889

occurs in bespoke transactions where parties’ cost considerations are limited

to optimizing the costs of production for that contract only. Here, the

transaction costs of producing the contract terms are high but may be justied

by the resulting design eciencies. At the other pole we nd the fully

standardized contract, where a thick market produces boilerplate contract

terms that substantially reduce the costs of production so long as parties use

the standard terms. The tradeo is that reliance on these standard terms

necessarily leads to obsolescence and errors that inevitably emerge in the

boilerplate.

A. Bespoke Contracting in Thin Markets

Bespoke transactions are characteristic of thin markets where the actors

are few and scattered, and thus require substantial eorts to design and

produce contracts eciently.

26

Here, the goal is to weigh production costs

against the incentive gains in achieving ecient investment and trade in the

given transaction. The thinness of the market removes any scale economies

from the production process. This leads to parameter specic strategies in

which individual dyads shift costs of production between front-end

transaction costs and back-end enforcement costs in dierent ways. It is the

particular balancing of front-end and back-end costs within each trans action

that optimizes contractual incentives.

27

The particular allocation of costs

between front and back-end in each transaction is driven by the degree of

uncertainty in that economic environment.

28

Thus, when the level of

uncertainty is low, contract designers can anticipate and address (most of) the

future states of the world and specify what should happen in each possible

state.

29

In this case, most of the costs of production are allocated to initial

eorts in negotiating and formulating fully specied contingent contract

terms.

26

Bespoke transactions are tailor-made contracts designed to t the requirements of a single

transaction or transaction type. For discussion, see Ronald J. Gilson, Charles F. Sabel & Robert E.

Scott, Text and Context: Contract Interpretation as Contract Design, 100 C

ORNELL L. REV. 1, 43-44

(2014); see also Alan Schwartz & Joel Watson, The Law and Economics of Costly Contracting, 20 J.L.

ECON. & ORG. 1, 2-5 (2004) (identifying the balancing that occurs between contracting and

renegotiation costs).

27

See Scott & Triantis, Anticipating Litigation, supra note 7, at 817 (“[T]he mix of precise and

vague terms that characterize the typical commercial contract can be framed as the product of a

tradeo that the parties have made in investing in the front end or back end of the contracting

process, based on their particular circumstances.”).

28

Gilson, Sabel & Scott, Text and Context, supra note 26 at 55-57 (“In general, legally

sophisticated parties designing bespoke contracts choose between text and context by trading o the

front-end (or drafting) costs of contracting and the back-end (or enforcement) costs.”).

29

Cf. Scott & Triantis, Anticipating Litigation, supra note 7, at 816 (explaining why parties

sometimes consent to contracts which fail to address various contingencies appropriately).

1890 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

As uncertainty increases, however, eorts to craft bespoke state

contingent contracts come under pressure and parties are motivated to shift

costs to the back-end enforcement process.

30

Here, parties design more

exible relational contracts by using standards governing key terms such as

price, quantity, and eort that delegate ex post discretion to courts.

31

Distribution contracts are an example in this environment of the eciency

advantages of coupling an explicit statement of obligation with a broad ‘best

eorts’ standard that gives a subsequent court discretion over how the

obligation is enforced.

32

Technological change has raised the level of

uncertainty even higher. As a consequence, more complex collaborative

agreements have emerged that require more creative eorts to shift additional

resources to the back end.

33

In these collaborative agreements, the few formal

elements of the contract are designed to facilitate the growth of trust that, in

turn, will regulate the substantive elements of the parties’ relationship. Here,

drafters create a formal governance structure designed to induce complex

cooperative behaviors that are braided with a few explicit obligations.

34

In all of these bespoke settings, where resource allocation choice s are

inuenced primarily by the level of uncertainty, the costs of production are

assessed only by reference to the incentive gains produced in that particular

transaction. An appropriate analogy is the relationship between the costs of

crafting a beautiful piece of furniture by hand and the value derived from its

sale to an appreciative buyer. But those considerations are inapt once the

market for furniture of this style increases and the cabinetmaker now

contemplates making many sales of similarly designed pieces to many buyers.

When markets thicken and scale economies can be realized—both in th e

30

Gilson, Sabel & Scott, Te xt and Context, supra note 26, at 56-57 (“[T]he greater the

uncertainty associated with a contract—the more dicult for the contracting parties to specify all

the future states of the world in which the contract will have to be performed . . .—the more the

contracting parties confront a dilemma.”).

31

Allowing exibility (or discretion) in relational contracts saves parties the transaction costs

from continually having to update or renegotiate price or quantity in light of changed circumstances.

In long-term procurement agreements, for example, an uncertain future motivates the parties to

expend substantial design eorts on contextualized standards that permit quantity and price to be

adjusted as circumstances change over time. See Alan Schwartz & Robert E. Scott, The Common Law

of Contract and the Default Rule Project, 102 V

A. L. REV. 1523, 1530 n.19 (2016) (describing how default

standards shift costs from the front to the back end of the contracting process).

32

See Scott & Triantis, supra note 7, at 851–56 (discussing how parties contextualize standards

to t their circumstances).

33

For discussion of these collaborative contracts and contracting for innovation, see generally

Ronald J. Gilson, Charles F. Sabel & Robert E. Scott, Contracting for Innovation: Vertical

Disintegration and Interrm Collabor ation, 109 C

OLUM. L. REV. 431 (2009).

34

For a discussion of the interplay between the formal governance structure and the informal

bonds of trust that it generates through iterative exchanges of information between the parties, see

generally Ronald J. Gilson, Charles F. Sabel & Robert E. Scott, Braiding: The Interaction of Formal

and Informal Contracting in Theory, Practice, and Doctrine, 110 C

OLUM. L. REV. 1377 (2010).

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1891

underlying economic good and in the contract that regulates the trade—the

cost of producing any given contract becomes economically relevant. It is in

these multilateral contracting environments that production eciencies can

undermine ecient design.

B. Production Eciencies in Thick Markets

Producing contracts more eciently in large multilateral markets such as

sovereign and corporate debt creates value that is shared among the market

participants. Contract production eciencies result pr imarily from th e

standardization of contract terms that are enabled by economies of scale.

35

In

these thick markets where there is scale in the production of an economic

good, standardized contract terms facilitate the scaling of the associated

contracts as well. Beyond the savings in transaction costs, standardized terms

bring to bear a collective wisdom and experience of ways to avoid mistakes in

designing terms.

36

Standardized terms also reduce learning costs by providing

a uniform system of communication: repetition reduces the cost that others

must expend in learning the meaning of the clause.

37

Standardization in the production of boilerplate is, however, a double-

edged sword: the eciencies that reduce the costs of producing contracts also

make it costly for parties to deviate from the standard and are the very source

of the contracts’ design ineciencies. Standard-form contract terms are

dierent from the optimal terms in a bespoke commercial contract. The

certainty that standardization imparts to the market limits the capacity of

contract drafters in large and liquid markets to draft vague standards designed

to grant discretion to later courts to enforce contractual rights. Here, drafters

are functionally incapable of shifting the costs of production fr om the front

end of the contracting process to the back end as they do when designing

35

See Robert E. Scott, The Paradox of Contracting in Markets, 83 LAW & CONTEMP. PROBS. 71,

72-73 (2020) (“[A]s markets thicken, traders can exploit economies of scale in multilateral contracting

markets by standardizing the production of the contracts that govern the exchange transaction.”).

36

The unique benets of standardization derive from the process by which standard

formulations of terms evolve and gain a distinct, recognized, and consistent meaning within the

market. This evolutionary process tests combinations of terms for dangerous but latent defects. Over

time, the consequences of standard formulations are observable over a wide range of transactions,

permitting the removal of ambiguities and inconsistencies. Goetz & Scott, supra note 10, at 265-73.

In this way, mature standardized terms become validated by experience and are therefore safer than

new and innovative formulations of terms. See T

INA L. STARK, NEGOTIATING AND DRAFTING

CONTRACT BOILERPLATE § 1.02 (2003) (observing that provisions that have been used repeatedly

develop a “hallowed status” and have now been blessed).

37

Marcel Kahan & Michael Klausner, Standardization and Innovation in Corporate Contracting,

83 V

A. L. REV. 713, 719 (1997) (describing that standardized contract terms create learning benets

because the terms have been commonly used).

1892 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

bespoke contracts in bilateral markets.

38

This limitation puts even more

pressure on drafters in these markets to rely on fully specied terms that will

motivate parties to invest and trade eciently.

Unfortunately, the very elements of xed and unchanging meaning that

make standardized terms attractive are the same elements that can contribute

to the erosion of that meaning over time. The problem is obsolescence;

standardized terms are sticky and thus slow to change in response to changes

in contract law and doctrine.

39

Indeed, obsolete standardized terms in

boilerplate contracts may over time lose any recoverable meaning, creating

what we refer to as a contractual black hole.

40

Over time, some standardized

terms are used so consistently that they lose meaning; they are used simply

because ever yone uses them.

41

Matters get worse if legal jargon is overlaid on

standard linguistic formulations.

42

Drafters working with standard-form

language that has been repeated by rote for many years often lack

understanding of the contemporary purpose(s) served by the boilerplate

terms. Drafting marginal modications to t the goals of a transaction while

38

An illustration of the diculty of drafting standards in multilateral markets for courts to

interpret ex post is the largely futile eorts of parties seeking to have courts enforce the ubiquitous

material adverse change clause (MAC) in merger and acquisition contracts. The MAC is designed

as a standard term that will permit the acquirer to abandon the merger in light of specied events

that occur after signing but before the deal closes. Eric L. Talley, On Uncertainty, Ambiguity, and

Contractual Conditions, 34 D

EL. J. CORP. L. 755, 760-61 (2009)(discussing the purpose and design of

the modern Material Adverse Eect provision). Delaware courts rarely nd a material adverse

change sucient to trigger a MAC and justify the acquirer backing out of a merger deal. See, e.g.,

In re IBP, Inc. S’holders Litig., 789 A.2d 14 (Del. Ch. 2001 )(declining to allow a buyer to terminate

a transaction on the basis of an alleged Material Adverse Eect); Hexion Specialty Chems., Inc. v.

Huntsman Corp., 965 A.2d 715, 722 (Del. Ch. 2008)(granting a request for specic performance,

nding that there had not been a MAC); Frontier Oil v. Holly Corp., No. CIV.A. 20502, 2005 WL

1039027, at *37 (Del. Ch. Apr. 29, 2005)(determining that nondisclosure of threatened litigation,

which had not been proved likely to create a Material Ad verse Eect, was not a breach of warranties

and representations sucient to permit nonperformance), judgment entered sub nom., Frontier Oil

Corp. v. Holly Corp. (Del. Ch. 2005); Channel Medsystems, Inc. v. Bos. Sci. Corp., No. CV 2018-

0673-AGB, 2019 WL 6896462, at *1 (Del. Ch. Dec. 18, 2019), judgment entered, 2019 WL 7293896

(Del. Ch. Dec. 26, 2019)(nding that the inaccuracy of statements due to fraud had not been proved

to rise to the level of a MAE); AB Stable VIII LLC v. Maps Hotels & Resorts One LLC, No. CV

2020-0310-JTL, 2020 WL 7024929, at *1-2 (Del. Ch. Nov. 30, 2020), judgment entered 2021 WL

426242, (Del. Ch. Feb. 5, 2021), and a ’d, 268 A.3d 198 (Del. 2021) (nding no MAE). The Court

of Chancery’s opinion in Akorn, Inc. v. Fresenius Kabi AG, 198 A.3d 724 (Table), 2018 WL 6427 137,

at *1 (Del. 2018) stands out as the sole exception to that long line of recent cases. The eect of courts’

reluctance to nd a MAC is that the MAC clause functionally becomes a standardized “no MAC”

term in the contract.

39

See supra note 10 (citing sources on the stickiness of boilerplate terms).

40

For discussion on this topic, see Choi, Gulati & Scott, supra note 3, at 3-4 n.2.

41

See Goetz & Scott, supra note 10, at 288-89 (explaining that “rote usage” of contract language

corrupts its meaning so as to ultimately become meaningless).

42

Id.

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1893

ignorant of the contemporary function of the contract’s boilerplate terms may

lead to errors in an eort to clarify the boilerplate.

43

C. The Collective Action Problem and the Role of the M&A Network

Given the important role that standardization plays in replicating

boilerplate terms in tens of thousands of commercial contracts in large

multilateral markets, and the non-trivial possibility that a court may err in

interpreting terms that are obsolete or encrusted with legal jargon, parties

have incentives in these markets to ensure that their standardized contract

terms are continually revised. Updating standard terms in these thick markets

is essential to preserving a common and contemporary meaning. Despite these

incentives, there is evidence that parties in multilateral markets often fail to

react to changes in contract law and doctrine and fail readily to convert

standardized terms into new and ecient formulations.

44

Inertia results from

costs that collectively deter an individual participant from revising the

standard terms. Participants in multilateral markets express a strong

preference for a standard package of terms because revision increases the

learning costs for potential traders.

45

Since the production of network

externalities is a primary value of standardized contracts, it follows that

standardized contract terms will be slow to change even after market

participants identify costly errors and ambiguities.

46

Meanwhile, the

ineciencies caused by linguistically obscure or obsolete boilerplate may not

be fully priced by the market.

47

There is a solution to the impediments that prevent individual traders in

large, multilateral markets from revising obsolete terms. Consider the

sovereign bond market as an example; if the market participants acted

together, they could coordi nate to create a network of traders who collectively

43

See Stephen J. Choi, Mitu Gulati & Robert E. Scott, Variation in Boilerplate: Rational Design

or Random Mutation?, 20 A

M. L. & ECON. REV. 1, 41 (2017) (describing this phenomenon in the case

of the pari passu clause in sovereign bonds); see also Stephen J. Choi, Robert E. Scott & Mitu Gulati,

Investigating the Contract Production Process, 16 C

AP. MKTS. L.J. 414, 425 (2021) (describing the impact

of lawyerly tinkering with the standard governing law clause).

44

See Variation in Boilerplate: Rational Design or Random Mutation?, supra note 43, at 41

(“Contract clauses that no one understands can [often] become part of the standard template, and

variations among those clauses that are largely meaningless can arise and even grow in usage.”).

45

See Anna Gelpern, Mitu Gulati & Jeromin Zettelmeyer, If Boilerplate Could Talk: The Work

of Standard Terms in Sovereign Bond Contracts, 44 L

AW & SOC. INQUIRY 617, 626-27 (2019)

(describing the preference for standard terms because they are simple and bring a sense of

legitimacy). This preference suggests that contract terms are more endogenous than is typically

assumed in models of contract where individual purchasers and sellers come to the market with their

individual preferences that are independent of those of other traders.

46

For discussion about this phenomenon, see Kahan & Klausner, supra note 37, at 727-29.

47

For a discussion of the diculty in pricing terms in these markets, see Contractual Landmines,

supra note 9, at 40 n.100.

1894 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

advance a new standard market term with a clear meaning and purpose. But

it is challenging in large multilateral markets to create a functioning network

that can coordinate the eorts of all the participants. In a recent study, we

compared the speed with which obsolete terms are revised in M&A

transactions with analogous sovereign and corporate bond contracts.

48

In each

market, the contracts contained a standard No Recourse clause that had

become obsolete over time. This left investors vulnerable to liability claims

based on tort and other equitable theories.

49

The emerging case law should

have motivated parties in all three markets to modify the obsolete clause to

better protect against these non-contractual claims.

50

The modication would

have been easy to implement. Yet the vast majority of the corporate and

sovereign bond contracts continued to use the obsolete No Recourse clause,

largely unchanged from previous decades, conrming the diculty of

revising terms in these markets.

51

By contrast, over fty percent of the private

M&A deal contr acts were revised following a series of industry meetings

discussing the changes in the caselaw.

52

Indeed, in the deals done by the top

ve law rms in the industry, every private deal contract was revised.

53

Parties in the private M&A deal market were better able to coordinate on

a standard revision via a combination of industry meetings and leadership

from the top law rms. By coalescing around a standard revision to the No

Recour se clause, the top rms overcame the reluctance of other drafters to

change the language unilaterally. In contrast, corporate and sovereign bond

contracts continued to use the obsolete No Recourse term, despite the

litigation risk.

54

These ndings suggest that there are variations across

markets both in the capacity for coordination and the willingness of key actors

to experiment with customized revisions.

The comparison between the M&A market and the bond market

highlights potential dierences between the two market types. In the M&A

market, and particularly its private deal variant, contracting parties have

devised mechanisms that support inter-party collaborations.

55

In contrast, the

48

See generally Revising Boilerplate, supra note 10.

49

Id. at 633-34.

50

Id. at 634-35.

51

Id. at 649.

52

Id. at 648.

53

See id. at 652 (noting that after 2014 every single top rm used the revised contract clause).

54

Id.

55

The market for derivatives is an example of parties devising a mechanism that functions to

update contract terms in light of chang ed conditions. The International Swaps and Derivatives

Association (ISDA) frequently updates the ISDA Master Contract. The ISDA Determination

Committees are a central authority to make ocial, binding determinations regarding the existence

of “credit events“ and “succession events” (such as mergers), which may trigger obligations under

a credit default swap contract. For discussion of the history of the formation of the derivatives

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 189 5

sovereign and corporate bond markets appear to lack a systematic means of

inducing necessary changes in contract language.

In the following Parts, we test the hypothesis that parties in the smaller

M&A deal market can function as mutual cooperators in a network that

facilitates revisions in standardized contract terms. As the basis for this

inquiry we rst turn in Part II to a salient development in contemporary

contract law: the willingness of De laware courts to depart from older common

law doctrine by permitting contracting parties to contract over fraud and

thereby limit their exposure to fraud claims.

II. C

ONTRACTING OVER FRAUD: I NCORPO RATING NEW L AW INTO

STANDARD TERMS

In this Part, we frame a test of how and to what extent the M&A market

is able to coordinate on contract revisions that respond to legal change. We

focus particularly on the responses by private M&A deal drafters to the

evolving changes in the ability of parties to contract over fraud.

A. From No-Reliance Clauses to the Fraud Carve-Out

At common law, eorts by commercial parties to contract over fraud were

strictly policed. Courts routinely held that claims of fraud were an exception

to the parol evidence rule even where the contract contained a merger clause

that most common law courts held was conclusive evidence that the written

agreement was fully integrated and contained all the terms of the parties’

agreement.

56

The rst crack on this bulwark occurred in New York in Danann

Realty v. Harris in 1959.

57

The contract in Danann Realty contained the

following language:

The Seller has not made and does not make any representations as to the

physical condition, rents, leases, expenses, operation or any other matter or

thing aecting or related to the aforesaid premises, except as herein

specically set forth, and the Purchaser hereby expressly acknowledges that . . .

network, see Jerey B. Golden, Setting Standards in the Evolution of Swap Documentation, 13 INT’L

FIN. L. REV. 18, 18-19(1994); M. Konrad Borowicz, Contracts as Regulation: The ISDA Master

Agreement, 16 CAP. MKTS. L.J. 72, 73-75 (2021).

56

See generally Stephen F. Ross & Daniel Trannen, The Modern Parol Evidence Rule and Its

Implications for New Textualist Statutory Interpretation, 87 G

EO. L.J. 195 (1995) (discussing the history

of the parol evidence rule).

57

Danann Realty Corp. v. Harris, 157 N.E.2d 597, 598 (N.Y. 1959) (emphasis added) (denying

a claim that the plainti was induced to enter into the contract based on false oral statements).

1896 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

neither party [is] relying upon any statement or representation, not embodied in

this contract, made by the other.

58

The New York Court of Appeals held that this clause, now known as a

“No-Reliance” provision, was enforceable to prevent the lessor from claiming

fraudulent misrepresentations regarding the expenses for maintaining the

leased property made by agents of the seller. The New York court emphasized

that the clause was clear and specically disclaimed any reliance on the

representations at issue in the case.

59

In the years following Danann Realty,

courts in New York consistently armed the ability of contracting parties to

deploy the No-Reliance clause to bar claims of fraud for extra-contractual

representations by agents of the seller.

60

Over time, the ability of parties to contract over fraud was recognized in

other jurisdictions as well. Thus, in 2003, the Delaware Chancery Court in

H-M Wexford LLC v. Encorp, Inc. armed the enforceability of an explicit

and clear No-Reliance cl ause to exclude evidence of extra contractual

misrepresentations.

61

The question of how far parties to agreements governed by Delaware law

could contract over fraud became more salient when buyers in private equity

acquisition agreements began in the early 2000s to insist on a “fraud carve-

out.”

62

The fraud carve- out originated in response to private equity deals’

growing use of indemnication provisions, which limit an acquirer’s remedies

(generally to ten to twenty percent of the contract price), in the event a seller

breaches certain representations regarding the qualities of the target

company. While buyers came to accept those seller-friendly indemnication

terms, they in turn negotiated for fraud carve-outs as exceptions that retained

58

Id.

59

Id. at 600.

60

ROBERT E. SCOTT & JODY S. KRAUS, CONTRACT LAW AND THEORY 433-35 (5th ed.

2013).

61

832 A.2d. 129, 142-43 (Del. Ch. 2003).

62

One seasoned partner explained that the emergence of the fraud carve out could be traced

to the rise of indemnication provisions in private equity deals:

“

People started to say a buyer shouldn’t have all the remedies available at common law in the event of

a breach, and so the indemnication regime began to emerge. Indemnication was supposed to be the

sole remedy . . . . At some point, buyers said, ‘I’m ne with limiting my ability to recover for a breach

of the seller’s reps to a 10 percent limitation of the purchase price, but if you literally lie to me, and I

rely on that to my detriment, then that shouldn’t be subject to the cap.’ Sellers would say, ‘Sure I can

agree to that, because the law doesn’t allow me to limit my liability for fraud.’ That’s the start of the

fraud carve out.

”

Zoom Interview with Anonymous Source Thirteen (Dec. 4, 2022).

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1897

a broader range of remedies for a buyer in the event the seller was found to

have committed fraud in the transaction.

63

From this perspective, the fraud carve-out was one side of a swinging

pendulum. Seller s’ desire for nality and a clean break upon the sale of a

company led to increasing use of indemnication provisions, which

circumscribed buyers’ remedies to a certain percentage of the purchase price,

among other limitations.

64

The fraud carve-out was the buyers’ reaction: they

were willing to swallow the limitations the indemnication regime imposed

on their potential recovery, but not when the seller had defrauded them.

65

The fraud carve-out has now been used in acquisition agreements for at

least two decades. These carve-outs can appear in multiple places in a private

equity acquisition contract, most commonly in the indemnication and

damages-cap provisions.

66

They have a simple structure. Whatever the

primary clause provides, typically a limitation on the type or quantity of

damages, the fraud carve-out species that the limitation does not apply if

the party in question (typically the seller) commits fraud.

67

But this led to

the question: what do the parties mean by fraud given its numerous and

varied meanings across jurisdictions?

68

If bound by the laws of a jurisdiction

with an expansive view of fraud, sellers could be subject to a much greater

liability than they had anticipated. Could sellers contract for a specic (and

limited) fraud liability at the outset? The Delaware courts, understanding this

concern in the private equity industry, said yes.

69

B. ABRY Partners: From the Fraud Carve-Out to Limited Fraud Clauses

The subsequent evolution of the fraud carve-out accelerated when the

Delaware Court of Chancery decided ABRY Partners v. F&W Acquisition in

2006. The issue posed was whether the parties could contract out of fraud

liability for statements made both within the contract (that is, as part of the

representations and warranties) and outside the contract (informal statements

about the company made by the sellers or their agents in the course of

negotiations or due diligence).

63

Id.

64

Id.

65

Id.

66

See Sarah McLean & Sarah Nealis, Fraud Carve-Out Provisions for M&A Agreements,

E

NERGY L. ADVISOR (Institute Energy L., Plano, Tex.), Oct. 2018 (“One of the most heavily

negotiated provisions of a private M&A transaction agreement is the indemnication

provision . . . commonly referred to as ‘fraud carve-outs.’”).

67

Id.

68

Glenn West, The Pesky Little Thing Called Fraud, 69 BUS. LAW. 1049, 1052 (2014).

69

See, e.g., H-M Wexford LLC v. Encorp Inc., 832 A.2d. 129, 140 (Del. Ch. 2003) (concluding

the parties can contract around fraud).

1898 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

Vice Chancellor Strine, while acknowledging the prior legal regime that

strongly disfavored parties contracting out of fraud liability, moved Delaware

law in a more “contractarian” direction.

70

He rst armed the general market

acceptance of No-Reliance clauses in the acquisitions world. The No-Reliance

clause, however, only applied to extra-contractual representations. Strine

then explained that, while parties still could not contract out of fraud liability

for representations and warranties in the contract, they could limit their fraud

liability for intra-contractual misrepresentations by specifying that the fraud

carve-out only applied to deliberate or intentional misrepresentations. Such

an exclusion would then be eective to eliminate claims based on reckless or

negligent misstatements.

71

As noted in Part II, our pr ior work compared the speed with which

obsolete No Recourse terms are revised in M&A transactions (private and

public) with public company bond issues.

72

Based on that earlier study, we

would expect the M&A market, and particularly its private equity subset, to

follow Strine’s invitation to precisely dene the fraud carve-out in order to

limit its eect to intentional fraud only. For the current project, the question

was not whether the market would respond by producing a “Limited Fraud”

clause, but rather (1) how quickly did it respond and (2) what was the

mechanism that propelled coordination among dierent parties to agree on a

Limited Fraud carve-out as a standardized term?

73

70

For Judge Strine’s own description of what ABRY did, see University of Virginia Law School,

Judge Leo Strine Jr. on Contracts Law,

YOUTUBE (Nov . 30, 2021),

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FEUHP9XmuLI [https://perma.cc/45KC-X4P 5].

71

Strine subsequently provided an account of how the fraud carve out emerged. He placed the

fraud carve out within a broader evolution of M&A deal architecture, which included no-reliance

provisions, variations in the common law of fraud by jurisdiction, and the emergence of

representations and warranties insurance for private target M&A deals:

“Originally it wasn’t really sure how reliable the no-reliance clause [in an acquisition agreement] was

. . . . It wasn’t really sure that you could even conne the statements on which people could sue. People

got more comfortable with that. [Second], fraud is also not a self-dening term in the common law

. . . . Over time there’s been much more expansion of the concept of misrepresentation to cover things

like negligent misrepresentation and so-called equitable fraud, which is essentially a statement by a

duciary. And so I think part of this fraud exception also came with the need to dene the state of

mind of the statement more precisely. And [nally] there’s also this emergence of an insurance product

here . . . essentially to ensure against the risk of misstatements, but I think primarily designed to cover

the indemnity bucket . . . . So I think what’s developed is to have a strong no reliance cause that you

can insist on if you’re a seller, an indemnity basket for non-scienter breaches of reps and warranties

that are found out, but with a fraud exception, with a scienter denition that allows for recovery if you

can prove, essentially, intentional misstatement that caused harm.” Id.

72

Revising Boilerplate, supra note 10, at 633 (examining the progression of these clauses by asking

whether it was caused by “exogenous shocks”).

73

But even if drafters were able to coordinate on a standard No-R eliance clause and a Limited

Fraud carve out, a further legal challenge emerged that motivated even more revisions to the basic

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1899

We turn now in Parts III and IV to examine both the speed and the several

pathways by which parties in the public and private variants of the M&A

network coordinated on standardizing the No-Reliance clause and the

Limited Fraud carve-out in order to eectively contract over fraud within the

space created by the recent changes in the contract law of De laware.

III. U

NPAC KING THE NETWORK

Commercial networks provide parties in multilateral markets with

cognitive resources and frameworks for addressing coordination problems.

74

Parties in these thick markets have limited information about the universe of

possible partners. It follows that it is worthwhile to search for potential

partners who know solutions a single party could not reach alone.

75

It is

therefore appropriate to conceive of the diverse contracting parties in the

private equity acquisition subset of the M&A market as members of a

network of collaborators. All of the participants in the market stand to be

harmed by the ineciencies of standardization, yet no single party can update

standard terms as conditions change or adjust to aberrant judicial

interpretations of ossied boilerplate. By participating in a network, the

parties in multilateral markets can collectively ameliorate these ineciencies.

To evaluate the nature and eect of the private equity network, we

interviewed thirty practitioners with experience in M&A deals. We rst note

the unique relationship this network has to the legal system in the M&A

context studied here. Unlike in other markets, where it is not unusual to nd

a disconnec t between highly specialized market participants and generalist

acquisition agreement. No-Reliance clauses and Limited Fraud clauses are not universally

enforceable. A number of states—particularly California and Massachusetts—decline to enforce

provisions that purport to eliminate fraud claims by contract. Glenn D. West & W. Benton Lewis,

Jr., Contracting to Avoid Extra-Contractual Liability—Can Your Contractual Deal Ever Really Be the

“Entire” Deal?, 100 B

US. LAW. 999, 1024-25 (2009). In several cases, buyers claimed that a governing

law clause designating Delaware law as the basis for evaluating claims under the contract did not

apply to claims for fraud that were grounded in tort rather than contract.

74

See Lisa Bernstein, Beyond Relational Contracts: Social Capital and Network Governance in

Procurement Contracts, 7 J.

LEGAL ANALYSIS 561, 563 (2016) (noting the power of “network

governance” to empower the enforcement of contractual duties).

75

Networks that form to obtain information about potential partners, including most famously

the biotech collaborations in Silicon Valley, have been studied by organizational sociologists. See,

e.g., Walter W. Powell, Kenneth Koput & Laurel Smith-Doerr, Inter-organizational Collaboration and

the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology, 41

ADMIN. SCI. Q. 116, 119 (1996) (“We

argue that when knowledge is broadly distributed and brings a competitive advantage, the locus of

innovation is found in a network of interorganizational relationship.”); Walter W. Powell, Inter-

Organizational Collaborati on in the Biotechnology Industry, 152 J.

INST. & THEORETICAL ECON. 197,

198 (1996)(analyzing the eects that institutional de signs can have on increasing cooperation).

1900 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

courts, the Delaware Court of Chancery is embedded within the M&A

ecosystem.

76

One respondent explained,

You have to understand. Unlike perhaps in other contexts, such as the federal

courts in New York, things are dierent in Delaware. The judges in the

Delaware courts are an integral part of the legal community. They listen to

the concerns of the lawyers, go to their conferences, and answer questions

about the direction of the law. Federal judges in New York do not do this. It

is rare that you will get a real shock in a Delaware case—these judges are all

experienced and careful lawyers. They think hard about what is best for the

market. Judge Strine, who wrote ABRY, prided himself in understanding the

bar and what was needed. I think that that’s true of the other judges too.

77

The Court of Chancery alone is not the sole coordinating institution in

the M&A market. As reported in the empirical analysis below, the ABRY

opinion, standing alone, was insucient to spark swift and comprehensive

adoption of fraud carve- outs and Limited Fraud denitions in private equity

acquisition agreements. Nor does the private bar operate wholly divorced

from the bench when periodic judic ial interventions make a mess of things.

Rather, the judiciary and advisory network work hand-in-glove, the former

seeking to anticipate the latter, and the latter translating the former’s

decisions into practice.

The Court of Chancery’s place in that ecosystem is visible due to its public

status, but the precise way that the advisory netw ork facilitates coordination

among market participants is less clear. Our prior work suggests several

dierent mechanisms that a lawyer network could possibly deploy to

coordinate needed changes in the standard acquisition contract.

78

One

possibility is the capacity of the leading law rms in the industry to serve as

the “spider in the web”—a governing structure or hierarchy that functions as

an agent of coordination.

79

Another coordinating factor could be the inuence

of a voluntary “spider” such a leading lawyer who uses their voice to inuence

change. A third avenue of coordination is the evolutionary process of

learning. This process proceeds from the individual level of deal partners

76

See William Savitt, The Genius of the Modern Chancery System, 2012 COLUM. BUS. L. REV.

570, 570-71 (2012) (arguing that the De laware Court of Chancery’s circumscribed jurisdiction and

deep connection to a specialized bar has allowed it to play a leading role in U.S. corporate

governance).

77

Zoom Interview with Anonymous Source Thirteen (Dec. 4, 2022).

78

Revising Boilerplate, supra note 10, at 633.

79

The evidence of the role of the ve leading law rms motivating coordination over changes

to the No Recourse clause in private equity suggests this possibility. See Revising Boilerplate, supra

note 10, at 651-53. The conception of the spider in the network web was introduced in Ariel Porat &

Robert E. Scott, Can Restitution Save Fragile Spiderless Networks?, 8 H

ARV. BUS. L. REV. 1 , 3 (2018)

(contending that a controlling relationship in the center of a network dictates its success).

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1901

teaching each other during bespoke negotiations to the group level of

collective engagement in conferences and bar meetings between drafters and

the judges who rule on litigated cases.

To aid in identifying the likely pathway(s) to coordination, we explained

to our experts that we were interested in understanding the evolution of

standardization of terms relevant to contracting over fraud. We asked (1) what

impediments might explain the time lag betw een bespoke eorts to contract

over fr aud and the standardization of those changes in the market contract,

and (2) what factors were most likely to aect the speed of a successful

coordination on new clauses.

80

We report below on the responses.

A. Leading Law Firms as a Spider

Our prior study of changes to the No Recourse clause found that

coordination in the market occurred among the ve leading law rms who

had the largest share of the private equity acquisitions market. This nding

suggests that perhaps these law rms assumed a special responsibility to

function as the spider in the network web. Thus, even if the pr ivate

acquisition market lacks an obvious controlling entity or hierarchy (such as

the way the ISDA Determination Committees function in the derivatives

market),

81

drafters in these leading law rms could nonetheless work together

to coordinate changes in response to new legal developments.

82

By acting as

rst movers, they could provide key information to others in the market

regarding the eciency benets of the new contract terms. Moreover, by

being the rst drafters in the market to design new terms, the design costs

for subsequent drafters would be measurably reduced. Our respondents,

however, rejected the prediction that we would see particular law rms as

leading the move to a new contractual standard. That was simply not how

contract innovation was likely to spread in this market. Instead, it was likely

spread through a more organic process, via industry conferences, meetings,

and other collective events.

83

80

Our interviews were generally done over Zoom and typically lasted between a half hour and

an hour. At the start of each conversation, we assured our respondents that nothing they said would

be attr ibuted to them and their identities would be kept condential. We then gave a short

explanation of why we had found the fraud carve out provision and the process of dening it

intriguing. In a handful of cases, we had follow-up conversations by email.

81

See Kahan & Klausner, supra note 10, at 727 (discussing the dierent sources from which

network benets can come).

82

For a similar nding on the eect of leading law rms in coordinating innovation regarding

sovereign bonds, see Stephen J. Choi & Mitu Gulati, Innovation in Boilerplate: An Empirical

Examination of Sovereign Bonds, 53 E

MORY L.J. 930, 948 (2004) (predicting that law rms

experienced with a “large volume” of sovereign bonds can lead the path towards newer terms in

bonds).

83

Zoom Interview with Anonymous Source Thirteen (Dec. 4, 2022).

1902 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. 171: 1881

B. The Inuence of the Voluntary Spider

In a pair of articles in the Business Lawyer, the rst in 2009 and the second

in 2014, Glenn West, a pr ivate equity specialist at Weil Gotshal, agged

undened fraud in fraud carve- outs as a persistent issue in pr ivate equity

deals. West’s basic exhortation (gentle in 2009, strident in 2014)

84

was clear.

Sell-side clients were willing to agree to fraud carve-outs from the various

damage cap provisions in their contracts because they understood fraud as

intentional misbehavior and they didn’t plan to engage in such behavior. But

the case law in many jurisdictions did not always match the clients’

understanding of fraudulent behavior. Instead, the term “fraud” was

susceptible to a range of meanings beyond intentional misstatements of the

particular private equity seller, including reckless and negligent

misstatement. Moreover, some cour ts showed a willingness to attribute the

misstatements of agents (managers of the company the private equity group

was trying to sell) to the sellers themselves. West proposed a solution: parties

could dene precisely what they meant by fraud in their contracts. In

contractarian jurisdictions, like Delaware and New York, courts would likely

defer to the agreement the parties had voluntarily made.

It is plausible to ask whether West’s two publications in the Business

Lawyer, the preeminent business law publication for U.S. practitioners, were

the key factors motivating the market to coordinate on standard terms for

contracting over fraud.

85

We did not explicitly bring up West’s articles in our

interviews. Instead, we asked what might cause the market to coordinate on

a standard market denition of fraud.

A number of our respondents agged West’s writings as important.

Multiple respondents even urged us to read them in order to better

understand the fraud carve- out issue.

86

That said, no respondent thought the

West articles on their own were capable of causing a move toward a

standardized clause. One respondent wryly observed:

I don’t know many senior lawyers who would actually sit down and read an

academic article. Most don’t even read the important Delaware cases. And

84

West & Lewis, supra note 72 at 1024-25; West, supra note 40.

85

There were also several Delaware cases touching on the fraud carve out issue in the 2013-

2017 period. See ENI Holdings LLC v. KBR Grp. Holdings, LLC, C.A. No . 8075-VCG, 2013 BL

332008, 2013 WL 6186326, at *39-41 (Del. Ch. Nov. 27, 2013) (discussing whether an agreement

carved out claims grounded in fraud from being subject to the contractual limitations period); JCM

Innovation Corp. v. FL Acquisition Holdings, Inc., C.A. No. N15C-10-255 EMD CCLD , 2016 BL

325304, 2016 WL 5793192, at *11 (Del. Super. Ct. Sept. 30, 2016) (“JCM counters that the exclusive

provision expressly carves out ‘claims arising from fraud.’”); EMSI Acquisition Inc. v. Contrarian

Funds LLC, C.A. No. 12648-VCS, at *11-12 (Del. Ch. May 3, 2017) (explaining that an agreement

appeared to carve out claims based on fraud from a section limiting remedies to indemnication).

86

We did not reveal that we knew West or were familiar with West’s work.

2023] Contract Production in M&A Markets 1903

make no mistake; Glenn [West] may be a senior partner at a big rm–but

those articles are academic. You need much more than just a couple of such

[academic] articles for change.

87

In other words, West’s academic writings alone were not the spider in the

network. For change, there needed to be more. Another respondent descr ibed

the dynamic as follows:

Glenn [West] had been telling us to dene fraud for years and we’d all nod

our heads and then just copy the old provisions from the prior deals. But at

some point, and probably after that [2014 Business Lawyer] article, the rhetoric

got ramped up. He and others at the ABA’s M&A meetings began telling us

that we were essentially committing malpractice by failing to dene fraud.

That got people to listen. There may have been something else going on as

well. There had always been the threat that opportunistic claims for fraud

would be made. It might have then happened in a few cases like EMSI.

88

C. The Inuence of Multilevel, Collective Engagement

The evidence suggests that the network lacks a single spider. In that

respect, the M&A world, and particularly its private equity subset, more

closely resembles the sovereign debt market than it does the trade association

networks such as those studied by Lisa Bernstein.

89

But unlike sovereign debt,

there is a practice of information exchange among the leading players in the

M&A/pr ivate equity market.

90

For example, in 2009 the M&A Committee

of the American Bar Association’s Business Law Section began sharing

information about the fraud carve-out issue with practitioners in two ways.

First, the M&A Committee’s Deal Points study,

91

which gives deal lawyers

insight into the current state of market practice, began reporting data on what

fraction of a sample of deals were limiting fraud to intentional actions in their

fraud carve-outs.

92

Practitioners could see in the study the initial uptake in

87

Zoom Interview with Anonymous Source Eighteen (Feb. 26, 2022).

88

Zoom Interview with Anonymous Source Twenty-ve (Feb. 18, 2022).

89